CHAPTER 4

The Value of Being Known

Helping Your Kids Feel SEEN

The old platitude about a relationship needing quality time is absolutely correct. Quantity time matters, of course. Our kids need us to be around, to play with them, to show up at their games and recitals. But helping our kids feel seen is about more than just being present physically. It’s also about connecting with them in this contingent way—using the triad of connection—and being there when they hurt, as well as celebrating with them when they achieve and succeed, or when they’re simply happy. It’s about showing up with our mental presence.

How good are you at seeing your kids? We mean really seeing them for who they are—perceiving, making sense, and responding to them in these contingent ways, ways that are timely and effective. This is essentially how your child comes to experience the emotional sensation not only of belonging, of feeling felt, but also of being known. Science suggests—and experience supports—that when we show up for our kids and give them the experience of being seen, they can learn how to see themselves with clarity and honesty. When we know our kids in a direct and truthful way, they learn to know themselves that way, too. Seeing our kids means we ourselves need to learn how to perceive, make sense, and respond from a place of presence, to be open to who they actually are and who they are becoming. Not who we’d like them to be, and not filtered through our own fears or desires. Just look at them, know them, embrace them, and support them as they grow into the fullness of themselves.

Take a moment right now and fast forward, in your mind, to a day in the future when your child, now an adult, looks back and talks about whether he felt seen by you. Maybe he’s talking to a spouse, or a friend, or a therapist. Someone they would be totally, brutally honest with. Can you imagine the scene in your mind’s eye? Perhaps he’s holding a cup of coffee, saying, “My mom, she wasn’t perfect, but I always knew she loved me just as I was.” Or, “My dad was always in my corner, even when I got in trouble.” Would he say something like that? Or would he end up talking about how his parents always wanted him to be something he wasn’t, or didn’t take the time to really understand him, or wanted him to act in ways that weren’t authentic in order to play a particular role in the family or come across a certain way?

We all know the cliché of the dad who wants his nonsporty son to be an athlete, or the mom who rides her child to make straight A’s, regardless of whether the child has the aptitude or inclination to do so. These are examples of parents who fail to see who their kids really are. When these are isolated experiences over the course of a childhood, they aren’t likely to make a huge difference—after all, no parent can be attuned 100 percent of the time. But when this pattern is repeated, these situations are likely to produce negative consequences for the child, the parent, and the relationship.

A different example occurred with a family we know. Jasmine is a single mom, and her daughter, Alisia, began complaining of unusual headaches when she was eight years old. She began missing school and other activities. After the pediatrician ran tests and proclaimed that there was nothing wrong with Alisia, Jasmine was at a loss. She wanted to support and believe her daughter—she began taking her to one specialist after another—but when she was repeatedly told that nothing appeared to be wrong, she couldn’t help but wonder whether Alisia was making up the pain to get out of doing things she didn’t want to do. Some days she let Alisia stay home, and some days she made her go to school or her other activities. The result was consistent conflict in the relationship.

The push-and-pull lasted over months, with Jasmine feeling guilty for not believing her daughter but also trying to make sure she didn’t miss out on school and important experiences, and Alisia trying her best to make her mom happy but suffering along the way. Eventually they visited a neuropsychologist, who discovered that Alisia did indeed suffer from a complex and puzzling disorder that manifested in just the type of symptoms she was experiencing. The good news was that the disorder was fairly easily treatable with medicine and a diet change. The bad news was that the young girl had suffered so long without relief; and just as bad, she could tell that her mother sometimes didn’t believe her when she conveyed what she was going through. Alisia had been living with both physical and emotional pain.

Jasmine, of course, felt awful about not being more supportive of her daughter. She had tried to remain sympathetic and understanding, and did the best she could with the information she had, but she hadn’t known how to make sense of the disconnect between what her daughter and the doctors were telling her. Even if her perceiving was open, her understanding was clouded, and thus her responding could only be ineffective. That triad of perceiving, making sense, and responding can form a three-link bridge connecting parents and children so that kids feel seen, but in Jasmine’s case the bridge wasn’t complete. Plus, she recognized that her own emotions were being triggered by the situation with Alisia; Jasmine’s mother had been sick often, and the last thing in the world Jasmine wanted to acknowledge was that her daughter might be dealing with some form of chronic illness. The feeling of helplessness in anyone can cloud the ability to create the triad of connection. Eventually, Jasmine got to the bottom of the problem, even though it didn’t all go just as she would have hoped.

This is an example of a parent who did her best to show up for her daughter and truly see what was going on with her child. None of us do this right all the time. Life is hard and complex, and having the intention to create clear and consistent connection is the best we can offer—repairing when it doesn’t go well, and maintaining the mindset to show up as best we can as life unfolds. Although Jasmine wasn’t able to immediately fix the problem, and even though Alisia didn’t feel supported throughout the entire process, by remaining vigilant Jasmine was ultimately able to discover the truth about Alisia’s pain. A less intentional parent might have simply accused her daughter of being manipulative and forced her to go to school. But Jasmine eventually came through for Alisia. She wasn’t perfect, but she showed up and saw her daughter, working to perceive, make sense, and respond however she could. In this case an actual diagnosis appeared. But even if Jasmine had determined that Alisia’s symptoms were contrived or psychosomatic, her role as a mother still would have been to show up for her daughter and perceive, make sense of, and respond to whatever was causing Alisia to tell her she was feeling that way. Regardless of the situation, the more fully we can see our kids, the more lovingly we can respond.

We offer this example to make the point that seeing your children doesn’t mean being a flawless parent. No one can read their kids’ cues perfectly all the time, and even if we try, we’ll still miss the mark sometimes. We might feel like we’re laughing with a child, only to have him perceive that we’re laughing at his expense. Or we might interpret something one of our kids says as evidence of anxiety and respond accordingly, only to have her offended because she feels like we viewed her as weak or unable to handle a situation. Or circumstances might keep us from actually knowing how to respond to what we see, as in the case of Alisia and her mother. The point is that truly seeing our children is often a hit-or-miss proposition, but making sincere efforts along each step of the triad of connection will give us the best chance for connection and understanding.

Mindsight

As she labored to address Alisia’s situation, Jasmine was demonstrating what we call “mindsight.” If you’ve read some of our other books you might recognize this term, coined by Dan, which describes a person’s ability to see inside his or her own mind, as well as the mind of another. A key aspect of mindsight is awareness, in the sense of paying close attention to what’s happening below the surface in a situation. This is what Jasmine worked hard to do with her daughter—to see what was going on with her little girl, while also endeavoring to remain aware of her own childhood experiences that were likely coloring her perspective. That’s what mindsight can offer: the ability to know your own mind, as well as the mind of another.

For example, imagine that you and your partner are arguing over a parenting issue. Maybe your partner wants the kids to do more chores, whereas you worry that the children are already too busy, so you don’t want to add more responsibilities. As your parental conversation progresses the conflict escalates, until you are both furious. At this moment, mindsight would be a powerful tool to call into practice. For one thing, it would create more self-awareness on your part, helping you pay attention not only to your own opinions and desires, but also to your frustration and anger. You might even notice that past issues—with your partner and maybe even with your own parents—are influencing the way you perceive the discussion. This kind of recognition has a good chance of significantly calming the discord.

What could help even more than directing mindsight inwardly for more self-understanding is to use it to consider what’s happening in the mind of your partner. Many of the various forces within you that have helped heighten the tension in the conversation are likely at work within your partner as well. By seeking to understand the fear or other emotions driving their reaction, and even feeling empathy for this person you care about, you can approach the argument—which can now become more of a discussion—much differently, coming at it more from a position of sensitivity and compassion, rather than defensiveness and judgment. You can still hold firm to your own position in the conversation, but your approach when communicating that position has a much greater potential to connect, rather than divide, the two of you. That’s the power of mindsight.

Yes, you may have guessed it: The triad of connection works not only for your relationship with your kids, but also for those with your other family members, life partners, and friends. Perceiving, making sense, and responding are a fundamental way we establish caring connections in life.

You can see, then, how powerful mindsight can be in a parent-child relationship. Parents who genuinely work on their mindsight skills generally have children who become securely attached. Suppose your four-year-old becomes apoplectic because you drained the bathtub after he got out and he, for some reason known only to him, wanted the tub to stay full. You might be tempted to argue with him, taking on a logic-based, left-brain-dominant approach and explaining the various reasons we always drain the water after a bath. But as you know, logic and rational discussions aren’t usually effective with a distraught preschooler. Your brain’s way of approaching the situation as an adult in this moment might be diametrically opposed to his own. Perhaps your son’s fantasy life was full of ships and sailors ready to set out on an overnight sea voyage while he would be sleeping, dreaming of the voyage unfolding in his bath, if only the bathwater seas had remained in the tub, not spiraled down that drain—you killed the sailors!

What if, instead of approaching only with your own goals and thoughts, you relied on your mindsight to imagine what might be going on inside of him? You might think about the fact that your little guy has had an exhausting day, with a soccer game followed by a play date. You might tune in to the story he was telling in the bath of sailors and journeys about to unfold. Then you might just hold him instead of lecturing. You might even ask him why it was so important for the water to stay in the bath. And you might acknowledge his feelings: “You wanted the water to stay in this time? You’re upset because you didn’t want me to drain it. Is that right?” By connecting first in this way, you’ll give yourself a much greater chance of helping him calm down and get ready for bed.

Likewise, if your twelve-year-old is in tears because she can’t find the shorts she wants to wear to her friend’s party, that may not be the best time to reprimand her for not planning ahead or offer a sermon about organization or not putting her things away. You can address family expectations about laundry and room maintenance later, when she can really listen. At that moment, the best thing you can do is to use your mindsight to notice what she’s feeling and recognize that, even though you might think her reaction is overblown, her emotions are very real to her. Then, whether you can help find the missing shorts or not, you can at least be aware of your daughter’s state of mind at the moment, meaning you can show up for her and help her deal with the disconcerting situation, even if you can’t fix the problem itself. Again, showing up for your kids isn’t about sheltering them from every problem—you don’t need to run to Target to replace the shorts. Showing up is about being there with your children as they learn to manage whatever obstacles they face.

Notice that we’re not describing some kind of superparent here. You don’t have to be able to read minds or transcend all your shortcomings or achieve some sort of spiritual enlightenment. You just have to show up. Show up with presence, and with the intention to let your kids feel that you get them and that you’ll be there for them, no matter what. That’s what it means to see—really see—your child.

And remember: It’s important to see your own mind as well. That means recognizing how you’re feeling at the moment and where your various emotions might be coming from. After all, some of what you experience in the middle of conflict or tension might have nothing to do with your son’s bath time, or what your daughter will wear to the party. If you can pay attention to what’s happening in your own mind, and with your own emotions, you’ll have a much better chance of handling yourself in a way that feels good to both you and your kids. Then, when you’re actually choosing how you respond in a challenging situation, rather than just reacting from your unconscious desires and inclinations, you can really see your kids and respond in a way that provides just what they need in that moment.

What’s more, when you respond with mindsight, you’ll be teaching your kids how loving relationships work. Attuning, helping a person feel felt, is the basis of a healthy relationship. When we do it for our kids, we’re another step closer to developing a secure base. And not only that—our kids will learn how to find friends and partners who will show up for them, as well as how to do the same for others. This means they’ll build skills for healthy relationships, including with their own kids, who can then pass the lesson on down the line through future generations.

What Happens When a Child Does Not Feel Seen?

Here’s a heartbreaking reality: Some kids live most of their childhood not being seen. Never feeling understood. Imagine how these children feel. When they think about their teachers, their peers, even their parents, one thought runs through their minds: “They don’t get me at all.”

What keeps a child from feeling seen and understood? Sometimes, it’s because we see the child through a “lens” that has more to do with our own desires, fears, and issues than with our child’s individual personality, passions, and behavior. That fixed filter can make it difficult for us to perceive, make sense of, and then respond in an attuned manner. Maybe we become fixated on a label and say, “He’s the baby,” or “She’s the athletic (or shy or artistic) one.” Or “He’s just like me, a pleaser,” or “She’s stubborn, just like her dad.” When we define our kids like this, using labels or comparisons—or sometimes even diagnoses—to capture and categorize them, we prevent ourselves from really seeing them in the totality of who they are. Yes, we are human and our brains organize the incoming streams of energy flow as concepts and categories. It’s just what our brains do. But part of our challenge is to identify such categories and liberate our own minds from their often constraining impact on how we see our child.

For example, “lazy” is a word we hear lots of parents use about their kids. Sometimes it’s because a child won’t study enough, or practice enough, or willingly help around the house. These parents likely think of “laziness” as a character flaw. But the reality is that when our children exert less effort than we expect or desire, there may be good reasons we haven’t thought of that they aren’t responding to a situation the way we’d like. Your daughter might be struggling with memorizing the state capitals not because she’s lazy, but because she has a learning challenge that needs to be addressed (in fact, challenged kids are often the ones giving more effort than most of their peers, but they’re not getting good results and the parents think they need to try harder). Or maybe she hasn’t yet learned how to study effectively, or she’s not getting enough sleep to sustain the energy needed to be alert and to learn well.

Or your son might not be eager to practice his free throw shooting every day because it’s not developmentally typical for a ten-year-old to make that kind of commitment to a sport. The point is not that your son shouldn’t practice if he wants to get better at basketball. Nor is it that your daughter doesn’t need to prepare for her geography quiz. We’re simply saying that as parents we should avoid making a snap judgment and slapping a label like “lazy” on our kids, rather than pausing to consider what might be going on beneath the surface. Labels can block us from seeing our children clearly. Even worse, our kids pick up on our use of these categories and classifications, then fashion their own self-beliefs around how they think we see them. All of us learn about ourselves through the mirror of the categories others place us in.

A related trap even well-meaning parents can fall into is wanting kids to be something other than who they really are. We might want our child to be studious or athletic or artistic or neat or achievement-oriented or something else. But what if he just doesn’t care about kicking a ball into a net? Or is unable to do so? What if she has no interest in playing the flute? What if it doesn’t seem important to get straight A’s, or it feels inauthentic to conform to gender norms?

Each child is an individual. When we let our own desires and categories color our perceptions, then we fail to see them clearly. And if we can’t see our kids, then what do we really mean when we say we love them? How can we embrace them for who they really are?

Sometimes the problem is as simple as a lack of fit between parent and child personalities. You might like to move like a hummingbird, accomplishing all tasks in a brisk and efficient manner. Then your daughter comes along with a built-in, inborn pace that’s more sloth-speed. Perhaps she’s easily distracted. Maybe she’s just curious, wanting to explore and learn from the fascinating details that surround her. What’s your job there? Is it to mold her into a smaller version of yourself, since efficiency is clearly superior to dilly-dallying? Obviously not. Rather, you might need to make some adjustments to the way you typically handle tasks. Maybe you wake her earlier since she takes longer to get ready for school. Or when you read with her before bed, you might need to allow time for questions and distractions. These are fairly simple modifications, but if you aren’t truly seeing her and how she functions in the world, then you won’t know her well enough to see how best to alter the routine to make life easier for both of you.

One of the worst ways we can fail to see our children is to ignore their feelings. With a toddler that might mean telling him, as he cries after a fall, “Don’t cry. You’re not hurt.” Or an older child might feel genuinely anxious about something that wouldn’t bother you at all, like attending the first meeting of a dance class. It’s unlikely that she will feel more at ease if you tell her, “Don’t worry about it—there’s no reason to be nervous.” Yes, we want to reassure our kids, and to be there for them to let them know they’ll be okay. But that’s far different from denying what they’re feeling, and explicitly telling them not to trust their emotions.

So instead, we want to simply see them. Notice what they’re experiencing, then be there for them and with them. The words might even be similar. We might end up saying something like, “You’re going to be okay,” or “Lots of people feel nervous on the first day. I’ll be there until you feel comfortable.” But if we begin by seeing them and paying attention to what they’re feeling, our response will be much more compassionate. Then, when they feel felt, it can create a sense of belonging as your child feels authentically known by you. She will also derive a sense of being both a “me” who is seen and respected, and part of a “we”—something that’s bigger than her solo self but that doesn’t require a compromise or the loss of her sense of being a unique individual. This is how seeing your child sets the foundation for such future integration in relationships where they can be an individual who is also a part of a connection.

What’s more, that empathy we communicate will be much more likely to create calm within our child. As is so often the case, when we show love and support, it makes life better not only for our child but for us as parents as well.

Welcoming the Fullness of Who Our Kids Are

In previous chapters we’ve talked about what creates secure attachment. Truly seeing our kids helps establish security since it lets them feel that someone embraces them for who they are—both the good and the bad. We want to communicate to our kids that we welcome them, that we adore them, that we want to know all parts of them, even when those parts aren’t always attractive or pleasant or logical. And how do we give our kids that message? In our responses to how they feel or act. Every parent-child interaction sends a message. We give our kids cues as to how we feel about that interaction. And you’d better believe they can read those cues like a card shark reading the room. They know what we’re feeling, whether we explicitly state it or not. And the extent to which they feel emotionally secure comes from how well their own inner experiences match with what they pick up from us, as well as how well they learn to make sense of those experiences with our help.

You’ve experienced this over and over again, even from the time your children were infants. When your baby saw a new person enter the room, or tripped and fell, he immediately looked to you for a signal as to how to respond. He wanted to know, Should I be afraid right now? Am I safe? And based on how you reacted, he learned how to gauge his own reaction—both in his behavior and in how his emotions were shaped and expressed. This interaction is called “social referencing,” and it represents the very beginning of your child’s development into an emotionally aware human. He’s seeing you.

As he got older, he continued to study you, and he got better and better at reading cues to discover how you felt in a given situation—cues you gave on purpose as explicit communication, or implicit messages embedded in your demeanor that you may not even have known you were sending. And these repeated patterns in communication significantly influenced his own mental model of how to feel about himself and the world around him.

We have friends whose son, Jamie, when he was a year old and climbing or doing something challenging, would audibly, and adorably, tell himself, “Careful, Jamie. Careful.” He had internalized and then would mimic the way his parents signaled to him to be more cautious when trying something risky. The cues we give our kids, typically from our own internal signals, can impact them negatively or positively. What we communicate can inhibit our kids from exploring in developmentally healthy ways, fueling fear and inappropriate anxiety, or it can stoke courage and the resilience that helps them feel comfortable launching beyond the familiar. (As always, keep inborn temperament in mind. Some kids need to be reminded to be careful, while others need time and encouragement before venturing into unknown realms.)

The point is that our kids learn to interpret fairly precisely how we feel not only about how safe the world at large is, but also how we feel when they communicate their emotions. They might get the repeated message that we truly see them and want to know how they feel—including when their feelings are negative or even scary—and that we will show up emotionally, regardless of how they feel. Or, maybe we communicate just the opposite.

Think for a minute right now about a time your child came to you upset about something. Did you use your mindsight to really see him and offer a contingent response? Which of these responses did you offer, either explicitly or implicitly?

A huge part of building secure attachment is seeing your kids and welcoming the fullness of who they are. It’s about making them feel free to share their feelings, even the big and scary ones that threaten to overwhelm them. Remember, they will internalize the messages you send, so if you tell them or give them the feeling that you “don’t want to hear it,” that will become part of what they know about their relationship with you. This is particularly true when they’re struggling, when the stakes are high, or when, as teenagers, they become more private—then you may not hear about things that would be important for them to come to you with. But it’s not too late to start communicating to your children that you are there for them. And you can apologize when you fail to do so, then keep sending cues that say how much you love them, regardless of how they act or what they say to you.

Seen versus Shamed

You may have noticed that helping kids feel seen overlaps in certain ways with the experience of safety, the first of our Four S’s. We want our kids to feel safe enough to show us who they are, to share with us what they’re feeling and experiencing without worrying that we’ll react in ways that evoke humiliation and shame, or fear and terror. Then we can see them that much more fully. But they can’t show us who they are if they don’t feel safe doing so.

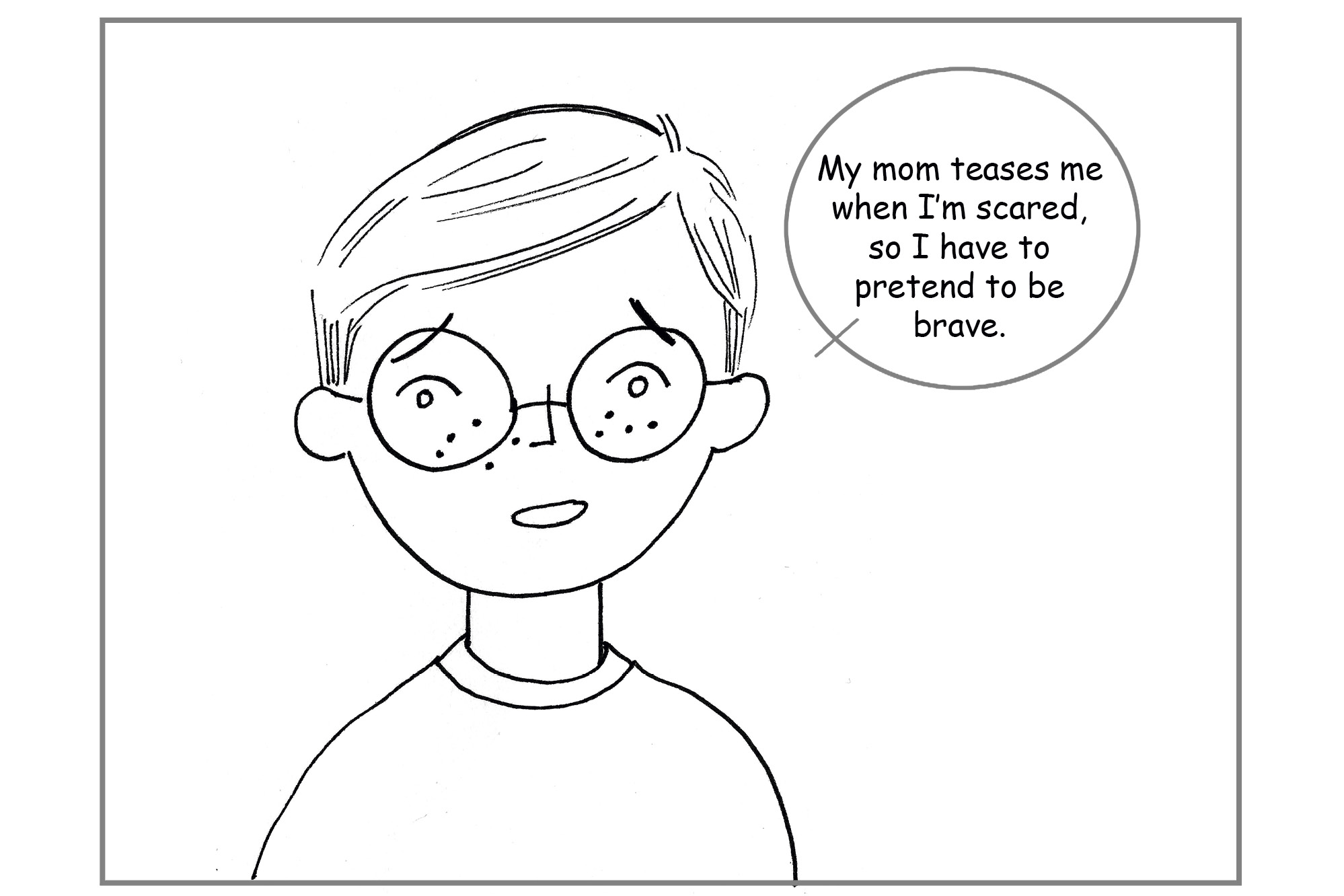

For example, if a mother shames her son for being afraid—of being alone, of Halloween costumes, or anything else—then he’s not going to let her know when he’s feeling anxious. It will therefore be that much more difficult for her to really see him.

As a result, he’s left to handle the feelings by himself. From there the problem snowballs. When he gets nervous about going on his first sleepover, he’ll be reluctant to tell his mother about his actual feelings. He will be left to face the situation alone, which often leads to more anxiety. So let’s say he refuses to go. Maybe he pretends to be sick, or maybe he simply throws a fit and insists he won’t go. His mom then sees his actions as oppositional and punishes him, but she never actually sees what’s going on within him. If instead she had used her mindsight to simply look and understand, she could have welcomed him to communicate his fear and anxiety. Then he could have shared what he was feeling, and maybe she could even have helped him deal with his nervousness in a way that allowed him to attend the sleepover.

When we dismiss or minimize or blame or shame our kids because of their emotions, we prevent them from showing us who they are.

Shame powerfully impedes the act of seeing. But we do it so often with our children. Instead of seeing and connecting with them, then problem-solving and supporting them so they can effectively handle their feelings, we play the shame card. Shame can be direct and involve statements that are dismissive and, if coupled with anger, even humiliating for a child. Shame can also be indirect. This can happen when a child is in an emotionally intense state and we do not attune in that emotional moment even though he or she is making an effort to connect. Repeated disconnection can happen at moments of either a positive state (like excitement about something) or a negative state (such as sadness, anger, or fear) that is not attuned to by the parent and can indirectly create a shame state in the child, or in anyone! Here, at moments of needing connection, none arises. For the developing child who is repeatedly not seen, made sense of, and responded to in an open and effective manner—the triad of connection is not offered at a time of need—these repeated experiences can create a state of shame that comes along with an internal sense that the self is defective. Why? It is, ironically, “safer” to believe that the reason your needs are not being met is because there is something wrong with you, rather than that your parents—whom you depend on for your very survival—are actually not dependable. This is how shame differs from guilt in which there is a sense that a behavior was wrong and can be corrected in the future.

With direct or indirect forms of shaming, we may make our kids feel like they are damaged, that something is wrong with them, even though they are simply being themselves and expressing healthy needs for connection. Sadly, such shame states can remain with us long past our childhood and shape how we function as adults, even if we are not aware that shame is a part of how our lives are being organized.

You can see the difference in the illustrations on the following page. Whereas seeing helps kids calm down and invites them to open up to us, shaming discourages them from showing us their true selves. And, worse, the shame typically doesn’t even produce the behavior we’re looking for. Or, if it does, the child behaves as we want on the outside but does so flooded with fear and dejection on the inside. In fact, research shows that a frequent experience of shame during childhood correlates with a significantly higher likelihood of anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.

Of course there are times when we need to challenge our kids to do more than they realize they can do. We don’t want them to miss out on the fun of a water slide simply because they’re nervous, or to skip a whole soccer season because they feel anxious about going to the first practice. That’s not what it means to see and support them. Likewise, we want to be realistic. Seeing a child means being aware of both strengths and weaknesses. So when you observe skills your child needs to work on—whether it’s patience, manners, impulse control, empathy, or something else—the loving thing to do is to give them practice in those areas. You don’t do them any favors by ignoring who they are, including any shortcomings or obstacles they may face.

But encouraging our kids to step outside their comfort zone, or working with them on social or emotional skills they’re lacking, is very different from shaming them when they don’t act the way we want. Again, this isn’t about coddling them or never asking them to try something new or go beyond what feels comfortable. The point is to allow them to show us what they’re really feeling, so we can be present to their experience and help them deal with the big emotions threatening to take them over. It’s about seeing them for who they really are.

What You Can Do: Strategies That Help Your Kids Feel Seen

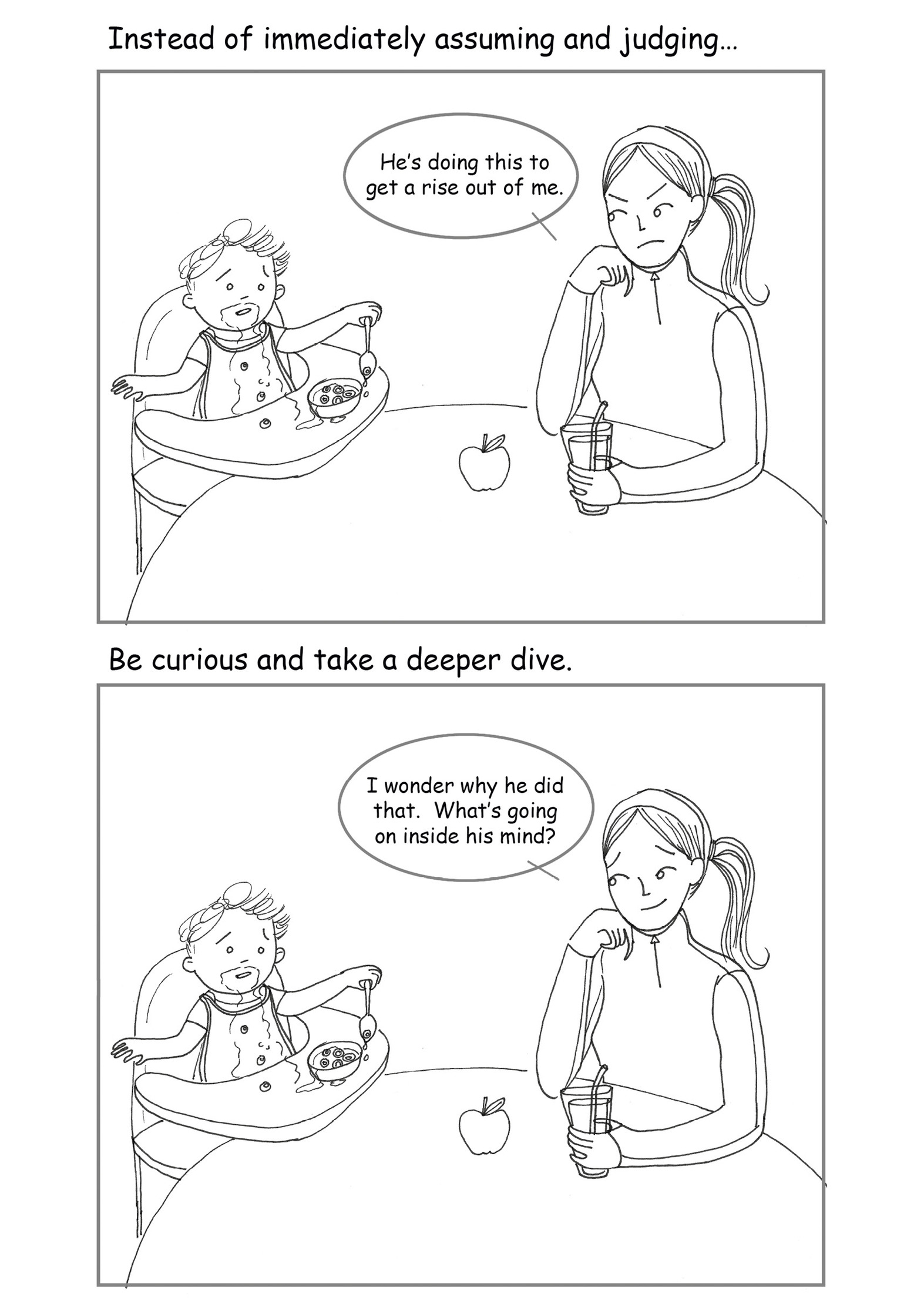

Strategy #1 for Helping Your Kids Feel Seen: Let Your Curiosity Lead You to Take a Deeper Dive

A practical first step to helping our kids feel seen is simply to observe them—just take the time to look at their behavior, attempting to discard preconceived ideas, and consider what’s really going on instead of making snap judgments. We can learn a great deal about our kids simply by slowing down and observing them. Seeing openly is made more likely when we challenge categories of understanding.

But again, really seeing our children often requires more than just paying attention to what’s readily visible on the surface. Sometimes we have to take a deeper dive to see what’s taking place beneath the external world of their actions and behavior. We want to observe their activities and listen to what they tell us, for sure. But just as with adults, it’s often the case with children that there’s more going on beneath the surface than they let on. As parents, then, part of our responsibility is to dive deeper, below what seems obvious.

Practically speaking, that means being willing to look beyond your initial assumptions and interpretations about what’s going on with your kids. It means taking an attitude of curiosity rather than immediate judgment.

This curiosity is key. It’s one of the most important tools a caring parent can use. When your toddler plays the “let’s push the plate of spaghetti off the high chair” game, your initial response might be frustration. If you assume he’s trying to press your buttons or be oppositional in some way, you’ll respond accordingly. But if you look at his face and notice how fascinated he is by the red splatter on the floor and the wall, you might feel and respond differently. The cognitive scientists Alison Gopnik, Andrew Meltzoff, and Patricia Kuhl have written about “the scientist in the crib,” explaining that a large percentage of what babies and young children do is part of an instinctual drive to learn and explore. So if you’re aware of this drive, when the spaghetti splatters, you might be just as frustrated about having to clean it up. But if you can take a moment and give sway to your curiosity, you might pause and ask yourself, “I wonder why he did that?” Then if you see him as a young researcher who is gathering data as he explores this world that’s so new to him, you can at the very least respond to his actions with intentionality and patience, even as you clean up the remains of his experiment. (And yes, having gathered your own data regarding this phase your young son is in, you’ll know that you likely need to put a towel down the next time you serve pasta.)

In our book No-Drama Discipline we encourage parents to “chase the why” behind kids’ behavior. By curiously asking “Why is my child doing that?” rather than immediately labeling an action as “bad behavior,” we’re much more likely to be able to respond to the action for what it is. Sometimes it really may be a behavior that should be addressed—as we keep saying, children definitely need boundaries, and it’s our job to teach them what’s okay and what’s not. But other times a child’s action may come from a developmentally typical place, in which case it should be responded to as such. And regardless, even if the behavior does require discipline (defined as teaching and skill building), we’ll be much more effective disciplinarians (teachers) if we can curiously chase the why and determine exactly what’s going on in the child’s mind and where the behavior came from in the first place.

The same goes for other behaviors. If your child is quiet when she meets an adult and resists speaking up and saying hello, she may not be refusing to be well mannered. She may simply be feeling shy or anxious. Again, that doesn’t mean that you don’t teach her social skills along the way, or encourage her to learn to speak in situations that are uncomfortable. It just means you want to see her for where she is right now. What are the feelings behind the behavior? Chase the why and examine the cause of her reticence; then you can respond more intentionally and effectively.

By the way, we’re very much in favor of setting clear, and even high, expectations for kids. They need to learn the value of working hard, and to be encouraged to do more than they realize they’re capable of. However, there are also times when, if we dive deeper, we’ll discover that we’re making unrealistic demands on a child. As parents we definitely want to help our kids be all they can be; but we don’t want to ask them to do things that are truly out of reach.

An important question to ask is whether a child won’t behave, as opposed to whether he can’t. If he won’t behave as he’s asked, then our response may be very different from a situation where he can’t sit still or consistently follow directions, because of hyperactive tendencies or developmentally inappropriate expectations or some other reason.

Tina recently had an exchange that made this point well. She was speaking to educators about diving deep and chasing the why when it comes to understanding student behavior. During the Q&A at the end of the presentation, a caring and experienced teacher, Debra, stood and said, “If what you’re saying is true, then I have to completely rethink the way I handle discipline in my classroom.” Tina asked for details, and Debra explained that she used clothespins with the children’s names written on them and moved the clothespins into a “red-light, yellow-light, green-light” chart, where the clothespins were all clipped on the large felt traffic light. Each child began a new day in the green light section of the chart; then if they misbehaved, their clothespin would be moved into the yellow-light section, which was a warning. Subsequent infractions moved them into the red-light part of the chart, which meant that parents were notified of the bad behavior and there were specific consequences, such as losing recess.

The rest of the exchange between Tina and Debra went something like this:

How effectively is the system working?

Great, with most kids. But not with a couple of the boys in my class.

So the same couple of names are ending up in the red most of the time?

Yes. One boy’s pin has been moved so many times his name has rubbed off.

For the same types of behavior, over and over?

Definitely.

Well, just based on that, it sounds like the system isn’t really working as an effective behavior management tool. The consequences he’s facing from you and from his parents aren’t really changing his behavior. What about his classmates? How does his difficult behavior impact them?

His peers are annoyed with him, too. They get tired of him intruding on their space, talking to them when they’re working. They also hate all the interruptions where we have to stop our class activities to deal with his behavior.

So let me say back what I’m hearing. At a developmental moment when having your peers accept and like you is so strong, this boy continues these behaviors despite all the negative feedback he’s getting from classmates, and then more negative consequences from his parents, and you?

That’s what I’m saying. I need to rethink my system.

Right. Why, in other words, would he continue to do things that lead to such negative responses from virtually everyone around him? Surely that doesn’t feel very good to him. Kids typically don’t like getting in trouble over and over again and having peers dislike them repeatedly. Let me ask you something. Would you ever move a child’s clothespin into the yellow or red sections for not reading quickly enough if the child had dyslexia?

Of course not. He couldn’t help that.

Of course not. Because you’d know it’s not a choice that the child is making to purposely avoid doing what’s expected. I’m wondering if when we see a child who continues with the same nonproductive behaviors that cause so many problems for him, well, maybe it’s not a choice for him, either. Is it possible that it’s a can’t, but it’s being treated as a won’t? Maybe he doesn’t have the skills or development yet to handle himself differently. If he had a learning challenge, we’d typically see it from a more curious and generous lens and support him to thrive. So why would it be different if the challenges are social or emotional or developmental? And we’d never want to punish a child for something the child can’t help.

I’d hate it if someone got mad at me for something that wasn’t my fault, and especially if it kept happening in front of my friends, and if I was trying to do better but just couldn’t.

Exactly. And none of this means you let the boy flout classroom rules or continue as a distraction. The behavior, obviously, has to be addressed for his sake and for the learning of the others in the room. But this different lens gives you a better idea of why your current system isn’t working with this boy. And with more curiosity and a better understanding of where he is, you can address the behavior from not only a more empathetic perspective, but from one that helps you discipline more proactively and effectively as well. It may require some trial and error using alternative strategies and some creativity and patience to help this boy, but I’d encourage you to work with him, reflecting on his behaviors together and seeing what he thinks might help him be successful.

This conversation focused on a school situation, but it makes the “can’t versus won’t” point well. If your child can’t behave differently, how do you feel about punishing her for what she can’t control? Sometimes a can’t is rooted in an underlying obstacle, like a learning challenge or sensory processing disorder or pervasive developmental disorder or chronic sleep deprivation or adjusting to a divorce or a new house, or…This doesn’t mean the child can’t grow or build skills; it just means that right now the demand of the environment exceeds her current capacity. The behavior might be more about where the child is developmentally, and she simply needs more time and problem-solving skills to be more successful. But we can’t know whether that’s the case unless we dive deep and see what’s going on beneath the surface.

Strategy #2 for Helping Your Kids Feel Seen: Make Space and Time to Look and Learn

Notice that intentionality is key when it comes to really seeing and knowing our kids. The same goes for our second suggestion. Much about seeing our kids is simply paying attention throughout the day. That’s one of the great things about a whole-brain approach to parenting: You don’t have to wait for big, serious conversations to do the important work of teaching or learning about your kids. You just have to show up and pay attention—to be present.

That being said, though, while you’re paying attention throughout the day, you can also make a point to generate opportunities that allow your kids to show you who they are. Sure, you can learn all kinds of things simply by observing them while they live their lives, or by listening as they talk about what struck their attention as they went through their day. But you can also take steps to create space for conversations that will take you deeper into their world so you can learn more about them and see details you might not otherwise be privy to.

Nighttime can be a gold mine when it comes to going deeper with your kids. There’s something about the end of the day, when the home gets quiet and the body feels tired, when distractions drop away and defenses are down, that makes us more apt to share our thoughts and memories, our fears and desires. The same goes for kids. When they get still and settled, their questions, reflections, wonderings, and ideas can emerge, especially if you’re snuggled in close and not rushing them.

What’s required, though, is a bit of effort and planning in terms of the family schedule. Kids need an adequate amount of sleep—we can’t stress that enough—so ideally you’ll begin bedtime early enough to make time for your usual routine plus a few minutes of simple chat or even quiet waiting time to allow your children to talk if they are inclined. We’ve written elsewhere about the dangers of overscheduling children, and how bedtime rituals and ample sleep can be powerful tools for helping regulate their emotions and behavior. With a bit of forethought, you can schedule a few minutes of connecting time as part of your nighttime routine. When they’re not rushed, they might feel inclined to share details of the day and ask questions that help you gain a fuller understanding of what’s going on in your child’s actual and imaginary worlds.

We know what some of you are thinking: I don’t have one of those kids who naturally and willingly shares what they’re thinking and feeling. We get it. Plus, you don’t always know how to get conversations started. The answer to the “How was your day” question seems to inevitably lead to the dreaded answer, “Fine.” Aren’t you tired of asking that? They’re sick of hearing it, too! Imagining a chat time added to your child’s bedtime routine might produce the unpleasant image of you and your child silently lying next to each other, both of you waiting for something important to be shared.

We have a few responses to this concern. First of all, keep in mind that the idea is not that every evening you’ll hear some earth-shattering revelation, or that you two will engage in a deep and uber-meaningful exchange. That’s not realistic even between adults, much less with kids. What’s more, it’s not the goal. Sure, there may be times when more significant conversations take place, but remember that the ultimate aim for such moments is simply to be present to your children—to create space and time to get to know them better and to understand them at a deeper level, so you can help them grow into the fullness of who they are.

As for the “How was your day” issue, that question may be more than sufficient to elicit details from your particular child. With some kids, getting them to talk more at bedtime is the last thing a parent wants. In these situations, the parent’s job may not be to encourage conversation, but to steer it in more focused and profitable directions, so that the discussion can lead to greater connection and understanding. But if you’re one of the many parents with a child who doesn’t as eagerly share inner thoughts, then you may need to ask more specific questions. And the more you see and know your child, the easier that will become.

You can find plenty of ideas and even products online or in libraries to encourage more meaningful discussions with your kids. Some offer conversation starters; some give you interesting questions to ask, or ethical dilemmas to consider together. You can use the ideas you find to prime the pump of your parent-child dialogue. It’s not always easy, but paying close attention to your children and their world will help generate better questions, and you’re much more likely to get better answers than “fine.” Plus, keep in mind that truly seeing your kids is about being able to read where they are and notice that at times, they simply don’t want to talk. Silence is okay too. Being quiet together, simply breathing, can be intimate and connecting. So don’t feel pressure to force conversation when it’s not the right time.

We know it can be confusing, trying to determine what to say when, and whether to encourage conversation or let things be quiet. But that’s one more great thing that comes with really seeing your kids. When you take the time to fully know them, it becomes that much easier to know when to say what, and when to just let silence exist between you. Just a few minutes of space and time to allow anything to emerge from your child’s imagination or her day can be very rewarding—for both of you, and for the relationship.

Again, you’ll see plenty just by keeping your eyes open as you and your kids live your lives. But one of the best ways to see your kids—and to help them feel seen—is to create the space and time that cultivate opportunities for that kind of vision to take place.

Showing Up for Ourselves

One of our deepest needs as humans is connection—to be seen and therefore known. Being understood by another allows us to know ourselves and to live authentically out of our internal experience.

To what degree have you felt seen and known and understood in your own life? When we aren’t able to feel or express our internal experiences, or when no one is present in our internal landscape, we can easily feel alone, perhaps losing access to our own insight, reducing even our ability to know ourselves deeply.

If you grew up with a caregiver who modeled being aware of his or her inner life, and who paid attention to and honored your feelings and experiences (without becoming overbearing or intrusive), you likely know what it feels like to be seen and acknowledged, to feel felt and understood in your inner world. And chances are you can also do this fairly well in your own relationships. As a result, you enjoy a certain richness in the way you relate to others, including your children, knowing them in deeper ways. Even when things don’t go as you’d like, your relationships can serve as a source of strength and meaning.

Many people don’t have this advantage. They instead grew up in families where almost all of the attention was focused on external and surface-level experiences: what they did and how they behaved, misbehaved, or achieved. Families like these can have fun with one another and enjoy activities together, but the world within is largely ignored. Dinnertime discussions might cover surface topics like current events, what the dog did, what the neighbor said, or other topics that, while being perfectly acceptable subjects of conversation, are cut off from the internal experiences of feelings, memories, meanings, and thoughts—the subjective, rich, inner nature of the mind. Their friendships might be outwardly focused as well. We all tend to have at least some relationships where we discuss superficial topics, rarely sharing vulnerabilities, thoughts, feelings, desires, or fears, and that’s fine as long as we also have significant friendships where we’re truly known and deeply know the other.

The degree to which we live on the surface without a deeper understanding of ourselves, our significant others, our children, and our closest friends often correlates with how seen or unseen we felt by our attachment figures.

Remember from our earlier discussion of attachment approaches that in an avoidant attachment pattern, the importance of relationships and feelings is dismissed, ignored, or minimized. In fact, at one year babies can already demonstrate the adaptive strategies of avoidant attachment by externally ignoring their caregivers after a brief separation—acting as if they didn’t need them. Such a baby might feel afraid or sad but have already determined that his caregiver doesn’t respond very well when he expresses these feelings and needs. The baby then adaptively avoids turning to the caregiver to express himself and instead learns that he’s alone in his emotions.

Without therapy, reflection, or other relationships that give him a different experience of relationships, the child with an avoidant attachment to the primary caregiver will likely grow into an adult who focuses primarily on external matters as well. It’s an organized, completely adaptive response to his situation. If you have an emotion or need, and your caregiver ignores it or dismisses it as unimportant, turning their attention away from your need, then it makes perfect sense that you would begin to live more from a left-hemisphere-dominant approach to the world, dismissing your own emotions (and everyone else’s) as less than important. When you haven’t been seen, the circuitry that allows you to tune into other minds and acquire that type of insight doesn’t appear to develop as fully, and you can eventually stop seeing yourself.

You’ve certainly had people in your life, your parents or colleagues or partners or friends, who felt uncomfortable seeing and dealing with emotions—yours or their own. Those emotions are often expressed with the nonverbal signals of eye contact, facial expressions, tone of voice, postures, gestures, and the timing and intensity of responses. Those are all expressed and perceived predominantly by the right hemisphere of the brain. If that side of the brain didn’t have the nurturing, attuned connections that stimulate its growth, it may be relatively underdeveloped—just waiting for a book like this to invite it to get back into the growth and connecting mode! The brain’s ability to grow and develop is never lost.

Let’s explore a bit and reflect on your experience with your attachment figures and the degree to which you felt seen, known, understood, and responded to. Then we’ll let you consider your relationship with your own children. Ask yourself these questions, paying attention to any thoughts and emotions that arise. See yourself and your own responses, taking each question one by one, slowing down to give extra thought to any that spark a stronger reaction within you.

- To what degree did you feel truly seen by your parents, as we define it here (i.e., they perceived your internal landscape deeply, then offered a response that matched)?

- Do you currently have relationships in which you have more meaningful conversations, where you discuss matters having to do with your memories, fears, desires, and other facets of your inner life?

- What about with your kids? Do you interact with them in ways that introduce them to and honor their inner worlds? Do you model what it means to pay attention to your own mind and emotions?

- How often do they feel truly seen by you? Do they feel like you embrace them for who they truly are, even if it’s different from you or your desires for them?

- Do your kids ever feel shamed for having and expressing their emotions? Do they believe that you’ll show up and be there for them, even when they’re feeling distressed or behaving at their worst?

- What’s one step you could take right now, today, to do a better job of truly seeing your children and responding to what they need? It might have to do with chasing the “why” when something happens you don’t like, or creating space to go deeper. Or maybe you want to do a better job of taking an interest in something they care about.

Remember, nobody’s perfect, and every parent is going to miss opportunities to see their children. Plus, it’s impossible to fully see and completely understand anyone, including our kids. So you shouldn’t feel pressure to rise to some level of parental sainthood. Just take one small step toward making your kids feel more seen and understood than they already do. Enjoy the rewards that come with that step, and then take another. Each new step deepens and strengthens the connection, and prepares your children to do the same in their relationships, all the way through childhood and adolescence and into adulthood.