Five

OIL OPERATIONS AND THE

BATTLE OVER ANNEXATION

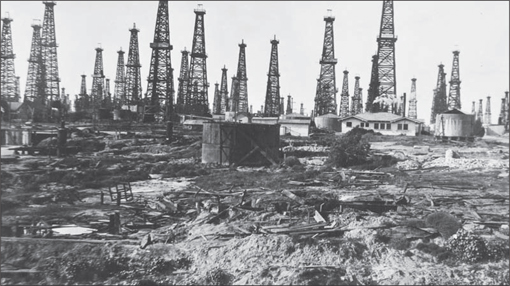

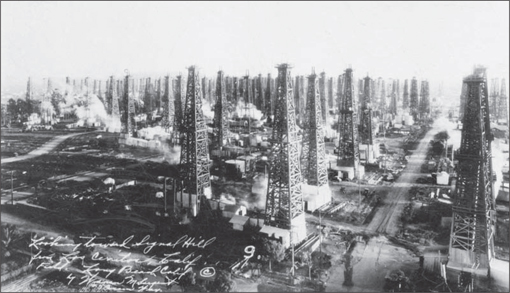

The discovery of oil in Signal Hill in June 1921 and the subsequent invasion of oil drilling operations into the Los Cerritos neighborhood became the critical factor in determining whether Los Cerritos would agree to annexation by Long Beach. Los Cerritos residents voted down annexation in 1922 by a vote of 187 to 110, which was a win for the oil companies. Phillip L. Bixby entered into a lease with the United Oil Company for drilling on 30 acres between Cota Avenue, the Pacific Electric right-of-way, Wardlow Road, and Bixby Road. Nearly every lot on Pine Avenue, Weston Place, Pacific Avenue, and Chestnut Avenue south of Bixby Road had an oil well on it. Between the fires and noise, many residents chose to abandon the neighborhood. Some took their houses with them, and a nightly “parade of houses” began. On January 14, 1926, a gas blowout occurred on the southwest corner of Bixby Road and Pacific Avenue. On February 23, E.E. Combs Well No. 5, at the northeast corner of Pacific Avenue and Bixby Road, caught fire, injuring many, including the fire chief, who collapsed from smoke inhalation. Children could not walk home from school unescorted because of the fires. The wells were initially productive. Getty No. 13, on Weston Place, drilled to 4,400 feet, brought in 700 barrels a day. Of the 42 drilling permits issued by the state in March 1926, 15 were for Los Cerritos. In 1927, the field declined and the oil flow collapsed. By then, the neighborhood was devastated.

The city sought initially to appease those favoring drilling to secure annexation, even proposing to allow each citizen to decide on drilling on their lots. Ultimately, the city was pressured into banning oil operations in residential neighborhoods, including Los Cerritos. Los Cerritos was annexed to Long Beach in 1924 after a contested election in December 1923 was upheld. The Los Cerritos Improvement Association, under the leadership of its first president, Charles R. Rowlett, worked to return the area to its former beauty. In 1951, a portion of Los Cerritos Park was renamed for Rowlett.

CAMPBELL HOME AND OIL WELL. Reginald Campbell, a plumber and father of Norma Campbell Craig, stands in his backyard at 3841 Pacific Avenue in 1926. The Campbells moved the house to 235 East Claiborne Place to escape oil drilling. (Courtesy of Hyra and David Goldberg.)

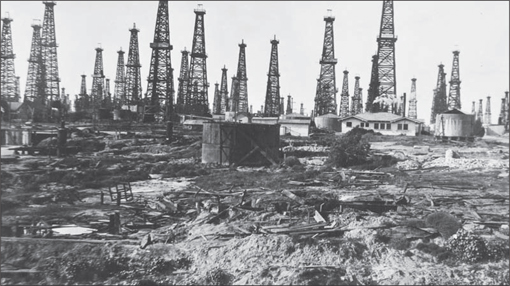

DERRICKS IN LOS CERRITOS. This mid-1920s photograph shows how oil wells were positioned very close to homes. (LBHS.)

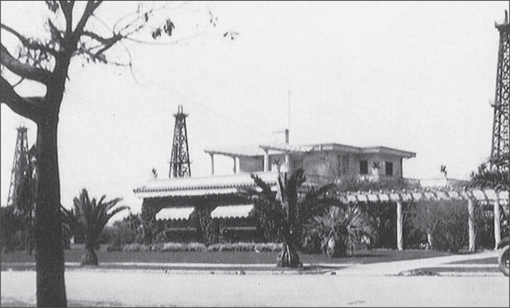

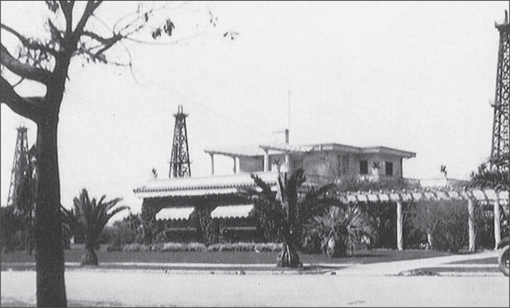

OUTSIDE YARD OF BIXBY MANSION DURING OIL DRILLING. Thomas Gilchrist, who purchased the Bixby mansion in the 1920s, was an Oklahoma oilman. Arriving in California at an opportune time, his house positioned him to experience the oil-drilling operations firsthand, but it remained vacant during peak drilling periods. At one point, even this home was thought to be threatened by oil operations. (Courtesy of Duane Rose.)

OIL WELLS IN LA LINDA. This photograph of 3800 Weston Place shows the oil derricks in La Linda after many residents who bought the lots decided in 1926 to delay home construction to drill for oil. (Courtesy of the Jablonski family.)

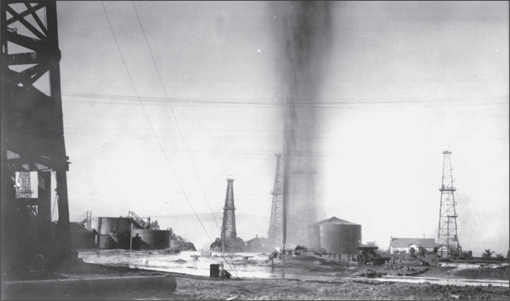

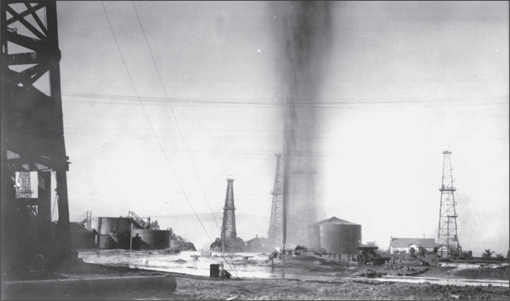

OIL WELL BLOWOUT. This blowout occurred on the southwest corner of Pacific Avenue at Bixby Road on January 14, 1926. The George Johnson No. 4 well blew, raining water and oil onto the neighborhood. Many residents recall being escorted by their parents back and forth to Los Cerritos School because of oil fires. (RLC.)

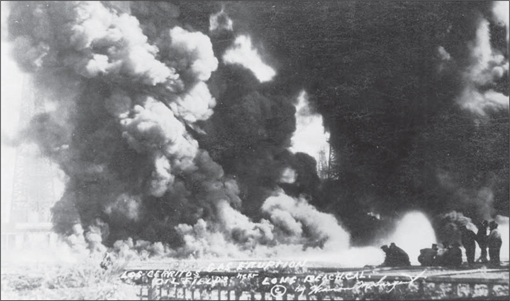

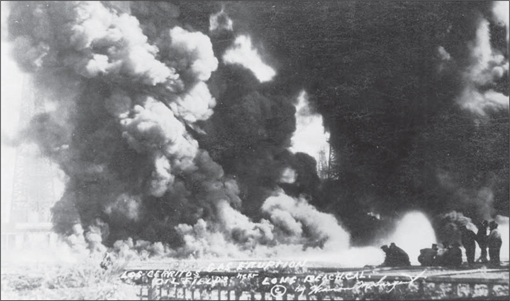

500 MEN FIGHT BLAZE. Gas burst through fissures in the ground at E.E. Combs Trust Well No. 5 at the northeast corner of Pacific Avenue and Bixby Road on February 24, 1926. The explosion caused the George Johnson No. 5 well to blow. The fire was visible for five miles. Fire chief William Minter collapsed from exhaustion and smoke inhalation, and six men were injured. Welch Stanberry’s house was significantly damaged. (Courtesy of CSU Dominguez Hills Archives.)

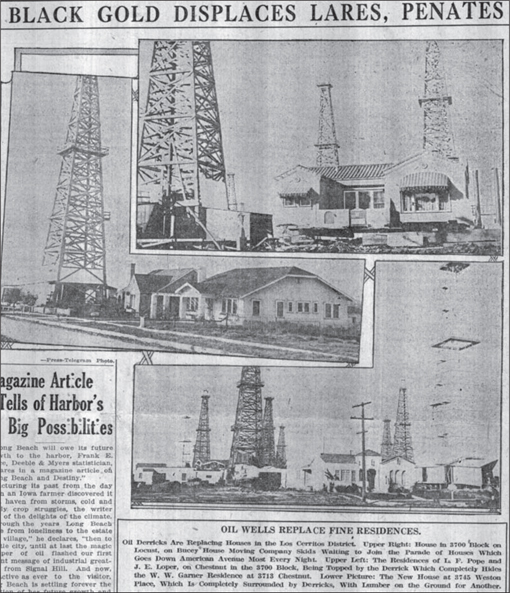

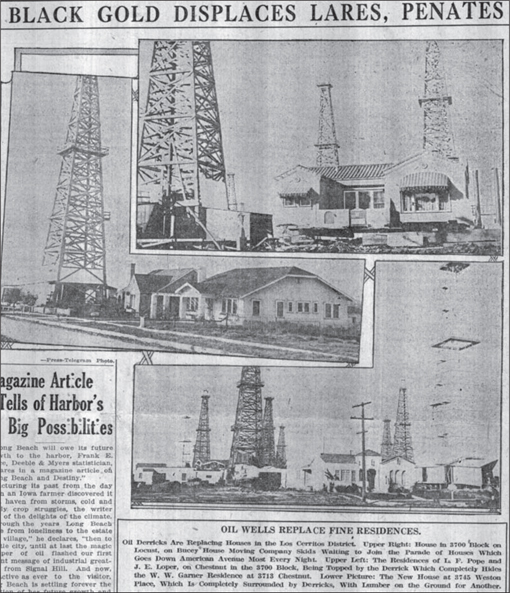

OIL WELLS REPLACE HOMES. This clipping from the December 27, 1925, Press Telegram notes a parade of houses moving down American Avenue (now Long Beach Boulevard) nearly every night as residents escape the oil-drilling operations. In the center photograph, rigs tower over the homes of L.F. Pope, J.E. Loper, and W.W. Gardiner. In the bottom photograph, the home at 3745 Weston Place is completely surrounded by drilling rigs.

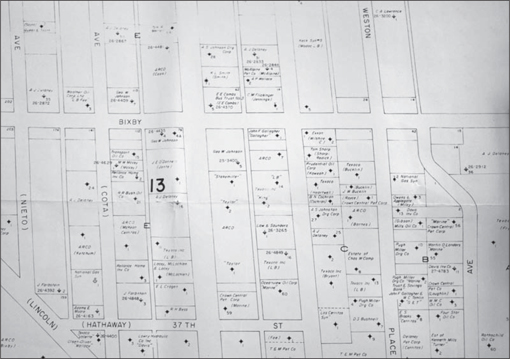

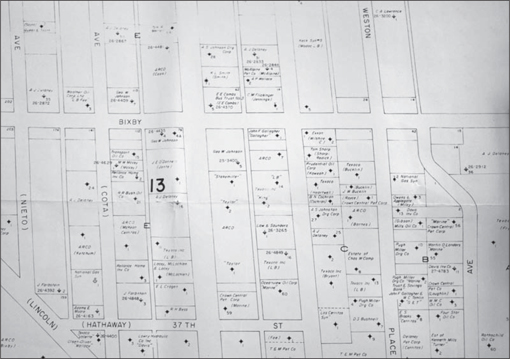

OIL WELLS IN LOS CERRITOS. State Division of Oil and Gas Map 137 indicates lots with oil wells. By the end of 1926, 236 wells had been drilled in Los Cerritos, with 158 producing oil. Only 25 percent of these would recoup their investment, and most would not last another year. The map identifies the individual oil wells and owners.

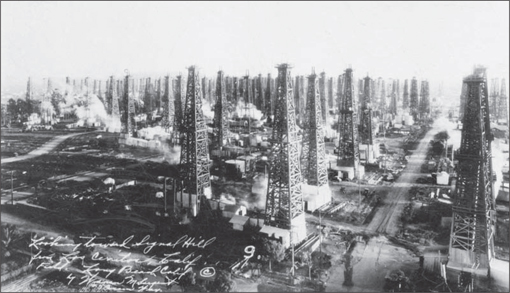

LABYRINTH OF DERRICKS. The Los Cerritos field was described by Long Beach Fire Department drillmaster Jones as a veritable labyrinth of derricks. At the time Jones took this photograph in late 1927, the field was gasping its last. One-third of the wells had been abandoned. (Courtesy of CSU Dominguez Hills Archives.)

OIL WELL ABANDONMENT PROCESS. Drillmaster Jones of the Long Beach Fire Department documented through photographs the abandonment of wells in Los Cerritos. Here, after the rotary mud has been removed from the sump, the excavation must be filled in and the surface of the lot graded before the property owner would accept a quit claim deed. (Courtesy of the CSU Dominguez Hills Archives.)

OIL WELL CASING REMOVAL. After the well has been abandoned to the satisfaction of the California State Mining Bureau, a certain percentage of the casing may be salvaged. The casing is dynamited loose at a proper level, and raised out of the hole by means of hydraulic jacks. (Courtesy of CSU Dominguez Hills Archives.)

VIEW FROM LOS CERRITOS. Even after drilling ceased in Los Cerritos, this was the view toward Signal Hill that greeted residents from the edge of their neighborhood.

3733 PACIFIC AVENUE. In this 1950s photograph of a home on Pacific Avenue, oil wells are still visible to the left of the house, indicating that drilling on the outskirts of the neighborhood continued. (Courtesy of Jon St. Jacques.)