Describe what you do for work. Describe what your company does.

Describe what you do for work. Describe what your company does.

Describe the movie The Matrix.

Describe the movie The Matrix.

If we gave you five million dollars, what would you do with it?

If we gave you five million dollars, what would you do with it?

What is your personal philosophy?

What is your personal philosophy?

What do you want most in a new hire or colleague?

What do you want most in a new hire or colleague?

Years ago, Chris was sitting in a very uncomfortable kid’s desk chair at a satellite location of a small New England college. A man with meticulously combed hair and a nice suit walked in, put his briefcase down, put his feet up on the desk, laced his hands behind his head, and went into a speech, the details of which Chris can remember almost entirely, verbatim, over a decade later.

Kenneth Hadge taught more solid and actionable ideas about business than Chris had ever learned before. Honestly, the only person who rivals Hadge in the usefulness of his ideas is Sir Richard Branson with his masterful book Business Stripped Bare. This instructor, underpaid and representing a very small college with a roomful of not-so-obvious future business leaders, had many great ideas. All of them were simple to remember, useful, and actionable. Here is why Chris remembers this so many years later. Here’s a Ken Hadge lesson.

“When someone comes into my office and starts telling me about paradigm-shifting, world-class whatever, I hold up one hand, wait for them to stop talking, and I say, ‘Tell it to me like I’m six years old.’”

This is the Ken Hadge method, forever named in this book in tribute. “Tell it to me like I’m six years old.”

In the quest for impact, one area that baffles people is thinking that big words equal being understood. Quite often, the opposite is true. If someone trips over your incredible vocabulary, they are not thinking about the idea you’ve put forth. Instead, they’re worried that they don’t know the word you used, and they’re worried you’ll think they’re stupid for not knowing it. Even if you yourself had to double-check the word in the dictionary before using it, it’s going to sit there like an obvious adornment on an otherwise simple effort.

Use small words. Use many if you have to (though fewer is better). This is the method. This is how people connect with your ideas and learn to make them their own. To have impact, a simple phrase, especially one that contrasts against people’s expectations, is better.

Nike said, “Just do it.” It didn’t say, “Execute and energize your peak performance.” Can you imagine that as their slogan? And yet many a corporation uses such words.

If I talk to the stupidest person in the room, am I risking the rest of the audience? Using small words doesn’t attract small minds. Small words are a way to seed ideas in anyone’s mind without creating unnecessary barriers.

The truth is this: Your choice of words and your choice of description aren’t the secret sauce of the idea. They are the wind that carries the paper airplane to its destination. Your words must serve the idea. That’s all.

In researching this part of the book, we thought we’d go find a pithy sentence from an actual six-year-old and point out that it’s obviously well said. That would really have summed up our point. What we found, instead, was interesting. There are many Web sites and many jokes and many hours spent trying to cast children saying something innocently for the sake of a joke. In each of these cases, the child is portrayed as a simpleton and not the creative mind he or she truly is.

That perception, written repeatedly into jokes, may be an even better illustrator of the fear that “Tell it to me like I’m six years old” will lead people to think simple thoughts. So let’s go about this another way.

Take a moment and write answers to the following exercises, using no more than twenty words of no more than two syllables. Try it. Seriously. Don’t just skip the section and keep reading. Anyone could do that.

Describe what you do for work. Describe what your company does.

Describe what you do for work. Describe what your company does.

Describe the movie The Matrix.

Describe the movie The Matrix.

If we gave you five million dollars, what would you do with it?

If we gave you five million dollars, what would you do with it?

What is your personal philosophy?

What is your personal philosophy?

What do you want most in a new hire or colleague?

What do you want most in a new hire or colleague?

It’s tricky, isn’t it? The urge to use large words or complicated explanations is worth policing. If you can’t say something simply, what are the odds that someone else will understand it any better?

Examples of and coaching on how to better articulate your ideas are all around you.

While writing this part, Chris went away to a yoga retreat. His instructor, Rolf Gates (who is also a kind of Ken Hadge), explained a complex philosophical and psychological term, asmita, as the “mind made me.” The premise has something to do with how your ego builds all kinds of prisons for you. For instance, your belief that you will never get out of debt is a prison you created for yourself. There’s obviously no real reason why this should be true. But think of that simple phrase: “mind made me.” I am the “me” that my mind has created, and once I accept this, the premise goes, I should be able to step outside that perspective and learn more.

Now take that concept, built off those three words (all one syllable, by the way), and try explaining that to your kid. Talk about what it means to be self-censoring in language a kid would understand. Practice this.

The more you learn how to express yourself using the Ken Hadge method, the more you’ll be able to deliver a strong message. We’ll talk about another idea on Articulation that builds on this.

THE FIERCE EDITOR

How many words do you need to express your idea? Here’s a hint: That last sentence was probably too long. Part of learning Articulation is learning which words to choose. Another is learning which words to lose. And yet another is understanding when you have to explain something a little bit more for it to make sense and be useful. We need a fierce editor, and barring hiring someone for this, you’ve got the job.

We need venture no further than our in-box to see examples of all three situations. Look at your sent items. Have you sent a long e-mail that could’ve been pared down to a hundred or fewer words and gotten your point across? Have you sent an e-mail using too few words that resulted in a ping-pong game requiring you to check your in-box ten times? Now is the time to fix these problems.

One of our favorite Web sites, http://two.sentenc.es/, focuses on this concept by asking senders of all e-mail to restrict themselves to text message–like lengths. When concepts don’t fit into this structure, they can be addressed in a phone conversation, a blog post, or some other form of media. But the larger point is that format should be dictated by need, and restrictions can actually help you become better with your message.

Have you been to a Chipotle restaurant? The process is spread across four big signs behind the cash register and preparation area: “ORDER” (a particular format for serving the food), “WITH” (a meat type or vegetarian), “SALSAS” (sauces and what they cost), and “EXTRAS” (chips and guacamole). You can figure out rather quickly how to order. There are only five or six ways to do it. There are only four meat options and one vegetarian in “WITH.” You can pick a few sauces and extras. It’s a flow. The flow exists on the boards. It’s somehow even easier than the typical fast-food menu.

But this language and messaging is in everything Chipotle does. Have you seen its advertising? Swing by Chipotle.com and click the “Back to the Start” link (if it’s still there when you finally read this book). It tells a video story of Chipotle’s commitment to fresh food. It is articulate and simple, told with cute-but-vibrant animation talking about why fresh and local food is better for all parties. It’s clear that Chipotle wants its ideas heard, understood, and embraced as our own.

Can you articulate what you sell in just a few simple boards with very few words? If not, why not?

One of the main reasons there is still a huge difference between a blog post and a complete, mainstream book is that a book must work harder, much harder in fact, at connecting the dots.

The very concept of connecting the dots is human. It’s something that can’t be done by machines but that humans are very good at. Think about it. Where a human being could fill in the blanks and see a lion after putting some of the dots together, a machine might not see anything. So a big part of creating clarity in your idea is connecting the right dots.

A group of blog posts could be a disparate set of ideas that don’t necessarily mesh well. Publishing them as a book would be like adding the details of a painting before the big picture, like adding stars before painting in a sky, or painting a tree, a river, and a mountain but nothing in between to make them into a landscape. As short ideas, they each work well, but they’re nothing you could sell on the art market or hang in a museum (unless the drawing were part of a larger story). Books, or any final, completed media, have high Articulation because they explicitly connect the dots among multiple ideas in order to create a final, concrete explanation.

Connecting the dots gives you a ten-thousand-foot view. It brings together a whole picture, which is much more easily comprehensible. It lets you start at the beginning instead of in the middle, making it less likely you’ll end up confused by what’s going on. In other words, it gives your big idea, your marketing campaign—whatever it is you’re working on—a sense of context.

Let’s take an example. For years, a real estate agent’s blog could talk about housing prices, renovations of kitchens and bathrooms, backyards, and different neighborhoods. Only later could this become a cohesive, sellable idea such as “The Complete Guide to Selling Your House in Boston.” This final product could have connections that are lacking in each small tip you would find on the blog or get from the agent in person.

But adding length and depth isn’t the only way to connect ideas into a collective, larger whole. If we were to simply collect every fact about the American Civil War into a book, for example, we would have something that could easily fill a thousand or more pages. So one of the most important skills in connecting the dots isn’t just putting everything together, which can be done by machines. It’s the process of synthesis, which requires a smart human or two to look at the whole and decide what really matters, what needs to be kept, what needs to be removed, and what two or more pieces can simply be combined into a new whole. In the book Five Minds for the Future, Harvard professor Howard Gardner calls synthesis one of the five critical skills necessary to distinguish yourself from both peers and machines.

Here’s a quick guide to connecting the dots to help you create a better final portrait of your idea.

1. Get data from more varied sources. It’s easy to read everything that everyone in real estate has already read and create a product from it, but that’s the product of a machine, not a human being. But if you’re making a product like How Harry Potter Is Like Real Estate, then you have a bunch of data sources that other people haven’t considered. And connecting weird dots isn’t just about grabbing a bunch of data from unexpected places. It’s also how humor works—the unexpected, when well timed, is usually very funny.

2. Find unexpected patterns. There are patterns everywhere. If you look carefully you can see, for example, correlations between how well the economy is doing and the size of shoulder pads in suit jackets. Putting together different concepts under the umbrella of a pattern is what we did with this book, for example. This relates to number 1 as well, because finding patterns means getting more data from more places.

3. Remove the irrelevant. Does your work need to have absolutely every example, or can many be removed if you find one perfect example? The problem with lots of the work out there is that it relates the same thing again and again without adding new information. This is subject to opinion, of course, but in many cases finding patterns (number 2) can allow you to remove many repetitive examples and replace them with a single one.

4. Add random data. The human brain is an amazing pattern-recognition machine. If you ever need an idea for anything whatsoever or need to see an old idea in a new light, attempt to add random data and see how your mind connects it to the old stuff. This is a known technique discussed by lots of creatives, such as Edward de Bono, as well as Brian Eno with his Oblique Strategies cards.

There are more methods, but they all focus on the same idea. Take disparate concepts and connect them. Take a look at what the new, combined concept is like. Give it a name and simplify it. Then do it again, somewhere else, until the concept is simple and perfect.

#

If you’re like us, you probably started on the Web quite a few years ago. You may blog, but intermittently. You’re not “a writer” necessarily, or at least you don’t call yourself one. You may have a university degree in literature or something, which means you had to write long essays at some point, but that was a long time ago. You’re definitely no longer accustomed to writing on a regular basis, and this probably means you think you’re terrible at it—and hey, you may be right!

We’re not here to berate you about not writing, but we will tell you this: Writing is now one of the few skills you must have—and we really mean “must” here—for the twenty-first century.

Think about it: More and more of our content is consumed online. It gets sent to your mobile phone, your tablet, or your computer. We consume more written media than we ever have in history. Do you sincerely think this trend is going to suddenly reverse itself? It’s time for all of us to become master copywriters. Many Web aficionados are already doing it. They’re learning to master written sales techniques that get amazing results for any half-decent product they come across. As they get better at it, in some cases they are literally creating their own jobs by becoming better salespeople and persuaders.

Meanwhile most of us are sitting around, passively consuming content instead of creating it. Actually, it makes us kind of angry just thinking about the wasted potential. Maybe it has the same effect on you. We hope so, because it really is that important to learn.

Writing proper, excellent copy is going to be one of the most important tools in your attempt to conquer the world with the stuff you make. If you can write well and sell well, you can build an audience and make requests of them more often.

If you don’t know how to do these things, though, you’ll find yourself more dependent on others. Your channel won’t get much attention and you won’t know how to develop it. Or even if you have one with a significant audience, you won’t know how to sell them something. So you must learn to convince with your words.

To do this, you really have to become a master of language. This takes a lot of practice, and we can’t do the work for you. So for now, here are some 101-level tips.

1. Learn to freaking spell. Does this really need an explanation? Sincerely, this is important. Misspellings have a huge impact on credibility (a factor in Trust, discussed later). At the minimum, use a spell-checker. This is basic.

2. Expand your vocabulary. The magic of e-readers is that they typically include a dictionary. Click and highlight and you have a definition, instantly. How better to improve your understanding of your own language? Imagine how clunky it was to do this a hundred years ago and rejoice. Any time you don’t know a word, don’t think twice. Just do it.

3. Study the masters. Copywriters have sold hundreds of thousands of books to people like you and me because selling through writing is their art form. They have perfected it to such a degree that the writing seems natural and easy, all the while subtly convincing you. So study them!

4. Copy a masterwork. When Julien first remarked on his blog that he was doing this, it seemed nuts (and the comments said so). But some of the best-known writers of our time have done it. Haruki Murakami has translated a ton of English-language works into Japanese and is now considered one of the world’s greatest living writers. And Hunter S. Thompson, during his tenure at Time magazine, typed out Ernest Hemingway’s and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books on a typewriter. Copying a masterwork isn’t as crazy as it seems.

5. Write endlessly. Nothing works better to improve writing than making time for it every day. Free yourself from the constraints of perfectionism by writing something you’ve deliberately decided you’ll never read ever again or perhaps even decided to destroy afterward. Or, practice free-form writing and then editing afterward, but not together—they are usually incompatible.

We often hear from people that they have “too many ideas.” They might start working on an idea to build a Web site that helps bands find better rehearsal spaces, but before they finish, they get a new idea to import different types of tea from Barbados and begin working on an import/export business. Midway through that, they have a great idea for how to really improve Netflix, if only they could meet the right person and talk about it.

Everyone can suffer from this, if they choose to let their ideas run rampant. Chris did this a lot in late 2010 and into 2011, and it had quite a negative impact on his business. He would run with something, feeling very entrepreneurial about it, and never quite get the execution just right before he started in on something else. Julien’s had his share of ideas that have started and stopped too. When exposed to the Web, it’s natural. Lots of ideas seem exciting, but the ability to focus is really what matters.

Having too many great ideas is really part of the process. From there, you must pick an idea or a few ideas and work them from raw thought into something that might deliver value. And again, you can look at “idea” as meaning “project” or “thought you want to communicate” or “mission” or many other things. It all works out the same.

Having too many ideas is a starting point. Next you might decide upon a framework to determine which ideas are worth acting upon. That’s where most people miss a step.

There are many ways to tackle this, and which is best ultimately depends on what types of ideas you’re talking about and what your goals are. Let’s look at a few frameworks and talk about how they might work for you.

Business Ideas

If you want a way to evaluate business ideas, you might build a framework like this:

Does this idea fit our mission and goals for the year and beyond?

Does this idea fit our mission and goals for the year and beyond?

Is the new idea revenue generating (or cost cutting)?

Is the new idea revenue generating (or cost cutting)?

What would it take (money/time/resources) to get the idea launched?

What would it take (money/time/resources) to get the idea launched?

Who would champion this idea and do they have time?

Who would champion this idea and do they have time?

Assuming we’re working at 100 percent capacity right now, what would have to go to make room for this idea?

Assuming we’re working at 100 percent capacity right now, what would have to go to make room for this idea?

How much money could we potentially make (a conservative estimate), and is it worth it?

How much money could we potentially make (a conservative estimate), and is it worth it?

Looking at that set of questions, you can see how to phase out “too many ideas.” You might have an idea that meets a few of the above criteria, but you’ll see rather quickly why it won’t be worth pursuing if it doesn’t do well on the others. If you do this often enough, you’ll end up with just the correct amount of ideas, and the right ones.

Creative Ideas

If you’re an artist or musician or some other creative role, maybe you need a way to determine whether to pursue a project idea. Your determining factors might be different. Let’s look at a sampling.

Does this idea connect with any of the themes of my work?

Does this idea connect with any of the themes of my work?

Does this idea stretch me as an artist, or is it a repetition?

Does this idea stretch me as an artist, or is it a repetition?

Can I use my skills to execute this idea?

Can I use my skills to execute this idea?

How much time and other materials are involved in this idea?

How much time and other materials are involved in this idea?

Do I care whether this idea is salable or not?

Do I care whether this idea is salable or not?

The best possible way to sift through the abundance of ideas in your head is to work through a framework of questions that will help you determine what works best for you and your pursuits. Again, the questions really will vary. A creative person might not care whether a project is revenue generating but might care a great deal about whether an idea stretches his or her skills or abilities.

Another problem with having too many ideas is that we have to be very conscious of the value of time. You might have a great idea, think it through, give it a pass through your framework, and launch it to your platform. But what if you don’t give it enough time to get off the ground? Or, in another time-related perspective, what if your idea is only really viable for a brief amount of time?

Thinking through the potential longevity of an idea is another good way to “gate” these opportunities and decide whether or not to give them a go. Chris once launched a project where he intended to shoot video reviews during all his business travels. The project presumed that Chris would be on the road quite often (which at the moment was true). Shortly afterward, Chris reduced his time on the road, and the project collapsed. If he’d thought about the idea’s long-term staying power, he might not have launched the project and left another orphaned site out there on the Web.

Thinking through the timing of ideas will help you reduce “too many ideas” to a workable number.

Imagine you’re tasked with creating a movie. You decide it should have giant robots. You then decide it should also have Greek gods and mythology. Then you add 1930s-style gangsters. Finally, you determine it should be a musical. Odds are, it won’t work.

The same is true of having too many ideas. It’s important to apply constraints to what you’re doing. Said another way: By sticking to one strong theme or story, you’ll have a better chance of limiting your ideas to those that are more promising.

The beauty of constraints is that they let you work within a certain set of parameters and cull extraneous “noise.” If you decide to improve your physical health over the next several months by taking up running and body-weight exercises, it might not be useful to also take up basketball. You might decide to rule out the idea of getting a new mountain bike, because that isn’t running, nor is it body-weight exercises.

Similarly, with a bigger idea, you can ask whether it fits the story you intend to tell. If you’ve decided to focus your efforts on selling video projects to big companies, starting a small business consultancy doesn’t match. This kind of story-based thinking allows you to rule out some of those “too many ideas” quite easily.

#

At the time of this writing, tablet computers and smart phones have overtaken both laptops and desktops as the communication and consumption devices of choice. People are no longer comfortably reading your very long and rambling e-mail at their desk. They are reading it on the way to the bathroom in between meetings. They are reading it while on hold for a conference call. They are almost always reading it in a distracted and time-crunched moment of the day.

Think about yourself: That’s when you read e-mails now, right? You almost never sit down with a steaming mug of coffee, give a delighted sigh of contentment, stretch your neck muscles, and dig into your in-box. Instead, you quickly scan to make sure the boss or your clients or your significant other haven’t thrown something new on your plate.

Worse still, if the mail you’ve sent to someone else was too long, they’ve clicked it as read without finishing it, and now it’s sitting in the gray, no-longer-bold, below-the-interesting-and-unread-stuff no-man’s-land part of the in-box (or worse, it’s filed away!). You can forget about a response if that’s where your mail landed.

But what happened? Why did the recipient forget about you? Don’t you deserve at least the courtesy of a response?

Let’s ask some questions:

Was your subject line obvious and actionable? Could the recipient answer based almost entirely on it?

Was your subject line obvious and actionable? Could the recipient answer based almost entirely on it?

Did you put the most important part of the e-mail in the first paragraph?

Did you put the most important part of the e-mail in the first paragraph?

Did you end the e-mail with the one question that was most important?

Did you end the e-mail with the one question that was most important?

Was there one “ask” in that e-mail or more than one?

Was there one “ask” in that e-mail or more than one?

Was the e-mail HTML formatted and sent via a “donotreply@” e-mail address? (That is, was it a newsletter?)

Was the e-mail HTML formatted and sent via a “donotreply@” e-mail address? (That is, was it a newsletter?)

Had you messaged the recipient recently (within a few months) without making an ask?

Had you messaged the recipient recently (within a few months) without making an ask?

Was the e-mail fewer than three hundred words?

Was the e-mail fewer than three hundred words?

Could the recipient read it in under thirty seconds?

Could the recipient read it in under thirty seconds?

There are several reasons why people have stopped responding to e-mail in a timely fashion, and most of them revolve around too much e-mail in their box and e-mail becoming less and less easy to answer. Hint: If SMS text messaging is on the rise, why would you still send 1,400-word e-mails?

Making a point is easier if you’re brief. Sometimes doing this makes people nervous. Teachers told them to write long, flowing sentences that show off their ability to produce great prose that stacks up against the likes of Herman Melville and prove, once and for all, that they understand grammar.

Phooey. Write brief sentences. Need help getting into it? Read The Shipping News by Annie Proulx. No, it has nothing to do with business. It’s fiction. It’s a few years old at this point. Whatever. It will cure you of the need to write superlong sentences.

The rule of grammar and paragraphs is to write three sentences per paragraph at minimum.

Phooey part two.

Welcome to the land of skimmers. If your idea is packed into a dense thicket of words, it’s lost. The faster you can shave off the fat and get to the point, the faster you’ll see your e-mail response rate go back up.

Articulation and brevity go hand in hand. If someone is to understand your idea, it has to be in a very tight package.

Could you say it in three words?

It’s much harder than you think to do this, by the way. For example, Chris’s company, Human Business Works, is a strategic advisory company that helps midsize to large businesses with customer acquisition via the digital channel. Blah blah blah. Say that in three words?

“Digital marketing strategy.” It’s a whole lot harder to sell with just those three words. That said, if we put that in the first line of an e-mail, it’s a lot more likely to get read than blabber about customer acquisition and the rest of it. See how this works?

If you can’t simplify words, lines, and syntax and make your writing clearer for people to respond to, you are doomed.

Do you see how we wrote this section mostly to demonstrate what we’re aiming for in your e-mail efforts? (If you’re listening to the audio program, that’s probably a “no,” but pretend we’ve written very brief, simple, punchy sentences with lots of tiny paragraphs instead of longer ones. Fair?)

Articulation will help you see responses.

CLARITY AS A FORM OF CONTRAST

If you’re good enough at it, it’s possible that high Articulation (or clarity) in your message may in fact be enough of a differentiator to put you over the top—from invisible to visible, from zero impact to high impact.

When Stephen Hawking came out with A Brief History of Time, there had never before been such a clear expression of how the universe and time work. Yet the ideas were not new. Only their expression and packaging were. In this case, it was enough.

Consider the originally submitted title, From Big Bang to Black Holes. It clearly conveys what the book is about yet leaves you with no impression of the subject’s grandeur. Graphics inside help you truly understand how the four dimensions work. Opening it leaves you with the immediate impression that, yes, you can learn this stuff.

Combined with his important brand in the space (no pun intended), Hawking was able to create the first mass-market physics book, eventually selling over ten million copies and staying on best-seller lists for four years.

Here’s how to use high clarity to differentiate yourself.

Value clarification: “How to Gain a Thousand Twitter Followers in One Hour.” Putting the value proposition in the title often tells people exactly what they need to hear. If this is something your audience has been meaning to figure out, they’ll see it and care immediately. So you can gain an advantage just by clarifying.

Data visualization: If 2008 was perhaps the year of the top-ten list on the Web, 2011 could have been called the year of the infographic. Known to initiates as data visualization, infographics have caught on in a big way on the Web because of their ability to clarify data (and sometimes mislead with it, actually). Will they still work by the time you have your hands on this? Test them out and see.

Condensed or expanded content: Make what you do extremely concise and clear or extremely long and profoundly explained. Either method is a form of clarity if properly used. Viperchill.com, a blog run by the South African Glen Allsopp, produces material so long that his twenty thousand subscribers can’t help but feel that every article is a super-comprehensive, well-researched guide (and it is). On the other end of the spectrum, Seth Godin produces content so dense that practically every line is spreadable on its own without further explanation. Either of these options is better than middle of the road, where nothing much happens that’s exceptional at all.

Because we’re both in business for ourselves and seem reasonably successful, friends and strangers alike want to tell us their business ideas. Quite often, they’re hoping for validation, and then, a lot of times, they ask us to participate in some way. (We usually have to decline, because our plates are full.) In hearing a lot of these ideas, we’ve come to know a bit about how some people frame their concept of a business.

If I Need It, Someone Else Will Too

We hear ideas like this one all the time: “I was in the market for a bonsai tree, and then I realized that there aren’t really any good bonsai tree–selection Web sites out there, ones that really cater to someone interested in starting from scratch. So I’m going to start that business.” Okay, before we go too far, it’s important to realize that there’s a niche for everyone, and before you discount someone’s business idea because it seems too quirky, remember that there are many people out there who are completely successful doing strange businesses you wouldn’t believe. And yet there are some points to consider.

An idea for a business isn’t good just because you yourself have a need. You might have to validate whether or not others are showing signs of the same need. However, to paraphrase Henry Ford, most people thought they needed faster horses, not automobiles. You might not be able to find evidence that people have a need like yours. You might have to create a prototype and get a few people to test the concept. And “a few people” might mean thousands. It depends on the product or service.

There are other ways to get into a bit of a bind when thinking about business ideas.

I Really Understand These People, so I Can Sell to Them

We’ve lost track of how many people (usually in their twenties) tell us about their ideas to help bands. We used to be a lot more polite while listening to these ideas, but after a while, they all kind of blur. Our most common answer when we’re given a chance to reply: “Bands don’t have money.”

Quite simply, just because you are from the same demographic you’re hoping to sell to or believe you’re attuned to a certain market segment, that doesn’t mean your idea will have business value. Bands, as we’ve pointed out, don’t have money. If you’ve created the ultimate band-promotion site (which has been done successfully several times, by the way), you’ll have to find a way to extract money from some other segment. Think just a moment longer about this example. Audiences don’t like to pay. Heck, they barely like to pay for music. Will the record labels pay? Not likely. Not often. They have a “not invented here” bias problem. So what do you have? An amazing idea that won’t make you money.

I’m Really Good at This, so I Can Do a Business

We feel like we’re stealing from Michael Gerber’s E-Myth books, but hey, if you’re a great cook, it doesn’t mean you’re a great businessperson. The skill set required to cook has nothing to do with the skills required to market a restaurant, get more customers in, and improve your margins while not watering down your product.

There are people who are really good at painting portraits or quirky street art, but there’s a reason people talk about being a “starving artist.” Art either sells remarkably well or it doesn’t. And you don’t have time to sell posthumously.

There are many variations on this particular idea problem. People tend to mistake their aptitude as a shoo-in for business success. There really are some great accordion players out there. We can name one: Weird Al. See where we’re headed with this one?

Ways to Reshape Your Business Ideas

One easy way to determine whether your business idea is potentially viable is to run through this quick checklist:

Do I have a market for this? Do I know how to reach the people who might want this?

Do I have a market for this? Do I know how to reach the people who might want this?

Do I have the resources and time and proclivity to do this? (Remember your goals from part 1, and ask if this aligns with them.)

Do I have the resources and time and proclivity to do this? (Remember your goals from part 1, and ask if this aligns with them.)

Is this something people will pay for? (This one often seems to be skipped in people’s assessments.)

Is this something people will pay for? (This one often seems to be skipped in people’s assessments.)

How sustainable is this business? Can I do it for a while?

How sustainable is this business? Can I do it for a while?

Is this business salable? Can I turn it over to someone later on?

Is this business salable? Can I turn it over to someone later on?

You can choose to answer these questions however you like. If you’re part of a larger company, you might modify them to meet your needs. If you are a sole proprietor or the owner of a smaller business, you might face these questions quite often. Remember that if you replace “business idea” with “new product or service,” a lot of the same questions apply to established companies.

Chris hasn’t been very successful at building salable businesses. His business ideas tend to revolve around his abilities and experience, which obviously don’t translate to something one can walk away from. Julien has been fortunate in this regard. But it’s definitely something to consider, if it’s your business and you want to find ways to grow your potential.

There are dozens (hundreds? thousands?) of people who will tell you that your idea will never work. There are just as many people who believe you are doing the same thing that others have done before. Every time you hear this, smile politely. There were many airlines when Sir Richard Branson launched Virgin, and he did great. There were many people selling MP3 players when Apple (then failing and most definitely not a “sure thing”) launched the iPod. There were many people selling personal-improvement seminars and educational materials when Tony Robbins did so and went on to become wildly successful.

For every person who tells you why you can’t accomplish a business idea, including us, be true to yourself. There are so many rejection-letter-to-now-very-obviously-successful-person stories out there that we refuse to list them here. Any one of them tells the same story: Hundreds of people said this person couldn’t do it, and then they went on to be one of the most amazing whatevers in the history of that segment.

That can be you. Work on your idea. Work on building your platform. Understand the human element. Build your own Impact Equation around all this, and you’ll find a way to make ideas that matter.

#

People who doodle get a bad rap. Are you a doodler? We are. If anyone has ever questioned whether you were paying attention because you were shading your stick-man Batman in the margin, never fear. We think there are many ways to use visual thinking to improve your ideas.

Have you tried mind mapping yet? This is the act of moving your ideas around visually. It’s a great way to open up your thought processes to the logical flow of ideas.

The basic technique is that you take a blank piece of paper (there are also hundreds of software applications written for this same function—we use XMind and MindNode), and you draw a smallish oval in the middle of the page. Here you put your primary idea. Maybe it’s “popular Web video show.”

From that main circle, draw a line or a branch and pop up another oval, where you might put down “barriers to success.” From that branch, add another oval that lists “lack of funds,” “no skill in making video,” “really ugly looking,” and the like, one idea per oval.

Then go in another direction with a new branch, and write “subjects for video.” Splitting up that branch into its many possibilities, begin with writing “football” and split that up into “NFL” and “college.” Then go back to your “subject” options and write “hockey” and split that one up into its branches as well.

Mind mapping is basically visual note taking that ends up significantly more powerful than traditional methods. It lets you think through ideas in a visual way, work through possibilities, and see all their contingencies. You can create mind maps with many different uses. You can build them to test out an idea, to make sure you’ve thought through an idea, to decide what else will need to happen for an idea to be successful, and more.

Julien uses mind maps to map out blog posts and with games he runs with friends. They work because they fit the way the brain has ideas, by connecting one to another. They’re also much better than simply thinking because they allow you to go back to concepts you’ve left behind and develop them later.

As Chris started adding to this part of the book, he realized that his mind-mapping software was open. In it was a little map to think about success:

The thoughts that accompany this mind map were about what it might take to be successful. Are you an actor or a spectator? Are you a lifelong learner or did you “drop out” after you finished your degree? Are you a context shifter or a trench worker (do you see the big picture or details)? Are you a wealth builder (someone who uses money to improve the world) or a bargain hunter (someone worried about scarcity)?

That was one side. On the other side Chris wrote about what the external functions of this person would have to be. He or she would have to believe that his or her secondary function in life was marketing, sales, and customer service to his or her idea. He or she would have to be an expert storyteller who understands how to bring an idea to the campfire (hey, yet another metaphor), and this person would have to be a hero maker, meaning that to truly succeed, one must help others succeed. Finally, a truly successful person must have a strong “no” gate: the ability to say no to opportunities or paths that detract from his or her success.

Using mind maps allows you to build a visual of your ideas. You can do this with paper and a pen. You can do this by drawing. You can think visually in lots of ways. If you want a really interesting book on this process that extends into using visual thinking and games to improve your business, check out Gamestorming by Dave Gray, Sunni Brown, and James Macanufo (see also http://www.gogamestorm.com/). Also be sure to get into Chuck Frey’s Web site (http://www.innovationtools.com/), as he’s the leading authority on all things mind mapping and our go-to person for learning what’s new and interesting in that world.

But don’t stop there. Visual thinking can take many forms. And opening your head up to new ways of forming ideas is just as important as everything else in this book.

Our buddies Hugh MacLeod (gapingvoid.com) and Mars Dorian (marsdorian.com) can boil fascinating ideas down to the back of business cards. Their styles of visual thinking can certainly give you a new way of looking at your idea. And though we’re writing about mind maps specifically, realize that you can get there in many ways. How would a little cartoon change your perspective? Could the “voice” of the cartoon be the voice you’re not yet willing to claim as your own?

What if your mind maps were storyboards instead?

Karen J Lloyd (http://karenjlloyd.com/) writes about storyboarding on her blog and points out that it isn’t just for artists anymore. You might just be someone with a business question the mind map didn’t solve. Why not try “telling the story” with a storyboard?

Not sure how to apply that one? Think about it. What if you were debating whether to move cross-country and take a new job in a town where you have no roots? What would that story look like drawn out in boards? You could talk about what it’s like to reestablish a local network of friends. You can talk about what babysitting issues might arise now that you don’t live near your parents. See how the drawing process shifts your thoughts into a different angle?

Though we both write books, blogs, and other linear, narrative works, we both branch into a variety of types of visual thinking when we consider how to improve our impact. The written sentence can be freeing, such as when you’re journaling to “talk onto paper,” but it can also be limiting, as you must use a certain syntax that is already laden with presumptions. Said another way: It’s sometimes harder to see the alternatives to an opportunity or a challenge if you’re using the written form.

Open your possibilities. Try mind mapping. See what other visual-thinking methods might apply to you. What could it hurt?

In his amazing book Understanding Comics, author and illustrator Scott McCloud explains how emotions get illustrated. He shows how, when your face shows emotion, it usually isn’t a simple expression but a combination of two other simpler feelings. For example, surprise is a combination of fear (eyebrows up) and shock (mouth wide open).

Lots of concepts can be dissected this way—divided in two to make them easier to understand. The movie Alien was first pitched to studio executives as “Jaws in space,” for example. Likewise, we could extend this idea outward, coming up with other “Jaws in…” ideas, such as “Jaws in Africa.” (This might end up being The Ghost and the Darkness, starring Val Kilmer, for example.)

You can use this same method to help you understand yourself, your company, and your project a little better. If you work at it hard enough, you may even get to the core of your message, what you are really about—and expressing it to others will become infinitely easier.

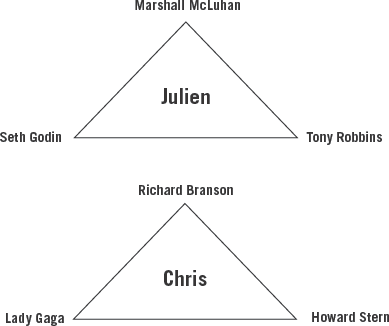

Method 1: The Triangle Method

Imagine a triangle. If you are a company, then each point on the triangle is also a company. If you’re an individual, or if you have a blog, then each point becomes an individual or a blog, respectively. In the middle of this triangle is you.

Think of your triangle as a target, and aim for the middle with the work you do. Keep in mind, it’s okay if you don’t hit the center of this target, as long as you don’t hit entirely outside it.

Now come up with three companies or individuals that will help you aim. For example, a few years ago when Julien first did this exercise, the three individuals who helped keep him on target were Marshall McLuhan, Seth Godin, and Tony Robbins. When he told Chris about the exercise, Chris chose Sir Richard Branson, Lady Gaga, and Howard Stern. (Our choices would be different now, but the point remains the same.)

Now, every time you have a message to articulate, you can remain on target by thinking of your triangle. Are you aiming in the right direction? Is the message written the right way? Or, if you consistently aim outside your target, consider changing your core three.

Method 2: Emotion + Information

This second method is interesting too, but totally different. Do any of these, or all of them if you have the time. Then repeat them a few years later and see how much things have changed.

After you have worked on a few key ideas, consider what the principal information is within them. Usually this can be done by category (social media, business, relationships, etc.). Draw these as circles and see how they overlap, perhaps with a Venn diagram. If you can come up with only one (if, say, you’re all about coffee), then try to distill it into many messages (fair trade, etc.).

Okay, once you have a few of those, think of a few emotions you display them with. This will make you realize that you need to present your ideas with an emotion, or they’ll lack Echo (another Impact Attribute we’ll discuss later). If you’re displaying only information, others simply won’t connect well with it.

One example of this would be the way that Julien wrote The Flinch. People often say it’s written as if by a drill sergeant. What this means is that it’s the information for self-growth alongside the emotion of anger with a smidgen of hope. You’ll notice that combining the information with feelings like sadness and remorse delivers a whole other message for a totally different audience.

Try this out now with your project. If you are delivering a certain message, or if you’re not getting the type of customers you want, ask yourself what emotion you’re placing alongside your message. Is it congruent with whom you want to attract?

Julien once spent a whole conference (three days or so) helping people clarify their identities and the way they introduced themselves. He came across a great tactic that helped almost every single person figure out who they were, whether as an individual, a small firm, or a start-up. The method is deceptively simple but very effective. Here it is.

Begin with a single character, usually (but not necessarily) fictional. It can be a cartoon character known for a specific thing (say, Captain Planet) or a real-life historical figure (like Ulysses S. Grant). It should always be a well-known name but never what we would call an A-list name (such as James Bond), because that sounds like bragging. Choose someone you admire or look up to.

Then decide what industry you would like to be part of. Political bloggers, MBAs, and others will each have their own answer to this question. Whatever industry you choose, make sure it’s where you want to work or a place where other people would like to be, because this method is about catching people’s interest.

Then, combine the two into “the X of Y.” Simple.

The result of this exercise is almost always a self-definition that is more interesting than what you previously had. For example, one Harvard Business Review writer became the MacGyver of innovation. (She puts small, distinct pieces together into a much better whole.) You yourself could become the Aquaman of globalization (bringing together two separate worlds (water and air) and helping them make sense together). But whatever it is you come up with, we guarantee it will be better than how you previously introduced yourself. Try it.

ARTICULATION: HOW TO RATE YOURSELF

How clear is your idea? This is an important section of the equation because you only get one chance to leave a strong impression. Consider it your elevator pitch. Will your one chance, right this instant, result in a clear impression in your target’s head, or will you end up looking embarrassed trying to explain what you do or what your idea is?

Ideas no longer get second chances. We need to know how to express ourselves clearly the first time.

Now, we assume that other parts of your concept aren’t hindering people from understanding your idea. For example, when someone says, “How is this different from all the other blogs about social media?” they’re asking about Contrast, not clarity. In this example, they know what you do; they just think it’s deeply boring (and they may be right).

So we want to focus here on the clarification of an idea—making people care not because they’ve never seen it before but because it sticks in their head instantly.

Give your complex idea a name. Simplicity is a key part of clarity, and if you can give an idea a name (Gladwell’s The Tipping Point comes to mind), you capture the imagination much more quickly.

Acronyms: We actually try to resist this idea, because it seems contrived, but we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention it, so here goes. The Impact Attributes are interesting, but placing them in an order that results in the CREATE acronym is a good example that helps make it memorable. We also used this technique when we reformulated the David Maister, Charles Green, and Robert Galford Trust Equation in our last book. So T=C*R*I/S became C*R*I/S = T. Generally, ideas that use human mnemonic devices are more memorable and clear than almost any other ideas, because we are verbal creatures who learn based on narrative and story.

Tell a story: Any time you express a complex idea, this is one way to simplify it. We naturally learn through stories and metaphors, so expressing ideas with them is simple and effective. This is why those terrible “business parable” books sell so well; they express simple ideas through narrative. Whether the story is real or imagined is actually irrelevant (some say the story in Robert Kiyosaki’s Rich Dad Poor Dad never happened, for example); what matters is whether it resonates emotionally with the reader. We’ll return to these concepts later in our discussion of Echo, but for now, remember that proper Articulation of an idea keeps it memorable.

One great example of Articulation comes to us from Chrysler, which has, interestingly, relaunched the Fiat brand in the United States. The company capitalized on the marketplace reopened by the Mini Cooper, as well as on U.S. gas prices, and brought back a car that hadn’t been viewed as anything particularly notable before. How does Chrysler articulate what you’re buying into on its site?

It mentions “Italian style,” “emotional design,” “rational appeal,” and a lot of personalization options. In a few short phrases, you get a sense of what Chrysler wants you to know about its car.

Swing over to the Mini site, and its language is about “incredible gas mileage,” “premium technology,” “legendary performance,” and “smiling.”

A car purchase is an interesting way to think about Articulation. It is an exercise in justification from start to finish. If you’ve gone without a car for a long while, you must justify why you now need to buy one again. If you’ve got an older but still functional car, you have to justify why you’re upgrading or replacing it. Buying a sports car versus an economy car requires a story told to oneself, and then sometimes the rest of the family.

It gets interesting when a car’s advertising must speak to the passionate reason why we’re really buying the car while arming us with the information we’ll need to make others in our decision-making circle (or only ourselves) feel good about the decision.

Both Fiat and Mini talk about how their cars are economical and fuel efficient, yet they both rave about their design and performance capabilities. They cover both bases, and each Web site’s ad copy, by the way, does it with fewer than fourteen words.

We’ve talked about brevity a lot throughout the book, but its value can’t be highlighted enough. In every case where you seek to get a point across, brevity is a core selling point. It will get you much further than trying to paint with words. You’ll see.

IMPACT EXAMPLE: INSTAGRAM

On the day the news broke that social-networking giant Facebook was buying photo-sharing application Instagram for one billion dollars, opinions on why and what next were quite mixed. We were split in our opinions. Julien thought it was a great purchase and cited the thirty million acquired users, plus the revitalization of photo sharing, which had reportedly been dwindling on Facebook’s own platform, never mind the fact that Facebook seemed genuinely threatened by Instagram’s dominance of mobile photo sharing. Chris dug into some reporting that said Instagram might be an angle Facebook could use to break into China.1 We decided to look at Instagram to see how it matched up against the Impact Equation.

Contrast: There are hundreds (thousands, actually!) of photo applications in the Apple and Android stores. Instagram, however, backed its app with a social network, so people could follow certain tags, certain photographers, and more. Tying an application to a network of like-minded people made for good Contrast, but it wasn’t enough. Only when the founders had made their third photo application, simplifying every time, did they get to something that had the Contrast it needed to win.

Reach: If Instagram really is the gateway drug to get Facebook into China, that’s a great way to extend Reach. Even if that isn’t the case, Facebook purchased thirty million passionate Instagram users and gave its photo-sharing credentials a powerful shot in the arm. Since they are leaving Instagram be, there is no question it will continue growing.

Exposure: Facebook’s brand isn’t mentioned at all inside of Instagram, but that doesn’t matter. To the users who care, Instagram is a more highly valued brand, and every time a new, great picture appears, Instagram gets a shot of Exposure.

Articulation: Instagram is an almost perfectly simple application. Take, edit, and share photos. Photos, if you think about it, are a great currency for social networking. What do we like to share? We love sharing photos of our kids, our new cars, our whatever. The app’s social network is simple to articulate too. It’s not nearly as complex as Facebook or Google+. People who like sharing photos congregate there. Instagram gets high marks in Articulation.

Trust: Does Instagram have our Trust? It probably would rank higher in a survey than its new parent company. Facebook goes in and out of public favor with privacy issues and other conundrums that shake its users’ comfort levels. Instagram? It has earned Trust over the last few years. It was a very big seller on Android’s marketplace in its first few weeks on that platform, ranking number three overall at its zenith. That says something.

Echo: Do you see yourself in Instagram? This is a no-brainer. The application is built to let you take, edit, and share photos from your life. Chris’s joke is that Instagram turns your otherwise boring life into album cover art. Instagram also earns Echo by mapping into all kinds of social networks besides Facebook, thus creating a bridge between the application and wherever your crowd is.

We rank Instagram as a highly successful user of the Impact Attributes. You might be lucky enough to have Facebook come and offer you a billion dollars for your company, but if not, think about how Instagram worked its Contrast and how it articulated the value of the product. You might not have thirty million users or customers, but you can certainly benefit from thinking about how adding some kind of user-to-user social experience might help your product grow.

It’s early in the acquisition, but we think it will be a smooth integration and people will extend their use of photo-based networking and sharing even more with this product. A picture is worth a thousand words, they say, but evidently, it’s also worth a billion dollars.

1 Source: http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2012/04/10/will-instagram-help-facebook-crack-china/.