Recovering the Intergendered Soul

Conscious femininity is not bound to gender. It belongs to both men and women. Although in the history of the arts, men have articulated their femininity far more than women, women now are becoming custodians of their own feminine consciousness. For centuries, men have projected their inner image of femininity, raising it to a consciousness that left women who accepted the projection separated from their own reality. They became artifacts rather than people. The consciousness attributed to them was a consciousness projected onto them. That projection was sometimes an idealized image of beauty and truth, a sphinx, or a dragon. Whatever it was, it could not be an incarnated woman.

—Marion Woodman (1993, 1–2)

The first stories in this chapter depict the excavation and return of soul parts of women. I include a story of mine that involves the return of a young boy image. I have reflected a great deal on this image of a dark boy, age somewhere between seven and eleven, not quite a child, on the verge of adolescence. Carol Gilligan and her colleagues at the Harvard Project on the Psychology of Women and the Development of Girls have conducted numerous studies that catalogue the reality of girls, their loss of an authentic voice, at about the age of my boy (1991). They document the social pressure on girls to domesticate, to submit to expectations of docility and agreeableness, and how this leads to an absence of self. Lyn Mikel Brown, a member of the Harvard Project on the Psychology of Women and the Development of Girls, describes the alternative: “A girl who chooses to authorize her own life experiences by speaking openly about them resists the security of convention and moves into uncharted territory; she sets herself adrift, disconnects from the mainland; she risks being, for a time, storyless” (in Gilligan 1991, 72). The stories in this chapter reveal women for whom art made an alternative story possible in adolescence, but whose lack of some crucial element prevented the artist’s story from coming to fruition until years later.

My image provoked me to ask: What are boys doing during this transitional time that is different from girls? What images do they embody? I began to think about my two younger brothers and also to notice boys in public spaces. My youngest brother would spent time alone throwing a baseball up in the air and catching it in his mitt, all the while narrating a fantasy baseball game to himself. When I was a child, boys could wander home after school, poking sticks into things, turning over rocks, and wading in the brook that ran through town. When I began to do that, too, my parents got in the car and came searching for me, saying such antics were dangerous; “strange men” were known to lurk in out-of-the-way places, waiting for unsuspecting girls. Boys, apparently, were at no such risk.

Watching boys skateboard, I discovered a kind of single-mindedness that translates ultimately into skill. A boy will ride up and down the same stretch of pavement endlessly, practicing his moves for hours. What I observed cued me to what many women lose out on: the development of self-discipline and commitment to a physical task. Ellen Dissanayake, a scholar who has studied the meaning of artmaking behavior for the survival and evolution of our species, says: “Our bodies and minds are adapted to lead a life of physical engagement, and when born into it people find it agreeable, even richly rewarding” (2004, 116). Boys climbing trees or shooting baskets over and over, even when they do so with friends, are not being social or even necessarily competitive. The activity is sufficiently rewarding in itself to be repeated. The sense of focused attention and the resulting skills are very gratifying and bind a boy to the world. The tasks girls are usually expected to repeat, such as housework, have no associated learning or increase in skill, no particular physical challenge that makes them rewarding. For reinforcement, girls learn to rely on being told by someone else that they did a good job and that their acts of service are appreciated.

Girls of my era accepted the tag “tomboy” when they spent hours in the woods or playing a physical game. As Sallie’s story illustrates, such endeavors were usually extinguished by adolescence, when being a freely embodied girl raised the danger of sexual experimentation, which suggested the possibility of acquiring skills that would lead to the choice of an appropriate mate. One could be a good girl or a bad girl; those were the choices. Artmaking requires uninterrupted, self-absorbed time. Kim stopped her artmaking when her son was born; having stained glass, her medium of choice at the time, around seemed dangerous and wasn’t something that could be accomplished in fits and starts between naps and bottles.

Girls trade single-minded inquiry into the physical world for the sphere of relatedness and emotion, another important and highly nuanced realm. As women, we often feel selfish and guilty for devoting time to our art pursuits, until like Sallie’s, our children are grown. As the expectation to think of others before self, to take care of the needs of others and maintain harmony, takes hold in adolescence, a kind of independence atrophies in many women. The current rage for scrapbooking speaks to a kind of ingenious truce: women create on behalf of the family. They can engage with materials and the pleasure of cutting and handling beautiful papers for the unassailable goal of creating, preserving, and in some cases editing, the family narrative. I wonder what future historians will make of these documents.

Art subverts and challenges the separation of the internal realms of male/female, good/bad, active/passive. One must be very focused to create. The studio process instructs us to trade our overdeveloped sense of helpfulness for a compassionate disinterest in what others in the studio are doing. Discipline, the sustained focus on a task to completion, undergirds this challenge for relationally competent women. Art as a spiritual path teaches us a new way to relate, while intention and witness encourage our sense of discipline to grow and develop.

Getting back the boy or tomboy parts of the soul locates women in the realm of active competence. I watched my daughter grow up with the benefit of sports to instill discipline and physical prowess in girls. But given that even female coaches remain trained in a male model, we still have a long way to go to discover and integrate a fluid range of self skills. My daughter confounded her pitching coach, whose usual method of motivation was to encourage girls to compete against one another for speed. She saw her pitching as a form of meditation. When she was pitching well in practice, she experienced the physical flow and total self-absorption that I observed in the skateboarders. Yet her involvement in sports did not inoculate her against the damaging social images of women in our culture. Like many young women, she still struggled to accept her voluptuous body.

As fashion magazines dictate younger and younger, slimmer and slimmer, literally hipless models, I can’t help but notice how much they resemble the physique of the preadolescent boy. Can we engage the boyish, dark, indigenous artist soul imaginally, or must we physically become him? Can we opt for a fluid range of self skills that allow intuition on the ball field and stamina in the studio, and engaged, erotic embodiment in our everyday life? Art can show a path.

The Divine Character: Kim’s Story

I heard about Kim before I met her. The director of the Oak Park Art League, where I was to offer a class in the studio process, told me that Kim, one of the teachers of children’s classes, had asked to cancel her class in order to take mine. I assumed that since she was teaching art that Kim was an active artist herself. It wasn’t until several years later that I learned the significance of Kim’s decision to take the class and begin her soul reunion through art. More than most students, who take a ride on my faith in the process, Kim asked a lot of questions. She seemed incredulous whenever I spoke of the Divine or the Creative Source as all giving. It was as if she couldn’t believe that she could make an intention to ask for what she desired. At one point, when my explanations of intention did not seem to be getting through, I suggested to Kim that it is possible to make an intention to get to know what our intention is. She liked this idea and wrote: I’m open to asking for help in writing my intention. Please give me guidance.

It is always important for us to notice the words we choose and to be as mindful of them as we can be. There is a great deal of instruction embedded in our choice of one word over another. It is often only when we review our writings after some time has elapsed that we can see how language shapes our experience. When Kim writes, “I am open to asking for help,” she is still not asking and so she will not yet receive. The Creative Source, imbued with divine compassion, simply holds us until we are ready. Kim’s witness following that intention struggles with words:

Intention. My intent. My purpose—the reason for which something exists or happens. To have a goal. What do I want to have looked at? Centered. What does this mean? What goal? Guidance what path—where to? I’m open to guidance to making an intention. What are my guides? God is my continuous presence. I look to him always. So, God, what should my intention be? My intention for the next six weeks (the duration of the class) To feel centered—to feel the life force yes and to connect with my life force and let out my feelings inside to let my heart talk about what it is feeling not my head. To have pleasure to feel pleasure with my heart. Get rid of the judge—love instead.

Much of what Kim wrote arose from her engagement with the unfamiliar concepts I presented in the class. She writes out definitions as her mind balks at ideas that don’t seem to fit her expectation of an art class or perhaps of spirituality, either. It is not uncommon for newcomers to the process to find themselves teary eyed when I describe the Creative Source as compassionate, as eager to grant our desires. Everyone is familiar with the adage “be careful what you wish for.” Especially when I suggest the idea of pleasure as a path to divine wisdom, I often notice a physical response as shoulders drop, deep sighs unfold, and again, tears rise up. The final line of Kim’s witness expresses the deep question at the heart of her confusion. She writes: What about the child in me and growing older, are they together?

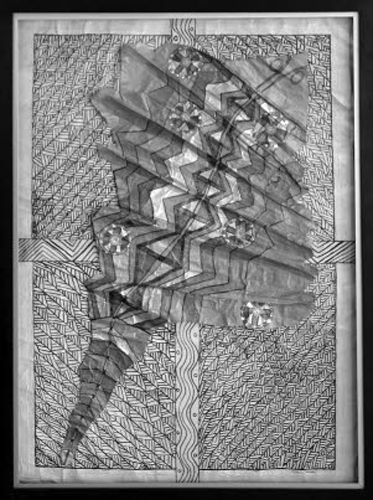

Kim had majored in art as an undergraduate and had the usual art school ideas about materials and what constitutes “real” art. She went along with the idea of just making marks on paper and painting without an image or idea for reference; but when I introduced tape and foil as a sculpture medium, that was the last straw. As is often the case, the material that she disliked most yielded her first breakthrough in the process. I had never seen anyone use tape and foil the way Kim did. She covered large flat pieces of foil with tape as if a three-dimensional form were out of the question. As other students crunched and mashed the foil into figures, animals, and structures, Kim methodically laid down strip after strip of tape, creating first a background and then a figure to be placed in low relief atop the background. The Divine Character is an accordion-pleated creature who rose only slightly off the page, like a primordial being rousing itself from sleep (figure 12). The creature asked to be embellished with patterns of gold and green glitter paint, and Kim complied. It came to resemble an Australian aboriginal painting of the Dreamtime. Kim dialogued easily with her images, and they had lots to say to her. Her intention the day the Divine Character emerged was: To be playful with the foil. To be willing to allow whatever happens, to happen. Let my imagination be outrageous.” In part her witness reads: “I’ve enjoyed laying down the tape. I feel I’m soothing the creature taking care of rips mending and healing the creature as I tape.

Figure 12. Divine Creature, by Kim Conner. Tape and foil.

KIM: Now that I’m really looking you over, who are you?

CREATURE: I’m a Divine Character from the supernatural world . . . I’m god-like with links to the ancestral world. I’ve come into being so my spiritual identity can be expressed through your creativity.

KIM: Then I wonder if you should be painted swamp green?

CREATURE: Gold would transform me and I could express the spiritual inner nature.

KIM: What about the beauty spots?

CREATURE: Oh! Keep them. They are the radiance of my soul.

As Kim continues to work on her tape-and-foil sculpture, her intention continues to evolve. She writes: I intend to continue to experience my Divine Character and the transformation happening. To continue our conversations in transforming our experience together. In her witness, she writes: I’m allowing the Divine love to enfold me, move through me and express who I am. From that growing feeling of love, I began to experience strength, power, and security. This is about transformation of my self. The feeling of love began to grow into a sense of love and compassion for myself.

It was in the act of making the design on the Divine Creature that Kim began to feel her own empowerment growing. The strength and beauty of the crosshatched patterns evoked ancestral power for Kim, as well as security. It was as if she were making symbolic marks that literally linked her with past patterns of spiritual identity that had become frayed and worn through time and neglect. The creature reminds Kim that compassion for herself is a crucial element of the transformation taking place. The simple act of paying attention through making marks is experienced as soothing and healing.

As Kim completed work on the Divine Creature, she made the following intention: I want to experience that spiritual presence within me to flow into those areas I hold limiting. For my limitations to be transformed into new patterns. For these new patterns to express themselves onto my Divine Character my figure from the outer world but of the inner world. The word want creeps into the intention, which will always evoke the state of lack. Often when we make big intentional leaps as Kim does here, the process reminds us that there are steps to transformation and we are wise to invite divine energy to enter our lives with some gentleness, allowing ourselves time to integrate our new learning. Kim’s love affair with her soul is next expressed in another creature that did begin to gently reveal areas where Kim limits herself.

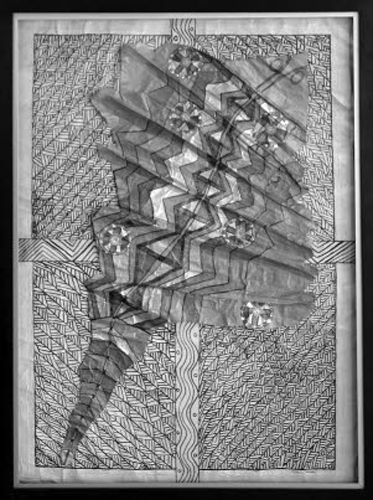

Most of the messages were about the divine spark within her that she had lost sight of. Her images, in a blaze of glitter paint, were eagerly reflecting that divineness back to her disbelieving eyes. Kim is not a flamboyant person. She tends to choose her clothes from the conservative side of the L. L. Bean catalogue and walks with the physical assurance of the championship skier and tomboy she was as a girl and teenager. Her tape-and-foil bird (figure 13) reminded her that underneath that sensible exterior beats the juicy heart of a wild woman. Her witness to her bird, her second Divine Creature, says: I do like the head and face. The eyes are friendly, goofy, and lovable. The tongue long and curvy so it can catch what it needs. I made the body folded back and forth like the past creature thinking this one would walk, unlike the others. But now I don’t know because I hear whispers saying I don’t need legs, don’t you get it? I can fly. How?

Figure 13. Bird, by Kim Conner. Tape, foil, feathers.

KIM: I really don’t get it. Now is the time to have a conversation spiritual creature, you don’t have to whisper, just put it forth. What would you like to say?

CREATURE: Okay, okay. I will talk. I had to whisper before because I had no way to express myself but the long tongue will do, so listen up. I don’t want legs. I’m not about walking. It takes too long. My folds will flap so I can get where I need to go, but you’re not finished with me. My body is long and I need feathers, bright, colorful feathers so people will notice me and see my beauty. Do these things for me and we will have more conversations.

As Kim continued to work on the bird she made the intention: To be open to whatever developments come and to connect with the sacred part of me from which I receive soul wisdom. Her witness reads: I confess I do like you my spiritual bird. Hard for me to believe you came from my deep inner soul. How pink, cheerful, fun and charming you are! I knew you existed but I can’t pinpoint where you are from. How alive you are! The bird replies: I’m glad you called for me. I’ve been waiting for you to lighten up your soul—take it easy. Makes it easier for me to fly out from beneath all that heaviness you have insisted on going through. I say just toss it aside. Move it all out so I have more room to be. Then we can be one with the spirit.

Recently Kim celebrated her fiftieth birthday with a ritual created especially for her by Annette, another studio artist. To prepare for this event, Kim went back and reviewed her life in five segments, one for each decade. Each of five women friends stood at a point around a circle of candles set on the floor. At each spot Kim spoke of life events and honored especially important people who had loved and sustained her in that time period. In her earliest years, it was her grandmother. For a period of time it was her father, who taught her to ski and entered her in her first race, which she won. At several points there were teachers who encouraged and supported her artmaking when there was little else that interested her in school.

As Kim shared the most recent five or so years of her life, I learned that the year prior to taking the studio process class for the first time, she developed a mysterious condition in which her right side became unaccountably numb. Kim is a preschool teacher and the mother of two active boys ages ten and twelve. Her husband, Bill, is a theatre designer who travels frequently. Kim has always managed the household. Every aspect of her life demanded that she work hard to sustain others. With nothing to replenish herself, Kim’s soul had slowly begun to starve. She had even taken on an additional volunteer responsibility at a hospice program, helping grieving children make art projects. The Creative Source often guides us into situations to work with others who can mirror back to us some essential aspect of our own being that has become lost.

Kim’s numbness became acute during a time when her husband and sons were all away. In solitude her body mutely cried out to her. A friend accompanied her to the emergency room for tests that revealed nothing. Kim’s numbness was soul deep and not visible on an X-ray. One day two friends dropped off a bag of art supplies, a stroke of divine intuition. Kim says she had forgotten she had ever even made art. Once a printmaker and stained-glass artist, she had given all that up because of safety concerns when her first son was born. Another friend, the one who recommended my class, recalls thinking it odd that when their children played together at Kim’s, the activity was never art. There wasn’t a crayon or a paintbrush to be found in Kim’s home. The first images she created with her gift of markers and paper was a series of suns, a motif that continues in her artwork today. At some point these drawings were not enough to satisfy Kim, and she longed to be able to share her reawakening creative self with others.

Once the creative energy began again to flow and spiritually warm her, Kim’s art took off. There are goddess figures, spirals, and flying beings in her work. Over the past few years, she has created a series of mandalas to deepen and celebrate her renewed wholeness. The mandalas are rich and colorful celebrations of beauty and grace. An especially poignant one is dedicated to her grandmother, who loved Kim boundlessly and mirrored her divine spark back to her in her early years. Everyone who sees these mixed-media collages senses the divine energy that is held in their designs.

When we begin to wake from an emotionally frozen state, whether induced by the restrictions of our chosen roles or from some sort of trauma, we develop new creative edges that want to grow forward. Friends and family members join in the challenge of coming to appreciate the new person unfolding before their eyes. Changes can occur in relationships with others when our creative spark is kindled. Kim’s creativity had never disappeared altogether, of course. Much of it had been channeled into her work as a preschool teacher. As Kim began to nurture her own art process, a coworker complained that her teaching had become less creative—an untrue and wounding remark, especially for a conscientious person like Kim. In most cases, those closest to us benefit from our increased presence as fully alive beings. Kim’s young sons have spent many happy hours making art with their mom around the dining room table. As Kim lives more fully as an engaged artist in the community, she instructs her boys in many subtle ways. She provides mandala artmaking classes in the teen program at her church, where her students see her as a wise and compassionate teacher. Through sharing artmaking Kim is open to their spiritual questions in a unique way. When the family renovated their second floor, Kim’s husband lovingly redid a room expressly for studio space.

For many of us who have been loved imperfectly and inconsistently in our lives, the divine energy of the Creative Source can seem like the sun, hiding behind clouds more often than shining and helping us to shine. Kim’s choice in her birthday ritual to focus on each person who has embodied the sun in her life, to remember her grandmother’s love through the rose mandala series, creates her special spiritual path through art. It is no accident that the sun began her journey to wholeness and continues to be a predominant totem in many of her works. Her connection to the Divine through artmaking enables Kim to be a conduit for powerful, nurturing sun energy in the lives of all who know her.

Kate in the Artist’s Garden: Sallie’s Story

Sallie’s involvement in the studio practice coincided with her oldest son graduating from high school and leaving home for college. That same spring she graduated from art school herself, a process that Sallie had spread out over a number of years to accommodate her responsibilities as a wife and mother of two sons. The studio both filled the void left by finishing her formal art education, providing a group of artists to relate to, and afforded a transitional space to explore the new self that was emerging as she began to claim an artist identity. Sallie describes herself as living a “dual existence.” Every summer she returns to her family’s rustic New Hampshire home, the touchstone of her early life. Although her family moved often when Sallie was young, the house in New Hampshire was a constant presence, remaining unchanged since she was seven years old. New Hampshire represents the “happiest parts of a happy childhood” in which Sallie spent all her time exploring nature, reading, sketching, and imagining life as a Native American as she searched for arrowheads in the woods. As an adult, she continues to return every summer and, admittedly with a bit of guilt, forgets her own family as she sheds her roles as wife and mother and rejoins her family of origin in the one-hundred-year-old wood-frame house that holds their collective history.

Sallie characterizes the two selves that she inhabits as the eternal tomboy and the dutiful good girl. She remembers puberty as being “traumatic.” She couldn’t continue life as a tomboy and, at that stage, life identities were clearly divided up along gender lines. “Boys had all the things I wanted,” she says—like freedom to explore, play sports, and not take care of others. All the interesting female possibilities seemed to fall to “bad girls,” and Sallie, daughter of a minister, was not one of those. The studio process became the liminal space where the tomboy and the good girl could meet and begin to dance together and create new possibilities. Her intention for the first day is: I want to let go . . . I want to go deep down inside. I want to touch my feelings. I’m thinking I cover up the dark stuff . . . Look for the pleasure. Do I ever let myself look for Pleasure? I am apprehensive—afraid—of this class, but I am here. My intention for this first day is to find the pleasure in making marks. My intention is to discover what I really feel.

I always encourage artists to notice their use of the word want. To want is to not have. The Creative Source will give us what we ask for, but not what we “want.” Sallie writes more than a few words to explore and finally get to her true intention: to find pleasure and to discover what she really feels. Her first experience is the drawing workshop where we move from a small piece of paper and one color of oil pastel to a large piece of paper taped to the wall and whatever colors we choose. Drumming music is playing during our drawing time. Drawing this way is a means to make a path into the Creative Source quickly and to reduce our resistance by making it harder to think, harder to judge, easier to enter our body wisdom through the loud percussive beat, through standing up and simply “making marks,” not “drawing.” Sallie’s witness reads:

This drawing tells a story. I know because I wrote it on the drawing. There’s a tipi in a wood and there are tall, icy peaks—mountains in the background. The sky, what you see of it, is dark and threatening. There is snow on the ground and it is near sunset—the snow is lit with red. But the red is also blood. My menstrual blood and the blood of the massacred Indians and the blood of my shattered dreams. There are plants—strange, ghostly plants growing up out of the water in the foreground. And a reflection of the moon or sun? A black cauldron maybe. A bank of bloody sunset snow. There is a border around this drawing that takes the shape of the paper, but it is broken into and out of—it contains, but it does not confine or hold everything within. And there are mountains in the border, at the bottom and the ghost-roots of the plants. There is a little red child in (on?) the tipi. There is a half-opened door to the tipi. Come in Lone Wolf. Am I the Lone Wolf? There are paths and a huge red forked tongue. Am I lying? Are you lying to me, picture?

Sallie continues in her witness to notice what felt good to her, to thoroughly describe her use of colors, to note her judgments of herself and others. She notices that she could have continued making marks for longer than the allotted time. Then she checks back in with her intention: Did I make any move toward my intention? Do I know what I really feel? I know I love red and black and white and brown. I like my white tipi. I like those black mountains with the red outlines at the bottom of the border. I like movement—dancing while I’m drawing. And I like stories. And I like to say I’m afraid when I’m afraid and I don’t have to act on that fear. Can’t I just feel it and let it come with me? I think it’s inherent in who I am and I can live with it. I don’t want to have to explain it or give it up.

By describing her drawing so thoroughly, Sallie extends the time she spends looking, seeing, and feeling her experience. When we stay with our experience we come to truth. Artmaking allows us to stay with feelings—fear, for example—without turning away or getting too busy to notice. We are moving when we draw, so our feelings do not clot in our bodies but are more likely to move through us and out rather than freezing our muscles and building tension that results in constriction over time. Even though Sallie could have continued making marks, stopping is also part of the process. We stop before we are completely fatigued or overwhelmed, but not so soon that we stay entirely on the surface. Sallie has sketched out the contours of who she is in this complex, rich, and metaphorical layering of marks on paper.

I originally got to know Sallie when I joined a writer’s group while working on my first book. We gathered around Sallie’s dining room table in her cozy and cluttered house. She first learned about the studio process by listening to me struggle to articulate it in my writing. I was surprised when she chose to partake of the process; for on the surface she seemed to have her creative life well in hand and to be a bit reserved and skeptical of things bordering on “spiritual” or “therapeutic.” The walls of her home are filled with watercolor landscapes of her New Hampshire experiences done on fine Arches paper and tastefully framed. Like Kim, Sallie had some classical views of art and art materials; but in addition to making more traditional artworks, she also collects lots of junk and makes found-object collages.

Sallie arrives at the studio in spite of the fact that graduation preparations for her son and visiting relatives are claiming most of her time and energy. She writes: There are six hundred reasons why I should not be here today, but there are one or two reasons why I should and I am acting on them. In her first painting, Sallie owns up to her dislike and disdain of the tempera paints. With the intention to focus, she chose colors she hates—bright pink and teal—and with gusto paints hearts and tears, symbols she considers “anathema.” Still, she grasps a basic tenet of studio work, which is to accept yourself in the moment, negative feelings and all—in fact, to amplify them in order to really get to know them. She incorporates words into her painting that she had glimpsed on a tow truck on her way to the studio: “twenty-four hour heavy duty.”

I painted it in two or three times, in at least three colors—and it keeps getting buried. Obscured. There are red tears falling down the side of the painting but they are apples and pears by the time they reach the bottom . . . a naked woman is trying to sneak in the side I’m starting to self censor this witness. I see things here I’m not willing to tell. Or am I dying to tell all? How bare can we get? There’s a naked woman trying to sneak into this picture. I’m going to paint her clearly, let her in. . . . I’m a mom about to lose her first-born. . . . but I’m not everybody’s mom and I don’t have to be perfect and I don’t have to do everything and I can be that silly, ugly, big-chinned warrior child and I can be that weeping Madonna who can’t get her act together enough to get herself into the picture, but I don’t have to be the twenty-four hour heavy duty lady. And Lou may be rising up and growing away from me, but he is crowned by my watchful eye and pierced by my watchful eye and he is eating my tears which are turning to apples and pears . . . he’s a snake, ancient symbol of wisdom. He’s got colored scales to protect him and green daggers up and down his back. He’ll be just fine . . . Even I will be just fine even if I never did get centered and focused today.

Sallie reinterpreted the personal symbol of “the watchful eye” that feels responsible not only for her own son, about to slither like a snake off into his own life, but for all young people. Almost always when we sit with our strong concerns, especially those that seem a bit inflated, like Sallie’s for endangered teens or Kim’s for young children who have lost a parent, we find our way to a disconnected part of our self. The more we learn about the self pieces of the puzzle, the more genuine and useful our work on behalf of others can become. By giving herself permission to be contrary, Sallie opened a door to those things that don’t fit with her conscious self-image. It was her first step, though not altogether a conscious one, in letting the “bad girl” out. Like many first paintings by those who are ripe for a change, Sallie’s contained the code for all that had been kept hidden and needed to be unpacked. Her use of color and brush strokes bears witness to the energy that can be released once an artist moves through their barriers to tapping the Creative Source.

In the next several sessions Sallie worked on letting go of “being mother to the world.” Her intention is: To touch my insides. Find the magic places celebrate the day and the beginning of summer. To say with all openness, “Here I am Lord.” To answer calls from within. My intention is to have fun. Any questions? Any issues? How do I go about becoming an artist? It’s too late to become an artist. The question is, what does the artist within me want to create and want to explore . . . What do you do when you are displaced, I will explore this split in my life today. My intention is to explore New Hampshire and Chicago and what I feel about this split.

Sallie’s subsequent work in tape and foil (figure 14) yielded exquisite and instructive images of two parts of herself. The first image is Luna Moth. Sallie lovingly created this creature with fine detail. Crafted out of aluminum foil and masking tape, the Luna Moth has two sets of wings. One set of wings represents her New Hampshire life; the other symbolizes Oak Park and her present family. After describing the image in her witness, Sallie began a dialogue: Talk to me, Luna Moth you are a two-sided creature.

Figure 14. Luna Moth/Dancing Girl, by Sallie Wolf. Tape, foil, found stuff.

LUNA: I come out of your past—kindergarten, you hatched me then.

SALLIE: I wanted you. The teacher let you go. I couldn’t believe she let you go and yet I know it was selfish to want to kill you and keep you all to myself, spread flat in a cigar box maybe, on a bed of cotton.

LUNA: I came back to you.

SALLIE: Going to New Hampshire last week surprised me. How beautiful it was. How much I loved the smells, the sounds, the feel of the air. I didn’t need anything else. And then I found you squished on the road it was a gift from my past. Was I a child again in New Hampshire? Just me and my mommy. No kids. No husband . . . Your Oak Park wings are bigger.

LUNA: But not as firmly attached.

SALLIE: I could fix that next week. I think I want to make my moth a girl with two feet to stand on and five arms to try and do everything at once.

LUNA: Balancing will be the trick . . .

SALLIE: The metaphor is always the butterfly hatching out of the cocoon. I’m waiting for a girl to hatch out of the moth!

LUNA: Where is the woman?

SALLIE: She’s in there, I guess. Woman Moth Woman Moth . . . Moth—just slightly more than half the word Mother. . .

The next part of Sallie to emerge is what she first calls the “Me-doll” skinny, like I was as a kid, but with boobs—I thought of them as Big Boobs but they’re not, especially after I bound them with tape and foil, nearly strangling myself to make a neck to hold my head. No face yet. I’m thinking big red nipples—maybe brown. Real pubic hair. This moth and this doll are holding each other up . . . The Oak Park wings may be bigger but the New Hampshire wings are stronger. But I am outside the moth but I need the moth to help stand, to help me dance. I’m dancing with the Moon Goddess. I’m dancing with the Luna Moth . . . no faces yet. No features. We’re still emerging, this moth, no this goddess and I.

In a subsequent session, Sallie continues to work on the dancing girl. Her witness reads in part: The most fun I’ve had here I think is dressing my doll. A black patch of pubic hair. Red glass bead nipples. Wild gray hair. A scarf like I’d never wear. Leggings in blue silk, what a fashion plate. She had been bent, to ride the moth, weighing it . . . Where do these images come from? That doll is me—a climber, hanging by my knees, half-naked—a free-spirited child. That’s who I once was—someone I miss right now. I don’t like the prudish, worry-wart person I’m becoming, always disapproving of this, that and the other thing . . . I don’t know how I’ve become so judgmental except I’m always in reaction against something. Against cars and drivers, porn on T.V. and tooth whiteners (try gesso) and ads for vaginal lubricants and English sparrows and perfectly manicured lawns and lawn care services and mobile phones and Wisk and junk mail and Venture and sales on Thanksgiving Day. I want to be that climbing, half-naked child/woman again, dancing with the moths in the moonlight (and mosquitoes?).

With Dancing Girl holding the reins, Luna Moth has a chance to fly in some new directions. Sallie winced at that summary of her images when she read the manuscript; and maybe it feels a little too glib or corny. Images don’t promise a simple, happy ending. Dancing Girl, like my Dark Boy in the next story, carries edited parts of the self that throw up red flags. Dancing girls, after all, abound; but they are usually dancing for an audience of paying customers in a strip club. Sallie’s girl dances for the sheer joy of moving her body.

Our culture offers little room for mature women beyond the mother role. Once reunited with Dancing Girl, the artist is born or reborn. Through Dancing Girl, Sallie reclaimed her sense of humor and recovered the path to the place of nonjudgment and physical engagement with the natural world that her tomboy self knows so well. It was clear that Dancing Girl didn’t need Sallie’s overserious vigilance and protection. As time went on, Sallie created a series of moths and dancing girls. As she continued to let her mother role recede, she also got into exercise and weightlifting and returned to that pre-wife-and-mother place to find the vitality and spark to reinvest into her creative life. I’m not sure if she is dancing yet.

Sallie is also a writer and has published a children’s picture book. She has had a story incubating inside her for years that seemed more complex, perhaps a novel or a work of young adult fiction. She decided to use the studio process and make an intention to find the story through the art. Artists commonly sabotage themselves by becoming mired in internal arguments about whether they are a painter or a writer, a visual artist or a word artist. Sallie’s solution was to employ the art to excavate the story. It took several years for Sallie to trust the process enough to really use it. She says she wanted it to work “behind [her] back” because the possibility of getting what you ask for is “too direct, even feels selfish and unmindful of others.” As Sallie discussed her fear and reticence to use intention directly, she realized how her deeply ingrained Christian upbringing affects her as an artist. Predicated on a sense of scarcity of resources, the worldview she grew up with taught her that getting what she wants might mean that someone else has to do without. Sallie decided to explore these issues through the story that she had been carrying around inside herself—the story of a young girl named Kate and her encounters with an older woman artist. Sallie’s intention, to discover the story through the art, leads her to the disowned “bad girl” part of herself. The group nature of the studio was ideal for Sallie to explore the bad girl. She could eat more than her share of the cookies set out for snack breaks, not help the new artists, use lots of materials, and work entirely in red if she chose. These symbolic acts of rebellion accomplished the goal of loosening the remnants of that constricting sense of being “mother to the world.” Though powerful enough to manifest the intention to know the bad girl and actually let her out, these gestures remain harmless to others.

As time went on, Sallie refined her intention to include letting the bad girl out in the garden, receiving whatever comes and letting the story emerge through the pictures. Sallie worked on images that had until then existed only in her imagination: the house in which the artist lived and her garden, where much of the early action in the story takes place. As the story began to arrive through Sallie’s witness writings, she read them aloud and many of us in the studio began to feel we were hearing installments of a lively book. Sallie found it uncanny how things just came. Soon we knew that Kate was an eleven-year-old staying with an unmarried aunt while her parents were away doing research in another country. We peered over Kate’s shoulder as she snuck into the artist’s backyard to explore. We listened in as Kate and her friends at school speculated that the artist might be a witch because she lives alone with cats and has wild white hair.

Sallie began to enjoy the magic of putting down her bucket and pulling up story fragments from the well of all possibility. The process gave her the power of not having to be in control. The paradox of giving up control and receiving power in return astonished Sallie. When we step into alignment with the Creative Source, we experience an enchanted state of effortlessness. As other studio members became invested in her characters and story, Sallie met her old challenge: fear of not meeting the expectations of others. The bad girl had emerged in Kate, but Sallie’s dutiful alter ego was still close by.

Recently Sallie received an artist’s grant to work on another project. For over eight years she has looked at the moon. She creates charts and graphs of her observations. She notes when she looks and when she forgets to look. The Moon Project is a vehicle of awareness for Sallie. It provides a kind of discipline in that she must accommodate the moon’s schedule to accomplish her aim. The paradox is that in noticing the moments not seen, she becomes more aware of the opportunities around her. The project is simple and elegant and began because one day Sallie noticed the crescent moon in the east and didn’t know what to make of the moon rising in the morning. She realized then that her suburban life in Oak Park was relatively disconnected from nature and that she was hungry for a closer relationship to the natural world. This, she felt, would help her to locate and touch her own inner wisdom. She became, in her own words, a “preliterate person,” discovering the moon and its cycles firsthand. She was excited to be teaching herself. The “watchful eye” that appeared in her early studio painting became a device to chart the location of the moon in relation to the perceived horizon.

Unlike the New Hampshire countryside, the flat Midwestern landscape and densely built-up grid of houses surrounding her Oak Park home made Sallie work to see the moon. This work takes her to a place where she is aware of her smallness in the grand scheme of life, and it reminds her of a different relationship to time. Sallie noted that in the artist’s residency that her grant provided, where her intention was to work on the Moon Project, it took her six days to slow down and feel her way into the work. She notes that her powers of observation have grown through looking at the moon: “no matter what one looks at intently, when you draw the world, you see the world more.”

Early in making the Dancing Girl, Sallie noted in a witness that the moon charts would make a great backdrop for dancing girl. As the artist in Sallie comes more to the forefront of her life, and honors each element of her being, she is able to combine the discipline of the moon charts, the adventure and playfulness of the dancing girl, and the ancient wisdom and nurturing order of Luna Moth to bring forth Kate in the Garden as a fully realized work of fiction. Like many artists who have engaged deeply with the studio process, Sallie has incorporated intention into her life beyond the studio as well. “It gives you a starting place,” she says, “regardless of what you are doing.”

The Indigenous Soul: Pat’s Story

The way teachings come to me is messy and circuitous. When I thought about how to write about some examples of teachings that come through artmaking, I realized that it is harder than it looks. Themes and ideas thread their way through many images over days, weeks, and years. The place of all possibility, from which images come, is not governed by linear time. I have had unfinished images complete themselves through a chance encounter, as if a stranger had handed me a puzzle piece I wasn’t even consciously looking for. Whether we realize it or not, all image makers are part of a vast collective web. We collect and absorb patterns, colors, and stories on a deep level. Also, those artists who develop their sensitivity are like receptors for the images that the culture needs to have expressed.

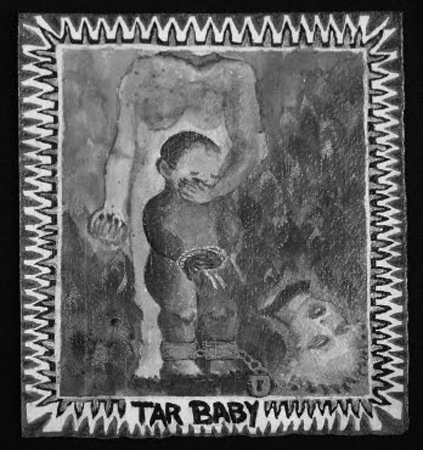

Working in the studio, we are immersed in each other’s images. We reference each other, incorporating pieces of what moves us or completes us into our work. In this way we sew ourselves together in communion. To emphasize the overlapping quality of art as a spiritual path, I have woven my own images around and through the stories of other studio artists in this book. One day, I was receiving some energy work from a woman trained in Chinese medicine and a form of bioenergetics. While reading my fields, she mentioned that the energy seemed “sticky” and something about a shy child part that needed encouragement to express herself. Under other circumstances, I might well have rolled my eyes and thought, “Give me a break, the ‘inner child’?” But as she spoke, perhaps triggered by her use of the unusual word “sticky,” an image that I painted over ten years ago, entitled Tar Baby (figure 15), flashed in my mind like a slide on an inner screen. The arrival of the image in my mind confirmed for me that Danuta’s perception had merit. She did some clearing work, noting that there was sadness and grief associated with the child. After awhile she saw the child dancing. Once again an image flashed in my mind, this time one I had recently painted of a dark boy dancing on one foot, emerging from a cave or a hut, accompanied by a white bird. I described the two images to Danuta, who looked startled. “You’re a prophet of your own transformation,” she said. I couldn’t wait to return to the studio to look at both images. I knew where the painting of Tar Baby was stored, but I didn’t expect to find my witness writing easily. I opened a notebook that corresponded roughly to the time I remembered having created the image, and the witness to it was on the first page. At the time I painted Tar Baby, the full meaning of the image eluded me. The image shows a small dark boy, his hands bound, his feet shackled, his eyes closed. He stands in front of a blue-gray woman, whose sharp, red-tipped fingernails grind into her palm, drawing blood. Her severed head lies on the ground. Fire rages behind her. In the witness, I ask, Who is this headless woman?

Figure 15. Tar Baby, by Pat B. Allen. Watercolor.

HEAD: As you can see, there was no room on the page for me so I went tumbling down.

ME: Who decapitated you?

HEAD: No one, I just fell off. There wasn’t room for all those pesky thoughts . . .—Anyway, we had to shut up that stupid baby.

ME: Why?

HEAD: He wanted to say things and cry out loud about them, he’s really a nuisance.

ME: Wait, his hands are tied, he’s naked, his feet are shackled and you have your hand over his mouth!

HEAD: Me? Oh, I do? Are those my hands? I don’t think so, I have a headache, my nails are digging into my hand so I don’t feel the pain in my neck. That’s it, I told you, he’s a pain in the neck. If I could just get him to behave! He’s bad, a bad child.

ME: But he looks really sad and gentle to me.

HEAD: Looks? Looks? I can’t see anything; my eyes are closed. Chicken with my head cut off, that’s me.

ME: Tar baby can you speak? No? Then can you send me your thoughts?

TAR BABY: I have to stay near to her and try to keep very still. If I’m still I know the fire will die down. I made her head fall off because I was too loud. I can keep quiet if she helps me. We can both be very quiet. No one will make a peep and then it will all be okay. My hands hurt and my feet do too. I’m very cold but I’m here and we’re together that’s what matters.

I ask the lock on the shackles to speak.

LOCK: I’m for safety; I’m a safety device . . .

Ties that bind, blind

They don’t mind

Small price to pay

To get to stay

Together forever

In hell . .

Poor tar baby and beheaded mom! Framed by dungeon spikes, a family snapshot, sticky, sticky, stick together.

Open your eyes

Listen to cries, sighs,

Challenge the lies

Rise, arise

Hell is a construction, collusion, collision

Of needs, greeds

Growth of emotional weeds

Even the flames in this hell are frozen.

Open your eyes. Feel the cold, touch the sticky, black tar baby

Tears are his solve vent (solvent)

Cry your tears over him, welcome him back

His love is so great he’d die for you

ME: What can shift you two? Is there something I can offer?

HEAD AND TAR BABY: Honor us, see us, hear us, don’t fear us.

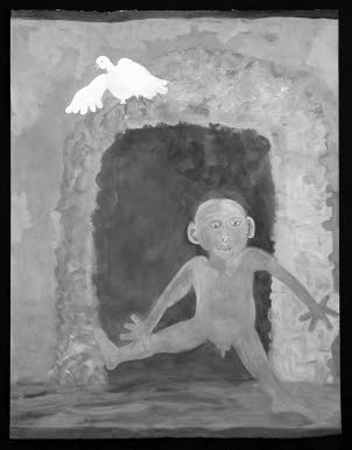

Figure 16. Indigenous Soul, by Pat B. Allen. Tempera.

Next I looked at the witness writings to the new painting of the dark boy emerging from the cave (figure 16). My intention for the painting was Today I welcome the artist and engage with her. I imagined painting a figure of a woman stepping out of a hut or a dark space into light. As usual, the image has ideas of its own. The character that appears is more a child in proportions. As I work on the painting another day, my intention is to understand more about creative work. I ask: Who is the writer? Who monitors and manages the creative process internally for me? Who makes it safe and right to create? I ask to engage again with this being, the artist, the writer. The character seems to be a boy, and in the witness dialogue he asks me, Who were you when you were just a boy?

ME: I don’t understand the question.

BOY: Yes, you do.

ME: I guess I don’t understand.

BOY: Active, industrious, maker of things, when you were that . . .

ME: When I was maybe eight or ten I made a fence once in the backyard, it was ramshackle and I painted it. My family was horrified; they thought it looked trashy. I turned over rocks and looked for bugs. I collected rocks and burrowed under piles of leaves . . .

BOY: The boy who doesn’t please his mother runs away from home.

ME: But I was a girl, I protest.

BOY: Don’t be so literal, please. You were he-she-he-she as all children are until some circuits are cut and you forget how to play certain ways or to run or to cry.

ME: This is confusing.

BOY: No it’s not. Your soul is its own best friend, a bifurcated being, Hansel and Gretel, Raggedy Ann and Andy, until it comes together.

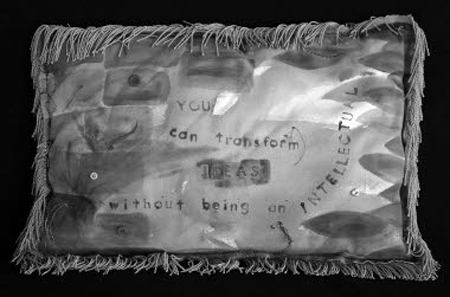

I am also working on a pillow at this time (figure 17). I come to the studio in the low-grade sense of wonder that I live in a lot of the time—neither freaking out about something nor ecstatic. Then studio is a refuge, a respite from headlines and news stories. It is a place to get guidance on how to act. Does it tune me to a frequency of peace so I simply don’t cause as much conflict in the world? The pillow says, Comfort can be taken in rough edges, surfaces need not be slick to be beautiful. I have stamped some words on the pillow from another witness: Nothing is exactly any more. I love this aesthetic of messy edges. I love the idea of boundaries bleeding into one another. The precision of sewing real garments never thrilled me this way. The pillow says: Comfort can come with ragged edges. You can give up thinking things must be tucked in and neat. Fall in love with the ragged, the imprecise, have you ever noticed that in nature the perfection is that abundant room is made for the imperfect? Love and honor that in the world and in people. Let everyone off the hook and put your head down on the pillow of imperfection and rest.

I enjoy having a messy pillow arrive and reinterpret women’s work. This reclaiming of all things rejected: sewing, offering comfort, making items for use in the world that don’t look the way I expect. Doing all this with a different aesthetic, a new agenda that reclaims simple means and thumbs its nose at a clean sleek interpretation of beauty. The witness says: Fuck you sleek, shining wrinkleless beauty, welcome stains and edges showing. I write: I feel a manifesto coming on, an articulated aesthetic of the poor, tired, and crumbling yearning to be set free and danced into new forms.

Figure 17. Pillow, by Pat B. Allen. Canvas, paint.

I return to the painting of the dark boy / artist / writer. The idea “indigenous person” comes into my mind. How to locate the indigenous person in the soul? The definition of indigenous is “having originated in and being produced, growing, living, or occurring naturally in a particular region or environment.” A dark boy is indigenous to the region of my soul. This word is very close to indigent. To be indigent is to “live in a level of poverty where real hardship and deprivation are suffered and the comforts of life are wholly absent.” Indigent/indigenous. Often indigenous people end up indigent when colonizing forces move in.

BOY: You impoverish and don’t nourish what is native to your soul.

ME: Me?

BOY: All of you in the human realm. There are parts you separate and starve. You can’t redeem one without the other. The mother who is unfree restricts and deforms her child.

Roundabout, rhythmical story and play are how studio teachings emerge. Is it important to say anything more? When these words are spoken and images witnessed in a group, without explanation or attempts to decode them, do they create change in us below the level of cognition? I think so. Part of the work seems to wander back to a place of knowing that came before books and theories in lines of type marching over a page colonized our brains. Sometimes when I sit on an airplane and every passenger’s nose is buried in a book, I just look out the window and imagine myself jumping down into the sumptuous softness of the clouds. How quickly awe wears off! When we read our witness writings to each other in the studio, I often feel that we are sitting around a campfire and telling our dreams, pulling out of ourselves a deeper truth than the beginning, middle, and end that can be committed to straight lines of prose.