At some point all of us need to engage intellectually and emotionally with either the spiritual and religious traditions we were born into or alternatives we have been drawn to as adults. This need is both personal and transpersonal. “There seems to exist a correspondence, which is not necessarily causal, between transitions in cosmic planetary cycles and changes in the religious and cultural symbols that appear on earth during various times” (George 1992, 64). The appearance of feminine symbols in spiritual discourse may be a need not only of individual women seeking a more resonant face for God, but of the planet itself. We might imagine, as scientist James Lovelock does, that the planet is a living being, whom he has called Gaia. Perhaps She wants to show Herself to us in new ways because the planet itself has reached a point in Her cycle where that is necessary.

There is a legend in Jewish tradition that the feminine aspect of God, the Shekhinah, argued with God when he banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. The Shekinah went into exile with her children (Patai, 1990, 158). Our job, some mystics teach, is to restore Shekhinah to God through acts of compassion and justice. While for generations the feminine aspect of Judaism has been somewhat dormant, now, not only in the egalitarian Jewish Renewal movement but even in Conservative and Orthodox worlds, feminine energy is seeking expression.

The way that religious symbols change is through our interactions with them. Symbols such as the cross in Christianity and the various deities in Hinduism change according to the way artists and people of faith depict them, compose prayers to them, and construct their places of worship. While there may be people who are born into a faith and culture that fit them exactly and allow them to grow and develop fully, many others seek out different paths. Important breakthroughs are often made and new definitions created when people from outside a faith tradition bring new eyes and ears to its texts and rituals. Saint Paul was a Jew named Saul of Tarsus who, although he never met Jesus, became the founder of Christianity as a religious system. “Paul’s meditations on the significance of the Christ became the basis of Western understandings of Jesus’ purpose, at least as much as the disciples did” (Segal 1990, xi). Martin Luther, frustrated with corruption in the Roman Catholic Church, founded Protestantism.

In contemporary times, boundaries between faiths are sometimes more permeable, admitting and incorporating customs of other groups. The insight meditation teacher Sylvia Boorstein and many others have sojourned in Buddhism and brought meditation and other practices back to enrich the Judaism of their families of origin. This is another manifestation of balancing energies, both personal and collective, of the innate drive to unfold and move toward wholeness. Image making is a valuable way to explore and integrate the received truths of any system and sift through what attracts us and has meaning without swallowing whole or being swallowed whole by another belief system. The Creative Source longs for Its stories to be told and retold, embellished and rejuvenated.

As manifestations of collective energy, archetypal symbols belong to all of us as the legacy of human creativity. Mindfully traveling through spiritual traditions via artmaking requires some sensitivity and a very clear intention. Mexican and Native American influences deeply inform the Judaism of Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb, whose congregation is in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her respectful use of Spanish language in services and incorporation of Native American values and customs in ritual grow naturally from her engagement in her landscape (1995).

When I am drawn to an icon or image from another tradition, I familiarize myself with its original context and subsequent interpretations in order to better understand its message for me. When Kali, a familiar visitor to my artwork, was joined by Kwan Yin a few years ago, I was surprised. I knew little about Kwan Yin, the Chinese Goddess of Compassion. The two figures had a conversation. I looked up some pictures of Kwan Yin to better portray her attributes after I noticed that she looked rather masculine in a small image I painted (figure 18).

On reading further, I learned that she had originally been a male figure, the Bodhisattva of Compassion named Avalokiteshvara; over time, the widespread devotion of women to Avalokiteshvara seems to have effected his metamorphosis into the female figure Kwan Yin (Boucher 1999). The writer Sandy Boucher says this about how aspects of spirituality enter a culture: “They come in through people—individuals who recognize a particularly compelling expression of our humanity in practice, a divine figure, a belief, a system, and make it real in their lives” (p. 5). We are all invited to become familiars with any manifestation of a divine force and to add what we learn to the rich story pool that animates human imagination. It is only through the devotional acts of humans that these deities begin to gain power in the human sphere. We dwell in the place of all possibility through our images and eventually learn what we’ve been called to learn. The artmaking process calls us to enter the place of no-judgment, where we are free to converse with Kali, Abraham, or the Golden Calf, for that matter.

Figure 18. Kwan Yin, by Pat B. Allen. Gouache.

Religious leaders may not be comfortable with the idea of retelling stories. It is interesting to learn how your faith group of origin approaches the idea of story. For example, the Catholicism of my youth didn’t spend much time with the “official” story of the New Testament. We did not read the gospels as students but instead focused on the catechism, a collection of precepts we were to memorize and recite, but certainly never question. Perhaps because learning through inquiry was forbidden in the religious environment of my youth, I was delighted as an adult to find my way to Judaism, in which questioning the story and retelling it—what Rabbi Arthur Waskow (1978) calls “Godwrestling”—is the highest expectation of Jews.

I am personally energized by the Jewish belief that one story will yield an infinite store of wisdom to anyone who intentionally engages with the text. This view invites exactly the sort of approach to imagery that the studio process offers us in a very concrete and hands-on way. However, even a tradition like Hinduism, whose stories are the same and the characters very well developed, allows for different interpretations of the physical appearance of Shiva, Lakshmi, and other deities. Building Bridges, a Catholic art organization that oversees the creation of contemporary icons, has added plaques with images of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Harvey Milk, Native American holy family groupings, and even an image of the Christ as a dark-skinned woman. I particularly love their image of the Catholic Mary, her Hebrew name—Miriam—emblazoned under the image of her holding a Christ figure that holds a Torah scroll. WeMoon, a women’s art collective, solicits women’s art every year for a calendar and note cards that celebrate the Divine Feminine as a wellspring of inexhaustible variation. Their work opens our eyes to the celebration of the Creative Source in everyday life. Images of the Divine that resemble us are deeply empowering. Otherwise, we are subtly led to equate all those who look like the picture of what our culture calls “God” with an inordinate amount of authority.

I had a powerful experience of “seeing God” one day at, of all places, a Six Flags Great America theme park. It was a steamy summer day and crowds of people were milling about the park. All of a sudden a small black boy, about two years old, realized he had become separated from his mother and began to wail. The instant I began to look around for either the mother or a staff member, an enormous black woman in a bright flower-print dress wheeled around and thundered, “What’s the matter, baby?” Standing slightly behind the child, I felt myself enveloped in a force field of energy that surrounded and protected that child and made a space in the crowd around him. Within seconds the woman had scooped up the child and was talking to him about finding his mother.

I was reeling from the impact of smacking into the woman’s energy field, which felt like pure, powerful love; all I could think was “She is what God looks like to me!” Sometime later I made the artwork in figure 19, which hung over the altar space in my Oak Park studio for four years. Surprisingly few people commented on it over the years. One day Fenson, a black teenage boy I worked with through our local alternative school, asked, “Who’s the black chick?” I answered: “She is my image of God.” He just solemnly nodded his head in assent.

Figure 19. What God Looks Like, by Pat B. Allen. Tempera, glitter.

The stories in this chapter demonstrate the possibility and power of new renderings of old spiritual stories and images. Annette’s story is the first in this chapter, followed by my story of Sabbath Bride, an image in which I explore the feminine face of God in Judaism. I invite you to reflect on your own religious background and current spiritual practice as you read this section. Notice whether questions come up for you. Is a personal, private spiritual practice enough? Is our engagement with images of the Divine a dodge around dealing with the pain of the world? How does artmaking lead to action or support action? These are questions that ebb and flow for me. Judaism teaches that our responsibility is twofold: tikkun haolam and tikkun ha-nefesh. We are called at once to heal and repair the world and to heal and repair our own soul. This is a restless edge for me that grows out of spiritual engagement. The Catholicism of my youth focused mostly on the afterlife. This emphasis, as Annette also learned, challenges one to suffer enough to become worthy of heaven. Two of my heroes are Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who wrote many important books and marched alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the civil rights movement. Traditions, like the images that support them, grow and change as a result of the actions of the faithful. Art gives us a constant opportunity to examine and renew our beliefs, elaborating and expanding the faith traditions and spiritual practices that sustain us.

Resting in the Embrace of the Dark Mother: Annette’s Story

When Annette first came to the studio, she never mentioned her early experiences with art or that her mother was an artist. Instead, from time to time, she would bring boxes of markers, paints, or other supplies as gifts to the studio. “They were lying around not being used,” she said, as she added them to the shelves for others to share. I got to know Annette first in her role as a shamanic healer. Friends mentioned her journeying sessions, her talent for traversing the veil between worlds, her work in soul-retrieval. A clinical social worker by profession, Annette found her way to shamanic training when she discovered Shaman’s Drum magazine and the work of Sandra Ingerman (1991). She experienced a soul-retrieval herself and found a community of others who understood travel to the spirit dimension. Annette had lived a secret shamanic life since childhood.

Annette led a “trance dance” session at the Open Studio Project, where a group of us danced blindfolded to drumming music and then drew and painted our experiences. For me, the dancing was such a profound experience of ecstatic embodiment that the painting activity seemed superfluous. I vividly remember the exhilaration of feeling completely at home in my body, with electrifying energy making me feel joyful and alive. I didn’t shower for days afterward to prolong the vivid sense of being fully flesh and bones. I wondered how Annette could bear being still during the trance dance. Our wearing blindfolds, which helped to inhibit judgments and self-consciousness, meant Annette had to watch out and make sure we didn’t crash into each other or the walls., In the painting I created afterward, I encountered the black dog that had been an early totem and guide of mine. He laughingly welcomed me to the realm of instinct and body. He reminded me that the ultimate aim of the creative process is to help us locate the joy and power of our physicality.

When Annette later signed up for a studio class I was surprised. Art seems a bit staid next to the power of shamanism and ecstatic dance. At a later time I experienced a soul-retrieval with Annette, and she once journeyed on my behalf to seek an answer from the spirits when it seemed my marriage was dissolving. The answer she brought gave me the faith to continue working for resolution of our problems. I mention all of this with Annette’s permission; I think one of the teachings the Creative Source is trying hard to convey right now is the mutuality we need to embrace in our quest for wholeness and healing. We are meant to pass the teacher’s staff from one person to another, to follow each other when we are in need, and not to become too wedded to our roles as teacher or student. Annette and I both grew up in the hierarchical Roman Catholic Church, where power flows in one direction only—from God to the Pope to the priest. The circular exchange of teaching in the studio shows us another way.

Annette became a regular presence at Studio Pardes during her work in the Creation Spirituality graduate program that was founded by Matthew Fox, a dissident Catholic priest. Fox views the creative process as sacred. In fact, Annette has incorporated collages of spiritual principles into her doctoral work, opening the wisdom of the images to others. The studio became a venue for Annette’s personal struggle with spirit versus matter. Her initial works were colorful and amorphous. Her witnesses spoke of dire Cassandra-like prophecies from the spirit realm. Instead of a dialogue between Annette and her image, her witness writings seemed like spirit voices aiming to instruct the masses. I had a strong sense that Annette’s intuitive gifts burdened her with an exaggerated sense of responsibility.

The beauty of the witness process is that because no comments are made, all words simply hang in the air while those of us in the room simply keep breathing. All words will speak to someone, and the speaker feels the energy or aridness of her words for herself without needing to be told. The eloquent and the learned eventually begin to realize that they are performing and let that acknowledgement enter the witness, too. It isn’t bad or good; it simply is. Annette might read a Cassandra-like piece about the doom of the planet as if she alone is responsible for this awful plight. After a short pause, someone else says, “I’ll read” and begins to describe a drawing of her child and how fearful she is of letting him go as he matures. The witness space shows us wholeness by giving equal time and weight to mundane observations as to brilliant metaphysical insights. We are reminded that our task is to keep breathing through both, and this balances us. As Annette spoke from the place of spiritual teacher, I found myself uncomfortable at times. As a person often given to making lofty speeches, as well as one frequently gifted with powerful information, I am especially grateful for her holding that seat and therefore that mirror for me.

After the attacks on September 11, 2001, Annette volunteered to create an art piece for our west-facing windows in the studio. Hundreds of cars drive by them daily, and we hoped to offer an image even to those who might not ever enter the studio. Through her collages, she conveyed the idea that the destruction of the World Trade Center towers was an act of transformation as well as destruction. Kali appeared in the second window with her sword of truth, presiding over the cataclysm. The final window is a golden web of images that made visible the insight that was fleeting for many, that this devastating act revealed the interconnectedness of all life.

Gradually, Annette’s work began to move into life issues and her personal story—the subtext that is always beneath our spiritual searching. At the age of four or five, Annette dreamed of swinging on the stars and moon in the night sky. She was painting rainbows across the darkness and calling out in exuberant ecstasy for others to notice the beauty and to rejoice with her. She recalls being filled with an intense joy and a longing to share it with others. She called and called, but no one answered her; no one joined her. In the dream, Annette quietly closed her box of paints. She dates the loss of her deepest connection to her own soul to this time.

Annette was born into a devoutly Catholic family that was poor and had a heritage of physical and mental illness. The mystical ecstasy of her earliest childhood became overshadowed by her family’s stern belief that suffering equals holiness. All the passion and wonder she had initially found in the natural world became transferred to Jesus and to Mary, his Blessed Mother. A large cottonwood tree grew in Annette’s backyard, out of place in the New England landscape. As a tiny girl she would meet with Jesus in the tree, entering through the wound of a cut-off branch. She told no one of her adventures and as she grew up tried and tried to reconcile her secret mystical experiences with the harsh teachings of the Church. If the nuns taught that Jesus loved those who suffered as he did, Annette tried to embrace any suffering that came her way as a road to holiness. To please Jesus, she never complained about the abuse and deprivation she suffered, but offered it up to him instead.

As a teenager she turned her artistic gifts to painting lilies in honor of the death and resurrection of Jesus. She identified with Mary Magdalene and painted roses, the secret symbol of the one woman whom Jesus allowed in his circle. Although Annette’s mother was a skilled seamstress and decorative tole painter, she never encouraged Annette’s artistic efforts. She admonished her instead to focus on music, especially church choir. Her mother’s stance softened when Annette was ill, at which time art supplies and supportive attention were both forthcoming.

Annette’s serious childhood bouts of meningitis and rheumatic fever allowed some time and space for her to dream, create, feel some love from her mother, and continue with her mystical explorations. When one is well, Annette learned from her mother, one had better things to do than creating visual art—such as singing, practicing piano, and helping others. Even though she had won a prize for her painting and was encouraged by the nuns, Annette could not overcome her mother’s rejection of her efforts. Her creativity was eclipsed by the belief that the paramount commandment was to patiently suffer and offer one’s pain up to God.

The Catholic Church did not provide an outlet for Annette’s natural mysticism. When she was found eating her lunch in the cemetery, trying to combine service with her closeness to the spirit world, Annette felt sure the nuns would praise her. She was keeping the souls of the dead company, she explained. The nuns called her mother, and Annette was punished. Annette felt that being in a physical body was a sign of impurity, a spiritual defect to be overcome. After all, if she were good enough, Jesus would surely gather her back into his loving embrace in the spiritual realm. Once, Annette made a charcoal drawing of a girl full of sadness and pain. This honest expression of her own emotions through art was rejected by her mother, who pronounced the drawing “awful.”

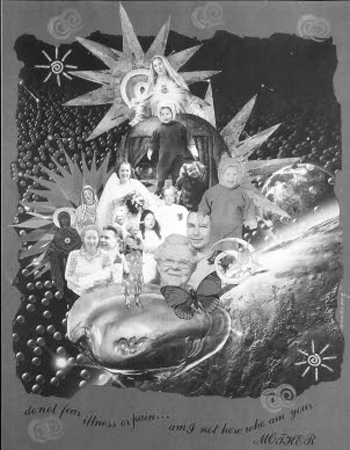

As an adult, Annette made collage her medium of choice. She hunted for images everywhere; no doctor or dentist’s waiting-room magazines were safe. She even convinced the staff of a local bookstore to tell her which nights they deposited out-of-date magazines in the dumpster behind the store. From science and nature magazines, Annette culled images of the solar system, distant galaxies, and the inner workings of the body’s cells. From fashion magazines she harvested all the images of women she could find; all the Mary Magdalenes would be brought home. Women of color, from countries around the globe, began to manifest the Great Mother as Annette accumulated the infinite, multifaceted face of the Divine Feminine. Finally, images of herself, her mother, aunts, cousins, and grandmothers all appeared as the archetypal turned a personal face toward Annette. For it is through working with our own story that we repair the world story. One witness to a collage featuring family photographs (figure 20) reads:

Figure 20. Collage #1, by Annette Hulefeld.

As a little girl, I ran to the backyard and sat under the big cottonwood tree. I imagined that all the stars, the sun, and the moon all were hung in some kind of invisible magic “stuff” that kept them from falling out of the sky or bumping me on the head. Sometimes I wondered what it’d be like if a cloud picked me up and brought me to the stars for a tea party. I of course, would dress in glittered leaves and fancy twigs. In return for the earth dirt I’d bring as a gift, stardust would appear in my pocket. If no one was looking, I’d use my baton twirler to conduct all the different music I heard from all the beings surrounding me, seen and unseen. Back then, no one would have believed me that plants have high pitched voices, or that stones snored, or that lots of birds keep the beat! Had my mother known, she would have placed me back in the bedroom. I was clever and never said a word. I just listened. Yes, I knew that if some “big God” didn’t have a plan for all the wonder, I would not stay alive for too long and neither would anything else. When my mother wasn’t looking or checking up on where I was, I’d take my socks off and let my feet open their eyes to the Mother earth. During those times, I heard the ants giving pep talks to each other for they had so much work to do. I always felt sad for the worms that prayed for rain, knowing when they came up from their home, some shoe sole would “moosh” them to death . . . I learned early that you had to be careful what you pray for . . . Home was and is under my feet. The pulse of Mother’s heartbeat holds me to the earth and moves every step I take.

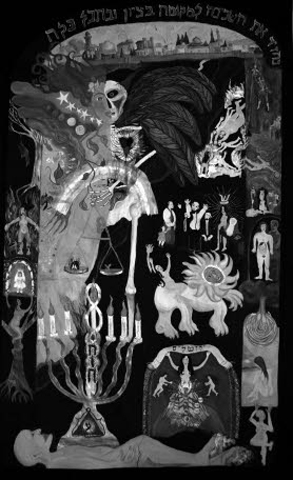

In another piece rendered in black and white (figure 21), the Great Mother speaks to Annette in her witness:

If you look closely you’ll see that I am descending into the space you call the planet. I am catching and holding the fragments of destruction and forming new circles of creation. Towers dominate. Circles contain, form, and move with the rhythms of the Universe. Don’t think for a moment that I am blind to your situation. I have unseen eyes that connect to dimensions beyond your human comprehension. My heart knows all. Yes, I see a cosmic explosion and I see an expansion of the global heart. Now is the time for the planetary Soul to evolve. Divinity is breaking through the human spirit, birthing consciousness. Terrorism cannot destroy Spirit—it cannot split a soul that is wrapped in my Truth, my Compassion, and my Love. Continue to take on the wings of Life, breathe my Life. Stay awake and be my breath.

Figure 21. Dark Mother Ascending, by Annette Hulefeld. Collage.

The studio process helps us see the themes that reverberate for us; these themes, which take form in our images, have their roots in our earliest experience of the world. Images shed light on abandoned parts of ourselves and let us reclaim them. Yet our images are neither personal nor collective, neither therapeutic nor spiritual. They are always and at each moment both and more. Whether we begin with the personal and work toward the collective meaning, or dance with an image from the rich trove of religious history and gradually bring it down to life-size, this work is a spiritual endeavor that helps to repair the world. Every new version of the story adds a diamondlike facet to the whole. As we share these stories with each other in our words and images, even those we might never know may find a note of resonance that helps them on their journey. Through art we infuse new life and energy into the myths that sustain us.

The Sabbath Bride and Friends: Pat’s Story

My major teaching image has come in the form of a giant feminine figure, the Sabbath Bride. She appears in a painting that took seven years to complete and is over eight feet tall (figure 22). She emerged from my struggle with Judaism as my spiritual path, but much of what She instructs me about is how the creative process operates. She brings stories of women’s past and shows me new ways to understand old wisdom. She remains a powerful presence in my life, challenging and comforting me as I continue in learning about art as a spiritual path. She has hung in my studio and now hangs in my home. She also wants Her own book, so She doesn’t tell all Her stories in this one.

Figure 22. Sabbath Bride, by Pat B. Allen. Tempera.

I have been a convert to Judaism for over twenty years when I meet with my rabbi to try to explain my dilemma. I’m intrigued, haunted actually, by a certain image, idea—this Sabbath Bride. The songs and melodies composed by the Hasidim to honor Her will not leave my mind. What can I read, what can I study, I ask him. Oh, and there’s more. I’m afraid, afraid that if I start on this path, I’ll end up, well you know . . . “Having to become Orthodox?” I am relieved when he finishes the sentence, relieved to have this thought out in the open.

I listen distractedly as he acknowledges the conflict and complains that many people seem to see Reform Judaism as the “default setting” of least possible observance rather than a valid philosophical brand of Judaism focused on social justice. Is it most in tune with the practical realities of modern life, or is it a spiritually unsatisfying “lite cuisine”? What is it that I am afraid of? Starting out as a convert, I would be an unlikely baal teshuvah, one who after living a secular life returns to Orthodox observance. I am long married; my child is grown. But something makes me uneasy. Even considering starting down a path that I imagine could lead to a diminished feminine role gives me a chill. I have spent my life finding my voice. I imagine the eighteenth-century Jews who composed these songs that stay in my mind as men, dressed in white, walking out together to go and pray in their shul on Friday night to welcome the Sabbath Queen while the women stay home and take care of the children.

It has been a long struggle for me as a convert to find a balanced path in this maddening religion—not too religious for my husband’s secular family, but sufficient to feed my soul; not taking on customs that feel inauthentic, yet at least considering the wisdom of ancient ideas. I often feel like I’m walking in a labyrinth with electrified walls. I talk with my friend Dayna, who was briefly married to an Orthodox man. “It makes you feel safe,” she says. “You always know what to do. All the rules are there and a whole community that follows them. And there is so much beauty in the Torah.” I have other friends who are creating a sort of neo-Hasidism, taking their cue from the joyful branch of Judaism that flourished in Eastern Europe in the eighteenth century. Known for their dancing and simple wisdom, the Hasidic Jews were all but destroyed in the Holocaust. My friends follow the flowering of the Jewish Renewal movement, whose most prominent teacher, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, is not only a direct descendant of the European Hasidim but also the holder of the World Wisdom Chair at Naropa University, the only Buddhist university in the United States. Reb Zalman has lived the paradigm shift; he embodies the possibility of a new kind of spiritual integrity. Under his amazing inspirational leadership, members of the Jewish Renewal movement seek to reclaim all the pieces: joy, justice, study, equality, mysticism. Still, I notice the women I meet in Jewish Renewal circles are uneasy even amid the egalitarian minyan that has met for several years in my studio and that the men still lead much of the time.

At one service a woman notices my goddess pendant and greets me as a fellow traveler. She is a practitioner of Wicca as well as being Jewish. I mumble something and turn away. Something is churning and restless below the surface that I can’t dismiss as merely New Age nonsense, but it isn’t showing itself clearly. My rabbi recommends some books on Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, but they are dry and confusing. I am circling something, but I am not yet able to see what it is.

It isn’t only my Jewish friends who are struggling with a sense of displacement in their faith communities. Dorie, a close friend and member of the Methodist Church, mourns the loss of a spiritual leader in her community, removed by his bishop for performing and supporting same-sex marriage. A Catholic friend confesses in tears that she can no longer sing at church, that ashes fill her mouth when she tries to pray there, even in her progressive Family Mass community. At the same time, figures of the Black Madonna and the Great Mother are showing up in her artwork.

Suddenly it becomes obvious that I need to explore this idea through creating an image myself. There are prohibitions against making images in traditional Judaism, especially any image of the Divine, but everyone I know seems to think it’s quaint that I even consider them. My intention, to explore the Sabbath Bride, seems straightforward enough. I am drawn to use humble materials—black paper and tempera paint. I am surprised at what emerges; The Sabbath Bride tells me everyone is.

SABBATH BRIDE: My bony hand covers my fertile belly. The raven will drop you there in my cavernous depths and you will sleep and be replenished by wonderful dreams.

ME: Am I grandiose to try and paint you?

SABBATH BRIDE: No. Believe me, I am lonely for the company, I arise from the candle flames . .

I notice that I have painted a menorah, not Shabbat candlesticks.

SABBATH BRIDE: The menorah is a symbol of wholeness, seven candles, seven days. There is more but that isn’t your problem right now. It is a mystical symbol: Shabbat candles are an earthly counterpart.

ME: I wish the flames were lit.

SABBATH BRIDE: In due time.

I let the painting be; I work on other images, including a sculpture of the raven. A month passes before I return to the Sabbath Bride. My intention is To be filled with the light of God. But it is Saturday, a weekend workshop on Shabbat. I write for a while before I begin painting.

ME: I feel blocked, unready to approach you. maybe because it is the Sabbath and I am making, doing, creating, in violation of the law. Yet, I still feel too stupid to be bound by the laws. Are these my laws? Will I be able to paint today? Am I just twisting the rules to think of this work as prayer? Am I the world’s biggest bullshitter and rationalizer?

She is patient as I drift off in my self-absorbed tirade.

SABBATH BRIDE: You don’t seem to want to let me get a word in edgewise . . . it is equally false to abandon your quest because you aren’t following rules. That is the coward’s way out. You must look at every situation, why was the rule made? How does it serve humans?

ME (GRUMBLING): But that’s not what the rabbis say.

SABBATH BRIDE: Just paint.

The all-day workshop drags along. I am stuck—a sure sign that I am avoiding painting something that the image wants, requires. Like a storm it comes: a red horn with blood tendrils extending into the skull, a wing made of multiple sections like an insect wing, a yellow Star of David in the gaping, empty eye socket of the skull, teeth parted as if to speak. I feel afraid. Why have I painted images that are stereotypically anti-Semitic? How dare I paint this? My intention comes back to me: to be filled with the light of God. The image says: The light of God shines making what is in the darkness visible. These images are a part of what you take on in this lineage.

I remember years ago in a mask workshop adding horns to my mask and talking about how I thought it would be great to have horns. Later, a Jewish friend who had been in the workshop told me how embarrassed she was listening to me. I was in the process of my conversion to Judaism then and was unaware of the legends about Jews having horns. Later still I learned that this legend originated in the mistranslation of a biblical passage where the Hebrew word keren is rendered as “horns,” instead of its actual meaning of “shining or glowing,” in the description of the face of Moses upon his descent from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. Did I expect that it would be simple to throw myself in with this tribe and all their historical baggage?

I gaze at the painting and see a flash of a heart-shaped space. I paint it in black over the ribs, but no, it wants to be torn open. I’m too tired; I don’t want to work.

SABBATH BRIDE: Tear the space and let your fatigue pass through you.

I tear the heart. Energy rushes through me.

SABBATH BRIDE: You’re afraid of me aren’t you?

ME: Yes. You seem like an exterminating angel, with your insect wings and your animal’s horn, your bloody heart. Maybe I better talk to Raven, he’s more my size.

I feel so tired. Raven joins the conversation.

RAVEN: Quit your bellyaching, you ain’t seen nothing yet. You’ll be burned at the stake, have a stake driven through your heart before it’s all through, stake your life on it!

ME: What does this have to do with the Sabbath?

SABBATH BRIDE: You’re very literal, you know. Here’s a question, how can you dwell in a palace in time, a place of perfection, when evil continues in the world?

ME: I don’t need more questions; I want answers!

SABBATH BRIDE (SOFTLY): Do you see the moons growing on the vine?

It is years later that I discover the meaning of the moon, its cycles, and their connection to the work. I begin to discern that the great “She,” who is the Sabbath Bride as well as all the other manifestation of Divine Feminine, has a cycle of Her own far greater than I can begin to imagine. A friend recommends a book, Mysteries of the Dark Moon by Demetra George (1992). George writes:

I began to question whether the disappearance of the Goddess during the last 5,000 years of patriarchal rule might not have been due to suppression and destruction by the patriarchy, but was in fact her natural withdrawal into the dark moon phase of her own cycle. Perhaps it was simply that the inevitable time has come in her own lunar cyclic process to let go and retreat, so she could heal and renew herself. And now she must be reemerging at the new moon phase of her cycle with the promise and hope that accompany the rebirth of the light. (p. 62)

What if all the stories we tell ourselves have flaws in them, like the mistranslation of keren? We make up parts to make the story work according to how developed our consciousness is at any moment. Language shapes consciousness; consciousness is expressed in our actions. I begin to chart my own cycle and learn its profound effect on my creativity, relationships, and perceptions. Whenever my work or energy is at a low ebb, I react with alarm, asking myself, “What’s wrong? Why can’t I get anything done? Am I just lazy?” This internal dialogue points to a prejudice in our culture wherein action is valued over contemplation or rest. According to Starhawk, “Light is idealized and dark devalued in this story that permeates our culture” (1982, 21). We have ceded contemplation to the monks and priests, but perhaps now it is time for all of us to integrate this piece as well.

In the meantime, I struggle with the painting. The Sabbath Bride’s seemingly dual nature rivets me. She is creator and destroyer, merciful one and judge, all at the same time.

ME: Does your goodness burden you then with the world’s shadow?

SABBATH BRIDE: Yes, the Christians wanted to keep only the light, to rise out of the earthly ground and be God, to transcend their human aspects. That doesn’t help at all. Those are part of me and of you and are worthy of love.

ME: You seem to carry the projections of vermin, the horn; this line of thought is troubling to me, is it blasphemy? Am I risking a gross distortion trying to understand this? The insect wings are disturbing.

SABBATH BRIDE: Would a Buddhist deny an insect its place of honor in the web of life?

ME: No, I don’t think so.

SABBATH BRIDE: Read Job. All that you see is a manifestation of God’s energy in partnership with human beings. Read Job and then return with your questions.

I read the book of Job. It is an annoying story. God has too many human traits. He bargains with Satan, allowing him to deprive Job of everything—his wealth, his children, his health. Job’s friends come by and find him a wretched sight. Each one exhorts him to seek out his hidden sin; surely, they assume, God doesn’t punish the undeserving. Job has two choices: find his sin or blame God for being unfair. What does this have to do with me? What does it have to do with Shabbat? God is not pleased with Job’s friends. He rails at them: “I am incensed at you, for you have not spoken the truth about me as did my servant Job” (Job 42:7, Jerusalem Bible). God restores Job’s fortunes. What a crazy story. Job hangs in there, holding on to the idea that God sees a bigger picture than he does.

I get two things from the story. First, don’t pretend to interpret the experience of another; there is so much more than meets the eye. This is a helpful insight in refining the studio process. We make the no-comment rule that no one can speak about his or her artwork or make comments about anyone else’s. It seems harsh at first, but the idea is to foster a relationship to the Creative Source by listening to the images that show up in the painting. We listen for the inexorable unfolding of consciousness. Every person has access to a higher wisdom. It can only be gained by making space for it to be heard.

These are alternative voices to the stories we tell off the top of our heads, whether those are the threadbare narratives delivered by popular culture or the parables we swallowed whole in Sunday school. It’s hard to listen with new ears, but doing so is a crucial part of this practice. Long silent and hidden, buried alive between the lines of patriarchal history, forgotten voices and stories are now beginning to emerge from the Soul of the World. Our images are the messengers. It is difficult for us to really listen to the image. Much of what comes to us when we begin this work is static from our inner judge and critic, or echoes of parents and past teachers whose own grasp of truth was incomplete. It is important to hear these messages as well, to honor them and allow them to subside so that the image, finally, will speak and be heard.

Another month goes by before I return to the painting of the Sabbath Bride. I witness: Insect wings to pass the time, relax, face it, there’s something you don’t really want to see right now. It feels good to do menial work, tiny delicate strokes giving structure to something fragile. What is going on here? Something is incubating and can’t be pushed. No forward movement. Sit, wait, wait, sit do nothing. Feel the space between moments, the silence between words, rules change, change of scene, changing of the guard. See your life for a moment as a slow motion film of an earthquake or the stop action film of a seed bursting. Yes, a seed bursting. We don’t see that moment; it occurs underground in fertile darkness. Some things are moving and you can’t see them. Don’t worry, sit silently sit and deeply relax. Sit. I do not sit easily. The best I can do is to be with the painting, making tiny adjustments. That is about as close to the necessity of just being that I can usually get, and it is enough.

A dream comes: I see myself in a costume of the Sabbath Bride. It isn’t a costume in the dream; my skin is painted to resemble the Sabbath Bride painting, or I am tattooed with her image. In another dream a black man speaks to me in the gutted shell of a church. He tells me my work is to found a religious theater. Weeks pass; it is fall. The painting continues to grow organically out of the original piece that held the head and torso. I add pieces of paper to accommodate the image. This patchwork process would bother me except that others in the studio do the same. Dayna works on Faith, a large figure of a woman holding the world together. This process feels like using a paintbrush to rend the veil between worlds. Behind our everyday life pulses a world of primal energy that forms itself into images by way of human acts of speech, writing, thinking, and painting. Ah! Painting comes very close; it captures the timeless coexistence of multiple realities. Perhaps there is a clue to the meaning of Sabbath here. I consider that the imaginal space is the perfection and wholeness we seek to taste by observing Shabbat. I imagine that if I paint joy and spaciousness and all things, they will indeed tattoo themselves invisibly on my skin, and I will wear that knowing into the world. I paint a figure eight over the central candle in the menorah.

SABBATH BRIDE: Stop. You haven’t looked enough.

My eye is drawn to the infinity symbol, eight, the numerical value of the unpronounceable name of God. Endlessness, continuous flow superimposed over the central candle.

ME (TO THE MENORAH): You seem balanced and self-contained; I am working to bring you into focus. You are the source of the apparition of the Sabbath Bride. What do you have to say?

FIGURE EIGHT: I am a moment of stillness. In stillness is the constant subtle flow of energy. Be aware of me, I am an image to guide you. Find my stillness daily, feel my flow, follow my dance, the dance your feet were made for. Be peace, it is different from being peaceful; full of peace is different from full of peas. You will become empty, receptive, waiting. The candle flame then ignites in the space you have made in yourself.

ME: I have been planning to take a meditation class. Does this mean I don’t go to the class?

FIGURE EIGHT: Take your own advice, just do it. In the time you drive to a class, interact, say hello, goodbye and return home, you could have changed your life. Simple means, no wasted effort. I am here in you every moment, never away. I memorize your every heartbeat, quiet stillness, in-action, nonaction. Do less, not more, make space. Stillness is the greatest gift you have to offer. If you can be still, what others see when they behold you is their own true face.

ME: But the detachment of all this scares me. Won’t I evaporate or drift away?

FIGURE EIGHT: No, you think you need to be treading water, but you only need to float.

The following week my intention is to watch my energy and stay with it carefully. I ask this question: Is it sacrilegious to work on the painting of the Sabbath Bride on Shabbat? I have to trust my energy and the fact that I mean no disrespect. I witness: Frolicking fish swimming toward the river, running through Shekhinah’s veins (figure 23). They look so happy. Stars dancing, moons hanging on stems. Does anyone wish to speak?

THE FISH: We are one with life, we are one with the water yet we have form, we sparkle, we shine and ultimately we are eaten by one another. How many times do you need to hear the same story? There isn’t anything to do, to say, to get to this eternal moment. Where is your energy?

ME: I’m tired. I need a rest.

THE FISH: So let go completely of painting, this writing should be writing your way out of it. Leave it on the page so that when you return we are like total strangers you’ve never seen, we surprise you completely. Let this moment end and be open to the next. The secret of Sabbath is to become one with nothingness, rest, annihilation of ambition. Let yourself fall like the figure dropped by the raven. Everything continues but for the moment you cease to be involved, detached you just flow on neutral, no trial no trials and tribulations. You are a dream and your sleep deepens to where dreams can’t find you. When you awaken you have new eyes. You are a new dream. You are all the mystery that is. So accept your imperfections. Stay so small that you could fit inside your own ear and listen carefully.

Figure 23. Sabbath Bride, detail (fish).

If painting brings me to this place of stillness then it is indeed prayer and sacred homage to the Divine. As fish are to water, I am to painting. Yes, painting this way is indeed a valid observance of the Sabbath. It would not be the same if I were painting a sign, or making a painting for sale; but in this way of working I am finding my way back to something ancient and sacred. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, author of The Sabbath (1951) and one of the foremost Jewish thinkers of the century, would deeply disagree with me:

The idea of the Sabbath as a queen or bride did not represent a mental image, something that could be imagined. There was no picture in the mind that corresponded to the metaphor. Nor was it ever crystallized as a definite concept, from which logical consequences could be drawn, or raised to a dogma, an object of belief. . . . Some do not realize that to personify the spiritual really is to belittle it. (p. 60)

I would argue that the way in which I made an image of the Sabbath Bride was a deeply devotional act. I would not expect someone reading this book to adopt my image of the Sabbath Bride any more than I would try to pursue the black woman who scooped up the child at Six Flags and try to get her to found a church. The point is that in order to see the Divine, one must see the Divine. As I and other women engage with the feminine aspects of God, we see Her in many places—in the eyes of the woman selling us fruit in the market, in our child’s nursery school teacher, in our elderly mother-in-law or our roller-skating neighbor, and in each other. Rabbi Heschel’s fear of dogma is groundless if we treat the image process as a continuous midrash that emerges over and over in new forms. To refuse to accept this form of teaching, to denigrate the power of the imagination as a means of God’s instruction, is to insult God, who created that imaginative capacity in human beings. One suspects God has been waiting for us to use the imagination to praise creation rather than to perennially destroy it and each other as we have done.

An artmaking space is a mishkan, a portable sanctuary. Each artist working there is alone with her image and the message it brings as well as being in subtle communion with others in the space. This is a feminine form of cultural practice. The great male artists of the past had ateliers where other artists worked for them as assistants or apprentices. The studio feels more to me like a temple where we are all engaged in different acts of service to the Divine. The witness of others and our ability to struggle alongside them deepens our engagement in the process. Safety grows as we learn to travel back and forth between speaking with our images and attending to mundane tasks like washing brushes and refilling water containers for painting. The daily ordinary work reminds us that we are not ascetics flying off into the ethers but everyday mystics choosing to dedicate ourselves to the Soul of the World by paying conscious attention to what arrives in the image—whether it’s a Goddess figure, a lesson about our family, or a practical hint about how to balance the checkbook.

The work of integration happens simultaneously with the work of revelation. Washing brushes is a key task in studio practice. It engages us with the consequences of our materiality. Artists are often surprised when I tell them that some of the paintbrushes in the studio are twenty-five years old. Every time I wash a brush, rubbing the bristles firmly again and again against a bar of soap and rinsing and rinsing again until no more color comes out, I am performing an act of service. I serve the community of artists who share the brush. I honor the hog or sable or squirrel whose bristles create the brush, the tree who gave wood for the handle, the craftsman who fashioned the metal ferrule out of Earth’s ore. By my action I say these gifts are valuable. I care for them. I appreciate them. I share in a subtle way with all the artists who have handled the brush. Brushes improve with use and kind handling. I have bought inexpensive brushes at flea markets for a dollar apiece. They receive the same care as the most expensive sable brush. As I rub and form the bristles against the soap, they become more resilient and shape themselves to the creative act.

Care for one’s tools is an honored craft tradition. Mindfulness transforms this simple act into a meditation on our connection to one another, our responsibility to the community of creators and to the images that arrive for all of us. We are not spiritual beings when we meditate and materialists when we clean up. We are at all times multiple realities inhabiting a particular body. The conscious bringing together of the mundane and the sacred dissolves their distinctions into humble wholeness. This is one of the primary tasks of a spiritual practice: to learn to love it all and value the simple, the everyday.

When we imagine that our connection to the Divine depends on rare and special conditions, we deprive ourselves of the continuousness of life flow. We also imagine that our small acts of violence in daily life somehow don’t matter, that they are separate from our “spiritual” lives. We fail to see that rushing to get somewhere makes us late, that it forces us to drive somewhere that we could easily walk, and that this is an unnecessary act of harm both to the air, which becomes polluted, and to our bodies, which become stressed out and weak. Images bring us awareness of our mistakes, our peak moments and our quiet satisfactions. If we pay attention to all aspects of the work, our discernment of the Divine in all things grows. Without the brush, there is no painting. We can no longer value our product, the art, over the brush when we wake up to their interdependence. The Sabbath Bride makes a spacious mishkan where I can learn and relearn these lessons.

Another month goes by before I return to the Sabbath Bride. My intention is to learn why I’ve been avoiding the work.

ME: Why am I afraid of you?

SABBATH BRIDE: Because knowing me will change your life. You are suspended in mid-air above my cave and you can take as long as you like to fall into it.

ME: This Shabbat is my birthday.

SABBATH BRIDE: Am I invited?

ME: I’m not sure. I don’t know if I can make that commitment. I have no idea what I am talking about. Do I think that inviting the Divine Feminine means sitting through a dull Friday night service in the synagogue? Is that really what I imagine is required? Will my family resent me, think I’m being “holier-than-them” if I demand they attend services? Will I be separated from them if I go alone? Will I lose them?

SABBATH BRIDE: I don’t give coming attractions, stay in suspended animation as long as you need to. I’ve waited centuries, a while longer won’t matter.

I am struggling with the two sides of the figure: What is the interaction between them? I feel stuck most of the time, doing little things in the painting, like brightening the figure eight. Finally I attend to two small drips of paint on the leg, “mistakes.” A blue drip becomes a rabbi/angel.

I thought to paint a cave around him, a spark imprisoned; but the cave becomes a house—no, a church. A cross and a swastika appear, and then the house/church bursts into flames. Then there’s a pink drip; maybe it will be a little child—life and innocence to balance persecution and destruction. No such luck. Instead it becomes “insect-man,” a naked, mayfly guy looking all too gleeful. Then, holding the two of them, a pair of scales appears (figure 24). This is justice?

Figure 24. Sabbath Bride, detail (scales).

ME (WITH MILD SARCASM): So what is the lesson, Sabbath Bride . . . that justice is absurd?

SABBATH BRIDE: As usual, you don’t let me get a word in. Did you happen to notice that inside the burning building your rabbi-angel is quite unscathed?

ME: Yes, but how is he balanced by larvae man?

SABBATH BRIDE: So, you think you know balance when you see it?

ME: Well, yes, I do think so.

SABBATH BRIDE: Well, think again. You could, well, one could, go to your death a martyr. Bad, right?

ME: Yes, very bad.

SABBATH BRIDE: One could be reborn as an insect.

ME (EXASPERATED): So what’s the lesson? Nobody gets a fair deal? Everything could always be worse?

SABBATH BRIDE: Quit jumping to conclusions, you’ve got more to learn.

I seek to understand the dark place in the Sabbath Bride. My intention is a question: If I am dropped into this pelvis full of flames, where do I land? I create a small image to explore what might be in there. It turns out to be a place full of glorious lights, swirling energies, in which the figure, me, is unimaginably tiny (figure 25).

Figure 25. Place of Glorious Lights, by Pat B. Allen. Acrylic paint, glitter.

ME: It seems very random to me.

SABBATH BRIDE: It’s not. It’s just that you can only perceive the tiniest fragment of the pattern, a fraction of a fractal, so you can’t see the wholeness.

ME: I simply have to trust that it’s there.

SABBATH BRIDE: You don’t have to.

ME: I do. I do have to trust, and who am I talking to anyway?

SABBATH BRIDE: The Soul of the Universe, the Sabbath Bride, Shekhinah, whatever you’d like to call me.

ME: This is starting to scare me, annihilation comes to mind.

SABBATH BRIDE: Annihilation isn’t a concept here, purification, clarification, if you notice the stream of green in your small piece, it is a bit narrow then it reaches a wide, endless place.

ME: Are you saying I can be a channel for love?

SABBATH BRIDE: It is the sole purpose of a human life. The first step is to let go of density and return to energy.

ME: Do I have to die to do this?

SABBATH BRIDE: Not usually. Some do, it’s hard work to channel light in a human form, but necessary. Accept everything that comes to you; see into it from a place of energy. Remember that the pattern is bigger than you can see and the lifeline goes into an endless well, my womb, the void. Just picture that when you lose track of what you’re doing.

ME: Why are there different kinds of energy?

SABBATH BRIDE: There are three, that which emanates from the figure, the weakest because it has to travel outward through dense human form and it’s just a spark to begin with. Then there’s the white, swirling energy that comes from above and is multifaceted, universally so. It can end up manifesting as anything that you imagine. Then there is the green, which is My energy and it travels upward. It is love and when combined with the other two makes wholeness.

In the picture the different energies are represented with glitter in different colors. It is as if a close-up detail of the pelvis of the Sabbath Bride was taken in a snapshot.

ME: Why is the container of these energies a pelvis bone?

SABBATH BRIDE: You are a woman. You have an extra seat of love. Men have just their hearts. You have a womb, which is very like a heart, a “bleeding heart,” you’ve heard that term? It is code for feminine wisdom, the sacred heart also.

ME: So as humans we are supposed to . . .?

SABBATH BRIDE: Become conscious that you are energy, become conscious that you attract energy. Become conscious that without grounding your energy and the cosmic energy you can destroy yourself and the world.

ME: Okay, that’s pretty simple, how do we know if we’re doing it right?

SABBATH BRIDE: By the results, alignment of these energies never causes chaos. Not that all’s a bed of roses but get used to how it feels to be lined up straight and you’ll know when one is out of whack.

ME: But how?

Figure 26. Male Trilogy: Fool, Emperor, Death, by Pat B. Allen. Gouache.

So much of my work has been to receive and express images of the feminine. I am surprised when a trilogy of male figures emerges in a series of small paintings (figure 26). They are The Fool, The Emperor, and Death, and they seem to correspond to the creator, preserver, and destroyer, a feminine divine triad that appeared years ago in my work as a series of sculptures. Intrigued, I write a witness.

ME: How is your energy different from the female trinity?

THE FOOL: We’re really the same—wild, electric, elemental, not departmental, sentimental, mental in green tights. I’m poised on the crown of the world, my faithful Fido in his party hat. We’re both dressed for success, success of a party, that is.

ME: Why are you yellow?

THE FOOL: Yellow? Hello! Color of light, bright sight and when you block me you are full of “right.” We dance against an endless sky, not bound to earth, so watch out, we can make you fly, into space without a trace, which is why you need the other guy.

THE EMPEROR: I reign over the earthbound and matter, I make decisions and carry them out fertile, blooming. My throne is outside on the earth, near water, sky and sun. I am kind and fair and get things done. I’ve told you that my energy is at your service. Use it. Enjoy it. You’ll get things done you could never dream of, large and small.

DEATH: My energy is slayful, not playful. Without E-man [the Emperor] I’d cut down everyone who looked at you cross-eyed. I don’t mind creating havoc. I’m not as well intentioned as my sister Kali. I’d kill for the taste of blood, cull the weak, who needs ‘em, off with their heads!

ME: Okay my head is spinning. So all together, if I may summarize, your energy, each of you, is more active and action-oriented than the feminine expression of the same principles. How did the Emperor get his heart?

THE EMPEROR: I honor the earth, the elements, sun, sky, air, in me they all unite. I am whole; I have experienced the hieros gamos. Thank goodness or I’d never keep the other two in check!

I feel resistance to this male energy, but I am drawn to the kind eyes of the Emperor.

THE EMPEROR: Your quest is noble but not without suffering. For you to accept my energy means you will change. My netted armor doesn’t conceal my heart, it is as open and vulnerable as you must become.

ME: But women are more vulnerable, our hearts are more open.

THE EMPEROR (SHAKING HIS HEAD): No, you are mistaken. The heart of man is more easily broken, that’s why we are the warriors, to prevent the possibility.

ME: But you have no weapons, you have corn, a flower, an owl.

THE EMPEROR: My powers don’t require weapons. I no longer need to fight. Believe that if you place yourself here and put me and my throne in your heart you will be able to be both brave and wise, without weapons.

ME: Was painting the blue clasp at your neck a mistake?

THE EMPEROR: No. The blue jewel is my will. Will is what you must align, align your will and be well.

Something made me put on a lapis lazuli ring and bracelet this morning. Yesterday I purchased a lapis pendant that resembles the clasp on the Emperor’s robe. I have the three paintings of the male trilogy on my writing table to aid the manifestation of my dreams. I feel their energy calling to me. A stream of images of the hieros gamos, the sacred marriage of male and female energy, snakes among the other work I do.

A week passes; I come to the studio fighting a cold. I write as my intention to know why I am congested. I begin my witness by addressing the Emperor.

ME: So there you are on your throne with all your accoutrements of feminine power and wisdom, but where is the actual woman?

THE EMPEROR: You are the woman, I have learned these things so that I can carry the signs of feminine power but I am a man, balanced by male knowing.

ME: Do you know why I am congested?

THE EMPEROR: Con-gested, con-gestation. You are growing a new awareness. As I have studied, honored, and revered the feminine, you must study and honor the male.

ME: Is that to be through Judaism?

THE EMPEROR: Yes. You will need to study with a series of men, you will gain command of certain areas, and you will combine them with the wisdom of the feminine and produce a new awareness.

ME: Isn’t that awfully grandiose?

THE EMPEROR: No, you said you would do this, I send you forth with this task.

ME: So why congestion?

THE EMPEROR: There is a certain stuffiness, an inability to breathe in the tradition–you can’t hold this stuff down any more. Let go of your fears, find my name in the Bible and let go of your fears. Study what comes before you.

ME: I’m afraid of the men in black coats, that they will kill me, the nonreligious Jews will kill me, my Jewish friends will be jealous of me.

THE EMPEROR: Welcome to the tribe! People may take issue with you but you really have to go forward. Let go of your inhibitions, embrace study and go forward.

ME: What am I still missing?

THE EMPEROR: It’s not the Sabbath Bride you fear deep down. You don’t fear the feminine, nature, or the angel of death. It is man, men; the masculine nature that you fear will awaken your old pattern, your isolation, your loneliness. You fear I am sending you on a lonely hero’s journey, but it is not so. You will have many loving companions, you will have teachers, helpers, support and recognition.

ME: Then why am I so resistant?

THE EMPEROR: The male consciousness you had before was a cruel jailer. It’s hard for you to imagine my vision but trust; it will be fine.

I notice my right side is stuffy and blocked.

THE EMPEROR: You fear domination by this consciousness. The feminine is powerful and more comfortable a haven, now that you know and respect Kali. But remember, there was a time when you deeply feared and distrusted the feminine.

ME: That’s true, but I am also afraid of having to be a stupid kind of female to balance the male you are talking about.

THE EMPEROR: Quit trying to figure it out. Breathe deeply. You need not hide the compassion you’ve gained to accept the power I offer.

ME: What do I need to do?

THE EMPEROR: Just keep your eyes open. Who is the bridegroom of the Sabbath Bride?

ME: Israel.

THE EMPEROR: Learn all you can.

ME: Are you connected to my Irish ancestors?

THE EMPEROR: I am connected to all the ancestors of every land. This is an old road we’re treading here. Right now your task is to learn from men all you can about Israel.

As I write this section, I experience a strong sensation on my left side; my eye, neck, shoulder and rib cage all pulse. I consider the fears I expressed in that witness seven years ago in my conversations with the Emperor. I address my body.

ME: What are my present fears of my feminine nature?

BODY: You worry about putting down Kali’s sword of truth; you worry about the reticence you notice in men, their ability to hold their thoughts and words to themselves.

This sounds true. I gained my voice through my work with Kali; and now I’m afraid I’m being asked to give it up. As I write this dialogue, the discomfort in my head and neck eases somewhat, but not completely. A painting of Kali done by a friend has repeatedly fallen from where it hangs in my studio window. It occurs to me to witness Annette’s image of Kali. I take Her down and place Her next to me. She says: It is time for union, do not resist, my job is to prepare the way. You’ve learned to speak the truth, now BE the truth.

Speech, this has something to do with my speech. The Jewish teaching lashon hara instructs us not to speak of others. This is not just the obvious prohibition against speaking ill of someone, but rather of speaking about others at all. When I first read about this teaching in a book by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, Words That Hurt, Words That Heal (1996), I frankly found it preposterous. So many of my interactions with women friends are spent talking about ourselves, our partners, other women, our families. It is the primary source of bonding and intimacy that we share.

Growing up, I had been deprived of this kind of sharing by the terrible stoic muteness I received as a silent teaching from my mother. She chose not to speak about her pain as she suffered with cancer or about her anger at my father, though her frustration often seemed to be expressed through injuries to herself and accidents. Years of therapy and countless images of Kali helped me to release a backlog of tears, fear, and pain. Sharing those opened me to the more mundane kind of intimate talk that women share. Am I being asked to turn my back on this kind of connection, or is it enough to make an intention to do no harm and work to stay mindful of that intention? The studio teaches us the power of words, new ways of speaking our truth. It is not the gut spilling of therapy groups. More often the stories we tell come out in metaphor, not a literal rendition.

I reread more witnesses from seven years ago. I ask the Emperor to help me discern my role.

ME: What does it mean to make art and be of service?

THE EMPEROR: Your service has to do with transformation, the recognition and understanding of evil, its intricacies, its process, how it comes about, its energy. You must learn about evil, ways to respond, react, be in relation to it, this is your service.

I can’t take on this task without alignment of body, heart, and mind. I experience such separation in my life. Setting up the studio in such a way that I can facilitate and participate is my way of trying to resolve the awful separation that comes from overriding the heart with the mind. I create a thin, attenuated figure out of tape and foil that tells me he embodies the illusion of separation.

THE FIGURE: That is my reality, alienation. Without the mirror of others I starve to death. I am the hero, alone except in very prescribed relation to others. I fight, I rescue, I honor but I also suffer because the time for heroes is over. You must awaken to separation, to know it fully in order to have the will to return to the One. Use it and find your way home, home to wholeness, the oneness that is true. Separation is an illusion but I exist in everyone. I, the suffering, separate being, whatever is not allowed, is cut off, and sent away. You must go from oneness in order to return to oneness by choice. This life is a dance between the perceptions of oneness and separation. Meditate on me, strive to see me, know I am in each person.

ME: Won’t it overwhelm and exhaust me to see the suffering in people?

THE FIGURE: No and yes. I said see, not necessarily do anything. See and let what you see pass through your personal heart into the heart beyond your heart. Let your personal heart be melted, shattered. In the personal heart the suffering of others lodges like glass shards or hardens the heart like stone. The heart beyond your heart is like water, it washes, cleanses, purifies. If you saw someone actually in my state, to feed me would be to kill me, yet that would be the impulse of the personal heart. The heart behind your heart knows to bathe me, hold me, honor me, witness me, purify me and later, food for me will appear. The pelican tearing her own flesh to feed her young is not what suffering needs. Hold, see, witness, purify, redeem your own suffering and that of others. Then watch it turn into a dove and fly away. This is witness. This is transformation.

How is it possible to learn this way of being with suffering? How is it possible not to be like Job’s friends—judging, seeking answers and explanations, seeking to fix and to mend? How is it possible to know what is right action, as opposed to mere reflex action that does more to comfort the observer than the one suffering? Painting teaches this lesson. When I stay with what doesn’t work, what is frustrating and unaesthetic in a piece of work, I make space for the “Aha!” of the aesthetic resolution. This is the moment of transformation, when a shift occurs, due to honest witness; something softens, opens. Is it possible to live this way? I think so, with art as a path. Painting, for example, keeps the heart that is beyond the personal heart, open. I am present as a witness, a conduit for divine energy.

When you look at what is happening to our world—and it is hard to look at what’s happening to our water, our air, our trees, our fellow species—it becomes clear that unless you have some roots in a spiritual practice that holds life sacred and encourages joyful communion with all your fellow beings, facing the enormous challenges ahead becomes nearly impossible. (Joanna Macy 1990, 55)

I need not judge or label another’s experience but merely be present to it. In that space of acceptance things begin to soften. During witness reading in the studio sessions, I find that the artmaking I have just done, whatever it has been, opens me so that the words of others can fall into that place of spaciousness and compassion. A ground has been prepared for true listening. “When we bear witness, when we become the situation—homelessness, poverty, illness, violence, death—right action arises by itself” (Glassman 1998, 84).

So I turn to the Sabbath Bride, who began this story. There is a naked androgynous figure at the base of the painting, looking up at all that is unfolding. At the top of the painting is an ancient prayer: Nachazir et ha-Shekhinah limkomah b’Zion uva-teivel kulah (Let us return the Shekhinah to Her place in Zion [Jerusalem] and in all the world). Shekhinah, the feminine face of God, has always been hidden in plain sight in the Jewish liturgy. I address the prone figure.

ME: How does all this work?

HE/SHE: Mandela sat in prison holding the space of peace and justice inside himself. He is that now. You are asked to hold this story.

I remember traveling to Jerusalem in 2001, about six months before a devastating cycle of attacks and reprisals between Israel and the Palestinians began. I was privileged to say the prayer for Shekhinah’s restoration on the Mount of Olives with the group I was traveling with, which included spiritual teachers and authors from many traditions.

ME: Is the awful war and violence part of restoring Shekhinah to Zion?

HE/SHE: I am just a visionary. I see what has been centuries of torture and violence born of fear that the Divine had abandoned the world. Those of you alive today must decide how long war must be the way you choose to usher in Her return.

ME: Fear.

HE/SHE: Of course there is fear. What have you learned from all your work?

ME: Create a space, an open space for change to occur. Have an intention. Witness what is, then ask for a vision of the world you’d like to see.

While writing this chapter, I came across an old issue of YES! A Journal of Positive Futures. I flipped through the magazine and found an article titled “Building a New Force” by Michael Nagler, a founder of the Nonviolent Peaceforce. Begun in 1999, NP aims to “create space for local groups to resolve their own disputes peacefully” (2002, 49). At the behest of local groups, NP deploys hundreds of peace workers to protect human rights, prevent violence, and enable peaceful resolution of conflict using such methods as protective accompaniment, international presence, interpositioning, and witnessing. NP witnessing includes monitoring events and disseminating information internationally to the media and the general public via words and images.

What most impresses me is the ethic of non-partisanship that NP espouses. You are not there to protect one group from another even when your actions do have that effect. You are there to protect peace, for everyone, and that means getting in the way of violence against anyone as did the African-American woman from Michigan Peace Teams who covered a fallen Klansman with her own body when he was attacked by an anti-racist mob. (p. 51)

I return to my dialogue with the prone figure.

ME: Can you help me summarize this learning?

HE/SHE: It is time to take what you’ve learned inside the studio outside into the world. Peace is the message. It is not some sort of insipid, solemn, limp thing. Celebration of life, that is what peace is. You can get peace through war, by simply bankrupting yourselves, wearing yourselves out. That is one way to create the necessary space. This is a long and painful and difficult and unnecessary path. You can have peace if you become peace. Ride the Life Force Lion, you do not need to fight and destroy him.

When I consider the words of this witness I have a deep sense of not knowing how this wisdom will manifest, yet at the same time a feeling of hope. To celebrate life, can that really be our primary job? It feels too good to be true, not serious enough. Yet, as I write these words, I feel the smiling countenance of the Great Mother, of all the women in Annette’s collages, of the Sabbath Bride welcoming me home.

Let us hope that, during the Goddess’ long sleep she has effected a transformation at the deepest level of the feminine energy that will allow us to pass through the destruction of the old order, like the Phoenix, rise out of its ashes and soar. . . . Transformation can only occur in the dark. (George 1992, 105)

I accept this challenge. I know in my deepest self these words are true.

HE/SHE: Be a good and neutral mirror, let your heart break. Be a witness, not tied to a stake before a firing squad but standing with arms wide open, breathing in, breathing out, feet planted firmly on the ground. Do not try to turn the tides with your brilliant explanations. Even when you witness a fevered frenzy, a breaking all apart, breathe and breathe again. Sigh. Soon, actually not always soon, sometimes it takes a very long time that feels like eternity, but lets say soon anyway. Soon the turn to laugh and dance will come around and you will be ready: limber, warmed up, and eager to join in.