3 Compromises with Capitalism

CRAIG CALHOUN

After World War II, democracy came with surprising rapidity to seem normal in much of the world and a widespread aspiration elsewhere. Europe played a central role, as it had in the war. But the impact was global.

Democracy was joined with the building of strong institutions for social welfare in the project of reconstruction after the war’s devastation. Labor and social democratic parties came to the forefront as advocates simultaneously for political rights and socioeconomic inclusion. Communists were prominent in politics and unions, but usually hesitant about pursuing democracy as such in still-capitalist societies.1 Crucially, conservative parties throughout Europe accepted democracy and even welfare state institutions. The common experiences of devastating war and depression before that both played a role. Had the Right remained resolutely in opposition, much less could have been done.2 A kind of compromise was forged between democracy and capitalism.

Such a compromise had already been developing in the United States, advanced by the New Deal, and in Britain, though Labour’s biggest successes still lay ahead. Democracy was built in ways that facilitated rather than threatened capitalism, but capitalism was subjected to regulation and reform. Contrary to far-left arguments that nothing significant could be achieved by democratic reform in capitalist societies, there were remarkable improvements in many of the social conditions for democracy—in the United States, Canada, and other relatively rich countries as well as in Europe. While tax rates were high, the foundation of industry on private property was not challenged. Of course, compromise is a limit as well as an achievement. There were struggles to try to improve its terms and balance. The Cold War, political repression—and indeed repression more generally—all curtailed freedom. But the accomplishments of the era stand as demonstrations that concerted action can strengthen the foundations of democracy.

State institutions played a central role in this. They provided citizens with greater security—a stronger safety net against unemployment, poverty in old age, and less predictable misfortunes than workers and their families had previously known. They provided direct support for health care, the quality and supply of food, and sanitation. They supported scientific research and dramatically expanded access to education and otherwise elite culture. They built roads, extended the electrical grid to rural areas, insisted that the post needed to reach all towns and that trains needed to stop at a range of local stations not just metropolitan hubs. They also worked to end poverty and reduce inequality, but as the list above suggests this hardly exhausts the notion of “welfare.”

Central though state institutions were, building democratic society meant more than strengthening the democratic state. Associational life was crucial. Trade unions secured not just higher wages but job security, pensions, and health insurance for their members (whether through market provision in the United States or national health care elsewhere). An enormous range of organizations proliferated in civil society, complementing what state institutions offered. From Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts to churches and philanthropic campaigns for medical research, private action was collectively organized for the public good; local communities were largely self-organized.3 This played a proportionately larger role in some countries than in others but was nowhere absent.

This chapter begins by examining the consolidation of democracy—and social conditions for democracy—in the first decades after World War II. There were always limits and tensions, of course, but the achievements are instructive. In many ways, they represented a positive culmination to the great transformation inaugurated during the Industrial Revolution (at least for the global North).4 As we saw in the last chapter, that transformation brought both dramatic expansion of productive capacities and massive disruption to the lives and livelihoods of working people. Older communities and coping mechanisms were undermined. Replacements were slow to develop and often actively resisted by those with capital and power. State policy was informed by a “liberal” commitment to the freedom of property at the expense of equality or solidarity, which blocked support for those displaced and sometimes actively made things worse.

The resultant disorder brought a chaotic mix of large-scale displacements and migrations, crime, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the rise of fascism and the war itself. More constructive responses to this disorder and disruption came from charities, churches, trade unions, and social movements, Crucially, social democracy sought to extend earlier, limited political democracy and at the same time directly improve economic and social conditions. We understand this broadly to include American mobilization for the New Deal and civil rights, democratic socialism, and other mobilizations that informed the building of “welfare states” from the 1930s through the postwar boom.

We begin with the boom years. These did not perfect political democracy; bring perfect economic equality; or sustain solidarity enough to include minorities, respond to social movements, or weather dramatic cultural and technological changes. But they did bring forward movement. The second part of this chapter examines how that movement was blocked and partially reversed and how a new political economy shaped the degenerations of democracy that followed.

Les Trente Glorieuses

Looking back from recession and slower growth in the 1970s, a French author labeled the postwar years les trente glorieuses.5 The term caught on. Like the counterpart term “postwar boom,” this pointed above all to rapid economic growth. We use the French term in this book to emphasize a wider experience of social improvement underpinned by that growth, as well as by public policy.

Growth was especially dramatic by comparison with the previous decades of war and depression. As important to democracy, however, was the relatively wide sharing of wealth and income, the opening of new opportunities, and the building of new institutions. Pension schemes, unemployment benefits, and health insurance brought a new sense of security. Fundamental improvements in public health show how this extended beyond the narrowly economic. Maternal mortality, for example, had long been an almost commonplace tragedy. Over thirty years it became rare in the world’s richer countries.6

The American economist John Kenneth Galbraith suggested that growth was bringing a long-term transition to “the affluent society.”7 The middle classes flourished, and there were relatively widespread chances not only to move from the working to the middle classes, but also to enjoy better standards of living as workers. Rising consumerism was variously loved or criticized, but cars, refrigerators, and televisions all became increasingly standard—along with processed food and pre-prepared meals. So did higher levels of education. During les trente glorieuses, the proportion of American children enrolled in school went from just over half to 90 percent. The proportion of adults who had finished secondary school doubled.8

The 1950s are often remembered as a culturally stifling era from which the 1960s were a release. Though not without an element of truth, this caricature is misleading. During the 1950s, the United States did see more than a little conformity, including the rise of the grey-suited “organization man.” There was also the Red Scare, a mass panic over communism promoted by the populist senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (whose very name signals repression of diversity). In Germany, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer balanced “deNazification” with protecting the careers of former Nazis and curtailing public debate and dissent. In France, Charles de Gaulle reigned in the name of conservative nationalism. But eventually there was growing freedom in politics and in personal life, as well. It is partly because of the growth in cultural and personal experimentation that the 1950s are remembered as repressive: they produced innovation that some would try to stifle.9

The 1950s saw a flowering of modern art and expansion of museums, galleries, media, and education to open up wider access to “high” culture.10 There was excitement in literature and expansion of the reading public. Both schools and museums became more accessible, especially to the growing middle classes.

The Harlem Renaissance may have ended in the Great Depression, for example, but jazz music continued to flourish. Indeed, jazz was both multiracial and international, linking the United States to Brazil, Japan, South Africa, and Ethiopia. Rock music was even more alarming to the cultural stiflers.

There was a utopian dimension to the Western postwar project. Societies devastated by war and those that had languished underdeveloped (or dominated by colonialism) were to be rebuilt in the context of new transnational structures that would ensure peace and human rights as well as economic prosperity. The United Nations was established in 1945 and the Universal Declaration on Human Rights adopted in 1948. The Bretton Woods institutions (the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund) preceded the United Nations by a year, perhaps signaling the primacy of economics in the new global order. Here too Western democracies were ambitious, envisioning a process of “modernization” that would bring economic advancement by extending capitalism while also promoting democracy.11

Retrospectively, the Western Allies declared that saving democracy had been the purpose of the war. They demanded democratic constitutions for Japan, Italy and West Germany. East Germany, of course, joined other communist countries in claiming the mantle of democracy for a political system that put material equality ahead of political freedom (yet in the long run failed to deliver comparable prosperity). Throughout the ensuing Cold War, the West fought for a “freedom” that combined democracy and capitalism.

In the often insular and isolationist United States, and alongside campaigns for Americanism, there was an unusually high level of interest in the rest of the world. There was a surge in foreign language education, and academic area studies flourished—and it is noteworthy that both declined precisely during the era of so-called globalization that began in the 1970s. Americans became tourists and foreign travelers and flocked to “world fairs” (as they had at the end of the nineteenth century). The United States understood itself as the leader of the “free world” and confidently expected modernization to bring both unprecedented prosperity and democracy.

As evidence of their leadership, Americans could point to the Marshall Plan. This was somewhat self-interested and not quite utopian, but still generous in its combination of assistance for European recovery and investment in a growing capitalist market. A similar effort helped renew the Japanese economy and create a strong long-term relationship with the United States. And there is no denying the utopianism of projects such as the Peace Corps.12

The call of utopia was strong as Western Europe embarked on an agenda of integrated economic development. This started with postwar material reconstruction but always incorporated the goals of ensuring peace and providing the basis for democracy. The European Coal and Steel Community, established in 1951, became the basis for the European Economic Community with its “common market” in 1958, and then the European Union from 1993. Economic goals dominated, though articulated in terms of freedoms—free movement for goods, services, people, and money. Political integration increased over time, though accompanied by sharp debate over just how democratic the EU itself was. Whatever the “democratic deficit” of the consolidated structure, only democracies were admitted as members. This was a key basis for inclusion of Greece, Spain, and Portugal in the 1980s and of Eastern European countries starting in 2004.13

Disturbingly, leaders of the Western Alliance seemed to feel little contradiction in declaring themselves the tribunes of democracy while denying it to the colonies over which they ruled. France fought a brutal war to resist Algerian independence; Belgium was murderous in its effort to hold onto the Congo. Indonesia struggled for four years for independence from the Netherlands; former World War II allies at first supported the Dutch but then switched to applied pressure for recognition of the new state. And, of course, the heritage of settler colonialism was felt in apartheid South Africa (and in treatment of indigenous populations in many countries). Even the United States, with no formal colonies, resisted calls for democracy in Puerto Rico and intervened against democracy throughout the Americas and Caribbean. It also, of course, intervened in a Vietnamese civil war with roots in an earlier defeat of French colonial rule.

Still, whether the glass was half empty or half full, there were also successes of decolonization. Greatest among them, perhaps, after long struggle with Britain, India was democratic from its independence in 1949. The Philippine Republic gained independence in 1946, though the United States retained substantial influence.14 Korea gained independence from Japan only to fall into Cold War division, but democracy gained strength in the South. Ghana led a succession of African countries to independence and democracy in 1957.15 Haiti had led the way to independence for Caribbean countries already in the eighteenth century, but in 1962 Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago started a new wave of independence and democratic transitions in former British colonies.

Postwar international optimism was never complete. There was fear of nuclear war in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; this informed campaigns for nuclear disarmament that already in the late 1950s helped to shape the rise of the New Left. Cold War suspicions and anxieties were pervasive. “Losing” China was disturbing to Western and especially US policy elites and was followed by full-fledged war in Korea. There was near-panic in the Cuban Missile Crisis and post-Sputnik mobilization for the space race. But even these alarms were channeled into a more positive story of accomplishments. Sadly, the same optimism informed the United States’ growing war in Vietnam, which would help to end the postwar era.

In short, this was an era of contradictions: continued repression and renewed struggles for liberty. This was not just true internationally. Was the American civil rights movement an optimistic sign of change or evidence that resistance to full democracy continued? Certainly, as discussed in the previous chapter, it was only one phase in a very long American struggle with the heritage of slavery and continuing racism. It was inspiring, but was it more than two steps forward and one step back? Or less?

The civil rights agenda could be construed narrowly and negatively as ensuring that Black Americans were not legally disadvantaged compared to whites. This would require removing racial restrictions on voting, housing, jobs, and education. Or the agenda could be understood more broadly and positively as a call for all Americans to enjoy the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness articulated in the Declaration of Independence. This would require not just that Blacks should be no worse off than whites, but that they should enjoy better lives, together with whites, in a freer, more equal, and more unified society. Interpreted this way, achieving civil rights required social transformation. Martin Luther King Jr. articulated this social democratic (or democratic socialist) agenda as he called for a Poor People’s Campaign and endorsed the Freedom Budget that Bayard Rustin developed for it:

The long journey ahead requires that we emphasize the needs of all America’s poor, for there is no way merely to find work, or adequate housing, or quality integrated schools for Negroes alone. We shall eliminate slums for Negroes when we destroy ghettos and build new cities for all. We shall eliminate unemployment for Negroes when we demand full and fair employment for all. We shall produce an educated and skilled Negro mass when we achieve a twentieth-century educational system for all.16

The Poor People’s Campaign climaxed in 1968 but ultimately failed to achieve traction. King was murdered. The civil rights movement he had led was challenged not only from the Right but by advocates for Black Power. Republicans made electoral gains. Vietnam became a dominant issue. And by the 1970s, the long postwar growth wave was coming to an end. Still, the civil rights movement remains a striking example not just of progress long-deferred, but of the optimistic, even utopian, dimension of les trente glorieuses.

The vision was not fully realized, but major strides were made. Despite racial divisions that were strong and enduring, Congress passed major legislation to advance voting rights and racial equality. It should not be forgotten that support was bipartisan; Republicans made up for the resistance of Southern Democrats. The Johnson administration was able to introduce Medicare, Medicaid, major antipoverty and economic opportunity programs, support for both public transportation and motor vehicle safety, dramatic federal support for education, cities, and consumers, and such new organizations as the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.17 Public investments during les trente glorieuses provided specific services, but also sought to knit society together. Providing access to education served both goals. But perhaps the clearest demonstration of the second came in building infrastructure. In Europe, the project of rebuilding after the damage of World War II ensured that trains, postal delivery, and the electrical grid reach all (or nearly all) citizens. Nationalizing railroads was a central policy.

The United States also took on building new, better, and more democratically distributed infrastructure. Electrification was extended throughout the countryside by building on the New Deal success story of the Tennessee Valley Authority and supporting cooperative rather than only for-profit utilities. But the United States chose road building rather than strengthening its railroad system.

The Interstate Highway System, launched by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956, joined all the continental states (and I am sure mine was not the only family in the 1950s and 1960s to pack the kids into the station wagon every summer and set out eventually to visit all those states so the children would know their country). Road travel was supported by voluntary associations, such as auto clubs, and boosted motels, fast-food franchises, and similar businesses. It was complemented by an increase in the number of national parks—a system launched during the westward expansion that followed the Civil War. Public investment in roads and parks encouraged private investment in motels, gas stations, and above all cars. Connecting a large and geographically diverse country, it also encouraged a sense of public solidarity, as middle- and working-class Americans flocked to enjoy the different parts of the country. Of course, the sense of solidarity was grounded in compromise that helped to set up later crises. Cars brought dependence on fossil fuels that contributed to climate change, vulnerability to oil shocks, and indeed future wars and terrorism. Enriched by the auto boom, car and tire makers and oil companies lobbied against public transit systems. When rail transport was reorganized, it was into a disastrously bad system that left passenger rail perpetually underfunded, not least because it was separated from profitable freight services.

During the decades after the Second World War, both European and North American countries succeeded in providing dramatically improved housing to majorities of their populations (though substandard housing remained a mark of poverty). In Europe, the trend was for public housing and state support for private rental construction. In the United States, it was for private home purchases made possible by state-subsidized or guaranteed low-interest loans. Rental prices were controlled in some urban areas, but public housing remained exceptional, and mainly for the urban poor. White anxieties about racial integration exerted a strong influence.

Individual home ownership—which spread people out and made them dependent on cars—was a popular choice more than a policy imposed against resistance. Still, it was steered not just by zoning but by finance and government investment. US housing was organized into suburbs accessible mainly by cars, while in Europe, residential communities were better served by trains and buses. Policy choices blended with personal preferences and a culture prizing individual autonomy. In the United States, cars were at the center of the postwar boom.

The separation of residential from commercial areas was a mixed blessing from the point of view of sociability.18 Tracts of houses were developed to sell within narrow price ranges, maximizing homogeneity of circumstances. Many carried explicit prohibitions on selling to Blacks, Jews, and other excluded groups. The Supreme Court ruled against these in 1948 but provided no enforcement. This came only with the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Among other things, the act required removing racially restrictive covenants from deeds (a task I performed as part of a high school job in a title insurance company).

Suburbanization brought gains for individuals understood as consumers, though with environmental costs and reinforcement of social divisions. Increased geographic mobility reduced connection to local communities—more rapidly in America than Europe, but widely. Growing numbers of young people who went away to college didn’t return to their hometowns. Corporate executives were transferred among multiple locations. Economic opportunities beckoned people to urban and industrial areas. Even family changed. Fewer people lived in extended family groups, more in nuclear families of just parents and children. As more moved in search of economic opportunity, fewer lived near their relatives, though telephones allowed them to keep in touch. The average number of children in each family declined. The length of time parents lived without their children increased. And the nuclear family of the era came with a strong ideology of men working and women at home. As men worked away from home, often commuting some distance, women were increasingly isolated.

In short, even real gains had downsides. And some of the gains were slower or more limited than many hoped. Still, les trente glorieuses saw sustained growth, relative peace, and improved standards of living.

Social Democracy and Organized Capitalism

The compromise between capitalism and democracy also meant a compromise between pragmatism and possibilities for more radical improvement. Even in the Nordic countries that incorporated the most socialism into their compromises between democracy and capitalism, there was more focus on incremental improvement than sweeping change. Everywhere there was a compromise between maintaining established and inherited privilege and introducing more equality.

This new regime came only after the Great Depression, thirty years of world war, and a shift from British to American hegemony.19 It grew out of reconstruction after disaster. Still, it was a remarkable change. It was born of a meeting point among campaigns to improve society, business efforts to combine growth with stability, and governments committed to active pursuit of an enlarged conception of the public good. Growth helped make possible expanding welfare states, agreements between unions and employers, and better working conditions in a range of businesses. Newly inclusive politics brought wider participation in elections and pressure to use government to improve conditions throughout society. Parties explicitly representing workers played an increasingly central role. They campaigned not only for material benefits for workers but for broader political improvements and building of government institutions. In the United States, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 signified something similar. Culminating achievements of the New Deal, as well as of the civil rights movement, they could not have been passed without trade union support. This combined pursuit of economic justice and empowerment with democracy represented an American version of what Europeans called social democracy.

In many ways, les trente glorieuses was the great era of social democracy—not simply of parties with that name but of the project of pursuing political democracy and a better society together against the background of relative capitalist prosperity. But this depended also on receptivity in business and on the political right. Social democracy was mirrored by what has been called “organized capitalism.”20 This centered on the advantages to business of a close relationship with government and a more stable working relationship with labor. Workers in the advanced industrial societies were also central to expansion of consumerism.

Businesses were themselves settings for social relations as well as jobs and profits. Employment also brought a variety of secondary benefits including a sense of dignity and security to plan for the future. Industrial capitalism concentrated workers in cities and towns, and many companies supported the communities where their facilities were located. Companies were the distributors of benefits such as health care—not just voluntarily but as a result of labor negotiations. This is why later deindustrialization and radical emphasis on private property had such a brutal and destabilizing effect.

What I have just called “organized capitalism” is also sometimes called “Fordism” after the leading role the Ford Motor Company had played in the maturation of industrial society.21 Ford pioneered not just assembly lines and mass production, but vertical integration—bringing as many different parts of the production process as possible under the control of one company instead of leaving them all to different smaller businesses. Ford owned iron-ore mines and rubber plantations, freighter ships and a railroad; it made its own glass for car windows. This strategy enhanced Ford’s control and reduced its vulnerability to market competition.

At the societal level, Fordism meant a regime of cooperation among capital (companies, but also their investors and creditors), labor (represented by unions), and government. Capitalism continued to generate wealth—indeed, to grow it. The rich got richer. They just didn’t get richer as fast as they did in the early twentieth century or have since the 1970s, or quite as much at the expense of working and middle classes. Nor were there as many of the super-rich in proportion to the just pretty rich. This meant that the gap between the rich and other citizens could be reduced—which was good for democracy.

As part of the postwar compromise, governments invested directly in capitalist growth. They built infrastructure, educated skilled workers, and funded research crucial to the new high-tech industries and transformations of health care that took off from the 1970s. These brought wide consumer benefit and also a massive windfall for corporations and their financial backers. Government economic engagement was actually good for business. Government regulation helped stabilize capitalism itself. Regulations on lending practices, capital requirements for banks, and requirements that publicly traded companies honestly disclose their financial accounts were correctives to the kind of recklessness that had led to the Great Depression. Governments also acted to support business by providing insurance for banks and for mortgage lending. Regulations benefited workers by setting working hours and minimum wages. They also benefited consumers by setting product safety standards in areas such as food and drugs—and insisting that sleep wear for babies not be made of highly flammable materials, as it once had been.

This social democratic compromise included transfer payments from government and thus taxpayers to those judged needy. Children and the elderly were prime beneficiaries (and support for young children changed their whole lives). Transfer payments significantly reduced poverty, but they were not the center of the welfare state: this was provision of services like education or health care. Nor were they as important to reducing inequality as expanding opportunities for employment and social mobility. They were, however, crucial to security and stability.

So were policies and private sector agreements such as contracts between unions and employers, which brought workers (including middle-class office workers and professionals) a greater share of national income. Bargains between workers and employers produced other key elements of the larger compromise—safer working conditions, for example, an end to child labor, and limits on the working day—some of which were then reinforced by laws and regulations. These bargains derived from union strength. Unions were successful because after a century of looking the other way when employers blocked the formation of unions or had striking workers beaten and shot, governments eventually passed laws guaranteeing the right to organize and to fair conditions for bargaining. As important as specific material benefits or greater equality was the rich range of intermediate organizations to which workers and other citizens belonged.

Solidarity and social organization were not only benefits of social democracy, thus, but also crucial resources for achieving it. A social contract more beneficial to ordinary citizens was rooted partly in the solidarity forged in the war itself. Greater equality and a sense that government institutions must provide for the well-being of all citizens were ideas advanced in long struggles from the English Civil War to the American and French Revolutions through the growth of trade unions, labor and social democratic parties, the socialist movement, and Christian movements for social reform. Broader democratic participation was rooted in 150 years of campaigns for women’s rights, for religious freedom and inclusion, and for public health. And each of these social movements forged solidarity in addition to reshaping culture and thought and pursuing instrumental objectives.

Social democracy and organized capitalism brought a relatively good but temporary resolution to the double movement Karl Polanyi had described. They stabilized the chaotic dynamic of action and reaction initiated by disruption and dispossession during the Industrial Revolution. Social democratic compromises brought a combination of stability with growth, widespread prosperity, and care for those most in need. As noted at the start of Chapter 2, some were left out, and some were even pushed backward as others advanced. Nonetheless, equality and opportunity grew, and there was an increasingly optimistic sense of the future.22 Solidarity or social cohesion was also important and was grounded in a combination of local communities, states or provinces, and national institutions; in strong trade unions, civil society organizations, and the expansion of the middle class. Solidarity was as important as individual economic incentives to securing majority support for building tax-based public institutions to provide health care, education, old-age pensions, even high-quality television. It was important that citizens regarded these as provisions in which the whole society shared and that they regarded their fellow citizens as full members of that society.

The middle class grew in every developed country. The share of total national income that went to the richest 1 percent declined from the Great Depression and World War II until the late 1970s—when it started a rapid increase.23 Indeed, unionized manual workers often enjoyed sufficiently high wages and benefits that the boundary between “working class” and “middle class” became fuzzy. Not only could workers earn enough to support their families, but they enjoyed high levels of job security and could plan for their own old age and their children’s educations.

Of course, just as political inclusion of women, Black Americans, and immigrants took many decades and remained incomplete, so economic inclusion was unequal. Employers were biased, but even social democrats focused most on the needs of a relatively privileged subset of workers—mainly male, white, and national (that is, nonimmigrant but sometimes not even the children of immigrants). Others experienced less job security, lower wages, and often less dignity at work.24 The very idea of a “family wage” presumed male breadwinners—and idealized a kind of nuclear family that was more prevalent in the 1950s than today, but hardly universal. And, as discussed briefly in Chapter 2, opportunities such as the American GI Bill were often structured specifically for white men.

Greater fairness for racial and ethnic minorities, women, and others came slowly and was constantly resisted. Fatefully, this meant that some groups were durably excluded from full participation in the overall advance. Black Americans and women are the prime examples, but there were also other pockets of relative exclusion—famously Appalachia but also significant parts of the rural South.25 While many international immigrants found impressive opportunity in the United States, racial and ethnic bias was significant. Exploitation of migrant workers, notably Mexican farm laborers, was extreme.

Social democracy—considered a radical project before World War II—became a mainstream effort to use democratic governments to deliver more equal economic and social benefits. In Europe, specific political parties bore the name—such as the Social Democratic Party in Germany. But a much wider range of citizens took on the project of simultaneously extending democracy and building institutions that would sustain it. National health care, pension, childcare, and educational systems all produced wider sharing in the benefits of capitalist growth. They also supported greater participation in pursuit of the public good. And they were supported by Christian Democrats and even some Conservatives as well as parties officially called Social Democrats or indeed Socialists.

In the United States fear of the Left was stronger. Few spoke explicitly of social democracy (let alone socialism). Still, some of the kinds of institutions social democrats built in Europe were built in the United States with support from Democrats and sometimes liberal Republicans. The United States even led in some areas, such as education—though not in others, such as public health. The US version of social democracy relied on corporations to deliver many benefits, from health insurance to pensions. This meant that such benefits were not universal, as they were in Europe, and the role of political mobilization in securing them was less evident. Still, for a time, it did mean that there was growing security for most American workers. But reliance on corporations set up a crisis that would grow from the 1970s as employment in secure jobs with benefits declined sharply. Workers in the United States lost benefits faster than those in Europe.

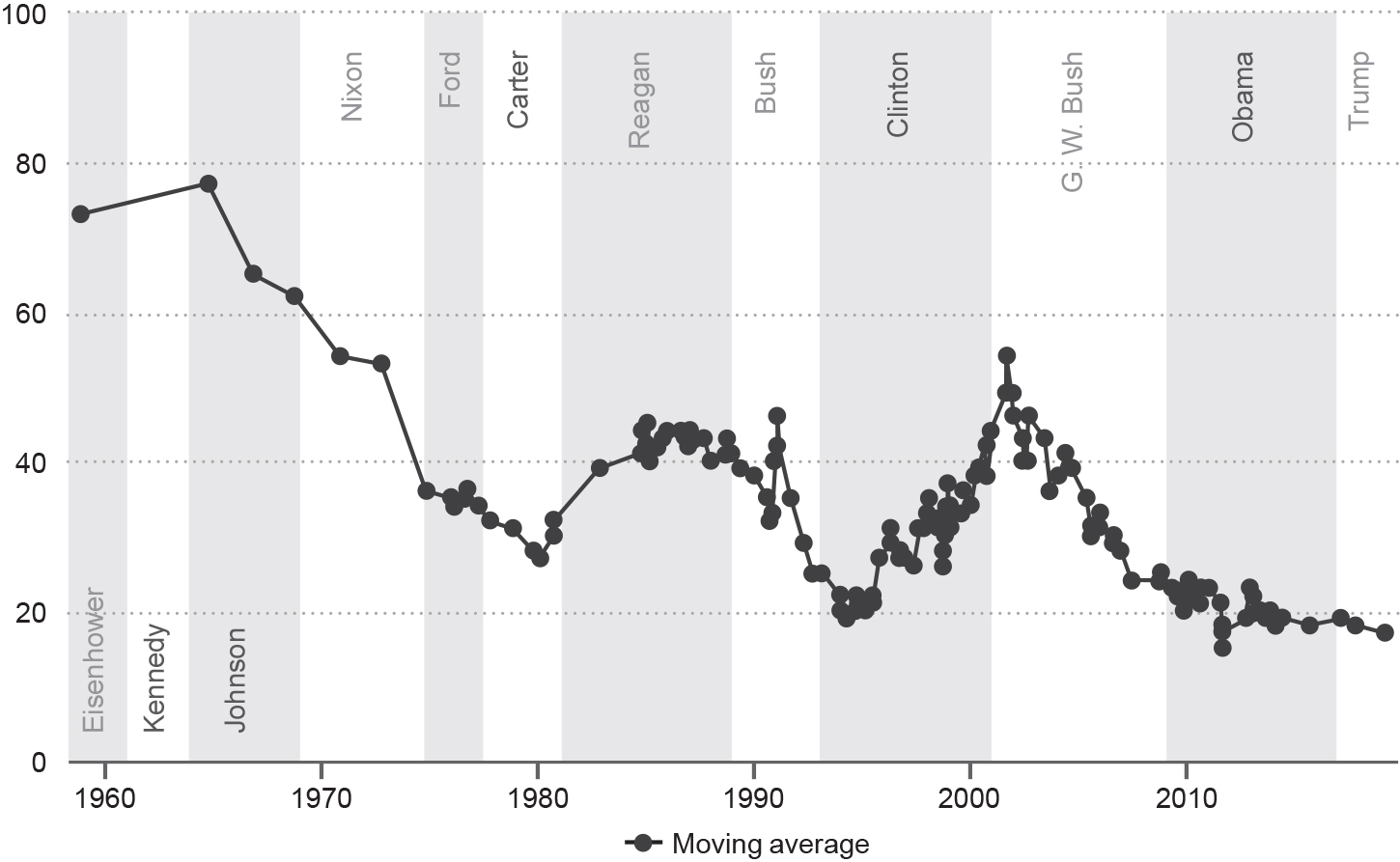

Figure 1. Americans’ declining trust in their government: percentage who trust the government in Washington all or most of the time

Pew Research Center, “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2021,” May 17, 2021.

The postwar achievement was to make the wellbeing of at least most citizens the object of government policies and institutions and to support this by more equitable sharing of costs and at least tacit but sometimes active business embrace of a more equal society. This was neither automatic nor just the result of top-down decisions by government leaders. It was the result of protracted struggle. Eventual cooperation was shaped both by recognition of social change and by a sense among the powerful that because of consumer markets and growth generally, higher pay and greater social benefits did not have to come directly at the expense of owners and managers. Before the postwar boom ended, however, confidence that it was delivering all it should began to erode. This is in many ways the story of the increasingly questioning 1960s. Did schools really bring opportunity to everyone? Did the benefits of government programs outweigh the frustrations of bureaucracy? Did churches deliver salvation or promote complacency? Was racial integration working? Our trust in each other and in institutions declined. Declining public confidence in government set in during the 1960s and has continued into the present. (See Figure 1, which presents a moving average of multiple polls.)26 Both twenty-first-century Trumpian anti-intellectualism and Britain’s secession from the EU in Brexit reflect disappointed optimism, but it is important to remember the hope and promise.

Three Catches

Democracy is always in part a promissory note from all citizens to each, offering assurance that everyone’s interests will matter in collective decisions. Not surprisingly, the glass of progress is seldom more than half full.

Perhaps paradoxically, the protests of the late 1960s grew from the very optimism of les trente glorieuses, the belief that a better society could and should be built. But they grew also from the discovery that some of the promises of the era were false or at least exaggerated. Western countries were still imperialist. Expansion of educational opportunities had not ended inherited inequality. Public debate remained constricted despite formal democracy. Prosperity alone did not make life satisfying.

These advances came with three catches that made the achievements of the welfare states feel less liberating by the 1960s and 1970s. We can name them after great social theorists who focused attention on the complexities and even paradoxes of democratic extension of state benefits in capitalist societies.

The first catch is the reliance of the welfare state on bureaucratic structures and the rationalization of social life. Let’s call this the Weber catch, after the German scholar Max Weber, who was clear a hundred years ago about the significance of scale (discussed in the previous chapter): “bureaucracy inevitably accompanies modern mass democracy, in contrast to the democratic self-government of small homogeneous units.”27 In all national versions, those who built welfare institutions as “second movement” responses to what had been disrupted by capitalist industrialization bet more on formal organizations and expertise than on decentralization and community engagement.

Genuinely important public benefits became sources of frustration when access to them was governed by bureaucracies that seemed too complex, too impersonal, too obsessed with rules, and too often ready to deny the benefits to those who made errors in their applications. From issuing drivers’ licenses to getting health care or pensions or paying taxes, bureaucracies gave government an unattractive face. Schools often seemed more about rules and compliance than about education. Hospitals seemed to have more forms than medicines. Of course, corporations could be bureaucratic, too, but bureaucracies came to dominate citizens’ experience of government.28

The second catch is that the delivery mechanisms of the welfare state turned out to be disciplinary. It’s not just in prisons, the military, or traffic control that modern states demand adherence to detailed rules and punish deviation. The state becomes disciplinary in regard to health, sexuality, and education. States offer welfare benefits only in exchange for participation in disciplinary regimes.29 Social workers visit homes to check up on recipients of benefits; even well-intentioned advice may carry an implication of criticism and may implicitly seek to discipline recipients into conformity with the cultural values of the bureaucrats.

Schooling focuses not just on manifest fields of knowledge, but also on a “hidden curriculum” of learning to arrive on time, sit still, turn in assignments promptly and neatly. These are all dimensions of discipline that correspond to demands of employers, especially in the growing sector of office work.30 Schools discipline children into conformity with gender roles. This has changed, but only recently and partially. In the 1950s, girls were commonly taught cooking and domestic skills—and boys were not. Even extracurricular activities such as sports or dances were settings for disciplined training in dominant binary gender role expectations.

Discipline remains implicit in many of the recent efforts of behavioral economists and policymakers to “nudge” citizens toward better health, more saving, or compliance with regulations.31 The nudge can easily shade into surveillance and control, not least as “big data” are mobilized to shape all manner of human behavior.32 Already in the 1960s, protesters at Berkeley repurposed the instruction “do not fold, spindle, or mutilate” into a protest against being reduced to a component of a bureaucratic system.33 We can call this the Foucault catch, after the French social and cultural historian and theorist, Michel Foucault.

The third catch is the tendency to perpetuate inequality in new and disguised forms. Let’s call this the Bourdieu catch, after the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who demonstrated how inequality could be reproduced in cultural distinctions and resources (cultural capital) that yielded the effect of inheritance even in nominally meritocratic or egalitarian societies.

Take education as an example. Before the 1930s, the chance to complete secondary school was rare even in the most developed countries, and college or university was available only to a tiny elite. Starting with responses to global depression in the 1930s and dramatically expanding in the 1950s and 1960s, access became much more widespread. This was good, but less egalitarian than it seemed. Students of different classes and races were educated in schools of very different quality and ambition. Differences in what families could offer their children in preparation for school and supplementary activities were enormous. These meant the playing field wasn’t level. But standardized tests and formally equivalent credentials disguised inequality. All universities granted bachelor’s degrees, for example, but these did not have the same meaning in job markets or social status. At the same time, the amount of formal education required for work at a given level of the economy increased. Jobs previously available to high school dropouts began to require university degrees. With this focus on more and more credentials, education became increasingly a sorting mechanism.34 Not least, the apparently equal access made it seem as though failure to get enough or good enough education was entirely a personal failing rather than of family resources or how the system worked.35

The Bourdieu catch is thus more than simply the fact of continuing inequality. It is the covert way in which social transformations, even mostly good ones, are constrained by reproduction of enduring inequalities. It is the enlistment of individuals in seemingly fair and shared projects for which they are very unequally prepared. This makes winners more sure they deserve rewards—and less humbly grateful—and leads others to blame themselves or be angry at institutions for lack of success (see Chapter 4). Not least, it is a sense of false promises. Even progressive social transformations that bring forward movement on some dimensions withhold it on others; steps forward for some come with blockages or disadvantages for others.

These three catches shaped discontents with welfare states that came to a head in the 1960s. Initially, the first two catches seemed more central. In the neoliberal era that followed the postwar boom, the third became more and more striking. The three catches were not inevitable. They motivated political efforts to deepen and improve democracy, protests to end specific abuses or problems, and a counterculture that for a time flourished in opposition to unequal, rationalized, and disciplinary society. This brought some lasting changes—notably in gender roles. Overall, though, the issues did not go away; many became more severe as inequality deepened after the 1970s. Pursuit of authenticity and personal expressive freedom dovetailed with an ideology of meritocracy that purported to make inequality fair. (See Chapter 4.)

All three catches to les trente glorieuses kept their force after that more optimistic era ended, and indeed were intensified in the new neoliberal era of massive privatization and loss of confidence in government. The 1960s and early 1970s were transitional. If les trente glorieuses failed to achieve as much equality as they promised, the neoliberal era that came after radically deepened inequality. It did so in part by saying “greed is glorious” but also by denigrating the public institutions leading efforts to ensure equality. Neoliberal reforms of government did not make it less bureaucratic, but they did sometimes starve institutions of resources, which, in turn, made bureaucracy all the more frustrating. Welfare reforms made at least parts of the system even more disciplinary, demanding work and policing of private life from those receiving social support. Meritocratic ideology intensified the Bourdieu catch (see Chapter 4).

Crisis

During the 1960s and early 1970s, a variety of social movements challenged the legitimacy of the institutional arrangements that had reconciled capitalism, democracy, and the Cold War in wealthy Western countries. From civil rights to labor to peace and the environment, activists held that democracies could do better. Efforts to expand participation in democratic politics grew increasingly prominent. Public support for international conflicts, and the Cold War and imperialism behind them, began to fade. The conflicts symbolized by the year 1968 combined calls for peace with demands for greater equality, refusal of capitalist demands for growth, and rebellion against cultural conformity. Institutionally structured compromises crucial to les trente glorieuses came under pressure across a range of scales from personal psychology through national politics to global political economy.

As often, crisis came with a perfect storm of causes, many internally related. Some were cultural, even “countercultural,” as students and others at once challenged some of the ideals of postwar culture and demanded that societies do a better job of living up to their professed ideals. There was rejection of tacit limits to the vaunted freedoms of democratic society. There were demands to overcome the blockages on opportunities for Black Americans, American Indians, women, and others.36 There was growing recognition of the environmental damage brought by the commitment to economic growth that underpinned the postwar compromise between democracy and capitalism.

As important as the cultural and political movements of the 1960s were, it was in 1973–1975 that les trente glorieuses came to an end with a jolt. Rebuilding after World War II, government investment, and commercialization of new technologies had underwritten a massive secular boom. In the 1970s, this long period of stable growth abruptly gave way.

Acting on the promises of equality and opportunity, workers demanded higher wages and benefits; women and minorities demanded inclusion. Memories of the Great Depression and World War faded while taxes remained high and profits at best stable. Expansion of markets ceased to compensate for declines in profit rates. At the same time, new technologies began to challenge established industries. The tacit bargain between capitalism and social democracy grew increasingly stressed.

In 1971, President Richard Nixon responded to growing inflation by freezing wages, placing surcharges on imports, and unilaterally canceling the international convertibility of the US dollar to gold. From a US perspective, European and Japanese economies had grown from clients into increasingly effective competitors. Expansion in the “developing” world confronted increasing pressure from governments and movements seeking a greater share in the proceeds. There were revolutions, failed revolutions, and national independence movements. At the same time, the Vietnam War grew more expensive—partly because it expanded, contrary to leaders’ recurrent promises that it was nearly at an end, and partly because of deployment of more expensive weapons. As it became more controversial, the government shifted from ground to air combat and also to financing the war by bond issues rather than taxes.

Then, in 1973, Israel defeated neighboring Arab states in the Yom Kippur War. In response, Arab leaders turned the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) from a sleeping talking shop into a formidable cartel. They restricted production and drove up prices. Ordinary motorists faced gas shortages in Europe and especially the United States; heating fuel was in short supply as a cold winter came on. Industry either slowed or paid much more for energy. All this brought the deepest economic recession between the Great Depression and the financial crisis of 2008–2009.

If the 1960s were years of exaggerated voluntarism when a counterculture imagined reshaped the world by almost unilaterally remaking culture, the 1970s brought home the message that choices were limited. The crisis was among other things a demonstration of the power of a larger “system” in which finance, oil supply, job markets, and inflation were all connected. It produced a fundamental shift of direction for the developed democracies. At its center were (a) a new ideology claiming that private property was sacred, public alternatives were illegitimate, and market efficiency should be the goal of all economic activity, (b) a restructuring of capitalism that gave less centrality to the production of material goods and dramatically more to finance and global trade, and (c) a dramatic reminder of the dependence of the developed democracies on fossil fuel and the countries that exported it.

Neoliberalism

The most influential economic ideology of the last fifty years, neoliberalism, has given its name to the whole period and policy approach. Its roots lay in the 1930s, and it had been gaining followers for decades. But it got a jump start by shaping policy in Chile after the military staged a coup against the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. The general who took charge, Augusto Pinochet, relied heavily on a group of economists trained under leading neoliberals at the University of Chicago (and they on their old professors). By 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister of the UK on a neoliberal platform, and as president of the United States from 1980, Ronald Reagan helped make neoliberalism dominant, rather than only an aspect of economic policy.

We should recognize that the term “neoliberal” masks complexity.37 Not all neoliberals thought exactly the same things—though they had a formidable apparatus for developing and maintaining a party line. Neoliberal ideals shifted and developed over time and were given different emphases in different practical contexts. Both adherents and critics often reduced neoliberalism to a caricature; more than once some said it was over and some that it had never existed.38

Much of the reasoning core to neoliberalism was shared with a wider range of economists, though some features were given special emphasis (especially those linked to individual freedom and private property) and some lines of thought were anathema (especially those dubbed “collectivist”). The rise of neoliberalism came partly because economics moved to center stage, and economic considerations dominated public policy from the 1970s until at least the financial crisis of 2008.39 Though grounded in economics and political philosophy, neoliberalism was equally a political movement.

Neoliberalism signaled basic commitments to private property and minimalist government. This dovetailed with a long-standing conservative objection that big government was expensive. But it placed much more central emphasis on the fear that any government beyond the most minimal was a threat to liberty. This is the theme of Friedrich Hayek’s foundational book, The Road to Serfdom (1944), composed with Nazism an especially looming presence but focused on the threat of socialism. The UK and United States, Hayek suggested, seemed to be abandoning “that freedom in economic affairs without which personal and political freedom has never existed in the past.”40

Neoliberalism was literally liberal, not conservative in the traditional sense. It was not about saving the best of an old order, but about a radical conviction that private property is the necessary basis of liberty as well as wealth. This made it compatible with considerable social liberalism. Many neoliberals even thought of themselves as libertarian. They favored legalization of marijuana and ending restrictions on homosexuals. It became common to say, “I am socially liberal but economically conservative.” But where “conservatism” meant neoliberalism and its market fundamentalism, it lost touch with older conservative traditions. It supported capitalism and private property, but not the longtime conservative goal of saving communities.

Believing that markets would always produce the most just and freedom-promoting outcomes, neoliberals opposed restrictions. Most recognized that some minimal collective needs, such as national security, might be provided on nonmarket bases. Otherwise, they were “market fundamentalists.” They supported privatization and marketization of health care, education, old-age care, the building and operation of infrastructure, and nearly everything else. Though Hayek himself argued that it made sense to pursue universal health care even by means of government action, later neoliberals, especially in the United States, did not follow his lead. The more extreme among them opposed minimum wage laws and the existence of a government agency to protect the environment. Many even believed that the government should play little or no role in setting standards for food purity, say, or pharmaceutical safety.41

Market fundamentalism also made neoliberals oppose restrictions on capital flows, tariffs, and attempts to protect national economies from international market competition. They were avid proponents of free trade. With Margaret Thatcher, they said “there is no alternative” to global competition. Thatcher repeated the phrase and its acronym, “TINA,” over and again. Her statement was close to a paraphrase of Herbert Spencer and echoed a long history of insisting that much of economic policy should be seen as a matter of necessity rather than choice. This invited the rejoinder “another world is possible.” It also amounted to excluding democracy from the realm of economics.

Underpinning the specific political and economic claims of neoliberalism was the notion that government should not take on “substantive” agendas such as improving society. Instead it should defend the “process” rooted in markets and private property. Hayek argued this centrally on the basis of maximizing individual freedom; to pursue the collective good, government would have to take property from individuals, reducing their freedom to use it. In addition, Hayek and later neoliberals argued that markets based on private property would do a better job of securing the good than planned action by governments. Markets would be more efficient. Even a democratic government should not interfere with market self-governance.

Hayek and most neoliberal economists did recognize that there would be some “market failures”—occasions when rational individual choices would not add up to rational collective outcomes. But they contended that markets were by far the best mechanisms for discovering inefficiencies—and that removing these inefficiencies was the best path to improvement. The neoliberal presumption is that in most cases, government intervention to solve market failures will actually produce worse outcomes—because of bureaucracy, values in conflict with efficiency, or inadequate foresight. The preferred neoliberal solution is almost always to let competitive markets work. Barriers to competition—such as tariffs or subsidies—must be removed. It is on this basis that politicians influenced by neoliberalism have sought since the 1970s to reduce government provision of housing, welfare payments, or postal services. They have seen these only as restrictions on free market competition.

More extreme neoliberals objected even to minimum wage laws—which offer something of an index of what the neoliberal era has meant for workers. The federal minimum wage was launched as part of the New Deal. Periodically adjusted, its value peaked in 1968. Since then, it has risen more slowly than the cost of living, the average wage, or economic productivity. If it had in fact tracked productivity, it would be $24 as of 2021.42 By this standard, President Joe Biden’s 2021 proposal to raise the minimum wage to $15 was moderate, and the prevailing reality of $7.25 per hour was shockingly low. Of course, many factors besides just productivity go into determining wages. And while there has been inflation in many components of the cost of living, there has been deflation in a few, and even low-wage workers today benefit from goods that were nonexistent in 1968—for instance, cell phones. But the point here is not to debate precisely what the minimum wage should be, but to show how neoliberal thought translated into practical policies.43 These favored returns to assets over compensation for work.

Neoliberals regarded workers as simply a special interest and thus treated labor unions as restraints on free markets. Ironically—or perhaps simply contradictorily—most neoliberals did not see either corporations or concentrations of wealth in investment funds as comparable problems for free-market competition. Their abstract models of the economy simply assumed individuals as the basic actors.

Corporations

Neoliberals claimed Adam Smith as an iconic forebear and embraced the notion of a laissez-faire approach to the economy. Smith, however, saw relative equality as a condition for the “invisible hand” to work by conditioning the behavior of all market participants. For this reason, he objected to “combinations” of capital—that is, modern corporations—as well as of labor.44 Neoliberals followed only half their great ancestor’s prescription. For the most part, they ignored the asymmetry between modern corporations and human individuals.45

While the importance of corporations to contemporary economic and social organization is hard to miss, it is unclear both in theory and broader public discussion just what a corporation is. One long-standing legal theory sees corporations as created by delegation of power from states, as suggested historically by the governmental grants of corporate “charters”—not least to the companies that established the British North American colonies that became the United States.46

Neoliberals, by contrast, more often regarded corporations as a form of property structured by contract among individual owners. But this form of property is itself dependent on law for its structure and economic viability. Investors in corporations are protected by limited liability for any actions the corporation may take. This allows more or less impersonal large-scale markets in shares—by contrast to partnerships among investors known to each other. Limited liability establishes the corporation as a special sort of being. In a pivotal US Supreme Court opinion in 1819, Justice Marshall described a corporation as “an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law … with no soul to damn or body to kick.”47 Building on this, corporations are sometimes treated as a kind of person. In the 2010 Citizens United case, the Supreme Court held that corporations enjoyed First Amendment rights like those of human citizens—in that case, the right to make political donations as a matter of free speech.

Delegation of power is the perspective of a state; formation by contract is the founders’ view of a corporation. To an investor, limited liability is crucial. This is basically the guarantee that investors can’t lose more money than they invest. It is a legal provision that the contract of shared ownership does not extend to shared responsibility for damage the corporation may do. If the firm creates unsafe working conditions or harmful products, the investors (usually) cannot be sued. To a manager, a corporation is a hierarchical organization with rules, a power structure, and perhaps even a culture.

Whichever rationale is claimed, there is a basic asymmetry between corporations and “natural” human beings—since, among other things, corporations don’t have natural life spans and can be much larger, more powerful, and wealthier than humans.48 As I suggested in Chapter 2, this asymmetry (along with quasi-automated systems) is a major challenge to the condition of equality among discrete individuals presumed by Adam Smith and carried forward into neoliberal thinking.

As long as corporations are seen merely as devices for exercise of the powers of their owners, they fit well into the mainstream of neoliberal thought. But when it is recognized that they are organized to wield power, not just to pursue market efficiency, the alignment comes undone. Corporations are bureaucracies and hierarchies internally, and they take advantage of their asymmetrical clout to influence and often dominate other stakeholders, from employees to communities to suppliers and customers. But, by and large, neoliberals have embraced corporations, even lacking a fully coherent account of just what corporations are and why they are legitimate.

Milton Friedman took an extreme view. Corporations were created to manage the investments of shareholders, he wrote, and therefore should be run solely to enhance “shareholder value”—not to serve other stakeholders such as employees, customers, or the communities where they worked. “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”49 If they wanted, investors could use their shares of these profits for charity or to make a better society, but neither the corporation nor the government should make that decision for them. They should be allowed to choose only private benefit and ignore public good.

Friedman did not see inequality as an economic problem; in fact, he saw some level of inequality as desirable, mostly for motivational reasons. He argued in favor of poverty reduction, calling for a negative income tax as a way to provide basic resources to the poor. But he suggested this on the basis of compassion, not because he thought inequality was wrong.50 The basic economic principle for the distribution of incomes should be “to each according to what he and the instruments he owns produces.”51

In the context of deindustrialization, neoliberal doctrines suggested that states should not help workers. That would mean taxing wealth to pursue a “substantive” agenda. Even if this agenda involved the public good, that should not be a government choice, but a choice of the private beneficiaries of corporate profits (who alas did not step up much). Likewise, beyond what was necessary for smooth business transitions, corporations should not help workers who lose their jobs because this would be a misappropriation of the property of investors.

Moreover, neoliberal arguments suggested that helping fellow citizens was less likely to produce the public good than simply letting market forces work. Help to workers in the places where they lived might, for example, discourage them from moving elsewhere to find work. The situation from the 1970s to today has basically followed neoliberal lines: fading state action and reluctant corporate action at best. This did not stem just from neoliberal ideology, of course, but also from the pressures of financial markets. Action to help workers make decent transitions would appear as a cost on corporate balance sheets.

Other ways to think about corporate responsibility are possible. There has recently been a renewal, for example, of arguments for “stakeholder capitalism.” The notion is simply that firms should be responsible to multiple stakeholders. Investors are one class, but also important are workers; counterpart firms such as suppliers, clients, and financial institutions; and the communities (and countries) in which firms operate. Some argue that humanity at large or even the planet should be on the stakeholder list in the face of climate change and similar threats. In settings such as the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, arguments are made that this amounts to enlightened self-interest for corporations: is the morally right way to think and also economically wise because otherwise the door will be opened to less desirable forms of government intervention.52

Whether for self-interest or the public good, it is clearly good for firms to respect the interests of other stakeholders beyond shareholders. This is important because corporations are central institutions in the contemporary world. They shape economies too much, employ too many people, and deploy too much wealth to be left on the sidelines by theories of democracy. It is vital to find ways to make them positive contributors to the public good. Indeed, there is great variation in the extent to which corporations work in positive ways. This suggests that it is a mistake simply to condemn corporations wholesale and that it is important to find ways to improve them and their impact.

Corporate social responsibility is sometimes conceptualized mainly as charity, as using some share of profits for public purposes. It can be good to support orchestras or schools in this way. But much more fundamentally, corporate responsibility involves the ways in which corporations do business. Do they operate with honesty and transparency, with care for the environment and good wages for their employees, with commitment to the communities in which they work? Or do they hide their finances, allow corrupt practices, try by any means to block unions, pollute when it is convenient, and seek to dodge taxes by questionable accounting or manipulating international reporting? Do they use outsourcing simply to avoid paying workers better? Is chasing cheaper labor abroad simply a way to avoid paying fairer wages “at home”? Do they seek suppliers that also work with high ethical standards? Are they willing to buy goods produced by forced labor, even imprisoned populations of ethnic minorities such as the Uighur in China?

Indeed, to what extent do corporations recognize that they have homes? They work in local communities and in countries. But they also devise a variety of ways not to be bound by membership in either. The Citizens United case in which the US Supreme Court affirmed that corporations enjoyed First Amendment rights was curious not only for treating them as persons but for treating them simplistically as citizens—thus ignoring the extent to which they operate transnationally, avoiding taxes and laws that constrain human citizens much more.

Voluntary actions based on stakeholder capitalism can bring improvements on every dimension. But the extent of improvements is likely to be limited. Managers will often choose what is expedient. Managers make choices faced with competition from other firms. They can’t simply increase their costs relative to competitors and easily stay in business. As basic are pressures from financial equity markets with very short time horizons. Voluntary action cannot substitute for government failure to regulate.

It is far from obvious that protecting or nurturing the social conditions of democracy should be left to the beneficence of investors or corporate managers. Government has a key responsibility and a distinctive capacity to ensure conditions for democracy. It can shape whether and how much corporations contribute to the public good. Taxation and redistribution are important. Corporations could, for example, pay for a greater share of the schools that educate their future workers. Laws and enforcement could prevent tax avoidance. Regulations are vital, whether to ensure fair labor practices or appropriate management of social media abuses. Regulations can, in fact, help companies that want to contribute to the public good by ensuring that they are not undercut by competitors who do not share their public values.

The last fifty years are rightly called the neoliberal era partly because they are marked by government retreat from regulating economic activity. In the United States especially, but not only in the United States, laws that had long ensured greater stability, honesty, and transparency in business practices have been repealed without real replacement. This has enabled firms to generate more wealth for investors (their sole purpose, according to neoliberalism). Sometimes as a happy byproduct they have contributed to general prosperity, but more basically their flourishing has accompanied a division between skyrocketing stock prices and a much more troubled real economy. Bankruptcies have also skyrocketed.

There are three issues here. First, deregulation and finance-led wealth creation have made economies more volatile and risky. From the New Deal through postwar organized capitalism, stability had been an important goal alongside growth. This was an important condition for democracy. It gave citizens more chance to organize their own lives, both individually and in communities. It allowed participation in government agendas focused on improvement rather than emergency management.

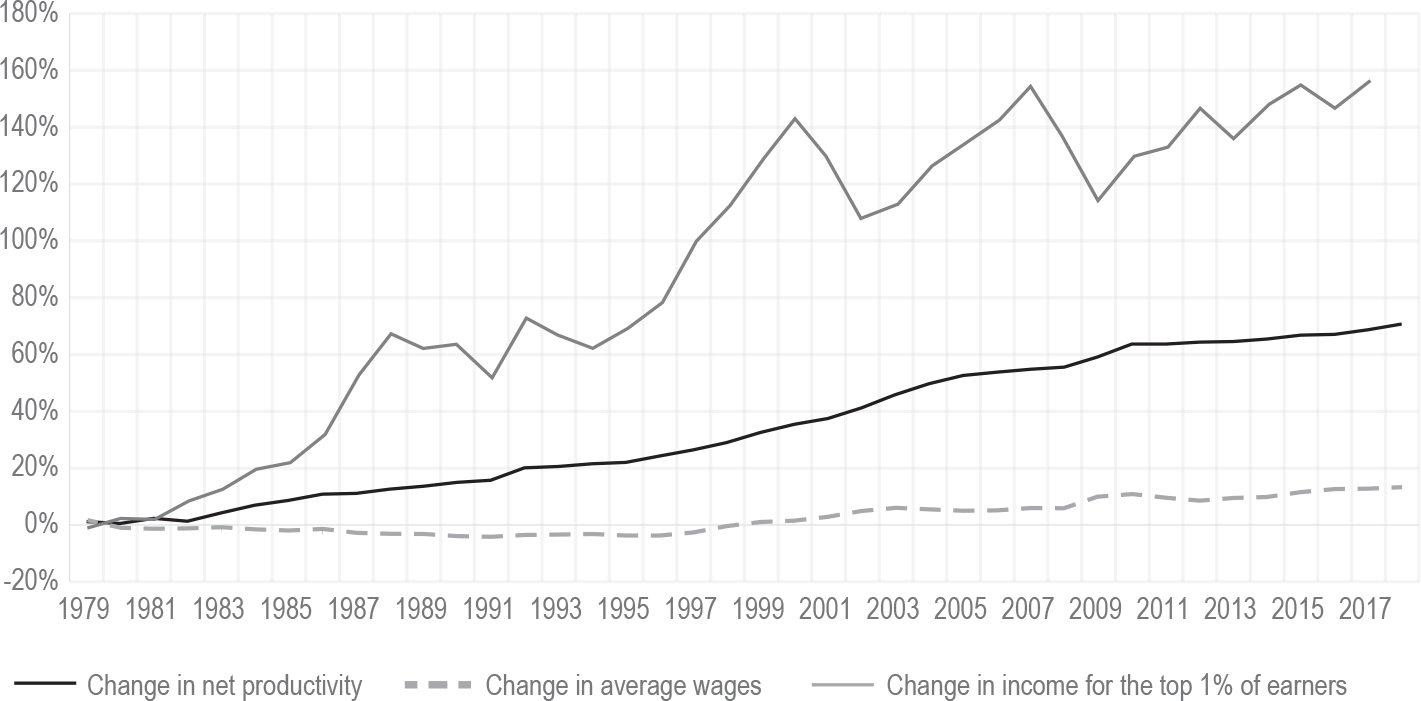

Second, the wealth corporations created has been appropriated mainly by investors and a few highly compensated managers. For most workers, wages have remained stagnant, as shown in Figure 2.

Neoliberalism has produced an economic system in which profits have been shared much less widely than had been the case during the organized capitalism of the postwar era. But democracy depends not just on total amounts of wealth, but how it is distributed.

Third, neoliberal capitalism has created not just enormous wealth but massive “illth.”53 Statistics such as gross national product (GNP) or gross domestic product (GDP) measure how much value is added in an economy. They do not measure the damage to the environment, death and disease from unsafe consumer products or breathing polluted air, or displacement of workers without adequate compensation. Illth is, in short, the negative side of wealth, the bad stuff created by the same economic activity. In the neoliberal era, wealth has been accumulated by an ever-narrower and more exclusive upper class—call it the top 1 percent. But illth has been more widely shared. Illth has created costs for governments as they tried, for example, to clean up environmental problems. Illth has been a problem for citizens at large and communities everywhere. But the burden of illth has been greatest for those who live nearest to the bad stuff or have jobs in the least healthy workplaces. In the United States, the human cost has been born especially by Black Americans, American Indians, Hispanic populations and immigrants, and by those in some specific regions who could not avoid the stench of meat-processing plants or the cancers linked to toxic waste. This is a basic challenge to democratic equality.

Figure 2. Change in productivity and income since 1979

Data sources: Lawrence Mishel and Julia Wolfe, “Top 1.0 Percent Reaches Highest Wages Ever—Up 157 Percent since 1979,” Economic Policy Institute, October 18, 2018; Josh Bivens, Ellis Gould, Lawrence Mishel, and Heidi Shierholz, “Raising America’s Pay,” Economic Policy Institute, June 4, 2014, updated May 2021 as “The Productivity–Pay Gap.”

Externalities

From the point of view of individual businesses, these ill effects are all “externalities.” That is, they do not appear on the balance sheets of firms—unless governments intervene to demand that firms pay, for example, for the cleanup of environmental damage. One of the basic features of modern capitalism, especially pronounced in the neoliberal era, has been that firms have enormous capacity to externalize the damages they cause.

Externalization of costs—both financial and human—has been basic to the deindustrialization and broader economic transformations of the neoliberal era. When factories close, neoliberals oppose public subsidies to maintain services. When communities collapse, they say to let them go. If workers need jobs, they should just move to wherever the jobs were even if it means starting over with few resources. And if there aren’t any good jobs, unemployment benefits should be kept to a minimum (perhaps the minimum for subsistence, perhaps the minimum necessary to avoid social unrest) so that workers will take whatever jobs are offered at whatever wages employers wanted to pay.

The overwhelming neoliberal focus on property rights has severely devalued community and social relations. It aligns with a view that individuals should be compensated for their work to the extent that the market values it and no more. All other economic rights belong to investable capital, against the claims of workers for better treatment or the right to form unions, claims for the environment or racial justice, or more generally to balance the freedom of property against other understandings of the good. In effect, neoliberalism defines the public good as maximal freedom combined with maximal capital appreciation. Placing no value on social cohesion or association, except insofar as it advances the interests of property owners, neoliberalism has undermined the solidarity on which democracy depends.

Like classical conservatives, neoliberals favor a minimal state. But the conservative tradition since its great pioneer Edmund Burke was not simply individualistic; it insisted that community and social institutions were crucial. Devaluing these, neoliberalism has left only markets. But markets are a weak basis for mutual commitment among citizens. Indeed, since market fundamentalism has dovetailed with the pursuit of frictionless globalization, it has offered no basis for citizens to value their country or their fellow citizens in particular.

Because neoliberals do not believe in a broader idea of the public good, they see promoting and securing economic liberty to be the fundamental purpose of politics. Most have rejected the previously dominant Keynesian view that strong governments should exercise their power to guide the economy and achieve social welfare. Of course, neoliberal economists vary in where they see legitimate exceptions to that rule. Some have even joined in efforts to design better government policies—say, to protect the environment. But more orthodox neoliberal ideology has been very influential (and helped to legitimate policy commitments that derived less from economics than from the self-interests of various business and political actors). Because of its overwhelming emphasis on private property and hostility to collective action, neoliberalism is not simply the radical defense of freedom its backers claim it to be.

Though neoliberal ideology calls for less government, neoliberal policies have been largely implemented by governments. They included selling off state assets such as railroads (not always in ways that preserved ideals of public service, and often at prices that gave investors bargains), charging user fees for access to public parks that were previously available free, and making educational policies that favor private schools over public. Despite individualistic rhetoric, the main beneficiaries have been large corporations and investors.

Moreover, while neoliberalism seeks less regulation, it has actually created new demands on government. Corporations have pressed governments to use the right of eminent domain, for example, to take land for highways and airports. They have not left this to the market alone for that would have increased the costs of the projects they favored. More generally, capitalist firms have depended on government picking up many of the costs they have treated as externalities.

Financialization

The mid-1970s crises were not resolved within the terms of the compromise that had governed capitalist democracies for the previous thirty years. In place of the Fordist pursuit of an institutionally organized, managed capitalism, “neoliberalism” brought attacks on taxes, regulation, government programs, and unions—all in the name of greater individual freedom.54 It also helped bring a dramatic shift from emphasizing industry to emphasizing finance.55

The change was in a sense announced in policy responses to the “stagflation” the followed the 1973–1975 economic crisis. Workers and capitalists agreed that a stagnant economy was a problem. But they differed on whether to prioritize fighting inflation or protecting jobs. The Federal Reserve Bank took a clear stand. It put all its effort into bringing inflation down, even though this meant employment and wage levels would suffer as they did for years after.56 The bank sided with capital not labor. But it sided especially with finance capital.57 Industrialists, after all, needed to make and sell goods—and in the course of that created jobs. Those bothered most by inflation were those who owned debt.