CHAPTER 17

THE FOOD AND AG INDUSTRY: THE BIGGEST CONTRIBUTOR TO CLIMATE CHANGE

When you hold an apple (or anything you eat) in your hand, you are connected to a global climate system. The tree that produced the apple takes in carbon dioxide, sunlight, and water to create the fruit. The nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, the truck that transported the apple, and the refrigerator that kept it cool all emit greenhouse gases (GHGs), which trap heat in our atmosphere. Human agriculture is able to exist because of a balance in the carbon cycle. The problem is that the world is heading toward a dangerous destabilization of this balance with carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide reaching concerning levels.

We may not realize that the corn-sweetened soda we drink, the juicy cheeseburgers raised on factory farms, the chicken breast sandwiches from giant poultry factories, or our GMO soy-based burger drive climate change in a way that is completely unsustainable. Our food system as a whole is the biggest contributor to climate change, even more than the energy sector. And in turn, climate change is threatening the future of food production. Reimagining how we grow, produce, consume, and waste food is the number one solution to reversing climate change. The good news is that it is not too late, but to understand why fixing our food system is so critical to our survival, we have to brace ourselves and focus on the bad news first. Yes, fixing our food system will make us healthier; result in economic abundance; help our kids learn better; improve our nation’s mental health; reduce poverty, violence, and social injustice; and even improve national security. And, yes, it will help us conserve our limited water resources, restore healthy soils, and make working conditions better for farmers and food workers, but none of that really matters if we become extinct. And that, my friends, is what most climate scientists believe is happening. The sixth extinction. NASA scientist James Hansen estimates that the amount of heat released into the atmosphere is the equivalent of atomic bombs the size of the one dropped on Hiroshima going off 400,000 times every single day, or about five every second.1 That is what is happening right now, even if it doesn’t seem that way. Understanding how food, agriculture, and climate are all linked may be daunting and depressing, but it is also ultimately hopeful. Many scientists, governments, international agencies, business innovators, agricultural and climate visionaries, and activists understand the intersection of these problems and are building solutions on multiple fronts. And we can all be a part of that with our choices, our voices, and our votes.

IS CLIMATE CHANGE REALLY THAT BAD?

The speed of change of our climate is increasingly evident. Octopi are found in strip mall parking lots as Miami floods. In 2019, we had 500 tornadoes in thirty days, flooding agricultural lands in the Midwest and impacting the ability of the Farm Belt to grow our food. We have once-in-500,000-years rains in Houston. In the Arctic, ice melt is destroying habitat for polar bears and raising sea levels. In May 2019, the global level of carbon dioxide crossed the threshold of 415 parts per million (each part per million equates to 2 billion tons of carbon). The last time Earth saw this level of carbon in the atmosphere (about 800,000 years ago) humans didn’t exist and oceans were 100 feet higher, there were hippos swimming in swamps that have become London’s Thames River, and trees grew in the South Pole.2 We’re already experiencing the crop failures, droughts, floods, heat waves, and extreme weather associated with climate change.

In David Wallace-Wells’s book The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming, the first sentence is, “It’s worse, much worse than you think.” His New York magazine article of the same title laid out the threats in bold relief.3 Hold your nose. This is hard medicine to swallow. But ignoring it won’t make it go away. And facing it just might herald our redemption from extinction at worst, or catastrophic disaster at best.

Fifty percent of GHGs now in the atmosphere have been released by humans in the last 25 years, and the rate is accelerating. If GHG emissions continue to rise at current levels, we can expect temperatures to rise up to 4 degrees Celsius or more, and extreme weather to intensify and damage life, infrastructure, and our food system.4 It may feel like slow change, but we will soon pay the price if we don’t reverse the trends. Within 20 years, temperatures are likely to rise more than 2 degrees Celsius. What does that world look like? The polar ice would significantly melt in the summers; coral reefs (on which we depend for our fisheries, which feed 500 million people) would disappear; extreme heat would make much of the South uninhabitable. Severe water scarcity would threaten more than 400 million in urban areas. Rising seas would wipe out island nations and coastal communities. Tropical diseases would migrate north, with 5.2 billion at risk for malaria. Air would increasingly become unbreathable, as it was in China in 2013, when melting arctic ice changed weather patterns, increasing pollution, which led to one-third of deaths that summer. Violence and wars would increase. We would have at least 100 million climate refugees, destabilizing countries around the world. Food would become scarce, with crop failures from heat, drought, and floods. We may need to grow crops at the North Pole rather than North Dakota. Global economies would be threatened by projected costs of more than $50 trillion.

According to the October 2018 report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change5 we must keep warming to just 1.5 degrees, so that means we have only 12 years to cut our emissions in half and 30 years to cut them to zero. According to the IPCC report, to achieve that, governments would have to radically transform the global economy, energy system, and food systems in ways that do not seem politically likely. Nearly all the countries that signed the Paris Accord are not meeting their pledges to reduce emissions.

“There is no status quo. Change is coming one way or another,” climate scientist Dr. Kate Marvel says. “But the fact we understand what’s causing climate change gives us power. We can choose the change we experience.”6 The biggest offenders? Farms and food waste. Fixing our food system on the front and back ends is one of the most effective ways to improve our changing climate. Even if we reduce our fossil-fuel use in the near future to zero through electric cars and more solar and wind power, the expansion of CAFO meat production and conventional agriculture with the loss of soil organic matter and soil erosion and ongoing deforestation could still produce enough GHG emissions to raise global warming by 2 degrees Celsius, the level the UN IPCC considers catastrophic.7

There is a slim possibility that new technology such as carbon capture machines can help. This suits the fossil-fuel industry and investors because they assume it means we can still pollute and just “capture the carbon,” and because it requires huge investment and infrastructure and can be very profitable. The scale needed and costs of this technology are staggering; the technology’s ability to draw down enough carbon is unproven; and even if it works it will not fix deforestation, desertification, draining of wetlands, soil loss, or the water cycle, which requires plants to create rain, or restore ecosystems. There is only one thing than can draw down enough carbon fast enough to matter: soil. No sector has more power to reverse global warming and climate catastrophe than our food system. It is the only solution that doesn’t just reduce emissions, but also sequesters carbon from the environment through the ancient technologies of soil, plants, and animals.

And while we need to convert to renewable energy, it will not save us. In fact, the only thing that can save us is the Earth itself—and rapid conversion of our current extractive, destructive food and agriculture system to a regenerative one.

INDUSTRIAL FARMS: MASSIVE PLAYERS IN CLIMATE CHANGE

Industrial agriculture contributes to climate change through the overproduction of the three main GHGs: methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide. Here’s how:

Carbon dioxide gets released from the soil through tilling the land (causing loss of organic matter) and through deforestation to grow soy and corn for CAFOs. The world’s soils contain three times the carbon contained in the entire atmosphere and can suck up a lot more.

Carbon dioxide gets released from the soil through tilling the land (causing loss of organic matter) and through deforestation to grow soy and corn for CAFOs. The world’s soils contain three times the carbon contained in the entire atmosphere and can suck up a lot more.

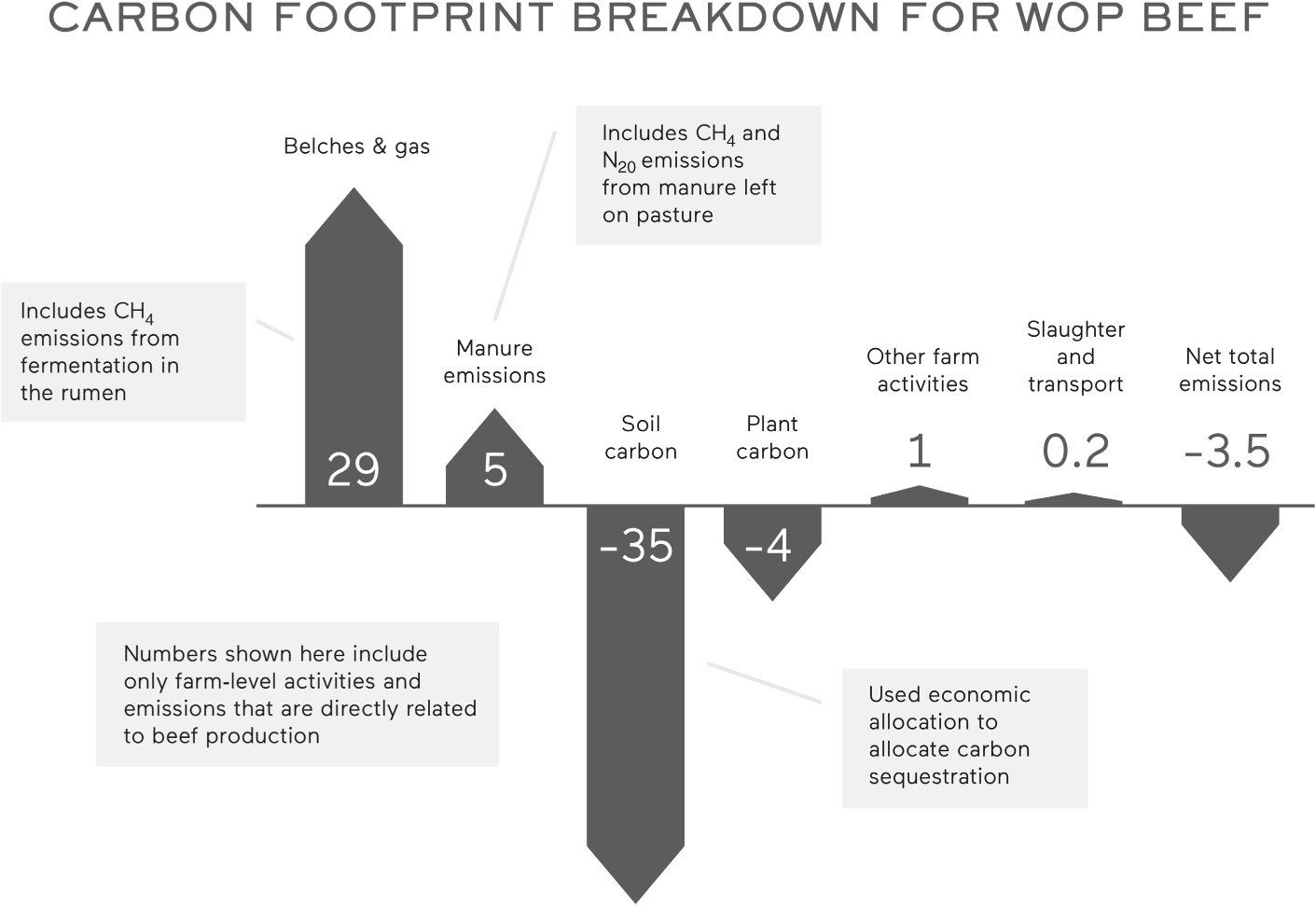

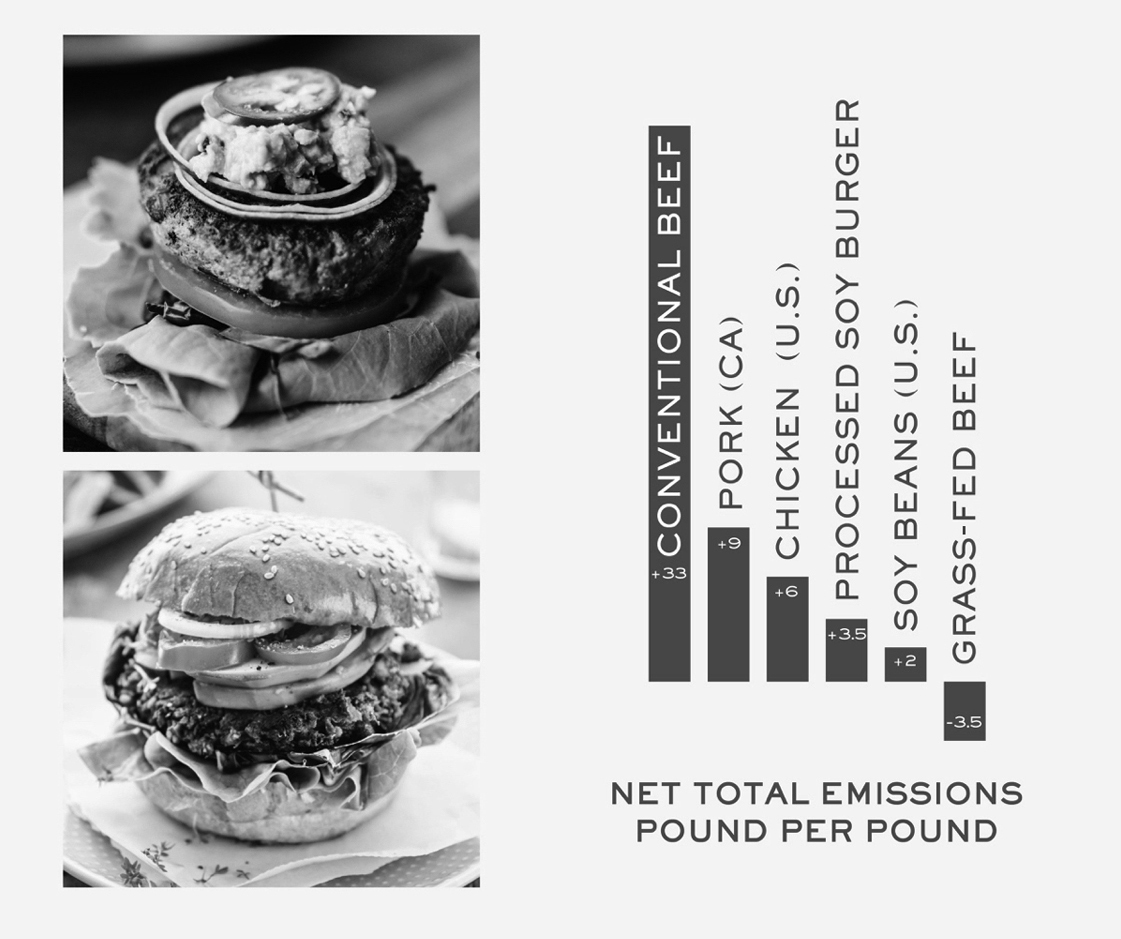

Methane is released from factory-farmed cattle. It is also released by grass-finished cattle, which some suggest may produce more total methane because it takes longer for those cattle to grow to be market ready. However, this fails to account for the quality of feed (grasses), which leads to less methane production, or methane-fixing bacteria in the soil on rich grasslands, or that the net greenhouse gas emissions on regenerative ranches is negative (meaning more GHGs are stored than released into the environment, actually helping reverse climate change).8

Methane is released from factory-farmed cattle. It is also released by grass-finished cattle, which some suggest may produce more total methane because it takes longer for those cattle to grow to be market ready. However, this fails to account for the quality of feed (grasses), which leads to less methane production, or methane-fixing bacteria in the soil on rich grasslands, or that the net greenhouse gas emissions on regenerative ranches is negative (meaning more GHGs are stored than released into the environment, actually helping reverse climate change).8

Nitrogen fertilizer pollution turns into nitrous oxide (far more potent than carbon dioxide).

Nitrogen fertilizer pollution turns into nitrous oxide (far more potent than carbon dioxide).

Food waste in landfills is responsible for off-gassing of GHGs (methane).

Food waste in landfills is responsible for off-gassing of GHGs (methane).

Food transportation, processing, and refrigeration use fossil fuels all along the food chain.

Food transportation, processing, and refrigeration use fossil fuels all along the food chain.

Globally, agriculture and related deforestation are responsible for about a quarter of GHGs, but when every aspect of the food chain is included, it may be more like 50 percent.9 We must transform our agriculture and food systems to avoid dangerous damage to the climate. In fact, our very survival as a species may depend on it. If we are smart enough, if we act now, we can avert it.

SHOULD WE ALL BE VEGAN OR IS GRASS-FED MEAT THE MOST VEGAN THING YOU CAN EAT?

You’ve probably read or heard that meat is bad for the climate (and your health) and that we should adopt plant-based diets in order to lower our carbon footprint and prevent disease. The idea goes that if we all become vegans, or close to it, we can save the world and ourselves.

Meatless Mondays, cow farts, plant-based lab meat, and Impossible-brand plant-based GMO soy burgers are all buzzwords swirling around these days. I’m all for eating lots of vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, real whole grains, and beans. In fact, I have spent most of my career as a doctor telling people to do just that. We clearly should all be eating a plant-rich diet for our health. And there is no argument that feedlots are anything other than an unmitigated disaster for the cattle finished in them, the humans who eat them, and the planet. Case closed, right? Well, Nicolette Hahn Niman, the vegetarian cattle rancher who wrote Defending Beef, put it this way: “It’s not the cow; it’s the how,” a catchphrase she borrowed from Russ Conser, one of the Soil Carbon Cowboys.

First let’s talk about CAFOs and how and why they are so bad for our climate. According to a UN Food and Agriculture Organization figure, using a full life-cycle assessment, livestock are responsible for 14.5 percent of human GHG emissions, more than all transportation emissions.10 Eighty percent of these emissions come from ruminants (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats), half being methane, a quarter nitrous oxide, and the rest carbon dioxide.11 The feed required for these operations is often grown with the worst agricultural practices: annual tilling combined with pesticides and fertilizers, often accompanied by deforestation and use of native grasslands to grow food for the animals. Native grasslands are being lost faster than our forests, with dire consequences for the climate and the environment.12 Preserving grasslands through regenerative livestock integration is essential and profitable.13 In fact, 70 percent of available agricultural lands are used to grow feed for animals in feedlots for human consumption. A report released by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy calculated emissions from the entire supply chain. Their study found that the world’s top five meat and dairy producers combined—Brazil’s JBS, New Zealand’s Fonterra, Dairy Farmers of America, Tyson Foods, and Cargill—emit more GHGs than oil companies ExxonMobil, Shell, or BP. If these meat and dairy companies continue to grow conventional meat and dairy based on current projections, by 2050 they will be responsible for 81 percent of global emissions.14

It should end. Period. Full agreement on all sides.

So, the logical answer, it would seem, is to all become vegan. Not so fast. Not all farms and ranches are the same, nor are all cattle. Grass-fed beef, managed the right way, is good for animals, humans, the environment, and the climate. In fact, properly managed livestock on grasslands and on diversified farms can convert inedible grasses on land unsuitable for crops into healthy protein and nutrients for humans. Well-managed grazing is the most important strategy to create the new soil required to suck carbon out of the atmosphere and save us from extinction.

IT’S NOT THE COW; IT’S THE HOW!

Ranchers who raise grass-fed beef under holistic management (a very specific method of grazing) actually do a lot of good. This term, holistic management, is used interchangeably with “adaptive multi-paddock grazing.” Cattle can stimulate the growth of grasses in a way that sequesters, or absorbs, carbon. When cattle are managed through techniques like mob grazing, which mimics the behavior of natural herd animals, they eat some of the grass and then are moved, giving the grass a chance to regenerate. This regeneration draws down carbon through photosynthesis and pushes it through the grass’s roots to stimulate the soil biology, as we discussed in the previous chapter.

Other research claims that the amount of methane released into the air from ruminants such as cattle surpasses the amount of carbon those animals sequester on rangelands. The Grazed and Confused report, written by Tara Garnett, a vegetarian, from the Food Climate Research Network found that ruminant methane emissions outweigh the carbon sequestration capacity of grasslands.15 This is important because methane is a powerful GHG and over the last decade, methane emissions have been rising. Rice cultivation also contributes to climate change and accounts for 10 percent of GHG emissions globally and up to 19 percent of methane emissions. No one says to cut our rice consumption by 90 percent, although innovative methods of rice cultivation can dramatically reduce those emissions. Methane is also produced from poor manure management on CAFOs, and, yes, cow burps (actually it’s fermentation from bacteria in ruminants’ guts). Turns out that fracking for natural gas along with the production of synthetic nitrogen used to fertilize commodity crops (like corn) release more methane than animal agriculture.16

Many cite Grazed and Confused as proof that even grass-fed cows are harmful to the environment. However, while many of Garnett’s findings are accurate, there are major flaws in the report.17 Sadly, ideology often mixes with science, leaving the average reader or policy maker dazed and confused. The flaws in Garnett’s report were detailed in a report from the Sustainable Food Trust.18

Studies debunking the idea that grass-fed beef can help reverse climate change focus on old-style continuous grazing, which damages the land, not on holistic management, which uses adaptive multi-paddock grazing. Short-term studies Garnett relied on weren’t long enough for the benefits of increasing soil carbon to be measured. It takes time to regenerate land and bring it back to life. Looking at carbon cycles over four years, a recent study of using adaptive multi-paddock grazing (which rotates livestock around multiple paddocks to avoid overgrazing and stimulate plant growth) in the Midwest found that approach put more carbon back into the soil (where we need it) than into the air (where it does harm),19 taking into account methane produced from grass-fed cows. The few papers on which Garnett’s assessment was based didn’t actually review holistic management, making her assessment of the soil and climate impact of grass-fed cows irrelevant.20

Another recent life-cycle analysis of regenerative methods on the White Oak Pastures farm in Georgia also found net carbon sequestration,21 meaning their farming practices are actually reversing climate change. The degree of sequestration depends on the quality of the soil to start with. Poor soils when rehabilitated will sequester more carbon than soils already in good shape, but much of our soils are depleted to varying degrees and the promise of regenerative agriculture at scale is significant.22

Courtesy of White Oak Pastures

So holistically managed animals can actually be part of a regenerative system that draws carbon out of the atmosphere by building healthy soil and offsets methane emissions as well.23 In fact, high-quality forage in these actively managed pastures is easier for cattle to digest and reduces methane production. The net benefit of this type of management is carbon sequestration.

The Marin Carbon Project studies “carbon farming” and through meticulous research on grasslands in California also proved that properly managed grasslands remove carbon from the atmosphere. The animals are not optional but essential to the cycle of carbon sequestration.24 It’s a complicated ecosystem. Not accounting for the full cycle and all the players could easily lead to a misinterpretation of the data. In a robust study comparing feedlot beef to adaptive-multi-paddock-raised grass-fed cattle, including all the outside inputs and methane, the grass-fed operations reduced net carbon by 170 percent and the feedlots increased net carbon emissions.25

If regenerative operations like White Oak Pastures can net sequester carbon, this is better than removing all animals from the land and converting it to the monocrop soy that is used to create the plant-based Impossible Burgers. While some studies seem to show that regenerative agriculture doesn’t produce a net benefit, they are flawed because they examined only conventional (over)grazing and assumed 50 percent of the land was irrigated.28 True holistic management doesn’t require irrigation and builds more soil that holds more carbon. In fact, a comparative analysis of true regenerative practices (from White Oak Pastures) compared to those used to grow GMO monocrop soy for Impossible Burgers found that you would have to eat one 100 percent grass-fed burger to offset the GHG emissions produced by one Impossible Burger.29 The life-cycle analyses for both the grass-fed burger and the Impossible Burger were done by the same research organization, Quantis.

Courtesy of White Oak Pastures

We should be cautious of anyone trying to sell a simplified food solution that requires eliminating cows from the planet or eating only vegan. The suggestion to completely cut out meat also means we’d be cutting out essential amino acids, high-quality protein, and highly bioavailable nutrients such as preformed vitamins A1, K2, D3, and B12 from our diet. If we ditched meat, where would the alternative plant-based protein come from? Nuts and soy still have an environmental and climate impact if grown with conventional methods. We can’t convert rangeland used for livestock into cropland because it is often “marginal,” meaning the soil quality and/or moisture won’t allow crops to grow. Additionally, the tilling and irrigation required to convert rangeland into cropland to grow more soy, corn, and wheat winds up producing more CO2. So, without livestock, we would forgo the use of rangeland that could do two very important things: (1) generate high-quality, nutrient-dense protein, and (2) restore ecosystems and biodiversity and store large amounts of rainwater and carbon, creating a virtuous cycle of fertility, food, and environmental restoration.

The best solution for rangelands is managing livestock in ways that sequester carbon, help prevent floods and droughts, and promote biodiversity. On top of that, water consumption by animals on rangelands is mostly rainwater, so it doesn’t contribute to depletion of the earth’s fresh water the way the irrigation required to grow feed for feedlot cattle does.

Regenerative grazing restores the land and supports livestock and all forms of wildlife—a beautiful ecological cycle. Land regenerates as the soil is restored. With better grazing practices, where cattle eat only half the forage before being moved, the root mass is retained. And the roots continuously pump carbon into the ground. This causes the soil structure to improve and thus more water infiltrates and is retained. The nutrients from the soil are more available. There’s more plant growth and forage, which in turn transpire both water vapor and monoterpenes, molecules created by forests that form aerosols, which create clouds, create more rain, and cool the climate. Soil science, botany, and atmospheric science are all closely interconnected. The circle of life!

It is often pointed out that grass-fed meats are expensive and elitist and can’t be scaled. But they can, and then some. Allen Williams, PhD, has done the math.30 There are 29 million grain-fed cattle consumed from factory farms in America every year. By using idle grasslands, including existing USDA Conservation Reserve Program land unsuitable for farming but good for grazing, and converting corn and soy monocrops used for fattening feedlot cows, we could produce 52.9 million grass-fed head of cattle a year, which is almost double what’s produced in feedlots today. Those grass-fed cattle would help revitalize rural communities, reverse climate change, increase biodiversity, reduce water use, and improve soil health. Similar approaches can be used globally. While we don’t need that much meat, the argument that this is simply an elitist, limited strategy is clearly false.

Agriculture is massively destructive—and not just factory farms. Even growing beans, grains, and vegetables is inherently harmful because the natural ecosystem and animal habitat supporting wild animals such as rabbits, rodents, turkeys, bees, earthworms, and insects is destroyed, not to mention the living, breathing system that is soil and all its trillions of inhabitants. A 2018 study entitled Field Deaths in Plant Agriculture estimated that 7.3 billion animals are killed every year from plant agriculture. Even organic vegetable farms use bone meal and oyster shells to enhance soil and plant health.31 I respect the moral choice of being a vegan, but the idea that it is saving animals and the planet and even improving our health is unfortunately not true. Turns out a cornfield is much more destructive than a grass-fed beef regenerative farm or ranch.

THE EAT-LANCET COMMISSION REPORT ON HEALTHY DIETS AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS

The good news is that there is increasing awareness and extensive science on the links between our current food system, how and what food it produces, and the links to health, the environment, and climate. The EAT-Lancet Commission report was a notable attempt to highlight these issues.

The report got a lot right:

The need for plant-rich diets

The need for plant-rich diets

Reductions in sugar and processed foods

Reductions in sugar and processed foods

Reduction or elimination of factory-farmed meat

Reduction or elimination of factory-farmed meat

Highlighting the importance of transitioning to sustainable agricultural systems that address environmental degradation and climate change and the need to feed a population of 10.5 billion by 2050 in a sustainable way for the planet

Highlighting the importance of transitioning to sustainable agricultural systems that address environmental degradation and climate change and the need to feed a population of 10.5 billion by 2050 in a sustainable way for the planet

Providing flexible guidelines for diet that match cultural and geographical needs

Providing flexible guidelines for diet that match cultural and geographical needs

Providing the first-ever scientific modeling connecting diet, environment, and climate to create healthy humans, environment, and climate

Providing the first-ever scientific modeling connecting diet, environment, and climate to create healthy humans, environment, and climate

While there are always challenges in modeling and the underlying science that informs any attempt at developing guidelines, the report takes a big leap forward in defining the issues and spurring further research and policy actions. However, many scientists have taken issue with the science, the omissions, and the conclusion that we should dramatically reduce meat consumption (the average American man consumes 68 grams of meat a day, or about 10 ounces, while the EAT-Lancet advises only 7 grams a day, or one ounce—one once of protein is about 7 grams), which can produce a nutritionally deficient diet.32 The EAT-Lancet Commission does acknowledge that the sick, elderly, malnourished, and young have higher protein needs that cannot be met by a plant-based diet and that low consumption of animal-based foods in children results in stunting, anemia, and malnutrition, while increased consumption of those foods results in improved growth, nutritional status, cognitive performance, motor development, and health.

The data on the harmful effects of meat used in their analysis is from population-based studies fraught with problems, the biggest of which is that cause and effect cannot be determined from those studies. It is an association that can and does have many other explanations. In rigorous reviews, up to 80 percent of these conclusions from population-based studies turn out to be false when subjected to proper clinical trials. These are the other issues that have been identified with the EAT-Lancet Commission report:

No explicit recognition that well-managed holistic farm and rangeland ecosystems require animals to sequester carbon

No explicit recognition that well-managed holistic farm and rangeland ecosystems require animals to sequester carbon

Calls for increased use of chemical inputs, which is perplexing considering the toxicity of nitrogen pollution to the soil, water, and climate, to support growth in developing countries, which may be better served by more local, regenerative practices that don’t depend on outside chemical and seed inputs

Calls for increased use of chemical inputs, which is perplexing considering the toxicity of nitrogen pollution to the soil, water, and climate, to support growth in developing countries, which may be better served by more local, regenerative practices that don’t depend on outside chemical and seed inputs

Contradictory mention of managed grazing and the use of manure as part of the solution but no acknowledgment of the profound difference between CAFO meat and grass-fed regeneratively raised meat

Contradictory mention of managed grazing and the use of manure as part of the solution but no acknowledgment of the profound difference between CAFO meat and grass-fed regeneratively raised meat

Thirty-one out of thirty seven scientists behind the report have published records in favor of vegan or vegetarian diets or against meat

Thirty-one out of thirty seven scientists behind the report have published records in favor of vegan or vegetarian diets or against meat

No external peer review, and conflicts of interest not reported

No external peer review, and conflicts of interest not reported

Members of their corporate partner FReSH (Food Reform for Sustainability and Health)33 hail from big seed monopolies, fertilizer giants, agrochemical companies, Big Pharma (seven companies), and food behemoths including Bayer (Monsanto), DuPont, Syngenta, Yara (the biggest nitrogen fertilizer company), PepsiCo, and Cargill34

Members of their corporate partner FReSH (Food Reform for Sustainability and Health)33 hail from big seed monopolies, fertilizer giants, agrochemical companies, Big Pharma (seven companies), and food behemoths including Bayer (Monsanto), DuPont, Syngenta, Yara (the biggest nitrogen fertilizer company), PepsiCo, and Cargill34

Twenty of the largest Big Food companies signed up to support the report. Why would they be supporting this platform? Hidden within it is the implicit need to grow more grains and beans and food products using industrial agriculture, seeds, fertilizer, and chemicals that drive profits for all these companies.

Physicist and agroecologist Dr. Vandana Shiva says that the EAT-Lancet report evades the “glaring chronic disease epidemic related to pesticides and toxins in food, imposed by chemically intensive industrial agriculture and food systems.”35 She says, “Instead of recognizing the role of organic farming and agroecology for providing sustainable ways for repairing the broken nitrogen cycle, the report recommends ‘redistribution of global use of nitrogen and phosphorus,’ which in effect is saying chemicals should be spread in the Third World.”36 We’ve already exported our ultraprocessed foods to developing countries to the detriment of their health. Should we really harm them even more by exporting our chemicals, and expanding extractive, fossil-fuel, and chemical-industrial agriculture to grow more grains and beans?

It is true that the developed world eats too much meat, and the wrong meat. But eating less meat and better meat is good for you and the planet. Meat can be responsibly raised and ideally should complement a plant-rich diet.

BUT ISN’T MEAT BAD FOR OUR HEALTH?

The question of whether meat is bad for our health has been extensively debated, sadly mostly along ideological lines, not accurate scientific data. Nearly all studies on the harm of meat studied only factory-farmed meat, and they are population-based studies that cannot prove cause and effect. Meat eaters in those studies were an unhealthy lot. They smoked more, drank more, ate less fruits and vegetables, exercised less, and ate 800 more calories a day than the non–meat eaters.37 Many other studies contradict those findings as well. The PURE study of 135,000 people found those who ate animal protein and fat had fewer heart attacks and deaths than those who ate more cereal grains.38 Another study of food consumption patterns in forty-two countries showed a lower risk of heart disease and death in those who ate animal fat and protein and higher risk in those who ate cereal grains and potatoes.39 A 17-year study of vegetarians and meat eaters who shopped at health food stores found mortality dropped in half for both groups.40 Other studies point to the nutritional benefits of grass-fed meat, including higher levels of omega-3 fats and CLA (a metabolism-boosting anti-cancer fat) and high levels of minerals, vitamins, and antioxidants.41

I have reviewed this subject extensively in my book Food: What the Heck Should I Eat? I also recommend, for those who want to take a deep dive into the research, Chris Kresser’s online review of the science, called “Why Eating Meat Is Good for You.”42 Read the data. Decide for yourself. Avoid relying on inflammatory documentaries or others’ interpretation of the science (including mine).

FOOD FIX: ADAPTING FOOD SYSTEMS TO CLIMATE CHANGE

The worse climate change becomes, the harder it will be to grow crops in hotter, more unstable climate conditions. The faster we can transform the food system, the better we will be in terms of buffering the effects of climate chaos.

It may seem complex to transform agriculture. And it is. We need overall change of the economic, political, and agricultural systems that cause environmental destruction. We need to build systems that can address regeneration of soil, water, climate, biodiversity, and human communities. Luckily, efforts are already underway.

You may have heard about Project Drawdown, a quantified study of the eighty most effective solutions to climate change. Paul Hawken started Project Drawdown to change the climate narrative from doom and gloom and to focus on solutions that currently exist. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming (because no other plan has been proposed) lays out all the solutions that are scientifically established. This is not just about slowing emissions, converting to renewable energy, climate mitigation, or carbon taxes or credits, which are most of the solutions proposed in the Paris Accord. Those measures are necessary but not sufficient. What’s required is literally to massively reduce or draw down carbon from the atmosphere.

Project Drawdown collected proven, data-driven, economically viable, commonly available solutions that remove carbon from the atmosphere while saving billions of dollars, far offsetting the costs of implementing the solutions. Nothing new needs to be invented, though innovation will drive more solutions over time. Hawken brought together a team of seventy scientists from twenty-two countries that analyzed the data and mathematically modeled the most effective ways to reduce GHG emissions as well as take carbon out of the atmosphere and put it back into the soil. Each solution is measured by gigatons of CO2 reduced, the cost to implement, and the billions saved. Guess what tops the list. Food-related solutions collectively were the number one solution to reverse global warming. We also need to draw down fossil-fuel extraction worldwide while scaling up renewable energy.

The data is clear: Our food system as a whole is the number one cause and the number one solution to climate change. Project Drawdown outlines the food-based strategies that collectively will make the biggest difference for human and planetary health.43

Support regenerative agriculture, optimizing farmland irrigation and managed grazing, which is estimated to reduce CO2 by 23 gigatons and save $1.93 trillion on an investment of $57 billion.

Support regenerative agriculture, optimizing farmland irrigation and managed grazing, which is estimated to reduce CO2 by 23 gigatons and save $1.93 trillion on an investment of $57 billion.

Shift agriculture to support a plant-rich diet that is ideally regeneratively grown (which doesn’t mean going vegan, just eating mostly plants).

Shift agriculture to support a plant-rich diet that is ideally regeneratively grown (which doesn’t mean going vegan, just eating mostly plants).

Restore depleted farmland and protect the Amazon rain forest from expanding cattle ranching and monocrop soy production for CAFOs. Deforestation is also driven by land speculation because land without trees is worth 100 to 200 times more than land with forest.

Restore depleted farmland and protect the Amazon rain forest from expanding cattle ranching and monocrop soy production for CAFOs. Deforestation is also driven by land speculation because land without trees is worth 100 to 200 times more than land with forest.

Address food waste, including mandated food composting. Composting addresses food waste while improving soil health.

Address food waste, including mandated food composting. Composting addresses food waste while improving soil health.

Reduce fertilizer use and improve nutrient management to draw down 1.8 gigatons of CO2 and save farmers $102 billion.

Reduce fertilizer use and improve nutrient management to draw down 1.8 gigatons of CO2 and save farmers $102 billion.

Improve rice cultivation (which now accounts for 10 percent of GHG emissions and 19 to 29 percent of global methane emissions).

Improve rice cultivation (which now accounts for 10 percent of GHG emissions and 19 to 29 percent of global methane emissions).

Intercrop trees and crops to reduce inputs and create healthier crops and higher yields.

Intercrop trees and crops to reduce inputs and create healthier crops and higher yields.

Develop silvopasture, lands that integrate trees with pastures for cattle or livestock that forage in the forests.

Develop silvopasture, lands that integrate trees with pastures for cattle or livestock that forage in the forests.

Scale no-till farming and conservation agriculture.

Scale no-till farming and conservation agriculture.

Plant more tropical staple food trees such as avocados, coconuts, and tree legumes to provide food and sequester carbon.

Plant more tropical staple food trees such as avocados, coconuts, and tree legumes to provide food and sequester carbon.

Create government financial incentives for new enzyme and algal technologies that greatly reduce methane emissions from cows.

Create government financial incentives for new enzyme and algal technologies that greatly reduce methane emissions from cows.

All these practices have been scientifically quantified in both cost savings and gigatons of carbon that would be reduced.

ENDING FOOD WASTE: A SOLUTION FOR HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Imagine throwing away a third of your paycheck. Ridiculous, right? Well, a third to half of the food we grow does not make it from the farm to your fork to your belly. To grow the food we waste in the United States, it would take 780 million pounds of pesticides and 4.2 trillion gallons of water on 30 million acres of cropland.44 To grow all the food we waste around the world—about 1.6 billion pounds’ worth—it would take the entire landmass of China!45 And the loss of all that food costs our economy $2.6 trillion a year, or about 4 percent of global world product.46

This is an obvious waste of resources at every stage. Think of the labor, seeds, water, energy, land, fertilizer, and money that end up in the landfill. Even worse, when this wasted food sits in the landfill, it undergoes anaerobic decomposition (decomposition without oxygen) and generates methane gas—a powerful GHG. If you are worried about cow burps, you should be much more worried about the consequences of your veggies ending up in a landfill. Under the current system, the food we waste is responsible for roughly 8 percent of global emissions. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of GHGs after the United States and China.

The new UN Sustainable Development Goals have called for cutting food waste in half by 2030.47 Food waste can happen because prices are too low, and farmers leave food to rot in the fields because it is not worth selling even though it is perfectly good. Food waste can also come from food that is ugly, misshapen, or not “perfect,” like the 800 million pounds of sun-bleached watermelons that are thrown out every year.48 Food service companies, restaurants, retailers, and consumers waste food at each step, and much ends up in landfills. Grocery chains police their garbage to make sure dumpster divers don’t get their slightly overripe food—which, by the way, is still safe to eat. Restaurants overorder to be sure not to run out of anything and disappoint their customers.

Rich and poor countries waste food for different reasons and need different solutions. While poor countries struggle with lack of refrigeration, bad roads, heat, humidity, and lack of proper packaging, they waste almost no food once it enters the home. But rich countries throw out massive quantities of food. Americans throw out 35 percent of the food in their fridge.49 “Best by” and “sell by” dates are related not to food safety but to when the food will taste best, which only confuses customers and leads to massive food waste.

A family of four throws away $1,800 in food every year,50 and in the United States we spend $218 billion a year, or 1.3 percent of our GDP, growing, processing, transporting, and disposing of food that is never eaten.51 We have more than enough food to feed all 7 billion humans. We grow enough food for 10.5 billion. But more than 40 percent (some estimate more) is wasted at every step in the food chain.52

FOOD FIX: FOOD WASTE INNOVATIONS

No one is for food waste. The US government has made addressing it a priority. In October 2018, the USDA partnered with other agencies on the Winning on Reducing Food Waste Initiative. This is big! The government is focused on research, community investments, education and outreach, voluntary programs, public-private partnerships, tool development, technical assistance, event participation, and policy discussion to end food waste. Reducing our GHG emissions and our food waste will require all hands on deck working with local governments, national policy makers, farmers, distribution chains, grocery chains, restaurants, food service providers, and every citizen in their kitchen. Wherever I have lived for the past 40 years, I have had a compost pile. Even in New York City I can drop off food scraps at a farmers’ market in Union Square to be composted. Some cities and countries mandate a zero-waste policy for food scraps. A few key innovators are worth mentioning.

France. The French have a law that grocery stores cannot throw out any food. It must be composted or given to food banks or charities. Grocery store owners must pay a $4,500 fine or go to jail for two years if they throw food in the garbage.54

France. The French have a law that grocery stores cannot throw out any food. It must be composted or given to food banks or charities. Grocery store owners must pay a $4,500 fine or go to jail for two years if they throw food in the garbage.54

San Francisco. San Francisco turns garbage into profit with their new composting law, the Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance, which makes composting mandatory, even for tourists. The city provides the bins for every citizen. This is a win-win solution. Not only do they avoid food in landfills, which causes climate change, but they also contribute to the solution of building healthy soils.

San Francisco. San Francisco turns garbage into profit with their new composting law, the Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance, which makes composting mandatory, even for tourists. The city provides the bins for every citizen. This is a win-win solution. Not only do they avoid food in landfills, which causes climate change, but they also contribute to the solution of building healthy soils.

Apeel Sciences. This company has created an edible, safe, vegetable-derived coating for produce that more than doubles shelf life, protecting it from the farm to your fridge.

Apeel Sciences. This company has created an edible, safe, vegetable-derived coating for produce that more than doubles shelf life, protecting it from the farm to your fridge.

Imperfect Produce. Twenty billion pounds of perfectly good produce are thrown out on farms because they are not perfect or they are funny-looking. Who wants a carrot with two legs, or a weird-looking potato? I do. Imperfect Produce solves this problem by taking millions of pounds of ugly food thrown out at farms, packaging them up, and shipping them directly to your door. Buy ugly food. Save the planet; feed yourself.

Imperfect Produce. Twenty billion pounds of perfectly good produce are thrown out on farms because they are not perfect or they are funny-looking. Who wants a carrot with two legs, or a weird-looking potato? I do. Imperfect Produce solves this problem by taking millions of pounds of ugly food thrown out at farms, packaging them up, and shipping them directly to your door. Buy ugly food. Save the planet; feed yourself.

Food activists have pointed out that Imperfect Produce’s strategies take food waste from industrial agriculture and resell it at a discount, undermining the economic base of local farmers and community-supported agriculture.55 Imperfect Produce is doing good and giving conscious consumers a chance to do the right thing, but we need educated and critical conversations about the effect innovations will have across the spectrum of agriculture and consumers.

WTRMLN WTR. The founder of this company turns 800 million pounds of ugly watermelon that are thrown out every year into the most delicious, nutrient-dense, low-sugar beverage, which beats out coconut water in minerals, nutrients, and electrolytes. It’s the Gatorade replacement.

WTRMLN WTR. The founder of this company turns 800 million pounds of ugly watermelon that are thrown out every year into the most delicious, nutrient-dense, low-sugar beverage, which beats out coconut water in minerals, nutrients, and electrolytes. It’s the Gatorade replacement.

Food Maven. This company takes oversupply from grocery stores and imperfect or ugly food and produce from local farmers and ranchers who have a hard time getting their food to market and provides a marketplace for restaurants to buy the food at 50 percent off.

Food Maven. This company takes oversupply from grocery stores and imperfect or ugly food and produce from local farmers and ranchers who have a hard time getting their food to market and provides a marketplace for restaurants to buy the food at 50 percent off.

FOOD FIX: WHAT YOU CAN DO

Here’s how you can join the movement to save our planet and transform the food system.

1. Eat at restaurants that serve organic, farm-to-table, and/or regenerative food. Restaurants all over the world are putting sustainability on the menu, supporting local food systems, preserving lost varieties of vegetables and animals, and more. Restaurants across the world are embracing sustainability and healthier eating. Find ones in your neighborhood.

2. Look for food labels that identify sustainable, humane food sources including American Grassfed Association, American Humane Certified, Animal Welfare Review Certified, Global Animal Partnership, Certified Sustainable Seafood MSC, Biodynamic, and Bird Friendly, among others.

3. Support innovation and policies for food and agricultural practices that help to reverse climate change. Elect leaders who are committed to implementing policies that support regenerative agriculture and reduce the use of fossil fuels and bring us closer to 100 percent renewable power.

4. Start and support businesses that draw down carbon through agroforestry, silvopasture, holistic grazing, and composting operations. Learn more from groups like Land Link, LandCoreUSA, and Regeneration International.

5. Reduce your own food waste. Use Fresh Paper, a simple piece of paper infused with herbs that keeps your produce fresh three to four times longer, or use produce protected by Apeel, the plant-derived coating that keeps produce fresher longer. Make soups or stews from veggies that are a little wilted. Cook just enough for your family, and make sure to eat all your leftovers.

6. Start a compost pile. That way, whatever waste or food scraps you produce don’t end up in a landfill. No more produce, grains, or beans in landfills. Composting allows food scraps to biodegrade aerobically by exposing them to oxygen, rotating the food scraps, and mixing them with brown matter (such as sawdust, cardboard, or leaves). This turns it into a nutrient-rich organic material that can be used to help build soil in gardens, farms, or your backyard.

Studies found that when compost is applied to rangelands, the compost increased production between 40 and 70 percent, increased soil carbon sequestration, which pulls carbon dioxide from the air into the ground, allowed soil to hold more water, and provided nitrogen and other nutrients to improve soil quality.56 Your garbage can help reverse global warming.

If you live in a city, consider advocating for a municipal-level composting program. Find out if there is an urban compost drop-off center in your city or town. If you have a backyard, create a compost pile there. If you live in an apartment, get a kitchen composter. You might even consider starting a community or city compost program like the one in Sacramento called BioCycle. Or petition your local government to start one.

Most important, don’t forget to eat well, thank your farmers and ranchers, and remember that fixing our food system is a choice you can make every day. You have patiently waded through a deep, long lesson on the environmental and climate impacts of our food and agriculture system, and what policies, business innovations, and you can do about it. Understanding is the first step in shifting our food system to one that is good for humans, animals, the economy, communities, and the planet. Action at every level is needed to transform our food system. It’s time.