10

Problems with Language and Balance: Jake’s Thing, Stanley and the Women, and Russian Hide-and-Seek

JAKE’S THING (1978)

This novel is a sequel of sorts to Lucky Jim. It imagines what might have happened to Jim Dixon if he had stayed in academia.1 Jake Richardson has, unfortunately, turned into a wanker and he is submitted to a linguistic and communicative trial that recalls Roger Micheldene’s in One Fat Englishman. Critics have failed to recognize that the central artistic dilemma actually recreates the plot of Lucky Jim. Jake Richardson too is stuck with an unattractive romantic partner for whom he feels responsible, and the novel ends with their separation. Like Dixon, he must deliver an address at a university assembly on an unnatural and disagreeable theme. He dreads the address and, instead of offering the arguments for allowing women into the Oxford college Comyns, he gives the opposite view. This is his true opinion for, if a weekend of madrigals with the Welches convinced Dixon of Merrie England’s unmerriness,2 Richardson’s sexual troubles lead him to believe that women are to be avoided at all costs. After enumerating the reasons for barring women from Comyns, he changes sides to argue that some trends cannot be resisted and “it may be better, more advantageous, to yield at once rather than fight on” (195). The hook in the ending takes the audience by surprise and it reinforces Amis’s anti-Empsonian approach of conveying ambiguities through provocative content. It also shows his desire to challenge readerly expectations by again offering a convenient, albeit unsatisfying, conclusion.

The protagonist could have been talking about the novel itself and not a psychiatric workshop when he declares, “this whole thing is all about language” (139). Like Roger Micheldene, Jake Richardson takes matters of language and nationality with the utmost seriousness. Early in the novel “someone from Asia” takes his preferred seat on the bus (36) and he engages in a discussion of the pronunciation of the word “libido” with his psychiatrist “on the basis that we’re talking English, not Italian or Spanish” (36).3 Though he is generally nicer and more tolerant than Micheldene, he too is convinced of his linguistic superiority. Richardson often remarks that the English have become insensitive to language and overlook fundamental truths in favour of perversely complex theories. To prove his thesis, he calls attention to everything from the false advertising in an off-license to his psychiatrist’s linguistic errors. Amis too would make similar points in his usage guide, The King’s English. At the workshop the case against Richardson is succinctly expressed by the young ruffian Chris: “Who gave you the bloody right to be so fucking superior?” (151). As a result of Amis’s growing concern with accepting personal responsibility, the Amisian character does not uncover shams but is himself (quite literally) uncovered. The workshop facilitator, acting as “sham-detector” (157), forces Richardson to strip naked, submit to physical prodding, and endure false praise from the other workshop participants.4 The hero briefly endures then quits, like Micheldene, dropping out of therapy.

The trouble with Richardson’s libido proves to be related to his inability to communicate properly. He used to be attracted to the illusion of female innocence (79) and, after sleeping with a character named Eve, whose promiscuity and garrulousness make her the embodiment of all that is at once attractive and repellent about women from Richardson’s perspective, he will admit: “I despise [women] intellectually” (213). Outside his college, he is accosted by women who are picketing Comyns’ all-male policy. They present him with a dildo on which is written, “Try This One, Wanker!” (101). The scene is ironic, for Richardson is unable to maintain an erection, but word choice suggests that the root of his problem is snobbery. To exonerate himself, he must prove that he is not a “shirker” of responsibilities, the definition offered in the novel for a wanker (115). He fails most gloriously by deceiving Eve, a former lover who is now married. She agrees to have dinner with him on the condition that he will not to try to sleep with her, though he does just that and succeeds.

The artistic subtext of the novel is not merely a regurgitation of the Englishness argument in One Fat Englishman but amounts to a revision of Amis’s language policy. In his mature novels, the issue of personal responsibility becomes a serious concern, as evidenced by Douglas Yandell being held accountable for the passive observation of blunders made by a friend and a lover. Richardson too is measured against a high linguistic and communicative standard and found lacking. Because he avoids communicating with his wife Brenda, she leaves (257), and though he will not talk with his own spouse, he listens to and comforts a mad woman on a bus, mistaking her for a victim of wrongheaded modern psychiatry. At last he realizes his error and sees that she has understood nothing he has said after, “Yes, I do,” his reply to her query: “Don’t anybody think I’ve been given a raw deal?” (67). It is only fitting that Richardson be forced to pay penance for being a wanker by spending time with the most disagreeable person in the book, Alcestis Mabbott. Amis again employs aporia – the textual knot that resists untying – to tease the reader while showing that the punishment fits the crime. Alcestis is the irritating Geoffrey’s wife, and Richardson is dismayed to find that she plans to visit him regularly now that they have both been deserted by their spouses. At the Richardson kitchen table she tells her side of the story of their failed marriages, though the speech is completely drowned out by a passing airplane. Once the engine noise subsides, she says: “Which as far as I’m concerned is an end of the matter” (264). The airplane blocks out Alcestis just as Richardson himself has been blocking out women for years and the reader is made aware of how one-sided his communications with women have been to this point. The novel would perhaps have ended on a more positive note if the hero repented and determined to make an effort – even a half-hearted one in the mode of John Lewis or Ronnie Appleyard – to be better. That he does not is confirmed by a final meeting with his physician, who suggests that his sexual trouble might be physical and treatable with medication. Richardson ponders this and decides that since sexual desire will inevitably bring him into contact with women again he is better off impotent and alone.

For the reader, the novel’s greatest drawback is its pessimism. While Philip Larkin, who shared Amis’s appreciation for nasty humour, praised “the determined foul-mouthedness of the book,” he too found it “rather gloomy on the whole” and said that it made him “depressed” (1992, 590). Most Amis novels include in the background younger, happier people to mitigate the unhappiness of the central characters. This is even the case in Ending Up, as Adela’s grandson arrives with his wife to remind the reader of the continuing existence of life, love, and sanity in the outside world. Jake’s Thing, Stanley and the Women, and Russian Hide-and-Seek never suggest happiness as an option for the young or the old. The chances of Jake Richardson and his wife rekindling their romance are slim and, while it would be hard to fault her for leaving him because of his communicative deficiencies, things can only get worse with her new partner, Geoffrey Mabbott, whose knack for misunderstanding and uttering non sequiturs makes conversation an impossibility (217). This is the conclusion that one arrives at if Richardson’s narration is reliable. But since the story is funnelled through his negative, disillusioned consciousness, it is reasonable to assume that many of the characters are not as bad as they seem. If this exaggeration is deliberate then it is a significant artistic achievement5 on Amis’s part and it helps to explain Richardson’s misogyny, for his failure to see the good in others is one of the causes of his marital problems. However, such an interpretation is weakened by Amis’s use of distorted autobiography in basing Richardson’s treatment on his own psychiatric experiences. If one is to accept Terry Teachout’s characterization of Amis as a “conservative novelist [who] draws full-length portraits of men as they are, not as he would wish them to be” (in Bell 1998, 53),6 then one wonders why he depicted the psychiatric profession to be worse than it was when he encountered it.7 When viewed as cultural commentary, the critical inability to appreciate the subtleties in the argument in Jake’s Thing is doubtless related to the tendency to see Jake Richardson as the successor to Jim Dixon, rather than Roger Micheldene. By shifting the focus to Englishness and comparing Richardson’s trials to those of Micheldene, the novel becomes comprehensible in its insistence on linguistic and communicative responsibility. As part of Amis’s developing artistic vision, characters who refuse to accept their responsibilities – both personal and social – cannot achieve happiness, as Stanley and the Women also argues.

RUSSIAN HIDE-AND-SEEK (1980)

In Russian Hide-and-Seek, Amis’s second “counterfeit world” novel after The Alteration, he presents three situations from previous novels, updates his ideas on Englishness, and offers his first extensive analysis of the potentially harmful effect of the audience on artistic creation. Amis re-writes history so that the Russians have invaded and taken political control of England. In examining life from the perspective of expatriates resistant to foreign culture, he inverts the central situation of his anti-travelogue, I Like It Here. The Russians fit the stereotype of the ugly, unilingual Englishman abroad: they do not travel well. Fifty years of Russian occupation has all but destroyed English cultural history and the effect on the current generation is reflected in the inscription “Hora e sempre” under the rooftop of the Controller’s residence. The narrator explains the inscription’s dual meanings as “now and always” and “now is always” (41). Neither rendition recognizes the past and one is reminded of the Pope’s motto in The Alteration, “No time like the present.” As he did in his first counterfeit world book, Amis protests against the mortal condition, though with increasing despair, for the problem of evil has been reduced to a problem of luck. In this sense, and in the employment of military life as a backdrop, the novel resembles The Anti-Death League. The protagonist, Alexander Petrovsky, is a Russian version of Patrick Standish and the discussion of Englishness that Amis left off in Jake’s Thing is also continued.

For most Amis fans, the novel is oddly unsatisfying because it lacks the verbal ingenuity of his best work. The decision to represent Russian in English translation limits his ability to amuse the reader through language, with only periodic reminders of his true talents in the English gambits used mistakenly by the Russian occupiers. Even at his bleakest, Amis always remembered to squeeze humour from the incorrect but creative English speech patterns of foreigners. From a creative standpoint, the novel deals with the necessity of entertaining one’s audience and one might argue that Amis fails his readership for the same reason that the production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet fails: the audience’s expectations are left unfulfilled. Because the novel is almost humourless, one begins to appreciate the positive contribution made by verbal and linguistic pyrotechnics in most Amis novels. The translation of Russian into bloodless English deprives Amis of the means of amusing the reader in passing – as Shorty did in Ending Up – via accents, mimicry, and word play. Verbal creativity is not only entertaining, but serves to lighten the mood and in Russian Hide-and-Seek the mood is sombre throughout. This is not to say that Amis ought to have returned to the romantic comedy formula. That he did not wish to become formulaic is borne out by his collaborations and genre experiments. However, verbal comedy and linguistic ingenuity were indispensable parts of his narrative voice, and a brief comparison of the malevolent hero of Russian Hide-and-Seek with Patrick Standish reveals that, while they are remarkably similar in their characters and behaviour patterns, Alexander Petrovsky’s lack of humour creates a serious problem of balance. He has no redeeming qualities at all and the reader cannot even temporarily take his side.8

While The Anti-Death League presented a world in which life is essentially ordered and comprehensible, albeit with inexplicable and discomfiting twists of fate, order is disrupted in Russian Hide-and-Seek. This is exemplified by the deadly game of hide-and-seek played by Russian military officers. In The Anti-Death League Amis removed the divine’s hand from Chesterton’s thread and in this novel he eliminates God altogether. To show the randomness of human life, he offers a variation on Russian roulette in which the players call out to each other in the darkness, then remain motionless while the others shoot in the direction of the voices. However, everyone cheats by running before the shooting begins to increase their survival odds. When a newcomer participates, Petrovsky worries that he will naively follow the rules and be shot. After an ominous build-up, the scene ends in tragedy, though the victim is Leo, an experienced player and the game’s instigator. The result is a curious inversion of L.S. Caton’s death, for he was the only person with no connection to the fighting at the end of The Anti-Death League. Leo’s death is more disturbing because it reinforces the thesis that in Russified England life is not only unfair but completely unpredictable. The game that gives the novel its name is, therefore, a cry of despair against the random forces controlling human destiny.

The most important character that recurs from a previous Amis work is Patrick Standish, who is reborn as Alexander Petrovsky. His mother believes that his self-centredness is due to overindulgence in childhood: “All human beings, especially those with good looks or some other advantage over their fellows, need strong opposition when young,” she reasons. “If it isn’t forthcoming, their characters suffer. They become egotistical, impossible to deflect from any course of action they may have set themselves, and yet erratic, given to abrupt, entire changes of direction for no external cause” (130–1). In Take a Girl Like You, Jenny Bunn made a similar speech about a child in her class being, like Standish, “incapable of noticing opposition” (30). Both Petrovsky and Standish engage in malicious pranks and deception that target the innocent, distinguishing them from Dixonesque heroes whose principal goal in tricking others is diversion from boredom. Furthermore, most of Dixon’s pranks are harmless, because his enemies are only fooled temporarily, if at all. But Petrovsky’s malice is apparent from the novel’s opening scene, in which, while horseriding, he frightens a flock of sheep, then returns home and recounts the tale to his sister, weeping in apparent repentance. In another emotional scene he says to his girlfriend, Kitty Wright: “Let me tell you how I feel – how you make me feel.” Once he has done so he concludes: “I wish you could have been ... kidnapped and taken prisoner by Vanag’s men so that I could come riding in to rescue you” (55). He later uses the telephone in typically deceptive Amisian fashion to convince a guard to give him access to munitions. Petrovsky pretends to make a call to a superior officer and the results of his deception are murderous, rather than comical. Because of his cunning and his refusal to recognize opposition, he must be killed to stop him from carrying out the mission. His negative traits – emotionalism, the love of duplicity for its own sake (35), and a twisted sense of honour (79) – are inherited from Patrick Standish, though Petrovsky appears far worse, since he lacks both humour and a sense of the absurd.

The Englishness debate is renewed, not recycled, in the novel, with Amis imagining the effect of cultural deprivation on language. The ironically named Dr Wright notes that “English is a language” but “England is a place” (151), a distinction made to emphasize Jake Richardson’s point that fewer and fewer people living in England can correctly manipulate the language. The English revolt fails primarily for linguistic reasons, as the cultural festival ominously foreshadows. Though it had become customary for Amis to satirize the decorative use of foreign loan words by poseurs, in Russian-Hide-and-Seek English is only ever used only for decorative purposes. Society as a whole is guilty of linguistic posturing. Few of the Russian occupiers speak English fluently, but they employ it for greetings and epithets and, in most cases, its application is incorrect or inappropriate. When the thirty-year-old Theodor Markov addresses the director of security, Korotchenko, who is at least twenty years his senior, as “dear chap,” the latter, unsurprised, calls him “old customer” in reply (16). At a dinner party, Petrovsky is deservedly upbraided for not showing his father proper respect. But when he is told by a young woman at the dinner table to “piss off” (23), the non-reaction of the other guests suggests that either no one understands the phrase or it has taken on a different, inoffensive meaning. Most of the English employed in the novel will seem odd or offensive to native speakers, thereby proving the point that language use (and not one’s nation of birth) is the most accurate measure of Englishness. The people in the novel who are descended from English stock and were born during the occupation have grown up speaking Russian, and they have no more of a claim to be English than the occupiers. It is not surprising then that the “English” revolt should fail.

Through his representation of the decline of culture, Amis shows that art cannot survive and flourish unless there is a reciprocal relationship between artist and audience. He had never thoroughly examined the audience’s side of the relationship, but he does so through a performance of Romeo and Juliet. An analysis of the shortcomings of the audience helps clarify the meaning of reciprocity for Amis, and shows the potential of the audience to exert a negative influence on art. Deprived of their cultural history, the English festival-goers are unable to understand either the intended message or the artistic medium. Their reactions range from boredom, when subjected to a Christian sermon, to anger at an art exhibition and dramatic production. Paintings are vandalized for no apparent reason; John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger inspires laughter; and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet leads to arson and a riot.9 The two plays are of particular importance, for they show that the emphasis on reciprocity affects the relationship between artist and audience. When one considers the performance of Elevations 9 by Roy Vandervane, one sees that Amis was warning of the necessity of educating the audience. In Russian Hide-and-Seek, the audience comes for stimulation and out of curiosity, but the people’s lack of cultural sophistication turns art into unintentional farce. In Girl, 20, critical perversity (the fear of missing out on the next wave of the avant-garde) transforms a musical joke into a sophisticated musical experiment. In both cases, ignorance inhibits understanding.

Perhaps the performance of Look Back in Anger is called “an out-and-out success” (176) because the audience has identified with Jimmy Porter, the lower-middle class hero who is angry at social injustice, but the play is not a comedy and the narrator’s ironic assessment shows that the audience has misinterpreted Osborne’s message: “Only very rarely in the past could the theatre have rung with so much happy, hearty laughter. Afterwards the members of the cast had been chaired round the neighbouring streets by an enthusiastic crowd” (176).10 In contrast, the performance of Romeo and Juliet is poorly received and ends in a violent mob setting fire to the theatre. The illiterate and culturally unprepared audience can neither understand nor appreciate Shakespeare. Amis has the audience eating chocolates throughout because “A Russian researcher of unusually wide reading had come across the remark (sarcastically intended) that chocolates seemed to be compulsory at English theatrical performances” (178), thereby demonstrating the adverse effect of misguided art critics.

In his BLitt thesis, Amis saw it as the artist’s duty to please the audience. Any failure to do so would result in the artist losing his or her audience. Russian Hide-and-Seek examines the relationship between artist and audience in a different way, showing that Amis was becoming disillusioned by wilful misinterpretations of his craft. In the descriptions of both the Osborne and the Shakespeare productions, he enumerates the potential faults on the audience’s side that may hinder a creative artist. First, he shows that unfair audience expectations can lead to trouble. Those in attendance at the performance of Romeo and Juliet

had been looking forward to enjoying themselves and had been bewildered and bored. They had been told over and over again that this was a great play by a great Englishman and there was nothing in it. They had put on these ridiculous clothes and come all this way to be made fools of. It was what some of them had been calling it from the beginning – just another Shits’ trick. (181)

Amis himself could appreciate this type of misunderstanding since many critics and readers measured his novels against Lucky Jim and considered changes in content or style indications of artistic failure rather than a widening of his creative vision. In Russian Hide-and-Seek the audience, not the artist, is inauthentic, as the English have been rendered incapable of appreciating art by decades of cultural deprivation. The most interesting part of Amis’s presentation of these two failed dramatic productions is contained in the suggestion that romantic love cannot survive in the absence of culture. The audience does not recognize Romeo and Juliet as a romance because no one is capable of having a traditional love relationship in Russified England. Petrovsky’s sado-masochistic affair with Sonia Korotchenko serves as the centrepiece in a loveless world.11

STANLEY AND THE WOMEN (1984)

With Amis holding his characters responsible in relation to artistic creation, this is a fascinating, if unsatisfying, novel that features a grudgingly responsible narrator. It also gives us a glimpse into Amis’s narrative method, as changes made to the manuscript draft show that he deliberately created a distasteful protagonist so that readers would not think that Stanley Duke has authorial endorsement. Careful analysis suggests that while Amis was deliberately trying to cause offence in the creation of Duke’s portrait, he expected readers to understand that the world he depicts is so dark precisely because the hero’s perspective is skewed. This was lost on most readers, who concluded that the offensive opinions offered by the hero were also the author’s.

One might characterize Stanley and the Women as an alternative world novel masquerading as a work of literary realism, since the protagonist appears uncomfortable in the increasingly surreal England of the 1980s. While many Amis novels end on uncertain notes, this one begins with ambiguity. Amis offers a disembodied third-person analysis of Susan Duke and her dinner party and finally, after three pages, Stanley Duke, a newspaper advertising manager, reluctantly admits to being her husband and the book’s first-person narrator. The unwillingness to accept responsibility is the root of the hero’s later troubles. William Laskowski notes that “Amis’s narrative habit of initially mystifying the reader at the beginning of his works is at its peak” in this novel, and he claims that the absence of a “steady narrative focus” prepares the reader for “a certain indeterminacy” (1998, 118). It is also an effective way of showing that the hero is a shirker. Duke will try throughout the novel to avoid taking responsibility for portions of the story that are his wife’s, his ex-wife’s, or his son’s. In this respect he resembles Douglas Yandell, the narrator in Girl, 20, who claimed to be “a great believer in letting people decide things like [how to dress] for themselves” (HEHL, 3). In both novels, Amis offers an indictment of those who passively observe the lives and mistakes of their significant others, though the author himself might be accused of the same crime. In forming Stanley Duke’s persona, Amis blended the characteristics of his early sardonic heroes with autobiographical detail to create an unattractive but ambivalent character completely unlike Jim Dixon and Kingsley Amis. The fact that Duke is intended to be different from Dixon or John Lewis is ironically emphasized by what they have in common: humble beginnings and the tendency to fuss over moral issues. The following warning, delivered to Duke by his son Steve’s psychiatrist, could have been lifted directly from That Uncertain Feeling: “I must say it would be a pity if you let concern with your own moral position get in the way of more important things” (128). If he were concerned, he would be John Lewis; however, the psychiatrist has simply failed to read the sarcasm in Duke’s claim to be responsible for Steve’s mental condition. He is not at all concerned. Midway through the book, Duke drives his Apfelsine sports car through South London, and says that he is glad to have escaped the area where both he and Amis were born (117). Again, the casual reader that knew about Amis’s lower-middle-class background and literary success might think that he is, like Duke, a snob who has forgotten his humble beginnings. But to prevent the strict association of Duke with the author, key details from the lives of Amis and the members of his immediate circle are inverted. Susan’s mother is called Lady Daly because her husband was a knighted member of parliament, thereby recalling Lady Kilmarnock, who was Amis’s first, not second, wife. Steve, Duke’s son by his first wife, has aspirations to be a writer and just in case the reader connects him to Martin Amis, the author has Steve destroy a copy of Herzog by Martin’s favourite novelist, Saul Bellow (26).12 And, further, Duke has written about cars and drives a sports car himself. He is planning to write to the editor of Classic Car Club on the subject of exhausts: “I might well work it up into an article – after all, Susan was not the only writer in the family” (55). In this way Amis takes his literary rivalry with Elizabeth Jane Howard and makes the wife well-known and himself a mere amateur. Amis, who knew nothing about cars and did not even drive, turns Duke into an auto enthusiast and, by novel’s end, the newspaper’s new automotive critic (231).

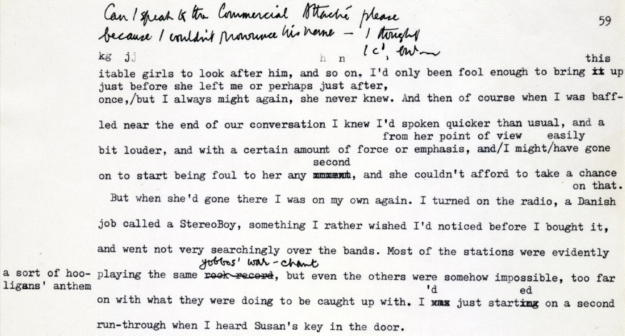

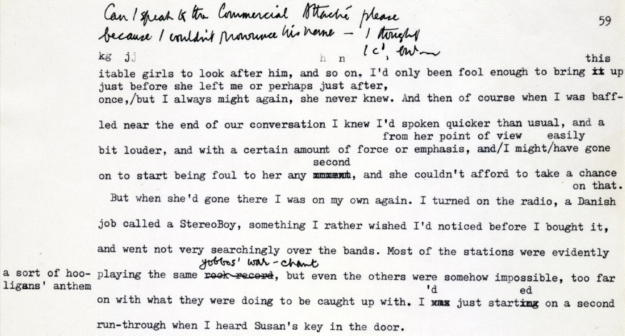

In spite of its faults, Stanley and the Women shows how much Amis’s art had advanced in thirty years. While his failed novel The Legacy was full of pointless details that convey nothing because the narrative perspective is so weak, changes made to Stanley and the Women in manuscript form show that descriptive details reveal as much about the protagonist’s way of viewing as they do about the action. Marginal notes and alterations to the manuscript suggest that Amis decided to make Duke both more complex and more disagreeable. Although the resulting novel is not particularly enjoyable to read, Amis seems to have done it to prevent readers from sympathizing with Duke or thinking that he has authorial endorsement. In the first draft, Duke drives a Porsche and, when trouble arises with the clutch, it is revealed that he knows gearboxes well and has published on the subject. Halfway through the Porsche becomes an Apfelsine, which is apparently intended to be a rarer breed of expensive sports car (128). Amis would, however, forget once, write “Porsche,” cross it out, and make the correction. This change was made to add complexity to Duke’s character. While ownership of a Porsche would be interpreted as status motivated, Duke’s choice of an Apfelsine indicates that he is a true auto enthusiast. This addition of a redeeming characteristic contrasts well with other changes made during the manuscript stage to prevent the reader from sympathizing with Duke. After he calls his mother-in-law by her title, “lady,” without the family name “Daly” he internally remarks that this is “either poetical or vulgar, nothing in between.” Amis then added the following marginal note: “Going too far is a good thing on his part – shd be more setting him up for what is to happen” (HEHL, 16). He would have Duke go too far primarily in his observations of fellow beings. A search for something diverting on the radio at first results in the discovery that “Most of the stations were evidently playing the same rock record.” This became: “Most of the stations were evidently a sort of hooligans’ anthem playing the same yobbos’ war-chant” (HEHL, 59). Another representative alteration occurs when Duke observes an employee at the psychiatric hospital. “I thought that he looked tremendously unmedical” became, “It struck me that this Asian, quite apart from being an Asian, looked tremendously unmedical” (HEHL, 107). Duke is racist, sexist, and intolerant, and his attitude towards his humble beginnings does not endear him to the reader either. “By the time I got to New Cross I had come to within five miles of where I had been born and brought up,” he reports in the manuscript, after which Amis made the following marginal addition: “not changed much, still shitty” (HEHL, 92).

5 Midway through the first paragraph of this manuscript page from Stanley and the Women, the phrase “rock record” is replaced by “yobbos’ war chant.” In several Amis novels in the 1970s, characters with tacit authorial endorsement voice unattractive or offensive opinions. Many of the revisions made to Stanley and the Women in draft prevent the reader from identifying with the central character. While the reader always knows whom to cheer for in his most popular work, Lucky Jim, the author’s sympathies are far from obvious in his commercially and critically less successful later works.

Though the novel was not well-received critically, it signalled another important adjustment in Amis’s developing artistic vision. For perhaps the first time in his fiction, he shows the limitations of art, as the lessons learned through art often have no application to life. Duke’s ex-wife, Nowell, has just appeared in a television drama playing “the maverick matron” in a hospital “who didn’t really think they ought to be torturing the patients to death just yet” (21); she is, however, indifferent to the poor care that her own son receives at the mental hospital, giving all the responsibility to Duke (208). She is a professional actress and medical professionals are described as “colossal actors” (58). Nowell’s role-playing includes a penchant for imaginative interpretation or, as Duke explains, “She makes up the past as she goes along” (98). Her current husband, Bert Hutchinson, is also an actor: he pretends to be perpetually drunk to avoid dealing with his wife (168). Staged episodes in the novel, such as the discovery of a switchblade knife in Steve’s dresser drawer and his beating at the Jabali Embassy, lend it a surrealist air. The most significant such episode is Steve’s attack on his step-mother. This has actually been orchestrated by Susan – she stabs herself in the forearm – as a means of getting him committed to the mental hospital. Nothing is as it seems in Stanley and the Women, and while there are no shamming artists in the novel, there are numerous shamming people, and most of them are women.

The novel is one of Amis’s poorest because he fails to maintain balance, one of the keys to literary success identified in Ending Up. Bernard Bastable’s bile has infected Stanley Duke, who takes a dim view of women, homosexuals, and minorities. Although Amis would defend himself against critics who disliked the novel by insisting that he had portrayed men unfavourably as well, men are not put on trial in the same way that the women are. One witness after another is called by Amis to testify against women as conniving, evil, and mad. The novel would have had a semblance of balance if Amis had limited himself to the polarized views of Stanley and Susan Duke, but he invokes the authority of a medical doctor, a psychiatrist, a newspaper editor, a policeman, a cheerful businesswoman, and a cleaning lady to show that women are manipulative and insane. Although Amis developed the habit of re-examining characters and concepts, he almost always adopted an opposing perspective the second time. However, in his portrayal of both women and psychiatry in Stanley and the Women, he merely repeats the points made in Jake’s Thing. Philip Larkin recognized this as a departure from habit and wrote in a 29 January 1984 letter: “I thought you’d given women a pretty good going-over in JT; still got more to say, eh?” (HEHL). Amis countered that it was “not another JT by any means. None of the sentimental mollycoddling that women get in that. This has moments of definite hostility. It’s an inexhaustible subject” (Amis 2001, 969).13