MODERN PERCEPTIONS OF THE CRUSADES

Fig. 10.1: In this nineteenth-century illustration, a glowing angel appears to guide the crusaders as they march at night toward Jerusalem. From Joseph F. Michaud, History of the Crusades, Illustrated…by Gustave Doré (Philadelphia: George Barrie Publisher, 1877), facing p. 106.

98. David Hume on the Crusades

Philosopher, economist, and historian David Hume (1711–76) typifies the Enlightenment view of the Crusades in his History of England. A leading figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, Hume challenged Christian belief and saw orthodox religion’s role in history as divisive and counter-productive. Hume was influenced by both Voltaire’s and Diderot’s writings on the Crusades. Diderot, in his seminal Encyclopédie, had defined the crusades as “a time of the deepest darkness” and the “greatest folly.” For his part Voltaire argued that “religion, avarice, and a restless anxiety” characterized the crusading movement. Hume’s own History of England (published between 1754 and 1762) was a best-seller in its time, and its views on the Crusades gained a large audience.

Source: David Hume, The History of England, from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Abdication of James the Second, 1688, revised ed. (Boston: Aldine Book Publishing Company, 1776), vol. 1, pp. 226–30.

But the noise of these petty wars and commotions [between the sons of William the Conqueror] was quite sunk in the tumult of the crusades, which now engrossed the attention of Europe, and have ever since engaged the curiosity of mankind, as the most signal and most durable monument of human folly that has yet appeared in any age or nation. After Mahomet had, by means of his pretended revelations, united the dispersed Arabians under one head, they issued forth from their deserts in great multitudes; and being animated with zeal for their new religion, and supported by the vigor of their new government, they made deep impression on the eastern empire, which was far in the decline, with regard both to military discipline and to civil policy. Jerusalem, by its situation, became one of their most early conquests; and the Christians had the mortification to see the holy sepulchre, and the other places, consecrated by the presence of their religious founder, fallen into the possession of infidels. But the Arabians or Saracens were so employed in military enterprises, by which they spread their empire, in a few years, from the banks of the Ganges to the Straits of Gibraltar, that they had no leisure for theological controversy; and though the Alcoran [that is, the Qur’an], the original monument of their faith, seems to contain some violent precepts, they were much less infected with the spirit of bigotry and persecution than the indolent and speculative Greeks, who were continually refining on the several articles of their religious system. They gave little disturbance to those zealous pilgrims who daily flocked to Jerusalem; and they allowed every man, after paying a moderate tribute, to visit the holy sepulchre, to perform his religious duties, and to return in peace. But the Turcomans or Turks, a tribe of Tartars, who had embraced Mahometanism, having wrested Syria from the Saracens, and having, in the year 1065, made themselves masters of Jerusalem, rendered the pilgrimage much more difficult and dangerous to the Christians. The barbarity of their manners, and the confusions attending their unsettled government, exposed the pilgrims to many insults, robberies, and extortions; and these zealots, returning from their meritorious fatigues and sufferings, filled all Christendom with indignation against the infidels, who profaned the holy city by their presence, and derided the sacred mysteries in the very place of their completion. Gregory VII, among the other vast ideas which he entertained, had formed the design of uniting all the western Christians against the Mahometans; but the egregious and violent invasions of that pontiff on the civil power of princes had created him so many enemies, and had rendered his schemes so suspicious, that he was not able to make great progress in this undertaking. The work was reserved for a meaner instrument, whose low condition in life exposed him to no jealousy, and whose folly was well calculated to coincide with the prevailing principles of the times.

Peter, commonly called the Hermit, a native of Amiens in Picardy, had made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Being deeply affected with the dangers to which that act of piety now exposed the pilgrims, as well as with the instances of oppression under which the eastern Christians labored, he entertained the bold, and in all appearance impracticable, project of leading into Asia, from the farthest extremities of the West, armies sufficient to subdue those potent and warlike nations which now held the holy city in subjection. He proposed his views to [the pope], who filled the papal chair, and who, though sensible of the advantages which the head of the Christian religion must reap from a religious war, and though he esteemed the blind zeal of Peter a proper means for effecting the purpose, resolved not to interpose his authority, till he saw a greater probability of success. He summoned a council at Placentia, which consisted of four thousand ecclesiastics, and thirty thousand seculars; and which was so numerous that no hall could contain the multitude, and it was necessary to hold the assembly in a plain. The harangues of the pope, and of Peter himself, representing the dismal situation of their brethren in the East, and the indignity suffered by the Christian name, in allowing the holy city to remain in the hands of infidels, here found the minds of men so well prepared, that the whole multitude, suddenly and violently, declared for the war, and solemnly devoted themselves to perform this service, so meritorious, as they believed it, to God and religion.

But though Italy seemed thus to have zealously embraced the enterprise, [Pope Urban] knew that, in order to ensure success, it was necessary to enlist the greater and more warlike nations in the same engagement; and having previously exhorted Peter to visit the chief cities and sovereigns of Christendom, he summoned another council at Clermont in Auvergne. The fame of this great and pious design being now universally diffused, procured the attendance of the greatest prelates, nobles, and princes; and when the pope and the Hermit renewed their pathetic exhortations, the whole assembly, as if impelled by an immediate inspiration, not moved by their preceding impressions, exclaimed with one voice, IT IS THE WILL OF GOD! IT IS THE WILL OF GOD! Words deemed so memorable, and so much the result of a divine influence, that they were employed as the signal of rendezvous and battle in all the future exploits of those adventurers. Men of all ranks flew to arms with the utmost ardor; and an exterior symbol too, a circumstance of chief moment, was here chosen by the devoted combatants. The sign of the cross, which had been hitherto so much revered among Christians, and which, the more it was an object of reproach among the pagan world, was the more passionately cherished by them, became the badge of union, and was affixed to the right shoulder, by all who enlisted themselves in this sacred warfare.

Europe was at this time sunk into profound ignorance and superstition: the ecclesiastics had acquired the greatest ascendant over the human mind: the people, who, being little restrained by honor, and less by law, abandoned themselves to the worst crimes and disorders, knew of no other expiation than the observances imposed on them by their spiritual pastors; and it was easy to represent the holy war as an equivalent for all penances, and an atonement for every violation of justice and humanity. But, amidst the abject superstition which now prevailed, the military spirit also had universally diffused itself; and though not supported by art or discipline, was become the general passion of the nations governed by the feudal law. All the great lords possessed the right of peace and war: they were engaged in perpetual hostilities with each other: the open country was become a scene of outrage and disorder: the cities, still mean and poor, were neither guarded by walls, nor protected by privileges, and were exposed to every insult: individuals were obliged to depend for safety on their own force, or their private alliances: and valor was the only excellence which was held in esteem, or gave one man the pre-eminence above another. When all the particular superstitions, therefore, were here united in one great object, the ardor for military enterprises took the same direction; and Europe, impelled by its two ruling passions, was loosened, as it were, from its foundations, and seemed to precipitate itself in one united body upon the East.

All orders of men, deeming the crusades the only road to Heaven, enlisted themselves under these sacred banners, and were impatient to open the way with their sword to the holy city. Nobles, artisans, peasants, even priests, enrolled their names; and to decline this meritorious service, was branded with the reproach of impiety, or what perhaps was esteemed still more disgraceful, of cowardice and pusillanimity. The infirm and aged contributed to the expedition by presents and money; and many of them, not satisfied with the merit of this atonement, attended it in person, and were determined, if possible, to breathe their last in sight of that city where their Savior had died for them. Women themselves, concealing their sex under the disguise of armor, attended the camp; and commonly forgot still more the duty of their sex, by prostituting themselves, without reserve, to the army. The greatest criminals were forward in a service which they regarded as a propitiation for all crimes; and the most enormous disorders were, during the course of those expeditions, committed by men inured to wickedness, encouraged by example, and impelled by necessity. The multitude of the adventurers soon became so great, that their more sagacious leaders, Hugh, Count of Vermandois, brother to the French king, Raymond, Count of Toulouse, Godfrey of Bouillon, Prince of Brabant, and Stephen, Count of Blois, became apprehensive lest the greatness itself of the armament should disappoint its purpose; and they permitted an undisciplined multitude, computed at three hundred thousand men, to go before them, under the command of Peter the Hermit, and Walter the Moneyless. These men took the road towards Constantinople through Hungary and Bulgaria; and trusting that Heaven, by supernatural assistance, would supply all their necessities, they made no provision for subsistence on their march. They soon found themselves obliged to obtain by plunder what they had vainly expected from miracles; and the enraged inhabitants of the countries through which they passed, gathering together in arms, attacked the disorderly multitude, and put them to slaughter without resistance. The more disciplined armies followed after; and passing the straits at Constantinople, they were mustered in the plains of Asia, and amounted in the whole to the number of seven hundred thousand combatants.

Amidst this universal frenzy, which spread itself by contagion throughout Europe, especially in France and Germany, men were not entirely forgetful of their present interests; and both those who went on this expedition, and those who stayed behind, entertained schemes of gratifying, by its means, their avarice or their ambition. The nobles who enlisted themselves were moved, from the romantic spirit of the age, to hope for opulent establishments in the East, the chief seat of arts and commerce during those ages; and in pursuit of these chimerical projects, they sold at the lowest price their ancient castles and inheritances, which had now lost all value in their eyes. The greater princes, who remained at home, besides establishing peace in their dominions by giving occupation abroad to the inquietude and martial disposition of their subjects, took the opportunity of annexing to their crown many considerable fiefs, either by purchase, or by the extinction of heirs. The pope frequently turned the zeal of the crusaders from the infidels against his own enemies, whom he represented as equally criminal with the enemies of Christ. The convents and other religious societies bought the possessions of the adventurers, and as the contributions of the faithful were commonly entrusted to their management, they often diverted to this purpose what was intended to be employed against the infidels.

Questions: In what ways is this description of the Crusades a product of the Enlightenment? What characteristics does Hume share with medieval Western writers? What does Hume see as the primal motivating factors for the crusading movement? What are his views regarding Muslims and the Islamic society of the crusading period?

99. Edward Gibbon’s Evaluation of the Crusades

Edward Gibbon (1776–94) is best known for his monumental work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Published between 1776 and 1788, it reflects many of the themes of Enlightenment thinkers, including a belief in humanity’s progression from superstition to mature reason. Gibbon’s negative view of the Middle Ages, in particular the institution of the church, was common among the Enlightenment fraternity. We can also see in the History a strong economic thread, as it was believed that trade and industry played a significant role in the progress and health of the state. These concerns are clearly evident in this passage where Gibbon, after having told the story of the Crusades, sums up the results of the crusading movement.

Source: Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (New York: 4th American ed., 1826), vol. 6, pp. 109–12.

After this narrative of the expeditions of the Latins to Palestine and Constantinople, I cannot dismiss the subject without revolving the consequences on the countries that were the scene, and on the nations that were the actors of these memorable crusades. As soon as the arms of the Franks were withdrawn, the impression, though not the memory, was erased in the Mahometan realms of Egypt and Syria. The faithful disciples of the prophet were never tempted by a profane desire to study the laws or language of the idolaters; nor did the simplicity of their primitive manners receive the slightest alteration from their intercourse in peace and war with the unknown strangers of the West. The Greeks, who thought themselves proud, but who were only vain, showed a disposition somewhat less inflexible. In the efforts for the recovery of their empire, they emulated the valor, discipline, and tactics, of their antagonists. The modern literature of the West they might justly despise; but its free spirit would instruct them in the rights of man; and some institutions of public and private life were adopted from the French. The correspondence of Constantinople and Italy diffused the knowledge of the Latin tongue; and several of the fathers and classics were at length honored with a Greek version. But the national and religious prejudices of the Orientals were inflamed by persecution; and the reign of the Latins confirmed the separation of the two churches.

If we compare, at the Era of the crusades, the Latins of Europe with the Greeks and Arabians, their respective degrees of knowledge, industry, and art, our rude ancestors must be content with the third rank in the scale of nations. Their successive improvement and present superiority may be ascribed to a peculiar energy of character, to an active and imitative spirit, unknown to their more polished rivals, who at that time were in a stationary or retrograde state. With such a disposition, the Latins should have derived the most early and essential benefits from a series of events which opened to their eyes the prospect of the world, and introduced them to a long and frequent intercourse with the more cultivated regions of the East. The first and most obvious progress was in trade and manufactures, in the arts which are strongly prompted by the thirst of wealth, the calls of necessity, and the gratification of the sense or vanity. Among the crowd of unthinking fanatics, a captive or a pilgrim might sometimes observe the superior refinements of Cairo and Constantinople: the importer of wind-mills was the benefactor of nations; and if such blessings are enjoyed without any grateful remembrance, history has condescended to notice the more apparent luxuries of silk and sugar, which were transported into Italy from Greece and Egypt. But the intellectual wants of the Latins were more slowly felt and supplied; the ardor of studious curiosity was awakened in Europe by different causes and more recent events; and, in the age of the crusades, they viewed with careless indifference the literature of the Greeks and Arabians. Some rudiments of mathematical and medicinal knowledge might be imparted in practice and in figures; necessity might produce some interpreters for the grosser business of merchants and soldiers; but the commerce of the Orientals had not diffused the study and knowledge of their languages in the schools of Europe. If a similar principle of religion repulsed the idiom of the Koran, it should have excited their patience and curiosity to understand the original text of the Gospel; and the same grammar would have unfolded the sense of Plato and the beauties of Homer. Yet in a reign of sixty years the Latins of Constantinople disdained the speech and learning of their subjects; and the manuscripts were the only treasures which the natives might enjoy without rapine or envy. Aristotle was indeed the oracle of the Western universities; but it was a barbarous Aristotle; and, instead of ascending to the fountain-head, his Latin votaries humbly accepted a corrupt and remote version from the Jews and Moors of Andalusia. The principle of the crusades was a savage fanaticism; and the most important effects were analogous to the cause. Each pilgrim was ambitious to return with his sacred spoils, the relics of Greece and Palestine; and each relic was preceded and followed by a train of miracles and visions. The belief of the Catholics was corrupted by new legends, their practice by new superstitions; and the establishment of the inquisition, the mendicant orders of monks and friars, the last abuse of indulgences, and the final progress of idolatry, flowed from the baleful fountain of the holy war. The active spirit of the Latins preyed on the vitals of their reason and religion; and if the ninth and tenth centuries were the times of darkness, the thirteenth and fourteenth were the age of absurdity and fable. In the profession of Christianity, in the cultivation of a fertile land, the northern conquerors of the Roman Empire insensibly mingled with the provincials, and rekindled the embers of the arts of antiquity. Their settlements about the age of Charlemagne had acquired some degree of order and stability, when they were overwhelmed by new swarms of invaders, the Normans, Saracens, and Hungarians, who replunged the western countries of Europe into their former state of anarchy and barbarism. About the eleventh century, the second tempest had subsided by the expulsion or conversion of the enemies of Christendom: the tide of civilization, which had so long ebbed, began to flow with a steady and accelerated course; and a fairer prospect was opened to the hopes and efforts of the rising generations.

Great was the increase, and rapid the progress, during the two hundred years of the crusades; and some philosophers have applauded the propitious influence of these holy wars, which appear to me to have checked rather than forwarded the maturity of Europe. The lives and labors of millions, which were buried in the East, would have been more profitably employed in the improvement of their native country: the accumulated stock of industry and wealth would have overflowed in navigation and trade; and the Latins would have been enriched and enlightened by a pure and friendly correspondence with the climates of the East. In one respect I can indeed perceive the accidental operation of the crusades, not so much in producing a benefit as in removing an evil. The larger portion of the inhabitants of Europe was chained to the soil, without freedom, or property, or knowledge; and the two orders of ecclesiastics and nobles, whose numbers were comparatively small, alone deserved the name of citizens and men. This oppressive system was supported by the arts of the clergy and the swords of the barons. The authority of the priests operated in the darker ages as a salutary antidote: they prevented the total extinction of letters, mitigated the fierceness of the times, sheltered the poor and defenceless, and preserved or revived the peace and order of civil society. But the independence, rapine, and discord of the feudal lords were unmixed with any semblance of good; and every hope of industry and improvement was crushed by the iron weight of the martial aristocracy. Among the causes that undermined that Gothic edifice, a conspicuous place must be allowed to the crusades. The estates of the barons were dissipated, and their race was often extinguished, in these costly and perilous expeditions. Their poverty extorted from their pride those charters of freedom which unlocked the fetters of the slave, secured the farm of the peasant and the shop of the artificer, and gradually restored a substance and a soul to the most numerous and useful part of the community. The conflagration which destroyed the tall and barren trees of the forest, gave air and scope to the vegetation of the smaller and nutritive plants of the soil.

Questions: What is Gibbon’s judgment on each of the three cultures of the crusading era—“Latins,” “Greeks,” and “Arabians”? In his opinion, what did each gain from the other two? Would you call Gibbon a racist? Is the idea of racism a useful one for analyzing writings from the past? Explain his criteria in evaluating the crusaders’ best and worst qualities. What is Gibbon’s argument regarding the economic development of Europe in light of the Crusades?

100. William Wordsworth’s Ecclesiastical Sonnets

The reasoned skepticism that characterized the Enlightenment was followed by the Romantic movement of the nineteenth century. Here emotion, idealism, and a positive interpretation of the medieval past served to romanticize and promote both the Crusades and their European participants. For those of this persuasion, the Christian religion and Crusades were no longer to be seen as instigators of superstitious fanaticism. Instead, Crusading took on the mantle of mystic heroism—the height of chivalric expression from a bygone age. Nowhere is this more evident than in the literature and poetry of the period. Sir Walter Scott set four of his novels in the crusading Holy Land (Ivanhoe, The Betrothed, The Talisman, and Count Robert of Paris), while artists and composers such as Gustave Doré and Edvard Grieg took up the Crusades as fitting subjects for their creative endeavors. Below is an extract from William Wordsworth’s Ecclesiastical Sonnets. Published in 1822 when the poet was in his early fifties, their purpose was to illustrate, as Wordsworth put it, the “progress and operation of the church in England, both previous and subsequent to the Reformation.” This included the Crusades.

Source: A. Potts, The Ecclesiastical Sonnets of William Wordsworth: A Critical Edition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1922), pp. 136–37, 143–44.

The Council of Clermont

“And shall,” the Pontiff asks, “profaneness flow

From Nazareth—source of Christian piety,

From Bethlehem, from the Mounts of Agony

And glorified Ascension? Warriors, go.

With prayers and blessings we your path will sow;

Like Moses hold our hands erect, till ye

Have chased far off by righteous victory

These sons of Amalek, or laid them low!”—

“God willeth it,” the whole assembly cry;

Shout which the enraptured multitude astounds!

The Council-roof and Clermont’s towers reply;—

“God willeth it,” from hill to hill rebounds.

And, in awe-stricken Countries far and nigh,

Through “Nature’s hollow arch” that voice resounds.

The Crusades

The turbaned Race are poured in thickening swarms

Along the west; though driven from Aquitaine,

The Crescent glitters on the towers of Spain;

And soft Italia feels renewed alarms;

The scimitar, that yields not to the charms

Of ease, the narrow Bosphorus will disdain;

Nor long (that crossed) would Grecian hills detain

Their tents, and check the current of their arms.

Then blame not those who, by the mightiest lever

Known to the moral world, Imagination,

Upheave, so seems it, from her natural station

All Christendom:—they sweep along (was never

So huge a host!)—to tear from the Unbeliever

The precious Tomb, their haven of salvation.

Crusaders

Furl we the sails, and pass with tardy oars

Through these bright regions, casting many a glance

Upon the dream-like issues—the romance

Of many-colored life that Fortune pours

Round the Crusaders, till on distant shores

Their labors end; or they return to lie,

The vow performed, in cross-legged effigy,

Devoutly stretched upon their chancel floors.

Am I deceived? Or is their requiem chanted

By voices never mute when Heaven unties

Her inmost, softest, tenderest harmonies;

Requiem which Earth takes up with voice undaunted,

When she would tell how Brave, and Good, and Wise,

For their high guerdon not in vain have panted!

As faith thus sanctified the warrior’s crest

While from the Papal Unity there came,

What feebler means had failed to give, one aim

Diffused through all the regions of the West;

So does her Unity its power attest

By works of Art, that shed, on the outward frame

Of worship, glory and grace, which who shall blame

That ever looked to heaven for final rest?

Hail countless Temples! that so well befit

Your ministry; that, as ye rise and take

Form, spirit, and character from holy writ.

Give to devotion, wheresoe’er awake.

Pinions of high and higher sweep, and make

The unconverted soul with awe submit.

Where long and deeply hath been fixed the root

In the blest soil of gospel truth, the Tree,

(Blighted or scathed though many branches be,

Put forth to wither, many a hopeful shoot)

Can never cease to bear celestial fruit.

Witness the Church that oft-times, with effect

Dear to the saints, strives earnestly to eject

Her bane, her vital energies recruit.

Lamenting, do not hopelessly repine

When such good work is doomed to be undone,

The conquests lost that were so hardly won:—

All promises vouchsafed by Heaven will shine

In light confirmed while years their course shall run.

Confirmed alike in progress and decline.

Questions: What is Wordsworth’s overall estimation of the Crusades and crusaders, and how does he think they should be remembered? How does Wordsworth use capitalization to express ideas? What aspects of the Crusades are deliberately obscured or forgotton? How does his version of Urban’s call to arms in Clermont differ from the medieval accounts of this event? What is his view of Muslims and the Islamic faith, and what threat do they pose, in Wordsworth’s view, to Christian Europe?

101. Michaud, History of the Crusades

Joseph François Michaud’s (1767–1839) Histoire des croisades was perhaps the most popular crusading study of the nineteenth century. Published between 1812 and 1822, its final revised edition appeared in 1841 after Michaud’s death. This mammoth multi-volume work promoted European nationalism (especially with regard to his native France) and maintained its influence well into the twentieth century. Written in the style of romantic fiction, the Histoire was translated into many languages, including Arabic. However, as the crusade historian Christopher Tyerman notes, “The portrait of crusading as mortal combat with a degraded, almost demonised Islam, was one that when, literally, translated into Arabic produced ideological and rhetorical consequences still being played out in modern political conflicts.”33 Christopher Tyerman, The Debate on the Crusades (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), p. 109.

In the first short excerpt below, Michaud describes the less-than-perfect state of medieval Europe prior to the Crusades. In the second, he reflects on the First Crusade.

Source: Joseph François Michaud, The History of the Crusades, trans. W. Robson (New York, 1853), pp. 37–38, 257, 264.

No one would then have been understood who would have spoken of the rights of nature or the rights of man; the language of the barons and the lords comprised only such words as treated of war; war was the only science, the only policy of either princes or states. Nevertheless, this barbarism of the nations of the West did not at all resemble that of the Turks, whose religion and manners repelled every species of civilization or cultivations, nor that of the Greeks [of Byzantium], who were nothing but a corrupted and degenerated people. Whilst the one exhibited all the vices of a state almost savage, and the other all the corruption of decay, something heroical and generous was mingled with the barbarous manners of the Franks, which resembled the passions of youth, and gave promise of a better future. The Turks were governed by a gross barbarism, which made them despise all that was noble or great; the Greeks were possessed by a learned and political barbarism, which filled them with disdain for heroism or the military virtues. The Franks were as brave as the Turks, and set higher value on glory than any other people. The principle of honor, which gave birth to chivalry in Europe, directed their bravery, and sometimes assumed the guise of justice and virtue.

The Christian religion, which the Greeks had reduced to little formulae and the vain practices of superstition, was, with them, incapable of inspiring either great designs or noble thoughts. Among the nations of the West, as they were yet unacquainted with the disputed dogmas of Christianity, it had more empire over their minds, it deposed their hearts more to enthusiasm, and formed amongst them, at once, both saints and heroes….

The imagination of the most indifferent must be struck with the instances of heroism which the history of the crusades abounds in. If many of the scenes of this great epoch excite our imagination or our pity, how many of the events fill us with admiration and surprise! How many names, rendered illustrious by this war, are still the pride of families and nations! That which is perhaps most positive in the results of the first crusade, is the glory of our fathers,—that glory which is also a real good for a country; for great remembrances found the existence of nations as well as families, and are the most noble sources of patriotism….

Many cities of Italy had arrived at a certain degree of civilization before the first crusade; but this civilization, born in the midst of a barbarous age, and spread amongst some isolated nations divided among themselves, had no power to obtain maturity. For civilisation to produce the salutary effects it is capable of, everything must at the same time, have a tendency to the same perfection. Knowledge, laws, morals, power, all must proceed together. This is what has happened in France; therefore must France one day become the model and center of civilization in Europe. The holy wars contributed much to this happy revolution, which may be seen even in the first crusade.

Questions: What myths of crusading are promoted in the passage, and how are these linked to national identity? Why, in Michaud’s opinion, is it important for Europeans (and in particular the French) to uphold and defend the Crusades? What connection does Michaud make between the Crusades and the politics and foreign policy of nineteenth-century France? Using evidence from elsewhere in the book, explain why medieval crusaders would or would not have agreed with the portraits of themselves and their opponents that Michaud paints in the first paragraph. What does Michaud mean when he states that “great remembrances found the existence of nations…and are the most noble sources of patriotism”? Is this why we study history today? How might his crusade history be read by Muslims then and now?

102. William Hillary’s Call for a New crusade

The nineteenth century witnessed a revival in the ideals of crusading knighthood and the military orders. Divisions of both the Knights Hospitallers of St. John and the Templars emerged in England during the first half of the century. These orders fused the romantic notions of chivalry with the agenda of “new” imperialism. Sir William Hillary (1771–1847), a knight of the English Order of St. John, had a varied career as personal attendant to the son of King George III, soldier, philanthropist (best known as the founder of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution), and writer of numerous pamphlets and essays. When it was reported that Acre had been taken by the sultan of Turkey in 1840, Hillary responded with a pamphlet entitled Suggestions for the Christian occupation of the Holy Land, as a Sovereign State, by the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Later in 1841 he also published An address to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, on the Christian occupation of the Holy Land, as a Sovereign State under their Dominion. Although this proposal for a new crusade failed to gain the required support, the pamphlets nevertheless demonstrate the alliance that was emerging between the popular crusading ideal and nineteenth-century imperialism.

Source: William Hillary, Suggestions for the Christian occupation of the Holy Land, as a Sovereign State, by the Order of St. John of Jerusalem (London, 1841), pp. 3–8.

The Christian occupation of the Holy Land has, for many centuries, been the most momentous of any subject which has ever engaged the attention of mankind. Nearly a thousand years ago it called forth the religious and warlike enthusiasm of the Christian and the Moslem through almost every region of Europe and of Asia. This great contest occupied a longer space of time—called more numerous armies into the field—produced a greater display of chivalric and hardy valor, but attended with the most appalling sacrifice of blood and treasure, of any cause in which human ambition, enthusiasm, or superstition were ever engaged.

From the first crusade to the conquest of Jerusalem by Godfrey Bouillon, in 1099, millions on both sides perished in the sanguinary contest. The Christian monarchy in Palestine was one continued scene of foreign war or desperate contest during the 88 years in which its kings occupied their precarious throne, until worn out by the perpetual drain upon the valor and the treasure of the European princes, whose jealousies of each other prevented them from acting with united energy, and hard pressed by the warlike and ambitious Saladin, Jerusalem was lost, and the Saracens over-ran the Holy Land, which even the super-human valor of our lion-hearted king could not recover, though his brilliant deeds of arms placed his renowned name at the head of the chivalry of Christendom.

From that period the great military Orders of St. John of Jerusalem, the Templars, and the Teutonic knights, in many a bloody field desperately defended all which remained of a Christian name in Palestine, until St. John of Acre was taken, after the three Grand Masters [of ] those Orders had fallen in battle, and their gallant knights were almost exterminated.

This the crusades may be said to have terminated, after a most desperate and devastating struggle of many centuries, and all for which Christian zeal and enthusiasm had so long contended has to the present day remained under the Mohammedan yoke, and the Christians and the Jews have never since been more than tolerated sojourners in the Holy Land, subjected in their devotional pilgrimages to the caprice, the extortion, and the oppression of the despotic satraps by which it has in succession been ruled.

But in these eventful times in which we live, how wonderfully have the scenes changed! And after a lapse of six centuries we once more see the standards of England and Austria floating over the walls of St. John of Acre, that renowned fortress so gallantly taken and so long defended in the olden time by the redoubted chivalry of Europe against the Saracens, and more recently by the heroic Sir Sidney Smith against that mixture of all faiths, led by Napoleon in person, only to be repulsed from before its walls.

But now we see the crescent standard of the Sultan also displayed on its towers, side by side with the proud banners of England and her allies; and are we then to witness Acre and the Holy Land wrested by Christian prowess from the infidel Pacha of Egypt to be delivered up to the Sultan Sovereign of the Mohammedan creed? Only recently England, France, and Russia took Greece from the Turk to place a Christian king upon its throne; but Syria, with as large a population of Christians as Greece, we conquer from one infidel to give it up to another….

It seems universally agreed that Syria must not be restored to the Egyptians, and all almost equally agree that the dominions of Mehemet Ali and those of the Sultan, at least on the shores of the Mediterranean, in order to prevent perpetual hostilities, ought to be separated by some third power; and does it not inevitably follow that this third power should be a Christian state?

To this project the complicated politics of Christendom might raise up almost insuperable obstacles to a sufficient union and co-operation in such a measure, and it might prove difficult to agree from what Christian church, and from what nation such Sovereign should be chosen.

To obviate these difficulties let the Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem be restored to its original splendor. Let it be patronized and supported by all the great powers of Christendom, and remodelled where necessary and practicable to suit the important occasion. And let the Pachalics of Gaza, of Acre (in which are situated Jerusalem and other places celebrated in sacred history) and, perhaps, the mountain regions of Christian Lebanon be placed under their Sovereign Rule, paying only a stipulated and certain annual revenue to the Sultan, and let the perpetual neutrality and possession be solemnly guaranteed to the Order, not only by all the Christians, but also the Mohammedan powers, and in return the further integrity of his remaining dominion should be equally secured to the Sultan; but to remove all jealousies, and to avoid a too great preponderance to France, by her having, at present, three separate langues [divisions] of the Order, it would become requisite that each of the great European monarchies, who were parties to this measure, should possess one langue; varying in the respective number of knights according to the relative importance of the several powers….

Under such an arrangement the strong claims of the descendants of the houses of Judea and Israel on their fatherland should be met in the most magnanimous manner. In Palestine it is not enough that their faith should be tolerated; they should have their religion, their temples, their rites, and usages guaranteed to them, as citizens of a free state; the Mohammedan should have his mosque, his religion, and his rights firmly secured. And every sect of the Christian faith should have equal laws and equal rights under the sovereign rule of the Order of St. John….

At this extraordinary crisis of the affairs of the East, this great question each day forces itself with increased interest on the minds and feelings of almost every Christian people, accompanied by the deepest anxiety that this most auspicious moment may not be lost, but that one common effort should be made to stimulate the powers, parties to the Treaty of the 15th of July last, in conjunction with France, to establish the Holy Land as a Christian and a Sovereign State, upon the most firm and permanent foundation, by which, above every other measure, would be secured the peace and happiness of the Christian and Mohammedan world….

The Emperors of Austria and Russia, the King of the French, and many illustrious Sovereigns and Princes of Europe, are already members of the order of St. John of Jerusalem; it therefore may be permitted to conclude, that a measure that would conduce so highly to its dignity, and at the same time secure the ascendency of the Christian name in the Holy Land, would have their cordial and powerful support.

The restoration of the order of St. John to its former state and dignity—of once more becoming the protector and defender of Palestine, appears to be the great connecting link in that chain, through which alone, perhaps, could the contending and conflicting interests of so many great and powerful nations be brought cordially to adopt any one measure as common to all. On this comprehensive scale might be based those mutual arrangements to which France would feel it, in accordance with her honor and her interests warmly to accede, as a member of this great Alliance; and thus that estrangement, which, after twenty-five years of peace, had unhappily arisen between that kingdom and the allies, might be effectually removed, and the affairs of the East and the balance of power in Europe be permanently and honorably adjusted, and secured on the principles calculated to endure, and long to avert the calamities of war from so many nations.

Questions: Compare Hillary’s call to crusade to that of Urban II. How does Hillary justify the West’s occupation of the Holy Land? How does Hillary’s vision compare with the medieval functions and character of the military orders? In what ways did the revival of the crusading ideal support the tenets of Western imperialism?

103. Sayyid ‘Ali Hariri’s Book of the Splendid Stories of the Crusades

So far this chapter’s documents have been heavily weighted in favor of the West. This is not, however, a consequence of editorial choice or lack of available English translations. As Carole Hillenbrand, a scholar of Islamic history notes, up until the middle of the nineteenth century, “Muslims showed little interest in the Crusades as a discrete entity.” Hillenbrand points out that the Arabic terms for the Crusades, “the Cross wars” or “the war of the Cross,” did not come into use until the mid-nineteenth century and even then were “European borrowings.”44 Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2000), pp. 591–92.

Normally, the Crusades were not set apart from other conflicts, nor did the Crusaders merit any distinguishing identity other than the ethnic tag of “Franks” (Faranj). Initial nineteenth-century Islamic histories were simply Arabic translations from European texts. However, in 1899 there appeared the first Arabic study of the Crusades—and one that made almost exclusive use of medieval Islamic documents. Kitab al-akhbar al-saniyah fi al-Hurub al-Salibiyah (Book of the Splendid Stories of the Crusades) was written by Sayyid ‘Ali Hariri, an Egyptian Muslim. This extract from his introduction demonstrates a growing awareness of the Crusades within the Islamic world. More importantly, we can see how harb al-salib (the war of the Cross) was beginning to be reevaluated in light of the political activity and growing hostility between East and West.

Source: Sayyid ‘Ali Hariri, Kitab al-akhbar al-saniyah fi al-Hurub al-Salibiyah (Cairo: al-Matba’ah al-’Umumiyah, 1899), p. 3, trans. John M. Chamberlin, in “Imagining Defeat: An Arabic Historiography of the Crusades,” unpublished MA Thesis (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2007), p. 29.

For what follows, the importance of the Crusades, which happened during the bygone era, is not hidden from everyone. The popes and clerics incited the people of Europe to attack the Muslims, and the crusaders hurried to seize Syria with the goal of removing Jerusalem from the hands of Islam. Following that came a unification of the Muslims and the removal of the Crusaders from the land and the difficulties, failures, ruin, and confusion that those Crusaders faced.

It is given that the kings of Europe are now colluding against our country (may God protect it) such that it resembles what those gone by had done. Therefore, our great [Ottoman] sultan, our most exalted Khakhan, he who is protected by the double lion, Abd al-Hamid II, said that Europe is once again waging a crusading war on us, in a political form. Since the community of Arabic readers don’t have a book in our language that encompasses the wars of the Crusades so that we can know the truth about them, though we can find bits about them in books of history, free of any information about their reasons, their intentions, their outcome, etc., I took up this book, which I named “The Splendid Stories of the Crusades.” I took a precise interest in writing this comprehensive book of the eight crusader wars, elucidating each of these wars singularly, clarifying its reasons and instigators and the travel of its military forces and what the crusaders did by way of fighting the Muslim kings. I have also clarified the history of the kings of Islam from the era of these wars who had interaction with the crusaders from the year 490 hijri until the year 690 hijri, in which the crusaders were driven out of Syria, in a simple manner, free of complexity and boring prolixity.

Questions: What, according to Hariri, is the purpose of his history? Who is its audience? How has Hariri’s notion of crusading history been shaped by the nineteenth-century revival of interest in the Crusades in Europe? How does he go about making the link between crusading and Western imperialism?

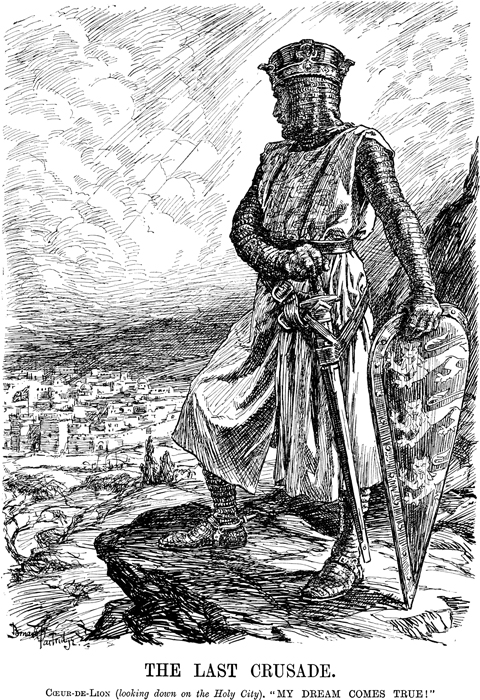

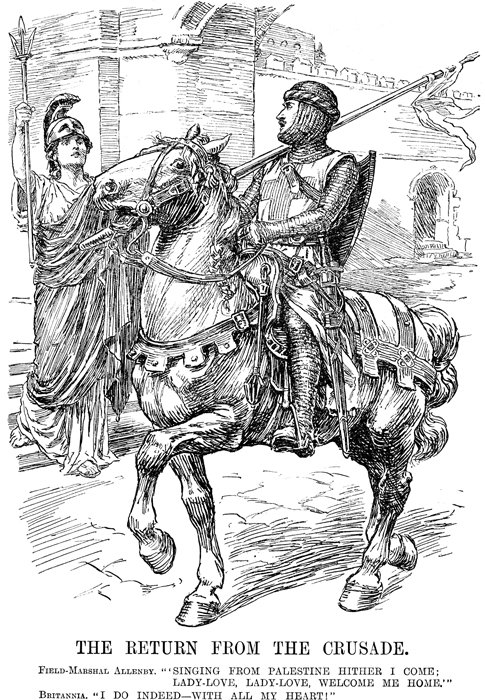

104. World War I Political Cartoons

World War I (1914–18) was fought partly in the Middle East, and by the end of the war the Ottoman Empire had been occupied and partitioned by the Western powers. In December 1917, the British general Edmund Allenby entered the city of Jerusalem as part of his campaign against the Turks. Crusading imagery and rhetoric had permeated the Allies’ promotion of the war, making the link between Allenby’s entrance and the crusade of Richard I a tempting comparison for the British press. Allenby himself was not keen to promote this connection and had deliberately entered on foot through the Jaffa Gate out of respect for the holy city. Declaring martial law, Allenby felt the need to reassure the city’s citizens by a proclamation promising the following:

…since your city is regarded with affection by the adherents of three of the great religions of mankind and its soil has been consecrated by the prayers and pilgrimages of multitudes of devout people of these three religions for many centuries, therefore, do I make it known to you that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred.

Back in Britain, however, the need for diplomacy was less pressing, as the cartoons below attest; both were published in Punch, a widely read weekly magazine. Allenby himself was not happy with the depiction, as many in his army were Muslim. Moreover, the British War Office felt compelled to issue a “Defence-notice” to the press, saying, “The attention of the Press is again drawn to the undesirability of publishing any article, paragraph or picture suggesting that military operations against Turkey are in any sense a Holy War or modern Crusade, or have anything whatever to do with religious questions.” This did not, however, stop the press from using crusading imagery or popular sentiment from responding to it, as the second Punch cartoon (1919) also shows.

Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd., www.punch.co.uk.

Source: Punch, or the London Charivari, Dec. 19, 1917, and Sept. 17, 1919. Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd., www.punch.co.uk.

Questions: What does each cartoon show, and what does each mean? What do they tell us of British views on the Crusades at the time of World War I? What accounts for the popularity of crusading imagery and rhetoric during this period? Why was the British press willing to use the crusading analogy despite the opposition of Allenby and the War Office?

105. Sayyid Qutb’s Social Justice in Islam And Muhammad Asad’s Islam at the Crossroads

The founding of the state of Israel in 1948 created new tensions in the Middle East. Sayyid Qutb (1906–66), a leading Islamic philosopher and political activist of this period, linked the West’s support of Israel with imperialism, which was itself intertwined with the “crusading spirit” (ruh salibiyya). For Qutb, this new crusade was not just a matter of political or military invasion, but also a religious and cultural offensive. Qutb wrote of “Crusaderism” (sulubbiya), by which he meant a process, driven by hatred that seeks to destroy Islam, Islamic society, and Muslims. This was also a time when the idea of pan-Islam, the concept of a world-wide Islamic society as opposed to the more traditional notion of Arab nationalism, was finding favor with Islamic political movements. Qutb was a member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, but he clashed with the Egyptian state and was imprisoned from 1954 to 1964. Rearrested in 1965, he was accused of plotting against the regime and executed in 1966. The passage below from Qutb’s Social Justice in Islam (1949) quotes extensively from Chapter 3 of Muhammad Asad’s Islam at the Crossroads (1934). Asad (1900–92) was the grandson of an orthodox Polish rabbi. He converted to Islam in 1926 and wrote on the dangers of Western culture to Islam and Muslims.

Source: Sayyid Qutb, Social Justice in Islam, trans. John B. Hardie; revised translation by Hamid Algar, rev. ed. (Oneonta, NY: Islamic Publications International, 2000), pp. 269–75.

But from that time [that is, of the Crusades] to this [Islam] has had to contend with ferocious enemies of the same spirit as the Crusaders, enemies both open and hidden.

But the final disaster to befall Islam took place only in the present age, when Europe conquered the world, and when the dark shadow of colonization spread over the whole Islamic world, East and West alike. Europe mustered all its forces to extinguish the spirit of Islam, it revived the inheritance of the crusaders’ hatred, and it employed all the materialistic and cultural powers at its disposal. Added to this was the internal collapse of the Islamic community, and its gradual removal over a long period from the teachings and injunctions of its religious faith.

When we speak of the hatred of Islam, born of the Crusading Spirit, which is latent in the European mind, we must not let ourselves be deceived by appearances, nor by their pretended respect for freedom of religion. They say, indeed, that Europe is not as unshakably Christian today as it was at the time of the Crusades and that there is nothing today to warrant hostility to Islam, as there was in those days. But this is entirely false and inaccurate. General Allenby was no more than typical of the mind of all Europe, when, entering Jerusalem during the First World War, he said: “Only now have the Crusades come to an end.” Similarly, the governor-general of the Sudan was no more than typical of the European mind when he placed all governmental power at the disposal of missionaries in the southern Sudan, while forbidding any Muslim trader even to pass through the country….

People sometimes wonder how this obstinate spirit of resistance to Islam can persist so strongly and to such a pitch in a Europe that has discarded Christianity, and where the exhortations of preacher and monk no longer fill European ears as they did in the age of the Crusades. But this fact ceases to be surprising when we take account of two facts:

1. [Quoted from Asad:] “The enmity that the Crusaders stirred up was not confined to the clangor of arms, but was, before all else and above all else, cultural enmity. The European mind was poisoned by the slurs which the Crusaders’ leaders cast on Islam as they spoke of it to their ignorant Western compatriots. It was in that age that there grew up in Europe the ridiculous idea that Islam was a religion of unbridled passion and violent sensuality, that it consisted merely of formal observances, and that it had no teaching of purity or of regeneration of heart. And this idea has remained as it has started….

“Thus was the seed of hatred sown. The ignorant mass of Crusaders had dependents in many places throughout Europe; and the process was hastened by the Spanish Christians in their war to deliver their country from ‘the yoke of the idolaters’…it took the form of a complete extirpation of Islam throughout Spain, after a persecution that reached a pitch of ferocity and bitterness hitherto unknown….

“But before the echoings of these happenings in Spain had died away, there took place a third event of immense significance, which was to hasten the breaking of ties between the Western world and Islam. This was the fall of Constantinople to the Turks. Europe had always looked to Byzantium as a relic of the glory of Greece and Rome and had regarded it as the fortress of Europe against Asiatic barbarism. Hence, with the fall of Constantinople the gate was thrown wide open to the flood of Islam. In the centuries that followed, and which were filled with wars, the hostility of Europe to Islam was no longer a question of merely cultural importance; it was now a question of political import also. And this fact further increased the violence of that hostility.

“Despite all this, Europe derived great profit from this conflict. The Renaissance or rebirth of European arts and sciences in the widest sense arose particularly from an Islamic and Arab source; in most cases it can be traced back to material contacts between the East and the West. Europe profited more than did the Muslim world, but it did not acknowledge the gift by lessening its loathing of Islam. Or, more correctly, the reverse is true, that loathing increased with the passage of time until it was second nature…. Then followed the age of the Reformation, during which Europe was divided into various sects, each continually employed in arming itself against every other; yet hostility to Islam was the common feature of all of them. This in turn was followed by an age when religious feeling started to subside, but the hostility to Islam continued unabated. One of the clearest proofs of this is that the French philosopher Voltaire was one of the bitterest critics of Christianity and of the Church in the eighteenth century; yet he was at the same time violently hostile to Islam and its Messenger. A few score years later came the age in which Western scholars commenced to study foreign cultures and to regard them with a measure of sympathy. Yet in all matters connected with Islam the traditional dislike began to creep under the form of partisan spirit which was not conductive to academic study. Thus the gulf that history had dug between Europe and the Islamic world remained still unbridged. Dislike of Islam thus became a fundamental part of European thinking…. Hence the attacks made by Orientalists upon Islam betray an inherited instinct and a peculiarity of nature; they are based on an impression created by the Crusades and shaped by all the mental influences of these on the early Europeans…. Despite the fact that the religious convictions that gave rise to European hostility to Islam have now lost their power and been replaced by a more materialistic form of life, yet the ancient antipathy itself still remains as a vital element within the European mind. So far as the strength of this antipathy is concerned, it undoubtedly varies from one individual to another, but that it exists is indisputable. The spirit of the Crusades, though perhaps in a milder form, still hangs over Europe; and that civilization in its dealings with the Islamic world still occupies a position that bears clear traces of that genocidal force.”

2. European imperial interests can never forget that the spirit of Islam is like a rock blocking the spread of imperialism. This rock must either be destroyed or pushed aside….

Islam is at once a spiritual power and an incentive to material power, it is at once a form of opposition in itself and an incentive to a still more forcible opposition. Therefore European imperialism cannot but be hostile to such a religion…. Thus each imperialist state has proceeded by one means or another to oppose and to throttle Islam since the last century [that is, the nineteenth], and even before that. And that they still proceed to do essentially the same thing in concert is obvious from the position taken up by the Western nations on the question of Indonesia and Holland; on that of Kashmir, India and Pakistan; and on that of Hyderabad, India and the Nizam. Finally the same thing is supremely evident in the position on Palestine.

There are those who hold that it is the financial influence of the Jews in the United States and elsewhere that has governed the policy of the West. There are those who say that it is English ambition and Anglo-Saxon guile that are responsible for the present position. And there are those who believe that it is the antipathy between the Eastern [that is, communist] and Western blocs that is responsible. All these opinions overlook one vital element in the question, which must be added to all other elements, the Crusader spirit that runs in the blood of all Occidentals.

Questions: How accurate is Qutb’s assessement of historical crusading? What does Qutb see as the failings of modern Islamic society? How do Qutb and Asad account for what they see as the development of Crusaderism (the hatred of Islam and desire to see it eradicated) through the centuries? Why, in their opinion, can these two sides not be reconciled? To what extent are these arguments taken up by today’s radical Islamists?

106. The Hamas Covenant

The latter half of the twentieth century saw an escalation in hostilities between Palestinians and Israelis, resulting in the creation of activist, radical groups on each side. While many of these movements began with purely political agendas, over time most came to identify themselves more with their respective religions. The organization known as Hamas has its origins in the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood and emerged as an active movement in response to the Palestinian uprising (intifada) of 1987. Seeking an Islamic state within the whole territory of Palestine, Hamas cites the argument that Palestine has for eleven of the last twelve centuries been controlled by Muslims, excepting the crusader period. The role of Europe and the United States in supporting the state of Israel is seen by Hamas as proof of the West’s continuing crusading imperialism, and this issue is highlighted in article 15 of the Covenant issued by Hamas in 1988.

Source: Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement” (1988), translated by Yale Law School Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu.

The day that enemies usurp part of Moslem land, Jihad becomes the individual duty of every Moslem. In face of the Jews’ usurpation of Palestine, it is compulsory that the banner of Jihad be raised. To do this requires the diffusion of Islamic consciousness among the masses, both on the regional, Arab and Islamic levels. It is necessary to instil the spirit of Jihad in the heart of the nation so that they would confront the enemies and join the ranks of the fighters.

It is necessary that scientists, educators and teachers, information and media people, as well as the educated masses, especially the youth and sheikhs of the Islamic movements, should take part in the operation of awakening [the masses]. It is important that basic changes be made in the school curriculum, to cleanse it of the traces of ideological invasion that affected it as a result of the orientalists and missionaries who infiltrated the region following the defeat of the Crusaders at the hands of Salah el-Din [Saladin]. The Crusaders realised that it was impossible to defeat the Moslems without first having ideological invasion pave the way by upsetting their thoughts, disfiguring their heritage, and violating their ideals. Only then could they invade with soldiers. This, in its turn, paved the way for the imperialistic invasion that made Allenby declare on entering Jerusalem: “Only now have the Crusades ended.” General Guru stood at Salah el-Din’s grave and said: “We have returned, O Salah el-Din.” Imperialism has helped towards the strengthening of ideological invasion, deepening…its roots. All this has paved the way towards the loss of Palestine.

It is necessary to instil in the minds of the Moslem generations that the Palestinian problem is a religious problem, and should be dealt with on this basis. Palestine contains Islamic holy sites. In it there is al-Aqsa Mosque which is bound to the great Mosque in Mecca in an inseparable bond as long as heaven and earth speak of Isra’ [Mohammed’s midnight journey to the seven heavens] and Mi’raj [Mohammed’s ascension to the seven heavens from Jerusalem]….

Questions: Who is the intended audience of this declaration? What role does education play in Hamas’s religious and political goals? How does Hamas link the crusading period to its current campaign? What is the nature of the jihad proposed in the Covenant, and what is used to motivate followers to this cause?

107. Pope John Paul II’s Statements about Past Christian Actions

Events of the late twentieth century alerted many in the West to the growing gap between traditionally Islamic and Christian states. Western involvement in Middle Eastern wars and attacks on Western targets by radical Islamist groups were, for some, a wake-up call to the deteriorating state of East–West relations. It was during this period that the Catholic Church instigated an International Theological Commission to consider the “faults of the past,” including wrongs committed against non-Catholics. The commission was set up in 1999 under the direction of the then-Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) and resulted in the Day of Pardon presided over by Pope John Paul II in March 2000. Neither the study nor the papal liturgy refers to the Crusades by name (or indeed to the Holocaust), but most agree that these events were very much in the minds of the comissioners and the pope. The second document below begins in the middle of the pope’s homily, or short sermon, during the Day of Pardon church service. The Greek words “Kyrie, eleison” mean “Lord, have mercy.”

Source: International Theological Commission, “Memory and Reconciliation: The Church and the Faults of the Past” (December 1999), trans. at http://www.vatican.va; “Day of Pardon” (March 2000), from the University of Waterloo Public Apology Database, Church Apologies: http://ccmlab.uwaterloo.ca/pad/church.html#JP2day.

Memory and Reconciliation: The Church and the Faults of the Past

5.3. The Use of Force in the Service of Truth

To the counter-witness of the division between Christians should be added that of the various occasions in the past millennium when doubtful means were employed in the pursuit of good ends, such as the proclamation of the Gospel or the defence of the unity of the faith. [As Pope John Paul II previously wrote in his Apostolic Letter Tertio millennio adveniente,] “Another sad chapter of history to which the sons and daughters of the Church must return with a spirit of repentance is that of the acquiescence given, especially in certain centuries, to intolerance and even the use of force in the service of truth.” This refers to forms of evangelization that employed improper means to announce the revealed truth or did not include an evangelical discernment suited to the cultural values of peoples or did not respect the consciences of the persons to whom the faith was presented, as well as all forms of force used in the repression and correction of errors.

Analogous attention should be paid to all the failures, for which the sons and daughters of the Church may have been responsible, to denounce injustice and violence in the great variety of historical situations [as the pope stated in a general audience in September 1999]: “Then there is the lack of discernment by many Christians in situations where basic human rights were violated. The request for forgiveness applies to whatever should have been done or was passed over in silence because of weakness or bad judgement, to what was done or said hesitantly or inappropriately.”

As always, establishing the historical truth by means of historical-critical research is decisive. Once the facts have been established, it will be necessary to evaluate their spiritual and moral value, as well as their objective significance. Only thus will it be possible to avoid every form of mythical memory and reach a fair critical memory capable—in the light of faith—of producing fruits of conversion and renewal. [In the words of the same Apostolic Letter,] “From these painful moments of the past a lesson can be drawn for the future, leading all Christians to adhere fully to the sublime principle stated by the [Second Vatican] Council: ‘The truth cannot impose itself except by virtue of its own truth, as it wins over the mind with both gentleness and power.’”

Pope John Paul II’s “Day of Pardon”

3. Before Christ who, out of love, took our guilt upon himself, we are all invited to make a profound examination of conscience. One of the characteristic elements of the Great Jubilee is what I [have previously] described as the “purification of memory”…. As the Successor of Peter, I asked that “in this year of mercy the Church, strong in the holiness which she receives from her Lord, should kneel before God and implore forgiveness for the past and present sins of her sons and daughters.” Today, the First Sunday of Lent, seemed to me the right occasion for the Church, gathered spiritually round the Successor of Peter, to implore divine forgiveness for the sins of all believers. Let us forgive and ask forgiveness! This appeal has prompted a thorough and fruitful reflection, which led to the publication several days ago of a document of the International Theological Commission, entitled: “Memory and Reconciliation: The Church and the Faults of the Past.” I thank everyone who helped to prepare this text. It is very useful for correctly understanding and carrying out the authentic request for pardon, based on the objective responsibility which Christians share as members of the Mystical Body, and which spurs today’s faithful to recognize, along with their own sins, the sins of yesterday’s Christians, in the light of careful historical and theological discernment. Indeed, [in the words of an earlier declaration,] “because of the bond which unites us to one another in the Mystical Body, all of us, though not personally responsible and without encroaching on the judgement of God who alone knows every heart, bear the burden of the errors and faults of those who have gone before us.” The recognition of past wrongs serves to reawaken our consciences to the compromises of the present, opening the way to conversion for everyone.

4. Let us forgive and ask forgiveness! While we praise God who, in his merciful love, has produced in the Church a wonderful harvest of holiness, missionary zeal, total dedication to Christ and neighbor, we cannot fail to recognize the infidelities to the Gospel committed by some of our brethren, especially during the second millennium. Let us ask pardon for the divisions which have occurred among Christians, for the violence some have used in the service of the truth and for the distrustful and hostile attitudes sometimes taken towards the followers of other religions. Let us confess, even more, our responsibilities as Christians for the evils of today. We must ask ourselves what our responsibilities are regarding atheism, religious indifference, secularism, ethical relativism, the violations of the right to life, disregard for the poor in many countries. We humbly ask forgiveness for the part which each of us has had in these evils by our own actions, thus helping to disfigure the face of the Church. At the same time, as we confess our sins, let us forgive the sins committed by others against us. Countless times in the course of history Christians have suffered hardship, oppression and persecution because of their faith. Just as the victims of such abuses forgave them, so let us forgive as well. The Church today feels and has always felt obliged to purify her memory of those sad events from every feeling of rancor or revenge. In this way the Jubilee becomes for everyone a favorable opportunity for a profound conversion to the Gospel. The acceptance of God’s forgiveness leads to the commitment to forgive our brothers and sisters and to be reconciled with them….

Solemn Prayer of the Faithful Confessing Sins and Requesting God’s Pardon

The Holy Father: Brothers and Sisters, let us turn with trust to God our Father, who is merciful and compassionate, slow to anger, great in love and fidelity, and ask him to accept the repentance of his people who humbly confess their sins, and to grant them mercy.

(All pray for a moment in silence.)…

II. Confession of Sins Committed in the Service of Truth

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger: Let us pray that each one of us, looking to the Lord Jesus, meek and humble of heart, will recognize that even men of the Church, in the name of faith and morals, have sometimes used methods not in keeping with the Gospel in the solemn duty of defending the truth.

(Silent prayer.)

The Holy Father: Lord, God of all men and women, in certain periods of history Christians have at times given in to intolerance and have not been faithful to the great commandment of love, sullying in this way the face of the Church, your Spouse. Have mercy on your sinful children and accept our resolve to seek and promote truth in the gentleness of charity, in the firm knowledge that truth can prevail only in virtue of truth itself. We ask this through Christ our Lord.

Response: Amen. Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison. (A lamp is lit before the Crucifix.)…

IV. Confession of Sins against the People of Israel

Cardinal Edward Cassidy: Let us pray that, in recalling the sufferings endured by the people of Israel throughout history, Christians will acknowledge the sins committed by not a few of their number against the people of the Covenant and the blessings, and in this way will purify their hearts.

The Holy Father: God of our fathers, you chose Abraham and his descendants to bring your Name to the Nations: we are deeply saddened by the behavior of those who in the course of history have caused these children of yours to suffer, and asking your forgiveness we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant. We ask this through Christ our Lord.

Response: Amen. Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison.

(A lamp is lit before the Crucifix.)

V. Confession of Sins Committed in Actions against Love, Peace, the Rights of Peoples, and Respect for Cultures and Religions

Archbishop Stephen Fumio Hamao: Let us pray that contemplating Jesus, our Lord and our Peace, Christians will be able to repent of the words and attitudes caused by pride, by hatred, by the desire to dominate others, by enmity towards members of other religions and towards the weakest groups in society, such as immigrants and itinerants.

(Silent prayer.)

The Holy Father: Lord of the world, Father of all, through your Son you asked us to love our enemies, to do good to those who hate us and to pray for those who persecute us. Yet Christians have often denied the Gospel; yielding to a mentality of power, they have violated the rights of ethnic groups and peoples, and shown contempt for their cultures and religious traditions: be patient and merciful towards us, and grant us your forgiveness! We ask this through Christ our Lord.

Response: Amen. Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison.…

Questions: For what actions and individuals are the church officials seeking “pardon” and “reconciliation” in these writings and rituals? What is their reasoning for doing so? Compare the stance of the medieval church of the crusading period toward non-Christians with that of the Commission on this issue. Why do you think the document avoided referring to the Crusades by name? How are the Crusades generally viewed today by mainstream Christian organizations?

108. Crusading Rhetoric after 9/11

On 11 September 2001, the terrorist group Al Qaeda hijacked four airplanes in the US, flying two of them into the World Trade Center twin towers, one into the Pentagon, and the last into a field in rural Pennsylvania. The loss of life numbered in the thousands. These events prompted much debate on the nature of East–West and Christian–Muslim relations and the perceived history of conflict and coexistence between these entities. It can be argued that their respective views on the Crusades also played a part in the polarization of these two cultures. By the turn of the twenty-first century, some in the Muslim community had developed a fixed definition of crusading, linking it closely to imperialism and the West’s hostility toward the Islamic religion. The West, on the other hand, had seen the term broaden to encompass any number of causes or events that were deemed to be morally right. Much has been made of President George W. Bush’s use of the term “crusade” in his response to the 9/11 attacks. The documents below relate to this event and reactions to it. Osama bin Laden was the head of Al Qaeda.

Source: George Bush’s remarks quoted in the White House archives: http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010916-2.html; Ari Fleischer, White House Press Briefing (September 18, 2001), from The American Presidency Project: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu; Raymond Ibrahim, The Al Qaeda Reader (New York: Doubleday, 2007), pp. 272–73.

US President George Bush’s Informal Remarks to Reporters on 16 September 2001

…We need to go back to work tomorrow and we will. But we need to be alert to the fact that these evil-doers still exist. We haven’t seen this kind of barbarism in a long period of time. No one could have conceivably imagined suicide bombers burrowing into our society and then emerging all in the same day to fly their aircraft—fly U.S. aircraft into buildings full of innocent people—and show no remorse. This is a new kind of—a new kind of evil. And we understand. And the American people are beginning to understand. This crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while. And the American people must be patient. I’m going to be patient.

But I can assure the American people I am determined, I’m not going to be distracted, I will keep my focus to make sure that not only are these brought to justice, but anybody who’s been associated will be brought to justice. Those who harbor terrorists will be brought to justice. It is time for us to win the first war of the twenty-first century decisively, so that our children and our grandchildren can live peacefully into the twenty-first century.

White House Press Briefing by Ari Fleischer, White House Press Secretary, on 18 September 2001

Q: The other question was, the President used the word crusade last Sunday, which has caused some consternation in a lot of Muslim countries. Can you explain his usage of that word, given the connotation to Muslims?

Mr. Fleischer: I think what the President was saying was—had no intended consequences for anybody, Muslim or otherwise, other than to say that this is a broad cause that he is calling on America and the nations around the world to join. That was the point—purpose of what he said.

Q: Does he regret having used that word, Ari, and will he not use it again in the context of talking about this effort?

Mr. Fleischer: I think to the degree that that word has any connotations that would upset any of our partners, or anybody else in the world, the President would regret if anything like that was conveyed. But the purpose of his conveying it is in the traditional English sense of the word. It’s a broad cause.

Osama bin Laden’s Response to President Bush’s Use of the Word “Crusade” (2001 and 2004)

October 2001

Our goal is for our nation to unite in the face of the Christian Crusade. This is the fiercest battle. Muslims have never faced anything bigger than this. Bush said it in his own words: “crusade.” When Bush says that, they try to cover up for him, then he said he didn’t mean it. He said “crusade.” Bush divided the world into two: “either with us or with terrorism.” Bush is the leader: he carries the big cross and walks. I swear that everyone who follows Bush in his scheme has given up Islam and the word of the Prophet. This is very clear. The Prophet has said, “Believers don’t follow Jews or Christians.” Our ulema [Muslim scholars trained in Islam and Islamic law] have said that those who follow the infidels have become infidels themselves. Those who follow Bush in his crusade against Muslims have denounced Allah…. This is a recurring war. The original crusade brought Richard [the Lionheart] from Britain, Louis from France, and Barbarous [that is, Frederick Barbarossa] from Germany…. Today the crusading countries rushed as soon as Bush raised the cross. They accepted the rule of the cross. What do Arab countries have to do with this Crusade? Everyone that supports Bush, even with one word, is an act of great treason.

November 2001

Bush has used the word “crusade.” This is a crusade declared by Bush….

Questions: Did President Bush’s understanding and use of the term “crusade” match that of most Westerners at the time of 9/11? Why was the West unaware of the sensitivity of the term and its implications for Muslims? How was Bush’s remark used by Al Qaeda to promote its agenda? Can you think of other examples of the use of the word “crusade” similar to how it is used above and in other contexts? How does Osama bin Laden use the words “cross” and “crusade,” and to what purpose?

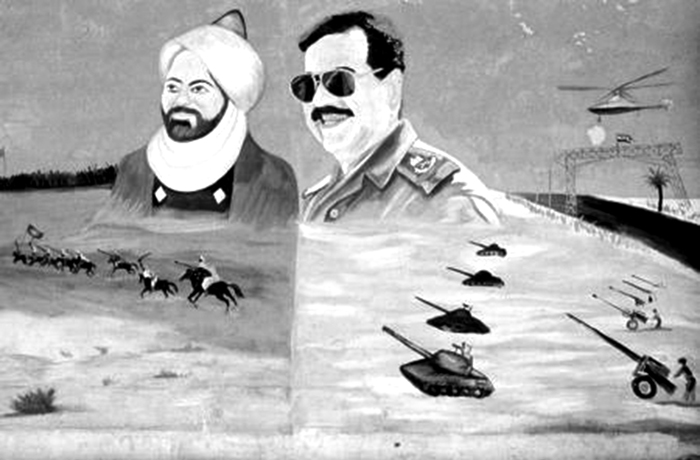

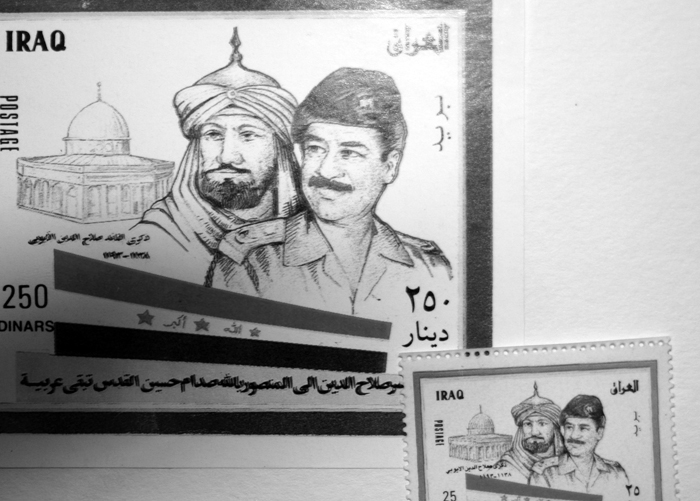

109. Modern Use of Images of Saladin