MARVILLE

I

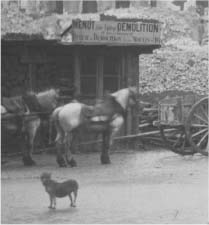

THE PHOTOGRAPH shows the back end of a Paris square, early on a summer morning, when the noises and smells of the city are still gathering their strength. The time of day can be deduced from the light, which falls from the east, the shadow of the building behind the camera, which has already cleared half the square, and the cleanness of the cobbles. The sun is up, but no one is about, except of course the photographer and his assistant.

The picture was taken in 1865, which is hard to believe, given the glassy clarity of the shot. There is more detail per square inch than seems possible for the period. Here at the dawn of the visible past, the buildings look almost radiant in their grime, as though they haven’t yet learned how to pose for a camera.

This is a real neighbourhood, scoured and crannied with habits and ambitions. Two or three splats of horse manure are visible on the cobbles, like blobs of paint on a canvas. A zoologist could probably identify the animal’s diet, estimate its speed across the square and even guess its breed and colour, if the droppings are consistent with the small grey horses that are waiting in front of a low building, hitched to removal carts, patiently enough for their heads to be only slightly blurred. Otherwise, the square is clean. The crossing sweepers have come and gone. In a poem written four years before this photograph was taken, Baudelaire remembered walking across a deserted square

…at the hour when the cleaning crews

Send their dark storms swirling into the silent air.

On the corner of one of the two narrow streets that run away to the west, a grey blur might be a dust-devil raised by the sweepers, or perhaps just the albumen-and-collodion ghost of someone hurrying from the scene into the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts.

The odd shape of the square commemorates something that no longer exists. The church of Saint-André was one of only two churches in Paris that were entirely separate from the surrounding buildings. It was sold during the Revolution and removed like an unwanted growth, leaving only the space it had occupied for six hundred years. Somewhere near the spot where the photographer has set up his tripod, a crying infant was held over a font and baptized François-Marie Arouet (he later rechristened himself Voltaire). The masonry remains like some ancient volcanic surge when the softer stone has been eroded.

Now, the walls that used to see nothing but other walls are festooned with letters from every page of a typesetter’s sample book, as numerous as the cartouches in an Egyptian tomb. Fifty feet in the air, a giant invalid lies on a mechanical bed that can be hired or purchased at 28 Rue Serpente. The forty-centime baths around the corner in the Rue Larrey are in competition with the more distant but sophisticated steam baths at 27 Rue Monsieur-le-Prince.

Even if the date of the photograph were unknown, it could still be deduced from the addresses on the advertisements: the greater the distance, the later in time. In 1865, no one is expected to go shopping in streets across the river. A person could stand where the photographer stood and compose a comprehensive shopping list. She could buy some glass for a broken window, some wallpaper and furniture – or a piece of leather for the armchair – and hire a removal cart (from M. Mondet) to take away the items that were damaged by the rain. M. Robbe (5 Rue Gît-le-Cœur) could repair the window frame, and M. Geliot at no. 24 could check the lead flashing and the zinc roofing. She could buy a print engraving (a Notre-Dame is displayed in the furniture-shop window), and a new piece of porcelain or crystal from A. Desvignes. She could order some coal and some wine (also from M. Mondet), buy a cheese at the crémerie and a book to read by the fire. She need never leave the quartier.

So much information is contained in that split-second burst of photons that if the glass plate survived a holocaust and lay buried under rubble for centuries in a leather satchel, there would be enough to compile a small, speculative encyclopedia of Paris in the late second millennium. It might even contain some pieces of information that were missing from encyclopedias published while the city still existed. If the middle section of M. Robbe’s advertisement for firewood had not come adrift, we might never have known that some of those words were not painted on the walls but printed on rainproof cloth and hung up like backdrops.

Few writers even mention this ubiquitous plague of advertising. A single phrase in Baudelaire’s notebook is almost the only surviving evidence of its impact: ‘Immense nausée des affiches’ – an overdose of advertising, or a bad case of publicity sickness. Imagine a poet testing words in his mind, measuring rhythms with his feet, bombarded with verbless phrases. As a teenager, he walked the streets of his native city,

…stumbling upon words as on the paving-stones,

Sometimes bumping into lines I’d dreamt of long before.

Now, there are pavements, like the one in front of the glassware depository, with proper kerbs and gutters. There is no longer any excuse for stumbling. Baudelaire has taken to writing poems in prose. The art lover who grew up with the smell of his father’s oil paints has begun to look at photographs, and even to savour their ‘cruel and surprising charm’. He probably knows the photographer, and he certainly knows his work, but Charles Marville usually sends an associate to exhibitions. He keeps his techniques and his friendships to himself. He feels quite at home in a city devoid of people, at the hour when the sun shines for no one but himself and his assistant.

By the time the removal carts have trundled off, and the chairs outside the wine-shop are occupied, the photographer and his assistant will be back in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, on the aerial terrace at 27 Rue Saint-Dominique, photographing the vast pageant of clouds, the airborne battalions that are several times wider than a city, bound for some indefinable realm beyond the suburbs.

WITH THE SKIES’ rippling explosion still developing on his retina, Marville leaves the terrace and retreats into the studio where the light is purple and umber. There are stained-glass windows and dark oak cupboards. The wallpaper is embossed with sombre vegetation. The assistant carefully removes the pane of collodion-coated glass from the wooden frame. At this stage of the process, the glass appears quite blank. Then he pours on the solution of pyrogallic acid and ferrous sulphate, and, by some chemical trick for which science has no explanation, the light from the morning square turns the silver into reality.

This alchemy-in-reverse always amazes him. It looks like a pristine, miniature city from which the inhabitants have fled, a neighbourhood after the plague or a chemical bomb dropped from a balloon. There are traces of human life but no people. His assistant plunges the plate into the gold chloride to darken the tones. Marville watches the young man’s dark hair fall across his cheek-bone as he bends over the porcelain basin. The assistant washes the negative and fixes the image with cyanide of potassium. Words appear as though they were printed on the plate before it was exposed to the light: BAINS d’EAU; LITS & FAUTEUILS; COMMERCE DE VINS.

He sees the quartier caught unawares. This is the square en déshabillé, in its own private time zone, a section of abandoned city with all its interiors intact. He is pleased by the evident chaos of misaligned walls, the stain-trails of rainwater, the patched-up render, the slump of the house-fronts, the dislocated cobbles and the absence of people. The only vehicles are the removal carts: perhaps, behind one of the windows, someone is gathering together her belongings.

The image joins the other prints that are waiting to be framed for the exhibition: four hundred and twenty-five pictures of a magical, vacant metropolis called Marville. The Emperor will see the dingy peristyles and the crumbling pylons, and be reminded of his uncle’s expedition to Egypt, the monuments to vanished gods, frozen in the desert. He might wonder how much of Paris he has really seen, and how anyone can be said to govern a city so full of secrets.

IN THE STUDIO, the light grows darker as the sun grows more insistent. The assistant tightens the latch on the shutters, and makes certain that the curtains overlap.

When photography was still a sideshow on the boulevard, Marville set up his easel in the Forest of Fontainebleau. He drew empty landscapes for magazines and illustrated storybooks – Paul et Virginie, The Banks of the Seine, The Arabian Nights – and left his colleague to insert the human figures. His own figures were always clumsy and incongruous. Now, he finds his solitude in Paris, on expeditions with his assistant. Certain times of day are more suitable than others, but the time of day can be lengthened indefinitely, divided up into fractions of seconds.

Fresh coffee helps to neutralize the smell of ammonium and varnish; it concentrates the mind. These days, only an old-fashioned artist with a paint-spattered smock would use alcohol to stimulate his brain and to steady his hand. The silken slip of albumen paper is laid on the proof. The slightest defect will be visible – a mote of dust, a speck of tripoli stone, a furtive sunbeam.

The scene glows red (an effect of the albumen) until the final washing. The print is rinsed, dried and pressed. A light coat of wax and mastic is applied. The assistant places the print on the table and stands back like a painter from his easel.

Marville takes a magnifying-glass: his eye wanders from window to window, looking for the familiar pattern of smudges. It takes a long time to explore the scene…At last, he sees them: they might be mistaken for imperfections on the plate, and even at this level of precision, it is hard to be sure. A slightly stooping form in a long, grey coat is entering the crémerie. At the window between the Bains d’Eau and the Bains de Vapeur, a pale circle bisected by the railing, and a patch of light beneath, might be someone holding a bowl of coffee, looking out at the two photographers in the square below. There is so much clutter in the scene that these wan blotches are barely noticeable.

He sits up now and surveys the whole picture. This time, he realizes that it has an unexpected focal point – the little balcony on wooden struts, high above the wine shop, level with the invalid on the orthopedic bed. A shed with six windows and a stovepipe – it might almost have been transplanted from some outlying village – leans against a whitewashed wall that might almost be a cottage. A long pole is propped on the railings to keep open a skylight in the tiled roof. Six box shrubs have been arrayed in pots, and there, to the left of the little hedge, a figure bends over a piece of work. It might just be a rag that looks like a head of grey hair, but it has a certain distracting poignancy.

The figure could be removed with a paintbrush dipped in India ink and a gum solution. This is how some photographers eradicate splotches on a face or a sleeve. But he likes the way in which the camera turns a human form into something small and fleeting, like a puddle on the cobbles or a reflection on a windowpane.

The varnished print is left to dry. Marville spends the afternoon indoors with his assistant. He photographs him from behind, poring over prints in the studio. He photographs him with his shock of black hair, reclining on the terrace with chimney-pots in the background, like a Nubian lion or a Paris alley-cat. He photographs him in close-up, as delicately as though his face were a row of buildings, with his marble forehead and the slender balconies of his eyebrows under the stormy sky of his hair. It might be the portrait of a poet, with almond eyes and cruel lips, lit beautifully like the square in the morning sun.

II

IN HIS OFFICIAL OFFICE above the Seine – not the private study next to his bedroom, but the state room with three large windows looking onto the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville – the model inhabitant of New Paris sits at a large desk. It is, without a shadow of a doubt, a glorious morning. His shoes are spotless; he is breathing easily. No one has arrived late for work. A statistic can be brought to him within minutes. A garden of Mediterranean shrubs and sub-tropical flowers separates his building from the river.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann almost dwarfs his desk, which occupies the centre of the room. When he wears his medals, as he does today, his chest looks like an expensive apartment block. He can imagine – he has seen enough caricatures of Baron Haussmann the demolition man, the trowel-wielding beaver, the monumental henchman of Napoleon III – his forehead supported by caryatids. When the Emperor arrives, he will have to stoop to compensate for the difference in height.

Behind him, mounted on rolling frames, the specially engraved 1:5000 map of Paris (not sold in shops) stands ready to be wheeled into the light. It forms his backdrop when he sits at the desk. He often turns around and becomes absorbed in it. Notre-Dame, which is now exposed and visible across the river, precisely where it ought to be in relation to everything else, is the size of his thumbprint; the rectangle of the Louvre and the Tuileries is contained within the compass of his index finger and his pinkie.

He looks down at the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville and sees the accelerated movement of carriages across the square. He understands the flow of traffic, the vents and flumes of intersections, the multiple valves of his radiating, starry squares, of which there are now twenty-one in Paris.

Thanks to him, parts of Paris have seen the sky for the first time since the city was a swamp. Twenty per cent of the city now consists of roads and open spaces; thirty per cent if one includes the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. For every square metre of land there are six square metres of floor space. The outer suburbs have been incorporated into the city, which is now fifty per cent larger than it was before 1860.

Recently, he has been asked to redesign Rome. The irony is not lost on him, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the son of Alsatian Protestants. The Archbishop of Paris paid him a compliment that is engraved in his memory and that he would like to see engraved on a plinth:

Your mission supports mine. In broad, straight streets that are bathed in light, people do not behave in the same slovenly fashion as in streets that are narrow, twisted and dark. To bring air, light and water to the pauper’s hovel not only restores physical health, it promotes good housekeeping and cleanliness, and thus improves morality.

It also allows a busy man like Baron Haussmann to reach any part of Paris within the hour and in a presentable condition. It means that he can dovetail his duties as a father and a husband with official functions, and with the performances of Mlle Cellier at the Opéra – the actress he dresses like his daughter – and Marie-Roze at the Opéra-Comique. He has created a city for lovers who also have families and jobs.

He was brought in as a steam-roller, as a man of experience and grit. He knows that a regime founders, not on barricades, but on committee tables. The Emperor would rather not disband the Conseil Municipal, but he would like to see it behave with one mind (his own). Baron Haussmann has no intention of running budgets like a petit bourgeois. The days of cautious, paternalistic Préfets are over. A great city like Paris must be allowed her whims and extravagance. Paris is a courtesan who demands a tribute of millions and a fully coordinated residence: flower-beds, kiosks, litter-bins, advertising columns, street furniture, chalets de nécessité. She will not be satisfied with small-scale improvements.

Later that month, his childhood home will be demolished.

He is often asked (though not as often as he would like) how he manages to run the city and to rebuild it at the same time. He tells them what he told his accountants and his engineers when he took over as Préfet de la Seine, thirteen years ago:

There is more time than most people think in twenty-four hours. Many things can be fitted in between six in the morning and midnight when one has an active body, an alert and open mind, an excellent memory, and especially when one needs only a modicum of sleep. Remember, too, that there are also Sundays, of which a year contains fifty-two.

Since he grasped the reins of power in 1853, three Heads of Accounting have died of exhaustion.

He looks down at the square and sees a row of taxi-cabs and a small detachment of cavalry. The Emperor is due to arrive, to view the commissioned photographs. His carriage will encounter a stretch of unrepaired tarmacadam where the Avenue Victoria meets the Rue Saint-Martin, and he will arrive approximately three minutes late.

Seventeen years ago, Louis-Napoléon arrived at the Gare du Nord with a map of Paris in his pocket, on which non-existent avenues were marked in blue, red, yellow and green pencil, according to the degree of urgency. Nearly all of those avenues have now been built or scheduled, and many of the Baron’s own ideas have enhanced the original plan. The Île de la Cité, where twenty thousand people lived like rats, is now an island of administrative buildings with the Morgue at its tip. The waters of the River Dhuys have been brought sixty miles by aqueduct, and Parisians are no longer forced to drink their own filth, pumped from the Seine or filtered through the corpses of their ancestors.

Haussmann told the Emperor about the conversation that took place after the council meeting – because the Emperor likes to hear about his steam-roller getting the better of ministers and civil servants:

‘You should have been a duke by now, Haussmann.’

‘Duke of what?’

‘Oh, I don’t know, Duc de la Dhuys.’

‘In that case, duc would not suffice.’

‘Is that so? What should it be, then? Prince?…’

‘No, I should have to be made an aqueduc, and that title is not to be found in the list of nobiliary titles!’

Some people say that the Emperor never laughs, but he laughed when he heard about the aqueduke.

Anything that binds him to the Emperor is good for Paris. That year, his daughter gave birth to the Emperor’s child, three days before her marriage, to which the Emperor gave his blessing. His Majesty even offered to pay for a dowry, which the Baron refused, because no one must be able to accuse him of corruption.

HE STANDS WHERE the mirror shows him in his entirety, from bald head to polished boot. At times like this, when a few extra minutes have been built into the schedule, he allows himself the luxury of remembering. He remembers the boy with the body of a man and an incongruous susceptibility to asthma. He remembers – in this order – his home in the quiet Quartier Beaujon, the boots that stood waiting for him every morning, the walk to lectures in the Latin Quarter, the depressing view that faced him like an insult from the arch of the old Pont Saint-Michel, and the state of his boots after the square where the drains of the Latin Quarter had their muddy confluence.

All that ugliness will vanish from one edition of the map to the next. The Boulevard Saint-Michel has smashed through the warren of streets, and the new Boulevard Saint-André will erase the Place Saint-André-des-Arts. The ends of the buildings exposed by the Boulevard Saint-Michel have been cauterized with a fountain on which a snarling Satan (too small for the Baron’s liking) is trampled by a Saint Michael with wings as beautiful as a waterproof cloak. He calls this his revenge on the past.

When he took the Emperor to see this new gateway to the Latin Quarter, the Emperor looked along the parallel lines of house-fronts, and his eye fell, as planned, on the spire of the Sainte-Chapelle across the river. Then he turned to the Baron and said, with a smile, ‘Now I can see why you were so keen on your symmetrical arrangement. You did it for the view!’

He hears the clatter of horses and guardsmen’s sabres on the square below. The Emperor will see the photographs and perhaps, this time, won’t tease him about his ‘weakness’ for symmetry. He always talks about London, where traffic and troop movements were the essential point. But, as Haussmann reminds him, ‘Parisians are more demanding than Londoners.’ He has been known to triple the width of an avenue for effect, and also, he would admit, to sabotage the paltry designs of the Emperor’s favourite architect, Hittorff. He may be a steam-roller but he understands the principles of beauty. A painting must always have a focal point and a frame, which is why it is now possible to stand in the middle of the Boulevard de Sébastopol and to see the Gare de l’Est at one end and the dome of the Tribunal de Commerce like a full stop at the other – except when the mists are rising from the Seine, filling the avenues and blurring perspectives, turning carriages and pedestrians into a procession of grey ghosts.

THE DOUBLE DOORS are opened to admit His Imperial Majesty Napoleon III.

The man still has the dimensions of the prison cell about him. He lives in palaces but looks as though he could fit into a tiny space at a moment’s notice. There is something about his smallness that commands respect. Baron Haussmann will not be asked to die for his Emperor, but he is prepared to sacrifice his reputation, which is besmirched almost every day – by liberals and socialists, who forget that the poor now have more hospital beds and proper graves; by nostalgic bohemians, who forget everything; and even by his own social equals, who find the inconvenience of moving house too heavy a price to pay for the most beautiful city in the world.

The framed photographs have been arrayed on the table in geographical order.

This makes a nice change from the usual squabbles with architects. (The Emperor speaks in short sentences, like an oracle.) He has sat for many photographers, but this Marville is unknown to him.

The Baron explains – it is unclear whether it was his idea or the Historical Committee’s: Marville is the official photographer of the Louvre. He takes photographs of emperors and pharaohs, Etruscan vases, and medieval cathedrals that are being demolished and rebuilt; he records artefacts that have been disinterred and rescued from the past. Marville was commissioned to photograph the sections of Paris that are about to be buried and forgotten. It might be seen as archaeology in reverse: first the ruins, then the city that covers them up. A copy of the Plan was given to M. Marville, who then set off to erect his tripod at every designated site.

At this, the Emperor turns his head towards the Baron with what could be a quizzical smile: knowledge of the Plan (as their enemies point out) would allow a speculator to buy up properties before the City expropriates them and pays a handsome compensation. But Marville is an artist, not a businessman – so much is clear from the photographs.

They stand at the table and survey the scenes that are about to disappear. They see the wasted space, the lack of uniformity, the corners where rubbish collects and thieves lurk. They sense the provincial hush and the age-old habits. Sometimes, there are flecks that might be bullet-holes in the walls, and scratches on the plate that look like scraps of cloud above a battlefield, but mostly the images are sharp and clean.

They pause over one print in particular, though it has nothing of obvious interest. It shows the back end of a square that looks overpopulated and deserted at the same time. The Baron identifies the tenements on the right as the handiwork of one of his predecessors, Prefect Rambuteau, and makes a rumbling sound of satisfied disapproval. He points to the tenements wedged into the corner of the square and the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts. The photographer has captured the anaemic radiance that fills the Latin Quarter in the early morning. The light that bathes the facade of no. 22 only intensifies the gloom. Its shielded windows suggest some secret life behind.

The building has wooden blinds instead of shutters, hung out over the window railings, which means that the day is warm but not windy. This is the economical style that was used by Prefect Rambuteau in the 1840s, with grooves scored in the plaster to imitate expensive freestone, and, instead of a continuous balcony, iron railings at the foot of each window and a ledge no wider than a kerb. Baron Haussmann remembers the scene from his student days: the area of no particular shape, veering off from the Place Saint-Michel; the bookshop at no. 22 with the puddle in front of it. The image is so vivid that, without thinking, he glances down at his boots.

Only a man who had walked there a thousand times would know that the neighbourhood is bulging with books. No. 22 alone contains one hundred thousand volumes, advertised as dépareillés, which means they belong to broken sets. This is a bookshop that can make a mystery of any life. It once shared the building with the publisher of ‘la Bibliothèque Populaire’, a series devoted to antiquities: Chardin’s history of the East Indies; Chanut’s Campagne de Bonaparte en Égypte et en Syrie. This is where Champollion-Figeac, brother of the decipherer of hieroglyphics, published his famous treatise on archaeology.

The quartier has barely changed. From one of those windows at no. 22, Baudelaire looked out on his first Parisian landscape. He was seven years old. His father was dead, and his mother was still in mourning. He wrote to his mother in 1861 and reminded her of their time together in the Place Saint-André-des-Arts: ‘Long walks and never-ending kindness! I remember the banks of the Seine that were so melancholy in the evening. For me, those were the good old days…I had you all to myself.’

By chance, no. 22 appears on another of the photographs, further along the table, at the foot of an advertisement for kitchen stoves and garden furniture: ‘The Special Billposting and Sign Company is still at 22, Rue Saint-André-des-Arts.’ Some of those advertisements that upset the poet’s mind must have come from his childhood home at no. 22. Coincidences like this are unremarkable in a set of four hundred and twenty-five photographs. If Baron Haussmann notices any of those words on the walls on Paris, it is only because wall space is a source of revenue for the city, and because some of the words are the visible portents of his power: ‘VENTE DE MOBILIER’, ‘FERMETURE POUR CAUSE D’EXPROPRIATION’, ‘BUREAU DE DÉMOLITION’.

THEY SPEND much longer than they mean to, staring at the glassy image. The Emperor has no intention of inspecting all four hundred and twenty-five photographs, but he lingers over this one, as though trying to dissolve some difficult thought into the image. The Baron adjusts his position once or twice. He pictures the gaping space that will open up where the masonry blocks the view. He briefly imagines himself standing on the demolition site, recognizing the twisted metal remnant of that balcony in the centre of the picture – if such a cluttered mess can be said to have a centre. He imagines the Emperor’s compliment when he notices the columns of the Odéon Theatre neatly framed at the far end of the new Boulevard Saint-André.

As he wedges a finger under the photograph to turn to the next one, the Emperor raises his hand. Something has occurred to him…He sometimes asks odd questions, perhaps on principle or simply out of distraction, it is hard to tell. He wants to know where the people are. (Marville is not there in person to explain; he has sent a messenger with the photographs.) Why are those daylit streets so empty? Is the quartier already half-abandoned?

The answer is obvious. The streets are empty because anything that moves, disappears – the smoke from a pipe, a cart-wheel turning a corner, a bird fluttering down to the cobbles. All movement is lost in long exposures. But this is one of those false gems of historical wisdom (photography has made such rapid progress): the thought of a sitter forced to resist an itch, smile frozen, head clamped…

The first photographic image of a human being in the open air is the scarecrow figure of a man on Daguerre’s photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, taken from the roof of his studio in 1838. This lone pioneer in the photographic past seems to have stopped at the last tree before the corner of the Rue du Temple to have his shoes shined. Everyone else has vanished, along with all the traffic. But in 1838, the shortest exposure time for a daguerreotype was fifteen minutes. Unless the bootblack was unusually conscientious, rubbing and buffing until a faint image of his face appeared on the leather, the man must have been sent down by the photographer to stand still for as long as he could in the river of vanishing pedestrians, to give some human life to the scene.

In 1865, exposure times have been reduced to the blink of an eye. In 1850, Gustave Le Gray was photographing summer landscapes in forty seconds. In 1853, the Emperor’s photographer, Disdéri, removed and replaced the cotton pad in front of the lens as quickly as a conjurer waving his wand: ‘If I count to two, the print is over-exposed.’ He took razor-sharp pictures of children, horses, ducks and a peacock displaying its tail, though, for some reason, he could never make the Emperor’s eyes look focused. Twelve years later, some of Marville’s photographs show dogs going about their business, stuck to the pavement in perfect, four-legged focus.

The streets are empty because this is early morning. But even in the heart of Paris, despite Baron Haussmann’s thirty-two thousand gas lamps, the working day is still regulated by the sun. The horses are standing on their shadows, and the hour is later than it seems. There is still just one ‘business district’ – around the new Opéra, where only bank managers and courtesans have nested in the expensive new apartments financed by men with close ties to Baron Haussmann’s son-in-law. Everyone else comes in from leafy quartiers in the west. Most Parisians commute to work from round the corner, from one room of the apartment to the next, or from the entresol to the shop below.

Baron Haussmann’s secretaries could produce the statistic in an instant: every minute, on the biggest and busiest boulevards – Capucines, Italiens, Poissonnière, Saint-Denis – at the busiest times of day, fewer than seven vehicles go past in both directions. On the Rue de Rivoli and the Champs-Élysées, one vehicle passes every twenty seconds. Just behind the photographer’s right shoulder, on the new Pont Saint-Michel, only the blind, the deaf, the lame, the distracted and the dithering are in danger from the traffic. Baudelaire was already suffering from premature old age when he wrote ‘To a Passer-By’ in 1860:

The deafening street was roaring all around me…

The woman whose eye he catches is ‘agile’ and ‘fleeting’, ‘lifting and swaying the hem and scallop of her dress’. She is dressed in formal mourning but still able to cross the road with dignity.

A flash…then darkness!…Shall I never see you again Until eternity begins?

A century later, the passer-by and the poet might have had time to start a conversation while they waited for the lights to change. They might have sat down at the pavement café, or stood still in the rushing crowd. A photographer with a high-speed camera might have caught them kissing…

Baron Haussmann leaves the Emperor’s question unanswered. The Emperor is probably thinking of London – the last place where he deigned to notice the life of the streets, and where he acquired his irksome predilection for ‘squares’ and tarmacadam, which is expensive and difficult to maintain.

‘Give me another year,’ says the Baron, ‘and I’ll turn that square into Piccadilly Circus.’

The Emperor has to leave for Compiègne, where the Empress goes riding in a forest filled with signposts. Before he leaves, he mentions the stretch of unrepaired tarmacadam on the Avenue Victoria. The Baron takes the opportunity to mention asphalt coating, wood-block paving, granite and porphyry slabs. He is investigating a new adhesive paste and leather soles for horses…The Emperor, as ever, appreciates the Baron’s sense of humour. He looks forward to seeing the later photographs, when the streets have been cleansed of their festering tenements and exposed to the full light of day.

III

IN A CITY that changes almost from one blink of an eye to the next, urban planners and photographers must resign themselves to the knowledge that some of their time will be wasted and their efforts in vain.

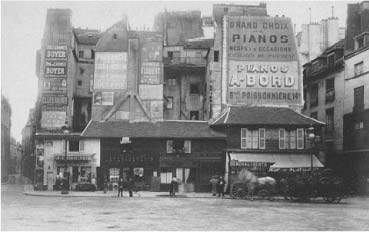

Under the soaring minarets of the Trocadéro Palace, which was constructed for the Universal Exhibition of 1878 by the architect who designed the fountain in the Place Saint-Michel, three rooms have been assigned to the City of Paris. One thousand wooden frames containing photographs are hinged to wooden columns and can be turned like the pages of a newspaper. The display is listed in the catalogue as ‘Modification of streets – photographs of streets old and new.’ The prints, which are so vivid that the viewer seems to be examining the scenes through a flawless lens, are paired with other photographs, of wide avenues, endless iron balconies and isolated monuments that retreat into the mist.

Charles Marville is not at the exhibition, and his name is not mentioned in the official report on the exhibits, which confines itself to generalities: ‘In the various branches of its immense administration, the City of Paris has continual recourse to photography.’ The report regrets the use of silver salts and gold-tone in the reproduction of prints ‘that will sooner or later disappear’, and it notes that the photographs have proved useful as forensic evidence ‘in questions of expropriation’.

The picture of the Place Saint-André-des-Arts is missing from the exhibition. Baron Haussmann is no longer at the Hôtel de Ville (he was forced to resign in 1870 to placate the liberal opposition), the Emperor has returned to exile in England and some of the avenues that were traced on the map in coloured pencil are in perpetual abeyance. The Boulevard Saint-André will never be completed. Marville himself has disappeared and his business has been sold. The last evidence of his activity is an invoice sent to the Committee of Historical Works for photographs of the new streets that replaced the old. A photographer with the name of his assistant died in 1878, and Marville is thought to have died at about the same time. The place of his death is unknown.

Though some of Marville’s techniques can be deduced from the surviving plates, his own opinions remain obscure. Nostalgia has coated his scenes with its tenacious patina, and in the absence of letters and reported conversations, no one knows what Marville himself thought about the modernization of Paris. His photographs might be portraits painted by a lover, or municipal documents in which the only trace of passion is the photographer’s love of light and shade and unsuspected detail.

THERE IS NOTHING to compare with the photograph of the Place Saint-André-des-Arts until 1898, when another photographer sets up his tripod on the same spot. He was once a cabin boy and then an actor. Now, Eugène Atget lugs his heavy bellows camera and his glass plates about the city, taking photographs which he sells to painters as ‘documents pour artistes’.

Thirty-three years have passed. The glassware depository has disappeared – demolished to make way for the street that never became a boulevard – but Mondet is still a big name in the quartier. The family came from the Hautes-Alpes, and its ‘Commerce de Vins’ now has a picturesque name: Café des Alpes. A removal cart and a dray loaded with barrels stand in front of the café, where a customer can eat the ‘Plat du jour’, screened from the square by the horse’s rump. The horse is at least two hands taller than the horses in Marville’s photograph. The invalid on his orthopedic bed has been replaced by an advertisement for a piano salesroom, two miles away across the river on the Boulevard Poissonnière. The balcony is still clinging to the masonry, with what appears to be the same railing, but the shed and its windows have gone. The light is murkier, either in reality or on the print, and there is no sign of the balcony’s inhabitant.

As time passes, it becomes harder to resolve the details. On a postcard that must have been printed in 1907, the scene is almost totally eclipsed by the black girders of a circular caisson being lowered into the square: this will be one of the entrances to the Saint-Michel Métro station. The wall above the café can be glimpsed through the girders: it carries an advertisement for the Dufayel chain of department stores, where everything can be bought for cash or on credit ‘at the same price in more than 700 shops in Paris and the provinces’. A postcard picture of the floods of January 1910, when the square lay under six inches of Seine water, is just sharp enough to show a new name on the café awning: ‘Au Rendez-Vous du Métro’.

In 1949, the little balcony makes a fleeting appearance in Burgess Meredith’s adaptation of a Simenon novel, The Man on the Eiffel Tower. Maigret’s sidekick pursues the mad villain (played by Franchot Tone), skipping impossibly across the chimneys all the way from Montmartre to the Place Saint-André-des-Arts. Tone drops down onto the balcony, opens the door and disappears.

In a book on Baudelaire’s Paris homes, published in 1967, a black-and-white photograph shows the café beneath the balcony (now called La Gentilhommière) half-obscured by a Citroën DS, but instantly recognizable from Marville’s photograph of a century before. It must have been taken at about the time when La Gentilhommière was frequented by Jack Kerouac, who came in search of ancestors, love and alcoholic illumination. The wall above the café is white and bare. Soon, it will be covered with graffiti, which appears in the early 1970s and changes faster than the advertisements ever did.

The balcony can still be seen on some images on the Internet: it seems to be one of those secret places that inspire a fleeting desire in anyone who happens to notice them. Some of the images show the building to the right of the café, on the corner of the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts. In the days of Baron Haussmann, when whole neighbourhoods were being reduced to rubble, and houses shook to the vibrations of demolition carts, no one would have guessed that Baudelaire’s childhood home would be standing after a century and a half. It still has blinds instead of shutters, perhaps because the windows of pre-Haussmann buildings are too close together to allow wooden shutters to be fully opened, or because buildings, like people, have ingrained habits, and there is little point in changing one’s ways when demolition is imminent.