Grip.

Grip.Marksmanship training is divided into two phases: preparatory marksmanship training and range firing. Each phase may be divided into separate instructional steps. All marksmanship training must be progressive. Combat marksmanship techniques should be practiced after the basics have been mastered.

The main use of the pistol is to engage an enemy at close range with quick, accurate fire. Accurate shooting results from knowing and correctly applying the elements of marksmanship. The elements of combat pistol marksmanship are:

Grip.

Grip.

Aiming.

Aiming.

Breath control.

Breath control.

Trigger squeeze.

Trigger squeeze.

Target engagement.

Target engagement.

Positions.

Positions.

A proper grip is one of the most important fundamentals of quick fire. The weapon must become an extension of the hand and arm; it should replace the finger in pointing at an object. The firer must apply a firm, uniform grip to the weapon.

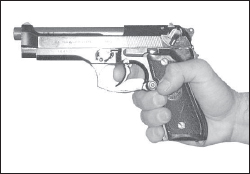

a. One-Hand Grip. Hold the weapon in the nonfiring hand; form a V with the thumb and forefinger of the strong hand (firing hand). Place the weapon in the V with the front and rear sights in line with the firing arm. Wrap the lower three fingers around the pistol grip, putting equal pressure with all three fingers to the rear. Allow the thumb of the firing hand to rest alongside the weapon without pressure (Figure 2-1). Grip the weapon tightly until the hand begins to tremble; relax until the trembling stops. At this point, the necessary pressure for a proper grip has been applied. Place the trigger finger on the trigger between the tip and second joint so that it can be squeezed to the rear. The trigger finger must work independently of the remaining fingers.

Figure 2-1. One-hand grip.

NOTE: If any of the three fingers on the grip are relaxed, the grip must be reapplied.

b. Two-Hand Grip. The two-hand grip allows the firer to steady the firing hand and provide maximum support during firing. The nonfiring hand becomes a support mechanism for the firing hand by wrapping the fingers of the nonfiring hand around the firing hand. Two-hand grips are recommended for all pistol firing.

WARNING

Do not place the nonfiring thumb in the rear of the weapon. The recoil upon firing could result in personal injury.

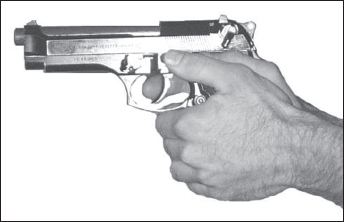

(1) Fist Grip. Grip the weapon as with the one-hand grip. Firmly close the fingers of the nonfiring hand over the fingers of the firing hand, ensuring that the index finger from the nonfiring hand is between the middle finger of the firing hand and the trigger guard. Place the nonfiring thumb alongside the firing thumb (Figure 2-2).

NOTE: Depending upon the individual firer, he may chose to place the index finger of his nonfiring hand on the front of the trigger guard since M9 and M11 pistols have a recurved trigger guard designed for this purpose.

Figure 2-2. Fist grip.

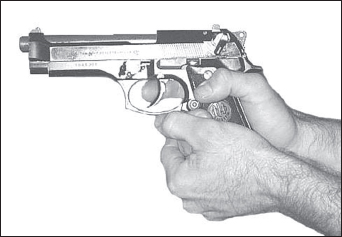

(2) Palm-Supported Grip. This grip is commonly called the cup and saucer grip. Grip the firing hand as with the one-hand grip. Place the nonfiring hand under the firing hand, wrapping the nonfiring fingers around the back of the firing hand. Place the nonfiring thumb over the middle finger of the firing hand (Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-3. Palm-supported grip.

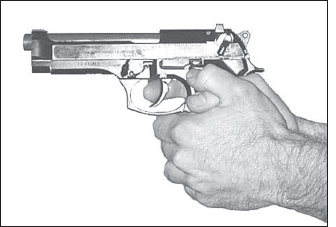

(3) Weaver Grip. Apply this grip the same as the fist grip. The only exception is that the nonfiring thumb is wrapped over the firing thumb (Figure 2-4).

Figure 2-4. Weaver grip.

c. Isometric Tension. The firer raises his arms to a firing position and applies isometric tension. This is commonly known as the push-pull method for maintaining weapon stability. Isometric tension is when the firer applies forward pressure with the firing hand and pulls rearward with the nonfiring hand with equal pressure. This creates an isometric force but never so much to cause the firer to tremble. This steadies the weapon and reduces barrel rise from recoil. The supporting arm is bent with the elbow pulled downward. The firing arm is fully extended with the elbow and wrist locked. The firer must experiment to find the right amount of isometric tension to apply.

NOTE: The firing hand should exert the same pressure as the nonfiring hand. If it does not, a missed target could result.

d. Natural Point of Aim. The firer should check his grip for use of his natural point of aim. He grips the weapon and sights properly on a distant target. While maintaining his grip and stance, he closes his eyes for three to five seconds. He then opens his eyes and checks for proper sight picture. If the point of aim is disturbed, the firer adjusts his stance to compensate. If the sight alignment is disturbed, the firer adjusts his grip to compensate by removing the weapon from his hand and reapplying the grip. The firer repeats this process until the sight alignment and sight placement remain almost the same when he opens his eyes. With sufficient practice, this enables the firer to determine and use his natural point of aim, which is the most relaxed position for holding and firing the weapon.

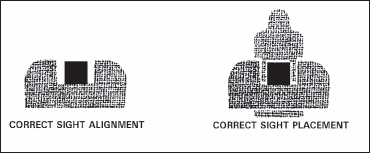

Aiming is sight alignment and sight placement (Figure 2-5).

a. Sight alignment is the centering of the front blade in the rear sight notch. The top of the front sight is level with the top of the rear sight and is in correct alignment with the eye. For correct sight alignment, the firer must center the front sight in the rear sight. He raises or lowers the top of the front sight so it is level with the top of the rear sight. Sight alignment is essential for accuracy because of the short sight radius of the pistol. For example, if a 1/10-inch error is made in aligning the front sight in the rear sight, the firer’s bullet will miss the point of aim by about 15 inches at a range of 25 meters. The 1/10-inch error in sight alignment magnifies as the range increases–at 25 meters, it is magnified 150 times.

b. Sight placement is the positioning of the weapon’s sights in relation to the target as seen by the firer when he aims the weapon (Figure 2-5). A correct sight picture consists of correct sight alignment with the front sight placed center mass of the target. The eye can focus on only one object at a time at different distances. Therefore, the last focus of the eye is always on the front sight. When the front sight is seen clearly, the rear sight and target will appear hazy. The firer can maintain correct sight alignment only through focusing on the front sight. His bullet will hit the target even if the sight picture is partly off center but still remains on the target. Therefore, sight alignment is more important than sight placement. Since it is impossible to hold the weapon completely still, the firer must apply trigger squeeze and maintain correct sight alignment while the weapon is moving in and around the center of the target. This natural movement of the weapon is referred to as wobble area. The firer must strive to control the limits of the wobble area through proper grip, breath control, trigger squeeze, and positioning.

Figure 2-5. Correct sight alignment and sight picture.

c. Focusing on the front sight while applying proper trigger squeeze will help the firer resist the urge to jerk the trigger and anticipate the moment the weapon will fire. Mastery of trigger squeeze and sight alignment requires practice. Trainers should use concurrent training stations or have fire ranges to enhance proficiency of marksmanship skills.

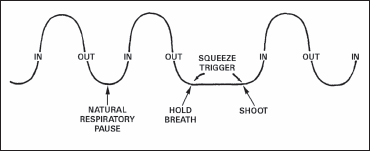

To attain accuracy, the firer must learn to hold his breath properly at any time during the breathing cycle. This must be done while aiming and squeezing the trigger. While the procedure is simple, it requires explanation, demonstration, and supervised practice. To hold his breath properly, the firer takes a breath, lets it out, then inhales normally, lets a little out until comfortable, holds, and then fires. It is difficult to maintain a steady position keeping the front sight at a precise aiming point while breathing. Therefore, the firer should be taught to inhale, then exhale normally, and hold his breath at the moment of the natural respiratory pause (Figure 2-6). (Breath control, firing at a single target.) The shot must then be fired before he feels any discomfort from not breathing. When multiple targets are presented, the firer must learn to hold his breath at any part of the breathing cycle (Figure 2-7). Breath control must be practiced during dry-fire exercises until it becomes a natural part of the firing process.

Figure 2-6. Breath control, target.

Figure 2-7. Breath control,

Improper trigger squeeze causes more misses than any other step of preparatory marksmanship. Poor shooting is caused by the aim being disturbed before the bullet leaves the barrel of the weapon. This is usually the result of the firer jerking the trigger or flinching. A slight off-center pressure of the trigger finger on the trigger can cause the weapon to move and disturb the firer’s sight alignment. Flinching is an automatic human reflex caused by anticipating the recoil of the weapon. Jerking is an effort to fire the weapon at the precise time the sights align with the target. For more on problems in target engagement, see paragraph 2-5.

a. Trigger squeeze is the independent movement of the trigger finger in applying increasing pressure on the trigger straight to the rear, without disturbing the sight alignment until the weapon fires. The trigger slack, or free play, is taken up first, and the squeeze is continued steadily until the hammer falls. If the trigger is squeezed properly, the firer will not know exactly when the hammer will fall; thus, he will not tend to flinch or heel, resulting in a bad shot. Novice firers must be trained to overcome the urge to anticipate recoil. Proper application of the fundamentals will lower this tendency.

b. To apply correct trigger squeeze, the trigger finger should contact the trigger between the tip of the finger and the second joint (without touching the weapon anywhere else). Where contact is made depends on the length of the firer’s trigger finger. If pressure from the trigger finger is applied to the right side of the trigger or weapon, the strike of the bullet will be to the left. This is due to the normal hinge action of the fingers. When the fingers on the right hand are closed, as in gripping, they hinge or pivot to the left, thereby applying pressure to the left (with left-handed firers, this action is to the right). The firer must not apply pressure left or right but should increase finger pressure straight to the rear. Only the trigger finger should perform this action. Dryfire training improves a firer’s ability to move the trigger finger straight to the rear without cramping or increasing pressure on the hand grip.

c. Follow-through is the continued effort of the firer to maintain sight alignment before, during, and after the round has fired. The firer must continue the rearward movement of the finger even after the round has been fired. Releasing the trigger too soon after the round has been fired results in an uncontrolled shot, causing a missed target.

(1) The firer who is a good shot holds the sights of the weapon as nearly on the target center as possible and continues to squeeze the trigger with increasing pressure until the weapon fires.

(2) The soldier who is a bad shot tries to “catch his target” as his sight alignment moves past the target and fires the weapon at that instant. This is called ambushing, which causes trigger jerk.

NOTE: The trigger squeeze of the pistol, when fired in the single-action mode, is 5.50 pounds; when fired in double-action mode, it is 12.33 pounds. The firer must be aware of the mode in which he is firing. He must also practice squeezing the trigger in each mode to develop expertise in both single-action and double- action target engagements.

To engage a single target, the firer applies the method discussed in paragraph 2-4. When engaging multiple targets in combat, he engages the closest and most dangerous multiple target first and fires at it with two rounds. This is called controlled pairs. The firer then traverses and acquires the next target, aligns the sights in the center of mass, focuses on the front sight, applies trigger squeeze, and fires. He ensures his firing arm elbow and wrist are locked during all engagements. If he has missed the first target and has fired upon the second target, he shifts back to the first and engages it. Some problems in target engagement are as follows:

a. Recoil Anticipation. When a soldier first learns to shoot, he may begin to anticipate recoil. This reaction may cause him to tighten his muscles during or just before the hammer falls. He may fight the recoil by pushing the weapon downward in anticipating or reacting to its firing. In either case, the rounds will not hit the point of aim. A good method to show the firer that he is anticipating the recoil is the ball-and-dummy method (see paragraph 2-14).

b. Trigger Jerk. Trigger jerk occurs when the soldier sees that he has acquired a good sight picture at center mass and “snaps” off a round before the good sight picture is lost. This may become a problem, especially when the soldier is learning to use a flash sight picture (see paragraph 2-7b).

c. Heeling. Heeling is caused by a firer tightening the large muscle in the heel of the hand to keep from jerking the trigger. A firer who has had problems with jerking the trigger tries to correct the fault by tightening the bottom of the hand, which results in a heeled shot. Heeling causes the strike of the bullet to hit high on the firing hand side of the target. The firer can correct shooting errors by knowing and applying correct trigger squeeze.

The qualification course is fired from a standing, kneeling, or crouch position. During qualification and combat firing, soldiers must practice all of the firing positions described below so they become natural movements. Though these positions seem natural, practice sessions must be conducted to ensure the habitual attainment of correct firing positions. Practice in assuming correct firing positions ensures that soldiers can quickly assume these positions without a conscious effort. Pistol marksmanship requires a soldier to rapidly apply all the fundamentals at dangerously close targets while under stress. Assuming a proper position to allow for a steady aim is critical to survival.

NOTE: During combat, there may not be time for a soldier to assume a position that will allow him to establish his natural point of aim. Firing from a covered position may require the soldier to adapt his shooting stance to available cover.

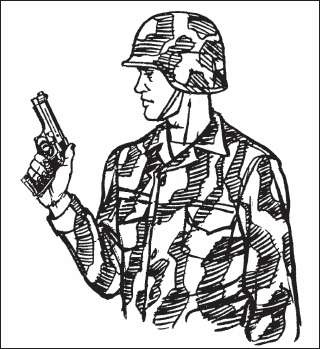

a. Pistol-Ready Position. In the pistol-ready position, hold the weapon in the one-hand grip. Hold the upper arm close to the body and the forearm at about a 45-degree angle. Point the weapon toward target center as you move forward (Figure 2-8).

Figure 2-8. Pistol-ready position.

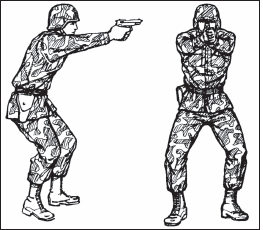

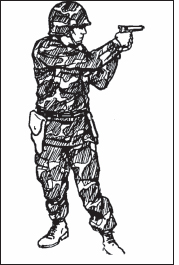

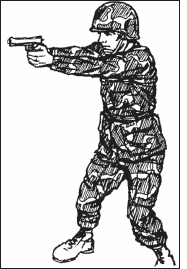

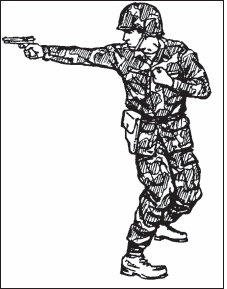

b. Standing Position without Support. Face the target (Figure 2-9). Place feet a comfortable distance apart, about shoulder width. Extend the firing arm and attain a two-hand grip. The wrist and elbow of the firing arm are locked and pointed toward target center. Keep the body straight with the shoulders slightly forward of the buttocks.

Figure 2-9. Standing position without support.

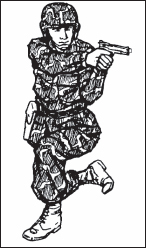

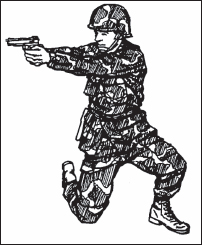

c. Kneeling Position. In the kneeling position, ground only your firing-side knee as the main support (Figure 2-10). Vertically place your firing-side foot, used as the main support, under your buttocks. Rest your body weight on the heel and toes. Rest your nonfiring arm just above the elbow on the knee not used as the main body support. Use the two-handed grip for firing. Extend the firing arm, and lock the firing-arm elbow and wrist to ensure solid arm control.

Figure 2-10. Kneeling position.

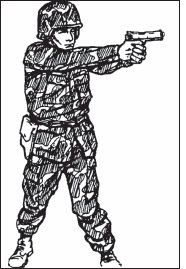

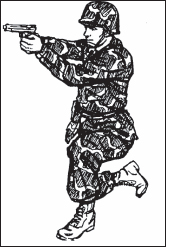

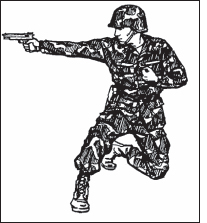

d. Crouch Position. Use the crouch position when surprise targets are engaged at close range (Figure 2-11). Place the body in a forward crouch (boxer’s stance) with the knees bent slightly and trunk bent forward from the hips to give faster recovery from recoil. Place the feet naturally in a position that allows another step toward the target. Extend the weapon straight toward the target, and lock the wrist and elbow of the firing arm. It is important to consistently train with this position, since the body will automatically crouch under conditions of stress such as combat. It is also a faster position from which to change direction of fire.

Figure 2-11. Crouch position.

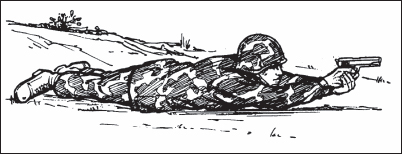

e. Prone Position. Lie flat on the ground, facing the target (Figure 2-12). Extend your arms in front with the firing arm locked. (Your arms may have to be slightly unlocked for firing at high targets.) Rest the butt of the weapon on the ground for single, well-aimed shots. Wrap the fingers of the nonfiring hand around the fingers of the firing hand. Face forward. Keep your head down between your arms and behind the weapon as much as possible.

Figure 2-12. Prone position.

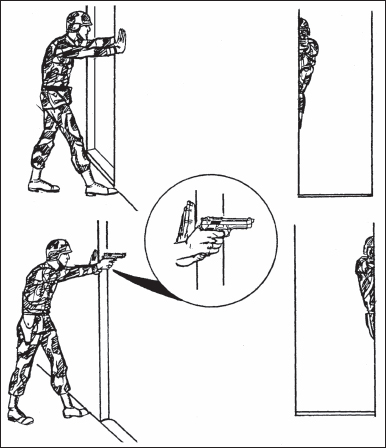

f. Standing Position with Support. Use available cover for support–for example, a tree or wall to stand behind (Figure 2-13). Stand behind a barricade with the firing side on line with the edge of the barricade. Place the knuckles of the nonfiring fist at eye level against the edge of the barricade. Lock the elbow and wrist of the firing arm. Move the foot on the nonfiring side forward until the toe of the boot touches the bottom of the barricade.

Figure 2-13. Standing position with support.

g. Kneeling Supported Position. Use available cover for support–for example, use a low wall, rocks, or vehicle (Figure 2-14). Place your firing-side knee on the ground. Bend the other knee and place the foot (nonfiring side) flat on the ground, pointing toward the target. Extend arms alongside and brace them against available cover. Lock the wrist and elbow of your firing arm. Place the nonfiring hand around the fist to support the firing arm. Rest the nonfiring arm just above the elbow on the nonfiring-side knee.

Figure 2-14. Kneeling supported.

After a soldier becomes proficient in the fundamentals of marksmanship, he progresses to advanced techniques of combat marksmanship. The main use of the pistol is to engage the enemy at close range with quick, accurate fire. In shooting encounters, it is not the first round fired that wins the engagement, but the first accurately fired round. The soldier should use his sights when engaging the enemy unless this would place the weapon within arm’s reach of the enemy.

Firing techniques include the use of hand-and-eye coordination, flash sight picture, quick-fire point shooting, and quick-fire sighting.

a. Hand-and-Eye Coordination. Hand-and-eye coordination is not a natural, instinctive ability for all soldiers. It is usually a learned skill obtained by practicing the use of a flash sight picture (see paragraph b below). The more a soldier practices raising the weapon to eye level and obtaining a flash sight picture, the more natural the relationship between soldier, sights, and target becomes. Eventually, proficiency elevates to a point so that the soldier can accurately engage targets in the dark. Each soldier must be aware of this trait and learn how to use it best. Poorly coordinated soldiers can achieve proficiency through close supervision from their trainers. Everyone has the ability to point at an object. Since pointing the forefinger at an object and extending the weapon toward a target are much the same, the combination of the two are natural. Making the soldier aware of this ability and teaching him how to apply it results in success when engaging enemy targets in combat.

(1) The eyes focus instinctively on the center of any object observed. After the object is sighted, the firer aligns his sights on the center of mass, focuses on the front sight, and applies proper trigger squeeze. Most crippling or killing hits result from maintaining the focus on the center of mass. The eyes must remain fixed on some part of the target throughout firing.

(2) When a soldier points, he instinctively points at the feature on the object on which his eyes are focused. An impulse from the brain causes the arm and hand to stop when the finger reaches the proper position. When the eyes are shifted to a new object or feature, the finger, hand, and arm also shift to this point. It is this inherent trait that can be used by the soldier to engage targets rapidly and accurately. This instinct is called hand-and-eye coordination.

b. Flash Sight Picture. Usually, when engaging an enemy at pistol range, the firer has little time to ensure a correct sight picture. The quick-kill (or natural point of aim) method does not always ensure a first-round hit. A compromise between a correct sight picture and the quick-kill method is known as a flash sight picture. As the soldier raises the weapon to eye level, his point of focus switches from the enemy to the front sight, ensuring that the front and rear sights are in proper alignment left and right, but not necessarily up and down. Pressure is applied to the trigger as the front sight is being acquired, and the hammer falls as the flash sight picture is confirmed. Initially, this method should be practiced slowly, with speed gained as proficiency increases.

c. Quick-Fire Point Shooting. This is for engaging an enemy at less than 5 yards and is also useful for night firing. Using a two-hand grip, the firer brings the weapon up close to the body until it reaches chin level. He then thrusts it forward until both arms are straight. The arms and body form a triangle, which can be aimed as a unit. In thrusting the weapon forward, the firer can imagine that there is a box between him and the enemy, and he is thrusting the weapon into the box. The trigger is smoothly squeezed to the rear as the elbows straighten.

d. Quick-Fire Sighting. This technique is for engaging an enemy at 5 to 10 yards away and only when there is no time available to get a full picture. The firing position is the same as for quick-fire point shooting. The sights are aligned left and right to save time, but not up and down. The firer must determine in practice what the sight picture will look like and where the front sight must be aimed to hit the enemy in the chest.

In close combat, there is seldom time to precisely apply all of the fundamentals of marksmanship. When a soldier fires a round at the enemy, he often does not know if he hits his target. Therefore, two rounds should be fired at the target. This is called controlled pairs. If the enemy continues to attack, two more shots should be placed in the pelvic area to break the body’s support structure, causing the enemy to fall.

In close combat, the enemy may be attacking from all sides. The soldier may not have time to constantly change his position to adapt to new situations. The purpose of the crouching or kneeling 360-degree traverse is to fire in any direction without moving the feet.

a. Crouching 360-Degree Traverse. The following instructions are for a right-handed firer. The two-hand grip is used at all times except for over the right shoulder. The firer remains in the crouch position with feet almost parallel to each other. Turning will be natural on the balls of the feet.

(1) Over the Left Shoulder (Figure 2-15): The upper body is turned to the left, the weapon points to the left rear with the elbows of both arms bent. The left elbow is naturally bent more than the right elbow.

(2) Traversing to the Left (Figure 2-16): The upper body turns to the right, and the right firing arm straightens out. The left arm is slightly bent.

(3) Traversing to the Front (Figure 2-17): The upper body turns to the front as the left arm straightens out. Both arms are straight forward.

(4) Traversing to the Right (Figure 2-18): The upper body turns to the right as both elbows bend. The right elbow is naturally bent more than the left.

Figure 2-15. Traversing over the left shoulder.

Figure 2-16. Traversing to the left.

Figure 2-17. Traversing to the front.

Figure 2-18. Traversing to the right.

(5) Traversing to the Right Rear (Figure 2-19): The upper body continues to turn to the right until it reaches a point where it cannot go further comfortably. Eventually the left hand must be released from the fist grip, and the firer will be shooting to the right rear with the right hand.

Figure 2-19. Traversing to the right rear.

b. Kneeling 360-Degree Traverse. The following instructions are for right-handed firers. The hands are in a two-hand grip at all times. The unsupported kneeling position is used. The rear foot must be positioned to the left of the front foot.

(1) Traversing to the Left Side (Figure 2-20): The upper body turns to a comfortable position toward the left. The weapon is aimed to the left. Both elbows are bent with the left elbow naturally bent more than the right elbow.

(2) Traversing to the Front (Figure 2-21): The upper body turns to the front, and a standard unsupported kneeling position is assumed. The right firing arm is straight, and the left elbow is slightly bent.

(3) Traversing to the Right Side (Figure 2-22): The upper body turns to the right as both arms straighten out.

(4) Traversing to the Rear (Figure 2-23): The upper body continues to turn to the right as the left knee is turned to the right and placed on the ground. The right knee is lifted off the ground and becomes the forward knee. The right arm is straight, while the left arm is bent. The direction of the kneeling position has been reversed.

Figure 2-20. Traversing to the left, kneeling.

Figure 2-21. Traversing to the front, kneeling.

Figure 2-22. Traversing to the right, kneeling.

Figure 2-23. Traversing to the rear, kneeling.

(5) Traversing to the New Right Side (Figure 2-24): The upper body continues to the right. Both elbows are straight until the body reaches a point where it cannot go further comfortably. Eventually, the left hand must be released from the fist grip, and the firer is shooting to the right with the one-hand grip.

Figure 2-24. Traversing to the new right side, kneeling.

c. Training Method. This method can be trained and practiced anywhere and, with the firer simulating a two-hand grip, without a weapon. The firer should be familiar with firing in all five directions.

Overlooked as a problem for many years, reloading has resulted in many casualties due to soldiers’ hands shaking or errors such as dropped magazines, magazines placed in the pistol backwards, or empty magazines placed back into the weapon. The stress state induced by a life-threatening situation causes soldiers to do things they would not otherwise do. Consistent, repeated training is needed to avoid such mistakes.

NOTE: These procedures should be used only in combat, not on firing ranges.

a. Develop a consistent method for carrying magazines in the ammunition pouches. All magazines should face down with the bullets facing forward and to the center of the body.

b. Know when to reload. When possible, count the number of rounds fired. However, it is possible to lose count in close combat. If this happens, there is a distinct difference in recoil of the pistol when the last round has been fired. Change magazines when two rounds may be left–one in the magazine and one in the chamber. This prevents being caught with an empty weapon at a crucial time. Reloading is faster with a round in the chamber since time is not needed to release the slide.

c. Obtain a firm grip on the magazine. This precludes the magazine being dropped or difficulty in getting the magazine into the weapon. Ensure the knuckles of the hand are toward the body while gripping as much of the magazine as possible. Place the index finger high on the front of the magazine when withdrawing from the pouch. Use the index finger to guide the magazine into the magazine well.

d. Know which reloading procedure to use for the tactical situation. There are three systems of reloading: rapid, tactical, and one-handed. Rapid reloading is used when the soldier’s life is in immediate danger and the reload must be accomplished quickly. Tactical reloading is used when there is more time and it is desirable to keep the replaced magazine because there are rounds still in it or it will be needed again. One-handed reloading is used when there is an arm injury.

(1) Rapid Reloading.

(a) Place your hand on the next magazine in the ammunition pouch to ensure there is another magazine.

(b) Withdraw the magazine from the pouch while releasing the other magazine from the weapon. Let the replaced magazine drop to the ground.

(c) Insert the replacement magazine, guiding it into the magazine well with the index finger.

(d) Release the slide, if necessary.

(e) Pick up the dropped magazine if time allows. Place it in your pocket, not back into the ammunition pouch where it may become mixed with full magazines.

(2) Tactical Reloading.

(a) Place your hand on the next magazine in the ammunition pouch to ensure there is a remaining magazine.

(b) Withdraw the magazine from the pouch.

(c) Drop the used magazine into the palm of the nonfiring hand, which is the same hand holding the replacement magazine.

(d) Insert the replacement magazine, guiding it into the magazine well with the index finger.

(e) Release the slide, if necessary.

(f) Place the used magazine into a pocket. Do not mix it with full magazines.

(3) One-Hand Reloading, Right Hand.

(a) Push the magazine release button with the thumb.

(b) Place the safety ON with the thumb if the slide is forward.

(c) Place the weapon backwards into the holster.

NOTE: If placing the weapon in the holster backwards is a problem, place the weapon between the calf and thigh to hold the weapon.

(d) Insert the replacement magazine.

(e) Withdraw the weapon from the holster.

(f) Remove the safety with the thumb if the slide is forward, or push the slide release if the slide is back.

(4) One-Hand Reloading, Left Hand.

(a) Push the magazine release button with the middle finger.

(b) Place the weapon backwards into the holster.

NOTE: If placing the weapon in the holster backwards is a problem, place the weapon between the calf and thigh to hold the weapon.

(c) Insert the replacement magazine.

(d) Remove the weapon from the holster.

(e) Remove the safety with the thumb if the slide is forward, or push the slide release lever with the middle finger if the slide is back.

Poor visibility firing with any weapon is difficult since shadows can be misleading to the firer. This is mainly true during EENT and EMNT (a half hour before dark and a half hour before dawn). Even though the pistol is a short-range weapon, the hours of darkness and poor visibility further decrease its effect. To compensate, the firer must use the three principles of night vision:

a. Dark Adaptation. This process conditions the eyes to see during poor visibility conditions. The eyes usually need about 30 minutes to become 90 percent adapted in a totally darkened area.

b. Off-Center Vision. When looking at an object in daylight, a person looks directly at it. However, at night he would see the object only for a few seconds. To see an object in darkness, he must concentrate on it while looking 6 to 10 degrees away from it.

c. Scanning. This is the short, abrupt, irregular movement of the firer’s eyes around an object or area every 4 to 10 seconds. With artificial illumination, the firer uses night-fire techniques to engage targets, since targets seem to shift without moving.

NOTE: For more detailed information on the three principles of night vision, see FM 21-75 (US Army Field Manual 21-75).

When firing a pistol under CBRN conditions, the firer should use optical inserts, if applicable. Firing in MOPP levels 1 through 3 should not be a problem for the firer. Unlike with a rifle, the firer acquires a sight picture with a pistol the same with or without a protective mask. MOPP4 is the only level that might present a problem for a firer, because that level requires him to wear gloves. Gloves could force him to adjust for proper grip and trigger squeeze. Firers should practice firing in MOPP4 to become proficient in CBRN firing.

Throughout preparatory marksmanship training, the coach-and-pupil method of training should be used. The proficiency of a pupil depends on how well the coach performs his duties. This section provides detailed information on coaching techniques and training aids for pistol marksmanship.

The coach assists the firer by correcting errors, ensuring he takes proper firing positions, and ensuring he observes all safety precautions. The criteria for selecting coaches are a command responsibility. Coaches must have more experience in pistol marksmanship than the student firer. Duties of the coach during instructional practice and record fire include the following:

a. Checking that the:

Weapon is clear.

Weapon is clear.

Ammunition is clean.

Ammunition is clean.

Magazines are clean and operational.

Magazines are clean and operational.

b. Observing the firer to see that he:

Takes the correct firing position.

Takes the correct firing position.

Loads the weapon properly and only on command.

Loads the weapon properly and only on command.

Takes up the trigger slack correctly.

Takes up the trigger slack correctly.

Squeezes the trigger correctly.

Squeezes the trigger correctly.

Calls the shot each time he fires, except during quick fire and rapid fire.

Calls the shot each time he fires, except during quick fire and rapid fire.

Holds his breath correctly.

Holds his breath correctly.

When he does not fire for 5 or 6 seconds, lowers the weapon and rests his arm.

When he does not fire for 5 or 6 seconds, lowers the weapon and rests his arm.

c. Having the firer breathe deeply several times to relax if he is tense.

In this method, the coach loads the weapon for the firer. He may hand the firer a loaded weapon or an empty one. When firing the empty weapon, the firer observes that in anticipating recoil he is forcing the weapon downward as the hammer falls. Repetition of the ball-and-dummy method helps reduce recoil anticipation.

To call the shot is to state where the bullet should strike the target according to the sight picture at the instant the weapon fires, for example, “High,” “a little low,” “to the left,” or “bull’s eye.” Another method of calling the shot is the clock system, for example, “three-ring hit at 8 o’clock” or “four-ring hit at 5 o’clock.” Another method is to place a firing center beside the firer on the firing line. As soon as the shot is fired, the firer must place a finger on the target face or center where he expects the round to hit on the target. This method avoids guessing and computing for the firer. The immediate placing of the finger on the target face gives an accurate call. If the firer calls his shot incorrectly in range fire, he is failing to concentrate on sight alignment and trigger squeeze. Thus, as the weapon fires, he does not know what his sight picture is.

The slow-fire exercise is one of the most important exercises for both amateur and competitive marksmen. Coaches should ensure firers practice this exercise as much as possible. This is a dry-fire exercise.

a. To perform the slow-fire exercise, the firer assumes the standing position with the weapon pointed at the target. The firer should begin by using the two-hand grip, progressing to the one-hand grip as his skill increases. He takes in a normal breath and lets out part of it, locking the remainder in his lungs by closing his throat. He then relaxes, aims at the target, and takes the correct sight alignment and sight picture. He takes up the trigger slack and squeezes the trigger straight to the rear with steady, increasing pressure until the hammer falls, simulating firing.

b. If the firer does not cause the hammer to fall in 5 or 6 seconds, he should return to the pistol-ready position and rest his arm and hand. He then starts the procedure again. The action sequence that makes up this process can be summed up by the key word BRASS. It is a word the firer should think of each time he fires his weapon.

| Breathe | Take a normal breath, let part of it out, and lock the remainder in the lungs by closing the throat. |

| Relax | Relax the body muscles. |

| Aim | Take correct sight alignment and sight picture, and focus the eye at the top of the front sight. |

| Slack | Take up the trigger slack. |

| Squeeze | Squeeze the trigger straight to the rear with steadily increasing pressure without disturbing sight alignment until the hammer falls. |

c. Coaches should observe the front sight for erratic movements during the application of trigger squeeze. Proper application of trigger squeeze allows the hammer to fall without the front sight moving. A small bouncing movement of the front sight is acceptable. Firers should call the shot by the direction of movement of the front sight (high, low, left, or right).

The air-operated pistol is used as a training device to teach the soldier the method of quick fire, to increase confidence in his ability, and to afford him more practice firing. A range can be set up almost anywhere with a minimum of effort and coordination, which is ideal for USAR and NG. If conducted on a standard range, live firing of pistols can be conducted along with the firing of the .177-mm air-operated pistol. Due to light recoil and little noise of the pistol, the soldier can concentrate on fundamentals. This helps build confidence because the soldier can hit a target faster and more accurately. The air-operated pistol should receive the same respect as any firearm. A thorough explanation of the weapon and a safety briefing are given to each soldier.

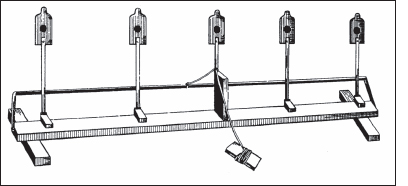

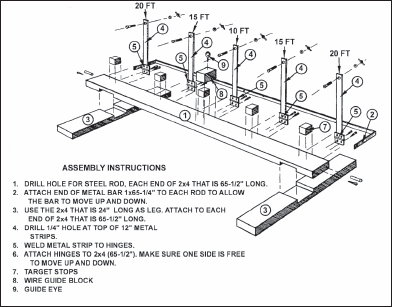

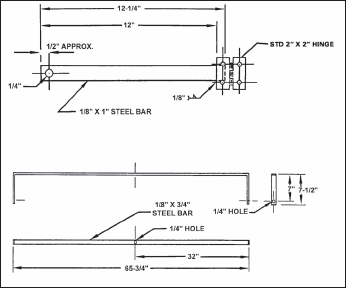

The QTTD (Figures 2-25 and 2-26) is used with the .177-mm air-operated pistol.

Figure 2-25. The quick-fire target training device.

a. Phase I. From 10 feet, five shots at a 20-foot miniature E-type silhouette. After firing each shot, the firer and coach discuss the results and make corrections.

b. Phase II. From 15 feet, five shots at a 20-foot miniature E-type silhouette. The same instructions apply to this exercise as for Phase I.

c. Phase III. From 20 feet, five shots at a 20-foot miniature E-type silhouette. The same instructions apply to this exercise as for Phases I and II.

Figure 2-26. Dimensions for the QTTD.

d. Phase IV. From 15 feet, six shots at two 20-foot miniature E-type silhouettes. This exercise is conducted the same as the previous one, except that the firer is introduced to fire distribution. The targets on the QTTD are held in the up position so they cannot be knocked down when hit.

(1) The firer first engages the 20-foot miniature E-type silhouette on the extreme right of the QTTD (see Figure 2-27). He then traverses between targets and engages the same type target on the extreme left of the QTTD. The firer again shifts back to reengage the first target. The procedure is used to teach the firer to instinctively return to the first target if he misses it with his first shot.

(2) The firer performs this exercise twice, firing three shots each time. Before firing the second time, the coach and firer should discuss the errors made during the first exercise.

Figure 2-27. Miniature E-type silhouette for use with QTTD.

e. Phase V. Seven shots fired from 20, 15, and 10 feet at miniature E-type silhouettes.

(1) The firer starts this exercise 30 feet from the QTTD. The command MOVE OUT is given, and the firer steps out at a normal pace with the weapon held in the ready position. Upon the command FIRE (given at the 20-foot line), the firer assumes the crouch position and engages the 20-foot miniature E-type silhouette on the extreme right of the QTTD. He then traverses between targets, engages the same type target on the extreme left of the QTTD, and shifts back to the first target. If the target is still up, he engages it. The firer then assumes the standing position and returns the weapon to the ready position. (Upon completion of each exercise, the coach makes corrections as the firer returns to the standing position.)

Figure 2-27. Miniature E-type silhouette for use with QTTD (continued).

Figure 2-27. Miniature E-type silhouette for use with QTTD (continued).

(2) On the command MOVE OUT, the firer again steps off at a normal pace. Upon the command FIRE (given at the 15-foot line), he engages the 15-foot targets on the QTTD. The same sequence of fire distribution is followed as with the previous exercise.

(3) During this exercise, the firer moves forward on command until he reaches the 10-foot line. At the command FIRE, the firer engages the 10-foot miniature E-type silhouette in the center of the QTTD.

Range firing is conducted after the firers have satisfactorily completed preparatory marksmanship training. The range firing courses are:

a. Instructional. Instructional firing is practice firing on a range, using the assistance of a coach.

(1) All personnel authorized or required to fire the pistol receive 12 hours of preliminary instruction that includes the following:

Disassembly and assembly.

Disassembly and assembly.

Loading, firing, unloading, and immediate action.

Loading, firing, unloading, and immediate action.

Preparatory marksmanship.

Preparatory marksmanship.

Care and cleaning.

Care and cleaning.

(2) The tables fired for instructional practice are prescribed in the combat pistol qualification course in Appendix A. During the instructional firing, the CPQC is fired with a coach or instructor.

b. Combat Pistol Qualification. The CPQC stresses the fundamentals of quick fire. It is the final test of a soldier’s proficiency and the basis for his marksmanship classification. After the soldier completes the instructional practice firing, he shoots the CPQC for record. Appendix A provides a detailed description of the CPQC tables, standards, and conduct of fire. TC 25-8 provides a picture of the course.

NOTE: The alternate pistol qualification course (APQC) can be used for sustainment/qualification if the CPQC is not available (see Appendix B).

c. Military Police Firearms Qualification. The military police firearms qualification course is a practical course of instruction for police firearms training (see FM 19-10).

Safety must be observed during all marksmanship training. Listed below are the precautions for each phase of training. It is not intended to replace AR 385-63 or local range regulations. Range safety requirements vary according to the requirements of the course of fire. It is mandatory that the latest range safety directives and local range regulations be consulted to determine current safety requirements.

The following requirements apply to all marksmanship training.

a. Display a red flag prominently on the range during all firing.

b. Soldiers must handle weapons carefully and never point them at anyone except the enemy in actual combat.

c. Always assume a weapon is loaded until it has been thoroughly examined and found to contain no ammunition.

d. Indicate firing limits with red and white striped poles visible to all firers.

e. Never place obstructions in the muzzle of any weapon about to be fired.

f. Keep weapons in a prescribed area with proper safeguards.

g. Refrain from smoking on the range near ammunition, explosives, or flammables.

The following requirements must be met before conducting marksmanship training.

a. Close and post guards at all prescribed roadblocks and barriers.

b. Ensure all weapons are clear of ammunition and obstructions, and all slides are locked to the rear.

c. Brief all firers on the firing limits of the range and firing lanes. Firers must keep their fires within prescribed limits.

d. Ensure all firers receive instructions on know how to load and unload the weapon and on safety features.

e. Brief all personnel on all safety aspects of fire and of the range pertaining to the conduct of the courses.

f. No one moves forward of the firing line without permission of the tower operator, safety officer, or OIC.

g. Weapons are loaded and unlocked only on command from the tower operator except during conduct of the courses requiring automatic magazine changes.

h. Weapons are not handled except on command from the tower operator.

i. Firers must keep their weapons pointed downrange when loading, preparing to fire, or firing.

The following requirements apply during marksmanship training.

a. A firer does not move from his position until his weapon has been cleared by safety personnel and placed in its proper safety position. An exception is the assault phase.

b. During Table 5 of the CPQC, firers remain on line with other firers on their right or left.

c. Firers must fire only in their own firing lane and must not point the weapon into an adjacent lane, mainly during the assault phase.

d. Firers treat the air-operated pistol as a loaded weapon, observing the same safety precautions as with other weapons.

e. All personnel wear helmets during live-fire exercises.

f. Firers hold the weapon in the raised position except when preparing to fire. They then hold weapons in the ready position, pointed downrange.

Safety personnel inspect all weapons to ensure they are clear. A check is conducted to determine if any brass or live ammunition is in the possession of the soldiers. Once cleared, pistols are secured with the slides locked to the rear.

During these phases of firing, safety personnel ensure that:

a. The firer understands the conduct of the exercise.

b. The firer has the required ammunition and understands the commands for loading and unloading.

c. The firer complies with all commands from the tower operator.

d. Firers maintain proper alignment with other firers while moving downrange.

e. Weapons are always pointed downrange.

f. Firers fire within the prescribed range limits.

g. Weapons are cleared after each phase of firing, and the tower-operator is aware of the clearance.

h. Malfunctions or failures to fire that are due to no fault of the firer are reported immediately. On command of the tower operator, the weapon is cleared and action is taken to allow the firer to continue with the exercise.

NOTE: For training and qualification standards, see Appendixes A through D.