At one time I was a champ but now I’m wondering if I’ve become a chump? Or only a chimp with car keys? By the age of thirty, I had climbed all of the major mountain peaks of the Midwest. One of them, in particular, near Kingsley, Michigan, intrigued me and challenged me. Known locally only as “the Big Hill,” it was a very big hill indeed. There were no trails, no available mapped routes, and there was the sensation of climbing an enormous virgin, perhaps like the tiniest of ants might feel climbing the leg of a Sapphic giantess after she had bathed in a forest spring. I was also burdened by an onion sack of morels because it was mid-May in the Great North. On my descent, while sobbing with exhaustion and cold, I was met by a dense fog of mosquitoes but luckily caught a brown trout of about three pounds on the Manistee. I roasted the trout and sautéed the morels with wild leeks for my little family.

To be frank, we were fraught with worry. We lived in a shabby house rented for thirty-five bucks a month. It was a questionable deal because many nights in the winter the temperature couldn’t be raised to fifty and my little daughter wore her snowsuit to bed. My abs (abdominal muscles) rippled from manual labor at two dollars an hour. My head was swollen with the pride of having published my first book of poems with W. W. Norton. I refused to teach, thinking it unworthy of a Thief of Fire. In short, I was the same sort of flaming asshole that most young poets are with the inevitability of winter ice on Hudson Bay. At the time, a visiting rich friend said, ‘‘This is so Dickensian.”

Soon enough, however, my career wildly burgeoned with readings throughout our great nation for the National Endowment for the Arts for a hundred dollars a performance. The experience was so absolutely gruesome that over thirty-five years later, I claw at my face when thinking about it. In Detroit, I lost my plane tickets in a strip club. In Minneapolis, it was thirty below in January and I fell down a snowy bank of the Mississippi River. If it hadn’t been for a solid lid of ice, I would have perished. On an Indian reservation in Arizona, a huge girl lunged at me with her pet rattlesnake. She was thrilled to frighten me.

Oddly, this kind of thing is still happening, though at a slightly higher fee. When we jump ahead from then to now through the vast shitstorm clouds of public appearances, however, I feel obliged to help others. Along with murder and thieving it is the Christian thing to do. It’s always improper to whine, or so my mother said, but then she mostly traveled to the rural mailbox and the grocery store. How can I help other poets? Easy. By advising them to get a job and not to do readings. I remember the day in my mid-thirties when I received a letter announcing I had been chosen for the “Texas Tour,” which was nineteen readings in thirty days. While composing a “no” letter, I wondered idly what such activities had to do with the writing of poetry. There are many who think that all of the social activities surrounding literature are part of literature. They aren’t. Nothing matters but the work itself.

How did I liberate myself from this squalid world: the garrulity that is a central manifestation of mediocrities; the bus, train, and plane travel; the colleges that were green lumps of ivy on suburban hills; the ten thousand professors who, like realtors and editors, tell you that they don’t have time to read?

I did so by becoming, briefly, a chef in a women’s prison, and then an international white trash sports fop, and then the lowliest of functionaries in Hollywood, the “writer”—a word that is uttered with sardonic amusement out there, raising images of a nerd who drives an old Honda.

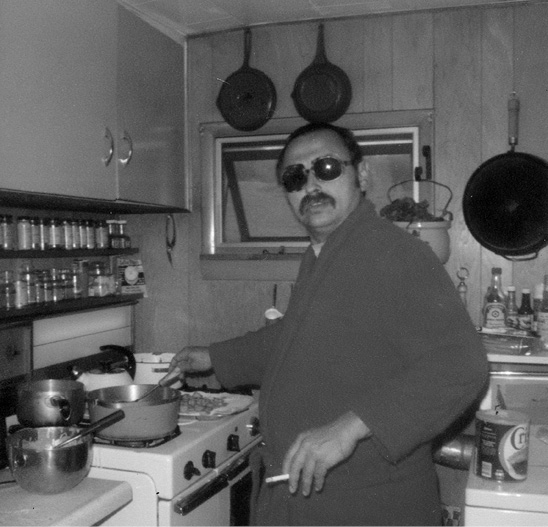

Cooking at a women’s prison—really a low-security home for wayward girls, though a number of prisoners were murderers—was hard work but not unpleasant. Before I began, my heart soared because I’ve always enjoyed cooking for crowds. Even as a child, I’d make hundreds of mud pies for friends. Unfortunately, state institutions had rigid guidelines for prisoner food, including heavy use of government surplus. I’ve never been one to be intimidated by government regulations, with the exception of several raids by the IRS on my person. The problem at the women’s prison was that the menus were preset by the state and there was no budget whatsoever for fresh garlic and red wine. Perhaps the prohibition against red wine is understandable for criminals, but then they always seem to be gobbling drugs with impunity and the availability of red wine would be a health measure. (Drug use in state and federal prisons runs consistently over 80 percent and it’s puzzling how governments expect to control drug use in the free world when they can’t do so in their prisons.)

Sad to say, my chef job lasted a scant month. My staff was a mélange of ethnic and racial backgrounds and uniformly ungifted as sous chefs. Sample dialogue:

“Girls, we need to peel two bushels of russet potatoes,” I’d say.

“Eat shit, white boy,” said Vera, a large black heroin dealer from the Cass Corridor of Detroit.

“Chinga su madre,” said Rosa, a heroin mule from Sonora.

And so it went.

I had to buy fresh garlic and herbs out of my own pocket until one day a half dozen of these monster vixens wrestled me into submission on a pile of dirty laundry. Big rumps broke my nose and loosened two teeth. When I cried out and we were discovered by a guard, I was judged the guilty party and fired. I do remember fondly certain of the malcontents—Carrie, Judy, Mara, Evelyn, Meredith—our late-night Crisco fights over the tubs of tuna with Judy sitting happily in the big bowl of mayo. Amid the squalor of newspapers, television news, bad jobs, bad government, it was exhilarating that there is a durable spiritual aspect of food and sex, that even in a prison kitchen, tuna and tarts can be a form of prayer.

I’ll hastily move through my career as an international white trash sports fop and a Hollywood shill. In the former, I was self-indulgent in Africa, Russia, and Central and South America in a single year. I caught fish and shot game birds and wrote about it, a somewhat limited genre. In Hollywood, I wrote brilliant screenplays that were turned into mediocre movies. I quit in disgust seven years ago and gave myself over totally to literature. Since quitting, I have done fourteen book tours in the United States and France, which are every bit as nasty as Hollywood pig poop. Publishing and Hollywood are busy cloning each other and contain the same mushy innards one discovers when cleaning squid. Naturally I love good books and good movies but they are as rare as honest Republicans.

Many people ask me, “Jim, how do you survive the mudbath you’ve organized as a life?” The answer is easy. Food and wine. Just this moment, in Grand Marais, Michigan, on the eve of a book tour to France, where I’ll be winning certain prizes that, like those I’ve won in America, I’ve never heard of, I’ve opened a Sangre de Toro, an ordinary Spanish red, with its secret ingredient, the blood of a bull. Of course bulls are rather unreliable as role models so I should have opened a Vacqueyras Sang des Cailloux (the blood of the rock), but this wine is unavailable in the Upper Peninsula. When the blood is thin, drink blood. Even faux blood will suffice. Our strength comes from metaphor not reality.

This key to vigorous survival was found in a mere ten minutes of reading in Chinese medicine. I admit that this scarcely represents mastery of the subject but who cares? The world is full of nitwit authorities. Chew a leaf a few minutes and you know the tree. Everyone should understand that the hardest thing is still melody which presumes harmony. The dimensions and the nature of the universe make all human pretensions and inventions not much more than silly. The DNA of a flea is more intricate than Mozart, though admittedly, I’d rather listen to Mozart than a dead flea.

Life must go on after my failed attempt to become an Olympic synchronized swimmer, and after that, to write an opera based on women’s TV exercise programs. The women frequently die after wrapping themselves into these Rube Goldberg machines, all to make themselves attractive to louts.

On a recent book tour that covered nineteen cities in thirty-five days, I used the Chinese one-on-one concept and it saved my heart and brain from exploding. When my stomach was sore I ate tripe in the form of menudo at Mexican restaurants. When my mouth was tired from babbling I ate Jewish corned tongue and guanciale, Italian treated pork cheeks. For sore feet it was pig hocks, and tired legs demanded beef shanks and lamb legs. When my gizzard was on the fritz I was lucky enough to find confit de gésiers at Vincent’s in Minneapolis. In the same city toward the end of my tour I acquired a Russian peasant heartiness by eating borscht and Russian sausage and drinking Russian wheat beer at Kramarczuk’s. My fatigued tendons recuperated by eating stewed tendons at the Family Noodle Shop in New York City. In Seattle, Armandino Batali cooked me a giant beef tail for general strength, and in New York City, his son Mario and I tested forty dishes at his restaurants to cover all the possibly neglected basics. One giant lacuna in America is finding a restaurant that serves both brains and testicles, though both are frequently served in Montana in the vicinity of my home.

Well, you see the drift. I admit I spent more money than usual on digestive nostrums. Now I’m on the eve of a French book tour where it will be easy to find brains and tongue, also skate wings au beurre noir, which will help me fly through the cultural sewer of book publication, the photo ops and endless babbling. I have been diverted by an item on television news that described a punishment fad among American parents called “hot saucing,” wherein they dab the tongues of their naughty children with hot sauce. I’ve always considered Tabasco a sacrament so this new practice strikes me as another gesture of the Antichrist, or at least the advent of torture into child raising.

This is my last day in the Great North. After preparing my simple Spanish chicken dinner dish I’m setting off for a long wilderness hike with the ghost of my dog Rose, who died this summer as a result of my inattention as I convalesced from my book tour. In one of the grand vagaries of the human mind and imagination, I can occasionally see Rose on my hikes. She crisscrosses the landscape, a white setter against the greenery, looking for ghost birds.