One Good Thing

Leads to Another

I am intensely knowledgeable on all matters nutritional but somewhat ineffective in applying this knowledge to myself. A friend, the novelist Tom McGuane, once said to me, “You can lecture a group of us on nutritional health while chain smoking and drinking a couple of bottles of wine in less than an hour.”

Sad but true, but how sad? Ben Franklin said, “Wine is constant proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.” Despite this many Americans own a hopeless puritanical streak that makes them beat on themselves as if they were building a tract house. The other day I took out a pound of side pork from the refrigerator, exemplary side pork raised by E.T. Poultry which I favor above all domestic pork. I put the package on the table and circled it nervously like a nun tempted to jump over the convent wall and indulge in the lusts of the body. My intellect warred against this side pork while my heart and taste buds surged. I was again modern man at the banal crossroads where he always finds himself bifurcated like Rumpelstiltskin.

Naturally the side pork won. My art needed it, plus I knew that a simple bottle of Domaine La Tour Vieille would win the battle with pork fat if drunk speedily enough to get down the gullet to disarm the gobbets of side pork. To achieve health one must be able to visualize such things in terms of the inner diorama.

A number of doctors have been amazed that I am still alive, but the explanation is simple: wine. I started out in a deep dark hole being born and raised in northern Michigan which demographically is the center of stomach cancer in the United States. Up home, as it were, they love to fry everything and when short on staples they favor fried fried. To be frank, the French raised me, though I didn’t get over there until my thirties due to a thin wallet. Since my mid-teens I loved and read studiously French literature so that at nineteen in Greenwich Village I was scarcely going to drink California plonk while reading Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Apollinaire. Instead I drank French plonk at less than two bucks a bottle, slightly acrid but it did the job, which was to set my Michigan peasant brain into a literary whirl.

Whiskey is lonely while wine has its lover, food. Last evening here at a remote hunting cabin in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula we ate an appetizer of moose liver (excellent and mild), goose, and woodcock with Le Sang des Cailloux Vacqueyras, Domaine Tempier Bandol, and Château La Roque with Joe Bastianich’s Vespa Bianco with our cheeses.

Wine leads us to the food that becomes our favorite. It would be unthinkable for a Frenchman to eat his bécasse (woodcock) without a fine wine, say a Clos de la Roche, beside his plate, though this fine Burgundy is mostly affordable to moguls who unlike me don’t have the time to hunt woodcock, grouse, doves, quail, and Hungarian partridge. Since I love wild food and wine I have been kept active in the sporting life by these addictions. I will shuffle through the outdoors for hours to shoot tonight’s dinner though in the case of woodcock they are better after being hung for a few days. If the weather is too warm a forty-two-degree refrigerator works fine, though you keep your eye on how you rotate the birds. I’ve never had a woodcock turn “high” on me but you must be much more careful with the white-breasted grouse. I have frequently eaten the “trail” of woodcock, the entrails minus the gizzard, on toast, a French tradition that some of my American friends are squeamish about. I insist that the best cooking method for woodcock is to simply roast the birds over a wood fire making sure the breast interior is pinkish red. Much like doves and mallards an overcooked woodcock is criminal. Last year near our winter casita on the Mexican border I shot well over a hundred doves but when I cooked a few of them minutes too long my wife was utterly disgusted. Perhaps I did something truly stupid like answering the phone.

So wine fuels my sporting life but the hunting season ends and I become a bird-watcher rather than a hunter partly to keep moving and make sure my appetite is revved. Woodcock don’t freeze well but Hungarian partridge and grouse do, plus there are gifts from friends of elk, antelope, moose, and venison, which all cry out rather silently for red wine.

We had a nasty summer in Montana due to a two-month heat wave. I ate sparingly and shed ounces like dandruff, sensing that I was becoming too light on my feet for Montana winds. The heat forced me to drink whites, my favorites being Bouzeron and La Cadette’s Bourgogne blanc, their Vézelay blanc, too, and also a lot of lowly Italian prosecco which was amenable to the weather. My appetite recovered slightly when the garden flourished in August but it wasn’t until September that I could again fully embrace my first love, French reds.

The city of Lyon has kindly decided to give me a medal and is flying me over in a few weeks. Only by dint of tromping through forests and fields several hours a day can one be physically ready for Lyon, which makes me the man for the job. After each meal in Lyon I will climb the mountain, glance at the cathedral but not actually go inside, and then trot back down. Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon irritated me when in the second century he proclaimed animals don’t go to heaven because they can’t contribute monetarily to the church. I adore the classic bistros in Lyon, also a restaurant called Aux Fins Gourmets. These sturdy folks eat sturdily and I will ferret away a collection of fromage de tête (head cheese) in my hotel room in case I awake in the night disconsolate.

After Lyon I will positively reconstruct the nature of my blood in Narbonne, Collioure, and Bandol. Most intelligent people recall the established scientific victory of the Mediterranean diet over half a dozen others. The effect of the south is immediate. Once while writing for a week at the splendid Hotel Nord-Pinus in Arles, I became daily less somber and tormented so that what I wrote there was untypically jubilant. Doubtless if I wrote a whole novel in the south of France I would lose my winning reputation for melancholy. Once on the streets of Arles, for instance, I met a very undoglike lassie who was half-French and half-Egyptian. My knees buckled and I had to have two glasses of wine to make my way a mere block to the hotel.

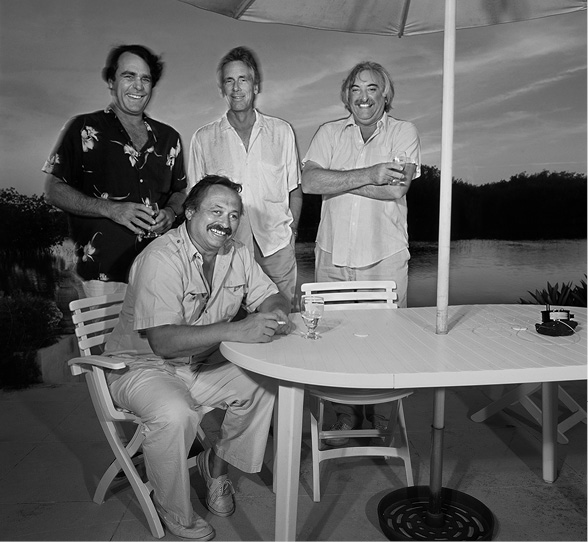

Our last evening at the cabin we had grouse and woodcock again, and a leg of lamb from my neighbor’s ranch in Montana. A friend, Rick Baker, brought along some Beychevelles from the 1980s, a Grand Cru Mondot from Saint Emilion, and more Domaine Tempiers. The Mondot was a little muddy, perhaps from shipment.

All in all it was a decidedly non-triumphant summer. In mid-September I made game pies from venison, mallards, doves, Hungarian partridge, ground veal, and pork fat with a lard pie crust. Superb. Unfortunately it was hot again and I had to eat one with a white Cadette. It worked, but in the middle of the snack it occurred to me that weather is God’s work while wine is man’s. René Char told us not to live on regret like a wounded finch. A few years ago a friend gave me an ’82 Pétrus and I swilled it before I learned I could have sold the bottle and bought a ticket to France where I’m closer to the heart of the matter, wine and its lover, food.