Of late I’ve determined that I am largely unfit for human consumption. We can think of ourselves accurately as five billion tiny fish swirling in a big green pond and I’ve only had passing contact with one in fifty thousand which seems more than enough. This idea came to mind recently when I finished the last stop on the last book tour of my life which came by happenstance in a foreign country, Canada, a somewhat alien and mysterious country to Americans. The pork sausage at the Park Hyatt in Toronto was the best in my long experience and I felt inclined to stay there indefinitely. Doctors recently have come to highly recommend the diet of pork sausage, room-temperature Swedish vodka, and the stray pack of airline peanuts found in one’s briefcase. If you crave greens you merely eat the leaves off the fresh flowers in your room. If they make you ill, stop eating them.

Toronto seemed like a good place to end a public literary career, partly because I felt at home in the many wooded ravines and kept a sharp single eye out for places I might pitch a tent and lay out my sleeping bag. In the United States these marvelous ravines would likely have been bulldozed long ago for no particular reason. One reason to live in a ravine is so you don’t have to go to the airport to fly home. Airports and office machinery lead the list of our current humiliations. Another reason to stay in Toronto is that the people are antiquely polite. I could see I wouldn’t be turned away at men’s clothing stores for being poorly dressed as I have been in New York City.

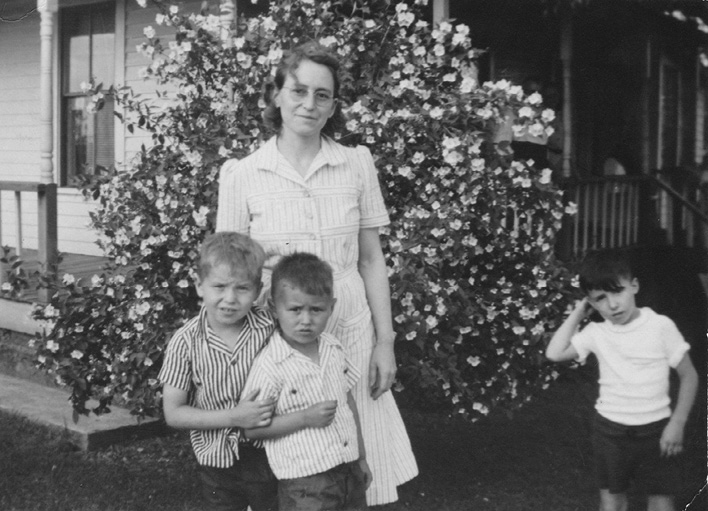

I’ve spent most of my life out in the water over my head and I want to come to shore if, indeed, there is a shore. Right after World War II, my father, grandfather, and uncles built us a cabin on a remote lake for nine hundred bucks’ worth of materials. The lake was about fifteen miles from our home in the county seat where my father worked as the government agriculturalist advising farmers. My uncles who had recently returned from the war were in poor shape in mind and body and so was I from a rather violent encounter with a little girl that took the sight from my left eye. My response, wonderfully close at hand, was to spend all of my time swimming and fishing and wandering in the woods. Every morning at breakfast my iron mother (of Swedish derivation) would say, “Don’t go out over your head.”

Consequently I’ve spent a lifetime doing so. There is a beauty in threat. A rattlesnake is an undeniably beautiful creature as is a pissed-off mountain lion, or a grizzly bear hauling off an elk carcass. The boy loves the icy thrill of taking a dare and running through a graveyard at night. Why not drop ten hits of lysergic acid and go tarpon fishing? Why not hitchhike to California with twenty bucks in your pocket? We can be perplexed and wanton creatures with all of the design of Brownian movement. When I begin a novel I always have the image of jumping off the bank into a river at night. There is no published map for the river and I have no idea where it goes.

Of course deciding to avoid the public doesn’t mean I’m going to stop writing my poems and novels, which are my calling. I’ve looked into the matter and it will be easy to Cryovac my work like those vain bodies suspended in liquid nitrogen and encased in aluminum tubes. They could have been stored in Saddam Hussein’s underground palace, but it turned out that our intelligence was in error and he didn’t have an underground palace.

Meanwhile, as I try to make my way to shore I have a number of significant projects and questions in mind, especially whether or not dogs have souls. Rather than stray off into the filigree of mammalian metaphysics my research into this question, already considerable, is dwelling on diet, with many clues coming from the coordinates in diet between humans, who presumably have souls, and dogs, who don’t—or so it was established by the Catholic Church in the ninth century when it declared that animals don’t have souls because they couldn’t monetarily contribute to the Church.

To start at the beginning we have to posit that reality is an aggregate of the perceptions of all creatures. This broadens the playing field. I was never a member of the French Enlightenment and most of my sodden but extensive education didn’t stick. All I recall from my PhD in physics at Oxford is that the peas were overcooked, the sherry was invariably cheapish, and that in the 1960s in England there were thousands of noisy bands with members wearing Prince Valiant hairdos. I survived on chutney and pork fat and the sight of all the miniskirts that rarely descended beneath the hip bones. No, all of my true education has come from the study of six thousand years of imaginative literature. As Andrei Codrescu said, “The only source of reliable information is poetry.” In addition I am widely traveled and have lived my life in fairly remote and vaguely wild locations where the natural world teaches its brutally frank lessons and where the collective media has no more power than a meadow mouse fart on a windy night. Prolonged exposure to nature gives one a sort of grammatica pardo, a wisdom of the soil.

Just the other day a woman, a rather lumpish friend, said to me over a lunch of squid fritters, “My life is so foreign, I wish it were subtitled like a foreign movie. Just this morning I noted that unlike me songbirds never seem overweight.”

“O love muffin,” I said, “life properly perceived is alien, foreign, utterly strange. If life seems familiar you’re afflicted with lazy brain. Birds don’t plump up because they have no sphincter muscle. They let go fecally on impulse. This would work out poorly in human concourse though it would seem appropriate in politics.”

A literary scientist must take note of disparate elements. In the very same newspaper the other day I noticed two important items. The world’s oldest man, a 113-year-old from Japan, said, “I don’t want to die.” (He’s evidently waiting for an alternative experience.) In the second article a young woman who is an ultramarathoner wasn’t feeling well and did thirteen “stop-and-squats” in a hundred-mile race that she won. It seemed a tad narcissistic to count, but more important she appeared to possess a genetic glitch that made her part bird.

Dogs have great powers of discrimination. They are said to have less than a quarter of the number of our taste buds, but this is more than compensated for by their vast scenting powers. Rover can be snoozing way out in the yard, but if you begin to sauté garlic he’s suddenly clawing at the door. The intense happiness you see in French dogs is doubtless due to superior leftovers. I noted that in over two decades at my cabin, my bird dogs were Francophile. They loved Basque chicken, the heavy beef stews called daubes, cuisse de canard which is a wonderful duck preparation from southwest France, and Bocuse’s bécasse en salmi, a rather elaborate woodcock recipe. It should be said that during hunting season it is hard to maintain the weight and strength of an English setter or a pointer. If you’re walking five miles a setter or pointer might cover thirty-five if it’s high-spirited. Compared to Labradors, setters can be finicky eaters. One of mine named Rose learned to refuse Kraft parmesan in favor of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Labs, however, show their love of nature by eating it. My Scottish Lab, Zilpha, loves to eat the gophers caught by her housemate, an English cocker named Mary. I’ve tried without success to rescue cheeping gophers from Zilpha’s capacious mouth. She loves green apples though they make her intestinally restless. This omnivorous capacity can be a problem as a recent X-ray showed that she was failing to digest some deer hooves. She is an obedient bird dog and we had a grand dove season along the Mexican border, though she pretended she couldn’t find the last bird of the year and on opening her jaws I found the feather evidence. Zilpha, however, is not in the league of a previous Sandringham Lab who once made it in a hip cast to the top of the counter and ate a bunch of bananas, a pound of butter, and a dozen eggs (in the shell).

We had a bitch Airedale named Jessie whose favorite snack was snakes, which she would catch and shake into manageable pieces, while another Airedale, Kate, never got beyond voles, popcorn, and pizza crusts in her preferences. A squeamish French Brittany who fishes with us likes Spanish Zamora or eight-year-old Wisconsin cheddar but will not touch fine salami because it is an Italian product. His name is suitably Jacques and he refuses chicken and pork but is frantic for beef in a hot Korean marinade.

But do dogs have souls? Of course they do for reasons I have delayed. Many scientists like myself have wondered at the sheer number of androids that have infiltrated our population. The obvious test is the absence of the belly button but a primary diet of fast food is also a good indicator. You can also add as evidence the reading of fast food–type books—99 percent of all published books here in the United States—and the predominance of television in their lives. The average bitch mutt is an absolute Emily Dickinson of the soul-life compared to the large android portion of our population.

In this slow swim toward shore I have been considerably impeded by my defect of Lab-like eating the world. I mean not just the food but every aspect of life on earth. My esteemed mind doctor of thirty-five years has been helping me banish this nasty habit. As a literary scientist I must remember that our work disappears quickly like a child’s money at the county fair. A certain austerity is required if I’m ever to touch the bottom. Never again will I eat a fifteenth-century recipe, a slew of fifty baby pig noses a dear friend in Burgundy prepared for me. It did look peculiar with all of those tiny nostril holes pointing toward the heavens beyond the kitchen ceiling. His Alsatian, Eliot, had scented these noses when they were still in the refrigerator and was frantic for his portion.

In order to sense the rather obvious souls of dogs we must first admit that much of life is inconsequential, a matter of frying eggs over and over, moment by moment, or daily playing “The Flight of the Bumblebee” on an accordion at an amateur show. This is because we’re seeing life from our own point of view. In order to clearly see a dog’s soul you must give up the hopeless baggage that is your personality. Dogs and other creatures are made nervous by our errant personalities that herky-jerkily infest the atmosphere. Forget your ninny self-profile and become accepting as your dog. You must totally absorb the dimension of stillness to fully meet the otherness of this creature, at which point you’ll have at first what you think is a metaphysical experience, and later realize is a birthright because you are nature too. Not surprisingly this attitude or state of being is also of great advantage in writing poems or novels, or cooking. Why get in the way of the actual ingredients? I’m not saying this is easy. It took me fifteen years to get a flock of Chihuahuan ravens to take a walk with me down on the Mexican border. Until last April I was properly on probation.

Once within the lucidity of extreme grief I was lucky enough to see the soul of a dog. She was in extreme pain and we rushed her to the vet in the middle of the night. I was holding her big body in my arms as if she were Juliet or Isolde and after the fatal injection I saw her soul shimmer out of her body. Frankly, the vision was a little banal like a science fiction movie but life is like that.