3

The Information Society or the Liberal Remodeling of Development Theories

“There is a difference, there are wealth gaps, but the North/South categories are too broad to account for it” (Hancock 2007).

Economic liberalization of the media has spread to most countries in the South, even among the most authoritarian regimes. In this respect, the Arab media system can be considered as an enlightening case study. This will help us to describe more precisely and concretely – to make tangible – the extension of the historical movements at present (described in the previous chapter). This system includes all the media of a wide range of countries and has been subjected to significant and diverse forces over the past three decades, which have significantly altered its trajectory. Let us remember that the regional (or pan-Arab) level is relevant because the Arab media is a system in the sense that their evolutions are interconnected. From a structural point of view, it is difficult to understand the media in a given country without reference to other media in the region as they share the same audience or, from the point of view of advertisers, the same market.

The dynamics we are trying to report on are complex because they cover diverse countries politically and economically, and involve various actors and processes – economic, social, legal – which finally take place over a fairly long time scale. In addition, in recent times, the system has been further enhanced by the integration of digital media, which has enriched national media systems and opened direct gateways, unimaginable a few years ago, to media in other countries and regions.

However, describing and explaining is not impossible, as long as appropriate analytical methods and tools are used. It is a question of avoiding the “orientalist” pitfall to analyze the media for what they are and in the tangible context in which they are deployed, more than through the prism of our representations. It is then possible to find an overall coherence. Moreover, from the media’s point of view, Arab countries are part of a global movement to modernize infrastructure and are open to the principles of liberal ideology that aim to give greater prominence to private sector actors. In this respect, the World Summit on the Information Society was an important milestone. As an avatar – and perhaps the last resurgence to date – of the developmentist approach discussed above, it highlighted the importance of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in economic and social development.

But moving away from culturalist approaches is sometimes equivalent to taking barren paths, such as those of the economic approach, which will be invaluable to us in this chapter. Thus, the statistical indicators defined at the end of this summit, and used in the Arab countries as well, allow us to give concrete elements of description that illustrate the modernization of infrastructures. As with any other region or country, media development depends on – or is determined by – important economic or demographic factors. These include the literacy rate, the importance of youth in the population, and also the difficult situation of labor markets which, once clarified, make it logical, almost self-evident, to develop digital media and in particular social networks. The analysis of social networks confirms that young people in Arab countries do not have politics or religion as their main concerns – rather socialization, music and culture in general, videos, job search, etc1.

The development of a media sector is not a coincidence: it is driven directly by governments or, on an unprecedented scale in media history, by major industrialists. There are all kinds of reasons for the changes, including the desire to capture the “crux of the matter”, namely the advertising manna. Like the other indicators, the systematic data are relatively recent, but their study is instructive. It shows the immature nature of the advertising market, which is still underdeveloped, but whose evolution is generally in line with what can be seen elsewhere: on the one hand, the domination of television as a medium, and, on the other hand, the very high growth rates of advertising on digital media. Despite the relatively low advertising revenues, the commitment of governments is real. They are trying to radically reform their media systems, either directly (see also Ayish 2010) or through the efforts of many businessmen – whose political position is often ambiguous2. There are many obstacles on this path; the habits adopted or the path dependence – to which we will return – is difficult to overcome because it requires going against habits and interests rooted in the history of institutions.

3.1. A global trend: the paradigm of a more “inclusive” information society

The economic liberalization of the media in the countries of the South has been announced in Tunisia. In the wake of the Internet revolution (and later the bubble) of the late 1990s and early 2000s, the World Summit on the Information Society was held under the auspices of the International Telecommunication Union. In fact, as early as 1998, the ITU Plenipotentiary Conference (the representatives of Member Governments) instructed the ITU Secretary-General “to place the holding of a World Summit on the Information Society on the agenda of the United Nations”, the aim of which would be “to establish a global framework identifying […] a common and harmonized understanding of the Information Society, […] to develop a strategic action plan [objectives to be achieved, methods to be implemented] for the concerted development of the information society […], and to identify the roles of the various partners for effective coordination of the implementation of the information society in all Member Governments” (Minneapolis 1998). The ITU Secretary-General was responsible for ensuring the preparation of this summit in coordination with other international organizations (Minneapolis 1998), a summit to be held under the patronage of the United Nations Secretary-General.

Two fundamental differences could be noticed with the summits of previous decades, in which governments were the major actors: on the one hand, it brought together international organizations, private multinational companies and civil society institutions, and, on the other hand, it was led by the United Nations Agency for the Development of Information and Communication Technologies. It is no longer under the aegis of culture and politics, but under the aegis of technology and innovation, that the place, role and development of the media were conceived and organized under (Frau-Meigs et al. 2012). The summit was held in two phases: in Geneva in December 2003 and in Tunisia in November 2005. The Geneva Summit Declaration of Principles proclaim, “the desire […] to build a people-centered, inclusive and development-oriented information society” (ITU 2003). The challenge is to take advantage of the opportunities offered by ICTs in support of the development goals set out in the Millennium Declaration3.

Ten objectives were defined by the action plan following the Geneva Summit (an 11th was added in 2010)4:

- 1) connect all villages to ICTs and create community access points;

- 2) connect all secondary or higher education institutions and primary schools to ICTs;

- 3) connect all science and research centers to ICTs;

- 4) connect all public libraries, museums, post offices and archives to ICTs;

- 5) connect all health centers and hospitals to ICTs;

- 6) connect all public administrations, local and central, and provide them with a website;

- 7) adapt all primary or secondary school curricula to meet the challenges of the information society, taking into account the specific conditions of each country;

- 8) to provide all the world’s population with access to television and radio broadcasting services;

- 9) encourage the development of content and create the technical conditions to facilitate the presence and use of all the world’s languages on the Internet;

- 10) ensure that more than half of the world’s inhabitants have access to ICTs within reach;

- 11) enable all companies to have access to ICTs.

3.2. Progress: an accounting measure?

The previously mentioned paradigm shift – primacy of technology, liberal ideology – is evident in the post-Summit period: once the objectives have been defined, “progress” must be measured. It is therefore in order to “measure the information society” that a Partnership for Measuring ICT for Development was established in 2004, aimed in particular to coordinate the activities of regional and international organizations in the field of measuring ICT diffusion. This Partnership (bringing together, around ITU, major UN agencies such as UNESCO and UNCTAD, as well as OECD or WHO, and many others) has defined a list of 60 key indicators to help developing countries produce official ICT statistics (original list in 2004, extended in 2012 and then in 2014). Reflecting the normative spirit of the Summit, these indicators are intended to serve as guides for the implementation of public policies in this area (collection of statistical data, investment objectives, etc.). These data are also intended to allow an international comparison of developments in different countries and finally to provide a measure of the digital divide between rich and poor countries, and within poor countries, between cities and the countryside. The list has been used as a basis for the collection, since 2005, of national statistics that have the merit, when available, of being comparable (provided they are handled with care). The Partnership has also set itself the role of monitoring the WSIS objectives.

The year 2015 had been defined in the Tunisia Agenda as the target date by which the WSIS goals should have been achieved. The objectives were particularly ambitious if not utopian; not surprisingly, they were not achieved. However, some general principles of interesting actions to be noted were affirmed on this occasion and in the forums that followed: the importance of ICTs as vectors of economic and social development, and the centrality of information and communication (of which the media is only one component) in all social processes.

Referring – as Western delegations did during the NWOIC debates – to Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Summit Declaration of Principles states that “communication is a fundamental social process, a basic human need and the foundation of all social organization. It is central to the information society. Everyone, everywhere, should have the opportunity to participate and no one should be excluded from the benefits the information society offers” (ITU 2003). The information society thus becomes a global concept: participation becomes a fundamental right of the individual, with beneficial effects on many aspects of social life. On a scientific level, for example, the sharing of knowledge and the sharing of research would promote the technical and scientific progress that makes the information society possible (thus having a beneficial effect on innovation and ultimately on employment). In addition to their ability to promote scientific progress, entrepreneurship and human well-being, ICTs would have an impact on almost every aspect of our lives and would make it possible to achieve higher levels of development – not unlike the theories of modernization of the 1960s and 1970s, which have shown their limits. Economically, ICTs could, under favorable conditions, increase productivity and thus stimulate economic growth and job creation5.

On the basis of these assumptions, the Summit concludes that it is essential that the development of ICTs – with a view to establishing the information society – should be one of the priority objectives of developing countries. The establishment and management of these investments should be carried out according to a liberal model (public/private partnerships6), more than through official development assistance7. The role of governments is “the development and implementation, at the national level, of global e-strategies”. In particular, it is recommended that “developing countries should intensify their efforts to attract significant domestic and foreign private investment in ICTs, by creating a transparent, stable, and predictable environment conducive to investment” (Minneapolis 1998, p. 17). As for the private sector, its “commitment […] is important for the development and diffusion of information and communication technologies (ICT), in terms of infrastructure, content and applications” (Minneapolis 1998, p. 1). The pendulum effect – disengagement of governments/rise in power from the private sector – is clear and is imposed on all countries as a natural modus operandi.

As has been said, this attempt to describe or characterize “the post-industrial society” (or more simply to measure the tremendous technological advances of the past three decades) is a utopia similar to those of the 1950s and 1960s. The concept of the information society appears to be more of a global project than a description of how societies actually work. It is marked by a very strong technological determinism (Neveu 1994) that we could compare to the others that preceded it, from the utopias of cybernetics to those of the role of the media in development, then those that are closer to us, with the capacity of the Internet to revolutionize the economy. The formulation of some objectives is also reminiscent of the objectives previously assigned to radio and television for rural education in developing countries8, but the project here is much broader: coordination of policies and investment effort, ambition – and above all uniformity – of objectives and the variety of actors involved.

May 17 has been declared as the World Information Society Day by the UN General Assembly9. The theme of the 2016 edition, for example, was “Entrepreneurship in the ICT sector for social progress”. The presentation page states that “ICT entrepreneurs, start-ups, and small and medium-sized enterprises (MSEs) play a key role in ensuring sustainable and inclusive economic growth. They participate in the development of innovative ICT-based solutions” (ITU 2016). It is also recalled that this day is part of ITU’s activities to “unleash the potential of young entrepreneurs in the ICT sector while focusing on MSEs in developing countries (ITU 2016)”. In reality, the development of this sector has led to the unquestionable domination of American, Japanese, and European multinationals, given the technological know-how and financial power that this implies10. The choice of opting for a liberal economic model in the development of the information society – at the expense of potentially corrective action by public authorities – will hardly be able to reverse this trend. Moreover, developing countries are currently mainly growth markets for companies in more economically advanced countries, and ICT growth is now emerging as a consequence of, rather than a cause of, economic development. Thus, Immanuel Wallerstein’s theory of dependence, distinguishing between dominant countries (the center) and others that depend on it (or the periphery), may not be obsolete (Wallerstein 2006 and see also Amin 1973, p. 365).

The media occupy a minor place in the declaration of intent (which is a reminder of some general principles), but the action plan drafted after the summit is much more explicit about their role. It states that “the media – in their various forms and regardless of ownership – have an essential role to play in building the information society and are recognized for their important contribution to freedom of expression and pluralism of information”11. This point raises important questions, in particular the fact that the existence of the media can only contribute to freedom of expression if the public authorities tolerate it. Indeed, the action plan recommends action at the level of national legislation to guarantee the independence and pluralism of the media. In addition to societal objectives (promoting a balanced image of men and women, combating illegal and “harmful” content, reducing the “knowledge divide” by facilitating the flow of cultural content to rural areas), two important international projects have been formulated:

- 1) Encourage media professionals in developed countries to develop partnerships and networks with their counterparts in developing countries, particularly in the field of training.

- 2) Reduce imbalances between nations in the field of media, in particular with regard to infrastructure, technical resources and human skills development, making full use of ICTs in this regard.

The purpose here is not to criticize the concept of the information society, even though its non-neutrality is obvious12, and the actual results of its implementation uncertain13. What is important here is, on the one hand, the comparison with previous projects with a global scope to highlight their sometimes-utopian character. This is not to deny the benefits of the widespread diffusion of digital media but to avoid the trap of the illusion of the power of citizens. It is therefore risky to formulate globalizing considerations – involving all societies in all their components – based on the indisputable observation that modern means of communication are an asset for knowledge and economic development. The social and political impact of ICTs depends above all on the context in which they are deployed and on what social actors do with them (governments, citizens, companies, trade unions, political parties, journalists, etc.). With regard to the media, giving them an a priori role, from above – while their role and place in society are more the result of their use – even appears, to a certain extent, to be in contradiction with the principles of stated freedom. Ultimately, we see that the technological determinism of previous waves of innovation is tough in ICT and media: all it would take is for technology to be available for development, literacy, growth, etc., to take place14.

On the other hand, it is a question of showing that Arab countries are caught up in a global movement that greatly structures their investment effort. The examination of our case study, the Arab media system, will provide a concrete illustration of the global trends affecting the media. The figures we are going to use for Arab countries are part of the indicators that the Partnership for the Information Society have defined following the WSIS.

3.3. Arab countries in the “information society”

In terms of Internet access, ITU estimates that in 2017, Arab countries were on a par with the Asian Pacific region with just under 44%15 of people using the Internet (the world average is 48.0%), which is well below the developed economies (81%). A similar picture emerges for the percentage of households with Internet access (47.2% for Arab countries and 48.1% for Asia, growing faster), again below the developed economies (84.4%) and also compared to the world average (53.6%). This means, incidentally, that nearly one in two people in the world did not have access to the Internet in 2017: the 10th objective (half of the world’s population has access to ICTs) has been achieved overall, but access disparities is very large between regions. For these first two indicators, Africa is quite clearly behind (only 21.8% of people have access to the Internet, and 18.0% of households) – proof that the digital divide is far from having been bridged, and that the achievement of a quantitative objective does not mean that the targeted imbalance has been corrected. Within regions, men have more access to it than women; the gap widens as income declines, and the gaps are large between urban and rural areas.

For mobile broadband telephony, in 2016, there were 47.6 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in the Arab countries, roughly in line with the world average (49.4 ab./100 inhabitants), but well below the average for developed countries (90.3 ab./100 inhabitants). In addition to the lack of infrastructure, the cost of broadband remains too high for large-scale dissemination: in the majority of developing countries, the price of broadband exceeds the 5% of revenue threshold defined in 2011 by the Broadband Commission for Digital Development16.

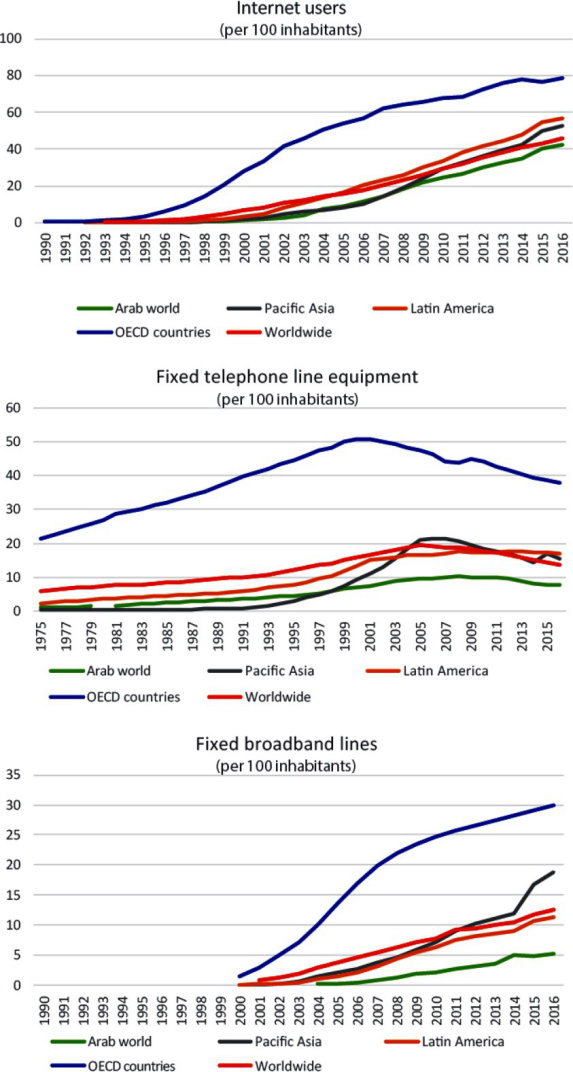

The following graphs illustrate the evolution of four indicators (most recent date: 2016).

Figure 3.1. Access to the world’s communications media

(source: World Bank). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/guaaybess/media.zip

Thus, overall, Arab countries are “connected”. We see the same decline in fixed phones, with individuals preferring the freedom and discretion of mobile subscriptions, especially since the cost of mobile broadband is now more than 50% lower than the cost of broadband via fixed lines (ITU 2016b). The rate of growth of broadband subscriptions in the Arab region has been very rapid, as can be seen in the last graph. Mobile phone penetration increased by an average of 23% per year between 2000 and 2016, compared to a global average of 13% per year. Apart from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (which already have very high equipment rates), and Lebanon, the growth in mobile phone penetration has been faster than the world average in all countries in the region. Internet use and fixed broadband subscriptions have also spread in the Arab region at a higher rate than the world average, and this has been observed in other developing regions (Pacific Asia, Latin America).

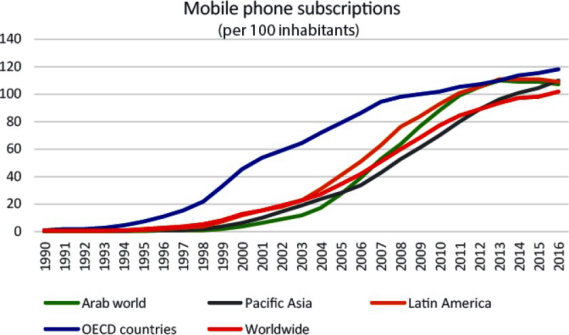

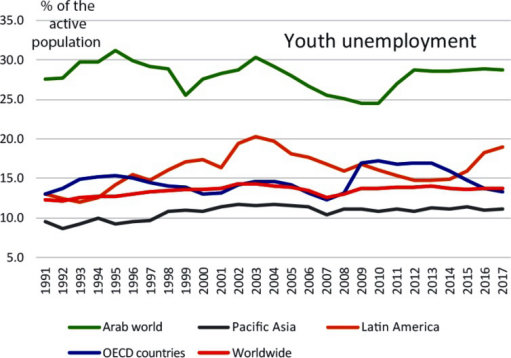

Finally, for computer equipment, the Arab region has taken off (see the following graphs). The Commonwealth of Independent States is characterized by a very high rate of equipment growth. The Arab region is also doing well, despite the economic and political difficulties following the Arab uprisings, which have only slowed a rapid pace of progress. This is therefore a fundamental trend.

Figure 3.2. Computer-equipped households in Arab countries and around the world

(source: ITU). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/guaaybess/media.zip

The disparity in national situations is great, as shown in the following table for a few countries:

Table 3.1. Rate of computer equipment in various Arab countries

(source: ITU)

| Computer equipment percentage | Year | |

| Algeria | 37.0 | 2015 |

| Saudi Arabia | 69.0 | 2016 |

| Bahrain | 94.8 | 2016 |

| Egypt | 55.8 | 2016 |

| United Arab Emirates | 91.0 | 2016 |

| Jordan | 47.0 | 2014 |

| Kuwait | 80.7 | 2013 |

| Lebanon | 71.5 | 2011 |

| Morocco | 54.9 | 2016 |

| Oman | 82.9 | 2013 |

| Qatar | 88.3 | 2015 |

| Sudan | 14.0 | 2012 |

| Tunisia | 39.3 | 2016 |

This technological upheaval has not been imposed by governments: the above developments reflect both changes in behavior and a demand for new information and communication technologies by individuals. Demographic and economic factors have been at the root of these changes. And, if these have been so rapid, it is also because of a social context that has created new needs among citizens.

3.4. Young graduates – and connected in a precarious economic context

As a general rule, users of new technologies are among the young people in a given population (age groups up to 50 years). They are more urban, and with higher than average levels of education – and often income – than average. ITU data for each country clearly shows the link between the level of economic development and access to media.

Significant progress has been made in literacy, with Arab countries having succeeded in closing a significant part of their gap. The literacy rate in the region has increased from 65.9% in 2000 to 77% in 2010; the world average has also increased, but at a slower pace because it starts from a higher level (from 81.9% to 85.2% over the same period). It is naturally young people’s literacy that has driven the whole, since the rate has risen from 81.6% in 2000 to 88.7% in 2010, which is no longer far from the world average (90.6%). It should be noted that there are significant disparities at two levels: between boys and girls first, since 91.6% of boys are literate compared to 85.7% of girls. There are also disparities within countries: not surprisingly, given their level of per capita income, the Gulf countries (but also Jordan) have rates above the world average (from 94.4% for Saudi Arabia to 97.9% for Jordan), while Egypt, for example, is at 75.1%, and Syria at 85.5%.

The demography of Arab countries is also favorable to media development. Indeed, Arab societies are young. People under 14 years of age represent 33.2% of the population, while the world average is 26.1%. This is by far the highest percentage among the regions mentioned (20.3% in Pacific Asia and 26% in Latin America17). Moreover, the decline in this rate (population aging) is much smaller than elsewhere. Similarly, the number of people over 65 is the lowest (4.3%, compared to a world average of 8.3%), and this percentage has not increased much over the past two decades. These young people are particularly literate: very often more than 90% of them are literate, even outside the Gulf States and Jordan and Palestine. The global average is often far exceeded; moreover, in countries spared by war and where the literacy rate was relatively low, countries have often experienced faster rates of growth than the global average, as shown in the following table (gains expressed in percentage points per year).

Table 3.2. Youth literacy rate

(source: World Bank, our calculations)

| Youth literacy rate | |||||

| Middle of the 2000s | Recent period | Average yearly increase | |||

| Percent | Year | Percent | Year | ||

| Arab world | 81.6 | 2000 | 88.7 | 2010 | 0.71 |

| Global | 87.3 | 2000 | 90.6 | 2010 | 0.32 |

| Algeria | 90.1 | 2002 | 93.8 | 2008 | |

| Bahrain | 97.0 | 2001 | 98.2 | 2010 | |

| Comoros | 80.2 | 2000 | 86.8 | 2013 | 0.51 |

| Egypt | 84.9 | 2005 | 92.0 | 2013 | 0.89 |

| Iraq | 84.8 | 2000 | 71.6 | 2012 | |

| Jordan | 99.1 | 2003 | 99.1 | 2012 | |

| Kuwait | 99.7 | 2005 | 99.3 | 2015 | |

| Libya | 99.6 | 2004 | 99.9 | 2013 | |

| Mauritania | 61.3 | 2000 | 56.1 | 2007 | |

| Morocco | 70.5 | 2004 | 91.2 | 2012 | 1.58 |

| Oman | 97.3 | 2003 | 98.7 | 2016 | |

| Qatar | 95.9 | 2004 | 98.7 | 2014 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 95.8 | 2004 | 99.2 | 2013 | 0.37 |

| Sudan | 78.2 | 2000 | 65.8 | 2008 | 0.79 |

| Syria | 92.5 | 2004 | n.d. | ||

| Tunisia | 94.3 | 2004 | 96.2 | 2014 | 0.42 |

| United Arab Emirates | 95.0 | 2005 | n.d. | ||

| Palestine | 98.9 | 2004 | 99.4 | 2016 | |

| Yemen | 76.9 | 2004 | n.d. | ||

More generally, the demographic transition18 was in operation until the mid-2000s. The fertility rate, which fell from 6.8 children per woman in 1970 to an average of 3.5 children per woman in the region in 2005, has stabilized at this level: this stabilization hides various national situations (the region is far from being homogeneous) (Courbage 2007).

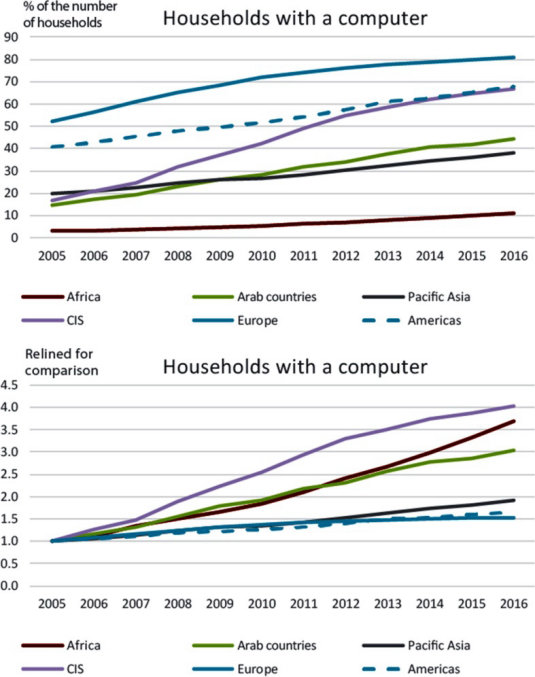

If there is one area where the region does not stand out positively, it regards employment. Youth unemployment remains very high, which is a very powerful motivating factor. According to the World Bank, it stood at 28.7% in 2017; by way of comparison, the world average is 14%. And it is increasing, further contrasting with the overall employment dynamics where youth unemployment is stable or even declining in some regions. Another important element is the unemployment rates by level of training. Where, in developed countries, graduation reduces the risk of unemployment, the opposite is true in Arab countries where the labor market struggles to absorb university graduates. In the Euro zone, for example, unemployment among university graduates varies between 15 and 20%, but it is generally close to 30% or even higher in the Arab countries19. Finally, the gender gap is very large: while 24.5% of men aged 15–24 are unemployed in the Arab countries, this rate is 43.2% for women, which is by far the largest gap in the regions we cite for comparison (overall, the unemployment rate for young men is 13.1% and for young women 15.6%). Gender inequality in employment is, of course, reflected in the region’s population, where the unemployment rate for women is twice as high as that for men (19.4% compared to 8.8%)20.

Figure 3.3. Youth unemployment. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/guaaybess/media.zip

One of the consequences of the developments we have presented is the rapid development of the media sector, whether it is:

- – at the global level with projects implemented by international organizations of which the countries of the region are members, and which strongly encourage investment in ICTs;

- – or at the local level with the growth of income levels; the importance of young people in society; the increase in literacy, especially among young people – who also face significant economic (unemployment, housing, etc.) or political (freedoms, political representation, etc.) difficulties.

In a very schematic way, public policies result in the development of infrastructure, which opens up access. The literacy of citizens, their relative enrichment and the demographic structure are permissive conditions for the use of these infrastructures. The economic and social context provides the motivation for use and determines it. In the end, a virtuous circle from the point of view of the growth of the sector can be set up, with the arrival of advertisers who will influence the supply of content and media, both by the public authorities and by the private actors involved.

ITU has developed a synthetic indicator that groups the main ICT statistics into three categories (access, use and skills)21. Table 3.3 shows the evolution of this indicator between 2010 and 2017. We see that the improvement in the Arab countries is one of the strongest.

Table 3.3. ICT Development Index

(source: ITU 2017b)

| 2010 | 2017 | Variance | |

| Europe | 6.5 | 7.5 | 1.0 |

| CIS | 4.4 | 6.1 | 1.7 |

| Arab states | 3.9 | 4.8 | 1.0 |

| Americas | 4.2 | 5.2 | 1.0 |

| Pacific Asia | 3.9 | 4.8 | 1.0 |

| Africa | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.8 |

3.5. The use of digital media and social networks

The media that have attracted the most interest in recent years have been digital media and in particular social media, of which social networks are an important component. It is mainly the latter that have attracted the world’s attention, and for good reason: their penetration rate in the region has increased at a very rapid rate. According to figures published by the Dubai School of Government, which monitors the use of social networks in Arab countries, there were about 11 million Facebook users in the Arab world by 201022. This figure has risen to more than 156 million in 2017 – almost 16 times more. These users represent 38% of the region’s inhabitants and more than 90% of its 150 million Internet users23. And Facebook is not the only one. A survey conducted by TNS24 in different Arab countries showed that the two most used networks were Facebook (87% of respondents) and WhatsApp (84%). In third place was YouTube (39% of respondents), then Snapchat (34%) and finally Twitter (32%).

Users are mainly young people (for Facebook, for example, the 15–29-year-old range are in the majority in all countries except Kuwait, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, and they represent more than 60% of users in 12 countries). 68% are on average men in the region25, but there is a significant disparity in this regard when looking country by country. Broadly speaking, for the Levant countries and North Africa, we remain at approximately 65% of male Internet users, but for the Gulf countries, this rate is rising to 75%26. The two dominant languages are Arabic and English (Table 3.4 is related to Facebook).

Table 3.4. Languages used on the Internet in the different Arab countries

(source: Arab Social Media Report 6th (June 2014) and 7th editions (2017) (Dubai School of Government 2018))

| Arabic | English | French | |

| Yemen | 95 | 13 | 0 |

| Libya | 93 | 22 | 2 |

| Palestine | 94 | 25 | 1 |

| Iraq | 93 | 24 | 1 |

| Egypt | 94 | 34 | 4 |

| Jordan | 90 | 38 | 2 |

| Somalia | 16 | 98 | 2 |

| United Arab Emirates | 18 | 88 | 2 |

| Qatar | 21 | 87 | 2 |

| Bahrain | 25 | 81 | 1 |

| Kuwait | 32 | 78 | 1 |

| Lebanon | 32 | 78 | 10 |

| Oman | 40 | 69 | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 48 | 60 | 1 |

| Tunisia | 18 | 15 | 91 |

| Morocco | 33 | 13 | 75 |

| Algeria | 32 | 11 | 76 |

| Mauritania | 48 | 11 | 59 |

With regard to the preferred language of use on the Internet, Arabic comes first with 58%, English second with 32% and French third with 9%27.

As for uses, they do not correspond to certain representations. The context that Arab bloggers are known for around the world (see for example Salam 2014) (due in part to the readings) by European media is that the main use of social media is political. This is not really surprising, given that these are the “Arab revolutions”, a period of strong political and social mobilization (Guaaybess 2015). However, according to the TNS study, it appears that the motivations of young Arab Internet users are not fundamentally different from those of Internet users in other regions: making contacts, chatting, reading news feeds or blogs, searching for friends or family, sharing photos or videos, getting informed, having fun, etc., are all motivations that come well before the discussions on current events28. To continue the comparison with France, there are, of course, differences that reflect societies at different stages of economic development: for example, consulting your bank account on the Internet, searching for restaurants or cafés and shopping online are practices that are not yet fully integrated into the daily lives of young people in the Arab countries, for obvious reasons (per capita income, banking, etc.).

The TNS study shows that the main virtues recognized by Arab Internet users on social media are related to their ability, real or perceived, to create social ties and to promote personal development (creativity, free expression, more effective means than traditional media in job searches, etc.). As for the use of social networks, here are the main findings from the study, The Arab World Online29:

Table 3.5. Uses of social networks in Arab countries (trends)

| Favorite uses | |

| Social/hobbies | 46% |

| Work | 25% |

| Education | 9% |

| Business | 8% |

| Information seeking | 6% |

| Social issues | 4% |

| Political activism | 1% |

This is quite far from the representation that the use of social media is exclusively for political advocacy purposes.

In terms of frequency of consultation, it is daily for more than 95% of Internet users connected to a social network. And finally, the consultation is overwhelming on the mobile phone, for 83% of respondents (11% for laptops). In this, Arab Internet users are following a global trend that is also observed in economically developed countries, namely the growth of mobile connections to social networks and the Internet.

At a more general level, the main obstacles to Internet access are first and foremost the quality of the connection and the existence of a network (cited by 48.4% of respondents30), the cost (44.7%) and the lack of Arabic language content (40.8%); 33.5% cited censorship or blockages by public authorities, which is a very high rate even though it is not the main factor.

3.6. The advertising market, between certain delay and rapid growth

The elements presented in the previous sections mainly reflect new ways of using the media. They show the dynamism of the sector, whose development was first led by the governments, and then, in recent years, the gradual involvement of the private sector. The media is also an economic sector, generating significant revenues through the rental of infrastructure (satellites, etc.) or, from the point of view of content, through advertising or pay-tv. The figures on advertising revenues are interesting because they give a clear idea of the social importance of the media in relation to each other, beyond the effects of “one” or of fashion effects. We also see the degree of maturity and growth potential of one medium in relation to the others.

Consider a mature advertising market like the United States. In 2015, advertising generated a turnover of 183 billion dollars31 (in a $531 billion global advertising market32). Television advertising generated 37.7% of this revenue; the second largest source of revenue is digital media with 32.6% of the total. The written press generated 15.4% of the total. In 2017, the balance of power is expected to reverse, with digital media accounting for 38.4% of the total, compared to 35.8% for television, and 12.9% for the press.

Other sources agree that, in 2017, it is not only in the United States, but also worldwide that digital media advertising will take precedence over television33. In 2017, the global advertising market is expected to reach $603 billion: of the expected $74 billion in growth, $64 billion will be generated by digital media. Internet advertising revenues will thus grow by more than 15% per year, more than three times the growth of the sector as a whole (less than 5% per year is expected).

In the Arab countries, the situation is very different. The advertising market is rather modest: at $5.5 billion34. Political instability following the Arab uprisings has had a negative impact on advertising revenues since 2010, which have grown at a rate of 2%, half the global rate35. There has been a decline in the speed of advertising on traditional media (as elsewhere in the world) and digital media have not been able to compensate for the loss of this revenue. The largest advertising market in the region is not a country, but a so-called “pan-Arab” segment; it is the transnational messages broadcast on different media (mainly television and digital, but also part of the press) throughout the region, which generates 50% of its advertising revenue. The second most important market is the United Arab Emirates, which is on a par with Saudi Arabia with 11% of total revenues. Egypt, with its 90 million inhabitants, is third with 7%, ahead of Qatar (4%).

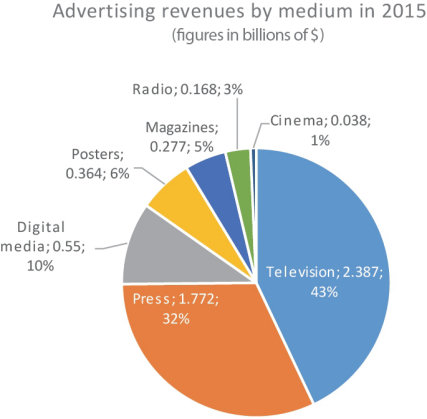

Another glaring difference is in the distribution by media, as can be seen in Figure 3.4: the press has twice as much weight as in the United States, and digital media has three times less weight. Thus, while consumers spend only 10% of their time on the press, it absorbs more than 30% of advertising resources. And while the smartphone penetration rate is particularly high, and 70% of ads are seen on mobile phones, they generate only 6% of advertising revenue36. This is partly due to the weaker ability to monitor Internet users’ behavior to define the right targeting (more generally, a lack of experience in digital marketing and rather simplistic strategies – lack of product placement, sponsorship and specialization of formats by media). Another reason is the important weight of governments on the market: governments bear 20% of the region’s advertising expenses, two-thirds of which are spent through the press, whose audience is mainly national (and not limited to the social categories described in the previous).

Figure 3.4. Advertising revenues by medium in 2015. N.B. The figures for the region. The situation varies greatly from one country to another

(source: Northwestern University in Qatar). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/guaaybess/media.zip

While the level of revenues generated on digital media is still low, the growth rate is very high: on average 39% per year between 2010 and 2015, rising from 2% of the region’s advertising revenues in 2010 to 10% in 2015. In comparison, advertising revenues on traditional media have increased by an average of 5–6% per year. This leads experts to estimate that digital media will surpass the press in 2020, 3 years after the United States.

This chapter has focused on an economic perspective. It is a necessary step towards understanding the underlying trends that structure the Arab media system, which is part of a global digital system. When the revolts broke out in 2010 and 2011, many analysts and journalists – including from Arab countries – attributed them to bloggers (Guaaybess 2017b). A careful analysis of the facts has enabled us to highlight a phenomenon that we have called the “media confluence”, in which the new media do not eclipse the old ones, but intertwine with them to give the system a new complexity and reactivity, more in line with the society it is a part of. We will come back to this in the next chapter. The media confluence is driven by social and political dynamics (student or workers’ movements, opposition and civil society organizations, etc.) that are more or less visible in Arab countries. The figures, the underlying trends concerning users, their access to the media and the media themselves in the Arab region, have limitations and cannot be sufficient, but they made it more tangible.