Chapter 8

Designing a Secure Exchange Solution

As a messaging consultant, you know that some of the most complex areas in designing a Microsoft Exchange solution are those relating to security. There are a number of reasons for this. Primarily, security and the technology used to address security considerations are a minefield and a discipline in their own right. This makes understanding security concepts and the ability to talk in the same language as your security officer a challenge from the outset. When and if you manage to overcome this hurdle, further frustration is likely to develop from a lack of requirements and the disparity between the vision and the reality of your design. You will then need to reason with and facilitate key stakeholders to identify and agree on a way to move forward.

More than any other area of the design of a Microsoft Exchange solution, determining how the solution is to be secured requires an array of skills. The goal of this chapter is to help you understand and develop those skills, from comprehending the concepts and vocabulary needed, to appreciating the functionality within Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 that can be deployed to meet the project's requirements. Deploying a secure Microsoft Exchange solution often relies on dependent infrastructures, so we'll discuss the wider infrastructure components in order to provide you with a thorough understanding of how a project's requirements can be met in full.

In addition, this chapter will provide you with useful insights to prepare you for the awkward questions from your security officer and enable you to elicit the security requirements in a concise manor, thus avoiding the lengthy and soul-destroying security workshops and the spectrum of confusion that will arise from that disparity between the vision and the reality!

Should you wish to skip this chapter, we urge you, at the very least, to read and understand the section “How Real Is the Threat Today?” This section alone should encourage you to read on.

Before plunging into the “how,” it is vital that you understand the “what” and “why.” That is, what is security and why is it important? How real are the security threats and risks to a messaging infrastructure today?

Because of a number of security incidents that have occurred since the first release of Microsoft Exchange Server, and with the onset of ubiquitous computing (the embedding of microprocessors in everyday objects), the meaning and significance of security have changed. Consequently, the technology used to avoid security risks and threats has also matured. As you will learn later in this section, message security is now integral to Exchange Server thanks to Microsoft's Trustworthy Computing (TwC) initiatives and Secure by Default principles.

Email is no longer accessed only from the workplace, using one device and one access endpoint. User demand, driven by ubiquitous computing, has created a need for flexible access and, of greater concern from a security perspective, a desire for uncontrolled access. Securing a messaging infrastructure implies securing email on a wide spectrum of devices and classifying and protecting data in motion.

When we speak about security, we are talking about risk acceptance and probability. It is the job of the security officer to assess the risk and probability of security threats and then to determine what must be done to avoid or mitigate those threats and risk. Consequently, securing a messaging infrastructure means different things to different organizations. As consultants, it is our job to understand the meaning of security for a particular organization and then decide how best to address it during design.

The financial impact of viruses spread during the early versions of Microsoft Exchange Server (and messaging systems in general) is estimated to be approximately $16.7 billion in labor costs, tool expense, productivity loss, and lost income. Since mid-2000, the impact of such mass-mailing viruses has been reduced. To eradicate mass-mailing viruses, such as “Anna Kournikova,” “I Love You,” and “MyDoom,” Microsoft addressed vulnerabilities within Outlook. More recently, the use of cloud-based message hygiene services has grown, providing a dynamic level of intelligence. As a consequence, antivirus software vendors have increased their capabilities in terms of identifying and reacting to viruses more quickly. In addition, many organizations have deployed edge antivirus protection. Although the impact of such viruses has been greatly reduced, other more insidious threats still remain.

Those of you who experienced the epidemic mass emailing of viruses may believe that the threat of email-related viruses has been eradicated. Delving into the statistics produced by antivirus software vendors shows that, on the contrary, the threat is still significant. The December 2012 issue of the Symantec Intelligence Report states that 1 in 277.8 emails contains malware (malicious software), 1 in 377.4 emails contains phishing attacks (the act of attempting to acquire information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details by masquerading as a trustworthy entity), and 70.6 percent of all email was reported as spam. By example, in an organization with 50,000 users, each of whom receives, on average, 10 email messages per day through the Internet, 500,000 messages in total inbound will be received from the Internet; of these, on a daily basis,

The probability of an attack depends on multiple factors including current level and depth of protection, the industry in which the organization operates, and the geographies in which the organization does business. Organizations based in the United States are more likely at risk than those in any other country. India and the United Kingdom also have a high probability of receiving emails containing phishing attacks because of the large installed base of technology found in those countries.

Aside from malware, spam, and phishing attacks, unauthorized access to network and email data is extremely prevalent today. In the majority of cases, hackers will use one of the following methods to gain unauthorized access to users' email accounts:

Over the last two years, fewer mass-mailing attacks have been launched as hackers focused on high-value cybercrime, such as spear phishing, that is, targeted attacks, directed at specific individuals or companies. In such cases, attackers gather personal information about their target to increase their probability of success. Since 2009, hackers have launched damaging cyber raids on multinational organizations such as Coca-Cola, BG Group, ArcelorMittal, and Chesapeake.

Coca-Cola's email system was infiltrated by an email sent to the deputy president of Coca-Cola's Pacific Group, appearing to come from the CEO. The email contained a malicious link, which when clicked, transparently began downloading malware including a keylogger, which records and logs the keys struck on a keyboard. The reported aim of the attack was to ex-filtrate files relating to Coca-Cola's ultimately unsuccessful $2.4 billion acquisition of China's Huiyuan Juice Group. It is clear that, although the impact of such threats is not as obvious as it was during the mass-mailing virus attacks, the threat is still very real, and a good security officer will be aware of current threats and methodologies, tools, and techniques used to penetrate corporate email systems.

As a messaging consultant, you must understand the likely security concerns of an organization so that you are adequately prepared to determine, communicate, and challenge (if necessary) the proposed security requirements.

During research conducted in April 2012, Mimecast, a company that developed a platform that uses cloud computing to deliver email management, held 500 interviews with IT decision makers across a range of company sizes, industry sectors, and regions. The June 2012 “Shape of E-mail” report concluded that while the level of concern regarding mobile and remote access to email is very real (39 percent and 41 percent of organizations, respectively, agreed), organizations are more concerned about email-based viruses (55 percent) and email security breaches in general (55 percent).

In August 2006, Microsoft classified the four major threats to a messaging and collaboration infrastructure as follows:

Although the threats have matured and are now more sophisticated than in 2006, this threat classification still applies.

Later on, we will take a look at the Microsoft Exchange functionality that can be used to secure the platform against such threats. For malware and spam, we will consider the new built-in functionality designed to provide protection alongside a cloud-based service. To address unauthorized network access, we'll look at how to secure external access, how to secure remote client access, and the options available to harden Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 servers. In the concluding section, we will consider data encryption (at rest, in motion, and long-term storage). Finally, should the integrity of the system be compromised, we'll consider the built-in auditing capabilities of Exchange Server 2013.

Conversations relating to security are almost always unpredictable. Despite this, it is essential that you win the trust of the security officer. If you understand the threats to the organization and have a firm grasp of the technology, you are halfway there. The aim of this section is to provide you with some useful insights so that you can become that trusted advisor.

It is vital that during the early design stages of an Exchange 2013 solution, you involve the security team, not just in collecting the security requirements but also by keeping them informed of your progress and ensuring that you gain an understanding of the organization's current security strategies. Keeping the security officer on board with the design can be the difference between the success or failure of the project. The security officer has the power to veto the project if they do not buy into the solution. It is not uncommon to see entire strategies fail, whether the strategy is Bring Your Own Device (BYOD), Exchange Online, or creating a dynamic/flexible work style, if the messaging consultant doesn't gain support from the security team from the start.

Over the last 10 years, the authors have held, facilitated, and learned from many meetings with security teams. Let's take a look at the challenges that you may face when interacting with them:

The sections that follow will help you articulate how Microsoft Exchange Server is secure, either intrinsically due to the software engineering approach, by the components that are secure by default, or by design.

In 2002, Microsoft implemented the Trustworthy Computing (TwC) initiative. Bill Gates defined Trustworthy Computing as “computing that is as available, reliable, and secure as electricity, water services, and telephony.” Microsoft has invested in and matured their Trustworthy Computing initiative over the last 11 years. Today Microsoft delivers Trustworthy Computing in the following ways:

Microsoft Exchange Server is no exception to this process, and versions as early as Microsoft Exchange Server 2003 were developed in accordance with the Trustworthy Computing initiative. Let's take a look at the impact this initiative has made on Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 by examining what is “Secure by Default.”

The ability to articulate to your security officer how Microsoft Exchange is secure is vital. As messaging consultants, we are often asked by a security officer to explain how Microsoft Exchange Server is made secure. Let's discuss how this question is best answered using the right security language.

It is always best to begin by explaining how Exchange Server is Secure by Default, that is, right out of the box. Table 8.1 provides you with some of the information you will need to explain this to your security officer. Most of these capabilities were introduced during the SDL of Microsoft Exchange and thus were present in early versions of Exchange. For this reason, we focus both on these capabilities and those that were newly introduced in Exchange 2013.

Table 8.1 Security capabilities in Microsoft Exchange 2013

| Capability | Description | New in Exchange 2013 |

| Secure client to server communications | HTTPS to secure communications between clients and servers (Autodiscover, OA, OWA, EWS, OAB, ActiveSync, POP3, and IMAP4). | No |

| POP3 and IMAP4 | Disabled by default. POP3 and IMAP services on the Client Access role and the Mailbox server role are disabled by default. | No |

| Transport security | SMTP uses certificates to encrypt and authenticate the SMTP protocol between Mailbox servers and Edge servers and partner organizations. By default, Exchange 2013 servers will always attempt to communicate via TLS but will automatically fail over to unsecure SMTP if the destination server does not support TLS. | No |

| Secure Edge synchronization | Edge synchronization process: Encryption of LDAP traffic between Edge servers and Exchange 2013 Mailbox servers. | No |

| Native antimalware functionality | By default, malware filtering is enabled in Microsoft Exchange Server 2013. The default antimalware policy controls your company-wide malware filtering settings. | Yes |

| Role-based setup | Ensures that only the intended roles and services are installed on the target server by performing a server hardening by default. Limits communication to the ports required for the installed services and processes running on each server role. | Yes |

| Administrator access to users' mailboxes | Since Microsoft Exchange Version 5.5, administrators with Full Exchange privileges do not, by default, have access to every mailbox within the organization. An administrator who has Full Exchange privileges can grant herself rights to a specific mailbox. | No |

| Exchange services—local authority | Exchange services no longer run under a single server account to which administrators (and others) used to know the password. Exchange services run under the local system or the network service security context. | No |

| RBAC | Introduction of RBAC in Microsoft Exchange 2010 provided the ability for a more granular-level assignment of permissions to users and groups. It is now possible to adhere to a least-privilege principle. | No |

| Always up-to-date setup | When the setup utility is run, the user is given the option to download and use the latest rollups and security hot fixes. The setup executable itself is updated. | Yes |

| Auditing reports | From within the EAC, you can run reports or export entries from the mailbox audit log and the administrator audit log. The mailbox audit log records whenever someone other than the person who owns the mailbox accesses a mailbox. This can help you determine who has accessed a mailbox and what they have done. The following reports are now available within the EAC:

|

Yes |

| Transport rules | Enhancements have been made to transport rules. New predicates, such as AttachmentHasExecutableContent, MessageContainsDataClassifications, SenderIPRanges, GenerateIncidentReport, ReportSeverityLevel, and RouteMessageOutboundRequireTLS, provide the administrator with more flexibility and control when implementing data loss prevention rules. | Yes |

| Information Rights Management (IRM) | IRM provides the ability to control what a user can do with a message. IRM is now compatible with Cryptographic Mode 2, an Active Directory Rights Management Services (AD RMS) cryptography mode that supports stronger encryption by allowing you to use 2048-bit keys for RSA and 256-bit keys for SHA-1. Additionally, Mode 2 enables you to use the SHA-2 hashing algorithm. | Yes |

| Message throttling | The ability of the administrator to set a group of limits on the number of messages and connections that can be processed by the Exchange 2013 server. These limits can prevent unintentional exhaustion of system resources. For example, they could be used to prevent a mass-mailing worm. | No |

In software engineering terms, Secure by Design means that the software has been designed from the ground up to be secure. You are now able to articulate the process that Microsoft uses and the capabilities that are provided to ensure that Microsoft Exchange Server is secure by default. In infrastructure design terms, when the term Secure by Design is applied, it refers to how the environment has been made secure throughout the design phase.

How secure you make the environment depends on the security requirements that you gather from the security officer, and those requirements should accurately reflect and address the probability of threat, the impact should the system be compromised, and the overall risk to the organization.

As messaging consultants, you have an extremely important task to accomplish in helping to define the security requirements of the Microsoft Exchange Server estate. Quite often, it is your role to understand the generic security requirements (for example, all Exchange data, databases, and logs must be encrypted). You must then translate these into the components that must be implemented and configured (for example, all Exchange servers must be encrypted using Microsoft BitLocker). When the security requirements are well defined, the translation process is relatively straightforward, but as you will learn in the next section, these requirements can often be quite ambiguous.

How do you build a security policy for your business, and what is a sensible starting point? Start by simply asking your security officer this question: “What are the existing corporate security policies, and how are they implemented today?” The response to this question largely depends on the type of customer. Some customers know they should have security but don't know a lot more. A customer who still believes in all of the old best practices when securing Exchange is likely to take the belt-and-braces approach, that is, to secure everything possible, because it is too complicated to try to understand the business requirements and the functionality to meet those requirements. Finally, those clients who have strict security policies in place for a good reason, such as organizations that handle classified information, may respond, “Where should we start?”

One of the most important approaches within infrastructure architecture is not to assume but to reason. While it is important to understand how security is implemented within the current system, do not assume that it is a true reflection of the real requirement; for the majority of customers, this will not be the case. Frequently, the required security policies are not implemented because of a lack of functionality or capability within the product, a lack of investment, or simply that the functionality is too complex both to implement and support.

Frequently, the difference between a must and a should requirement is a tradeoff between the risk, the investment required to implement, and the complexity and maintainability of the solution within the production environment. For that reason, it is vital that when requirements are being defined, you can articulate the cost, complexity, and supportability of the functionality required to meet the requirement.

One challenge remains when defining the security requirements for the solution; that is, how do you deal with customers who know they should have security but don't know a lot beyond that? These are customers and security officers who are not able to provide you with their requirements; consequently, your job is then to tease the requirements out of them. For those customers, we find that a list of questions is helpful. Table 8.2 provides a good starting point.

Table 8.2 Questions for defining security requirements

| Question | Consideration and Solution |

| Do you have any requirements for the encryption of data at rest? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

Exchange 2013 alone cannot encrypt Exchange data. However, Windows BitLocker can be used to encrypt Exchange data stored on the Exchange servers. |

| Do you have any requirements for the encryption of data in transit? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

Client to server traffic is secure by default. Are there any requirements to secure SMTP traffic (i.e., to use TLS)? Is there a requirement for end-to-end encryption of message data (i.e., the use of S/MIME and/or cloud based to encrypt messages)? |

| Do you have any requirements for the encryption of data in long-term storage? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

How are tape backups to be secured? (Does the backup solution encrypt the data on tape?). Who has access? Are backup tapes kept off-site? |

| Do you have any requirement that users apply digital signatures to emails so that the recipient can verify the validity of the sender? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

AD RMS required. |

| Do you have requirements for enabling users to protect email content with Information Rights Management controls?

Is there a requirement to prevent users from copying/forwarding/printing emails? |

Protect against unauthorized data access.

AD RMS required. |

| Are there any firewalls in between sites and servers or clients of which this solution should be aware? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

May affect supportability of Exchange 2013, depending on the implemented firewall rules. |

| Do you have the ability to use an internal PKI? Where external certificates are required, do you have a preferred third-party supplier? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

Securing client to server traffic. |

| Do you have a requirement to classify data? Is there data in the environment that if leaked would cause a significant impact on the organization? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

Common in government agencies. Often these types of organizations have a requirement to classify data on levels of impact. Hub transport rules can be implemented to recognize and classify data. |

| Is there a requirement to implement address book segmentation so that some users do not have permission to view other users within the address book? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

Address book policies required. |

| Is there a requirement to provide two-factor authentication for external access methods? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

Applicable to Exchange ActiveSync, Outlook Web App, and Outlook Anywhere. Client certificates, IPSec, VPN, DirectAccess, soft/hard security tokens. |

| Can wildcard certificates be used? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

Wildcard certificates can make configuration simpler, but have some constraints in usage. In addition, by security policy, some organisations will not allow the use of wildcard certificates. |

| Is there a requirement to implement a least-privilege, granular-permissions model for system administrators? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

The Active Directory administrative model should follow the least-privilege model to ensure that only the required privileges for a specific job role are granted. |

| Is there a requirement for system administrators to have separate user accounts and administrator-level accounts? | Protect against unauthorized network access.

These accounts should always be separate and not be shared by a group of users. |

| Must the solution include the ability to log authorized and unauthorized access to users' mailboxes? | Protect against unauthorized data access.

Enable Mailbox Auditing |

| Must the email system provide the capability to scan internal emails (that is, messages sent and received between internal users) for spam and malware? | Protect against malware and spam.

Enable antimalware and antispam agents on Mailbox servers. |

Now that you have a defined set of requirements, adequately categorized in the appropriate manner, let's take a look at how to meet these requirements using native operating system or Microsoft Exchange 2013 functionality, through the use of third-party software, or through a combination of all three.

Given that the security officer is likely to articulate requirements against the perceived threats, this section of the chapter is designed to provide you with an understanding of the capabilities that can be implemented to secure the solution and mitigate those specific threats. For example, how to protect the environment from spear-phishing attacks (discussed previously in this chapter) is covered in the section “Protecting against Malware and Spam” that follows. Implementing functionality to protect against unauthorized network access, for example, securely publishing Exchange using reverse proxy solutions, is covered in the “Protecting against Unauthorized Network Access” section, and so on.

Typically, an organization will require protection against malware and spam using a multilayer defense barrier. Within the industry, this is commonly referred to as defense in depth. In addition to this security principle, organizations may wish to ensure that the different layers cover a broad spectrum of products, vendors, and suppliers. For example, an organization that subscribes to Symantec Cloud Services to provide malware and spam protection will then not implement Symantec Mail Security for Microsoft Exchange 2013, Symantec Endpoint Protection for Windows 2012, and Symantec Endpoint Protection for their client base.

Following is a brief overview of different layers of message protection and offerings:

In addition to application-level protection, it is advisable that the operating system and the files on a Microsoft Exchange server be protected from malicious code. This is commonly known as file-level protection. However, it is vital to make sure that the appropriate Exchange file and directory-level exclusions are in place to avoid issues with Exchange Server 2013. Refer to the following TechNet article for additional information:

http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb332342.aspx

Let's take a closer look at the Microsoft offerings and the built-in functionality now included within Exchange 2013 for each of the layers defined here.

Exchange Online Protection (EOP) is the replacement for the recently retired Forefront Online Protection for Exchange (FOPE), Microsoft's hosted email gateway. EOP provides comprehensive email protection (through multiengine antivirus) and continuously evolving antispam protection. It also boasts enterprise-class reliability, flexible policy rules, and a streamlined administration console with detailed reporting.

Some major improvements have been made to this latest version of EOP, including the use of an integrated console, common policy rules (built on the same stack as the Exchange transport rules), and some spam-handling improvements. EOP performs both inbound and outbound filtering.

Microsoft's recommended guidance for Exchange Server 2013 security is to use EOP alongside the Exchange Server 2013 built-in antimalware and antispam features, removing the management and administration overhead of the Edge Transport server role.

Deploying EOP involves the following four, high level activities:

If you wish to set up rules based on users/groups or user attributes within Active Directory, or if you want to synchronize safe/blocked senders lists, you will also need to set up and run Directory Synchronization, which takes advantage of the Office 365 DirSync process.

EOP uses several methods to block spam. Connection filtering is the first line of defense that blocks spam at a TCP layer. EOP uses the Spamhaus and internal databases to block connections from known spammers. (Spamhaus is an international organization that tracks email spammers and spam-related activity.) Eighty percent of spam is captured at this layer. EOP will automatically add those sending over 90 percent spam to the internal block list. However, you cannot rely on this method alone, because spammers now send only five to nine messages from one IP address.

The second layer is sender-recipient filtering, which is reported to block up to 15 percent of all spam based on internal lists and sender reputation. When the EOP servers receive the HELO (or EHLO) command, the sending host/service name is checked against a list of banned hosts.

The third layer is content filtering, which blocks the final 5 percent of all spam based on the internal lists and heuristics. Included within the content filter is the capability of blocking certain URLs within emails. This protects against phishing attacks and, more significantly, the spear-phishing attacks discussed earlier in the chapter. A geographically distributed Microsoft team exists entirely to watch mail streams, keep all of these lists and rules in check, and work out new content rules.

EOP also offers good protection against spoofing, which is an email message with a sending address modified to appear as if it originates from a sender other than the actual sender of the message. To accomplish this, EOP utilizes sender policy framework (SPF) and sender ID filtering. SPF records, once implemented on external DNS zones, identify authorized outbound email servers. Unlike FOPE, EOP provides granular options for the detection and management of spam, including the ability to block bulk mail and block email based on a language and/or geography.

Multiple engines facilitate antimalware capabilities within EOP. Other enhancements over FOPE include the introduction of a new action to remove unsafe attachments but still deliver the message content. Once detected, EOP can send a notification message to the sender of the undelivered message and to a system administrator. This capability can be enabled/disabled for internal/external users separately.

EOP also provides the ability to configure customized mail rules. This capability is built upon the Exchange transport rules engine. Rules are comprised of conditions used to identify specific criteria such as sender, receiver, and keywords within a message, actions that are applied to email messages that match the conditions, and exceptions that identify messages to which a transport rule action should not be applied. In addition to the functionality provided in Exchange Server 2010, both EOP and the on-premises version of Exchange 2013 allow rules to be run between certain dates and to run in a test mode, with or without notifications. Having the ability to run transport rules in a test mode with notifications is ideal when configuring rules within EOP to block messages, because it allows you to test rules before inadvertently blocking critical messages.

Most importantly, to help the security officer assess the probability of a threat, EOP provides built-in granular reporting options that present a clear view on spam filtering and malware attacks. One constraint to bear in mind, however, is that only 60 days of summary data and 7 days of detailed data are provided.

Finally, EOP provides a streamlined management console, as shown in Figure 8.1, for control over the settings for antispam and antimalware, RBAC, domain management, message tracing, and quarantine management. If you have an Exchange Enterprise Client Access License (ECAL) with services or you are an Office 365 customer, you will also have the ability to connect to EOP through PowerShell.

Figure 8.1 EOP streamlined management console

To act as an ingress and egress point for Internet email, the Edge Transport server must be deployed into the organization's perimeter network. Given that the Edge Transport server is not installed on the internal network, for most organizations this means that the server is not joined to a domain. However, larger enterprises sometimes have domain(s) dedicated to the perimeter and, in that scenario, Microsoft will support the Edge Transport server being joined to a domain. When the Edge Transport server is not domain-joined, configuration and recipient information that the Edge Transport server requires is stored in Active Directory Lightweight Directory Services (AD LDS). Internal Active Directory information can be synchronized (commonly known as EdgeSync) to the Edge Transport server by subscribing the Edge Transport server to an Active Directory site. This associates the Edge Transport server with the Exchange organization. Once established, the EdgeSync process enhances antispam features by providing the capability to perform recipient lookups and safelist aggregation, which refers to the ability to collect data from the user's safe/blocked senders list in Outlook. Once the data is collected, the Edge Transport server can use it to reduce the number of false positives. The EdgeSync process also provides the ability to secure SMTP communications with partner domains using mutual transport layer security.

The Exchange 2013 version of the Edge Transport role was not shipped when Exchange 2013 reached general availability in early December 2012. Therefore, it is possible to coexist (and even deploy) Exchange 2010 Edge Transport servers with Exchange 2013 servers. Additional information about the Edge Transport server role is available at the following TechNet address:

http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb124701(v=exchg.141).aspx

It is important to be aware of some essential considerations if you plan to use Exchange 2010 Edge Transport server to protect your Exchange 2013 infrastructure. These considerations are as follows:

Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 is the first release of this product to provide basic, built-in antimalware protection. In previous versions, if you required Exchange-level protection for Exchange, you either deployed Forefront Protection for Exchange (FPE) or a third-party product such as Trend Micro's ScanMail. Historically, Exchange administrators have experienced many instability issues with third-party products using the Virus Scanning API (VSAPI) to provide antimalware and antispam functionality. Microsoft has elected to build in protection for their products as native functionality, rather than having an extra, third-party layer on top. This doesn't mean, however, that a third-party product cannot be used instead of the built-in functionality.

By default, malware filtering is enabled and the antispam agents are disabled on the Exchange 2013 Mailbox server role. It is recommended that you enable the antispam agents on the Mailbox server role if your organization has not deployed an Edge Transport server role in the perimeter network. The Exchange 2013 antispam agents that run on the Exchange 2013 Mailbox server role are installed and enabled by default on the Edge Transport server.

The following list defines the antispam agents and, should they be enabled, the order in which they are applied to the message in transit on the Exchange 2013 Mailbox server:

The following agents, available on the Edge Transport server, are not available on the Exchange 2013 Mailbox server role. Should there be a requirement for you to deploy either of these two antispam agents, you will need to deploy an Edge Transport server.

Although they are disabled by default, the antispam agents maybe enabled on the Exchange 2013 Mailbox role with the following command:

& $env:ExchangeInstallPath\Scripts\Install-AntiSpamAgents.ps1

Once this command is run, you must restart the Microsoft Exchange Transport service on the Mailbox server.

Because malware scanning is enabled by default on all Mailbox servers, messages are scanned for malware when sent to, or received from, a Mailbox server. EAC can be used to configure your default, organization-wide malware filter policy. To be able to configure any of the antispam and antimalware functionality within Exchange Server 2013, you must be a member of either the Organization Management or Hygiene Management RBAC role group.

EAC provides simple management of the default malware policy, which can be found under the Protection menu item. EAC provides the ability to choose how you wish email to be treated should malicious code be detected. Options are provided to delete the entire message or to delete all attachments and replace with either default or custom text. The administrator also has the option to send customizable notifications to both the sender and the system administrator. You can also differentiate between internal and external senders.

EAC blocks the ability to create new malware filters, but the following shell command is available to do this:

New-MalwareFilterPolicy –Name <Name>

Although you may be able to create new malware filter policies from PowerShell, you will be unable to scope the policy (which renders making new policies useless). Within EAC, the default policy is shown as being Scoped To: All Domains. From this, you can take some comfort in knowing that Microsoft does have plans to enable the scoping of malware filter policies in future releases.

By default, Exchange 2013 will check for new malware engines every hour. Doing so requires an Internet connection. Engine updates can also be invoked manually from an Exchange server that has Internet connectivity by running the following script:

& $env:ExchangeInstallPath\Scripts\Update-MalwareFilteringServer.ps1 -Identity <FQDN of server>

Currently there is no published guidance on how to download an engine update from a non-Exchange server. This procedure is required if your Exchange 2013 servers are not configured to connect to the Internet, but it is anticipated that the procedure will be the same as it was for updating the scan engines in Microsoft Forefront Protection for Exchange (except for a code change to download only one engine). This procedure is defined in following support article:

http://support.microsoft.com/kb/2292741

There are two options available to stop messages from being scanned by the antimalware filter on a Mailbox server. The first action is to disable the filter. Malware scanning should be disabled if you opt to run a third-party product (for example, Trend ScanMail) as a replacement for the native functionality. If you disable the malware scanning, the agent will stop and no further engine updates will be performed. The following script can be run to disable the malware filter:

& $env:ExchangeInstallPath\Scripts\Disable-Antimalwarescanning.ps1

Once this script has been run, you will be prompted to restart the Exchange Transport service. Should you wish to re-enable the agent, it will perform an engine update when the following script to enable it is run:

& $env:ExchangeInstallPath\Scripts\Enable-Antimalwarescanning.ps1

To unhook the antimalware agent temporarily for troubleshooting purposes, it is recommended that you implement a bypass. Although the agent is then bypassed, the engine is kept up to date. You can bypass the antimalware agent with the following command:

Set-MalwareFilteringServer -BypassFiltering $true

You can re-enable it using the $False parameter. Note that this command does not require you to restart the Exchange Transport service, causing no disruption to mail flow.

To ensure that you understand whether the built-in antispam and antimalware capabilities will meet your requirements, here is a summary of the constraints present within the initial release of Microsoft Exchange Server 2013:

It will soon be common for email users to access their corporate email solution mainly from a device that is not connected to their corporate network. With the majority of users accessing an email infrastructure externally, securing that access and the infrastructure that is used to permit that access becomes critical. In this section, we examine the options to make Exchange services securely available externally and how to secure communications between devices and the Exchange environment.

It has been possible to provide external browser-based access to Microsoft Exchange since version 5.5, although most organizations were not faced with strong demand until Exchange 2003 was released. At that point, the demand for providing external connectivity to Outlook Web Access grew. Since then, organizations have become savvier with their externalization strategy, investing heavily in network perimeter zones to ensure that network access to all enterprise infrastructure is secured by an additional network layer between the untrusted Internet and the organization's local area network. When working with a wide range of clients, we always find it refreshing to learn of new names for perimeter networks, from Secure the Perimeter (STP) to the Purple Zone. While perimeter zones provide a single location whereby external access can be simply managed, secured, and monitored, in so doing, organizations ultimately provide a single point of attack for potential hackers. For this reason, many large organizations, with Microsoft being no exception, are currently reconsidering their strategies for providing external access.

Historically, Microsoft promoted the use of an Internet Security and Acceleration (ISA) server to publish Microsoft Exchange services securely to the Internet using a variety of designs. Some of these designs included Exchange front-end servers to be placed in the perimeter zones along with the publishing server. Since Exchange 2007, installation of a Client Access server in a perimeter network zone has not been supported, relying heavily on the publishing server, and more recently Forefront Threat Management Gateway (TMG) 2010, to secure communications to the internal Microsoft Exchange infrastructure.

In September 2012, Microsoft announced that no further development will take place on Forefront TMG and that the product will no longer be available for purchase as of December 2012. Mainstream support will end for Forefront TMG on April 14, 2015, and extended support will end on April 14, 2020. Once mainstream support has ended, Microsoft will not provide any non-security hotfix support (unless an extended hotfix agreement has been purchased), offer any design changes, or honor any feature requests, and they will not provide any no-charge incident support or service any warranty claims.

Should you wish to use a Microsoft product to secure external access to Microsoft Exchange 2013 by performing pre-authentication, what are your options? Forefront Unified Access Gateway (UAG) 2010 will be the only publishing option available to purchase from Microsoft going forward, although Forefront TMG server will continue to work with Exchange 2013 and be supported until April 2015. For the initial release of Exchange Server 2013, Microsoft did not recommend using UAG to publish Exchange 2013 services. This is due to the incompatibility of the Outlook Web App and the deep URL inspection that UAG performs. However, this was recently resolved in the Service Pack 3 release for UAG 2010.

If you plan to use Forefront TMG 2010 to publish Exchange 2013 services securely to the Internet, it is important that you follow the publishing guidance provided for Exchange 2010. There are some important amendments to this guidance, however, that need to be addressed to make this work:

More information about publishing Exchange Server 2013 using TMG can be found here:

If your organization has already bought the required TMG licenses, you are able to continue to deploy and use TMG 2010 to publish Exchange 2013 services. It is vital to ensure that your company has a roadmap to move away from TMG within the next three to five years. Be mindful that licenses can no longer be purchased, so before you steam ahead and deploy into production, check to be sure that you have all the licenses that you will need. If your organization is new to publishing Exchange services and wishes to publish Exchange 2013 services to the Internet, and if you have not yet purchased Forefront TMG licenses, your best option is to purchase and deploy Forefront UAG 2010.

It is likely that more publishing options will become available from other vendors as Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 matures. If your organization has a strong Defense in Depth security strategy, it is likely that you will have a requirement that prohibits you from using Microsoft's Forefront TMG or UAG products within the perimeter network.

It is important that the requirements drive the adoption and deployment of a reverse proxy solution, and that it isn't simply assumed that one is required. Many enterprises, including some of the largest, publish Client Access servers directly to the Internet; that is, they do not use TMG, UAG, or a third-party product. If preauthentication is not required, then a hardware load balancer can be deployed at the network edge (the device must support this deployment scenario) to accept HTTPS traffic and to forward that traffic directly to the Client Access server.

By default, all communications between the client (be it Outlook Anywhere, Outlook Web App (OWA), or ActiveSync) and Exchange 2013 are secured by using Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). Exchange 2013 requires the use of digital certificates installed on the servers themselves to create the SSL-encrypted channel that is used for client communications. So even though you have the ability to encrypt data communications between the client and the server, your security officer will remind you that it doesn't help if your identity has been stolen and someone has logged onto OWA with your password. As you learned at the beginning of this chapter, about 40 percent of those surveyed were concerned about the threat posed by remote and mobile working. Thus it is quite possible that your security officer will require the ability for remote access not only to be encrypted but also to be secured by a second factor.

Two-factor authentication is an authentication principle that requires the presentation of two or more factors: a knowledge factor (something the user knows) and a possession factor (something the user has). In principle, two-factor authentication decreases the probability that the requester is presenting false evidence of its identity. The ability of a solution to provide a second form of authentication is increasingly becoming a requirement because of the ease at which passwords can be compromised, mainly through nontechnical methods such as coercion, user profiling (which involves hackers guessing passwords based on information disclosed on social network sites), bribery, and users simply writing them down. Finally, it is possible for a savvy hacker to make a mental note of a user's password by watching the user type in their password on a keyboard in a public location.

What are your options with Exchange 2013 when faced with a requirement to secure external access with two-factor authentication? Client certificates can be used to prove the identity of the connecting user, and the “something the user has” criterion for two-factor authentication is then met with the client certificate. If your security officer accepts this as a valid second factor, then the security of that client certificate must also be addressed as part of the solution, for example, by certifying how the certificate is securely stored on the device.

If you use Forefront TMG to publish Exchange, support for certificate-based authentication was built into Cumulative Update (CU) 1 for Microsoft Exchange 2013. The initial release of Exchange 2013 could not use certificate-based authentication because of a lack of support for Kerberos Constrained Delegation. There are two important considerations for certificate-based authentication: First, it is the only supported method (without using additional software and/or services, such as PhoneFactor) to provide two-factor authentication for ActiveSync and mobile devices. Second, Outlook Anywhere does not support the use of certificate-based authentication (using any Outlook version). Certificate-based authentication can also be used with OWA, when the Forefront UAG server publishes OWA. More information on how to configure Forefront TMG with certificate-based authentication for OWA and EAS and Forefront UAG for OWA can be found in the following white paper:

http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=302

Configuring IPSec on the endpoint that is used to publish Exchange to the Internet has previously been recommended for use with Exchange 2010. IPSec does not require any significant investment in infrastructure, and it can be provisioned easily. In addition, both Forefront TMG and Forefront UAG work well with an IPSec-based security solution. More appropriately, it can also be used to secure authentication for Exchange 2013. (The reality is that Exchange neither knows nor cares about it.)

Given that any connection attempt made to the endpoint must first succeed at the IPSec negotiation layer (rather than just the username/password layer), configuring IPSec is a way to provide the second factor and thus reduce the possibility of a denial-of-service (DoS) attack. When IPSec is enabled on either the Forefront UAG server or the TMG server, only clients with the proper credentials can establish a connection, and both computers need to agree to communicate with each other before application access is permitted. IPSec can be used to secure OWA, OA, EWS, and Autodiscover. It is generally not used for EAS, since it is not natively supported on mobile devices. A quick overview of the requirements and configuration process for IPSec follows:

Although IPSec is a cost-effective way of providing two-factor authentication, it is sometimes perceived as a difficult solution to manage and maintain. This is largely due to two limitations: First, the configured IPSec policies on the clients contain IP addresses and not the DNS addresses of the connection endpoint(s). Therefore, should an IP address change, the IPSec polices must be updated. (This is the reason why IPSec policies must be configured as part of a GPO, so that it is possible to update them centrally and distribute them automatically to all client machines.) Second, the use of IPSec is known to place a processing overhead on network cards (although this is understood to be less than that required for SSL). However, the advantages of using IPSec with Exchange 2013, in that both Outlook Anywhere and OWA support it as a two-factor authentication solution, and that it does not require the use of third-party software, outweigh its limitations.

Unquestionably, establishing a VPN connection before using Outlook Anywhere or OWA facilitates the use of two-factor authentication. However, this authentication process is not transparent to the user, and with the growth of working remotely, the process of having to establish a VPN connection is perceived by users as unnecessary overhead. Similar to VPN, DirectAccess (Microsoft's solution for providing users seamless access to their corporate infrastructure from virtually any Internet connection) also facilitates two-factor authentication with the advantage that the connection and authentication process is transparent to the user. However, the limitations to and solution requirements for DirectAccess are not trivial: They are Windows 7 Ultimate/Enterprise or Windows 8 (if DirectAccess with Windows Server 2012 is used) domain-joined clients and Forefront UAG as the preferred edge solution.

Thus far, all of the two-factor authentication access methods considered require that software, policies, and/or certificates be specifically installed or configured on the client. What are your options if you have a requirement to provide two-factor authentication for OWA when being used in a kiosk scenario? In this case, when the asset is not owned by the organization, and the organization is not in control of the client machine (for example, a computer in an airport), you do not have the luxury of being able to install any additional software and/or updates. Third-party products have been available for Exchange 2010 to secure and provide two-factor authentication for OWA by integrating with IIS and requiring the use of either a hardware or software token (for example, a one-time secret code or one-time password). Through its recent acquisition of PhoneFactor, Microsoft now owns a native solution with the ability to secure OWA via the two-step verification process. Other third parties such as Swivel (Office 365 solutions), ArrayShield, and Duo Security are all examples of companies that provide two-factor authentication solutions for OWA. At the time of this writing, however, none have updated their products to work with OWA 2013.

PhoneFactor leverages the user's mobile device as the “something you have” trust factor. A PhoneFactor agent runs within the corporate network, intercepts the OWA SSL requests, and sends them to the cloud-based PhoneFactor service. A phone call, text message, or a notification is then sent from the PhoneFactor cloud-based service to the user's mobile device. Once the user approves or denies the access request from their mobile device, it returns the access result to OWA. In contrast, Messageware provides the functionality to filter OWA logons by IP address or location, an OWA CATCHA challenge, and other functionality (such as secure email attachment viewing, navigation, and session protection) to secure OWA 2013 logons and sessions.

Two-factor authentication for OA using smart cards (as discussed in the following TechNet article) is not supported in the current release of Microsoft Exchange Server 2013, although it is expected to be supported in future releases:

http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/hh227263(EXCHG.141).aspx

For those of you who may be wondering about claims-based authentication (AD FS) support in Exchange 2013, or perhaps even managed to make it work, Microsoft does not support OWA or OA using claims-based authentication. Thus it is not something that you should recommend as a two-factor solution to the security officer.

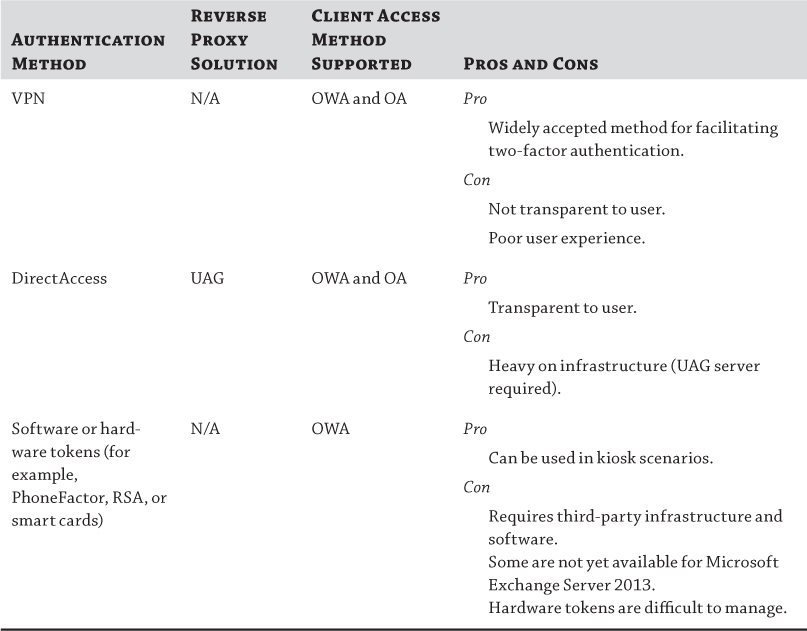

Table 8.3 summarizes the available methods for two-factor authentication with Microsoft Exchange Server 2013.

Table 8.3 Two-factor authentication methods for Microsoft Exchange Server 2013

In this section, we examine some of the common concerns that may require attention to ensure that corporate messaging data is secured in such a way as to protect against unauthorized data access. To understand fully the range of concerns within this area, it is paramount to appreciate the potential threat.

This section is divided into three parts:

Ensuring that messages are securely transferred to their destination is a fundamental requirement and thus the functionality that facilitates this is expected. Microsoft Exchange Server 2013 provides a variety of options to facilitate the secure exchange of messages. Nonetheless, it is important to understand the default behavior and whether this meets the defined requirement(s).

For messages that are transferred within the Exchange organization, all mail flow between Exchange 2013 servers is secured by Transport Layer Security (TLS). By default upon install, all Exchange 2013 servers are configured with a self-signed certificate that facilitates this TLS encryption of SMTP traffic. TLS encryption is mandatory for all SMTP communications between Mailbox servers.

In addition, messages that are accepted for delivery by the Front End Transport service into the Exchange 2013 organization are streamed (because there is no SMTP queuing functionality on the Front End Transport service) to the relevant delivery group via TLS. Furthermore, all traffic between Edge Transport servers and Exchange 2013 Mailbox servers is both authenticated and encrypted.

For messages that are being sent externally from within the Exchange organization, whether these are routed through the Client Access server or straight to an Edge server, Exchange 2013 will always attempt delivery to the remote SMTP server via opportunistic TLS. By default, Exchange Server 2013 will always try to negotiate TLS by issuing the StartTLS command during the initial SMTP conversation exchanges. Interestingly, even if the self-signed certificate has expired, opportunistic TLS will still work as long as the target server accepts the StartTLS command. To that end, it is important to understand that, by default, a significant proportion of outgoing mail will be encrypted via opportunistic TLS without the need for any further configuration.

Is opportunistic TLS sufficient to meet your requirements? There are two distinct factors that will help you determine this based on the requirements that have been defined. It is vital to understand that opportunistic TLS will only encrypt the communication session, and that it will do so only if both the sending and receiving server can negotiate a TLS session. If there is a requirement to ensure that encryption is enforced to a particular domain/partner, or that the SMTP traffic must be both encrypted and authenticated (that is, that the sending and receiving server validate their authenticity), then mutual TLS must be configured. From experience, the requirement to enable Domain Security, which describes the functional components (that is, the certificates, connector configuration, and Outlook functionality that enables mutual TLS), is most commonly driven by the requirement of organizations to communicate securely with a third-party vendor, service provider, or outsource agency. A simple example is a retail company with the requirement to send all email via an encrypted and authenticated session to their bank, such as retailbankprovider.com.

Should you be faced with the requirement to enable Domain Security, the following steps provide a high-level overview on how this must be performed:

Set-TransportConfig –TLSSendDomainSecureList "retailbankprovider.com"

Set-TransportConfig –TLSReceiveDomainSecureList " retailbankprovider.com "

If you are planning to implement Domain Security, there is one final consideration: Domain Security isn't supported when outbound email is routed through an Exchange 2013 Client Access server. The FrontendProxyEnabled parameter on the Set-SendConnector cmdlet is used to configure whether outbound email is routed through the Client Access server. By default, outbound mail is not routed through the Exchange 2013 Client Access server.

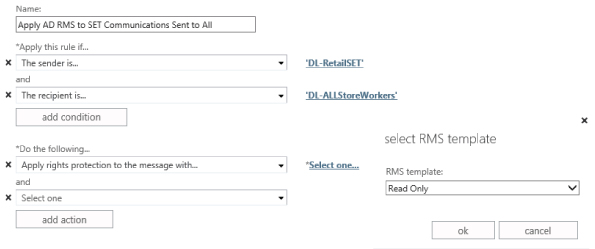

New to Exchange Server 2013 is the ability to set a transport rule to enforce TLS encryption. This is achieved by the new transport rule action, RouteMessageOutboundRequireTLS. This new action enforces the use of TLS encryption when routing messages externally. If TLS encryption isn't supported, the message is rejected and not delivered. Figure 8.2 shows a sample transport rule being created to meet a requirement that when all members of the Retail group's Senior Executive Team (SET) send emails to retailbankprovider.com, TLS encryption is applied. Should TLS encryption not be possible, the message will then be rejected. In this example, Domain Security is not configured for the stipulated recipient domain. Thus, TLS encryption will not be enforced for users who are not members of the RetailSETMembers group.

Figure 8.2 Configuring transport rules to set up TLS

One final concern may remain in the security of data in transit, and that is the security of database availability group (DAG) replication traffic. Given that DAG replication is now supported over wide area networks, it is possible that DAG data may be replicated over unsecured WAN links. By default, network encryption is only used on DAG networks when replicating across different subnets. Network encryption utilizes Kerberos security to provide authentication between Exchange servers. Should there be a requirement for a more stringent level of encryption on the DAG network, the Set-DatabaseAvailabilityGroup cmdlet can be used to configure the encryption settings. Possible encryption settings for DAG network communications are listed in Table 8.4.

Table 8.4 Possible encryption settings for DAG network communications

| Setting | Description |

| Disabled | No network encryption is used. |

| Enabled | Network encryption is used on all DAG networks for replicating and seeding. |

| InterSubnetOnly | Default setting. Network encryption is used on DAG networks when replicating across different subnets. |

| SeedOnly | Network encryption is used on all DAG networks for seeding only. |

To prevent data at rest from being accessed, stolen, or altered by unauthorized persons, some organizations will consider the application of encryption or Information Rights Management on messaging data. Whether data is at rest on Exchange servers, workstations, laptops, or mobile devices, the risk of unauthorized data access will vary, generally depending on the portability of the device. However, the impact on the organization of unauthorized data access could be considerable and could cost millions.

Let's initially consider the risk of unauthorized data access to the messaging data stored on a Microsoft Exchange server. Historically, prior to the centralization of messaging services, Exchange servers may have resided in remote and unsecured areas. However, by today's standards and because of the trend toward centralization, it is common for Exchange servers to be secured within corporate datacenters. Therefore, the risk of unauthorized physical access is reduced. That being said, the risk is still there.

What happens when an engineer walks off-site with a disk (especially a disk that has been part of a JBOD configuration), which may store a complete copy of an Exchange database? Should that data be unsecured, a corporation will be at the peril of an untrustworthy (and perhaps external) engineer. In addition, once the data is removed from the site, how can you guarantee its security? Even if the disk has a flaw, this alone will not render the data inaccessible. There are native tools and many third-party utilities that can access data within an Exchange database .edb file, removing the requirement for having to perform a complete restore. Given such concerns, you may be faced with a requirement to encrypt data that is at rest (that is, the Exchange databases) on the Exchange servers. If so, what are your options?

By default, data that is at rest on an Exchange 2013 server is not encrypted. Unlike Lotus Notes, Exchange does not provide any native, application-layer functionality to encrypt the mailbox databases. However, BitLocker, a full disk-encryption feature that is included in Windows Server 2008 and Windows Server 2012, is supported for use with Exchange Server 2013 and specifically on volumes that hold Exchange data. At present, it is the only disk-encryption software that is supported for use with Exchange Server 2013. If you plan to use BitLocker to encrypt the data stored on the Exchange server, you should be aware of the following considerations and recommendations:

To enable BitLocker on Windows Server 2012, the feature must be installed from Server Manager. Once installation is complete, a reboot will be required. It is recommended that BitLocker be installed before the node is joined to a DAG. Once the data is encrypted, BitLocker is known to have a slight performance impact on the server—a 1–3 percent CPU overhead. The IOPS performance impact on an Exchange server with BitLocker enabled is reported to be insignificant.

The risk of unauthorized access of data stored on portable devices is today a significant concern to organizations, largely due to the growth of mobile devices and the increased security risk they bring. Organizations are not only concerned with sensitive corporate data being leaked from emails, but they are worried about data such as user personally identifiable information, address book data (stored in the Outlook offline address book), and the ability of an unauthorized user to view locally stored company IM conversations, which may be stored within an offline copy of the user's mailbox.

To secure data at rest on laptop computers, most organizations have a device encryption policy that often requires the use of disk encryption software such as BitLocker. On client machines, Microsoft BitLocker can be used alongside Windows 7 and Windows 8. Once BitLocker is enabled on a laptop computer, encrypting the entire Windows operating system volume on the hard disk, including the Outlook data files such as the Offline store (*.ost), personal address book (.pab), and offline address book (*.oab), will prevent unauthorized access should the laptop be stolen. In addition, BitLocker will encrypt additional data volumes on the device and protect against access to the data on the disk should it be removed from the laptop.

Enabling BitLocker on portable Windows devices is the best and most comprehensive solution to prevent against unauthorized data access. In addition to BitLocker, Exchange Information Rights Management may also be used to prevent data leakage from within the Exchange organization. Exchange IRM uses Active Directory Rights Management Service (AD RMS) to apply both encryption and permissions to emails to prevent recipients from taking an action on the email (such as printing, copying, forwarding, and replying). Exchange 2010 SP3 and Exchange Server 2013 now support AD RMS cryptographic mode 2, which supports RSA 2048 for signature and encryption and SHA-256 for signature. This provides the ability to deliver a stronger level of encryption. It is important to understand that although, like S/MIME, AD RMS encrypts email, it also provides the ability to apply Information Rights Management to the email. Once an S/MIME email has been decrypted, there is no control over what the recipient can do with the information contained within the email.

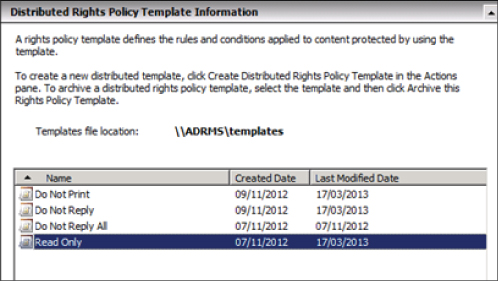

To enable the use of IRM to protect Exchange data, an AD RMS server must be deployed within the Active Directory forest. AD RMS functionality can be added to a Windows 2008 or Windows 2012 server by adding the Active Directory Rights Management Services role. Rights policy templates must then be defined. The rights policy template outlines the rules and conditions applied to the content protected by using the template. AD RMS clients (Windows 7 and Windows 8 are AD RMS clients by default) are then able to request the rights policy templates stored on the AD RMS server/cluster and download and store them locally on the client computer. Figure 8.3 illustrates a sample set of rights policy templates, defined on an AD RMS server, which can be used with Exchange Server 2013 and Microsoft Outlook.

Figure 8.3 Rights policy templates for use with Outlook and Exchange

Predominately, AD RMS is used to encrypt a subset of data that is at rest, for example, one that is based on a user requirement and the user manually applies a template or a template is applied programmatically to a subset of users. AD RMS is not commonly used to encrypt all data at rest, as BitLocker can, because of the administration and performance overhead.

There are three ways to apply IRM (an AD RMS template) to a message:

New-OutlookProtectionRule -Name "Senior Executive Team" -FromDepartment "SET" -ApplyRightsProtectionTemplate "Read Only"

Figure 8.4 Selecting a RMS template in Outlook

Figure 8.5 Creating a hub transport rule in EAC to apply an RMS template

Three predicates are available for use with Outlook protection rules:

To ensure that users accessing their company's email from outside the external network can consume IRM-protected content, the AD RMS server (or cluster) must be published externally. Specifically, there are two URLs that must be published: the licensing URL, which specifies the rights that users have to the content, and the certification URL, which must also be configured on the AD RMS server (or cluster).

Whereas AD RMS provides the capability both to encrypt and rights-protect email content, S/MIME (Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) only provides encryption for email content. S/MIME is sometimes referred to as end-to-end encryption, or writer-to-reader encryption, because messages are encrypted from the initial source (sender or writer) to their target destination (recipient or reader), and the encryption is preserved throughout the message transfer. In addition to encryption, S/MIME also supports the digital signing of a message to provide authentication, non-repudiation, and data integrity. In contrast to AD RMS encryption, S/MIME is based on an industry-standard RFC, and therefore messages can be decrypted and read within a non-Microsoft email client. Both Outlook 2013 and Outlook for Mac 2011 support S/MIME encryption. However, the Exchange 2013 RTM version of OWA does not provide support for S/MIME encryption (although we expect that this support will be added in SP1).

Typically, S/MIME is not widely deployed because of the overhead of maintaining and exchanging user certificates. Both sender and recipient require a certificate (with the recipient requiring a copy of the sender's certificate), which is bound to the sender's validated email address. Old certificates must also be retained, so that historical emails can be decrypted and read. S/MIME certificates can be purchased from a supplier such as Symantec, and most suppliers have an option for a free trial. Once purchased, S/MIME certificates must be renewed, downloaded, and installed once a year. They must also be installed on every device on which the user wishes to send or receive S/MIME messages.

If a certificate is required to decrypt each sender's email, organizations are then unable to decrypt messages to enforce policy compliance or to scan messages for antimalware. For this reason, messages that are encrypted with S/MIME are able to bypass the newly built-in antispam and antimalware capabilities in Exchange Server 2013. In addition, S/MIME encrypted messages cannot be decrypted when performing an eDiscovery search/export, unlike with AD RMS protected content.

Cloud policy-based encryption services, such as Symantec Policy Based Encryption and Exchange Hosted Encryption (EHE), which is part of the Exchange Online Protection offering from Microsoft, can reduce the burden of maintaining individual user certificates across a multitude of devices. With such services, an administrator will stipulate a set of rules (policies) for which messages must be encrypted. Typically, these services will then distribute to the recipient a link to the encrypted mail, where it can be opened from within the cloud encryption service. Within EHE, administrators are able to define encryption policies based on recipient domains, email addresses, message body content (via regular expressions), recipients, IP addresses, and email attachments.

With the increase of Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) strategies, it is now common for users to access their company's email from multiple, and more often than not personal, devices. Even if users do not have this functionality today, the likelihood is that they will expect it, creating a demand that leaves organizations baffled as to how to provide such authorized access without increasing the risk of unauthorized data access. In this final section, we'll examine the options available to secure data at rest on mobile devices.

Windows Phone, Blackberry Enterprise Service, and Good for Enterprise all offer capabilities for the encryption of data stored on mobile devices. Device encryption in Windows Phone 8 utilizes BitLocker technology to encrypt all internal data on the phone with 128-bit Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Encryption is enabled either by an Exchange ActiveSync (EAS) policy or a device management policy. Once enabled, BitLocker conversion automatically begins encrypting the internal storage. The encryption key is protected by the Trusted Platform Module that is bound to UEFI Trusted Boot, in order to ensure that the encryption key will only be released to Trusted Boot components. With both PIN lock and BitLocker enabled, the combination of data encryption and device lock would make it extremely difficult for an attacker to recover sensitive information from a device. Device security settings are managed by native Exchange 2013 ActiveSync policies, which in the main are largely unchanged from previous versions of Exchange Server.

Good for Enterprise provides containerization of the device to create distinct partitions—a personal partition and a corporate partition—on the device (iOS, Windows Phone, or Android) to ensure that data is segmented and, as such, can be managed differently (including the ability to wipe the corporate partition while leaving the personal partition intact). Good uses AES 192-bit encryption on the corporate partition to secure the data. In addition, all data in transit between the device and the enterprise firewall is also encrypted by the same method. The Blackberry Enterprise Service also provides the same containerization through the Blackberry Balance functionality, although it uses a stronger (AES 256-bit) method of encryption. Data transfer between the Blackberry device and the Blackberry Enterprise infrastructure is also encrypted either by AES 256-bit encryption or Triple Data Encryption Standard (Triple DES), depending on how the service is configured. Both the Good and Blackberry Enterprise Service software provide additional functionality for mobile device management, which delivers a more granular level of control than the Exchange Server 2013 native ActiveSync capability.

Since Exchange Server 2010, users have been able to create and view IRM-protected messages on the Windows Phone. Windows Phone is the only smartphone currently available that includes a built-in capability to handle rights-protected email and documents. Apple iOS does not support IRM natively. Devices that support Exchange ActiveSync protocol version 14.1 (Exchange 2010 SP1 and higher), including Windows Phones, can support IRM in Exchange ActiveSync. The device's mobile email application must support the RightsManagementInformation tag defined in Exchange ActiveSync version 14.1 for this to work. It is possible for users of other devices to consume IRM-protected email messages, but a third-party app is required to facilitate this.

iOS devices support S/MIME encryption through the native mail app, while Good for Enterprise can provide S/MIME encryption functionality to Windows and Android phones. (Neither Windows nor Android OS natively supports S/MIME encryption at present.) For Blackberry devices to support S/MIME, the S/MIME Support Package for BlackBerry smartphones is required, and it must be installed on the Blackberry device to enable users to create and view S/MIME-encrypted content. For all devices, use of S/MIME requires the transfer of the S/MIME private key to the device.

Table 8.5 summarizes the options available to secure data on mobile clients.

Table 8.5 Options available to secure data on mobile clients

| Mobile Connection Method | Methods of Encryption Supported | Device Control |

| Windows Phone | Data at rest encrypted by BitLocker.

IRM. S/MIME: Requires third-party app (Good). |

Security settings applied via Exchange ActiveSync Polices. |

| iOS Devices | S/MIME.

IRM: Requires third-party app. |

Security settings applied via Exchange ActiveSync Polices. |

| Good for Enterprise

(iOS, Android, Windows Phone) |

Data at rest and in transit is encrypted with strong AES 192-bit encryption.

S/MIME. IRM: Requires third-party app. |

Data containerization via Good Enterprise container.

Security settings applied via Good Mobile Control Policies. |

| Android | S/MIME: Requires third- party app.

IRM: Requires third-party app. |

Security settings applied via Exchange ActiveSync Polices. |

| BlackBerry | Data at rest encrypted with strong AES 256-bit encryption.

Data in transit is encrypted with strong AES 256-bit encryption or Triple Data Encryption Standard (Triple DES). S/MIME. IRM: Requires third-party app. |

Data containerization via BlackBerry Balance technology.

Security settings applied via Exchange ActiveSync Polices. Enterprise Mobility Management provides capability for granular security controls. |

Many organizations are now using Exchange native resiliency to protect against failure. In so doing, they are negating the need to have a point-in-time, offline backup of Exchange data (either on disk or tape). Some organizations, however, will still have a requirement for a point-in-time backup. In the authors' experience, this is usually done to satisfy one of the following criteria:

Should the organization have a requirement to make frequent backups of Exchange data and there is also a strict requirement for data encryption, how the data is secured in long-term storage (on disk or tape) should also be considered. Given the movement of tape media and the likelihood that third parties are involved in that movement to off-site storage, encryption of data stored on disk or tape is imperative. There are two options for encryption of data on tape storage media: software or hardware encryption. Most enterprise-strength tape backup systems, such as IBM's Tivoli Storage Manager with Tivoli Data Protection for databases, use in-built software encryption to satisfy this requirement. Alternatively, there are third-party products that offer software encryption to backups as a bolt-on.

The availability of hardware encryption of tape media depends on the tape device used. In general, hardware encryption offers a lower performance overhead than software-based encryption.

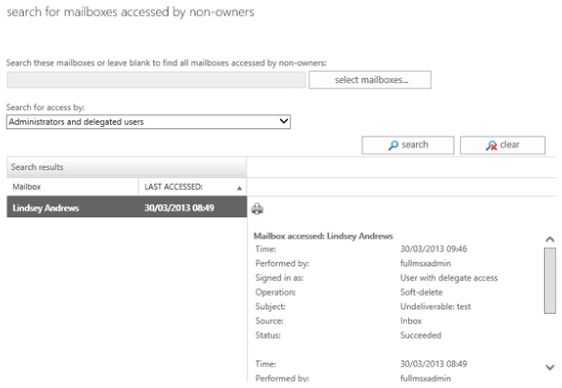

Despite efforts to secure the Exchange environment, should unauthorized access be attempted and be successful, Exchange Server 2013 provides a new auditing interface within the Compliance Management section of the Exchange Administrator Center (EAC) to track access, audit administrator changes, and report on compliance status. The interface is split into two distinct sections, with reporting functionality provided on the left and the functions to export mailbox and administrator audit logs on the right, as shown in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.6 Auditing capabilities within Exchange Server 2013

More information on auditing reports can be found in the following TechNet article:

http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/jj150497(v=exchg.150).aspx

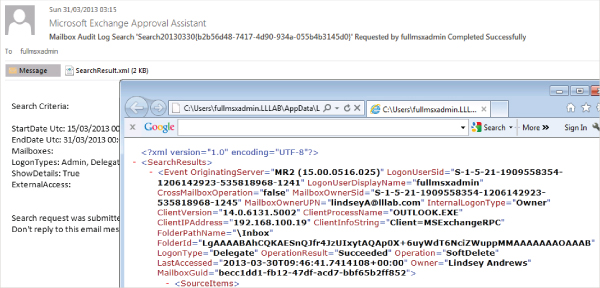

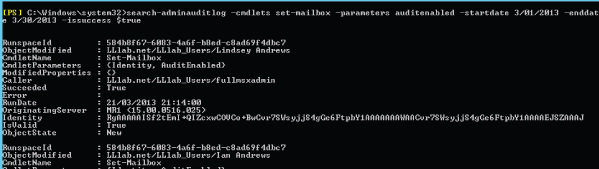

This section is provided as an overview for the reader and to illustrate the types of results gained from searches and the output of the reports.