Chapter 11

Extending Exchange

As a messaging platform, Exchange has grown over the years into a highly competent and cohesive system with a vast range of functionality. Nevertheless, that doesn't preclude Microsoft from extending Exchange's functionality or leveraging it through other systems.

This chapter examines the use of Exchange as a messaging platform to build upon and touches on where it resides within the Microsoft catalog of products. We will begin by investigating the concepts and capabilities Exchange provides to developers for creating custom solutions, and we will then discuss the thought processes behind integrating Exchange with other Microsoft and non-Microsoft systems.

In this chapter, we will examine how you can use the development interfaces provided by Exchange 2013 to meet the business requirements that you may have for your email system that can't be solved with the standard out-of-the box features of the product. First, we will cover the interfaces that are available to create applications, scripts, and add-ins in Exchange 2013, and then we will cover how you can go about writing application code.

This chapter will focus on using Exchange Web Services (EWS), which is now the primary application programming interface (API) for developing code that accesses an Exchange mailbox. We will also look at a few of the new and exciting features in Exchange 2013, such as in-place eDiscovery and mail apps for Outlook, and we will discuss how these new features can be leveraged as solutions in your environment.

As with many other Microsoft products, Exchange 2013 comes with a rich array of development interfaces that allow you to extend and customize the functionality of the product. For IT professionals, it can be confusing trying to decide when you should consider using these development interfaces, and the very mention of writing code can send some scurrying for cover. However, if you really want to add value to your Exchange Server organization, even some simple PowerShell scripts can save you a lot of money on third-party software and give you a rapid return on investment.

A major reason why you may find yourself turning to the development interfaces occurs when you try to fulfill a request for functionality that cannot be provided using the standard features of the product. Also, those who are managing very large Exchange environments can benefit greatly from the ability to write custom reports for otherwise standard requests, such as mailbox usage, message tracking, or the ability to configure certain mailbox features and settings automatically. Automation of these types of tasks can greatly reduce the number of man-hours required to manage a complex environment while simultaneously making your end users more productive. Another instance when you may want to look at the development interfaces occurs when you have a great idea and need to create a new and innovative client application.

Where do you start and what can you do? As soon as you mention development, many IT professionals think of off-the-shelf product applications. While this is one part of the development ecosystem, the Exchange development space also involves other, more home-brew-type projects. Here are some examples:

Many of these tasks can be performed with a minimal amount of code and development skills, so they are not out of reach for most IT professionals willing to stretch themselves a bit. In the end, any code or script you create is just a list of instructions that you're asking the server to perform on your behalf. What takes time is working out the order and logic of those instructions and then reading the results. While this process can be time consuming, the reward of increased agility in problem solving and the rapid return on investment are well worth it.

Exchange 2013 builds on the existing development interfaces introduced in previous versions of Exchange to provide a richer development experience, particularly focused on using standard Internet protocols such as HTTPS. As already mentioned, EWS has been promoted to the primary API for developing applications that run against an Exchange mailbox in Exchange 2013. EWS uses SOAP (XML) to provide the standard message format for the exchange of information between the Exchange Server and your application client.

While the Outlook client still primarily uses MAPI to access the Exchange store (albeit tunneled through RPC over HTTPS), new Exchange 2013 features, such as in-place eDiscovery and mail apps, use EWS as the endpoint for accessing Exchange.

If you have made the decision to write some Exchange code but you're not a developer, just where to begin can be a little confusing. The first question to ask if you want to do something simple is, “Can I write a PowerShell script that uses EWS to accomplish the tasks I want to perform?” PowerShell scripts require a minimum of investment, and they can be written in a text editor like Notepad or a visual IDE, such as the PowerShell IDE or PowerGUI. Such visual scripting IDEs simplify the process of creating scripts, and they also allow the use of code snippets, which can save you a lot of time. Code snippets are partial or fully formed code blocks that you can copy and paste into your own application code or script. These can greatly reduce the amount of time it takes to prototype an application or script. The next step up from writing a simple script is creating a .NET application. For this, you will need Visual Studio. If you are a first-time developer, Microsoft provides a free version of Visual Studio called Visual Studio Express that you can use to build .NET applications.

If you are still not sure about EWS and what you can access using it, there is a great tool produced by Matt Stehle, a Microsoft senior application development manager. The tool is called the EWSEditor, and you can download it at http://ewseditor.codeplex.com/. With this simple GUI application, you can execute most of the EWS operations without needing to write any code, as well as view the syntax used in the requests and responses that may be important if you are building code that uses raw SOAP.

All EWS operations are executed through a Client Access Server (CAS) in your Exchange organization. On each CAS, there is a virtual directory in IIS that points to the underlying EWS files, such as exchange.asmx and service.wsdl, which we will discuss later. To allow any piece of EWS code to post requests to Exchange, you need to specify the URL path to the EWS exchange.asmx file. The URL that you would use within your code to connect to Exchange is usually determined using Autodiscover, which was covered in Chapter 3, “Exchange Architectural Concepts.” The URLs that Autodiscover returns are those that are configured via the Set-WebServicesVirtualDirectory EMS cmdlet. If you need to know the URL to use for EWS and you can't obtain it via Autodiscover, you can find it using the Get-WebServicesVirtualDirectory -Identity EMS cmdlet. For example, review the following code snippet:

Get-WebServicesVirtualDirectory -Identity EWS(Default Web Site)

One of the big advantages of using EWS is that it's designed to be used over HTTPS. Thus, all the code and scripts you write to use it can be run remotely (where port 443 is available). As a general rule, you should avoid running any code directly on your Exchange Servers—there is little advantage to doing this, and errors in your code or scripts may cause your server to become unreliable. Generally, the default EWS throttling setting within Exchange will offer some protection against errant pieces of code causing problems for your Client Access Servers or Mailbox role servers. If you are planning on doing a lot of development work, it is a good idea to build a virtualized development environment in order to avoid testing your beta code and scripts within your production environment.

Exchange organizations can now be configured in a number of different ways that may affect which APIs you can use to access an Exchange mailbox. For example, in any one organization, mailboxes can be located on-premises, in the cloud, or in a mixture of the two. This leads us to consider the following:

If you are embarking on a new development project, or you are evaluating or writing a scope of works for an application that you're going to ask another company to develop, there are many different aspects to consider. Some of the Exchange APIs, such as the Mailbox APIs MAPI and EWS, have overlapping functionality, while some server-management tasks; for example, require the use of the Exchange Management Shell cmdlets, which are the only method you can use to provision mailboxes.

Choosing the correct API to use for development requires that you map out the requirements of the application that you wish to develop first. Then you can match those requirements against the functionality that each API provides. To demonstrate this, let's look at a few real-world scenarios and the development choices available.

Transport agents provide the ability to extend the functionality of the transport pipeline by allowing you to build custom applications that execute at different points in the transport pipeline. The transport pipeline is the processing that happens on a message as part of the message-transfer process. This starts at the beginning of the SMTP conversation at the TCP connection and runs to the delivery of the message to the Exchange store. Note that transport agents can't be extended to the Mailbox store, so they can't be used to access messages in a mailbox or route messages to particular mailbox folders (other than the Junk Email folder). Some uses for transport agents are gateways to external non-SMTP servers, such as fax or SMS gateways, domain catchalls, enhanced mail routing, or antispam handling.

There are three different types of transport agents:

The transport architecture has been changed in Exchange 2013, and this affects the location and placement of transport agents. The Transport service is now split into three different services. Table 11.1 lists the new services that make up the transport architecture and the transport agents supported by each service.

Table 11.1 Exchange 2013 Transport service and transport agent support

| Service | Agents Supported | Server Role |

| Front End Transport service | SMTP receive agents | Client Access Server |

| Transport service | SMTP receive agents, routing agents, and delivery agents | Mailbox Role Server |

| Mailbox Transport service | No third-party agents supported | Mailbox Role Server |

For more information on developing transport agents, you should download and read the Exchange 2013 Transport Agent SDK from MSDN.

For the sake of completeness, you should be aware of one other development interface—the Exchange ActiveSync protocol. The Exchange ActiveSync protocol is designed to allow mobile devices to synchronize email, calendar, contacts, and tasks with Exchange Server. The XML structures used within the Exchange ActiveSync protocol are tokenized, meaning that they are more compact, which reduces the size of the data transferred between the server and the client.

Other features included in Exchange ActiveSync are policy mechanisms used to enforce standard configuration settings on mobile devices. ActiveSync is the best protocol to use when building a mobile device email client because of the policy and tokenization features. Nevertheless, custom mobile applications that need to access just one type of mailbox data may make better use of EWS, which will reduce the overall development effort needed to build and maintain an application.

In this section, we will go into detail about what EWS is and how you can use it. While this may have a slight developer slant to it, the information covered is important to understand when using EWS.

EWS is now the preferred API to use when building applications in Exchange 2013. It was introduced in Exchange 2007, and it allows access to Exchange mailbox data and allows you to perform mailbox client functionality such as Out of Office (OOF), free/busy lookups, and so on. EWS uses SOAP (XML) to provide the standard message format for the exchange of information between the Exchange Server and the client. There is nothing you need to do to enable EWS in your Exchange environment, because it's enabled by default and used in many of the core areas in Exchange. For example, since Outlook 2007 and Exchange 2007, EWS has been used to provide access to OOF and free/busy information. In Exchange 2013, the new eDiscovery functionality is built on top of EWS. EWS is backward compatible with Exchange Server dating back to version 2007. However, newer features and operations are only available in certain versions of Exchange, so it is important that you take this into consideration if you are supporting multiple version of Exchange.

A major advantage of EWS compared to other mailbox access APIs is that all communication between the client and server is performed over HTTPS. This allows you to take full advantage of the flexibility and functionality of web services technology in your client applications. It also means that any client that supports these standard Internet protocols, regardless of operating system, can run applications that can interact with an Exchange mailbox via EWS. This allows you to support both Windows and non-Windows platforms, such as Linux, Apple's iOS, and Android.

In Exchange 2013, EWS has been enhanced to provide support for new server functionality as well as improved accessibility to existing mailbox data. New features in EWS in Exchange 2013 include the following:

When you're thinking about writing code for EWS, there are three methods that can be used: the EWS Managed API, Web Services Description Language proxy objects, and raw SOAP. The actual method you use will depend on the platform in use and the language in which you wish to write the code. For most development scenarios involving .NET applications, the EWS Managed API is the best method of the three because it greatly reduces the amount and complexity of the code you need to write.

Following is a description of the three different available methods.

If you're developing applications that will run on a Windows platform in .NET, the ESW Managed API offers the best and easiest method for building Exchange applications. The EWS Managed API is a Microsoft-developed and supported client-side library that offers an intuitive object model, which reduces the complexity of the code you need to write. This both reduces the time it takes to develop an application and makes for less-error-prone code. Another advantage of the EWS Managed API is the detailed documentation and number of examples available from Microsoft and third-party websites. All of the samples shown in this chapter make use of the EWS Managed API.

Most development applications, such as Visual Studio, support the ability to scan for the operations provided by a particular web service. To do this, they use the Web Services Description Language (WSDL) file for the web service and generate strongly typed objects based on this definition. These objects allow you to write code more easily using a standardized object model, without needing to worry about the serialization and deserialization of the web service's SOAP requests and responses. The difference between this and the EWS Managed API is that the latter's objects are designed to be more developer friendly and intuitive, which reduces the amount of code you need to write, thus decreasing complexity and debugging time. Nonetheless, proxy code is still useful in that some EWS operations aren't included in the EWS Managed API.

For some applications where you can't use the EWS Managed API or proxy code, using raw SOAP is the only option. An application that uses raw SOAP requests must build the XML EWS SOAP request manually and parse the XML SOAP responses that are returned from the server. An example of an application that makes use of raw SOAP requests and responses is the makeEWSRequestAsync method of the Office JavaScript API that is utilized in the mail app for Outlook, a new feature in Office 2013 and Exchange 2013.

The first thing that any EWS application requires is that you discover and authenticate to the CAS through which the EWS requests will be communicated. Autodiscover is the best method for discovering the EWS URL for a Client Access Server in most organizations. With the EWS Managed API, SOAP-based Autodiscover is used, which is the most efficient method. However, if you aren't using the EWS Managed API, you may want to look at using POX-based Autodiscover.

Plain Old XML (POX) Autodiscover allows you to send a plain XML Autodiscover request and retrieve the configuration information from a mailbox that will include the EWS URL of the CAS to which to send EWS requests. The POX request/response is what you see when you perform an Outlook test autoconfiguration. Listing 11.1 shows POX-based Autodiscover in action.

Listing 11.1: How to perform a POX-based Autodiscover against Exchange Online using C#

//SMTP Address of Mailbox

String MbMailbox = "user@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

//UserName and Password of account to use for authentication

String UserName = "upn@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

String Password = "password123";

//Autodiscover End Point for Office365

String AutoDiscoURL = "https://autodiscover-s.outlook.com/autodiscover/autodiscover.xml";

NetworkCredential ncCred = new NetworkCredential(UserName,Password);

String EWSURL = null;

String auDisXML = "<Autodiscover xmlns=\"http://schemas.microsoft.com/exchange/autodiscover/outlook/requestschema/2006\"><Request>" +

"<EMailAddress>" + MbMailbox + "</EMailAddress>" +

"<AcceptableResponseSchema>http://schemas.microsoft.com/exchange/autodiscover/outlook/responseschema/2006a</AcceptableResponseSchema>" +

"</Request>" +

"</Autodiscover>";

System.Net.HttpWebRequest adAutoDiscoRequest = (System.Net.HttpWebRequest)System.Net.HttpWebRequest.Create(AutoDiscoURL);

byte[] bytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(auDisXML);

adAutoDiscoRequest.ContentLength = bytes.Length;

adAutoDiscoRequest.ContentType = "text/xml";

adAutoDiscoRequest.Headers.Add("Translate", "F");

adAutoDiscoRequest.Method = "POST";

adAutoDiscoRequest.Credentials = ncCred;

Stream rsRequestStream = adAutoDiscoRequest.GetRequestStream();

rsRequestStream.Write(bytes, 0, bytes.Length);

rsRequestStream.Close();

adAutoDiscoRequest.AllowAutoRedirect = false;

WebResponse adResponse = adAutoDiscoRequest.GetResponse();

String Redirect = adResponse.Headers.Get("Location");

if (Redirect != null)

{

adAutoDiscoRequest = (System.Net.HttpWebRequest)System.Net.HttpWebRequest.

Create(Redirect);

adAutoDiscoRequest.ContentLength = bytes.Length;

adAutoDiscoRequest.ContentType = "text/xml";

adAutoDiscoRequest.Headers.Add("Translate", "F");

adAutoDiscoRequest.Method = "POST";

adAutoDiscoRequest.Credentials = ncCred;

rsRequestStream = adAutoDiscoRequest.GetRequestStream();

}

rsRequestStream.Write(bytes, 0, bytes.Length);

rsRequestStream.Close();

adResponse = adAutoDiscoRequest.GetResponse();

Stream rsResponseStream = adResponse.GetResponseStream();

XmlDocument reResponseDoc = new XmlDocument();

reResponseDoc.Load(rsResponseStream);

XmlNodeList pfProtocolNodes = reResponseDoc.GetElementsByTagName("Protocol");

foreach (XmlNode xnNode in pfProtocolNodes)

{

XmlNodeList adChildNodes = xnNode.ChildNodes;

foreach (XmlNode xnSubChild in adChildNodes)

{

switch (xnSubChild.Name)

{

case "EwsUrl": EWSURL = xnSubChild.InnerText;

break;

}

}

}

POX-based Autodiscover was deemphasized in Exchange 2010 in favor of SOAP-based Autodiscover. The latter has the advantage of supporting batch requests when you need to perform discovery for multiple users in one operation. SOAP-based Autodiscover also provides the ability to request only those settings that you need, and this reduces the size of the Autodiscover response.

Listing 11.2 shows how to perform a SOAP-based Autodiscover. The process is as follows: When using the EWS Managed API to perform an Autodiscover, the client-side library will first try to discover the EWS endpoint using the Active Directory SCP records. If this lookup fails, DNS Autodiscover is then tried. In some Exchange organizations, disabling the first SCP check would provide a more optimized discovery. To do this, the EnableScpLookup property can be used.

Listing 11.2: How to perform a SOAP-based Autodiscover using the EWS Managed API to get the EWS URL and version of Exchange

String MbMailbox = "user@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

String UserName = "upn@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

String Password = "password123";

NetworkCredential ncCred = new NetworkCredential(UserName, Password);

String EWSURL = null;

String EWSVersion = null;

//Create Autodiscover Object

AutodiscoverService asAutodiscoverService = new AutodiscoverService();

//Set Credentials

asAutodiscoverService.Credentials = ncCred;

asAutodiscoverService.EnableScpLookup = false;

asAutodiscoverService.RedirectionUrlValidationCallback = RedirectionUrlValidationCallback;

//Define array for setting to retreive

UserSettingName[] unUserSettings = new UserSettingName[2] { UserSettingName.ExternalEwsUrl,UserSettingName.ExternalEwsVersion };

GetUserSettingsResponse adResponse = asAutodiscoverService.GetUserSettings(MbMailbox, unUserSettings);

//Retrieve the Results from the Autodiscover response

EWSURL = (String)adResponse.Settings[UserSettingName.ExternalEwsUrl];

EWSVersion = (String)adResponse.Settings[UserSettingName.ExternalEwsVersion];

Authentication is an important consideration when creating an application or script that uses EWS. By default, users in Exchange can access only their own mailbox and nothing beyond basic free/busy information for other users. This means that if your application is going to access mailboxes other than that belonging to the current user (the user running the application), you will need to configure permissions on the mailboxes you wish to access.

EWS supports several authentication methods. As you would expect, NTLM and Basic authentication are available, plus Exchange 2013 adds the new token authentication using server-to-server authentication (OAuth). This allows you set up partner applications whereby you can authenticate and create a token in one application and then use that token to authenticate to Exchange or another third-party web service without specifying the credentials for that user. The two partner applications that Exchange 2013 supports at release to manufacturing (RTM) are Lync 2013 and SharePoint 2013, both of which support OAuth and server-to-server (STS) authentication. Once EWS is configured, you can generate a token on SharePoint 2013 or Lync 2013 and then use this token to authenticate with Exchange.

Another use of token authentication is to help support single sign-on in mail apps for Office. The EWS Managed API now includes a partner DLL library named Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Auth.dll, which is used to validate user-identity tokens sent from an Exchange Server so that your third-party web service can implement authentication for these claims.

Token authentication facilities in Exchange 2013 provide the power to build applications that support single sign-on (SSO) authentication. Exchange 2013 uses the JSON web token (JWT) format for identity tokens. The token is signed but not encrypted, using a public key that is held and replicated to all Exchange Servers in your Exchange organization.

An example where token authentication can be used is in mail apps for Office. Within the mail app, you can generate a token that can then be used to make a request to another web service within your organization that requires user authentication. The other (non-Exchange) server that you want to authenticate against must have the ability to validate the token and then associate the unique identifier from the token with a set of credentials for which you're requesting access. To validate a token, a server application can use the validation library from the Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Auth.dll partner library included with the EWS Managed API.

The other way of using token authentication is by setting up a partner application in Exchange 2013. This is done using the Configure-EnterpriseApplication.ps1 script that is included with Exchange. For example, with this script you can set up Lync 2013 or SharePoint 2013 to be a supported partner application. This means that you can generate tokens within your SharePoint or Lync applications and then use these tokens to authenticate against a user's mailbox to retrieve mailbox data. This can allow you to extend your SharePoint and Lync applications into the Exchange data store without the need to prompt the user for credentials.

More information and guidelines for using token authentication are found in the Exchange SDK http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/exchange/.

EWS has two authentication access modes that can be used when accessing a mailbox other than the primary mailbox or the archive associated with the account being used to authenticate to Exchange. EWS impersonation can be used when you have an application or service account that needs to access many accounts. When impersonation is used, the application or service user account that has been granted impersonation rights will have the same rights as the user whom they are impersonating. This allows you to have an application act on a mailbox's data as the owner and provides the security implications that go along with this. There is no way to constrain impersonation in Exchange, that is, to constrain it to just the Calendar folder. Thus, once access is granted, the impersonator will always have full rights or owner access to a mailbox. Another constraint of impersonation is that you can't impersonate a disabled account. For example, when the Meeting Room and Resource mailboxes are disabled by default, these accounts cannot be impersonated by default. Listing 11.3 demonstrates how to use impersonation in the EWS Managed API to impersonate another user and access that user's inbox.

Listing 11.3: How to use impersonation in the EWS Managed API to impersonate another user and access that user's inbox

String UserName = "ApplicationUserName"; String Password = "ApplicationPassword"; String Domain = "exchange-d3"; String EmailAddress = "user@exchange-d3.com"; var Version = ExchangeVersion.Exchange2013; ExchangeService service = new ExchangeService(Version); service.Credentials = new NetworkCredential(UserName, Password, Domain); service.AutodiscoverUrl(EmailAddress); //Set Impersonation to the Target Mailbox you want to impersonate service.ImpersonatedUserId = new ImpersonatedUserId(ConnectingIdType.SmtpAddress, UserPrimarySMTPAddress); //Bind to the Inbox folder of the Impersonated Mailbox Folder InboxFolder = Folder.Bind(service, WellKnownFolderName.Inbox);

The other access mode available is EWS delegation. This is the conventional method to use when a user account needs to access a mailbox other than its own. Delegation means that discretionary access control lists (DACLs) on the mailbox and mailbox folders are used to determine whether the requesting user can access a mailbox or particular mailbox folder. The advantage delegation may have over impersonation is the ability to constrain the access to resources. For example, if the application you are creating needs to access only the Contacts folder of the other user's mailbox, then rights need to be granted only to this particular folder. Full rights can also be granted explicitly to the mailbox via the Add-MailboxPermissions cmdlet. Listing 11.4 demonstrates how to use delegation in the EWS Managed API to access another user's inbox.

Listing 11.4: How to use delegation in the EWS Managed API to access another user's inbox

ExchangeService service = new ExchangeService(ExchangeVersion.Exchange2013); service.Credentials = new NetworkCredential(ApplicationUserName, ApplicationPassword, Domain); service.AutodiscoverUrl(ApplicationEmailAddress); //Specifiy the SMTP Address of the destination Mailbox in the FolderId FolderId InboxFolderId = new FolderId(WellKnownFolderName.Inbox, "User@exchange-d3.com"); //Bind the delegate's Inbox Folder InboxFolder = Folder.Bind(service, InboxFolderId);

In terms of data, when you break down what constitutes a mailbox, it's pretty simple: A mailbox is a container that holds folders, each containing items and other folders. A folder itself has three collections: one for normal items, one for folder associated items (FAI), and a third for soft deleted items, which was used in previous versions of Exchange and more commonly known as the dumpster of a folder.

The dumpster's operation changed in Exchange 2010 with the introduction of single item recovery (SIR), so you no longer need to be concerned with it. With SIR enabled, when you Shift-Delete an item from a folder or when it is purged from deleted items, it is copied into the Recoverable Items folder under the NON_IPM_Subtree of a mailbox (for the duration of the retention period).

To access a folder or item using EWS, you must know the EWS identifier associated with that item or folder. This EWSID is a Base64 encoded identifier that Exchange will use to determine what object you want to access. These IDs change on items and folders. For example, if an item is moved between folders, deleted, or copied, a new ItemID is created for the copied item. The fact that these ItemIDs can change means that you should be careful when using them as permanent, non-changing identifiers that you can reference in your application. While the ID won't change if the item doesn't change location in the mailbox, once an ItemID has changed, there is no way to search for the item based on the old identifier. This means your application likely won't function. This is where storing other identifiers, such as pidtagSearchKey, can be useful. This ID doesn't change, and it can be used to search for an item that has been deleted, for instance, and may now be in the Recoverable Items folder mentioned earlier.

To determine what the EWSID is for a particular item or folder, Exchange provides two search operations. The first is called FindFolders, and it allows you to search for folders in a mailbox. The second is called FindItems, and, as the name suggests, it allows you to search for items within a particular folder. These search operations can be used with search constraints, called restrictions in EWS, or SearchFilters in the EWS Managed API.

The heart of the Exchange Server product is the Information Store service, which acts as a special type of database and property store. In Exchange, instead of a single email being stored as one object or a large binary blob, it is stored as a collection of properties in the Exchange store. The manner in which these properties are stored in the Exchange database has changed and evolved as the information store developed. IT professionals who are familiar with information store development over the years are aware of the storage enhancements that have continued into Exchange 2013. However, the way in which these properties are enumerated, primarily via MAPI since the early versions of Exchange, has remained unchanged. The one thing to keep in mind that can impact the performance of any programmatic operation you do is that some properties are real, while others are calculated; some may also be indexed, while others are not.

A basic example of a property of an object is the subject of a message. In EWS, there are strongly typed objects for the common object types you use in Exchange, such as email messages, contacts, and appointments. These strongly typed objects provide access to the first-class object properties like the subject, body, sender, recipients, and so forth. These strongly typed objects and properties, however, don't cover all of the properties of a message. Exchange also allows for the provision of custom properties by users and application developers to support the needs of custom workflows and applications.

Any property in EWS can be accessed and set via the extended property definition, which contains information about the data type of the property and a property identifier that uniquely identifies the property. In reality, however, you only need to use extended properties when no strongly typed property definition exists. To demonstrate this concept, following is an example of setting the subject on an email message using the Managed API via the strongly typed email message object's subject property:

EmailMessage message = new EmailMessage(service); message.Subject = "Email Subject";

This is an example of setting the subject using its extended property definition:

// Example of setting the Extended property for the subject on a message EmailMessage message = new EmailMessage(service); ExtendedPropertyDefinition pidTagSubject = new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(0x0037, MapiPropertyType.String); message.SetExtendedProperty(pidTagSubject, "Email Subject");

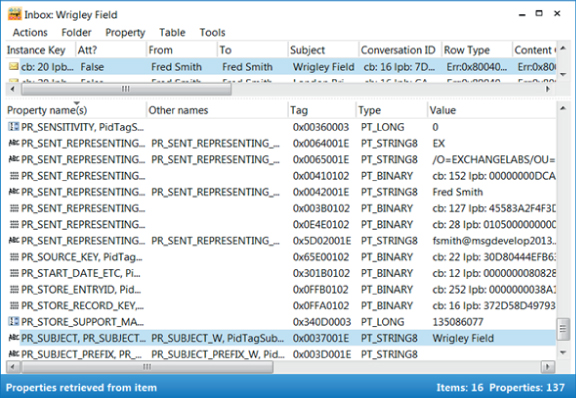

The idea of these examples is that when you're writing a program or script, you may see a property in Outlook that you can't find as a property in the Managed API or WSDL object classes. In such cases, you will need to use the extended property definition to set, change, or remove these properties. To help you determine what the property tags and property data types should be for an extended property definition, you should use a MAPI editor like OutlookSpy or MFCMapi. These MAPI editors allow you to view all of the extended properties of a particular Exchange object, which is an invaluable tool when doing any Exchange development. Figure 11.1 shows the Subject property highlighted in MFCMapi. Under the Tag column, you will see 0x0037001E listed. In this example, the 0x0037 is the property tag and 001E is the data type.

Figure 11.1 MFCMapi to show the extended property ID of the Subject field of a message

If you are writing an application that requires access to one of the well-known folders in a mailbox, such as the Inbox, Contacts, Calendar, Journal, or Sent Items, EWS provides a direct method for accessing these folders through the distinguished folderIdTypes. This allows you to refer to a folder using a more user-friendly name and have Exchange still understand what you mean. It also allows you to deal with issues surrounding localization, when you have mailboxes that use different languages. In the case where your mailbox has a localized Inbox, Calendar, or Contacts folder display name, the same distinguished name is still used. With the EWS Managed API, this is provided via the WellKnownFolderName enumeration. The WellKnownFolderName enumeration maps to the distinguished folderIdType, and it is the easiest way of obtaining access to many important folders within a mailbox. For example, to access a user's Calendar folder, you can use the following code:

CalendarFolder CalFld = Folder.Bind(service,WellKnownFolderName.Calendar);

If you wanted to access a user's Recoverable Items folder (the Dumpster, v2) instead, you could use the following code:

Folder RecoverableItemsDeletions = Folder.Bind(service,WellKnownFolderName.RecoverableItemsDeletions)

Once more, if you want to access the user's Archive mailbox, you can use the following code:

Folder AFld =Folder.Bind(service,WellKnownFolderName.ArchiveMsgFolderRoot);

As you can see, these are all relatively straightforward. If instead of accessing one of the well-known folder types you need to access a user-created folder, such as one that is a subfolder of the Inbox, then you need to use the FindFolders operation to search for a folder based on a search parameter. For example, Listing 11.5 illustrates how to address a subfolder of the Inbox by searching for it based on the folder's display name.

Listing 11.5: How to address a subfolder of the Inbox by searching for it based on the folder's display name

Folder InboxFolder = Folder.Bind(service, WellKnownFolderName.Inbox);

SearchFilter FolderSearchFilter = new SearchFilter.IsEqualTo(FolderSchema.DisplayName, FolderName);

FolderView FolderView = new FolderView(1);

FindFoldersResults ffResults = InboxFolder.FindFolders(FolderSearchFilter, FolderView);

if (ffResults.TotalCount == 1)

{

Folder SubFolder = ffResults.Folders[0];

}

Just like accessing folders, to access an item using EWS, you need to know its EWSID. Unlike folders, however, there are no WellKnownItemIDs, so unless you have stored the EWSID externally, perhaps in a SQL database, to access any mailbox item you will first be required to use the FindItems operation. The FindItems operation in EWS allows you to enumerate the items within a mailbox folder, with or without a search clause. For example, Listing 11.6 demonstrates how you can enumerate all of the items within a particular mailbox's Inbox folder and output the subject. This example shows you how to use paging, which means telling the server in the request to return large result sets in smaller increments. This is an important method to use when working with Exchange 2010 and above because of the implementation of throttling. In order not to overload the server and run afoul of throttling, we have asked the server to return only 1,000 items at a time per request. Refer to the following site for more information about throttling:

http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dd297964%28v=exchg.141%29.aspx

Listing 11.6: How you can enumerate all of the items within a particular mailbox's Inbox folder and output the subject

Folder InboxFolder = Folder.Bind(service, WellKnownFolderName.Inbox);

ItemView itItemView = new ItemView(1000);

FindItemsResults<Item> fiResults = null;

do

{

fiResults = InboxFolder.FindItems(itItemView);

foreach (Item itItem in fiResults.Items) {

Console.WriteLine(itItem.Subject);

}

itItemView.Offset += fiResults.Items.Count;

} while (fiResults.MoreAvailable == true);

While enumerating items may be okay for some scenarios, in most instances where you need to access items, you will need to use a search restriction. A search restriction is analogous to a where clause in a SQL query, and it limits the items that a FindItems operation will return. In Exchange 2013, as well as the Exchange store search and the Exchange Search service (content indexing), EWS supports searching all folders within a mailbox in a single operation using the new eDiscovery operations.

The Exchange Search service allows you to query Exchange's content indexes. This gives you the ability to query text within messages and indexed properties more easily, without the need for an expensive item-filter operation. In this context, we consider expensive to mean something that has a significant impact on the performance of a server and/or the amount of time it takes to return the results to the requesting user. The Exchange Search service runs on the Mailbox server, and it is responsible for building and maintaining the content indexes. New messages are indexed as soon as they arrive in a mailbox folder, which ensures these indexes are always up to date. Exchange Search also allows you to search for content inside attachments (that is, for attachment types for which an IFilter is available on the server). The attachment content search feature is an exclusive one that is not available by means of an Exchange store search. (See the “Exchange Store Search” section that follows.)

Exchange Search uses search-optimized indexes to provide a reliable and consistent method for querying mailbox items. However, because the number of properties that are included in these indexes is limited, it is not always possible to make use of a content index search, depending on the particular properties that you might need to query. Listing 11.7 shows how you can use an Advanced Query Syntax (AQS) filter to search for a message.

Listing 11.7: Using an AQS string to search for messages

String AQSString = "Subject:\"Good Coffee\""; ItemView itemview = new ItemView(1000); FindItemsResults<Item> fiitems = FindItems(WellKnownFolderName.Inbox, AQSString, itemview);

Exchange store search is the conventional search method that has been used since Exchange 2007. It represents an evolution of previous search services used by the Exchange Mailbox store. If you used filtering in CDO 1.1 or exMAPI, then you have used the Exchange store search. Exchange store search creates a dynamic restriction on the folder you are querying that is similar to how a Search folder works. Exchange store search performs a sequential scan of all messages in the target search scope on the Exchange Server. Because no indexes are used, there are no restrictions on the properties that can be queried. Nevertheless, on folders with a large number of items, these types of queries may not perform optimally and may also impact overall server performance. Sample code needed to perform an Exchange store search is shown in Listing 11.8.

Listing 11.8: Using a search filter to perform an Exchange store search

[Updated GS] String SrchValue = "Good Coffee"; var SrchProp = EmailMessageSchema.Subject; ItemView iv = new ItemView(1000); SearchFilter sf = new SearchFilter.ContainsSubstring(SrchProp, SrchValue); FindItemsResults<Item> fiResults = null; fiResults = service.FindItems(WellKnownFolderName.Inbox, sf, iv);

In-place eDiscovery is a new feature introduced in Exchange 2013 that allows you to use EWS to search all folders in a mailbox with a single operation. It also contains a variety of new features and actions that can be used either via the eDiscovery console, which is available to IT professionals and administrators, or programmatically within an application or script. Table 11.2 lists the new operations that have been added to EWS to support eDiscovery.

Table 11.2 New operations added to EWS to support eDiscovery

| Operation Name | Description |

| GetHoldOnMailboxes | Gets the status of a query-based hold, which is set using the SetHoldOnMailboxes operation |

| GetSearchableMailboxes | Gets a list of mailboxes on which the client has permission to search or perform eDiscovery |

| SearchMailboxes | Searches for items in specific mailboxes that match query keywords |

| SetHoldOnMailboxes | Sets a query-based hold on items |

In-place eDiscovery is really more than a series of new search operations—it's the new strategy for dealing with “big data” stored within mailboxes and archives. With mailbox capacities expected to average 100 GB in the near future, this feature will become increasingly important in enabling you to handle the data stored in these large mailboxes in the future. The eDiscovery operations that are now part of EWS allow you more easily to query data, place a hold on items to prevent their removal, and de-duplicate the items found to help with the processing of the discovered data. De-duplication means that if an individual item is the same as other search results, it will be shown only once in the results. The log will show all of the locations of that file. While many of these features are designed to be used in a legal context, they are extensible for use in many other application scenarios.

Keyword Query Language (KQL) has been introduced in Exchange Server 2013 for use in building search criteria for any eDiscovery operations you wish to perform. A KQL query consists of one or more free-text keywords or phrases and/or property restrictions. In addition, you can combine KQL query elements with one or more of the available operators to build more complex queries. In this context, operators are things like the Boolean AND and NOT or equate operations like = or <, >. KQL queries are case-insensitive and limited to 2,048 characters. An example of making a free-text KQL query for the phrase “Microsoft Exchange 2013” would be as follows:

MailboxQuery mbq = new MailboxQuery("\"Microsoft Exchange 2013\"", msbScope);

An example of using a property restriction where you wanted to search for messages where the subject was “Microsoft Exchange 2013” would be as follows:

MailboxQuery mbq = new MailboxQuery("Subject:\"Microsoft Exchange \"", msbScope);

Wildcards are also supported in KQL queries. For example, you might want to write a query like the one in Listing 11.9 to find the number of hits obtained for a query for Exchange 20x compared to one for Exchange 2003.

Listing 11.9: Using wildcards with the MailboxQuery class

MailboxQuery mbq = new MailboxQuery("Exchange NEAR(1) 20*", msbScope);

MailboxQuery mbq2 = new MailboxQuery("Exchange NEAR(1) 2003", msbScope);

MailboxQuery[] mbqa = new MailboxQuery[2] { mbq,mbq2 };

When you perform an eDiscovery operation, you have the option of either getting only statistics or retrieving results in preview items format. Getting the statistics means that you will get an estimate of the number of messages the search will return for each of the keywords or search predicates you use. This can be useful if you're looking to find the most efficient query to make or the correct operator to use. For example, if you have a folder used to store a mailing list where people talked about problems with their Exchange Server, then you could use the sample code in Listing 11.10 to determine the number of items where the different versions of Exchange were discussed.

Listing 11.10: Using the NEAR operator with the MailboxQuery class

MailboxQuery mbq2 = new MailboxQuery("Exchange NEAR(1) 2003", msbScope);

MailboxQuery mbq3 = new MailboxQuery("Exchange NEAR(1) 2007", msbScope);

MailboxQuery mbq4 = new MailboxQuery("Exchange NEAR(1) 2010", msbScope);

MailboxQuery[] mbqa = new MailboxQuery[4] { mbq1,mbq2,mbq3,mbq4 };

The results you would receive for a statistics-only query would look like those shown in Listing 11.11.

Listing 11.11: eDiscovery search results in statistics format

<t:KeywordStats>

<t:KeywordStat>

<t:Keyword>Exchange NEAR(1) 20*</t:Keyword>

<t:ItemHits>2506</t:ItemHits>

<t:Size>477698732</t:Size>

</t:KeywordStat>

<t:KeywordStat>

<t:Keyword>Exchange NEAR(1) 2003</t:Keyword>

<t:ItemHits>1248</t:ItemHits>

<t:Size>375585600</t:Size>

</t:KeywordStat>

<t:KeywordStat>

<t:Keyword>Exchange NEAR(1) 2007</t:Keyword>

<t:ItemHits>1197</t:ItemHits>

<t:Size>129445974</t:Size>

</t:KeywordStat>

<t:KeywordStat>

<t:Keyword>Exchange NEAR(1) 2010</t:Keyword>

<t:ItemHits>91</t:ItemHits>

<t:Size>4536168</t:Size>

</t:KeywordStat>

</t:KeywordStats>

When you use the preview-only SearchResultType, instead of getting the keyword statistics, you will receive a preview item for each of the keyword item hits. These preview items can be de-duplicated to ensure that the same item isn't shown multiple times. For preview items that are returned, a subset of the most common properties on the items is shown so that you can perform more client-side filtering if required. The preview items can then also be processed separately, and actions like Copy, Move, Delete, or Hold can be performed on each of the search hits.

There are many potential uses for eDiscovery, but it will be used primarily for legal discoveries. These legal discoveries will allow your legal team to search across a selection, or even across all mailboxes, to locate specific data that is perhaps relevant to litigation.

There are several things you need to determine when you want to perform a discovery:

In the next example, Listing 11.12, we are going to do a free-text keyword query using the search term “share trade.” We are going to use the ONEAR operator, which allows us to search for two different keywords that have a variable proximity. In this example, it will search for the word “share” that has the word “trade” within a two-word proximity. This is just one example of the more complex searches that can be performed using KQL and eDiscovery compared to the AQS searches that we had in Exchange 2010.

Listing 11.12: Using eDiscovery to do a proximity search

//Get the Mailboxes to Search using the GetSearchableMailboxes Operation

GetSearchableMailboxesResponse gsMBResponse = service.GetSearchableMailboxes("user@exchange-d3.com", false); MailboxSearchScope[] msbScope = new MailboxSearchScope[gsMBResponse.SearchableMailboxes.Length];

Int32 mbCount = 0;

foreach (SearchableMailbox sbMailbox in gsMBResponse.SearchableMailboxes)

{

//Get the referenceId for the use in the eDiscovery operation

msbScope[mbCount] = new MailboxSearchScope(sbMailbox.ReferenceId, MailboxSearchLocation.All);

mbCount++;

}

SearchMailboxesParameters smSearchMailbox = new SearchMailboxesParameters();

MailboxQuery mbq = new MailboxQuery("\"share\" ONEAR(n=2) \"trade\"", msbScope);

MailboxQuery[] mbqa = new MailboxQuery[1] { mbq };

smSearchMailbox.SearchQueries = mbqa;

smSearchMailbox.PageSize = 1000;

smSearchMailbox.PageDirection = SearchPageDirection.Next;

//Tell Exchange to return Preview Items

smSearchMailbox.ResultType = Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.SearchResultType.PreviewOnly;

ServiceResponseCollection<SearchMailboxesResponse> srCol = service.SearchMailboxes(smSearchMailbox);

foreach (SearchMailboxesResponse srResponse in srCol)

{

foreach (SearchPreviewItem srPvrItem in srResponse.SearchResult.PreviewItems)

{

//Process Item

}

}

The other major function in an application for which you will use EWS is when creating new content within the Exchange store. The EWS Managed API's object model allows for the easy creation of new objects, as shown in Listing 11.13, Listing 11.14, and Listing 11.15. In Listing 11.13, we will look at how you can send email using EWS. When you send an email via EWS, it's like sending email from within a mail client. You can resolve addresses in the global address list using partial matches, choose to blind copy recipients, attach a file, and also save the message in the Sent Items folder if desired. In Listing 11.14, we look at requesting a read receipt on the message that was sent. Finally, in Listing 11.15, we look at how to create a new mailbox contact. The code used to create contacts is more complex because contacts have a larger number of properties.

Listing 11.13: Sending a new email with an attachment using the EWS Managed API

EmailMessage EmailMessage = new EmailMessage(service);

EmailMessage.Subject = "Mondays Sales Reports";

EmailMessage.ToRecipients.Add("recipient@exchange-d3.com");

EmailMessage.Body = "Please see the following attached reports";

EmailMessage.Attachments.AddFileAttachment(@"c:\report\MondayReport.csv");

EmailMessage.SendAndSaveCopy();

Listing 11.14: Additional code to ask for a read receipt on the email in Listing 11.13

EmailMessage.IsReadReceiptRequested = true; EmailMessage.IsDeliveryReceiptRequested = true;

Listing 11.15: Creating a new contact using the EWS Managed API

Contact contact = new Contact(service);

contact.GivenName = "Bob";

contact.Surname = "Smith";

contact.FileAsMapping = FileAsMapping.SurnameCommaGivenName;

contact.DisplayName = "Bob Smith";

contact.CompanyName = "exchange-d3";

contact.PhoneNumbers[PhoneNumberKey.BusinessPhone] = "612-555-0110";

EmailAddress CntEmailAddress = new EmailAddress("BSmith@exchange-d3.com");

contact.EmailAddresses[EmailAddressKey.EmailAddress1] = CntEmailAddress;

// Specify the Business Address.

PhysicalAddressEntry paEntry1 = new PhysicalAddressEntry();

paEntry1.Street = "123 Main Street";

paEntry1.City = "London";

paEntry1.State = "ZZ";

paEntry1.PostalCode = "02002";

paEntry1.CountryOrRegion = "United Kingdom";

contact.PhysicalAddresses[PhysicalAddressKey.Business] = paEntry1;

contact.Save(WellKnownFolderName.Contacts);

Some contact properties aren't definable using the standard EWS strongly typed objects. Thus, if you wish to set these properties, you must use the extended property for each particular property. An example of this is shown in Listing 11.16.

Listing 11.16: Setting the Gender property on a contact

var propType = MapiPropertyType.Short; var propTag = 0x3A4D; var pidTagGender = new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(propTag, propType); contact.SetExtendedProperty(pidTagGender, 2);

Other common objects that you may want to create programmatically are appointments and meeting requests. For instance, you want to add a specific company event or holiday to all of your users' calendars. Meetings and appointments are created the same way in EWS with the exception that meeting requests include attendees. Also, when you call the Appointment class's Save method, you specify in the method's overload those attendees to whom you want the Meeting Request objects sent. Listing 11.17 details how to create meeting requests, and Listing 11.18 shows you how to set a recurring meeting. Finally, Listing 11.19 shows how to create a Task object.

Listing 11.17: Creating a meeting request or appointment

Appointment apt = new Appointment(service);

apt.Subject = "Coffee";

apt.StartTimeZone = TimeZoneInfo.Local;

apt.Start = new DateTime(2012, 12, 24, 11, 0, 0);

apt.End = apt.Start.AddHours(1);

apt.EndTimeZone = apt.StartTimeZone;

apt.RequiredAttendees.Add("user@exchange-d3.com");

apt.Save(SendInvitationsMode.SendToAllAndSaveCopy);

Listing 11.18: Setting a recurring meeting

DayOfTheWeek[] days = new DayOfTheWeek[] { DayOfTheWeek.Monday };

apt.Recurrence = new Recurrence.WeeklyPattern(appoint.Start.Date, 1, days);

apt.Recurrence.StartDate = appoint.Start.Date;

Listing 11.19: Creating a task request

Task task = new Task(service); task.Subject = "World peace"; task.DueDate = new DateTime(2013,1,1,12,0,0); task.Body = "Archive world peace"; task.Save(WellKnownFolderName.Tasks);

The EWS Managed API has object classes to cater to the most commonly-used Exchange item types such as email, calendar, contacts, and appointments. However, for other item types such as notes and journal entries, no strongly typed object is available in EWS. To create one of these item types when there is no corresponding strongly typed object in EWS, use the EmailMessage class (MessageType in WSDL proxy code) and then modify the ItemClass property. For all of the other properties of that particular object, you need to use the corresponding extended property. Listing 11.20 shows you how to create Exchange rich item types like sticky notes.

Listing 11.20: Creating other Exchange rich item types like sticky notes

EmailMessage sn = new EmailMessage(service);

sn.ItemClass = "IPM.StickyNote";

Guid guid = new Guid("0006200E-0000-0000-C000-000000000046");

var Ptype = MapiPropertyType.Integer;

var clr = 0x8B00; //Colour Prop Tag

var wdt = 0x8B02; //Width Prop Tag

var hgt = 0x8B03; //Height Prop Tag

var lft = 0x8B04; //Left Prop Tag

var Top = 0x8B05; //Top Prop Tag

String BodyText = "Test Body of to Note";

var BodyType = Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.BodyType.Text;

sn.SetExtendedProperty(new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(guid,clr,Ptype),3);

sn.SetExtendedProperty(new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(guid,wdt,Ptype),200);

sn.SetExtendedProperty(new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(guid,hgt,Ptype),166);

sn.SetExtendedProperty(new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(guid,lft,Ptype),200);

sn.SetExtendedProperty(new ExtendedPropertyDefinition(guid,Top,Ptype),200);

sn.Subject = "Test Note";

sn.Body = new MessageBody(BodyType,BodyText);

sn.Save(WellKnownFolderName.Notes);

With each new version of Exchange, more and more functionality is being added into EWS. What follows are additional tasks for which EWS is useful. Of course, EWS is a very large topic, so naturally we haven't covered all of it here. Nonetheless, we hope that we have provided you with a good general understanding of EWS.

EWS provides operations to set and get both the OOF status and OOF messages for a particular user. EWS also plays a part in allowing other users to view the OOF status of a group of users using MailTips operations, which are discussed in the next section. Listing 11.21 shows you how to get a user's OOF notification.

Listing 11.21: How to get a user's OOF status using the EWS Managed API

string Mailbox = "user@exchange-d3.com";

OofSettings OofUserSettings = service.GetUserOofSettings(Mailbox);

Console.WriteLine("OOF Status : " + OofUserSettings.State.ToString());

Listing 11.22 shows you how to set a user's OOF status using the EWS Managed API. You should always get the current OOF setting for a user before submitting your modifications.

Listing 11.22: How to set a user's OOF status using the EWS Managed API

String Mailbox = "user@exchange-d3.com"; var OOFState = Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.OofState.Enabled; OofSettings OofUserSettings = service.GetUserOofSettings(Mailbox); OofUserSettings.State = OOFState; service.SetUserOofSettings(Mailbox, OofUserSettings);

MailTips are a relatively new feature of Exchange, introduced in Exchange 2010. They provide the ability to access and present information to a user before they send a message based on the parameters of the message they are about to send. For instance, before a message is sent, you can use MailTips to determine the Out-of-Office status for a particular recipient. They can also be used to flag issues to users before they click Send, thus cutting down on the proliferation of nuisance or accidentally sent email. There are currently no methods available in the EWS Managed API to take advantage of the MailTip operations, but you can use the WSDL strongly typed proxy objects. Listing 11.23 shows you how you can get the Out-of-Office status of a particular user using a MailTip operation.

Listing 11.23: Getting a user's Out-of-Office status using a MailTip

ExchangeServiceBinding esb = new ExchangeServiceBinding();

esb.Credentials = new System.Net.NetworkCredential("uname","password");

esb.Url = service.Url.ToString();

esb.RequestServerVersionValue = new RequestServerVersion();

esb.RequestServerVersionValue.Version = ExchangeVersionType.Exchange2010_SP1;

GetMessageTrackingReportRequestType gmt = new GetMessageTrackingReportRequestType();

GetMailTipsType gmType = new GetMailTipsType();

gmType.MailTipsRequested = new MailTipTypes();

gmType.MailTipsRequested = MailTipTypes.OutOfOfficeMessage;

gmType.Recipients = new EmailAddressType[1];

EmailAddressType rcip = new EmailAddressType();

rcip.EmailAddress = "fsmith@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

gmType.Recipients[0] = rcip;

EmailAddressType sendAs = new EmailAddressType();

sendAs.EmailAddress = "fsmith@exchange-d3.onmicrosoft.com";

gmType.SendingAs = sendAs;

GetMailTipsResponseMessageType gmResponse = esb.GetMailTips(gmType);

if (gmResponse.ResponseClass == ResponseClassType.Success)

{

if (gmResponse.ResponseMessages[0].MailTips.OutOfOffice.ReplyBody.Message != "")

{

//User Out

Console.WriteLine(gmResponse.ResponseMessages[0].MailTips.OutOfOffice.ReplyBody.Message);

}

else

{

//user In

}

}

FreeBusy lookups can be used in a number of different ways in Exchange to build different types of application features. For instance, an In/Out board could show which staff members are currently in a meeting and those who are available. The same idea can also be applied to resources or meeting rooms to show availability across a large number of resources, without the need to query each calendar separately.

The GetUserAvailiblity operation in EWS is what allows you to obtain the FreeBusy information for a user. There are two different levels of information returned from this operation. The first, and least informative, option is pure FreeBusy information. This essentially shows the user's availability in different time slots. If the querying user has the appropriate rights, the second option is a full representation of what the user is doing, covering not only the contents of various time slots but also the subject and location details of any scheduled appointments. Listing 11.24 shows you how to retrieve the FreeBusy information for multiple users.

Listing 11.24: Using EWS to get the FreeBusy status of multiple users

//Set the Start and End time to get the FreeBusy Time for this example the time period for the next 24 hours is used

DateTime StartTime = DateTime.Parse(DateTime.Now.ToString("yyyy-MM-dd 0:00"));

DateTime EndTime = StartTime.AddDays(1);

TimeWindow tmTimeWindow = new TimeWindow(StartTime,EndTime);

//Tell EWS that we want to get the Detailed FreeBusy status

AvailabilityOptions aoOptions = new AvailabilityOptions();

aoOptions.RequestedFreeBusyView = Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.FreeBusyViewType.Detailed;

aoOptions.MeetingDuration = 30;

//Tell EWS which users we want FreeBusy for

List<AttendeeInfo> atAttendeeList = new List<AttendeeInfo>();

atAttendeeList.Add(new AttendeeInfo("user1@exchange-d3.com"));

atAttendeeList.Add(new AttendeeInfo("user2@exchange-d3.com"));

GetUserAvailabilityResults avResponse = service.

GetUserAvailability(atAttendeeList,tmTimeWindow,AvailabilityData.FreeBusy,aoOptions);

Int32 atnCnt = 0;

foreach(AttendeeAvailability avail in avResponse.AttendeesAvailability) {

Console.WriteLine(atAttendeeList[atnCnt].SmtpAddress);

foreach (Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.CalendarEvent calendarItem in avail.CalendarEvents)

{

Console.WriteLine("Free/busy status: " + calendarItem.FreeBusyStatus);

Console.WriteLine("Start time: " + calendarItem.StartTime);

Console.WriteLine("End time: " + calendarItem.EndTime);

Console.WriteLine();

}

atnCnt++;

}

The final example of the application of EWS shows that you can perform all of the delegate permission operations that are available within Outlook. For example, you can enumerate the delegates on a mailbox using the code shown in Listing 11.25.

Listing 11.25: Enumerating the delegates on a mailbox

Mailbox dgDelegateMailbox = new Mailbox("user@exchange-d3.com");

DelegateInformation dgInfo = service.GetDelegates(dgDelegateMailbox,true);

foreach (DelegateUserResponse dgUser in dgInfo.DelegateUserResponses) {

Console.WriteLine(dgUser.DelegateUser.UserId.DisplayName);

Console.WriteLine(dgUser.DelegateUser.Permissions.CalendarFolderPermissionLevel);

}

Listing 11.26 shows you how to add a new delegate. It is important to note in this example that you should obtain the existing user delegate setting for MeetingRequestDeliveryScope, which specifies how meeting-related messages are handled between the delegate and the delegator's mailbox:

Listing 11.26: How to add a new delegate

String Mailbox = "user@exchange-d3.com";

var CalendarPermissions = DelegateFolderPermissionLevel.Editor;

DelegateInformation dgInfo = service.GetDelegates(Mailbox,true);

//Create a New Delegate

DelegateUser newDel = new DelegateUser("user@exchange-d3.com");

//Set the Calendar Permission to Editor for this user

newDel.Permissions.CalendarFolderPermissionLevel = CalendarPermissions;

//This delegate won't receive meeting Invites for the delegator

newDel.ReceiveCopiesOfMeetingMessages = false;

newDel.ViewPrivateItems = true;

//Post the request to the server

service.AddDelegates(Mailbox,dgInfo.MeetingRequestsDeliveryScope,newDel);

Now that you have learned how to use EWS to create Exchange-based applications, in this section we will work with a real-world example of taking a script that was written in VBS using the CDO 1.2 library and converting it to use PowerShell and the EWS Managed API. Recall from earlier in this chapter that in Exchange Server 2013 the available APIs are changing, with libraries like CDO 1.2 being deemphasized and MAPI needing to be encapsulated in RPC over HTTPS.

The following VBS script is one that we wrote a while ago that logs onto a mailbox using CDO 1.2, uses a MAPI filter to find contacts with photos, and then exports those photos to a directory.

The first section of the CDO script creates a dynamic MAPI profile from the mailbox and mailbox server name variables passed in from the command line. Following are the lines of VBS code:

snServername = wscript.arguments(0)

mbMailboxName = wscript.arguments(1)

set csCDOSession = CreateObject("MAPI.Session")

pfProfile = snServername & vbLf & mbMailboxName

csCDOSession.Logon "","",False,True,0,True, pfProfile

In EWS, you don't need a MAPI profile—all you need is the CAS URL for EWS. Thus, instead of passing in the server name of the Mailbox server, Autodiscover is used to get the CAS URL. In EWS/PowerShell, the following code would establish a connection to a CAS server using the currently logged-on credentials. This achieves the same thing as the CDO 1.2 code:

$MailboxName = $args[0]

Add-Type -Path "c:\EWS API\2.0\Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.dll"

$ExchangeVersion = [Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.ExchangeVersion]::Exchange2010_SP2

$service = New-Object Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.ExchangeService($ExchangeVersion)

$service.UseDefaultCredentials =$true

$service.AutodiscoverUrl($MailboxName,{$true})

The next section of the script will establish a connection to the mailbox's Contacts folder. In CDO 1.2, the following code achieves this:

Public Const CdoDefaultFolderContacts = 5 set cntFolder = csCDOSession.getdefaultfolder(CdoDefaultFolderContacts)

In EWS, the following code uses the WellKnownFolderName enumeration to connect to the Contacts folder:

$cntFld = [Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.WellKnownFolderName]::Contacts $folderid= new-object Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.FolderId($cntFld,$MailboxName) $Contacts = [Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.Folder]::Bind($service,$folderid)

The third section of the script filters the contents of the Contacts folder to just those that contain a photo. In CDO 1.2, it does this by creating a MAPI filter on an extended MAPI property, as shown here:

set cfContactscol = cntFolder.messages

set ofConFilter = cfContactscol.Filter

guid = "0420060000000000C000000000000046"

Set cfContFltFld1 = ofConFilter.Fields.Add("0x8015",vbBoolean,true,guid)

In EWS, a search filter is used to limit the items returned by the FindItems operation to just those with attachments, as shown in the following code:

$pidTagHasAttachments = new-object Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.ExtendedPropertyDefi

nition(0x0E1B, [Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.MapiPropertyType]::Boolean)

$sfItemSearchFilter = new-object Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.SearchFilter+IsEqualTo

($pidTagHasAttachments,$true)

$ivItemView = New-Object Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.ItemView(1000)

$fiItems = $null

do{

$fiItems = $service.FindItems($Contacts.Id,$sfItemSearchFilter,$ivItemView)

$ivItemView.Offset += $fiItems.Items.Count

}while($fiItems.MoreAvailable -eq$true)

The fourth section of the script downloads the contact photo attachment. In CDO 1.2, the following code is used to loop though the filtered message collection:

Set objFSO = CreateObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject")

For Each ctContact In cfContactscol

Set collAttachments = ctContact.Attachments

For Each atAttachment In collAttachments

If atAttachment.name = "ContactPicture.jpg" Then

strTempFile = objFSO.GetTempName

strTempFile = Replace(".tmp",".jpg")

atAttachment.WriteToFile("c:\contactpictures\" & strTempFile)

wscript.echo "Exported Picture to : " & strTempFile

End if

next

Next

To do the same thing in the EWS Managed API, first you need to call the LoadPropertiesFromItems method, which will perform a batch GetItem request that will retrieve the details of the attachments on an item. Once this has been completed, the results of the FindItems operation can be enumerated and the attachments can be downloaded to a local directory.

do{

$fiItems =$service.FindItems($Contacts.Id,$ivItemView)

//Create Property Set and define the properties you wish to load

$psPropset= new-object

Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.PropertySet([Microsoft.Exchange.WebServices.Data.BasePropertySet]::FirstClassProperties)

//LoadPropertiesForItems will do a batch GetItems request for the Item Collection [Void]$service.LoadPropertiesForItems($fiItems,$psPropset) foreach($Item in $fiItems.Items){ if($Item.Attachments.Count -gt 0){

#Varible to hold the download directory

$downloadDirectory = "c:\temp\contactpictures"

#Loop through and download each attachment using the Attachment Name

foreach($attach in $Item.Attachments){

if($attach.IsContactPhoto -eq $true){

"Found on Item : " + $Item.Subject

$attach.Load()

$fiFile = new-object System.IO.FileStream(($downloadDirectory + "\" + $item.

Subject + "-" + $attach.Name.ToString()),[System.IO.FileMode]::Create)

$fiFile.Write($attach.Content, 0, $attach.Content.Length)

$fiFile.Close()

}

}

}

}

$ivItemView.Offset += $fiItems.Items.Count

}while($fiItems.MoreAvailable -eq$true)

An exciting new feature in Exchange 2013 is mail apps for Outlook, which replaces both add-ins for Outlook and OWA web forms. This feature allows you to build customized applications with a consistent user interface across Outlook and OWA. This was very difficult to achieve in previous versions of Exchange. Currently, this feature is still in its infancy, so there is a limited subset of functionality at RTM. However, as service packs are released, the feature set is expected to grow toward parity with what is available via Outlook add-ins today. Outlook mail apps are only supported in Outlook 2013 and the Exchange 2013 Outlook Web App. For older versions of Outlook you still need to use Office add-ins to provide customization. If you currently have a custom Office add-in for Outlook, this will still be supported in Outlook 2013. However, any custom Outlook web forms that you have in Exchange 2007 or Exchange 2010 will need to be migrated to a mail app to run with the Exchange 2013 OWA.

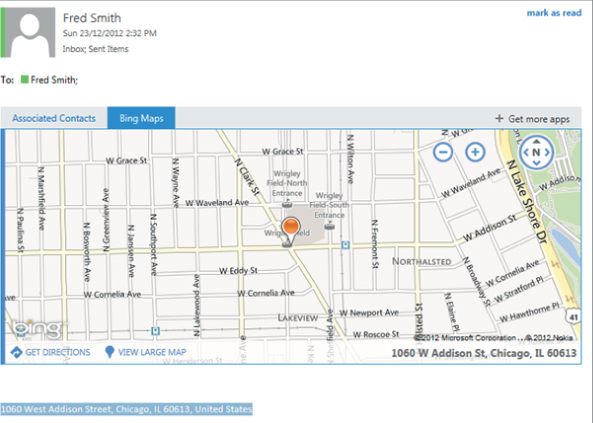

Mail apps display within a special application box in the currently viewed Outlook item, such as an email message, meeting request, meeting response, meeting cancellation, or appointment. Figure 11.2 shows the Bing Maps app displayed within a message in OWA.

Figure 11.2 Bing Maps app showing in-line with a message in OWA

This app is activated when an address is detected within a message. A mail app can be identified and activated based on certain strings, referred to as entities, in the subject and body of the current Outlook 2013 or OWA item. These entities can include addresses, contacts, email addresses, meeting suggestions, phone numbers, task suggestions, and URLs.

Mail apps can call third-party web services, as shown in Figure 11.2, which uses the Bing Maps web service. They can also use EWS to access more information on the current item or other items that are stored within an Exchange mailbox. Mail apps have activation rules that control when they are displayed in messages. For IT professionals, you can think of these activation rules like the Inbox rules that have been around in Exchange since its inception. An activation rule can mean that an app is shown only when mail is received from certain users, with specific text in the subject or body, or is of a particular item type.

Mail apps are built on top of the new Office apps customization framework introduced in Office 2013. Apps can be published to the Office store, Exchange catalog, or other web server. If they are published to the Office store, they can be sold or provided free to a worldwide audience. A permissions framework controls what an app can do, and certain applications can be installed and enabled only by administrators. The ability for users to install and enable third-party mail apps can also be controlled via policies.

A mail app consists of an HTML web page and its associated JavaScript files that are hosted inside the email client. Three email clients offer support for mail apps in Exchange: Outlook 2013, Outlook Web App (OWA), and the Outlook Mobile Web App (Exchange 2013 only). How mail apps execute at runtime differs, depending on the email client you're using. For example, with the Outlook desktop client, the app web page is hosted “out of process” inside a web browser control. Out of process means that the app doesn't run within the Outlook process space. Instead, it runs within a web browser control inside Outlook's apps for the Office runtime process. The advantage of doing it this way is that it provides security and performance isolation for the app's code, which stops a malfunctioning app that affects the operation of Outlook. The app for Office runtime translates the JavaScript API calls and events from the mail app's code into native calls, and it is also responsible for rendering the app's output inside any Exchange item that meets the app's activation criteria. How the application renders and the size of the application box are also controllable using the application's manifest file.

A mail app is installed using the XML manifest file for that particular app, which defines various settings for the mail app. The XML manifest for a mail app contains the following information:

All of the files associated with a mail app need to be hosted on a web server that is accessible by the Exchange 2013 CAS role server.

One of the critical components for mail apps is the JavaScript API for Office, which includes objects, methods, properties, events, and enumerations that can be used in mail apps in Outlook 2013. A mail app's HTML file should reference this file from the Microsoft Content Delivery Network (CDN), accessible at

https://appsforoffice.microsoft.com/lib/1.0/hosted/office.js

Or you can host this file along with your application. For example, your mail application's HTML file would include the following line to load the Office JavaScript API:

<script src="https://appsforoffice.microsoft.com/lib/1.0/hosted/office.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

A three-tiered permission model is used within mail apps that determines what resources a particular mail app can access, what the app is capable of doing, and under what conditions the app will execute. The permission level is configured in the application's manifest file, and if it's not specified, the Restricted permission level is applied. Table 11.3 outlines the three permission levels.

Table 11.3Mail app permission levels

| Permission Level | Permission Details |

| Restricted |

|

| ReadItem |

|

| ReadWriteMailbox |

|

To use Exchange Web Services within a mail app, the application must first request the ReadWriteMailbox permission in the application's manifest file. To make an EWS request, the makeEWSRequestAsync method of the Mailbox class in the JavaScript API for Office is used. As the name implies, the request is made asynchronously and a callback is used to deal with the results. Currently, only a subset of the available EWS operations can be used within mail apps. If you try to use a restricted operation, an error will be returned. Table 11.4 lists the available EWS operations in mail apps.

Table 11.4EWS operations available in mail apps

| Type | Operations |

| Item | GetItem, CopyItem, CreateItem ,MovieItem, SendItem, UpdateItem |

| Folder | CreateFolder, GetFolder, UpdateFolder |

| Search | FindConversation, FindFolder, FindItem |

| Other | MarkAsJunk |

The Exchange development center hosts a number of mail app samples to get you started. As a primer, we suggest, “How to: Create your first mail app for Outlook by using a text editor,” which can be found at: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/fp161148.aspx. This takes you through a fully working example of a mail app.

Installing your mail app is a rather straightforward process. Depending on the permissions required by the application, mail apps can be installed by the user via EAC in Outlook or OWA. Apps that require readItem or ReadWriteMailbox permissions need to be installed by an administrator via the EAC or the EMS using the New-App cmdlet, as shown here:

New-App -URL:"http://<fully-qualified URL">

Mail apps can also be installed from the Microsoft store by users, but these apps can only specify the Restricted permission set.

We will now consider some of the best practices for writing EWS code. The first thing to remember is that EWS operations are just normal web requests/responses. This means that the requests can be run both asynchronously and concurrently in most instances. Thus, this provides a strong framework on which to build high-performance code. When you are architecting your code, try to keep this in mind and resist the urge to write your code in an overly synchronous manner, that is, one where you need continually to go back to the server to retrieve more information.

Here a few tips to follow to keep your EWS code lean and mean:

If you're seeking to integrate searches to Exchange from SharePoint 2013, look into using token authentication, which will avoid the necessity of prompting for user credentials. Also, eDiscovery allows you standardize on using KQL to query both Exchange and SharePoint.

We have spent most of this chapter examining how you can extend Exchange by creating various add-on solutions using Exchange's APIs. There are, however, a wide variety of products already available that will enable you to extend the functionality of Exchange or, at the very least, with which Exchange can integrate in some way. Such products may thus provide solutions that fully meet your or your customer's requirements.