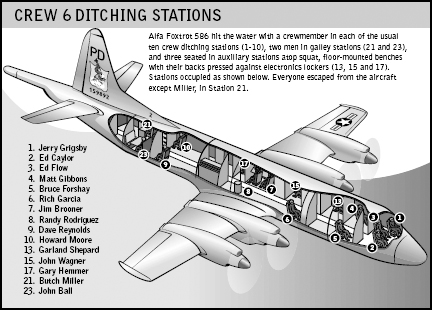

Still high on adrenaline at first, once the thirteen survivors were aboard the rafts and settled down, they looked around and counted themselves in pretty good shape.1 It would take a little time for the razor-sharp cold to slice through clothing and skin, through fat and down to muscle and bone marrow.

Conditions were especially good, by local standards, in the Mark-12. There, atop the inflated, insulating bottom and under the collapsed canopy flapping wildly against the raft’s doubled-decked inflation chambers—the rib assembly that would have held the canopy erect was not in the raft’s equipment kit, it had been removed during routine inspection—each man had almost ten square feet of watery space to himself.

Accommodations in the tiny, overcrowded Mark-7 were much less baronial. The nine in that raft had barely three square feet apiece.2 Once aboard, Ed Flow’s legs stretched the full width of the raft (later, he would lock his knees to keep the two sidewalls from closing in on them). The other eight, all shorter, had scarcely more room in the narrow float. Beneath their legs, in the center of the narrow raft, lay a tangled web of wet nylon shroudlines that kept survival equipment securely tethered to the floor. And no cover; Mark-7s were not equipped with them. The Mark-7 was completely open to the sea, the spray, the wind, and the rain: something to take to the beach, nothing with which to challenge the stormy North Pacific Ocean as winter approached.

They were alive. But the crew’s initial euphoria, fueled by adrenaline and by their successful escape into the rafts, gave way quickly to reality.

AF 586 hit the water with its big fuselage fuel tank (seventeen thousand pounds capacity) empty. But there was as much as twenty tons of JP-4 jet fuel, kerosene, in its nearly full wing tanks, roughly equally divided among the four. In flight, after engine no. 1 was shut down for loiter and at least until the first fire warning, the flight engineer would have been cross-feeding fuel from no. 1’s feed tank to engines 2, 3, and 4, to keep the aircraft balanced and to ease the load on the pilot flying. The no. 3 and 4 tanks, on the starboard side, would have been breached instantly when that wing tore off near the root with the final impact. Tanks 1 and 2, on the port side, almost certainly would have spilled their contents then too, if not before when the nacelles were wrenched from the wing. JP-4 is significantly less dense than cold seawater, and so the tanks’ contents would have floated in long, greasy streaks on the surface until dissipated by rain, waves and evaporation. Thin tendrils of fuel were still visible on the deeply corrugated surface of the sea when X-ray Foxtrot 675 arrived on station more than two hours later.

Several among the crew were temporarily blinded by JP-4 in their eyes or sickened by swallowing it. Caylor had his face pushed into jet fuel pooled in the bottom of the raft while climbing aboard. The raw kerosene filled his eyes, mouth, and ears, briefly blinding and, curiously, deafening him, and making him violently nauseous. Moore, who also must have swallowed more kerosene than most during his swim around the tail, retched for hours in the Mark-12, unable to help with the bailing or with anything else. Wagner drank some unwittingly when he surfaced near the Mark-7, and Gibbons did too, on his way to capture the drifting Mark-12. Gibbons, “puking like a dog,” worried for the next few hours that each upheaval was costing him precious body heat.

Every passing swell broke on top of them, showering the rafts with seawater and forcing constant, ineffective bailing. Rain, a cold horizontal torrent, drenched them when the waves did not. Snow flakes, or maybe it was sleet, speckled the rain. The rafts pitched violently in the enormous seas, in huge, swooping motions that raised or dropped them several times a minute twenty to thirty feet at a time, mixing seasickness with poisoning by ingested or inhaled jet fuel. The Mark-12’s limp cover was blown about by the wind, admitting water and affording little real protection. Almost everyone in Caylor’s Mark-7 would soon be seasick, heaving violently as the raft was tossed around by the waves. Caylor, remarkably, would recover from his nausea even as the others got worse.

They all were exhausted, wet, and terribly cold. Inside the rafts the Pacific Ocean was waist deep, its waters here stained a bright, school bus–yellow by concentrated, leaking dye markers. Its appearance had the men sitting up to their hips in some strange, foam-flecked broth. (Once the dye was bailed out of the rafts, the diluted, colored water would fade to the usual fluorescent chartreuse before losing its tint completely.) Some survivors in the Mark-7 used the space blanket from the raft’s equipment kit to sluice out the seawater in the raft’s bilges. The effort to bail was exhausting and futile. They soon quit trying. Later they would try to use the blanket as a windbreak, and later still as shelter for the dying Brooner from the rain and breaking whitecaps.

Seawater had begun to leak into the anti-exposure suits. Forshay and Rodriguez had large rips in their suits, Forshay in the left arm and Rodriguez in the right leg from hip to thigh, and the seawater flowed freely into them, drenching the men inside. Most of the intact suits, however, eventually admitted water through leaking zippers and seals.3

Finding of Fact. At 1432, X-ray Foxtrot 675, P-3C Ready Alert launched from Adak and was cleared direct to ditch coordinates.

Lt. Patrick Conway, twenty-six, Crew 11’s tactical coordinator, was the mission commander of the Ready Alert crew. Eight years earlier, Pat Conway’s low draft lottery number (thirty-two, even lower than Ed Flow’s) had propelled him into the Navy Reserve Officers Training Corps Unit at Rice University; he had sampled enough of Army life in military high school in Kerrville, Texas.4 In the late summer of 1974 he started training to become a naval flight officer.

In October 1978, Conway was coming to the end of his three-year tour in Patrol Squadron 9. He had been through the transition from P-3Bs to the new P-3Cs, completed two deployments to Okinawa, Japan, and spent time on Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. This was his second trip to Adak. (During his first detachment to the island in midsummer, he had gotten married. His bride, a Navy Supply Corps officer, had flown up from Oakland, California, for the ceremony and returned south a few days later to wait for him.)

Lt. Ronald Price, twenty-seven, was its plane commander. Tall, blond, and good looking, with the wavy hair of a TV anchorman, Price had been a walk-on basketball player as a midshipman second class (junior) at the Naval Academy. Later he would play on all-Navy softball and basketball teams. Price left Annapolis one year ahead of Ed Caylor, for whom he would be searching today. The two men were close friends; they had been in the 10th Company together through three overlapping years at the boat school. Price would leave the Navy in 1979 after his first squadron tour, one year ahead of Caylor, and go to fly for the airlines. Eastern got an excellent pilot, evidenced by the fact that Price had been Patrol Squadron 9’s check airman, responsible for pilot training standardization. It was Price’s tight, illegible signature at the bottom of Jerry Grigsby’s most recent flight evaluation.

Beginning at 9:00 A.M. on the twenty-sixth and for the next twenty-four hours that Crew 11 would have the Ready Duty, Pat Conway’s and Ron Price’s obligation was to get the alert aircraft, PD-9 (Buno. 159890), off Adak and into the air within one hour of an order to fly.

Crew 11 at Adak was one of a number of Ready One P-3 alert crews scattered throughout the world, everywhere there was a maritime patrol squadron or detachment. In their assigned operating areas, these crews were the Navy task group commander’s first response to anything unexpected on or under the surface. Other aircraft and crews would back up the urgent response for as long as necessary.

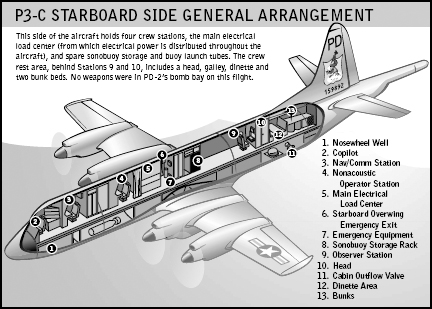

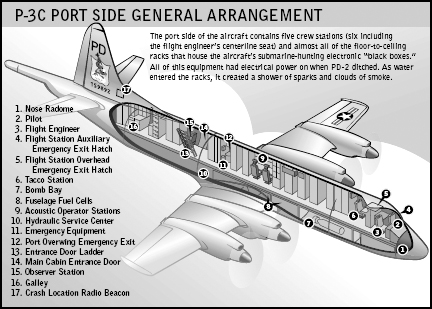

On Adak, and at other remote stations, the Ready One often doubled as the local medical evacuation aircraft, too. Injury or ill health could easily outstrip the medical resources of small dispensaries characteristic of these outposts, and speeding someone to a full service hospital could literally mean the difference between life and death. With two bunk beds in the back, and able to maintain sea level cabin pressure almost to fifteen thousand feet flight altitude, the P-3 made a good (if somewhat slow) air ambulance.

The small Adak detachment could not sustain an aircraft on station for long, even if the det were at full strength. Adak’s was not, but thanks to the P-3’s long legs and Ready One crews elsewhere, Adak could be rapidly augmented from Moffett Field or Barbers Point, or even Misawa, Japan (if the Seventh Fleet commander first agreed to transfer some of his assets back to the Third Fleet).

Augmentation would quickly become necessary. When X-ray Foxtrot 675’s inertials aligned and the aircraft taxied out toward Runway 23 to join AF 586 west of Shemya, the detachment’s flight line became deserted. The third aircraft, PD-8, was at Naval Air Station Barbers Point, Hawaii, completing a training torpedo weapons load with Lt. Cdr. Jim Dvorak’s Crew 12.5

Today, Conway and Price would get XF 675 off the ground in only twenty-six minutes, a performance made possible by the decision to brief on the aircraft, and hastened by obvious urgency. Seconds after he had run onto the aircraft and tuned his high-frequency, long-haul communications radios, Denny Mette heard AF 586’s Mayday call to Elmendorf. The remaining ten minutes of preparations to launch PD-9 were against the soundtrack of Bruce Forshay’s and Matt Gibbons’s cool reports of the deteriorating situation over HF frequency 11,176 KHz.

Hundreds of miles away, the enlisted crewmen in AF 586 were listening to the end of same soundtrack. Gibbons had patched their HF radio communications with Elmendorf into the cabin’s intercom speakers, thinking that morale would be strengthened if everyone in the tube could hear what was going on and knew that help was on the way. Each time Moore heard Gibbons tell Elmendorf they were now ditching, his heart would stop; each time they did not go down, it would start pounding again.

After takeoff, XF 675 climbed quickly to flight level 180 heading west, on course for 52°40' N, 167°25' E, the coordinates Denny had copied from Matt from the HF. Mette estimated it would take Crew 11 just under two hours to get there. Before they got back on the ground at Adak early the next morning, they would have spent ten and a half hours in the air.

In an effort to encourage his squadronmates to hang on, Mette had told Gibbons that XF 675 would be overhead at 4:00 P.M. In fact, Crew 11 would sight the Mark-7 at 4:45, and spot the Mark-12, a quarter mile away, seconds later. By then, the Air Force had been in the area for almost thirty minutes.

Finding of Fact. At 1446 an Air Force C-135, call sign Scone 92, took off from Shemya and was diverted to the area of the ditch.

Unlike the patrol squadron detachment on Adak, 350 nautical miles to the east, Detachment 1 of the 6th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, on Shemya, did not publish a daily flight schedule. Instead, the flight crews and their two RC-135S aircraft (serial numbers 612663 and 612664) from Eielson’s 24th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron sat on the Rock, cocked and ready to go, waiting for a braying klaxon horn that, like a starter’s gun, would release them from the air base to sprint downrange at military power.

Once aloft and in position over the Bering Sea, the crews would spy with some of the world’s most sophisticated sensors on Soviet submarine and intercontinental ballistic missile tests. Their targets were warheads and decoys plunging down into the Klyuchi impact area, midway up the Kamchatka Peninsula, from distant launch sites in the White Sea and at Tyuratam, in Kazakhstan. The forty tons of infrared telescopes and signals intelligence sensors packed into the RC-135S’s commodious cabin were designed to capture data on the performance of the business end of the USSR’s missiles undergoing flight test. This was the super-secret Cobra Ball mission. One goal was to measure Soviet compliance with accords reached at the bilateral Strategic Arms Limitations Talks.

But “the Ball” was more than that. That afternoon, thanks to their aircraft’s unique systems, the crew in the back of Scone 92 would have better information about rescue efforts swirling about the rafts in the water below them than anyone else within thousands of miles. How much of that information could be used without breaching operations security, and how, were questions the first pilot, tactical commander, and airborne mission supervisor would have to answer.

The five Cobra Ball aircraft in the Air Force’s inventory were a precious national intelligence asset, so important that supposedly the five had a higher priority for common parts than did Air Force One, the president’s aircraft at Andrews AFB, near Washington, D.C. The loss of one Cobra Ball aircraft out of Shemya in 1969—with only a single, strangled radio distress call about fuselage vibrations and going on oxygen—was one of the Bering Sea’s enduring mysteries. Thirty-nine men were lost. No sign of aircraft wreckage was ever found. A second RC-135S ran off Shemya’s west runway the same year, no mystery there. In 1978, there were only three left in the fleet (and one of those, 664, would crash and burn landing east on Shemya in 1982, killing six).

In civilian clothes, Carter’s RC-135S would have been a Boeing 707 commercial transport. It was big: fully sixty feet longer, forty-five feet wider, and more than twice as heavy as Grigsby’s P-3. A 707 stuffed full of the best reconnaissance, navigation, and communications technology in America.

Flight crews deployed to Shemya from near Fairbanks, in central Alaska, for two weeks at a time. Cobra Ball crews loved it on the front lines of the cold war. Their conceit was that everyone else in uniform was practicing, but everything the Ball did was for real. Despite the monkish living conditions (crews slept in a bunkroom in the hangar and cooked their own meals) and miserable flying weather around Shemya, the 24th SRS boasted some of the highest personnel retention rates in the U.S. Air Force.

The Shemya alert hangars stood on a low hill overlooking the runway, separated from it by a taxiway with two 90-degree turns. During the island’s long winter, those two sharp, downhill turns were sometimes glazed with ice, slick as an Olympic luge run. Easing the ponderous RC-135S gingerly through the turns while preparing for takeoff, feeling the three-hundred-thousand-pound aircraft drift sideways through first one and then the other, brought anxious moments to the cockpit before the flight had even begun.

No problem on 26 October. The klaxon sounded at approximately 2:35 P.M., signaling a “higher headquarters mission.” The taxiway was wet, but traction was good, and the crew got their aircraft, Scone 92, towed out of the hangar and accelerating down the runway approximately eleven minutes after the horn went off, about an average response. In the cabin behind the cockpit crew, twelve men—the tactical commander, two navigators, electronic warfare officers, a photographer, an electronics technician, and special signals operators—sat in their seats bringing up their gear and thinking about Ivan.6 Today, however, Scone 92’s sophisticated equipment would be used on a not-to-interfere basis during a search and rescue mission.

Capt. Cliff Carter, USAF, hauled Scone 92 off Shemya AFB at 2:46 P.M. He turned northwest and almost immediately flew up into the cloud bands trailing down from the atmospheric low, now roughly two hundred miles north of the island and centered not far from where he was heading. During the next few days, the Aleutian low’s quick easterly movement would progressively close island airfields to aircraft operations, forcing diversions and cancellations and complicating and impeding rescue operations for days. By early next morning, not long after Scone 92 returned to base, crosswinds would close Shemya a second time.

Carter was a second-generation Air Force pilot. His father had flown C-54s in the storied Berlin Airlift. The experience made him practically a charter member of the cold war. Carter senior ultimately retired as a Military Airlift Transport Service command pilot in 1961. The son’s career in the same uniform began in 1972 and would be much shorter: an Air Force ROTC commission from Southwest Texas State University, flight training in Del Rio, Texas, followed by tours with the 82d and 24th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadrons in the Pacific. By January 1980, Cliff Carter would be back home in Texas, in civvies, looking for an airline job.

On 26 October 1978, Carter’s aircraft and crew followed the familiar operational profile for only the first thirty-six minutes of their flight. After takeoff, Scone 92 sped for an orbit position off Kamchatka, where in the back of the aircraft Capt. Alan Feldkamp, the tactical commander, and his electronic warfare officers would ordinarily wait for “an event” to record.

Alan Feldkamp was another of the sons of small-town America who would congregate unexpectedly in the air west of Attu that afternoon. He was a farm boy from Seneca, in northeastern Kansas, hard by the Nebraska line. Like Carter, Feldkamp was an AFROTC graduate from a state university, Kansas State. Unlike Carter, his tour with the 24th SRS in Alaska was not his last in uniform. Feldkamp would spend twenty-two years in the Air Force, retiring in 1993 as a colonel.

At the top of the climb, one of Captain Feldkamp’s EWOs in the back picked up a radio beacon on 8,364 KHz, the marine band emergency frequency. Minutes later, at 3:11 P.M., Lt. Col. Edgar Winklemann, the Det. 1 commander in mission control on Shemya, told the RC-135S crew that a Navy P-3 had ditched west of the island. At 3:22 Winklemann instructed Carter to abort his high-profile mission and diverted Scone 92 to the crash coordinates.7 Winklemann’s decision to send Carter looking for the Navy crew in distress was immediately endorsed by the parent squadron’s commanding officer, Maj. Larry Mitchell, at Eielson AFB. The Soviets would unknowingly get away with a nearly free shot.

Scone 92 was not carrying out-of-area aeronautical charts, so Carter’s two navigators, Capts. Bruce Salvaglio and Gordy Alder, quickly improvised new ones with the required coverage west of the Aleutians. Their route carefully boxed around the two Soviet-owned Komondorski Islands, lying directly between them and the ditching coordinates. After rounding the 25-mile buffer that surrounded the Komondorskis, Scone 92 had a straight shot to the coordinates, 110 miles away. Carter started his descent a short distance down track, to be below the undercast by the time they crossed the ditching coordinates. The “Raven,” signals intelligence, crew in the back of the RC-135S had no direction finding capability on the distress frequency they were monitoring, but by switching between left and right receiver antennas they could make crude guesses about direction. Still improvising feverishly, Scone 92 homed in on AF 586’s emergency beacon as the aircraft dropped down through the cloud layers toward the surface.

The RC-135S would be the first to arrive at the SAR scene and the biggest thing in the air overhead Crew 6’s rafts. After less than two hours in the water, the unexpected sight of a Boeing in Air Force markings orbiting their rafts at low altitude, beneath the first ragged cloud layer at thirteen hundred feet, was a powerful morale booster to the Navy men afloat below.

At 2:54, coincidentally just minutes after Scone 92 took off, the Adak TSC sent out an OPREP-3 PINNACLE message by flash precedence, reporting that AF 586 was down off Shemya and describing the malfunction incorrectly.8 An OPREP-3 is the preformatted “operational report” used to report significant events or incidents involving U.S. military forces worldwide. “Flash” precedence gave this message priority above all other traffic in the Department of Defense communications system at the time, ringing attention-getting bells at command center teleprinters worldwide. Literally an instant after the message was sent, the news was in the hands of duty officers on watch:

Incident. Aircraft emergency ditching.

Commander’s estimate. Aircraft on PARPRO mission had a massive electrical/hydraulic failure and had a controlled ditch. . . .

Details. Time. 270029Z. Location. 5240N/16725E. Narrative. Crew had a controlled ditch near a poss[ible] Soviet ship in area. Crew status unknown. . . . Remarks. Aircraft ditched alongside surface vessel, possibly Soviet. 15 souls on board. 3 liferafts.

Eighteen minutes later, the Joint Chiefs of Staff message center readdressed Adak’s OPREP-3 to the White House, the National Security Agency, the CIA, and the State Department’s Operations Control Center.

The flag word “Pinnacle” in this message’s subject line reflected that Adak thought the loss of the aircraft and crew would have national-level political, military, and media attention. “Pinnacle” sent the message to the top: on receipt it would have been delivered to the Joint Reconnaissance Center in the NMCC. The JRC watch team would automatically relay it to the secretary of defense and the White House Situation Room. The State Department’s liaison officer on the JRC team could have quickly copied it to his department’s operations center on C Street, across the Potomac River. Washington’s subsequent political involvement in this distant event would play an essential part in the rescue of the crew.

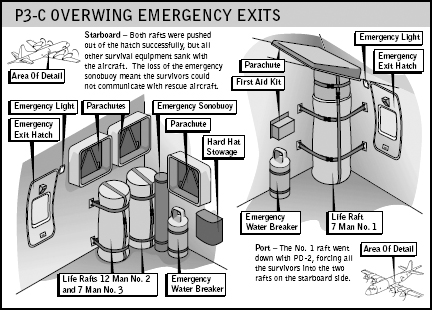

Finding of Fact. Both life rafts were equipped with PRT-5 emergency radios. Only the Mark-12 raft was equipped with a cover. It was not, however, equipped with the cover supports. As a result, both rafts had to be bailed constantly in the high seas.

There were three emergency signal radios stowed aboard AF 586, one in each of its rafts. The small, hand-held URT-33 transmitted only on 243.0 MHz, the UHF distress frequency routinely monitored (“guarded”) by all U.S. military aircraft in flight. It went down with the no. 1 raft. The two, much larger PRT-5s in the second and third rafts transmitted on both UHF military and HF marine distress frequencies. The PRT-5s—replacements for the old World War II–technology, hand-cranked CRT-3A “Gibson girls”—had batteries good for at least three days under ideal conditions but much less in the cold.9

Each raft also contained a survival equipment kit and every man went into the water wearing a nylon survival vest. Together, the kits and the vests gave both rafts a lot of other signaling equipment—water-dye packets, pencil flares, strobe lights, day/night distress markers, a mirror—but not much else. For comfort, the kits contained sunburn ointment and a foil “blanket”; for sustenance, two small cans of drinking water and one “food” packet of coffee-flavored Charms sugar candies and Chiclets gum for each man. With gallons of seawater sloshing around in the rafts and more gallons washing in with every wave, the bailing sponge from the survival equipment kits proved to be no more useful than the sunburn ointment packs. Without a functional canopy to keep the ocean out, even bailing buckets would have been inadequate, and they were not to be had.

Paddles, once a part of the kits, had long since been removed on the reasonable basis that in the open ocean no one would have the stamina to paddle anywhere, which fact made the pocket compass in the kit of doubtful utility, too.

As Jerry Grigsby had approached the Mark-7 in his desperate last attempt at salvation, he had yelled, “Throw the rope.” Ed Flow searched frantically for the heaving line, imagining a long rope with a heavy “monkey’s fist” knot at the end, and then yelled back Jerry Grigsby’s death sentence, probably the last words Jerry ever heard. “We can’t find it,” Flow shouted.

There was no heaving line on the raft. An optional 50 foot nylon line might have been in a raft pocket, but it was unweighted and could not have been thrown successfully into the wind even if found.10 Ed next tried to use their PRT-5 radio, a fifteen-pound packet attached to the raft by its own leash, as a substitute. The hope was Grigsby could grab the floating radio and be hauled in by crewmembers tugging on the line. Flow, kneeling awkwardly on the flexible bottom of the raft and swathed in his inflated life jacket and survival vest, hurled the radio towards Grigsby. It fell into the water five feet short and Grigsby made no attempt to reach out for it. Man and raft quickly floated sixty to seventy feet apart.

This unsuccessful cast from the Mark-7 was not the only use of an emergency radio. Gibbons and Ball in the Mark-12 managed to energize their PRT-5, too. One of the two radios was the source of the repeating SOS signal blanketing the North Pacific on 8,364 KHz that Scone 92 first heard.

U.S. Coast Guard communications stations and the service’s smaller radio stations kept a receiver tuned around the clock to 8,364 KHz. (The frequency, which lay exactly in the middle of the 8 MHz calling band, was also widely guarded in the late 1970s by commercial stations scanning the band, because of its role as the International Lifeboat Frequency.)

When AF 586’s SOS came up on 8,364 MHz, one of the Coast Guard Rescue Coordination Centers could have “tipped” operation of a Pacific-wide high-frequency direction finding (HFDF) net. The net would have fixed the position of the rafts by the intersection of lines of bearing from FAA- and Department of Defense–operated shore stations picking up the emergency signal. HFDF had been perfected during World War II, when the target had been German U-boats on patrol, not mariners in distress, but the North Atlantic and Pacific were still ringed with the big “dinosaur cage” antenna sites because HF intercept and direction finding had an important cold war mission, too.

The net was not activated, however, evidently because AF 586’s position was known. Instead, the Coast Guard’s radio station on Adak and its larger communications station in Honolulu were instructed to transmit a distress broadcast on 500 and 2,182 kilohertz to all ships in range, telling them, “A Navy P-3 aircraft has ditched in position 57-42N 167-29E with 15 P.O.B. [persons on board]. Vessels in the vicinity are requested to assist if possible and contact nearest Coast Guard unit.” The two sites were instructed to repeat the broadcasts every thirty minutes.

A life raft is a tiny object in the ocean, small and low in the water. The (often unsuccessful) search for rafts fills the literature of survival at sea. Thanks to the P-3’s navigation system, to Matt’s and Bruce’s radio reports, and to the arsenal of flares on board the rafts, locating these survivors was not going to be a problem. The rescuers’ challenge would lie not in finding the rafts, but in getting the survivors out of the water in the relatively few hours that spanned ditching and dying of exposure. That would take a ship.

Finding of Fact. Coast Guard Cutter Jarvis, after refueling at Adak, had gotten under way at 1538.

The Rescue Coordination Center at Juneau knew what was important. The survivors had to be plucked out of the water quickly, or they would die.

USCGC Jarvis was alongside the fuel pier at Sweeper Cove, Adak, on its mid-patrol break when Juneau directed the ship to proceed immediately west of Attu, to assist in the search for AF 586 and its crew. When Jarvis was ordered back to sea, AF 586’s first Mayday call to Elmendorf was only eighteen minutes old. The cutter’s commanding officer, Capt. Axel Hagstrom, the team at Adak’s fuel piers, and the crew of YTB-783 (Redwing, a Navy harbor tugboat in the cove) would have the ship refueled and under way, with its amphibious HH-52 helicopter back aboard, in less than ninety minutes. It took special courage to fly the single-engined Sikorsky helicopter in the Aleutians, but as it turned out Jarvis’s aircraft would not participate in the rescue.11

Twenty minutes before AF 586 hit the water, the SAR coordinator at Adak had already asked the AMVER computer in Washington for any vessel in the area of 52°27' N, 166°00' E.12 Soon, this would be refined to a request for information on all ships within three hundred miles of AF 578’s impact point. After a few tries (the initial queries drew blanks), the Coast Guard had a list of fourteen vessels, with an estimated position, course, and speed for each. The closest was Mikasa, supposedly only fifty-seven miles away; the most distant inside of the three-hundred-mile search criterion were Kapitan Bondarenko and Asia Maru, both just off the Siberian Coast and a few miles apart. A Soviet fishing vessel, Mys Sinyavin, was inside the circle, but its last position, almost exactly twenty-four hours old when AF 586 ditched, was 20 miles west of Attu and 190 miles away from AF 586’s splash point. Perhaps for that reason, Sinyavin attracted no special attention from Juneau.13 At about the same time, the commander of the U.S. Third Fleet advised that he had no ships in the area.

By U.S. Coast Guard standards, and the standards of most navies of the world then (and now) Jarvis was a big, new ship: 378 feet long with a crew of 21 officers and nearly 160 enlisted men. It, like its eleven sister ships in the Hamilton-class of high-endurance cutters, was among the capital ships of the U.S. Coast Guard. Aptly in view of the Alaska patrol mission, its namesake was Capt. David H. Jarvis, USCG, who had spent much of his career in the Bering Sea.14

The Jarvis was barely six years old when it was called out for this rescue mission. It had been commissioned in August 1972, the first Coast Guard vessel to enter into active service from the Hawaiian Islands. (That distinction carried with it no special luck. Three months later, Jarvis ran aground with its commissioning crew and suffered major damage. It was the only grounding among the five Coast Guard cutter accidents that year.)

Under good conditions, Jarvis’s two 18,000-horsepower gas turbine engines could push the ship along at a sustained speed of about twenty-nine knots, but during the last few days of October 1978, conditions were terrible. In pounding seas and low visibility, at times Jarvis would make less than four knots toward the ditching coordinates, no faster than the speed of a short man jogging.

Approaching Buldir Island (52°21' N, 175°57' E), roughly halfway from Adak to the ditch site, Jarvis had already pushed through forty-foot seas for half a day, in the face of sustained fifty-knot winds.15 Now, abeam Buldir, Jarvis would report seas fifty feet high and wind gusts as high as seventy-five knots in its fifth progress report to Juneau. In such monstrous seas, hull down in the trough between two waves, Jarvis’s bridge on the 03 level (three decks above the main deck) would have been almost level with the crest of the foaming rollers breaking to either side.

The cutter would not arrive at the SAR site until more than two days had passed. In view of the time-late on station and the departure of Sinyavin, the deployment of Jarvis to the site turned out to be more of a gesture than a real contribution to the search and rescue effort. Without a raft, survival in an anti-exposure suit supported by only a life preserver probably would have been possible only for a few hours. Even in a raft, eighteen hours would have been a very long time to endure the killing cold.

Finding of Fact. At 1540, Scone 92 established communications with X-ray Foxtrot 675 on Shemya Tower frequency and coordinated search intentions. Scone 92 was monitoring the emergency beacon (frequency 8,364), but had no direction finding capabilities.

A little over an hour into XF 675’s sprint to the SAR scene, Denny Mette refined his arrival estimate: Crew 11 would get to AF 586’s ditching coordinates at 4:24. At cruise altitude, moving fast and more than halfway there, Mette overheard Scone 92 reporting an estimate of 4:10 into the area. The P-3 would be entering the scene from the east, the RC-135S more from the north.

His cockpit promptly passed UHF direction finding information to the Air Force crew, thinking wrongly that PD-2’s Channel 15 emergency buoy had made it out of the aircraft and was in the water marking the rescue datum. No matter. Scone 92 did not have a receiver aboard that could home on 345.5 MHz.

Finding of Fact. At 1610 Scone 92 arrived in the S.A.R. area and commenced a rectangular search pattern at 1,200–1,800 feet, remaining below clouds.

In similar circumstances, overhead an SAR datum in the open ocean, a World War II flight crew would have resorted to an expanding square search, with the first leg into the wind, everyone aboard peering out at the turbulent water passing swiftly beneath him while the aircraft flew a pattern that loosely resembled a Greek key.

Scone 92, the last word in operational signals intelligence and electro-optics technology of the late 1970s, did something similar.

Bruce Savaglio had once attended a seminar on search and rescue at Mather AFB, and his recollections were all anyone aboard knew about the subject. Coached by Savaglio, at the nav 1 station just behind the copilot, Carter rolled into a circular visual search pattern, a slowly opening clockwise spiral centered on where AF 586 went down. In the cockpit Carter and his copilot had to work hard at this unfamiliar altitude: the RC-135S’s right hydraulic system had failed during their flight, eliminating power boost to the rudder, so they hand tooled the aircraft. At 220–230 knots, flaps up, whipping around over the waves like a pylon racer in some x-games airshow. In the back, the tactical crew, clustered on the starboard side of the aircraft, stared out the three side windows, searching for survivors.16

Finding of Fact. At 1617, Scone 92 sighted a flare and identified a raft at position 52°34' North 167°31' East. On succeeding passes, they identified the second life raft, and passed this information on to X-ray Foxtrot 675, that was still en route to the area. No aircraft or visual wreckage was sighted at any time.

Only seven minutes after starting to look, Scone 92 found the rafts. Carter’s copilot, Capt. Bob Rivas, was first to see a flare rising from the water just to the right of the nose, two miles away. Rivas, famously quiet and unassuming, did not break out of character. His announcement, “There it is,” meaning the survivors’ raft, was almost inaudible. Soon, green smoke rising from one of the rafts acknowledged that the aircraft had been seen, too. During the next twenty minutes, they would spot each raft two more times, losing sight of it on each pass and regaining it on the next.

In Scone 92’s cockpit, Rivas took everything he was seeing in stride, but one of the Ravens in the back did not. Capt. Greg Cummins, a graduate of the Air Force Academy and jump school, bravely—recklessly—proposed to put on a chute and drop into the water to help the men in the rafts. If Cummins had gotten out of the aircraft alive, he would have almost certainly drowned on water entry, entangled in shroud lines or dragged by the canopy, or died of exposure soon thereafter. Happily a cooler head, Feldkamp, restrained him.

In the rafts, the sight of the RC-135S overhead was like a tonic, a powerful stimulant. Ball, in the Mark-12, grinned at Gibbons and started chanting “Sky King, Sky King.” Everyone now optimistically looked forward to pickup.

Finding of Fact. At approximately 1640, X-ray Foxtrot 675 relieved Scone 92 as primary S.A.R. aircraft over the survivors. X-ray Foxtrot 675 descended to 500 feet and Scone 92 climbed to 34,000 feet to assume a radio relay role.

Boeing’s 707 transport was designed for economical, high-speed cruising in the lean atmosphere above thirty thousand feet. High altitude was the RC-135S’s natural element, too. With the aircraft down under thirteen hundred feet, and often as low as five hundred, and maneuvering hard, Scone 92’s four Pratt and Whitney TF-33 turbofan engines were sucking down fuel greedily while they hauled the big aircraft in tight circles around the two rafts at 220 knots.

Just after 4:30, Carter told the inbound Navy aircraft that he was getting low on fuel and needed to climb. (The two had started talking to each other at 3:40, after XF 675 crossed the midpoint on the way to the SAR scene and while Scone 92 was still en route to the site.) The first attempted altitude swap was aborted as they closed on each other in the clouds. When XF 675 marked overhead the survivors a few minutes later and actually got a glimpse through the cloud layers of the RC-135S heading the other way, Scone 92 began his climb to 34,000 feet and XF 675 continued his descent. Level at five hundred feet, XF 675 took over as the on-scene commander for the rescue that was now beginning its third hour.

The survivors’ elation at having been found so quickly did not last long. Conditions in the rafts were too grim to support lighthearted optimism. In the Mark-7, Forshay noticed depression settling back down upon them soon after Scone 92 appeared. Their mood was not even lightened when PD-9 suddenly materialized beneath the clouds accompanied by the familiar growl of its T-56 turboprop engines, to replace the RC-135S overhead.

For the next three hours, Carter and his crew would remain at altitude, relaying communications between Elmendorf and Yokota, XF 675 on station, and the aircraft coming to join him. The aircraft’s prototype UHF satellite communications suite at the tactical commander’s station, a one-of-a-kind UYA 7 system, meant that Scone 92’s comms had even greater reach than the old technology, high-frequency radios on board either XF 675 or CG 1500. From high overhead, Capt. Alan Feldkamp, the Air Force crew’s tactical commander, could describe the events below him in a blow-by-blow radio teletype commentary reaching far beyond Shemya. Beyond SAC’s Strategic Reconnaissance Center in Omaha, and all the way to the Joint Reconnaissance Center and the National Security Agency, in Washington, more than five thousand miles away. To any headquarters that had the equipment to eavesdrop on Feldkamp’s messages to Winkleman. Back on the same circuit came a question from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “Is the aircraft still afloat?” General Jones himself wanted to know.17 “No,” Feldkamp typed in, “it’s not.”

Later, Carter would break away hurriedly to refuel from Scone 93, a KC-135 tanker launched off strip alert at Eielson to support him, and then return to the area for another two hours of communications relay before heading back to Shemya and a landing at 10:00 P.M. Theirs had been a great flight. Carter’s and Feldkamp’s postflight report to the parent squadron and wing concluded, “The sense of kinship with the downed crew members and exhilaration of that first flare was felt by every man on board and was the greatest ‘gaslight’ we will ever call.”18

In early April 1980, every man aboard Scone 92 was awarded the Air Medal for “meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight” on 26 October 1978. Cobra Ball crews got many such medals. The award was Carter’s second and Feldkamp’s fourth.

Finding of Fact. At approximately 1645, X-ray Foxtrot 675 sighted both rafts, one with an estimated six survivors and the second with one visible survivor. The crew dropped smoke markers and sonobuoys to mark the rafts. Wind conditions, high sea state and poor visibility made it extremely difficult to keep the rafts continually in sight, much less to accurately determine the correct number of personnel aboard.

The wind had died down slightly. It was still out of the southwest, but now blowing around thirty knots, occasionally gusting higher. Conway had quickly abandoned the use of smoke markers. The spume blowing across the tops of the waves was so heavy that the markers’ dense, white plumes of smoke quickly became invisible against the background foam or lost in the rain. Sonobuoys made better placeholders. As the wind pushed the rafts away from one buoy, another buoy would be dropped, and tracked with the on top position indicator, until that buoy, too, had to be replaced.

During the next four hours, Price and the cockpit crew drove XF 675 around a racetrack pattern less than five hundred feet above the two rafts, trying to keep both of them in sight on each pass. The rafts continue to drift apart, and on some passes the crew lost sight of one or the other.

Pinned to this pattern by fear of losing sight of the rafts, the crew aboard XF 675 knew that they were not providing real help to the desperate men passing beneath their wing every few minutes.

Finding of Fact. At 1713, Coast Guard 1500, the C-130, landed at Naval Station Adak for refueling and briefing.

Eight hours after he had left, Bill Porter was back on the ground at Adak, parking Coast Guard 1500 alongside a fuel truck. His crew was there just long enough to brief, refuel, and pick up some food. They were not even halfway through what would eventually become a twenty-three-hour duty day, during which they would log 17.3 hours of flight time.

Naval Station Adak was familiar to anyone from Kodiak, but Porter was more at home with the Navy than most Coast Guardsmen. He had spent six years in the service. In the 1960s and 1970s, Coast Guard aviators got their pilot’s wings the same place Navy and Marine Corps officers did, at Navy flight training facilities in Florida and Texas, but Porter had gone through pilot training as a Navy Aviation Officer Candidate. After he got his wings in October 1969, Porter had two tours of duty as a Navy officer.

The first was flying Guam-based C-130Qs, towing a long antenna out the back of the aircraft. Their important, deadly dull mission was providing emergency “connectivity” (communications in the form of emergency action messages, EAMs) to ballistic missile submarines on patrol in the Pacific. Flying the 130Qs in a tight orbit, such that the mile or more of antenna they streamed stood vertically took a nice touch on the controls, airmanship that was never recognized by aviators whose business was shooting things down or blowing them up.

His next tour was as a multiengine flight instructor in Corpus Christi, Texas, flying two students at a time in antiquated Grumman TS-2 “Trackers.” Porter left the Navy as a lieutenant in 1974. Two years later, he was back in uniform and a Coast Guard lieutenant (junior grade), flying C-130s out of Coast Guard Air Station Kodiak, Alaska. At the end of October 1978, Porter had almost two thousand pilot hours in the C-130 and nearly fifteen hundred in other types of aircraft.

Lt. (jg) Rick Holzshu, his copilot, had a similar history. Holzshu had been an Air Force C-130 pilot before accepting a commission in the Coast Guard. Between them, the two Coast Guard jaygees had years of experience in the boxy airplane they would drive to the SAR datum that evening.

Finding of Fact. Personnel in both rafts assisted the S.A.R. aircraft by utilizing all signaling devices on a regular, continual basis.

Every man’s survival vest contained a pencil flare gun and seven signal cartridges, and each vest also carried two double-ended “marine smoke and illumination” signals. Extras were stowed in the rafts’ equipment kits. The flare gun, a pen-sized “Saturday night special” with a spring-loaded firing pin, fired a tracer round into the air. The longer lasting signal had a twenty-second flare at one end, for night use, and a twenty-second smoke at the other for use in the day.

Soon after Crew 6 went into the water, the men’s metabolic fires began quite literally to cool from the normal 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). Basted in cold water and blown by a cold wind, even beneath the temporary protection of their anti-exposure suits, body temperatures began slowly to creep down. One of the first effects of the chilling was the loss of fine motor coordination as vasoconstriction reduced blood flow to their bodies’ periphery by up to 90 percent. This first, automatic process of heat conservation gave up exactly the sort of manipulation necessary to fire pencil flares and ignite the larger day-night signal markers. Pencil flare cartridges had to be screwed into position one at a time with the firing pin cocked. The signals were fired by working a pull ring akin to a drink can’s pop top.

Forshay found it very difficult to get to his signals because of numb hands and the small zippers on the vest. A few feet away, John Wagner took ten to fifteen minutes to pry his strobe light (a cigarette pack–sized light that flashes forty to sixty times per minute, with an eight-hour life) out of his vest for the same reason. The others had similar experiences.

The four in the Mark-12 raft alternated duties between constant bailing and occasional signaling. John Ball remembered the numbing sequence as “bail for a while, wave at the aircraft for a while.” Eventually, Gibbons’s hands grew so cold that he loaded the pencil flare gun by holding the small cartridges in his mouth and spinning the projector between his stiff hands onto their screw-in bases. In the Mark-7, Shepard was doing the same thing. Shepard had given one mitten away, but both his hands were equally stiff, like fins or flippers. Forshay did it, too. Caylor reloaded his flare gun once the same way also, screwing the live round between his teeth slowly into the cocked launcher as the others were doing, risking firing a tracer round through his mouth and into the back of his head.

Finding of Fact. Misunderstanding concerning the employment of Scone 92 developed at Adak. It was believed that Scone 92 was searching the area for ships, when, in fact, he was at high altitude due to fuel considerations.

Once XF 675 assumed the role of on-scene SAR coordinator, Pat Conway asked Scone 92, then probably well into its climb, to attempt to locate a surface ship, but he was told that they could not. (Det. 1’s postflight report told their parent wing that Scone 92’s navigation radar had been malfunctioning, so a radar search could not be done.) Somehow, this negative response was misunderstood by XF 675 and the Adak TSC, where the logbook has Scone 92 refueled and looking for surface ships. In fact, there were only two American aircraft in the area and neither one was looking for a surface ship.

Despite Crew 6’s care to ditch near one, and Gibbon’s notice to Elmendorf (“preparing to ditch at this time, this position. We’re about ten miles from a ship”) it would be five hours after the ditching before a rescue aircraft deliberately went to find a ship.

In the meanwhile, scouring local waters for help, Juneau asked four vessels, by name, to assist. These four included a South Korean fishing vessel, the motor vessel Hanwoo, the now-familiar tanker Mikasa, and two Soviet naval auxiliaries. The two, Sadir and Sakhalin, were not in the AMVER database but thought to be somewhere in the area by intelligence officers at U.S. Third Fleet headquarters.

Hanwoo declined repeated requests to help, saying that it had insufficient fuel. The 17th Coast Guard District immediately reported the ship’s refusal—a violation of the international law of the sea that requires assistance to mariners in distress—to the Coast Guard commandant.19 The delinquency report was also passed to the Department of State. Mikasa proved to be too far away, and the presence and positions of Sadir and Sakhalin were never confirmed.

Nothing would come from thirteen of the fourteen AMVER contacts.

Finding of Fact. At 1810, Coast Guard 1500 departed Naval Station Adak for the S.A.R. site.

Bill Porter and his crew were off Adak after less than an hour on the ground and just nine hours after they had first left the same place that morning. With full wing and external tanks, loaded with almost sixty-three thousand pounds of jet fuel, their aircraft was good for another fourteen hours in the air. The crew had already put in one full working day. There was no telling how much more they were good for.

Finding of Fact. At approximately 1915, X-ray Foxtrot 675 dropped the S.A.R. kit (consisting of two rafts and an equipment package) to the upwind raft, the Mark-12. The drop was extremely accurate, landing very close to the raft. The survivors were observed to have the ropes holding the rafts to the equipment container. The S.A.R. kit was dropped upwind of both rafts so that if the first raft could not pick it up, perhaps the second could.

The drop had to be “extremely accurate.” Under these sea conditions, even a very small error would have meant that the kit would fall away, forever out of reach. Crew 11 reviewed and rehearsed SAR kit drop procedures several times during their high-speed transit from Adak. The unusual procedure, which requires slow flight at low altitude with three crewmembers clustered around an open main cabin door, fills its own part in Section IX (“Flight Crew Coordination”) of the flight manual. On station, Price flew several bumpy practice passes at low altitude. The powerful winds at flight level prompted him to add thirty knots to the flight manual’s kit drop airspeed.

The tempest blowing past PD-9’s open cabin door, into which they would launch the kit, would be moving at 160 knots (185 mph), the equivalent of a very powerful category 5 hurricane. The procedure, a slow crosswind pass overhead the survivors followed by a right 90-degree, left 270-degree turn for the drop, is designed to put the kit down 50–150 feet directly upwind of the men in the water, without risking the two crew members who will push it out the door or the drop master who will supervise and coordinate with the cockpit.20 Few crews practice the procedure and fewer still have ever performed it.

Three hours after Crew 11 first spotted the Mark-7, Mette at the nav/comm station got a call from Yokota on HF. Someone at Headquarters, U.S. Forces Japan, had done some research, and thought there were two South Korean vessels in their area. Yokota helpfully passed the crew their international radio call signs (6MBT and 6NLX) and the radio frequency to raise them on, 2,183 KHz. Mette acknowledged and called the ships. No response. Less helpfully, Yokota now suggested to the crew of a Navy patrol plane that they fly their aircraft across the bow of any ship they find, to direct them to the search area. Not done yet, the headquarters wanted to be kept informed. Yokota’s repeated, insistent radio requests for “status” information during the night finally provoked the crew to stop answering their calls.21

Conway and Price decided to drop the SAR kit before dark, reasoning correctly that it would be unconscionable to return to Adak with it and impossible to drop it accurately after nightfall. Conway acted as the drop master with a salty chief petty officer standing by, survival knife unsheathed, to cut someone loose in case any lines tangled on the way out the door.

Their target was the Mark-12, where no visible signs of life suggested that this group of survivors was worse off than the crew of the Mark-7.

Finding of Fact. The S.A.R. equipment package could not be taken into the Mark-12 raft because it was too heavy to lift. It, along with one of the S.A.R. kit rafts, was tied alongside the Mark 12 raft.

Crew 11’s SAR kit drop was perfect, so close as to have frightened some of the men in the target raft. The kit’s two rafts drifted downwind—“blowing around like kites,” Reynolds said—to straddle Matt Gibbons’s Mark-12 with the equipment package in between them. Sadly, the men in the Mark-12 could not exploit XF 675’s perfect drop of their SAR kit. Matt Gibbons said they could not get the package into their raft because “of its weight and their weakened condition.” Instead, they tied the kit alongside “for possible future use.” Their condition would have progressively grown worse and it is unlikely that the kit would have ever been used.

One mile or so downwind, a few of the men in the Mark-7 raft saw the kit fall away from PD-9, knowing that they needed it more than the men in the Mark-12. Later, CG 1500 would make an equipment drop of its own, in the dark from two hundred feet on a light in the water. PO Darryl Horning, squatting in the back of the aircraft beside the C-130’s huge, open cargo ramp, would be the drop master. He pushed out a complete MA-2 kit, which included two twenty-man rafts and miscellaneous survival equipment, all roped together.22 The equipment kit plunged into the dark ocean, drifted off and eventually sank unseen, taking a valuable two-way radio down with it.

Scone 92 would be the only aircraft overhead that did not drop survival equipment to the crew. The Boeing had flares and rafts on board, which contained two-way radios, but nothing was dropped during the relatively brief period the aircraft was alone at low altitude. Under these weather conditions, precision bombing with a raft by an RC-135S could not have been successful. Moreover, dropping a raft from a –135 had never been done before, and there was some concern that a raft coming out the aircraft escape chute would wipe out the horizontal stabilizer on its way down.

Finding of Fact. X-ray Foxtrot 675 refused to leave the S.A.R. datum to search for possible rescue vessels until relieved by Coast Guard 1500. The crew was fearful of permanently losing sight of the survivors because of the sea state and poor visibility.

Once the SAR kit was dropped, Price eased PD-9 back up a few hundred feet and pushed the power levers up for maneuver airspeed, around 190 knots with wing flaps partially extended.

At very low altitude and often in tight turns and a high bank angle, XF 675’s radar had a tiny horizon. Most of Sensor Station 3’s scope was flooded out by the bright, fluorescent bloom of sea return, radar energy returning to the receiver from the faces of waves below. The P-3 is designed to search areas of thousands of square miles. But right then, Crew 11 did not know what was ten miles away, or if there was anything there at all.

Finding of Fact. At 1938, Coast Guard 1500 arrived on scene and assumed on station commander. X-ray Foxtrot 675 climbed off station to commence search for a rescue vessel.

Coast Guard 1500 arrived on station after sunset. Down in the Mark-7, Garland Shepard could occasionally see a silvery fluorescence in the water, as tiny glowing marine organisms were raised by the wave crests and dashed into the raft.

The two aircraft carefully coordinated their swap. In poor weather and low visibility, with two aircraft intently focused on a set of coordinates, there is a real danger of midair collision. It has happened.23 Normally aircraft swap procedures, replacing one crew at a datum by another, are carefully defined in exercise operation orders. In this case, obviously, there was no operation order. Price and Porter did not expect to be meeting at 52°40' N, 167°25' E after dark and had not planned on it. Everything was ad hoc. Cockpit chatter resulted in a quickly improvised procedure to keep their aircraft safely apart.

Three hours ago, XF 675 had asked Scone 92 for a radar surface search, and been informed that one could not be done. Bill Porter’s arrival and assumption of the responsibility of on-scene commander freed Price from his frustrating tail chase, and released XF 675 to climb for increased radar range and conduct its own search for a vessel.

Finding of Fact. At 1955, XF 675 held a surface ship in radar contact approximately 30 nautical miles southwest of the liferafts.

There would be no survivors if the men in the rafts were not soon removed from the sea. Even if the abortive equipment drops were completely successful, their effect on longevity would likely have been very small, unlikely to extend anyone’s life past the end of the next day, 27 October. As it was, in the early night hours Ed Caylor would reconsider his private estimate of survival time. His goal had been noon, Friday; now he just hoped to hold on until dawn. Afloat in the other raft, with an estimated gallon of cold water filling each leg of his suit, Gibbons thought that he might make it to morning but no longer. It is likely that all the other survivors saw sunrise as a milestone, too. (In an October 1996 letter to Aviation Week & Space Technology, Caylor wrote he could have survived for only another hour past their rescue.)

Approaching six hours in the water, and now in complete darkness, the men were just a few hours away from starting to slip individually over the edge of a biological cliff, body core temperatures below 30 degrees C. No aircraft on station could do anything about that, but one preparing to come could. Air Force Rescue 65825, an HC-130 aircraft from the 71st Air Rescue and Recovery Squadron, will leave Elmendorf AFB at 8:44 P.M. with two H-3 helicopters in trail, heading west.24

His twin-engine H-3 helicopters, call signs Rescue 804 and 805, are the answer. The two powerful Sikorskys carry famously hardy pararescue jumpers aboard, “PJs,” men who will drop into the open ocean even under these conditions and get Crew 6 hoisted up, flown out, and delivered to medical attention. Unrefueled, the H-3 helicopters cannot get much more than two hundred miles from shore, less probably in today’s weather conditions, but with the HC-130’s tanker support, the mission out to the ditch site and back becomes possible. The plan is that the flight will proceed first to Dutch Harbor, halfway out the Aleutians on Unalaska Island, and then on to Shemya, the stage for the rescue leg of the long flight.

But the big mother ship (the same type as CG 1500 and 1600) and its helicopters never actually get to the SAR area that night. Between 7:30 and 9:10 P.M., Rescue 65825 talks to Scone 92 on HF, getting information on the status of the search while heading west. The next time Rescue 65825 appears in a mission report, it will be 3:50 A.M., talking to Adak Tower. En route from a diversion at Shemya because of crosswinds, 65825 is now diverting from Adak to Cold Bay with his helos because of high winds and turbulence. When their night is over, the three aircraft will have shuttled from Anchorage to Shemya via Dutch Harbor, and back to Cold Bay, 170 miles east of Dutch Harbor, nearly two times the length of the island chain, to no purpose.25 Juneau will release the two H-3s from this mission and back to Elmendorf and normal operations early Friday morning.

The sky and sea are dark now, a thick, velvety blackness that gives way reluctantly to the survivors’ signals. At datum under layered cloud cover, a pencil flare occasionally arcs brightly into the sky, soliciting aircrew attention. The surface of the water around the rafts is speckled with a field of flickering lights, colored strobes, sonobuoy lights, and the glitter of a few marine flares that XF 675 has dropped. At one time or another, confused by what they see, observers in all three aircraft overhead will believe that there are not two but three rafts in the water. That erroneous count will be reported to Adak, Kodiak, and Coast Guard district headquarters in Juneau, and repeated in news media reports. Days later, Jarvis will come upon Gibbons’s empty Mark-12, and it will be identified and reported to Juneau as the apocryphal “third raft.”

Scone 92 calls, relaying a Sky King message. XF 675 and CG 1500 are instructed to light up their aircraft because of possible surface vessels in the area. The word from on high must have had a source in the Soviet Union, but no one on station knows that.

X-ray Foxtrot 675’s blip on Sensor 3’s radar display at 250°/thirty-seven miles is the downed crew’s only hope.

When XF 675 gets his radar surface contact, Coast Guard Cutter Jarvis has been under way only four hours; it is estimating another forty-three hours en route and, in fact, will not arrive at the closest (northeast) edge of the SAR search area for another two full days.

Finding of Fact. At 2014, Coast Guard 1600 departed Elmendorf en route for Shemya to assist in the S.A.R. effort.

It is 1,266 miles from Elmendorf out the island chain to Shemya, about five hours into the wind at cruise speed for a C-130. No one at the Kodiak Rescue Coordination Center or at the Adak TSC knows how long he will need aircraft at the SAR scene. The Coast Guard has wisely begun repositioning relief aircraft and crews, to be able to sustain the effort underway west of Shemya indefinitely. The Navy has, too. Two P-3s will take off for Adak during the night and early morning from Barbers Point and Moffett Field. A second from Moffett Field will follow a few hours later.

CG 1600 has left Anchorage behind, heading west toward the end of the Aleutians and into the deteriorating weather. The aircraft takes off with two crews aboard. Lt. Cdr. John Power’s flight crew will bring the aircraft in; the other crew, Lt. (jg) Al Delgarbino’s, will be available to turn CG 1600 around and fly on a mission out of Shemya immediately. En route, hearing Shemya’s current and forecast weather, CG 1600 diverts to Adak and lands at 3:09.

At Adak, a new Ready Alert aircrew has been patched together by the detachment and sent to barracks for crew rest. The crew will be in the TSC briefing at 2:09 A.M., 27 October, and will take off in PD-9 at 3:24 to replace XF 675 on station. Moments after they leave, Adak will set Storm Condition I and batten down for high winds.

CG 1600 will refuel and then sit chained to the deck at Adak for hours, waiting for better weather. Finally, at 7:38, CG 1600 will get the break its crew has been waiting for and take off, heading directly to the SAR station.

Finding of Fact. Between 2015 and 2036, XF 675 made numerous low fly-overs and fly-bys of the surface vessel (Mys Sinyavin) while signaling with their landing lights. They had no means of communicating via voice. They flashed the letters C-E-F in international Morse Code, which means “aircraft in the water—follow me.” The Sinyavin did acknowledge their signal with a searchlight and turned toward the S.A.R. area.

The Sinyavin already had its powerful bridge searchlight on when XF 675 came upon it. Even under deck lights alone, the big trawler—nearly three hundred feet long, with its distinctive superstructure, cluttered deck, and tall kingposts aft supporting heavy trawl-handling gear—would have been easy to spot at the end of XF 675’s radar run-in to the surface contact.

When XF 675 arrived on top of Mys Sinyavin at 8:15, the ship was already heading northeast, steaming as instructed for 52°40' N, 167°26' E, generally toward the rafts. One of the larger vessels on the fishing grounds, Sinyavin was seven years old at the time of the rescue. It had been built in distant Nikolayev, in the Ukraine on the Black Sea, in 1971.26 Evidently, the plan was that Sinyavin would join the Pacific fishing fleet, because the vessel was named after a small cape on Sakhalin Island’s southeast coast. In late 1978, the crew included twenty-seven officers, ninety men, and eleven women, who cooked and cleaned, a sort of floating household staff. Capt. Aleksandr Arbuzov, the ship’s master, had been in command for the past four years.

The Sinyavin never saw AF 586 go down; it had been unknowingly opening the distance to the rafts since Grigsby hit the water more than five hours ago. Until contacted by radio from Vladivostok at around 7:00 P.M., Aleutian time, Sinyavin had been going in the other direction, for Korsakov, a port in the bight on the southern end of Sakhalin Island. It had finished fishing in the Bering Sea on Wednesday and was now heading in for repairs. An urgent call from the Far Eastern Fish Association in Vlad, relaying instructions from the parent ministry in Moscow for all ships to steam to the site and assist in the rescue effort, turned it about.

Ron Price switched on the landing lights under the P-3’s wing, lighting up his aircraft, and repeatedly flew low on a racetrack over the ship oriented northeast-southwest, pointing back toward the rafts, while trying unsuccessfully to talk to the radio operator below. The last passes were flown directly at the ship at six to eight hundred feet altitude, with the pilots flying and the flight engineer flashing Morse code on the lights.

“CEF” might have meant something to the Coast Guard, who suggested the procedure, but it is unclear if it was the blinking signal or the aircraft maneuvers that finally got through to Sinyavin. After the fifth or sixth pass, apparently now comprehending but still mute, Sinyavin headed directly toward the site.27 Once it was clear that the Russians were on track, Price pushed up the power levers and put his aircraft into a climb, heading east toward Shemya’s fuel trucks.

XF 675 has been on station at low altitude more than four hours. Price no longer has the minimum required fuel, twenty-three thousand pounds, to get back to Adak. As Crew 11 climbs out, CG 1500 tells them he can remain on station for five more hours.

CG 1500 came on station long after sunset, and now he is alone overhead the downed aircrew. No one aboard the C-130 has actually seen a raft in the water at any time. More than once during the hours to come Bill Porter was to wonder anxiously if they were orbiting in the right place.

Finding of Fact. At 2036, XF 675 departed the area for Shemya after passing information about Mys Sinyavin to Coast Guard 1500.

XF 675 landed at Shemya AFB an hour and twenty minutes later, the beneficiary of the strong, gusty westerly that had been blowing all day, for fuel. There were less than six thousand pounds of usable fuel aboard at touchdown, enough for perhaps ninety more minutes of flight and well below Aleutian requirements. The goal was a quick turnaround for Adak, to return the aircraft for its next SAR mission.

Refueled, Price taxied toward the runway, to hear the control tower calling him with the information that Shemya weather was now below ceiling and visibility minimums, and the airfield was closed. Without a special instrument card that would grant him flight clearance authority under just these conditions, Price was required to return and wait out the weather. He did not. Ignoring the tower’s strident repetitions of its bad news into his earphones, Price rolled PD-9 into takeoff position, confirmed with Conway they would exercise emergency authority to go anyway, and called for “max. power.” XF 675 was off Shemya for Adak at 11:51 P.M.

On the flight home, Conway’s crew was quiet, tired and depressed. Despite Scone 92’s good work, they were pissed off at the joint service headquarters in Yakota, which had harassed them on station, and by their sister service that had tried to delay their return to Adak. They knew only that at least nine men from the crew of AF 586 appeared alive at the outset, but perhaps fewer were alive now. Even with Sinyavin on the way, no one aboard PD-9 could be confident that this would end other than in tragedy.

Someone who had the bigger picture in mind must have quietly squashed the FAA flight violation that was immediately filed by Shemya’s tower supervisor against Ron Price, the pilot in command, as it moved up the line. Price never heard anything more about it.

Finding of Fact. By 2200, Coast Guard 1500 had communicated with Mys Sinyavin and had ascertained that her estimate to the scene was 2400. Her position was 52°34'N, 166°52'E.

Porter marked the position of the rafts with an electronic datum marker buoy and by flares. The expectation was that the marker buoy would drift on the surface along with the rafts, signaling their position to the C-130. Later, Porter headed over to the surface contact, a few minutes’ flight time away.

The sudden appearance of another American aircraft overhead might have confused the crew of Mys Sinyavin, then at top speed but making very slow progress heading east northeast, downwind and across high seas, roughly in the direction indicated by the U.S. Navy aircraft some time ago. The seas were hitting the ship on its stern quarter, lifting it high from behind with each crest in a wrenching, corkscrew roll that ended when the bow slapped down into the following trough, and the cycle began again with the stern heaving up and Sinyavin’s screw chewing air. The wind had freshened, too. Beneath the clouds, the sea was lit only by Sinyavin’s deck and bridge lights leaking weakly out across the water through the rain and snow, and by its powerful searchlights on the bridge, spearing the sky ahead crazily as the ship pitched and rolled.

Rick Holzshu finally managed to gain contact with Sinyavin’s radioman, a sailor named Makhov, on VHF FM channel 16.28 When a second voice replaced the first, Bill Porter was able to explain that others, not they, were in distress. “No, no,” Porter clarified, speaking slowly, “men in the water. Course 090 at 25 miles. Please go.” They exchanged names. “Maslov” was the name of the Russian on the radio. He was not a radioman, but he spoke English and Makhov did not.

“Bill,” the Russian replied, “Bill, we go. Who in water?”

Unaware of the communications that had already snapped back and forth between Washington and Moscow, Porter’s reaction was to be coy, cautious. He could not be certain if Sinyavin would risk its own crew to attempt a hazardous rescue of downed American servicemen. He did not know that the Defense Ministry had already informed nearby Soviet Navy, border guard, and fisheries vessels about the drama onstage more than three hundred miles east of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatski.

“Maslov, friends in the water. Please go.”

“I understand, Bill.”

Sinyavin was making good less than ten knots. Porter was flying back and forth, between the Soviet ship and the rafts. He renewed the flares in the water each mark overhead where he thought the rafts were, and laid a string of flares to guide the ship, route markers across an otherwise featureless sea. Arbuzov later confirmed that CG 1500 led him to the rafts, constantly correcting their course through the high seas.

“Maslov, you speak good English.”

“Thank you Bill. Bill, how far?”

“Course 090° at 12 miles.”

“Bill . . . you speak good English, too.” Porter’s crew erupted in laughter.

High overhead, Scone 92 heard the exchange. He relayed the news to XF 675 and Shemya Tower that the Russian fisherman was Mys Sinyavin, international call sign UONW. Alan Feldkamp felt the pressure come off. He knew that the ship had been slightly off course heading for the Americans. Now that was being corrected.

Finding of Fact. During this timeframe, the conditions of the survivors reflected the effects of exposure to the elements. Petty Officer Brooner, Airmen Rodriguez and Garcia, and Petty Officer Hemmer became lethargic and required a great deal of attention from the other survivors. They had to be kept continually propped up in the raft, talked to, and even slapped, to keep them awake.

Shepard thought that everyone had to stay awake to survive. Falling asleep, he believed, was the first step in the progression through unconsciousness to death. Bailing, signaling, singing, and talking were all part of the campaign against dozing off, and heading down that one-way path. Aboard the Mark-12, the afternoon had begun with John Ball telling stories about wild coeds and toga parties at Ohio State, his wife’s alma mater, and Matt Gibbons singing snippets of half-remembered rock lyrics. Now everyone was just trying to conserve heat and stay alive.

Dying of exposure is less an event than a process. Depending on conditions, that process can be quite swift, only minutes long in extreme cases. In other circumstances, on tropical seas and with an occasional supply of rainwater, it can take weeks, and finally come in the forms of fatal desiccation or, more slowly, death by starvation.29

In the early 1940s, three German doctors conducted a series of sadistic medical “experiments” on human subjects, victims selected from the population of Jews and Russian POWs in Nazi prison camps. The lead and most enthusiastic researcher was one Dr. Sigmund Rascher, variously identified as a Luftwaffe captain or SS hauptsturmfuehrer. The others, Doctor Finke and Professor Holzloehrer, assisted Rascher in his horrible experiments on freezing and rewarming living humans. Ostensibly, the data collected were to form the scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of hypothermia experienced by Luftwaffe aircrews bailing out into the North Sea, who often survived immersion for only an hour or two. At least three hundred prisoners were used in the experiments, one-third of whom died immediately.30

Rascher’s data on severe hypothermia (which he induced by submerging some prisoners in tanks of ice water and by exposing others naked to winter conditions at Dachau and Auschwitz) are unique. Data from volunteers, for obvious reasons, stop at approximately 35 degrees C (95 degrees F) core temperature, and animals and humans exhibit very different physiological responses to cold. Among other things, the Rascher data produced a curve, matching hypothermia symptoms to core temperature. He found that death was inevitable at a core temperature of 28 degrees C.

In their rafts, Crew 6’s survivors would first move swiftly through the familiar discomfort of being chilled to an intense, bone-deep cold marked by furious shivering, vibrating continuously and uncontrollably. This passage would signal a two degree drop in core temperature, to 35 degrees C. The shivering would be ineffective in masking great pain from the cold. Next, the loss of two or three more degrees would be marked by long periods of “cold narcosis” (torpor) punctuated by short interludes of bare consciousness, and an ominous end to the shivering, as if the body had gone beyond trying to stay warm. In fact, shivering stops because muscle glucose has been exhausted.

Below 30 degrees C, blood pressure would already be almost undetectable and pulse and respiration would slow as if in hibernation. Then consciousness would be lost, and death would follow as core temperature sank below 27 degrees.

Crew 6’s life vests, anti-exposure suits, and rafts postponed that quick progression to death, but now, huddled in their raft for about eight hours, the men in the Mark-7 raft were running out of time. And their raft was deflating.

The Mark-7 raft is nothing more than a scaled-up Mark-4, a four-man raft. It is a roughly rectangular tube with rounded corners above a rubberized sheet floor: no bow, no stern, no insulation from the cold water below. An inflatable thwart near one end holds the raft’s sides apart and can serve as a seat. Compartmentalization (two in the raft, one in the thwart) prevents a single puncture from sinking the float. The hull compartments inflate automatically, but the seat must be pumped up by hand. The nine had never pumped up the thwart. Then they discovered an air leak at one end. Wagner thought that an inflation valve inadvertently bumped during bailing caused the leak. The hand pump could not be made to seat on the valve, and air kept leaking out.

Jim Brooner had begun complaining to Ed Caylor about the cold almost immediately, as soon as he got into the raft, his short legs next to Bruce Forshay’s on the other side. He said he was wet up to his thighs. Brooner, five feet nine inches tall and 150 pounds, strong and wiry, was a tough young man. He had been a rodeo competitor in high school, but nothing in a dusty show ring had prepared him for this. During the night, Brooner slumping in his place, dropped down even lower in the cold water that nearly filled the raft, and had to be lifted to a sitting position repeatedly. Sometime before midnight, he could no longer be forced to talk and sing. He first started mumbling incoherently and then, later, fell silent.

Rodriguez, who had leapt bravely into the water with Caylor as part of the attempt to save Grigsby, must have been terribly cold from the outset, too. When his body and survival equipment were returned to the United States a week later, the suit exhibited a long gash down one of the legs. Because of it, he had been largely unprotected from the cold, and the water pooling inside the suit around the large femoral arteries and veins in his legs must have accelerated the cooling process.

Finding of Fact. At approximately 2300, Airman Rodriguez succumbed to the elements.

Airman Randall Paul Rodriguez, from Denver, Colorado, was the first survivor to die in the Mark-7 raft, but not by long. He would be joined in death within the next two or three hours by the other two young, enlisted sensor operators on the crew, PO James Dennis Brooner and Airman Richard Martin Garcia.

Randy Rodriguez joined the Navy right after graduating from Lincoln High School in Denver. He died a few days short of his second anniversary in the service. The months-long training program for air antisubmarine warfare technicians, and P-3 aircrew members meant that Rodriguez was very new in the squadron. He had checked into Patrol Squadron 9 just over three months earlier, on 20 July. At the time he died, Rodriguez, like Rich Garcia, was making $485 a month.

Within ten or fifteen minutes after the ditching, Airman Rodriguez’s core temperature—the temperature of his brain, spinal cord, heart, and lungs—had begun to drop. His valiant attempt to help drag the Mark-7 closer to the floundering Lieutenant Commander Grigsby would have accelerated Rodriguez’s loss of life-sustaining heat. That awkward effort, hanging on the crowded raft and kicking into the face of the wind or sea impeded by the lobes of his inflated life vest, must have been exhausting. Each slow and ineffectual kick would have pumped the thin layer of warmed water trapped between his body and the QD-1 out through the rip in the leg of the garment, and pushed warm “core” blood into his arms and legs, where it would cool more quickly than if he had remained in the raft. It would have been an effort to scramble back aboard, too.

At first, Master Chief Shepard, sitting on Rodriguez’s right hand in the Mark-7 and near its deflating end, thought that the young sensor operator “appeared to be in decent shape physically.” He thought that the others, Brooner and Garcia, looked OK then, too. But hours later, as darkness fell and into the night, Rodriguez began to fail rapidly.