Chapter One

Building a Cavalry Regiment

Canada was not ready for battle when the Second World War broke out in September 1939. The nation possessed a tiny regular army, navy, and air force. Its greatest strength lay in the regiments of Non-Permanent Active Militia, made up of part-time soldiers and a leavening of Great War veterans, found in every major centre from coast to coast. In the early days of the war, civilians flocked to their local armouries to fill militia regiment ranks. But numbers alone did not make them ready; it would take time to build the weapons and machines necessary to equip them fully. The reality of 1940s industry and technology and advances in the nature of modern warfare meant that years of training were needed to master the new machines, weapons, and communications equipment and the methods to employ them well enough to meet the German Army on the battlefield.

The Early Years, 1787-1866

A regiment, however, is more than people and equipment. In the Canadian Army system, it is an idea — with a sense of purpose, traditions, and regimental spirit, born in communities across Canada — that takes decades to form. In the counties of southern New Brunswick, one such idea took hold among Loyalist regiments that had been granted tracts of land along the banks of the Saint John and Kennebecasis rivers when the new colony was formed in 1784. One of the new landowners was Colonel John Saunders, who led three troops of Loyalist cavalry that made up the mounted mobile arm of the famous Queen’s Rangers during the American War of Independence. After the war Saunders returned to England to study law, but in 1790 rejoined his former Ranger comrades-in-arms after being appointed a judge of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick.

By the time Saunders returned to the colony, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Carleton had signed the Militia Act of 1787, authorizing the formation of a provincial militia based on the structure of the Loyalist units that had settled together in the southern counties. At first, the militia was only a paper force that, in theory could call upon all able-bodied men in time of crisis. Britain’s entry into the European war with Napoleon’s France, however, revealed the need to improve militia efficiency. Reductions of the British regular garrison meant New Brunswick increasingly had to rely on itself for local defence in the event of French or American raids. The Chesapeake-Leopard affair1 of 1807 reminded many of the ever-present risk of war with the new United States, allied to France. In response, a system evolved for the annual muster of infantry battalions in every county, drawing on the experience of former Loyalist officers. In 1808, Saunders himself was appointed colonel in the New Brunswick Militia, beginning a tradition of public and military service by the Saunders family that forged the spirit of New Brunswick’s cavalry. Troops of volunteer cavalry began to be formed to augment the county infantry battalions sometime during the Napoleonic period, but the establishment of volunteer mounted units was formalized only by the Provincial Militia Act of 1825. In the first half of the nineteenth century, troops of volunteer cavalry were raised across the river country of southern New Brunswick. The volunteer nature of their existence made them unique in an era of compulsory militia service for every fit male. The cavalry troops, along with a handful of volunteer artillery batteries and infantry companies, drew upon those with the most interest in military service, and often those willing to pay from their own pocket for the honour of serving. The state of training, equipment, and military readiness in those early troops depended entirely on the resources and will of the men who offered their service. Each was usually responsible for providing his own horse, saddle, uniform, and sword.

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 to 1848, the militia fell in and out of favour in the colonial legislature, its fortune tied to times of emergency, such as the Aroostook troubles of 1839.2 It remained alive largely through the spirit of the volunteers, perhaps most strongly displayed in the cavalry that, by 1848, numbered eleven widely dispersed troops. On April 4 of that year, the troops united under Militia Order Number 1 as the New Brunswick Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry, considered by the modern 8th Hussars as the date of their founding. Regimental headquarters was established in Fredericton to command troops from the counties of Charlotte, York, Kings, Carleton, Westmorland, Queens, Sunbury, and Saint John. The roll of officers was a veritable who’s who of old New Brunswick surnames: Hatfield, Jones, Northrup, Gillies, Lyon, Nutter, Drury, McMonagle, Upham.

At the same time, 1848 began a period of sharp militia decline and provincial budget cuts. The appointment of Sir Edmund Head as New Brunswick’s first civilian lieutenant-governor was mainly positive and signalled the arrival of elected responsible government in the province. But most elected representatives had little interest in military expenditures. They found the compulsory militia muster especially loathsome, and in 1851 passed the Suspending Act, putting an end to annual musters and training. For the next twenty years, New Brunswick’s militia ceased to exist except on paper. That the militia did not die was thanks to the tradition of service by volunteers who maintained the spirit and being of many New Brunswick units. In Sussex, in Kings County, a surviving troop of the Yeomanry Cavalry still gathered annually to drill all during the lean years until the official birth, according to today’s Department of National Defence, of the New Brunswick Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry in 1869.

Keeping the militia idea alive during the 1850s, however, was a struggle even though, by the middle of the decade, the Crimean War and reductions to British regular garrisons caused Britain’s North American colonies to become interested once again in defence and military service. In the Canadas, these developments led in 1855 to a new Militia Act that laid the foundations for a volunteer militia. New Brunswick’s legislature, however, was more reticent, sanctioning military drill only for volunteer units. Despite legislative indifference, the volunteer militia grew in popularity, forcing the province to acknowledge the new movement officially in 1859. The next year, the legislature even voted modest funds for training and equipping seventeen volunteer infantry and artillery companies and a troop of cavalry formed from the existing Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry.

Appointed to command the newly authorized cavalry troop was John Saunders’s grandson, also called John. He was the third John Saunders to serve the colony of New Brunswick in uniform and in public office. His father, John Simcoe Saunders, commanded a company of the famous 104th (New Brunswick) Regiment of Foot during the War of 1812 and went on to become President of New Brunswick’s Legislative Council at the time of confederation. It was the Saunders family’s tradition of public and military service that forged the spirit of New Brunswick’s cavalry. The grandson, born in 1830, was groomed in the family heritage and his destiny fulfilled by building a cavalry regiment in the province.

Born in London, the younger Saunders was raised in southern New Brunswick, then educated in England at Winchester and Oxford. At age twenty-nine, he returned to New Brunswick to build his life and a regiment of cavalry. He immediately enrolled as an officer in the new volunteer militia and was named captain of the cavalry troop, which paraded smartly in blue uniforms and sabres for the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860. After the royal visit, Captain Saunders bought a large land tract downstream from Sussex at Apohaqui, where he built a farm and estate that became known as Fox Hill. From there, he began to breathe new life into the volunteer cavalry troop in Kings County.

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 created real defence needs in New Brunswick and gave shape to Saunders’s vision. Saunders was called to Fredericton as the “cavalry representative” in a commission of officers established by Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon to study how to improve militia efficiency. The ongoing conflict to the south and the Trent Affair of November 18613 raised the spectre of war between Britain and the United States and inspired the temporary Militia Act of 1862. The act kept the old compulsory sedentary county units but placed the main emphasis on growing the volunteer “active” force. The number of volunteer cavalry troops soon rose to four, and a year later seven troops were spread across Kings and Westmorland counties. In 1866, several were despatched to the border with Maine to defend against the Fenian threat. In November of that year, five of the seven troops mustered at Hampton Station for a regimental inspection. Numbering 299 men and known as Saunders’ Horse, their commander was now a lieutenant-colonel.

From Confederation to South Africa, 1867-1899

By 1867, the idea of a provincial mounted regiment was a reality, and summer camps for the volunteers were becoming routine. The men who turned out to train with Saunders’s cavalry came from farms and small towns throughout Kings and Westmorland counties. The regimental historian, Douglas How, wrote glowingly in The 8th Hussars: A History of the Regiment, about the men who formed the unit: “They are essentially a country and small-town people, as solid as the rocks that rim their Fundy shores. From the men folk of this solid breed have come, for generations now, the 8th Hussars and their predecessors. No Regiment could want for better stock.” The old road connecting the Kennebecasis River valley to the Petitcodiac bound these communities together. By 1860, it also bore a railroad that could assemble the small-town troops into a regiment.

In a general order dated April 30, 1869, The New Brunswick Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry was recognized formally as a part of the Canadian volunteer force. Afterward, Saunders ensured there was always a summer training camp for the regiment. Some years it was a brigade camp in Fredericton; in other years they gathered at Saunders’s Fox Hill farm, which became a de facto regimental depot. In 1872, the regiment, drawing from the number of the militia district in which it served, was designated the 8th Regiment of Cavalry, a numerical designation that, like the Saunders family name, became part of its identity.

After Confederation, limited Canadian government funding for volunteer militia units allowed the purchase of modern rifles and carbines, saddlery, uniforms, and even a daily wage for the days men mustered at summer camp. Mounted troops still brought their own horses, but were compensated for doing so. Men sometimes still paid out of their own pocket to serve, however: during the lean 1870s, when government funds were cut for summer training camps, the 8th Regiment of Cavalry gathered at the expense of Saunders and his troopers. In the years when no summer camp funds were available, the regiment frequently gathered at Fox Hill. On a few occasions, the railway made it possible to assemble at Shediac, on the eastern border of the regimental area.

While at camp, the men trained in marksmanship, drill, formation riding skills, and basic cavalry tactics. Canadian militia senior staff who came to inspect the unit’s proficiency held the 8th Cavalry in high regard, even in tough times. How’s history refers to an 1876 official regimental report noting that “reduced funds for militia training were becoming severely felt” and that “it required considerable determination and courage for both officers and men to maintain their regimental organization under these conditions, yet all ranks had sufficient enthusiasm to keep up the work.”

The regiment’s dedication to maintaining high standards meant that, when Governor General the Marquis of Lorne and his wife visited New Brunswick in 1879, the 8th Cavalry, resplendent in blue uniforms, was given the honour of providing the mounted escort wherever the vice-regal couple travelled. The detail was commanded by Major James Domville, future Member of Parliament and the next commanding officer of the 8th. The Marquis’s wife, Princess Louise Caroline Alberta — who endeared herself to many Canadians through her kindness, charitable work, and ability to feel more comfortable among farm and working folk than among high society — made a great impression on the regiment and began a long association with it. In 1884, it became known officially as the 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Regiment of Cavalry.

The new name, however, could not provide funding for training, and resources remained scarce through the 1880s and into the 1890s. The responsibility for keeping the regiment in being through those lean years became James Domville’s. Summer training camps continued, but on a much reduced scale, with three troops of the regiment mustered one year and the other four troops the next years to maintain some level of interest and martial skill.

Since the days of Saunders’ Horse, the regiment had dressed in the pattern of European hussars: blue uniforms with black fur busbies, yellow braid, and spurs. Hussars, a term originating in Hungary, referred to small, highly independent units of light cavalry ideal for operating detached from the main army on reconnaissance, patrol, or as a rapid mobile force able to strike enemy weak spots or isolated posts. Before Princess Louise’s name was associated with it, the regiment had been known unofficially as the 8th Queen’s Canadian Hussars, and by 1889 the unit was classified on Ottawa’s militia list as hussars, as befitted its role in the defence of New Brunswick. In 1892, the various titles and ideas associated with this provincial force of cavalry came together in the form it would take to war: the 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars.

8th Hussars at summer training camp, circa 1895.

PANB P33/90

Under its new name, the regiment continued to receive positive reports from militia inspectors despatched from Ottawa. The camps where they gathered were held all over southern New Brunswick, in and out of the regimental area, including at Domville’s own residence at Rothesay. A number were held on the broad valley floor and rolling hills outside Sussex. As a railway junction town at the centre of Kings County, it was the perfect location and, beginning in 1892, muster camps at Sussex became an annual affair. After watching the regiment at work that year, Major-General Sir Ivor Herbert, the British officer appointed to command the Canadian Militia, remarked to Domville that, “you have the best cavalry regiment in Canada.”

In the two decades leading up to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Canadian international affairs and defence matters took on greater importance. Defence budgets grew larger, fostering an improved militia establishment. The 8th Hussars was re-organized into four squadrons each with two troops located at Sussex, Hampton, Springfield, and Sackville. The period saw great improvements in training and professional development opportunities for officers at major establishments run by the Permanent Force at Kingston and Quebec City. In 1899, a graduate from a number of those new courses was appointed as the next commanding officer of the 8th Hussars. Lieutenant-Colonel H. Montgomery Campbell was the great-grandson of Justice John Saunders. His uncle John Saunders willed him the family estate at Fox Hill, strengthening the regiment’s connection to that family and that place.

Campbell’s appointment seemed to announce that it was time for the 8th Hussars to fulfill its destiny — the later stages of the South African War proved the value of troops mounted on horseback for all the types of tasks traditionally associated with hussars. Events, however, proved otherwise. The regiment was not called out en masse during the war; rather, individual volunteers came forward to serve in all the contingents Canada sent to South Africa. Nine officers and fourteen other ranks went overseas, most returning to the 8th Hussars with their experience of modern war. During the South African War, the British Army’s ability to provide proper sanitation, medical care, balanced rations, and even clean water in the field were in their infancy. Like many other veterans of that conflict, one Hussar, Russell Hubly, returned home with tuberculosis. He suffered for a year before succumbing in 1901. Hubly had been principal of the superior school at Hampton when the war broke out. He volunteered for the first contingent and went to South Africa with the New Brunswick-raised “G” Company of 2nd Special Service Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment. Before becoming ill, Hubly survived the Battle of Paardeberg Drift. He was an avid writer, and sent detailed letters of his experiences to the Kings County Record. His writings from the period present one of the best accounts of soldiering during that historic first Canadian deployment abroad. In 1902, they were published in a well-known period pamphlet titled “G” Company or Every-day Life of the R.C.R. The former cavalryman from the Hampton troop was escorted to his final resting place in Sussex by an honour guard of forty Hussars. Hubly was the first member of the regiment to die as a result of active service.

As the threat of war in Europe grew stronger in the early twentieth century, the 8th Hussars entered a new era of preparation. Summer camps in those days before 1914 were among the best attended and funded in the regiment’s history. The training was supervised and inspired by Boer War veterans who understood that modern long-range rifles, artillery, and machine guns made cavalry charges with lances and sabres highly unlikely in the event of war with a well-equipped foe. However, the value of soldiers trained to handle modern rifles and mounted on horseback for rapid movement around the battlefield had been amply demonstrated in South Africa. With this in mind, the 8th Hussars introduced many young New Brunswickers to the basics of military life. One wrote fondly of his first summer as a Hussar trooper:

When the time came for the big sham battle what should I find but that I had been chosen as a runner for the regimental commander; a high distinction and one to be treated accordingly, especially by a rookie. Then came the time at the very peak of the battle when I was despatched with a message of some considerable urgency. But as luck would have it I chanced enroute upon a sight so tempting that I quite forgot my duty. It was a field thick with strawberries. I jumped off and fell to gorging myself. So good were they that I was oblivious to the approach of the enemy until I was rudely taken prisoner.

The youthful soldier apparently learned a lesson in vigilance and duty that day. Trooper Milton Fowler Gregg of Mountain Dale (now Snider Mountain) went on to become one of New Brunswick’s most decorated soldiers, an inspiring trainer, university administrator, politician, and diplomat.

That Milton Gregg did not go to war in 1914 as a Hussar was telling. For a variety of reasons, Sir Sam Hughes, Canada’s minister of militia, chose not to mobilize militia units but to create ad hoc battalions in each province. Hughes called for volunteers from a number of New Brunswick’s existing militia units. Those from the 8th Hussars wanted to go overseas together. The regimental historian captured the mood: “After decades of preparation for exactly this, there could be no other thought.” But it was not to be. Once they understood the regiment would not be called out, each of the twenty-nine officers volunteered as individuals for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (C.E.F.). Hundreds of non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and troopers did the same.

The largest single contingent joined the 6th Canadian Mounted Rifles (C.M.R.) in 1915, forming most of a squadron. The battalions of the C.M.R. were composite units formed from militia cavalry units across the country. The 6th was the Maritime provinces’ contribution and was recruited mainly at Amherst, Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1915, the unit reached the southeast portion of the Ypres Salient, where it went into the lines as infantry and took part in the struggle to hold the front at Mount Sorrel. But by year’s end, the Canadian Corps overseas was reorganized, and, in January 1916, the 6th C.M.R. was broken up to provide replacements for the 4th and 5th Battalions of the Canadian Mounted Rifles. They would be needed in the years of war and bloodshed that lay ahead.

Hundreds of other former Hussars served throughout every division in the Canadian Corps. Indeed, the regiment provided the nation with a wealth of trained individuals. But this scattering of personnel created a problem after the war was over: how to perpetuate battle and campaign honours — the hard substance of regimental spirit — won by locally raised battalions of the C.E.F. For most regiments, the problem was solved by permitting any militia unit that contributed over two hundred men to an overseas battalion or could prove that at least two hundred and fifty of its members had served in that unit at the time of a key action to incorporate the honours of the Great War battalion into its own. The 8th Hussars, however, hoping to go into action together, hung on too long as a unit. With the exception of the squadron mobilized with the 6th C.M.R., most Hussars volunteered in small packets, preventing the proud 8th Hussars from laying claim to the honours of any overseas unit. The regiment’s veterans continued to press for the recognition of their wartime service as a unit, however. Finally, during the Second World War, the 8th Hussars won the right to add to the regimental colours — known in a cavalry unit as the guidon — the honours of the 6th Canadian Mounted Rifles, including the bloody clash on the Somme in 1916, where so many of them had fought as replacements for 5th C.M.R.

After the Great War ended, the militia generally found itself chronically underfunded and kept alive by a tiny handful of dedicated individuals. The 8th Hussars and some other older regiments, however, were exceptions to this gloomy scene. While the 8th missed out on the Great War as a formed unit, the officers and men who returned to the Hussar guidon in the years after the war brought with them a wealth of combat, organizational, and training experience — the first postwar commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Markham, had commanded the Hussar squadron in the 6th C.M.R. The Hussars, like other old militia regiments, provided a place for those interested in maintaining a level of defence readiness for Canada, including many “returned men,” the veterans of the Canadian Corps — as well as young troopers eager for their chance to serve. Seasoned veterans passed on to a new generation the lessons learned in the Great War and their knowledge of the wider world beyond New Brunswick. The regimental history records one new trooper’s impression of his veteran officers and NCOs upon meeting them at summer training camp: “They seemed quite a bit older and more worldly than we did. They had their campaign ribbons up. They made us newcomers feel pretty green and out of place, but not intentionally. They kidded us about not being ‘real soldiers’ but after awhile they made us feel at home.”

All militia units faced the challenge of reduced budgets, fewer days allotted for summer training, and a corresponding drop in the number of soldiers allowed to participate in training — most camps in the 1920s saw fewer than a hundred men and horses, a far cry from camps in the previous century. But unlike most other units, the 8th Hussars also grappled with a problem that went straight to the core of its identity: was there still a place in the modern army for horsed cavalry? The power of a highly mobile regiment of mounted soldiers had kept the Hussars spirit alive for almost a century, but the technological innovations introduced during the war now meant that ideas about what kind of transportation mounted units should use were changing fundamentally. At first, the Hussars continued to attend summer training at Camp Sussex with horses, but changes got under way: in the 1920s, a signals section was formed as part of the squadron in Sussex, and in 1932 the squadron in Hampton created a machine-gun troop.

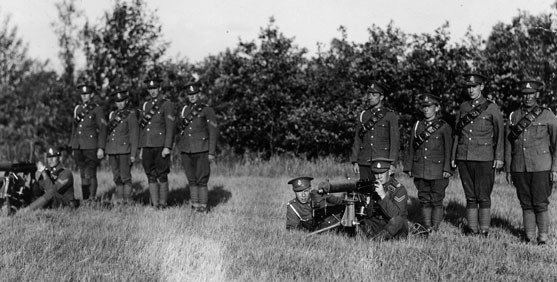

Machine-Gun Troop of Headquarters Squadron training between the wars.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

But just as the training for modern militiamen began to grow more complex, the Great Depression compelled even deeper funding cuts, and in 1931 the regiment once again called upon its members to train at their own expense. Yet new technologies and weapons made it impossible to create a soldier during an eight-day summer camp. The solution, part of a movement that swept across the militia in the 1930s, was to gather by squadrons at town halls, church halls, or even barns, to train on evenings throughout the winter — thus the militia “drill night” was born. Anyone who wanted to make his own way to train for free could do so, although pie socials and other fundraisers raised some money for transportation costs and hall rentals. As the 1930s wore on, an increasing number of Hussars came forward to train. Some no doubt were prompted by a growing awareness among Canadians that trouble was looming once again around the world. Though we often assume the nation was oblivious to the rise of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, many young Canadians followed events in the newspapers closely, and expressed their concern by walking miles to attend drill night. New Brunswickers, however, had a particular incentive to volunteer their time and energy thanks to the leadership of two extraordinary commanding officers of the Hussars, both of them veterans able to inspire men to serve.

Lieutenant-Colonel A.T. Ganong, Milton Gregg’s neighbour on Snider Mountain and a troop leader in the wartime 6th C.M.R., commanded the Hussars from 1932 to 1936. Under Ganong’s leadership, Hussars paid their own way to camp and evening training raised numbers back to more than one hundred. His 1933 regimental report, however, reveals both promise and frustration: “In reviewing the work of the past year I am satisfied we have made progress in all respects, both training and organization, we are in good shape, but do hope that the time will soon come when the Government can recognize the value of the militia by granting more funds for its training.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Keltie Kennedy at his Headquarters tent, summer training camp, late 1930s.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

8th Hussars parade under Lieutenant-Colonel Keltie Kennedy at Saint John, New Brunswick, for the coronation of King George VI in 1936.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

One of the men on whom Ganong drew heavily to build the drill night training system was Major Keltie Kennedy, who would succeed Ganong as the regiment’s commanding officer. Although badly wounded serving in the artillery during the Great War, Kennedy was an unstoppable force. In the early 1930s, he was appointed to command the squadron in Hampton, and it was under his leadership that the machine-gun troop was formed. His artillery service made him aware of the complexity of modern military training. He told his troop leaders and NCOs to inspire their troopers: “Work with them, talk to them, sell them on the regiment, and they’ll be Hussars all their lives.” New members of the regiment, such as Robert Ross, P.M. “Frenchy” Blanchet, Len Ewing, Howard Keirstead, and Clifford McEwen, responded eagerly to the leadership of Ganong and Kennedy and made ready to take the Hussars to war.

During the winter of 1935-36, the Canadian Army underwent a major reorganization as the Department of National Defence reacted to the growing threat of Hitler’s Germany. On May 11, 1936, orders arrived in Sussex that the 8th Hussars was to become “motorized cavalry,” and outlined provisions for the 1936 summer training at Camp Sussex: “This year cavalry units will be trained mechanized. In view of the above, no horses will be brought into camp, but privately owned motor vehicles will be brought in at the rate of one for every eight personnel; this will allow eight vehicles per cavalry regiment.” It was a modest beginning, but a major step was being taken toward readying the 8th Hussars for the looming world war.

That fall Kennedy was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and took command of the regiment. He was the right man to have at the helm for what happened next. It is said that, when he assumed command, “he could feel another German war coming in the very bones of the leg the Germans had maimed 20 years before. That premonition drove him through work days as long as 18 and 20 hours from the day he took over until the day his fears were realized.” Kennedy understood that the next war against Germany required mastering the internal combustion engine, off-road driving, and the radio and machine gun. Weeknight training had new purpose.

Others in the upper echelons of Canadian Army leadership understood, too, and in 1938 they designated the 8th New Brunswick Hussars as a divisional mechanized cavalry regiment. In many ways, this was the same role for which the regiment had trained and prepared for decades. Kennedy told them, “Remember our role and our tasks are the same as they were in the days of Genghis Khan. Our mounts and weapons have changed and our job at present is to learn how best to use them.” Kennedy trained the 8th Hussars for reconnaissance patrolling, flank screening, raiding, quick attacks to seize key terrain, rapid mobile response, pursuit, and covering withdrawals. In the past, the unit had trained to perform these traditional cavalry tasks on horseback. Now the troopers learned to do them far more rapidly in civilian automobiles, rented from their owners for ten dollars a day. The improvised nature of their training, bouncing over the hills of Sussex Vale in civilian cars, seemed farcical to many who longed for actual modern armoured vehicles. Yet the German Army’s improvised armoured training with civilian cars in the same period was lauded as innovative.

In 1937, Lieutenant-Colonel Kennedy authorized only those men already trained in basic soldiering and mechanized cavalry skills to attend summer camp. He was on a mission. That summer at Camp Sussex, 191 officers and men mounted in thirty-five cars took to the field to exercise their new modern cavalry role. They trained with machine guns, land mines, and road blocks. They practised camouflaging vehicles, gas and anti-aircraft drills, and tactical movement by car in the field. The 8th Hussars learned that mobility had changed the nature of the war they might have to fight. Lieutenant E.W. George, sent on course in 1938 at the Canadian Armoured Fighting Vehicle School in Camp Borden, was struck by the prospect of modern mechanized warfare: “With a speed of 20 to 50 m.p.h., we will have to learn to have more respect for an enemy which has been reported seen about 100 miles east two hours ago.”

It was impossible for a part-time militia regiment made up of men with regular jobs, farms, and families to be trained fully for war, especially when no one really knew what that looming war would look like. What is extraordinary about Keltie Kennedy and the 8th Hussars is that they tried to do exactly that in those last years of uneasy peace, as Adolf Hitler’s Germany swallowed up Austria and Czechoslovakia. Kennedy appealed to his officers for their loyalty to go far above and beyond the duties of an underpaid volunteer militiaman. In 1939 he wrote an astonishingly revealing letter to them.

Commanding the 8th Hussars at the present time is not the easiest job in the world. Mine is the arduous task of endeavouring to keep the organization constant with the changes that are being made from time to time, of having a unit ready for mobilization at a moment’s notice, of keeping myself abreast of all new developments in our arm as well as the service generally, of learning new weapons and defences against them and condensing that information and handing it on to you to pass on to your commands, of trying to sell you new ideas and new policies required by the times and for which the country has found itself totally unprepared, asking you to sacrifice time, money, effort and to sell these same ideas to those under you until such time as the people and parliament can adjust to the new demands.

History records that the Western democracies, especially sleepy Canada, were unprepared for war in 1939. But Keltie Kennedy’s 8th New Brunswick Hussars were as ready as any underfunded militia unit could possibly be for what was to come. In the first minutes of August 26, the order to prepare for war arrived.

Lieutenant-Colonel Harold Gamblin guides King George VI on an inspection tour of the Hussar barracks, 1942.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum