Chapter Three

Italy: “The Big Con”

The convoy steamed north through the Irish Sea, then westward into the cold blackness of the North Atlantic in November. The first day dawned grey and foreboding even before the wind came up, but then the wind howled, the seas rose, and men’s stomachs turned — the great majority could not hold onto the rather fine breakfast served that morning. In one of those ironic moments of war, during that first afternoon on the cold wintery sea, the Hussars were ordered to take anti-malaria pills and were issued mosquito repellent. Those not praying for gastro-intestinal relief cranked on the rumour mill: wherever they were going, it was going to be warm and sunny. It was now clear to them that the Northern Ireland plan was a cover story.

Days later, the skies cleared and the temperature rose. The convoy clearly was headed south, but the destination was still secret. On November 24, they sailed into an incredible new Mediterranean world, first passing Tangier and then Gibraltar. Two days later, they came into port at Algiers with a great sigh of relief for not having encountered German planes or U-boats. The unit advance party had not been so fortunate. Under command of Captain Cliff McEwen, the small detachment of five officers and fifty other ranks had travelled a few weeks ahead of the main body to sort out administrative arrangements to receive the main body at its final destination. At that time, the Allies still could not claim mastery in the air and at sea in the Mediterranean, and as McEwen’s detachment sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar aboard the liner Monterey, twelve German bombers and torpedo planes found and struck the convoy. A radio-guided glide bomb hit the deck of the Santa Elena, carrying staff and equipment for No. 14 Canadian General Hospital, while a torpedo punctured her at the waterline. German bombs and torpedoes also hit a Dutch transport and a US Navy destroyer in the same convoy. Passengers and crew from the stricken vessels abandoned ship and took to life rafts. Captain “Kit” Graham was sitting down to supper when he heard the explosions. He remembers the Monterey listing hard over as she took evasive action. The fifty-five Hussars and three thousand other passengers aboard the Monterey rushed to their action stations, some being ordered to the rails in black-out darkness to assist survivors climbing up scramble nets. First up the nets were Canadian nursing sisters, many making the fifty-foot climb after having rowed their own lifeboats. Shortly after that came Dr. Bert Oja, one of the dentists in No. 14 Hospital, who had once served the 8th Hussars in England. Oja had dislocated his shoulder when he jumped off the Santa Elena, but after making the painful climb up the scramble nets, his first request, according to Graham, was “Get me a cigar.”

Captain Jack Boyer, H.Q. Squadron Sergeant-Major R. McAleese, and Regimental Sergeant-Major Cliff Northrup at Regimental Headquarters, Matera, December 1943.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

At Algiers, Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson and the Headquarters Squadron quickly had to leave the main body aboard the Samaria and go on ahead to join Cliff McEwen’s advance party at the final destination, where they were to accept delivery of new vehicles and set up camp. The fighting squadrons were to wait in Algiers until everything was in place. Robinson detailed the technical adjutant, Captain Homer Keith, and a work detail to retrieve Headquarters Squadron baggage from the hold of the Samaria but was denied permission by the colonel in charge of all soldier-passengers aboard: all passengers and kit were to stay aboard until full disembarkation was ordered, possibly not for days. When Captain Keith reported back to his own commanding officer about the state of affairs, Hunter Dunn remembers that, “George Robinson told Homer that the baggage was to be on the dock in two hours or Homer would no longer be a captain.” Keith marched into the ship’s hold with a troop of Hussars armed with rifles and fixed bayonets. No miscommunication or administrative red tape would stop the regiment from its date with destiny. Soldiers tasked with baggage guard were lined against the bulkhead at bayonet point while the necessary kit was off loaded. Robinson and his headquarters group made their connection on time and set sail again, first for Philippeville, near the Tunisian border, then aboard yet another steamer headed northeast into the central Mediterranean.

On November 30, the small convoy sailed past the western coast of Sicily and their destination became clear. They awoke on December 1 to see the Isle of Capri and the Amalfi coast slipping by, Italian tourist destinations made famous by poets Byron and Keats. They journeyed into the Bay of Naples under the looming Mount Vesuvius. Their steamship entered the great, bomb-blasted port of Naples, where their eyes drank in the sight of their first war-ravaged Italian town. They had finally arrived, but for what?

On December 2, 1943, Robinson and the Headquarters Squadron unloaded in Naples, met up with Cliff McEwen’s advance party, and prepared to take part in the largest deception and diversion mission of the war. The Italian campaign is sometimes treated as a “sideshow” that competed with the invasion of France for resources and as an alternate path of advance into Hitler’s Germany. In reality, the invasion of Italy was never intended to win the war by piercing the so-called soft underbelly of Europe and driving to the Reich. Instead, Allied policy for Sicily and Italy was to set the conditions for successful Normandy landings in 1944. Allied operations in Italy formed part of a calculated diversion, containment, and attrition mission aimed at convincing the German high command to despatch large forces to southern Europe, far away from the decisive Normandy and northwest European areas. This policy ensured that Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion, had the strength required to succeed, but it condemned Allied soldiers in Italy to difficult and seemingly hopeless fighting with the barest minimum of men, weapons, and supplies to keep a German force of almost equal size pinned down. The enduring problem of the Allied war in Italy was that the soldiers could not be let in on the secret that they were part of a great bluff, though a great many figured it out. “B” Squadron’s second-in-command, Captain “Tim” Ellis, figured that, if the generals really wanted to chase the Germans out of Italy and drive to Vienna, they could send enough men, ships, and planes to do it. During his time in Italy, however, he realized that was not the plan, and that their lot in life was to keep a large portion of the German military machine in Italy. He came to call it “The Big Con.”

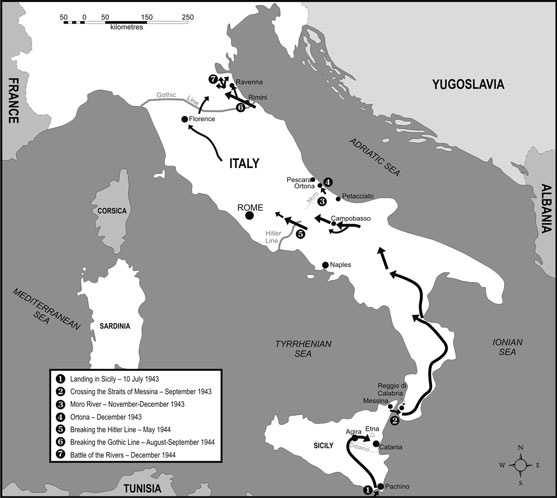

The Italian front, 1943-1944.

Mike Bechthold

In Naples, Lieutenant-Colonel George Robinson, the advance party, and the Headquarters Squadron met their outgoing counterparts from the 4th County of London Yeomanry, the British regiment from 7th Armoured Division whose equipment they were inheriting. Most of it was already worn and many of the vehicles not even functional. The trucks were two-wheel drive instead of the rugged 4x4 Canadian Military Pattern trucks the Hussars had left behind in England. Spare parts and tools were also in short supply, having already been pilfered by other British units staying on in Italy. Fitters from attached No. 70 Light Aid Detachment and driver-mechanics of “A” echelon (the fighting supply vehicles) and “B” echelon (the administrative and quartermaster vehicles) went to work getting enough vehicles running to allow them all to reach their assigned positions with 5th Canadian Armoured Division around Matera, on the other side of Italy. Matera is hidden in the foothills a short drive inland from Bari, the main supply base for Eighth British Army, to which the newly arrived Canadian division belonged. Getting there turned into a three-day job. On December 7, however, they set off, miraculously making the drive across the Italian boot in a single day, albeit not without breakdowns.

The Hussars seemed quite happy to get away from the slums around Naples. The new area around Matera lay on gently rolling foothills at the edge of the coastal plain astride the Adriatic Sea. “The country was more level in this area and seemed more prosperous. The towns and inhabitants were much cleaner looking than they had been in the Naples area and in the mountains.” The advance party set to work establishing regimental headquarters (R.H.Q.) in town and a training camp and ranges just outside. All three of 5 Armoured Brigade’s regiments shared the area, along with the Governor General’s Horse Guards divisional reconnaissance regiment. The surrounding countryside was ideal tank-training country. It drained well and was fairly rocky, avoiding the problem of Italian winters that limited tank movement: mud. Now all Robinson needed were tanks and crews.

The rest of the regiment, waiting at a transit camp outside Algiers for word of their destination, finally began the journey to Naples in mid-December, but not before a few Hussars had sampled the fleshpots of the casbah. After a few days camped in Naples, they made their way by sea around Italy’s boot to Eighth Army’s main supply base at the port of Bari, arriving two days before Christmas. Unfortunately, it took another three frustrating weeks before their tanks arrived, leading to inevitable griping. But there were reasons for the delay. To begin with, while the Canadian Army had agreed to take over decrepit British trucks, it did not want their battle-worn tanks. Back in October, General “Andy” McNaughton, 1st Canadian Army commander, had agreed to wait until Allied shipping and Italian port capacity allowed brand-new Detroit-built M4A4 Sherman tanks to be brought in from the great British base at Alexandria, Egypt. Everyone hoped these would be delivered as soon as the Hussar advance party arrived at Matera. But in December, the Allies crashed into freshly reinforced German positions along the Gustav Line and its outerworks, and shipping priorities focused on getting supplies to the Canadian, Indian, and New Zealand units in the close fight at Ortona. German medium bombers made that task more difficult by striking Italian ports and Allied supply convoys along Italy’s coastal waters. During an infamous raid on Bari on December 2, 1943, Luftwaffe bombers struck an ammunition ship, causing a massive explosion that destroyed port facilities, obliterated every ship in the harbour, and devastated the city itself. One of the ships smashed in the harbour carried a deadly cargo of mustard gas. Civilian and military casualties in Bari numbered in the thousands, and the port’s capacity was decimated. When the 8th Hussar fighting squadron personnel landed at Bari on December 23, it was still a ruin and functioning at only a fraction of its capacity. The 8th Hussars and the rest of 5 Canadian Armoured Brigade would just have to wait to get new tanks. There were few opportunities to employ tanks in the sodden, unfrozen earth of southern Italy in winter in any case.

In December, the advance party continued to ready the camp at Matera for the main body and embarked upon a great scrounge for turkeys so the unit might have a proper Christmas dinner. Meanwhile, Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson went up to the front line to see for himself how 1 Canadian Armoured Brigade tanks worked with Canadian infantry near Ortona. He took with him a command team made up of his Reconnaissance Troop leader, Herb Snell, and his intelligence officer, Lieutenant H.D. “Fearless” Fearman. They arrived on December 20, just as the battle for the small port city of Ortona itself commenced. It was an important sequence of events to witness and one that left a lasting impression on the Hussar observers. They were attached to Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Booth’s Three Rivers Regiment, then in the process of shooting Brigadier Bertram Hoffmeister’s 2 Canadian Infantry Brigade to the very edge of town. The Three Rivers Regiment had a reputation for aggressively sticking its neck out to assist the infantry units to which it was assigned. In the next few days, the Hussar team accompanied Three Rivers squadrons as they blasted machine guns out of the upper storeys of row houses and took apart buildings fortified as strongpoints by German paratroopers. They watched as tanks inched up the streets of Ortona, working closely with the Loyal Edmonton Regiment. Little did Robinson know that he would be in the same kind of battle before long.

8th Hussar “Town Guard” detachment forms up in Matera, in front of H.Q. Squadron wreckers and supply trucks and one of the regiment’s first brand-new M4 Shermans.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

In total, they were in Ortona for five days, watching the toughest parts of the town fight. They spent their last day, Christmas Eve, with a troop of Three Rivers Shermans despatched to a high bluff on the Adriatic coast two thousand yards southeast of town, where the Ortona Canadian War Cemetery now stands. At that point, the coast arches out into the sea to Punta di Acquabella. It was the perfect vantage point to observe buildings in the northeast corner of Ortona from which the Loyal Edmonton Regiment reported taking machine-gun and sniper fire. The lay of the land prevented the tanks inside town from getting far enough forward to get clean shots at these particular buildings. That day, George Robinson learned about the power and effectiveness of high-explosive shells fired from the Shermans’ 75mm guns. Directing the fire of the four Shermans in the troop, he reported how easy it was to bring accurate fire onto the targets even at ranges close to four thousand yards. When the shoot wrapped up successfully, Robinson and his team hopped in a truck and made their way back to Matera.

Another party of Hussar observers led by Captain Bruce that had been despatched to Italy months earlier to observe the evolution of Allied armoured methods in Italy also made it back to the unit at Matera. By then, the fighting squadrons had also arrived, so that, on Christmas Eve 1943, the whole regiment was reassembled. They gathered together for a grand feast but ate in great earnest. It was a grim Christmas that year in the Italian campaign, and the Hussars knew their turn was coming. During January they finally began to receive their new Sherman tanks and continued to adapt to the constantly evolving role and structure of Canada’s armoured regiments. The new M4A4 Shermans trickled in slowly, but there were enough to get crews started on learning the particulars of the tanks’ performance and maintenance needs. By January 19, they had forty-eight Shermans, six short of their total allotment. Most important, they learned the potential and limitations of their new 75mm guns. The Hussars had had some exposure to the few Shermans attached to each squadron back in England, but this was the first time each crew had got its own Sherman. The recce troop had to wait some months yet for its M5 Stuart Reconnaissance tanks, and made do in the meantime with armoured cars. Open-topped, four-wheel-drive White Scout Cars were also on order for key specialist officers — such as the medical, signals, and intelligence officers, and the technical adjutant — to enable them to keep up with the tank squadrons during mobile battles.

The regiment should have carried out conversion training to Shermans in January with its own 5th Division infantry units, but the demands of war had called 11 Canadian Infantry Brigade to the front early. However, the Hussars did have the opportunity to practise with the divisional artillery. The 8th Field Regiment, equipped with American-built M7 Priest self-propelled 105mm howitzers, was also camped near Matera. The job of the tank main guns was to take on targets that gunners could see directly with the comparatively small number of shells they carried inside the turret. The artillery, though, stayed further to the rear, fired much larger and longer-ranged guns, and travelled with far more ammunition — it could smother enemy areas located far out to the front with large doses of high-explosive shells. This was exactly the kind of friendly support the Hussars would need to take on hidden German tanks and anti-tank guns that were too far away for tank crews to see or hit. The field artillery was also an ideal tool for smashing Germans who came out of cover into the open to counterattack. The Hussars needed to know how to work closely with the artillerymen, so in mid-January all Hussar officers went to the ranges with the 8th Field Regiment. Each Hussar officer visited an artillery forward observation post located within sight of the target area and equipped with a powerful No. 22 radio set. There they observed, corrected, and adjusted fire for a troop of four or a battery of eight Priest 105mm guns. George Robinson had the honour of adjusting and firing a “Mike” target, which was reserved for targets important enough to bring down upon it the fire of all twenty-four guns in the field artillery regiment. The results were a powerful and comforting sight.

Captain “Ab” Shepherd, Regimental Adjutant, atop his new H.Q. Squadron Sherman in Italy.

LAC PA-213559

The whole regiment learned from units in the line what it was like to meet the enemy. They saw demonstrations of the latest captured German weapons, including the infamous and deadly 88mm dual-purpose anti-aircraft/anti-tank gun that could pick off a Sherman from two thousand yards away. They also saw their first German mortars and a Panzer IV medium tank roughly equivalent to their own. They heard about the latest trends in German mine and explosive trap warfare. The Germans were masters of improvising explosive devices to use not just as part of their defences but also to booby trap roads, culverts, potential parking areas, houses, and buildings — anything that might be useful to the advancing Allies. The Hussars learned that no place was safe and that every man must be on his guard against suspicious disturbances in the earth, holes in roads, and even attractive-looking souvenirs. Loads of sandbags arrived to line the floors of wheeled transport vehicles in the “A” and “B” echelons for blast protection from mines and explosive traps. In short, the 8th Hussars had as clear a picture of what awaited them at the front as any Canadian regiment ever had on the eve of its first taste of action.

On January 27, the wait came to an end: orders arrived to prepare to move. Hussars dropped tents, packed vehicles, and loaded tanks onto tank transporters. These last were essential: tank tracks, suspensions, and engines all had finite life spans, and long road moves wore out all ahead of their time. Much like today’s truck tractors and heavy floats used to ferry construction machinery from job site to job site, tank transporters carried the tanks from the training area to the battlefront. The 8th Hussars set off on the great journey north to Ortona. Major Bob Ross took off first with an advance party. “A” Squadron headed out next, led by Major “Frenchy” Blanchet and Captain Kit Graham as his second-in-command. Major Howard Keirstead took “B” Squadron, with Captain “Tim” Ellis as his second-in-command. Major Temple Lane and Captain Cliff McEwen rolled with “C” Squadron. George Robinson’s R.H.Q. tanks and the recovery vehicles of No. 70 Light Aid Detachment came next. Last but not least came the wheeled vehicles of the Headquarters Squadron, led by Major J.B. Angevine and Captain J.B. “Jack” Boyer.

The journey took them through the great Foggia Plain, where they saw a massive air base under construction that was to become home to a grand fleet of US Army Air Force bombers that would expand the bomber war into eastern Germany. Among the gathering air armada was a Royal Canadian Air Force squadron. The Hussars met up with the Canadian fliers at Campomarino, just north of the main Foggia base complex, at a halt just long enough for an impromptu baseball game. The next day they drove on to Vasto, where the Shermans were moved off the transporters and onto railway flatcars for the long haul north. In all, it took eleven days to move all the men and machines of the regiment to the front through the bleak, muddy, damp, cold winter of Italy. They all arrived in the war on February 9. Their new home lay near the farm village of San Leonardo, at the northern lip of the Moro River valley, four kilometres south of Ortona, which, two months before, had been all but obliterated during the Battle for the Moro. Now off the flatcars and moving under their own tracked power, the Hussar tanks drove into San Leonardo pelted by rain and wet snow. Their tracks so churned the already muddy track into their regimental area that the main work for the next few days lay in repairing the road. There would be no grand charges or mobile war here, at least not until spring. So much for “Sunny Italy.”

In 1944, the Ortona sector had turned into a stalemated front where combat was waged in the fashion of the Great War’s Western Front: raids into no-man’s-land and a steady exchange of harassing shellfire. After sundown on February 13, just days after the Hussars’ arrival, a wave of German shells crashed down among their Shermans. Luckily no one was hurt. The Hussars had dug slit trenches around their tanks, but after that first bombardment they spent the next several days digging deep, elaborate bunkers and protection for the tanks. A few days later, when a fairly dense concentration of twenty heavy German shells crashed into the regimental area, no injury came to either Hussar or tank. The same could not be said of tarps and pup tents above ground, many of which had light shining through shrapnel holes the next morning.

Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson took advantage of the Hussars co-location with experienced 1st Division infantry to set up an exercise and experimentation area in relative safety a few miles behind the front. Hussar crews left their tanks in the mud back north of San Leonardo and walked the exercise area behind advancing infantry, representing their “notional” armoured vehicles. They experimented with the best distances to travel behind infantry so that the tanks would be close enough to allow the two arms to operate as one. These were the skills both had to master for the coming spring.

During that winter pause on the Ortona front, a grand Allied plan for the warm dry campaigning season took shape. Since September 1943, the Germans had taken the strategic bait and sent large forces from all over Europe to hold the Allies at bay in Italy. The invasion of Normandy was scheduled for late May 1944. The broad mission assigned to Allied forces in Italy was to pull even more Germans there and away from western Europe by destroying those already manning the Gustav Line defences. It was a tall order, especially since the Allies possessed no great superiority in artillery or infantry. The plan called for aggressive use of tanks on a scale not previously believed possible in Italy’s hills by either side. But armour was the only domain where the Allies held superiority on the ground. Allied tanks would have to make up for the shortage in assault infantry.

The plan also called for a major deception to convince the Germans that the Allies’ spring offensive would include another amphibious landing, so as to disperse German reserves all around Italy’s beaches to guard against an invasion that would never come. Part of the ruse required the Canadians to “disappear” from the front in preparation for this amphibious assault. Meanwhile, the vast bulk of Allied land power in Italy, especially the armoured divisions, was to concentrate secretly in the Anzio-Cassino area, where the main German forces were located. If the ruse worked, the Allies might have a temporary margin of superiority there. With luck, it would last long enough to destroy these enemy units, forcing the German high command to despatch more.

The plan materialized in late February 1944. Orders arrived at the 8th Hussars command post to dig the tanks out of the mud, pack them up, and vanish to the south sometime early in March. But before the 8th Hussars left, they assembled to deliver the enemy a parting gift. On February 25, Howard Keirstead’s “B” Squadron was assigned to drive a few kilometres southeast to the Adriatic coast near San Vito, in Chietino. There, they were to join Major Ballie, their forward observation officer from the 8th Field Regiment. “B” Squadron’s task was to test out the prospects of using their 75mm guns in a predicted, indirect-type artillery shoot. In other words, the tanks would fire at maximum range at targets they could not see based first on map coordinates and then on corrections from a forward observer position. They would be joined by 25-pounder field guns and infantry 3-inch mortars for an experiment in predicted shooting on pinpoint targets. It was an exercise in coordinating the wide range of firepower available to the 5th Armoured Division. Ballie spent the day with Keirstead and Captain “Tim” Ellis, instructing them how to make the process work with tanks. Lieutenant Hunter Dunn was on hand from R.H.Q. Troop, too. Ballie, Keirstead, and Hunter Dunn worked with the Canadian artillery survey regiment to site the squadron firing position, complete with an aiming stake planted in front. “Tim” Ellis prepared to act as the observer to adjust fire. The target was a floating buoy anchored offshore. 5th Division’s artillery staff, led by Brigadier Herb “Sparky” Sparling, plotted out firing solutions to deliver shells from gun and tank locations to the target.

“C” Squadron H.Q. Troop crew commander linking into the regimental radio net before the Tollo Crossroads shoot, west of Ortona.

LAC PA-213561

On February 28, the day of the exercise, “Tim” Ellis moved up to the clifftop town of San Vito to observe the target from an armoured scout car equipped with a No. 19 radio set. Keirstead and Dunn directed “B” Squadron tanks into position behind the aiming stake. The field guns were first to fire at the target buoy, coming close. Next came the much shorter ranged 3-inch mortars, which also came close. Hunter Dunn remembers Brigadier Sparling jokingly remarking, “the tanks are next, let’s get the hell out of here!” Crews took their site readings and aligned turrets and guns with the aiming stake. On Dunn’s order, they fired one test round per gun. Ellis watched the fall of shot from the cliff and called in the corrections. The guns adjusted slightly, then “B” Squadron let loose with three rounds per gun at a range of five thousand yards. The salvo fell within thirty yards of the buoy, the closest of the day and a result that tremendously impressed Brigadier Sparling and everyone else present. The Sherman was proving to be a versatile tank in the hands of a well-trained crew. Sparling was so inspired that he wanted to try the Hussars’ indirect shooting skills on a more productive type of target: the Germans.

On March 1, orders came for “B” Squadron to repeat its display of gunnery skill on a major road junction near the enemy-held village of Tollo three days hence. The next day, Robinson asked 5 Armoured Brigade headquarters to up the ante and allow the whole regiment to join in the shoot. 1st Canadian Survey Regiment laid out and plotted a position big enough for the forty-eight tanks of all three squadrons and the R.H.Q. troop even before permission was received. The artillery survey party expertly hammered pegs into the earth on which each tank would line up to shoot. The fire position was well within German artillery range, so the position had to be prepared carefully so as not to arouse suspicion and fire. The longer days and sunshine of Italy’s early spring began to dry the ground, making it possible to drive all three squadrons into the firing position, which they assumed at the end of March 3. Brigadier Sparling secured the services of a British Royal Artillery Air Observation Post spotter aircraft for the next day to fly over the target area and adjust the forthcoming shoot.

“C” Squadron Shermans in position waiting for orders to fire on the Tollo Crossroads, March 4, 1944.

LAC PA-193902

Since the end of the Battle of Ortona two months before and the shifting of the Canadian mission there to the defence, there had been little news to report to the folks back home. In that light, the “Tollo Crossroads” shoot became big news, drawing out a substantial contingent of Canadian war correspondents, including New Brunswick’s own Lloyd Moore, former 8th Hussar turned sound recording technician for the C.B.C., and other interested observers.

The morning of March 4 dawned clear and bright, and flying conditions were excellent. The air observer team arrived to sort out frequencies and to net in with Lieutenant Miller’s signals tank and Major Bob Ross’s R.H.Q. command tank. The shoot started at noon. Each squadron fired test rounds to start. The spotter plane passed back corrections and ranged each one in on the target. With an efficiency that bespoke of Hussar eagerness and excellent gunnery standards, all squadrons ranged in on target in minutes. At 1215, Bob Ross ordered fifteen rounds gunfire. It was a historic moment for the 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars. Their first shots fired in anger were 720 rounds of 75mm high explosive, spit fast from the muzzles of forty-eight tank guns lined hull to hull, crashing down furiously around German positions at the Tollo Crossroads in less than two minutes. For all Canadian units on the Adriatic front, long used to suffering the wrath of German shelling with no payback, it was a glorious lunchtime treat. The Hussars’ War Diary records: “the Air [Observation Post] reported excellent results on target. He said it was ‘the most beautiful sight I have seen in a long time.’ Dense clouds of smoke rose from the target area.”

The next day, the sunshine disappeared and rain and wet snow brought the mud back in full force. The weather provided good cover, though, because it was time for the 8th Hussars and 5 Armoured Brigade to vanish from the front. Crawling out of their muddy camp onto coastal Highway 16, the Via Adriatica, they moved south to join the deception and prepare for the great spring offensive. Their next appointment at the front line would take place under the gaze of the infamous ruined Abbey of Monte Cassino, in the Liri Valley.