Chapter Five

To the Gothic Line

In early June 1944, after victory in the fourth Battle of Cassino — or the Battle for Rome, as it is sometimes called — the 8th Hussars and all of 1st Canadian Corps were pulled from the line. The first Sunday after they came out, the regiment held a memorial service for their ten comrades lost in the Liri Valley. A few days later, they moved back to the upper Volturno Valley to rest and prepare for the next phase of the campaign. General Alexander had something special planned for the Canadians. He wanted the Canadian Corps, and another British Corps, fresh, at full-strength, and specially trained for the decisive battle on the Gothic Line at the next major German defensive position to the north. The decision proved highly beneficial for 1st Canadian Corps, and especially for 5th Armoured Division. The two month rest enabled them to think carefully about the combat lessons of the Liri Valley and how they could continue adapting the machine to make it an ever-more-efficient war-winning tool.

Leadership change came quickly. 5 Armoured Brigade’s commander, Des Smith, went to 5th Division headquarters to replace the brigadier, general staff, and to tighten battle management. The Hussars were sorry to see Smith leave but happy his place was taken by Brigadier Ian Cumberland, who had shown his ability in leading the Governor General’s Horse Guards in the Liri Valley. The 8th Hussars were destined to work ever more closely with 11 Infantry Brigade, so changes at that unit would become perhaps even more important. Its commander, Brigadier Snow, was replaced by Ian Johnston, the able and combat-experienced former commanding officer of the veteran 48th Highlanders. The three infantry battalions in the brigade also got new commanders, all majors who had also proved their value in the Liri Valley and were no strangers to the 8th Hussars. The stage was being set for the most efficient tank-infantry partnership yet achieved.

The division also got an extra engineer squadron, another field artillery regiment, and more infantry. That summer, each of the Commonwealth armoured divisions in Italy created an extra infantry brigade. In the Canadian Army, heavy casualties in Italy and Normandy and a declining replacement pool made trained infantrymen a precious commodity. 5th Division’s extra brigade was formed by taking away 5 Armoured Brigade’s motorized infantry battalion, the Westminsters, and converting the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards’ armoured recce regiment and the 1st Light Anti-aircraft Regiment into infantry.

8th Hussars load up for “swim parade” at Mondragoni on the Tyrrhenian coast, June 1944.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

Once back at the upper Volturno River, 1st Canadian Corps again disappeared from German view to keep the enemy guessing about where they would appear next. As they rested and reorganized, Lance-Sergeant Don Carter was decorated with the Military Medal for his heroism in rescuing Temple Lane at the Melfa. The terrain around their new home was similar to what they expected to encounter at the Gothic Line, and the 8th Hussars got down to experimenting how to attack across the rivers and ridgelines of the northern Apennines with their new mixed force of tanks, infantry, artillery, and engineers. The already-close bond between the Hussars and 11 Brigade grew even stronger in the Volturno Valley. Each squadron worked closely with the infantry battalion it was assigned to in the coming operation. “Frenchy” Blanchet put “A” Squadron through new training with the Perth Regiment, now commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Bill Reid. Howard Keirstead and “B” Squadron kept their close affiliation with the Cape Breton Highlanders. The relationship improved tremendously when confirmation arrived that Major Boyd Somerville, who had taken over temporarily from a weary Lieutenant-Colonel Weir during the trying days at Ceprano, was to take official command. Temple Lane’s injuries prevented his return to “C” Squadron, so newly promoted Major Clifford McEwen took over and ran the squadron through new and improved drills with Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark’s Irish Regiment of Canada.

Corporal Harold Skaarup (front row, third from left) and his troop from “A” Squadron near rest camp, July 1944.

Hal Skaarup Collection

It was not all training through June and July 1944, but also a time to rest the Canadian Corps to recharge it mentally and prepare it for the coming great battle. That summer, many 8th Hussars saw something of Italy’s beauty, culture, food, and wine, and finally had a chance to bask in the warm sunshine the travel brochures seemed to have lied about. In between training, routine beach days were laid on at Mondragoni, near the mouth of the Volturno, a fifty-kilometre drive from camp. Also, leave passes were granted for every officer and man to travel some place for an extended vacation. A great many went to Rome, which had been spared by the fighting in June. Indeed, for many backwoods New Brunswickers, wandering the imperial Roman forum, sitting in cafés, and attending mass with the Pope at St. Peter’s was the experience of a lifetime. Some went to seaside resorts near Salerno and the Amalfi Coast, on the western shore. Others travelled to the Adriatic coast near Bari, where “Frenchy” Blanchet and “Sted” Henderson found peace in the midst of war by renting a small sailboat.

The Gothic Line, Germany’s last and most vital line of defence in Italy.

Mike Bechthold

The summer peace could not last. At the end of July, the Hussars assembled and made ready for the drive north. In 1944, no superhighway bypassed Rome, and all roads did indeed lead there. On August 1, those who had not visited Rome got a taste as they all passed through. Along the way, they saw more evidence of Allied labours in the Italian campaign, passing hundreds of wrecked German vehicles shot up by Allied air forces during the enemy retreat north of Rome in June. From there, the convoys swung on to the ancient Via Flaminia (Highway 3) and into Umbria. On Friday, August 4, Major Blanchet halted the tracked vehicle convoy overnight in the main piazza of Terni. As in so many Italian towns, Saturday in Terni is market day, and crews awoke to find themselves surrounded by a crowd in the hundreds. The War Diary recorded “many scenes of partly dressed Hussars rushing around trying to find their clothes while the civilian population gaped and tittered.” Life in this part of liberated Italy was returning to normal. but the march to war had to proceed. That night, the regiment drove on up the excellent two-thousand-year-old Roman-built Via Flaminia to Foligno.

At Foligno, the 8th Hussars halted for a week. They got their first briefings on plans for the great offensive planned for the Gothic Line, and ran through more tank-infantry river-crossing drills. The battlefield awaiting them further north was laced with rivers draining out of the high Apennines to the sea. German defences always made use of rivers as natural anti-tank obstacles, so all of 5th Armoured Division continuously refined solutions to river defence problems. All hands were committed to avoiding another Ceprano.

Foligno is tucked away in the Apennine foothill country of Umbria just south of Lake Trasimeno and west of the mountainous spine that runs down the Italian peninsula. Orders arrived at Foligno for Hussar tanks to cross the spine secretly on a new tank road opened days before by 5th Division’s engineers. Once safely on the other side, the Canadian Corps would assemble near the town of Jesi, just inland from the port and airfield complex around Ancona.

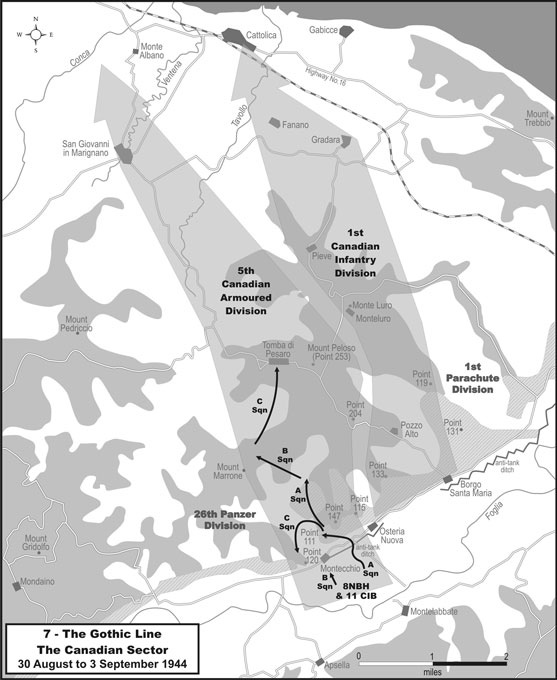

Their mission was similar to the Gustav Line offensive, but even more difficult. The plan presented to Lieutenant-Colonel George Robinson and the 8th Hussars’ officers at Jesi on August 23 placed them under command of Brigadier Ian Johnston’s 11th Infantry Brigade. A British corps would attack on their left and a Polish corps on their right. 1st Canadian Corps would attack in the centre, with 1st Infantry Division leading the charge into German outpost positions in front of the Gothic Line. In the event the Germans broke and ran, 1st Division would keep on going right through the empty concrete and steel defences of the main Gothic Line. If the Germans were unable to man those defences, 1st Division were to clear a safe bridgehead through the minefields, barbed wire, and fortified gun positions so that 5th Armoured Division could pass through and chase down the enemy. The far more likely scenario, however, was that German reinforcements would rush forward to man the main defences. In that case, both Canadian divisions were to attack together, blasting their way through the defences to seize the high ground dominating the Gothic Line in the area. Once on the summit, forward artillery observers and air controllers, using powerful radios, would bring down a storm of artillery, air strikes, and even naval gunfire from Royal Navy destroyers and gunboats upon the enemy rushing in from all corners to restore the ruptured Gothic Line.

“Q” Troop, H.Q. Squadron at Foligno, central Italy, with beret badges and all insignia removed during the secret march to concentrate Eighth Army on the Adriatic wing of the Gothic Line. (Back row, left to right): Vernon Pearson, “Junior” Campbell, Al Snelling, “Pop” Morton, Barry Chapman, Elmer Devoe, Alf Newton, “Skip” McPhee, “Mac” MacVicar, Hugh Bodman, “Available” Vail, Jim McClary, “Buzz” Wishart, Len Price, Don Ritchie, “Rolly” Simpson. (Front row, left to right): Johnny Ross, Mun Hemsworth, Shaugnessy Kirk, Doug Singer, Wendell Rae, Aubrey Dauphinee, “Fibber” Magee.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

1st Canadian Division opened its attack just past midnight on August 26. The 8th Hussars rolled out of assembly areas and followed close behind. Traffic was dense, but the lessons of the Liri Valley had taught Eighth Army and the Canadian Corps how to develop a more sophisticated traffic control system. The Adriatic coastal flats and Apennine foothills through which they were moving also had more roads than the narrow confines of the Liri Valley. In seventy-two hours, 1st Division destroyed three German battalions and powered through to the main Gothic Line. The Hussars, following up, were close enough to hear the sounds of battle and for anxious fear to gather in the back of their minds. The next day, Sunday, August 27, Padre Burnett held a morning church parade, unusually well attended on the eve of battle. Hunter Dunn wrote that, “we knew that some of us would not be at the next church parade. We hoped that our training, equipment and leaders would give us at least a fighting chance.”

The ferocity of the fighting in the outpost positions convinced British, Canadian, and Polish commanders on the scene that the Germans would man the main Gothic Line bunkers and gun positions, making a deliberate set-piece attack necessary. Therefore, on August 29, the New Brunswick Hussars took up station in the hills just behind the Foglia River valley around Monteciccardo. The plan for the coming battle against Germans fighting from prepared fortifications behind barbed wire and mines called for the regiment to fight much differently than in the Liri area. George Robinson and part of the command team co-located with Brigadier Johnston’s 11 Brigade H.Q. to serve as Johnston’s tank liaison. The battle adjutant, Captain “Ab” Shepherd, stayed in Robinson’s R.H.Q. command tank to serve as “regimental control.”

The squadrons made their way along the few roads forward over the steep, tree-covered hills of the outpost zone, each tightly controlled by military police traffic control teams. Each squadron made its way to a concentration area where it was to “marry up” and net in with the infantry battalion it had been assigned to earlier in the summer. As far as they knew, the Hussars still had plenty of time to make ready for the grand attack planned to open a few days later. But things changed on the night of August 29.

The Gothic Line, Adriatic sector.

Mike Bechthold

That night and early the next morning, infantry patrols over the Foglia River found the Gothic Line defences across Eighth Army’s front strangely quiet. More patrol reports came in from Canadian, British, and Indian units that the Germans seemed unprepared. Prisoner interrogations and German signals intercepts revealed that units manning the outpost line were decimated and unable to man properly their sections of the main line. Reinforcements were known to be on their way, but all signs suggested they had not arrived yet. Eighth Army leaders understood immediately that an opportunity existed to “gate crash” the fixed defences before the arrival of enemy reinforcements, and orders went out to get across the Foglia and onto the high ground beyond it that afternoon. Though the orders caught many 1st Canadian Corps units, including the 8th Hussars, still moving onto the heights south of the river, each squadron tied in with its assigned battalion.

Brigadier Johnston instructed his two leading infantry-Hussar battle groups to each push a rifle company over the meandering and relatively dry Foglia River bed to see if they could grab the first two hills beyond it on either side of the village of Montecchio before the Germans awoke to the threat. The remaining companies and their attached Hussar squadrons were to follow up, depending on what happened. Lieutenant-Colonel Boyd Somerville’s lead company of Cape Breton Highlanders made their way toward Point 120, left of Montecchio, while Lieutenant-Colonel Bill Reid’s Perth Regiment’s lead company worked toward Point 111, to the right of the village. As they had done in summer training, “B” Squadron made ready to move with the rest of the Capers and “A” Squadron with the balance of the Perths. The “C” Squadron-Irish Regiment battle group remained in reserve in the hills south of the river.

11 Canadian Brigade Group’s sector of Green Line 1.

Mike Bechthold

Intelligence reports proved accurate. The German regiment supposed to be defending this section of front had been destroyed. Reinforcements were on their way, however, and some of them arrived in the early morning hours. In the lowering sun of the late afternoon, a fresh panzer-grenadier battalion from 26th Panzer Division and units from 1st German Parachute Division waited until the lead Cape Breton and Perth companies were at the base of the hills before they opened fire. Enemy machine guns firing from concrete and log-reinforced bunkers shredded the leading platoons. Canadian artillery fire, including smoke rounds, plastered Points 120 and 111 to allow the survivors to escape. The isolated infantry now needed the cover of darkness and help from the 8th Hussars.

Howard Keirstead was at Boyd Somerville’s Cape Breton command post just north of the river bank when the firing started. He sent a despatch rider back to his second-in-command, Captain Bob McLeod, with instructions to bring the squadron forward to help. It was just past 1900 and there was still daylight in the sky. McLeod led the squadron up a dirt road from the river crossing to the west side of Montecchio and came to a provost or military police traffic control check point. There, they were ordered off the road. The decision to gate crash the Gothic Line had created confusion in the orders. In the late afternoon, when the Gothic Line still seemed abandoned, priority for armour on this road went to the Governor General’s Horse Guards, who had orders to break out beyond the enemy defences. Now that a fight was on in the Gothic Line itself, those orders were stale, but no one passed this information on to the military policemen. A desperate Bob McLeod jumped out of his tank and ran forward to find the Cape Breton command post and his squadron leader. When he did, Keirstead told him to get “B” Squadron up however he could. McLeod returned to collect the waiting tanks, climbed aboard his Sherman, and defiantly told the provost men that he was going through their checkpoint. Eighteen Chrysler multi-bank engines roared, and up they charged to help their Cape Breton brothers fighting desperately for Point 120.

A Cape Breton Highlander examines a “B” Squadron Sherman immobilized by an anti-tank mine.

LAC PA-2185002

“B” Squadron’s Shermans drove right up behind the Capers, only two hundred metres from the base of the hill. From there, they fired their coaxial machine guns and 75s in an effort to slacken German fire raking the infantrymen. Flares, muzzle flashes on the hill, tracer bullets, and moonlight enabled gunners to distinguish between the Cape Bretoners on the lower slopes of the steep-faced Point 120 and the German bunker complex on top of it. Keirstead ordered McLeod to go forward and connect with the Capers’ “A” Company, pinned down at the base of the hill. He had driven barely fifty yards along the road when the blast of a Teller anti-tank mine shook his tank, broke a track, and smashed a bogie wheel. Bob McLeod understood there was no time to waste. For the second time that night, he “unhorsed” and ran through the shot and shell to the most forward Capers to coordinate a fresh plan. To make it work, they needed to clear the road of mines and get tanks closer to the base of the hill. Recce Troop Leader Lieutenant Herb Snell’s mine-clearing training for the regiment over the past six months now paid off. “B” Squadron troops found and lifted a dozen Teller mines from the road. But the ground around the foot of the hill was thick with them. The Germans had carefully designed their defence here to use mines to strip tanks from their infantry. As if to emphasize the problem, a Cape Breton Bren carrier rigged as an ambulance went up on another mine. They would need more engineers to help clear a safe lane.

A second attack by “A” Company under cover of darkness was stopped in a furious crossfire, revealing just how extensive the Point 120 fortress was — smashing it would require the whole battle group attacking together. In preparation, they poured tank, artillery, M-10 Tank Destroyer, anti-tank gun, machine-gun, and mortar fire onto the German hilltop fortress. Any weapon that could throw something at the hill joined in the bombardment. By now, enough mines had been cleared that “B” Squadron could deploy across the base of the hill to put down fire on the hilltop bunkers. In the process, a second tank lost a track to a mine. The next attack went in just after midnight. The moon was high in the sky by now, outlining the crest of the hill. As the attack, by two Cape Breton companies, began, Canadian artillery and mortar fire ceased. “B” Squadron kept blasting the bunker line on top of the hill to keep the Germans’ heads down while their fellow Maritimers scrambled up the slope.

But the task proved impossible: German machine guns were too well protected in concrete for any fire to touch them. Those Capers who did crawl up the virtual cliff faced a rain of German grenades from the heights above. The survivors had to get off the hill, and the early hours of August 31 were spent covering the withdrawal. Bob McLeod remembers that, once the Capers got down off the hill, they fell back through the squadron toward the shelter of the river banks. By 0400 the tanks sat alone beneath Point 120, spitting machine-gun fire at it to cover the withdrawal. The Germans appeared to be preparing to counterattack, and McLeod feared what might happen as daylight illuminated the squadron in the open field with little cover, especially the two immobilized tanks. He ordered his own crew to “abandon my tank, suggesting they bring my whiskey. Had one shot of rum at the [Regimental Aid Post].” Thirty minutes later, Keirstead and McLeod pulled the tanks back to the river bank area and sited them with the infantry to defend their tiny bridgehead over the Foglia.

For their efforts, nineteen Cape Bretoners were dead and forty-four wounded. At first glance, the three foiled attempts on Point 120 from the front seemed like a waste of lives. However, the clifftop fortress was the strongest German position on the 11 Brigade and Hussar front. “B” Squadron and the Capers had held the attention of the German Panzer-Grenadiers manning it. By so doing, they opened the door a tiny crack for the Perth Regiment and “A” Squadron, eight hundred metres away on the right side of Montecchio.

On the other side of Montecchio, Lieutenant-Colonel Reid’s battalion had crossed the Foglia about the same time as the Highlanders. Earlier that day, Perth patrols discovered the road leading from the river to the defended hills was free of mines. The road included a bridge over a deep anti-tank ditch barring access to the hills. Apparently the road had been left open for German units manning the outpost line, but these were either dead or prisoners, and now the road lay open to the Canadians. Major Harold Snelgrove’s “B” Company advanced along it to the anti-tank ditch near the east end of Montecchio and the base of their goal on Point 111. Then, as the lead Perth platoon scrambled over the intact bridge, the Germans on Points 120 and 111 came alive. The bridge and surrounding area lay within the “beaten zone” of an MG 42 machine gun dug in and steadied on a tripod. Half the platoon was cut down by bullets in moments. Bill Reid called for an artillery concentration on the hill to screen the withdrawal of his survivors back to the river as there was no cover in their area. The Perths’ withdrawal left German machine gunners and mortarmen on Point 111 without an immediate threat to their front, so they joined in the fusillade directed at the Cape Bretoners and “B” Squadron beneath Point 120.

Reid and “Frenchy” Blanchet teed up another assault for 2230 under cover of darkness. This time, two Perth companies moved through fields beside the road, with “A” Squadron deploying between them. Once again, German machine guns and mortars opened fire at long range, but this time “A” Squadron answered the fire. The Perths attracted little German attention until they crossed into a marked mine field. Half a dozen lost feet to German anti-personnel schumines. The remainder crossed the bridge over the anti-tank ditch in short rushes. Once a company was assembled on the other side, they charged to the top of Point 111, running through the night with bayonets fixed and screaming blood-curdling cries. They climbed the hill in the moonlight under cover of a friendly and devastating rain of fire delivered by nineteen “A” Squadron 75mm guns and thirty-eight medium machine guns. At the time, Blanchet was suffering from a worsening case of jaundice, a liver and blood affliction contracted by thousands of Allied soldiers during the Italian campaign. That night, the original Hussar fought his sickness with strength of will and directed his squadron’s night action with confidence and skill. He deployed three troops and his headquarters tanks at the base of the hill to cover the shoulders of the Perths’ bite into the Gothic Line. In the process, Sergeant-Major Ralph Wallace’s tank blew a track on a Teller mine.

“A” Squadron’s “Alcatraz,” struck by a German anti-tank shell near Point 136.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

Lieutenant George Cahoon volunteered to take his troop across the bridge and up Point 111 to the Perths in the moonlight. The Perths needed Hussar firepower in case a German counterattack developed. The distance to the top was not great but the slope was steep. The hill was also covered with very dry, loose cultivated soil. The Germans had calculated that no tracked vehicle could make it up and had left no anti-tank mines or guns to cover it. But the Hussars knew how to make their Shermans climb. In minutes, Cahoon’s troop crawled to the top of the hill. They found cover in a sunken road just behind the crest, where they nestled with hulls down and only their turrets poking over the bank to fire when needed. Eighty Canadian infantrymen and four tanks now had a fingerhold on the Gothic Line.

On August 31, the picture became clearer. Point 111 was the seam between the still-arriving 26th Panzer Division and the well-established 1st Parachute Division on the right, or eastern end, of the Gothic Line. It was also the end of a long spur that reached up to the Canadian Corps’ main goal of three controlling peaks adjacent to the village of Tomba di Pesaro. Air photos and Italian resistance units revealed how the area was thick with prepared German bunkers and concrete-embedded tank turrets. The race was now on to get to that high ground before the rest of 26th Panzer arrived and finished manning it. The British Columbia Dragoons and the Perths were ordered to slip through the tiny fingerhold around Point 111 and thunder up the spur to the Tomba di Pesaro high feature. The problem was that the Germans were thick on both shoulders of the breach in the Gothic Line and they must not be allowed to interfere with the penetration. 1st Canadian Infantry Division took care of the right side, looking to settle a score with its old nemesis, the German paratroopers. The left shoulder fell to 11 Canadian Brigade and the attached 8th Hussars.

In the early morning hours, the Cape Breton Highlanders and “B” Squadron stayed put in front of Point 120, fixing German attention to their front. The Perths and “A” Squadron cleaned out the panzer-grenadiers and cemented their hold on Point 111. Brigadier Ian Johnston ordered his reserve of “C” Squadron and Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark’s Irish Regiment into the breach. The Irish marched up in the last hours of darkness. Cliff McEwen and Bill Wood were not far behind them with “C” Squadron. Their Shermans crawled out of the river bed by 0645, and thirty minutes later pulled into position beside “A” Squadron’s tanks on Point 111. There, they overlooked the right rear of the German fortress on Point 120. McEwen and Clark’s Irish planned to attack it from this weak flank while the Cape Breton-“B” Squadron battle group hammered it from the front. The Germans were not about to give up the Gothic Line without a fight, however, and brought down their own storm of shell and mortar fire onto the Canadian Point 111 toehold. Now every 8th Hussar squadron was in the fight.

Around that same time, at 11 Brigade’s headquarters overlooking the Foglia Valley, Brigadier Johnston asked Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson if he was willing to take a risk. Johnston wanted Robinson to detach Blanchet’s “A” Squadron from the Perth Regiment and drive it forward to Monte Marrone, the southwestern-most spur of the Tomba di Pesaro high feature. The move would cut the road to the Point 120 fortress and help cover the left flank of the British Columbia Dragoons, who were setting out for the centre of the high ground. Experience in the Liri Valley had taught them that pressing tanks deep without infantry was a gamble, but the whole Eighth Army Gothic Line plan depended on aggressive action. George Robinson immediately agreed, and issued orders to “Ab” Shepherd in the control tank to radio ahead to Blanchet.

Destroyed German PAK 43 88mm anti-tank gun on Monte Marrone.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

The orders arrived on Point 111 amid of a flurry of activity as tankers and infantry jockeyed into position to carry out two distinct missions, in daylight with Germans still lurking on their hill and with enemy shells crashing down around them. Captain Ron Lisson, a “C” Squadron troop leader from Sussex, New Brunswick, pulled his tank onto the hill as “A” Squadron was getting organized to set off into the blue. Lisson saw the exposed “Sted” Henderson issuing orders from his open turret hatch. The Germans were alive to the threat posed by two tank squadrons and two infantry battalions atop Point 111, and blasted them with everything they had. Concentrations of their mortar bombs killed or wounded half a company of the Irish Regiment caught in the open. Ron Lisson motioned for his friend from Moncton to get down in his hatch. The gutsy “Sted” Henderson finally did get down, but only because a sniper’s bullet struck him. “Frenchy” Blanchet’s dear friend and sailing partner was still alive, but mortally wounded. Henderson’s own crewmates took care of him while the rest of the regiment got on with the job of levering open the left shoulder of the Canadian breach in the Gothic Line.

“C” Squadron and the Irish moved off west down into a deep warren of ravines separating Points 111 and 120. Tragedy struck frequently that day. Major Ainslie Ardagh, a replacement officer from Quebec City, had been assigned to the Hussars just days before to get battle experience prior to taking over a position with the British Columbia Dragoons. His Sherman broke down on the valley floor before the Germans unleashed their fury on Point 111. He was dismounted in the open and trying to find his way to the forward Hussar squadrons when a German shell killed him.

Back on top of Point 111, George Cahoon pushed his four Shermans to the crest, where they could see north across the deep ravines and all the way to Monte Marrone. From there, Cahoon’s troop covered the rest of the squadron as it made off for its objective deep behind the German front. The lead troops under Lieutenants J.H. Lackie and Don Crawford took time to negotiate the steep descent north from Point 111. The fourth troop and “Frenchy” Blanchet’s Headquarters troop, including his rear link, Captain Doug Lewis, followed behind. In thirty minutes, they crawled down and along eight hundred metres of the narrow valley leading toward Monte Marrone, ever on the lookout for an enemy ambush. At 0910, “Frenchy” saw smoke billow from a tank in the lead troop. He also spotted the German anti-tank gun that shot it concealed in a haystack. There was no cover between his tank and the enemy gun. He hollered through the intercom to his driver to “get on that position before he swings around!” He then toggled the handset over to the radio net and told Doug Lewis to “cover me.” Blanchet and Captain Doug Lewis both put spurs to their Chrysler engines and barrelled toward the enemy. Blanchet’s gunner fired the 75 and blazed away with the machine gun. Above their heads, George Cahoon, watching, directed his troop’s fire onto the German position as well.

Graves of Steadman Henderson and Bernard McIntee in the temporary Canadian cemetery at the foot of Point 111, now the Montecchio Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

Lewis’s co-driver called on the intercom that a second “A” Squadron tank was hit and burning to their left front. It was Troop Sergeant Bernard McIntee’s tank. German infantry concealed in trenches beside them threw grenades into the hatch. Captain Lewis watched as McIntee’s crew bailed out of the burning tank only to be cut down by a German machine gun. Four Hussars went down, one dead and three wounded. Bernie McIntee was still on his feet, but he’d had no time to pull the Thompson submachine gun out of his turret when he jumped from his burning tank, so he ran at the German machine gun with bare fists.

Doug Lewis, watching the slow-motion horror, bellowed to his driver to get to McIntee. At the same time, he did not lose sight of Blanchet’s orders to cover the squadron leader’s one-tank charge to the German anti-tank gun, and his gunner and turret stayed trained on the enemy gun off to the right, spitting machine-gun bullets. Lewis gaped in horror out of his hatch as his tank thundered toward the murderous site, but McIntee was riddled with bullets. German panzer-grenadiers then emerged from their trenches with bayonets fixed. They butchered two of the wounded Hussars with steel blades and then clubbed Bernie McIntee’s head with rifle butts. The lone surviving crew member, Trooper Charlie McGrattan, an original from St. George, New Brunswick, was shot through both legs but still grabbed one of his assailants, pulled him to the ground, put his hands round his throat, and exacted retribution. Meanwhile, the noise and din of battle all around the hills and ravines had rendered the Germans oblivious to the “A” Squadron tanks charging them. When they saw the steel cavalry charge about to break over them, the rest of the panzer-grenadier platoon manning positions around the anti-tank gun threw down their weapons and thrust their hands in the air. But it was too late. “A” Squadron’s machine guns cut them down. Doug Lewis was half out of his hatch with his .38 revolver drawn. He shot one German in the head and another in the chest. When it was over, twenty-five German bodies and a wrecked 75mm anti-tank gun were strewn around them. Sergeant Bernard McIntee and Troopers George Waniandy, Eric Jackson, Hartford Cook, and Joseph Deveau were dead, awaiting recovery by the padre. German shell and mortar fire continued to crash down, giving “A” Squadron survivors no time for reflection. There would be plenty of nights in the decades to come to remember. Instead, the remaining twelve Shermans bashed ahead to the cover of Point 136, a small spur just short of Monte Marrone, reaching it without further incident, although the steep climb tested drivers.

Blanchet then ordered George Cahoon’s and Don Crawford’s troops over the top. They led off across the seventeen-hundred-metre-wide valley between Point 136 and Monte Marrone, covered by the rest of the squadron. When the first two tanks moved over the crest, German anti-tank guns on Monte Marrone and in a farm at the bottom of the valley burst into life. First one tank, then the other, Cahoon’s, was hit. Cahoon remembers, “Just as we got near the top of Point 136, Bill Bell’s tank got it. It was quite a little peak and just as we got to the top ourselves an 88 streaked by my face. [Another one] hit the turret. The tank shook like a canoe hitting a rock. We started going backwards down the hill. We bailed out as best we could.” Both tanks tumbled back down the steep slope. Fortunately, no Hussar was killed, but one man lost a leg. Sergeant Charlie Boynton got him out.

Blanchet halted his squadron on the reverse slope of Point 136 to size up the situation. Dismounted from his thirty-three-ton “horse,” “Frenchy” crawled up to the crest to survey the ground. By now, jaundice had rendered him so ill that “his face looked like a duck’s foot.” But on he climbed through sniper, mortar, and artillery fire. With map and radio in hand, he directed the 8th Field Regiment’s artillery fire onto the German anti-tank gun line and the farm in the valley below. After the smoke cleared, the squadron roared forward again, hoping the artillery had smashed the enemy’s anti-tank guns. Unfortunately, the German gun positions — which included deadly and well-protected Panther tank turrets embedded in concrete — in this powerful and deep section of the Gothic Line were too well dug in and concealed for the short artillery barrage to destroy them. The squadron found this out the hard way when Troop A Corporal Harold Skaarup’s Sherman led off over the crest. A high-velocity shell pierced the side of his hull and sliced through the lower turret, violently tearing away both of Skaarup’s feet and setting the tank ablaze. The crew heroically pulled their stricken crew commander from the burning tank and got him behind the crest just in time to be plastered by a salvo of enemy mortar bombs. Skaarup was wounded again as bomb fragments carved open his chest. Miraculously, the New Brunswicker’s heart still beat strongly in his shattered body, and his friends got him to safety, but Harold Skaarup died in hospital seven days later, on September 6.

“A” Squadron’s casualty toll was dangerously high. With his squadron reduced from nineteen to nine tanks and ammunition and fuel running low, Blanchet opted to sit tight and wait for help. If he attempted to advance his fast, but vulnerable, Shermans across seventeen hundred metres of open ground against the thick anti-tank gun screen, there would be no “A” Squadron tanks left to hold Monte Marrone. “Frenchy” Blanchet’s tanks remained tucked behind their crest, popping up in different locations to shoot at targets of opportunity for the rest of the day.

The timing of the action in the late morning of August 31 was critical. At the same time, British Columbia Dragoon tanks grabbed Point 204, the first of three peaks making up the Tomba di Pesaro high feature — the tiny crack the Canadians had forced in the Gothic Line the night before was growing. The New Brunswick Hussars and British Columbia Dragoons had managed to slip through a weak spot at the divisional boundary between the still-arriving German 26th Panzer and 1st Parachute Divisions. But Canadian victory was not yet certain. The next twenty-four hours would be a race to see if the Canadian Corps could strengthen its isolated footholds before German reinforcements arrived to counterattack. The outcome depended on blowing a bigger hole in the main Gothic Line defences still holding out in the Foglia Valley. That meant taking out the Point 120 fortress and opening the road up to “A” Squadron, a process that actually started simultaneously with Blanchet’s drive deep into the Gothic Line. As “A” Squadron fought through the ambush site, the lead Irish company attempted to attack the Point 120 fortress from the right. They hit a wall of German fire, indicating the enemy had no intention of giving up his position. Major Cliff McEwen and Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark then put together a most extraordinary plan. McEwen, his rear link, and two tank troops would edge to the left side of Point 111, where they could put fire down on the Point 120 fortress. Second-in-command Captain Bill Wood would take his tank and the remaining two troops in a wide sweep down into the valley with another Irish company to attack the German strongpoint from behind.

Around mid-morning on August 31, McEwen’s half-squadron opened fire on Point 120, adding their weight to an already intense Canadian artillery barrage. Down below on the river flats, “B” Squadron and the Cape Bretoners once again poured fire at the strongpoint from the front. But the bunkers on the steep-faced hill were too deep to be defeated by fire alone. Someone had to go take it. With a storm of shot and shell engulfing the fortified hilltop and behind a screen of smoke shells, one Irish company began crawling on hands and knees through the scrub between Points 111 and 120. Meanwhile, the other half of “C” Squadron charged around behind Point 120. An Irish company followed in a wide flanking march made deliberately so the Germans could see they were being cut off. Captain Ron Lisson covered Lieutenant Ray Neil’s troop, which sped down into the valley at full speed. Bill Wood’s headquarters tank was right behind them. The Germans, apparently alarmed by this new threat from tanks and infantry closing in from their rear, turned their weapons — including a pair of self-propelled 88mm anti-tank guns from a location a thousand metres to the north — toward the “C” Squadron charge. Several tanks from the rest of the squadron answered, silencing the German fire and sparking a heated radio argument over who had scored the winning shot.

“C” Squadron and the Irish Regiment pulled off a textbook combat team assault. Every German in the Point 120 fortress was either pinned down or trying to turn his weapon to face the nine “C” Squadron tanks and the Irish company closing in behind them. Lisson’s and Neil’s troops covered each other by fire and movement to within point-blank range of the trenches and bunker on the back side of Point 120. Bill Wood watched from a few hundred metres behind them. “I recall Neil placing his tank astride one of the trenches that ran back from Point 120. As the Germans tried to escape he machine gunned them until they surrendered.” Wood and McEwen also directed artillery fire onto the now clearly visible German positions.

At the same time, the Irish company that had begun crawling on their bellies down from Point 111 under Hussar cover fire finished their stealthy climb up the east face of Point 120. They arrived right underneath the Germans’ noses and went to work clearing enemy machine-gun bunkers with bayonets, boots, and grenades. Lisson and Neil saw the Toronto Irish working westward across the crest and fired their own creeping 75mm and machine-gun barrage in front of them. Just after noon, 2nd Battalion of 67 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment surrendered, and 117 survivors emerged from their concrete, steel, and earthen positions under white flags and turned themselves over to the Irish. Neil’s troop rounded up thirty-five more at the back end of the position. Thus, a whole battalion was not just defeated but completely eliminated from the German order of battle. The left shoulder of the wedge in the Gothic Line was now secure. It was time to push more Canadian troops into the breach.

Twenty-four hours of hard driving and fighting had drained fuel tanks and emptied ammunition bins. The three squadrons were spread thin and deep into the foothills north of the Foglia Valley. Headquarters Squadron had anticipated the problem, however, and Major J.B. Angevine coordinated the move of the Hussars’ trucking supplies to the Foglia River bed, where the unstoppable Jack Boyer and his “A” echelon refuelled and rearmed tanks wherever they happened to be. “B” Squadron, still positioned on the valley floor, was easiest and first to “bomb up.” They made their way back to the river a troop at a time. The other squadrons were more of a challenge, as it was impossible for them to pull back for a laager resupply. In the thick of the intense morning battle, Boyer drove north over the river in a jeep in search of a location for a forward supply dump. The Germans still owned much of the high ground overlooking the Foglia Valley and tried to block it with a wall of shells. An open jeep was no place to stay alive, so Boyer abandoned it and kept going on foot until he found a protected enclave beneath Point 111, four hundred metres behind “C” Squadron. He got word to his truckers to start hauling jerry cans and ammunition to the dump.

It was a harrowing drive. Lance-Corporal Felix Boudreau from Beresford, New Brunswick, drove one truck laden with boxes of 75mm high-explosive shells. Four German shells burst close enough to riddle the truck with shrapnel, smash the windshield, and puncture Boudreau’s thigh. He patched up the hole in his leg, brushed away the smashed windshield, and drove on to the forward ammo dump. Once unloaded, instead of reporting to an aid station, he drove back across the fire-swept valley for another load. Boudreau’s devotion earned him a Mentioned-in-Despatches for bravery.

While his truckers dumped supplies, Boyer climbed the hills scouting out covered meeting places. He arranged with “C” Squadron to send one troop at a time to these safe locations to meet Recce Troop Honeys ferrying ammunition and jerry cans of fuel. Blanchet sent a tank back for supplies. Boyer answered his call and set up a new safe area behind Point 136. “A” Squadron’s tanks slipped down one at a time to replenish, and in that way kept guns firing on Monte Marrone all afternoon. This day was the greatest test of the war for the “A” echelon, and Jack Boyer won the Military Cross. The citation records that “he distinguished himself by his complete disregard for his own safety as he maintained liaison with the squadrons which were all under very heavy shell and mortar fire.”

11 Brigade’s infantry battalions also needed a few hours rest to draw water and ammunition. The late summer sun was intense and the air dry. Sweat coated every man, making the great clouds of dust cling to their skin like paint. Inside the tanks, the temperature rose to an unbearable level, but their crews endured. By late afternoon, the “B” Squadron-Cape Breton Highlanders battle group began moving up to relieve Blanchet’s beleaguered force. They had hardly started when the radio reported a German counterattack forming at Tomba di Pesaro. Every Canadian soldier already inside the Gothic Line dug in and made ready to prevent the Germans from recapturing the high ground they had won so far. But the attack never came. Although this was the second such call to come that afternoon, these were not false alarms — German tanks and infantry were indeed massing, but each time they were detected by observers in British artillery spotter aircraft, who called for the emergency concentration of every field, medium, and heavy gun within range of the target. The German counterattacks were obliterated before they could begin.

Darkness would put an end to the air advantage, though, and “A” Squadron would be in serious trouble if left alone after the sun went down. Morale sank as exhaustion and thirst grew worse. Help could not have been more timely. As the last daylight faded and the lonely band of “A” Squadron crews contemplated how to resist a night attack by German infantry, the Cape Breton Highlanders finally arrived, somewhat rested and recharged. Infantry companies took control of the high ground all around them. “B” Squadron was not far behind, driving forward under a bright moon. Keirstead’s Shermans took up position in line, with the Highlanders as their anti-tank defence.

Brigadier Johnston ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Somerville not to stop at Point 136, however, but to use the cover of darkness to cross the small valley and take Monte Marrone. The whole Canadian command chain wanted to take advantage of German confusion and get control of the high ground before the rest of 26th Panzer Division arrived. And so the Highlanders infiltrated down into the valley in the early hours of September 1 under cover of “B” Squadron’s guns. There was no need to fire, though. The Capers began digging in by 0300.

At dawn, Howard Keirstead brought his squadron up to thicken their new positions. Co-drivers dismounted to guide the Shermans up the slope and into fire positions. As the sun rose, the Germans realized their hold on the Tomba di Pesaro high ground was slipping, and they tried to drive the Canadians from Monte Marrone with fire from every type of weapon in their arsenal. Intense artillery, mortar, machine-gun, and sniper fire rained down on the long ridge from the higher ground a thousand to fifteen hundred metres north around Tomba di Pesaro. High-velocity anti-tank shells shrieked across the steeply rolling clay hills before slamming into two Shermans of Lieutenant Bill Spencer’s 3 Troop. Black smoke billowed from both as they caught fire and burned. Anxious squadron mates counted their shaken brothers, some of whom were wounded, as they bailed out. They watched one Hussar after another scramble from smoking hatches until the number reached eight. There should have been ten. Corporal Lorne Fraser of Tabusintac, New Brunswick, and Trooper William Harper from Black River Bridge, New Brunswick, were killed.

The Hussars and Cape Bretoners tucked in tight behind the crest of Monte Marrone and called artillery fire down on the Tomba di Pesaro high ground. They were not the only ones to do so. Around the same time, fifteen hundred metres east, 5th Canadian Armoured Division’s main force prepared to attack the Tomba di Pesaro high ground from Point 204. Little did they know that five German battalions backed by tanks, artillery, and self-propelled guns were marshalling in Tomba and around Monte Peloso for a massive divisional counterattack. The Germans wanted Point 204 back. With the Hussars and Capers on Monte Marrone having a clear view of the right shoulder of the German forming-up area, as well as their artillery positions, the morning of September 1 turned into a giant long-range fire fight. The Germans were caught in the open as Lord Strathcona’s Horse and Princess Louise Dragoon Guards waded into them on their front and 8th Hussar tank shells ripped into their open right flank. German tanks and self-propelled guns gathering to support the counterattack southeast to Point 204 turned southwest to duel with the Hussars at a range of over a thousand metres. A high-velocity 75mm German shell glanced off Captain Bob McLeod’s main gun. He “reamed it out with an [armour-piercing round] and kept on firing.” “B” Squadron’s remaining Shermans cut loose on the German vehicles, lighting up a Panther and a self-propelled 75mm gun.

From Monte Marrone, Hussar gunners could see and hit targets in the south and east end of Tomba di Pesaro and were able to cut the road from the town to the battle raging between the German parachute battalions and the rest of 5th Division. But a short spur descending south from the Tomba di Pesaro shielded some of the village, as well as the main road leading into it from the north and the German gun positions sheltered behind it. At 1000, in the middle of the dramatic battle against the paratroopers in front of Tomba di Pesaro, Howard Keirstead asked Bob McLeod to drive his troop a thousand metres down the north face of Monte Marrone to a farm that lay at the end and just beyond the southern spur. From there, McLeod could put down fire on the enemy rear. McLeod and his crew commanders studied the farm and the ground leading to it through binoculars before making their attempt. McLeod said afterwards that they charged out “in the big wheel, blasting and machine-gunning everything.” But the quick fix of blasting his damaged main gun back open with an armour-piercing round apparently had not completely solved the problem, and a 75mm high-explosive round jammed like a time bomb inside the damaged bore. McLeod, though, reported his dilemma nonchalantly: “Half charge stuck. Could get it neither in nor out. Cleared it in about five minutes and second half charge worked. Moved on.”

A hidden German anti-tank gun then opened fire off to the west from the British 5th Corps sector, but missed. Corporal W.H. Sheppard spotted the flash, swung his turret left, and fired. Sheppard did not miss. McLeod’s little band of four Shermans kept on going toward the farm. A burst of machine-gun fire at the house produced white sheets from the windows — the farm was full of Italian civilians. McLeod dismounted a few troopers with Tommy guns to make sure no Germans were hidden nearby. Once the area was clear, the tanks moved up to where they could see into the rear of Tomba di Pesaro two kilometres away. Their long-range gunnery skills learned back at Ortona once again paid handsome dividends. McLeod’s gunners shot up everything in the village they could see. They fired until ammunition ran out just after noon, then Keirstead ordered them back to the relative safety of Monte Marrone and replaced them with another troop. Just as the relief began, a German infantry platoon was spotted making their way from Tomba di Pesaro to take back the troublesome farm. Hussar machine guns knocked them down before they got close enough to strike. As McLeod’s tanks made their way back to Monte Marrone, two more German anti-tank guns fired from the north and south. Turrets swung left and right, firing off the last rounds saved for the drive home. Both German guns were hit and destroyed, but not before one of their shells glanced off Bob McLeod’s turret. “After two hits on tank, told Howard Keirstead I was born to be hanged not shot!”

High-velocity shells continued whistling around the area, and more German armour took up positions to neutralize the Hussar threat from the south. By now, “B” Squadron had been reinforced by a troop of M-10 tank destroyers from the 98th (Bruce Peninsula) Anti-tank Battery. Their higher-velocity 3-inch guns joined Hussar guns in shooting up another Panther and two STUG III armoured assault guns. Forward observers and an Auster observation aircraft directed artillery fire onto everything else they could see. There was certainly much to shoot at. Around mid-day, the main 5th Division assault struck northwest from Point 204 and collided head on with the German parachute division’s counterattack force. Most of the paratroopers were caught in the open by fire to their right and by Canadian artillery raining down from above. Three battalions of 4 German Parachute Regiment virtually ceased to exist. When Cliff McEwen’s “C” Squadron and Clark’s Irish Regiment moved up to relieve the Capers and “B” Squadron on Monte Marrone, they ran headlong into a fugitive German company attempting to escape the Canadian trap. At first, the Germans tried fighting their way out, but after a number were cut down by “C” Squadron machine guns, seventy put their hands in the air.

German defences in the Canadian sector of the Gothic Line were destroyed. The enemy had lost too many men to hold on to the northern end of the Tomba di Pesaro high ground without being massively reinforced. When the Irish and “C” Squadron carried the attack into Tomba itself in the late afternoon, they found it all but abandoned except for a few snipers. The Germans left behind hundreds of their dead.

The 8th New Brunswick Hussars had played a central role in breaking the Gothic Line, and had much in which to take pride. Several tanks had been damaged by mines and shells, but given the amount of German fire thrown around Tomba di Pesaro, Hussar casualties had been mercifully light, which made what was about to happen behind Monte Marrone all the more bitter.

That morning, as the raging battle moved northward, Padre Bill Burnett took advantage of the opportunity to recover “A” Squadron’s dead. He and a work party of six Hussars in a Recce Troop Honey drove to the ambush site from the day before, a thousand metres behind the fight on Monte Marrone. With German shells falling around them, Burnett’s group gathered the bodies together in a temporary burial site and marked their location, so that the remains would be safe from further disturbance or from being lost forever amid ongoing shelling. During the Great War, shellfire and mud had stolen away the remains of many of the dead, condemning families never to know what had happened to their loved ones. During the Second World War, in contrast, every effort was made to recover remains and provide closure for families.

The burial party was just about to head for the rear when the padre spotted a German lying dead on barbed wire. The man of the cloth insisted they treat enemy remains with the same care as their own. Moments after the Honey stopped and the group dismounted, two German shells burst in their midst. All seven men were blown down and riddled with shrapnel. Troopers William Rutherford and Norvin Crawford died instantly. Lance-Corporal Steward Duffus and Trooper Edgar Shirley succumbed later that day to their wounds. Others died later. Don “Mow-em-Down” Rodgers and Johnny Hay from Chipman, New Brunswick, were among those badly injured but alive. So, too, was Bill Burnett. The blast tore off two fingers and a thumb, smashed his arm, and ripped open his stomach. An 8th Field Regiment officer arrived on the scene and began administering first aid. Burnett insisted that the other wounded men be attended to first. Weeks afterward, as he lay in hospital on the edge of death from the stomach wound, he was awarded the Military Cross. The citation reads: “Throughout this action Captain Burnett displayed an example of gallantry and devotion to the spiritual and physical welfare which was far above the normal call of duty.”

In their greatest test under fire so far, in the desperate, swirling battle for Tomba di Pesaro, the whole of the 8th Hussars performed beyond the normal call. Symbolic of the regiment’s devotion to duty on the Gothic Line, one old Hussar had to step down: Major “Frenchy” Blanchet’s jaundice had nearly overcome him. When Howard Keirstead relieved his squadron late on August 31, “Frenchy” was shaking from fever and exhaustion. He had fought his squadron skilfully and professionally, but had pushed beyond his body’s limit in the process. Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson relieved him and sent him to hospital.