Chapter Six

Reckoning at Coriano

As a leader of men, Lieutenant-Colonel George Robinson had his work cut out for him on September 2, 1944. “Tim” Ellis viewed Robinson as one of the finest officers he had ever known. The commanding officer knew all his officers and addressed them by their first name, and knew most of the men. He was a man who led by example and earned the trust of the Hussars by asking for their input. Now the trust they had in each other would be tested in the extreme.

The regiment was shot up, exhausted, and thinned by casualties. But the enemy was in far worse shape. German units that had manned the Gothic Line were smashed. Units not shattered during the past forty-eight hours formed rearguards to cover the exodus northward of mangled German battalions and vehicles. At dawn the 8th Hussars came back under command of their own Brigadier Ian Cumberland’s 5 Canadian Armoured Brigade. The moment seemed ripe to give chase to a beaten enemy.

September 2 was a day of rest and vehicle repair and replenishment to get ready for the grand pursuit. Replacements also had to be found for the dead and wounded. Captain Lloyd Hill was promoted to acting major to fill the void left in “A” Squadron. Hunter Dunn was made acting captain and the new squadron rear link. “Tim” Ellis was made acting major to take over Headquarters Squadron. “C” Squadron had lost the steady presence of Bill Wood, who had been evacuated after his foot was badly jammed and slashed in his turret during the charge on Point 120. Ray Neil was made acting captain to replace him in squadron H.Q. Harry Fleming had smashed his ankle, and he too was headed to a hospital. Other injured Hussars went with him to the rear, their places filled by new men from the Canadian Armoured Reinforcement Unit in Italy.

September 2 was also filled with uncertainty and anxious hope. According to the original plan, the Allies were to defeat the Gothic Line defenders and meet the enemy main force somewhere to the north as it rushed to stop an Allied breakthrough. The Canadians’ victory on Tomba di Pesaro looked so complete, however, that it seemed likely the Germans might start to abandon Italy completely. On that same day, victorious Allied armies were racing across northern France and Belgium and closing in on the Dutch and German borders. Hitler’s Germany appeared about to collapse. In fact, Germany shifted bomb-shattered munitions factories into overdrive and called up protected skilled workers to rebuild their armies sufficiently to stay in the war for one more suicidal year. But no one on the Allied side could see that in early September 1944 — in fact, quite the opposite was believed. If there was any chance of pushing over the rickety Nazi house, it must be taken.

In Italy, Eighth Army and 1st Canadian Corps rushed every last tank to the front and made ready for a grand steel cavalry charge. By the end of September 2, Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson had new orders. That night and early the next morning, 5th Division was to climb down the north face of the Tomba di Pesaro and cross the almost-dry Conca River. The 8th Hussars were to cross into the Conca bridgehead and ride hard for the Marano River toward Rimini. If the Germans were, in fact, commencing an evacuation of Italy, they must be run down and caught.

Canadian resupply convoy traversing the Tomba di Pesaro high feature after the fighting shifted north to Coriano Ridge.

LAC e-008303220

In the early morning darkness of September 3, the regiment assembled short of the Conca River’s nearly dry gravel bed. Infantry from the newly created 12 Canadian Brigade secured a crossing with Shermans from the Lord Strathconas. Among them was the 89th Anti-Aircraft Battery, from Woodstock, New Brunswick, converted to infantrymen. At dawn the 8th Hussars crossed the river looking to join companies of the Westminster Regiment assigned to accompany them for the drive on Rimini. Squadrons shook out around the roads leading northwest to Misano, anxiously awaiting their turn to lead the race. The wait grew longer than expected. Up ahead, lead units of 1st Canadian Corps bumped into sizable German units defending houses and hamlets across the Misano Ridge. It was not clear if this was a new German main battle line or a strong rearguard. The Hussars kept waiting, within earshot of a vicious fight, for their chance to help.

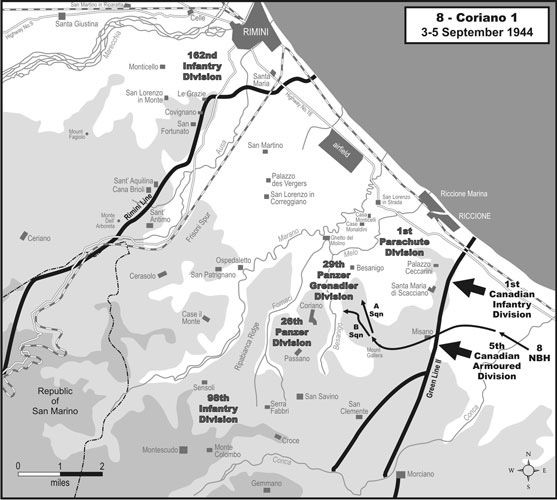

First Battle of Coriano.

Mike Bechthold

An impatient George Robinson jumped from his tank and went forward to find out what was going on. “C” Squadron was furthest forward, preparing to take the lead. Cliff McEwen was also dismounted, looking for the Westminsters, who were caught up in the sharp fight for Misano Ridge. Nonetheless, the two officers worked out a plan and headed back to their tanks. Around them fugitive German pockets were still retreating north from the broken Gothic Line — as in the Liri Valley, armoured pursuit battles meant finding the enemy not just in front but anywhere. Robinson was some distance from his own Sherman when a Panzer IV crashed through a hedge beside him and onto the road. The enemy tank crew did not see or care about the Hussar colonel diving for cover in the ditch beside them. Instead, the German tank throttled up the road at high speed, making for Misano. It drove a hundred metres down the road before “C” Squadron Shermans plastered it with shells and knocked it out. Robinson remembered, “I was just recovering, having overcome my shaking, and was starting back for my tank when to my amazement a short-barrelled 88 started coming through the hedge in the same place as the previous one. It also had a German tank on the end of it.” Robinson dove back into the ditch just as the second tank, actually an older-model Panzer IV, turned onto the road right beside him. Immediately, a “C” Squadron high-explosive round slammed into the enemy tank, showering the commanding officer with debris. McEwen’s squadron now was fully alert to the presence of Germans all around them and blazed fire at anything that moved. Every time Robinson emerged from his ditch, a burst of coaxial machine-gun fire sent him back to the bottom.

Eventually, however, I managed to get out of the ditch and saw a tank across the road, about 75 yards away. I started to run towards it and the thing that impressed me most was that his guns were trained right on me and at the back of the tank was Cliff McEwen with his helmet half on, pounding the turret with his fists and shouting “shoot the bastard, kill the s.o.b.” I thought Cliff could not possibly be referring to me as he had never spoken in such disrespectful terms before. However, not taking any chances, I shouted at him “you bastard, if you shoot me I’ll break your Goddamn neck.”

Luck was on the Hussars’ side that day. Had the two German tanks made it up the road, they would have pounced from behind on the Strathconas and Westminsters fighting on Misano Ridge.

After this short burst of excitement, the Hussars waited anxiously. Up ahead, it took the Allies all day to fight through and around the German blocking force on the higher parts of Misano Ridge. Even then, German paratroops manning the lower slopes and seaside resorts covering Highway 16 on the Adriatic coast refused to give up their coastal defence pillboxes and fortified houses from which they were checking 1st Canadian Division. Casualties mounted on both sides, a telling sign that the Germans might not be in headlong retreat from Italy after all. But the picture of enemy intentions was still unclear.

That night, orders were issued and plans made for the 8th Hussars and the Westminsters to advance north together beyond Misano Ridge and outflank the blocking force along the coast. They were to fight their way as quickly as possible to the next physical obstacle on the Canadians’ path to Rimini: the Marano River. The force planned to make use of a ridge spur running north from Mount Gallera, the highest point on Misano Ridge, to the farm village of San Andrea-in-Besanigo. Their first goal was a medieval fortified mansion, or palazzo, at the north end of the spur. From there, they could overlook and cover crossing sites over both a stream called the Melo and the Marano River. If they made it that far without much German resistance, they were to bounce across the Melo and the Marano. But the palazzo was four thousand metres away, and no one was certain how many Germans overlooked the path.

In the pre-dawn darkness, the Hussar-Westminster battle group formed up behind the crest of Misano Ridge. At 0600, Captain Herb Snell’s Recce Troop led off, followed by “B” Squadron, then “A” and the remainder of the regiment. The Westminsters followed behind in armoured carriers and trucks, ready to dismount if a substantial enemy force was met. The lead Honeys and Shermans climbed over bald, grass-covered Monte Gallera and descended the spur toward San Andrea. A thousand metres to the left, in 5th British Corps’ area, ran a parallel spur slightly higher than the one the Hussars were driving. Midway along the higher ridge, on a slight rise and plateau, perched the farm town of Coriano, which also gave its name to the ridge. Behind the Coriano Ridge rose an even higher ridge line, with stone hilltop villages, castles, and the edge of the northern Apennine Mountains. The 8th Hussars did not know if any Germans lurked on the high ground to their left. Their chief concern, in any case, was enemy units reforming on a defensible line on the Marano River. Reports then came from neighbouring British units on the Canadian left indicated that 1st British Armoured Division tanks were approaching Coriano. As September 4 dawned, four British tank regiments and the 8th New Brunswick Hussars were riding hard down the ridge spurs toward the Marano River, aiming to break what they suspected might be a strong German rearguard protecting the high ground south of it.

Thirty minutes after the Allied tanks had crested the Misano Ridge startline, the Coriano strongpoint came to life. The shooting started with Recce Troop and “B” Squadron taking on a few scattered Germans on the San Andrea spur itself. In this action, No. 1 Troop leader, Lieutenant Wally Manley, directing his tank from an open hatch, took a bullet or fragment to the jaw. Major Keirstead dispatched Captain Bob McLeod from his H.Q. Troop to take over Manley’s tank and the troop. Sergeant Keith Fisher took McLeod’s place in “B” Squadron’s rear link tank. In minutes, Recce Troop and “B” Squadron had fought their way successfully northward along the San Andrea spur. Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson then ordered Lloyd Hill to take “A” Squadron over Misano Ridge and join “B” Squadron’s fight. As they rode down the San Andrea spur, the fire from German tank, self-propelled gun, and anti-tank guns in Coriano, a thousand metres away, thickened. An armour-piercing round punched through the front left side of Lieutenant J.H. Lackie’s tank. Everyone bailed out but the co-driver, whose hatch was blocked by the turret, which was traversed slightly right. Hunter Dunn watched what happened next. “I saw Trooper Hills climb back onto the tank, jump into the gunner’s seat, and traverse the gun away. He then opened the hatch and hauled the co-driver out.” The man’s foot was shot off.

German mortar and shellfire from behind Coriano Ridge added to the anti-armour shells scouring the top of the San Andrea spur. Trooper Gordon Carson of Havelock, New Brunswick, jumped clear of his tank after it was hit, only to be struck by a jagged piece of shrapnel. “It entered through my chest and came out my stomach. Immediately thought that was the end of me. I couldn’t breathe and my legs went numb.” Carson lived to see a long life. “B” and “A” Squadron main guns and machine guns answered back in a raging firefight from ridge crest to ridge crest at a range of a thousand metres. Clearly, there would be no going any further north to the Marano River until the enemy’s nest of heavy weapons at Coriano was cleaned out. Since the neighbouring British 5th Corps was not yet up on their left, the obvious solution was for the Hussars to turn left and take out the Coriano strongpoint themselves.

As Howard Keirstead took “B” Squadron over the top, riding hard for Coriano, “A” Squadron poured down cover fire. They made it to the Besanigo stream at the bottom of the narrow valley between Coriano Ridge and the San Andrea spur before German anti-tank fire began to whistle around them. Corporal C.F. Flemming’s tank was hit in the turret and burst into flames. Trooper Joe “Duke” Doucette, an original from Plaster Rock, New Brunswick, was blown to pieces. Flemming and the third man in the turret, Trooper McCallum, were wounded and ablaze. The last two crew, Troopers Charlie Harvey and H.S. Fleming, jumped from their drivers’ hatches up to the burning turret to haul their crewmates out and extinguish their flaming clothes.

German Panzer II turret installed in concrete. Defences like this anchored the coastal zone at the eastern end of Coriano Ridge.

Vern Pearson Collection, PANB

Vicious shooting from every kind of weapon now swept the slopes below Coriano, stabbing at “B” Squadron’s rush. Mercifully, the steep, brush-lined sides of the valley offered cover, but the squadron was pinned down far out in front of the rest of Eighth Army. Keirstead manoeuvred his own tank and Sergeant Keith Fisher’s rear link tank into cover in a depression along the bank of the Besanigo stream, but as they slid into the hole the two tanks collided and bogged. German infantry immediately moved in, shooting shoulder-fired anti-tank Panzerfaust rockets at them from close range. Coaxial machine-gun fire mowed down the attackers. The surviving Germans surrendered to the beleaguered Hussars, who motioned them toward Canadian lines.

As the day wore on, a series of attempts was made to reach “B” Squadron. In the meantime, the isolated Hussars hung on to covered fire positions and took on targets of opportunity. Bob McLeod dismounted numerous times, taking a closer look at targets on foot before returning to his turret and engaging them. One attempt by “A” Squadron to find another way down to Keirstead’s tanks was stopped moments after Lieutenant George Cahoon went over the crest of the San Andrea spur. German anti-tank rounds flew thick enough to “plough the earth” around Cahoon’s tank. His driver shifted into reverse and retreated behind the crest. Sergeant Billy Bell, however, drove headlong into an anti-tank trap. With shells and mortar fire crashing down all along the forward slope of the spur, Bell and his crew had no choice but to abandon their second tank in three days.

Clearly, the German force manning Coriano was no rearguard covering a retreat from the northern Apennine position. It was the newly rebuilt and full-strength 29th Panzer-Grenadier Division, one of several formations rushed forward to stop the Allied breakthrough at the Gothic Line. The Hussars and Westminsters were outnumbered and outgunned. All they could do was wait on the San Andrea spur for reinforcements, under a growing rain of shells, mortar bombs, and rockets. On this day, that terrain feature earned its more common name of “Graveyard Hill.” Fortunately for the 8th Hussars, German tanks and anti-tank guns had far too many targets to fire on so they got off lightly by comparison. 2 British Armoured Brigade, south and west of Coriano, was shattered, losing over two hundred tanks.

“B” Squadron stayed put along the valley floor. A false crest on the front face of Coriano Ridge prevented German anti-tank guns in Coriano from zeroing in and picking them off one by one. Instead, the enemy dumped high-angle mortar and shell fire into the valley in waves. Most of the shells threw blast fragments against Sherman armour plating. During one lull, Sergeant “Tug” Wilson’s co-driver, Trooper Ronald MacVicar from St. George, New Brunswick, slipped out of his hatch to pick some ripe corn growing around them. While exposed outside, the whistle sounded marking the imminent arrival of the next barrage of German shells. MacVicar did not have time to make it back to safety. Blast fragments tore into him. His crewmates pulled him to safety, but his body was too badly shattered to survive. Ron MacVicar died before day’s end.

Late in the afternoon, a Westminster patrol reached part of “B” Squadron and made plans to extricate them at 1800. By then, 5th Division’s artillery would be far enough up with sufficient ammunition to help. In the meantime, Keirstead’s batteries had died and his radio had gone off the net, and notice of the plan apparently did not make it to him. At the appointed hour, Canadian artillery opened fire, smothering Coriano Ridge with shells. “A” Squadron peeled hull-down to the crest of Graveyard Hill, adding smoke shells to the barrage. In the smoke, fire, and gathering darkness, Bob McLeod coordinated with “B” Squadron tanks that were still mobile. He got them to fire up their engines and race back to their comrades, following flares to guide them through the smoke. Six tanks made it back safely. In the hole back on the Besanigo stream, Sergeant Keith Fisher sent his crew off on foot to escape, while he stayed with the radio in his bogged tank. Allied tank stocks, especially in the Italian theatre, were not unlimited, so taking risks to recover salvageable Shermans were worth taking. Fisher assumed that risk for his tank alone; Keirstead and his crew stayed, too. When the covering barrage died down, the six men found themselves alone in the dark, a kilometre from the nearest help. Keirstead eased their spirits by telling them it was only a matter of time before 5th Division attacked and got through to them. They just had to hang on.

Back up behind Graveyard Hill, Bob McLeod, Lloyd Hill, George Cahoon, and Hunter Dunn hatched a plan to head back into the valley on foot to rescue the stranded crewmen. When Dunn briefed Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson about their plan, the CO told them he had “lost enough officers today and he didn’t want to lose any more.” As dismounted night patrolling was an infantry skill, he asked Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark’s Irish Regiment for help. The dark night of September 4 turned into a race to see which army’s patrols would reach the immobilized tanks first.

Graves of Earl Hilchie and Charlie Stevenson behind Graveyard Hill, September 1944.

8th Hussars Regimental Museum

German panzer-grenadiers won the race. They crawled through the blackness and got close enough to fire Panzerfaust rockets. Two crunched into the side of the rear link tank manned alone by Keith Fisher. Neither pierced the armour, but Fisher decided the time had come to get out. “My chances, I figured were not good so I tore off my stripes, hid my pay book, took off my boots and decided to go.” He slipped out the escape hatch beneath the Sherman only to hear enemy troops talking nearby. A third rocket hit Keirstead’s Sherman, punching through and flinging metal shards around inside and starting a fire. Keirstead and his four crewmen bailed out. German machine guns lit up the darkness. Trooper Earl Hilchie from Noel Shore, Nova Scotia, fell dead. Trooper Charlie Stevens, a low-number Hussar (G/191), was hit in several places and paralyzed below the waist. Keirstead was hit, too, with seven bullets in his leg and two more in his arm. Lance-Corporal John Wentworth crawled to his squadron leader’s aid but machine guns barked again, hitting him in his left calf and right thigh, cutting open his femoral artery. Acting Sergeant Charlie Stevenson, who commanded Keirstead’s tank while the major led the squadron, was the only one left unwounded. The German patrol, apparently content they had finished their work, seemed to have left. Stevenson volunteered to make a break for it to get help. Keirstead agreed and told him to try. Stevenson vanished into the darkness and clambered aboard the still-intact rear link tank to try to hail R.H.Q. on the radio. Just as he made it to the hatch, German machine-gun bullets lashed into one of Chipman, New Brunswick’s, finest sons. That night, an Irish Regiment of Canada patrol got within seventy-five metres of the wounded men, but on hearing nothing but German voices after the brief night battle for the stricken tanks, they assumed the crews were dead.

When dawn broke, Keirstead and Wentworth saw Stevenson’s lifeless body hanging from the turret. Charlie Stevens was in terrible shape, lapsing in and out of consciousness. Wentworth was fading, too, from loss of blood from the wound in his thigh. Keirstead decided to crawl for help. On the way, he was hit by mortar fire and ended up in an Italian farm house in the middle of no-man’s-land under the care of a civilian family and a band of German deserters. They eventually carried him across the front and his broken body was taken to a hospital, but the war was over for the old Hussar who had first joined the regiment in the 1930s.

On the third day, Keith Fisher found Wentworth and Stevens. Fisher treated Wentworth’s thigh with anti-bacterial sulpha drugs, saving the leg. Stevens was in much worse shape. Fisher cut away his filthy, blood-soaked uniform to clean and dress the bullet holes around his spine, before putting his own coveralls on the wounded man. Fisher kept them both alive and fed. He also buried Hilchie’s body; there was too much steady shell fire in the valley to reach Stevenson’s body. The three lonely Hussars survived for six days trapped along the Besanigo stream. Finally, on the night of September 9, a Perth Regiment patrol found them and brought them home. Sergeant Keith Fisher won the Military Medal for standing by the two badly wounded men. Thanks to him, John Wentworth made it to hospital and lived to tell the tale. It was too late for Charlie Stevens. He survived all that time with four bullets in his back only to die on the way to hospital. But it was not for lack of trying. Keith Fisher’s medal citation reads: “He was only slightly wounded and could have at any time returned to his Regiment. That he did not do so is an inspiring example of unflagging courage and devotion.” Keith Fisher was also promoted to warrant officer II class and appointed squadron sergeant-major.

Their incredible story of survival in no-man’s-land between Coriano Ridge and Graveyard Hill revealed the falsity of earlier indications of an enemy withdrawal from Italy. Instead, a tidal wave of German reinforcements arrived to stop the Allied breakout. Along Coriano Ridge, six British, Indian, and Canadian divisions faced eight German divisions. The next phase of the operation would be a massed battle of destruction against a now equal-sized enemy force.

The Allied offensive necessarily paused after the initial surprise attack. Reserve formations were brought up, supply lines extended, tired units rested, and replacements distributed to fill holes in the ranks. Battle-damaged and hard-driven tanks and vehicles were patched up, while long service corps convoys hauled ammunition and fuel to new forward dumps. Air and ground patrols scoured the front to gather intelligence. Eighth Army was readying itself for what must be the toughest part of this battle.

It was to be a new kind of action for the 8th Hussars. In the Liri Valley, and even in the main Gothic Line, they had faced wavering enemy forces already broken by long action in comparatively fluid battles of movement. Now, the opponent was fresh, strong, prepared, well dug in, concealed, and held excellent defensive ground overlooking the Canadian front. The enemy force on Coriano Ridge was the strongest the 8th Hussars had ever faced in terms of both men and weapons. The mission now was not to break through the enemy line and seize a glorious prize, but to wade into a powerful enemy force and destroy it.

The regiment spent four days sheltering behind Monte Gallera on Misano Ridge as the divisional counterattack reserve. There, they made ready for the coming reckoning. But no place was entirely safe. The Germans packed more artillery and ammunition behind their Coriano battle line than any other position in the Italian theatre. They transferred medium bombers to strike Allied lines at night. The Canadians on the receiving end faced their heaviest enemy shelling and bombing of the entire war. The Hussars caught sleep whenever they could, either in deep trenches or inside turrets. Life was made miserable by heavy rains that saturated the earth, filled trenches, making sleep impossible, turned dusty roads into muck, and prolonged the build-up and wait for the coming battle. Still the enemy shells fell. One night, Hunter Dunn lay inside his trench during a German barrage when a shell burrowed into the earth right beside him. It should have exploded and buried him alive, but the fuse failed. Dunn “silently gave a prayer for some slave worker in a German ammunition plant who probably sabotaged that shell.”

Under incessant shelling, the regiment again reorganized squadrons after their losses of September 4. “A” Squadron received its second new leader in a week after Lloyd Hill also succumbed to jaundice. Gordon Bruce was promoted acting major to take his place. He was traded for George Cahoon, who was promoted to acting captain and sent to fill Bruce’s position as “C” Squadron rear link. Acting Major “Tim” Ellis moved up from H.Q. Squadron to take over “B” Squadron. Bob McLeod became second-in-command, and Tom Robertson was promoted to acting captain to become “B” Squadron’s rear link.

In the darkness of September 8, the squadrons returned to the reverse slope behind Graveyard Hill and tied in with their 11 Canadian Infantry Brigade brothers. Each squadron was assigned to marry up with its usual partners. Gordon Bruce settled “A” Squadron in with Bill Reid’s Perth Regiment on the southern most part of Graveyard Hill, opposite the left end of the enemy-held ridge leading out of Coriano. The next night they rejoiced and grieved when a Perth patrol brought in Keith Fisher, Wentworth, and Stevens. In the centre, directly opposite the town, Cliff McEwen joined “C” Squadron with Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark’s Irish. Further north, in the lee of Graveyard Hill, Major “Tim” Ellis tied “B” Squadron in with Lieutenant-Colonel Boyd Somerville’s Cape Breton Highlanders. The force was joined by a troop of armoured engineers crewing Sherman dozer tanks and 5th Division’s engineer field squadrons to clear mines and force crossings of the Besanigo stream. They were backed by the full weight of Canadian Corps artillery.

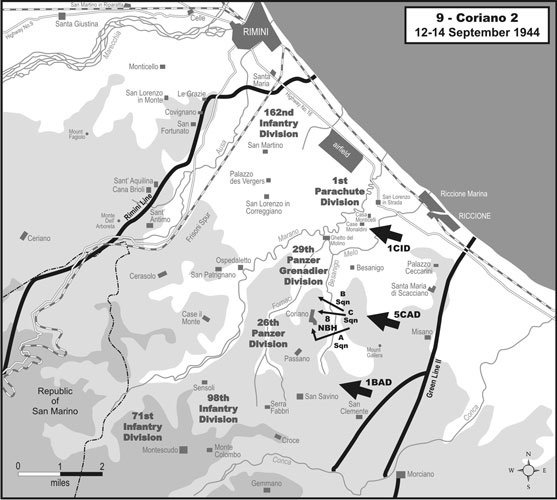

Second Battle of Coriano.

Mike Bechthold

In the last hours of September 12, the wait ended and the whole front line from Florence to the Adriatic erupted with fire and death as the Allied armies stormed the corridors of hell. At 0100 on September 13, the full weight of Canada’s artillery, reinforced by a dozen British, Indian, New Zealand, and Greek artillery regiments, smothered the Germans on Coriano Ridge with field gunfire and hurled carefully hoarded stocks of medium and heavy shells at known German artillery. But the sheer number of German guns assembled, shielded in the ravines and reverse slopes behind the ridge, made suppressing all enemy artillery impossible. A thunderous artillery duel played out over the heads of the infantry and tankers poised for the attack. German counterbattery fire was thick, directed by intelligence gathered from mountain observation posts in the days before, and scored direct hits on Allied gun positions densely packed behind Graveyard Hill.

Brigadier Ian Johnston’s 8th Hussar-11 Infantry Brigade team faced an equal-sized and well-armed force from the German 29th Division’s 15 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment, parts of the 71 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment, and the left edge of 1st Parachute Division, all covered by a powerful anti-tank gun line and the 129th Panzer Battalion, over and above the mortars and artillery pieces shielded behind Coriano Ridge. The forward slope of the ridge was covered with mines and protected by the natural anti-tank ditch of the Besanigo stream.

Coriano Ridge was well suited to the defence. The slope facing the Canadians was gradual, creating a thousand-metre-wide kill zone. Behind the town, the slope dropped sharply, providing excellent cover for German mortar crews. The steep back slope was controlled by a tiny plateau behind the main crest at Point 102. The location had just enough elevation to offer a commanding view of the valleys in front of and behind Coriano. The defensive value of the location had been evident to the Renaissance dukes who fortified it with one of the numerous small castles scattered around the affluent provinces of Rimini and Pesaro-Urbino. In front of the old castle stood the town’s church, directly on top of the highest part of the main crest of the ridge. The strongest part of the Coriano Ridge defence, in fact, was the thick-walled stone and masonry buildings in the town, and the Germans had turned both the church and il Castello into the main bastion.

Crossing no-man’s-land between Graveyard Hill and the Coriano Ridge fortress was a challenge of Great War proportions. Doing so in daylight was impossible, especially as the Shermans would have to move across prepared anti-tank kill zones. The solution was to attack with infantry first under cover of a barrage and darkness. Brigadier Johnston planned to seize the ridge on both sides of Coriano with a night infiltration by the Perth Regiment on the left and the Cape Bretoners on the right. Once the infantry were across, the engineers would gap the minefields, opening up two crossings over the Besanigo. Then Gordon Bruce and “A” Squadron would close up with the Perths and “Tim” Ellis would bring “B” Squadron to the Capers. McEwen’s “C” Squadron and Bobby Clark’s Toronto Irish were to remain on Graveyard Hill in reserve. When the first two teams had firm control of the ridge, “C” Squadron and the Irish would take on the Coriano strongpoint itself. They also had orders to lend a hand with gunfire support for the night attacks.

As soon as the Canadian artillery barrage opened up, Lieutenant Ron Lisson’s troop from “C” Squadron drove up onto the heights behind Graveyard Hill, just below Monte Gallera. The spot was three thousand metres from Coriano and well out of range of the enemy’s powerful anti-tank gun line on the ridge. But the German guns were well within range of the high-explosive shells of the Shermans’ 75s. To avoid drawing enemy artillery fire the day before, Ron Lisson had staked out each tank’s firing position and a gun-zeroing line, just as they had done back at Ortona. The troop’s four tanks carefully jockeyed into position in darkness broken only by the stabbing flashes of the massive artillery duel playing out before their eyes. Lit cigarettes were laid on top of the zeroing stakes so gunners could find them in their sights. At 0150 they opened fire. Each Sherman fired one hundred rounds at the front face of Coriano, adding weight to the artillery shot crashing into the buildings still standing in the town. Suffering the misfortune of being the front line for a week, Coriano was all but destroyed. The fire also kept the heads of German anti-tank and machine gunners down and their tanks tucked behind the crest while the Canadian engineers worked on the crossing sites. Once they were finished, Lisson moved his troop back to shelter to refill ammunition bins with the proper mix of high-explosive, smoke, and armour-piercing rounds. They then rejoined “C” Squadron and made ready to go into the town they had just flattened.

On the Canadian left, south of Coriano, the Perths ran down Graveyard Hill, splashed across the creek, and rushed up the ridge. Artillery fire kept most of the Germans pinned in the bottom of their trenches and bunkers as the Perths traversed the small valley, but, as usual, destroyed few of the well-dug-in and fortified positions outright. The Perths arrived on their designated objective in the midst of German trenches, pillboxes, and fortified buildings around a knob on the ridge five hundred metres south of Coriano identified as Point 124. With bayonets, grenades, and Tommy guns, they took ownership of the point. All four companies formed a box, with two companies on the crest and two on the reverse slope, and made ready to defend in all directions. Throughout the early morning, German defenders emerged, shaken by the bombardment. Some surrendered, but others fought it out. Seven Panzer IV tanks lurking in the darkness behind houses around the south end of town were held at bay by Perth PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-tank) teams for the time being, but they needed the Hussars to arrive by dawn, before the German tanks could form up with infantry to counterattack.

At the north end of town, the Cape Breton Highlanders had a tougher time. The lead companies crossed the Besanigo at 0130, just as a German mortar and artillery back-barrage plastered the valley floor. Most Highlanders found cover from the bursting shells only to be met with a wall of German machine-gun fire on the east bank. The reserve companies joined in the fire fight, and the whole of the regiment fought its way up the gentle slope to the friendly side of the crest in the dark using platoon fire and movement drills. It took two hours to battle up the five-hundred-metre-long slope, but by 0400 Somerville’s Capers had gained the crest and started digging in.

Fifth Division’s engineers moved down to the Besanigo stream right behind the infantry and ahead of three Sherman dozers. Canadian sappers went to work clearing mines booby-trapped with anti-lifting devices so the dozers could get on with digging into the banks to make temporary fords for the 8th Hussars. German artillery and Nebelwerfer multiple rocket launchers doused every potential crossing point with pre-registered and deadly accurate fire, making the engineers’ work dangerous and slow. Two Sherman dozers were smashed up by bursting shells, so unarmoured D-7 dozers from 5th Division came forward to finish the job, however dangerously exposed they were. “Tim” Ellis watched “one little engineer go down into the valley with nothing on his head at all. Just sitting there on his bulldozer. I said to myself ‘goodbye young man’.”

Engineer casualties mounted and clocks ticked toward dawn. At 0530, just before first light, the southern crossing was ready. Time was of the essence for Gordon Bruce, Hunter Dunn, and “A” Squadron. Each squadron tasked an officer to stand by at the crossing point ready to signal that it was open and to guide the tanks down. Through the early morning half-light, the Perths sent guides to bring the Shermans up to their rifle company positions. Moving tanks through prepared defences in the gloom was no easy task. To make matters worse, the Hussars lost radio contact with the Perths just as the tanks moved forward. The infantry were still fighting for control of Point 124, and in the confusion “A” Squadron’s leading Shermans fired on “C” Company’s command post until Major Harvey White managed to identify the position as friendly. A few metres away in the squadron rear link tank, Hunter Dunn watched four Germans bolt for a stone house. The tank’s coaxial Browning machine gun began chasing them ten metres behind. Dunn recalls that, “when the enemy was about five yards from the house, a Perth soldier came out of the house with a Thompson submachine gun and motioned the enemy into the house.” Dunn ordered his gunner to cease fire before he hit the Perths. The incident caused frayed nerves but no casualties.

Casualties, however, occurred elsewhere. An explosion underneath an “A” Squadron Sherman was more powerful than that of a normal Teller mine, as though several mines had been wired together. The blast blew off the tank’s suspension and wounded two crewmen. The dawn was full of surprises. A German anti-tank gun cracked off a shot at the lead troop, but missed. The troop behind, covering their move forward, spotted the flash and unleashed a salvo of 75mm shells. The unit after-action report recorded that the enemy gun was “knocked out.” After that, Major Bruce sited each troop carefully to protect the Perths’ hold on Point 124 and to ready the newly conquered fortress against the expected counterattack. Perth section and platoon commanders crawled back to “A” Squadron Shermans to point out targets in nearby houses and pillboxes. The squadron got to work. Particularly troublesome were a half-dozen Panzer IVs lurking at the south end of Coriano. Never one to be far from the centre of action, Squadron Sergeant-Major Ralph Wallace manoeuvred his H.Q. Squadron Sherman to get a clear shot at a Panzer that was sniping from behind the town’s hospital. He knocked it out, and other Hussar 75mm guns helped confirm Canadian ownership of Point 124.

Coriano rebuilt, as it appeared in 2010.

Courtesy of Eric McGeer

Around the same time, a troop of “C” Squadron tanks and another of M-10 tank destroyers popped up over Graveyard Hill immediately opposite Coriano. A company of the Irish covering the engineers at the crossing site below could see targets as the sun came up over the Adriatic Sea at their backs, and directed the guns of the Shermans and M-10s right onto the enemy positions by radio. The 11 Infantry Brigade 8th Hussar all-arms team was working with ruthless efficiency.

Although covering fire helped the engineers at the northern crossing, as daylight gathered the route was still not open for tanks. The crossing site lay near the elbow of the enemy line in a crossfire and only a few hundred metres behind the raging Cape Breton fight for the north end of the ridge. German artillery shells, mortar bombs, and rockets landed more densely there than at any other point on the Canadian front, spraying white-hot fragments in every direction. Major “Tim” Ellis chomped at the bit in frustration, waiting to get his “B” Squadron tanks onto the ridge to help the Cape Bretoners. Five hours had now passed since the battle had started — plenty of time for the Germans to move reinforcements in behind Coriano to counterattack in daylight — indeed, Eighth Army ground and air observation reports suggested that 29th Panzer-Grenadier Division was trying to do just that. It was not clear how much longer “B” Squadron would have to wait.

At 0600 Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson ordered Cliff McEwen to take “C” Squadron across the southern fording site and tuck in under the false crest five hundred metres below the smoking but still deadly Coriano fortress. As powerful as the German-held ridge was, the false crest was its Achilles’ heel. Today’s travellers to the area driving on the road from San Andrea across the tiny bridge over the steep-banked Besanigo have a grandstand view of Coriano Ridge until they get part-way up the road into town. Then, like the mythical Brigadoon, Coriano vanishes behind the false crest, which stands between fifty and fifty-five metres in elevation. It was in this enclave of protected dead ground underneath the false crest that Robinson wanted “C” Squadron to assemble. If a German force gathered with tanks to counterattack the Capers, McEwen was to fight his way north, across the front of the Coriano fortress at all costs. The 8th Hussars would not fail in their mission to support the infantry this day or any other. The risk of exposing “C” Squadron’s left flank to short-range fire was tremendous, but better than the prospect of German tanks overrunning the Cape Breton Highlanders. McEwen moved his tanks into the valley, through cleared lanes in the minefields, and into position in front of the town, all amid a continuous storm of mortar and artillery fire. At 0730 they were ready to go, but thankfully never got the call. A half-hour later, at 0800, the north crossing opened. “Tim” Ellis and “B” Squadron took off like a shot, riding hard down Graveyard Hill to the mine-cleared crossing and up to the northern extension of the false crest beneath the hamlet of Villa Salvoni, five hundred metres north of where “C” Squadron lay sheltered.

“B” Squadron found their old friends from Cape Breton dug in between the main ridge and the false crest, short of Villa Salvoni. German shell and mortar fire had blown large holes in the Cape Breton ranks. One company had lost all of its officers and was held together by its company sergeant-major. “Tim” Ellis dismounted from his H.Q. tank around the same time that Lieutenant-Colonel Somerville moved his battalion command post up to the false crest. The Capers controlled the near side of Coriano Ridge from the false crest to just short of the main crest. The Germans, however, had turned Villa Salvoni, a cluster of thick-walled stone houses on the main ridge, into strongpoints defended by machine guns and anti-tank guns. Lieutenant Bill Spencer was the solution to that problem. Major Bob Ross said he was “a ball of fire and had his troop into and out of scrapes as fast as the law allowed.” Spencer used the false crest to shield his tank as he lined it up on one particular German-held house sporting multiple machine guns. Once in position, he toggled his radio switch to the crew intercom net and ordered “driver advance.” Up popped Spencer’s turret, the main gun already loaded with a high-explosive shell with a one-twentieth-of-a-second-delay fuse, purpose built for blowing bunkers. The gun roared, and scarcely a second later the shell punched through the front wall of the house. Rather than bursting on contact, the delay fuse detonated inside. The explosion blew off the roof and flung the doors and windows out of the house. Spencer then dismounted with a Thompson to clear the rubble himself. “He had almost reached the casa when a very large and very much alive Jerry closely followed by a couple of his pals, all equipped with the latest pattern of Jerry-issue weapons, came tearing over what had been the welcome home mat.” Spencer loosed off a burst of .45-calibre fire, shooting off the foot of his lead assailant and stopping the rest.

By 0830 all three Hussar squadrons and their infantry partners had received orders to dig in and stand to. Allied observation planes spotted the 129th Panzer Battalion moving up from the inland heights toward Coriano, along with infantry in trucks, apparently assembling to put in a powerful counterattack. Canadian tanks, anti-tank guns, and infantry found protected fire positions and made ready. But they never got the chance to fire. An air spotter plane called in heavy concentrations of long-range medium and heavy artillery fire onto the Germans as they formed up. After that, Allied fighter bombers circling overhead pounced, strafing the convoys. 29 Panzer-Grenadier Division’s counterattack to retake Coriano Ridge was destroyed before it ever started. The 129th Panzer Battalion lost nineteen tanks in the firestorm.

Nevertheless, the survivors of the 15 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment, backed by a company of a panzer battalion, fought on for possession of the crest and still held the Coriano fortress itself. In the mid-morning, “Tim” Ellis ordered “B” Squadron to advance in front of the infantry to the top of the ridge north of town. He walked on foot with Somerville’s command post team, coordinating his four troops with the Cape Breton companies. Working together, they inched slowly and steadily up the ridge, blasting every house they encountered. Once each was opened like a sardine can, Highlanders swept into the remains with grenades and bayonets to clean out the panzer-grenadiers.

Knocked-out Panzer IV in the rubble of Coriano.

LAC e-008303220

It fell to the Irish Regiment of Canada and “C” Squadron to take the fortified town, with its commanding view in all directions, from the enemy. Brigadier Ian Johnston was not going to attack 29th Panzer-Grenadier’s strongest positions frontally if he could avoid it. Instead, he directed Lieutenant-Colonel Bobby Clark to take the Irish through the Cape Breton foothold and into town from the north end. The Irish companies filtered into the valley in the Cape Breton zone one at a time and took position south of the Highlanders and “B” Squadron. Not long after first light, the lead Irish company crept into the smashed remains of Coriano. Initially, it seemed abandoned, and one company of infantry appeared to be enough to secure the main part of town. Just before 0900 Clark’s “C” Company reported they were through Coriano and overlooking the valley beyond it. Word came back to the Hussars for “C” Squadron to stand by for Phase II, the attack on the church atop Point 102 in the centre of town and the medieval castello on the plateau behind it. Two troops from McEwen’s squadron moved up to the north end of town behind the Irish while the rest covered them from the false crest.

It seemed as though 5th Division’s battle for Coriano Ridge might be over. Late in the morning, however, all hell broke loose inside Coriano. The 15 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment had taken casualties but was not broken. They still held the town in strength and, manning carefully prepared positions, were not inclined to give it up. They had gone to great efforts to lay mines and explosive traps, covered by snipers, tanks, and numerous machine-gun posts. At 1025 the Toronto Irish reported serious trouble: their lead company was ambushed, cut off, and surrounded. The Germans fought them from half-demolished houses under covering fire from a low hill feature connected to the line of the ridge. The church and castle that crowned it stood fifty feet higher than the north end of town and dominated the skyline. They also controlled the valley beyond Coriano Ridge and offered a covered withdrawal route when such time came. But that time was not September 13. Bobby Clark put one of his Irish companies on the enemy side of the ridge north of town, where they could put down rifle, Bren gun, and 2-inch mortar fire on the castello. Major Frank Southby took another rifle company into town to reach the trapped Irish company. Robinson ordered “C” Squadron to follow them, but it would take time for them to get there.

The fight for what was left of Coriano suddenly turned to a vicious ambush. Enemy snipers, machine-gun nests, and tanks were hidden in rubble heaps and behind walls. The tanks of “B” Squadron’s 3 Troop, on the south end of Villa Salvoni, were the closest to the Irish at that moment. The turret crew of Troop Sergeant “Tug” Wilson’s tank, positioned to cover the south, toward Coriano, saw German muzzle flashes and began to blaze away to cover Major Southby’s company, which was making its way south to rescue the trapped Irish company. The driver, Trooper Roy Robertson, watched them go in: “I recognized through my periscope sight Major Southby and the Company Sergeant Major, carrying a No. 18 [radio] set,” when Southby was “suddenly hit by sniper fire and went down.” He half-crawled, half-fell into a German slit trench. The company sergeant-major rushed to his company commander’s aid, only to have his stomach shot open.

3 Troop was led by Lieutenant Lloyd Brown, a replacement officer fighting his first battle. Major Bob Ross came over the radio and asked Brown and Sergeant Wilson if they could rescue Major Southby. “Tug” Wilson put it to his driver over the intercom. “It’s up to you, Trooper Robertson. If you think we can do this, we’ll close up and proceed.” Robertson agreed to try. Brown swung his turret at the source of the enemy fire and opened up. Robertson drove out into the exposed ground toward the wounded infantrymen. Anti-tank shells whistled past them. Robertson remembers being “so intent on the job at hand that the fear didn’t really register.” Wilson guided his skilful driver right over the trench. Robertson opened the escape hatch and saw Southby lying at the bottom of the trench. “He was in tremendous pain and bleeding heavily. Time was of the essence. I fastened a web belt around him, placing it under his arms, and then hoisted him above me up onto the floor of the tank.” Once inside, “Tug” Wilson gave Southby a shot of morphine and put shell dressings on his bleeding wounds. A second 3 Troop Sherman tank drove over top and picked up the company sergeant-major. Tragically, despite their heroism, Southby died of his wounds.

The fight for Coriano did not stop. The size of the major market town swallowed the tiny force trying to clear it. Two rifle companies and two tank troops might have been enough to chase out an enemy withdrawing from a lost cause, but the 15 Panzer-Grenadiers fought viciously to hold Coriano. McEwen’s two tank troops were pushing their way south into the central square, or piazza, making for the trapped Canadian Irish, when they too were ambushed. The last tank in the line was commanded from an open hatch by Sergeant Don Watkins, an original Hussar from St. Stephen, New Brunswick. In the closed-in streets, he was taking a huge risk, but he felt it was worth it because of the difficulty of staying aware of the tank’s surroundings at close range with hatches locked down. The decision cost him his life when a sniper’s bullet found him. His driver, Trooper Emmett Hart, geared into reverse and hit the throttle, but not before a heavy Panther tank opened fire from across the piazza and stopped them cold. Hart was wounded, and his co-driver, Trooper W.E. Fitzgerald, pulled him out of the hatch and dragged him to an empty house, where they remained hidden for the rest of the day. The wrecked tank, though, blocked the escape route leading north out of the square.

Meanwhile, German infantry emerged from nearby houses and let loose with a salvo of Panzerfaust rockets at the seven remaining Shermans. The tanks returned fire with main guns and machine guns, turning Coriano’s town square into a close-quarter battlefield and shaking the foundations of the church, which stood above the square on Point 102. A statue of the Madonna swayed back and forth, threatening to fall, but miraculously stayed erect.

The Germans were held at bay for now, but without friendly infantry to protect them from rockets and anti-tank grenades thrown at close range, the Hussars’ tanks would be picked off one by one. McEwen’s crews also could not see to get a clear shot at the cleverly concealed enemy Panther. George Robinson followed the action from the R.H.Q. tank parked at 11 Brigade’s command post. He knew all too well from his time at Ortona how tanks in an urban space needed infantry close to them. He radioed McEwen to fight his two troops out of town before they were hunted out of existence. McEwen, running to the square on foot to get that job done, ordered a second tank to hitch up to Watkins’s hulk and pull it out of the way so the rest could exit. As if to emphasize how dangerously exposed they were, a Panzerfaust hit and stopped the second tank. The crew bailed out with bullets licking their heels. Sergeant Jack Constable (G/297), from Moncton, raced out into the smoke and fire with his co-driver, Trooper Price, and got a cable on Watkins’s tank. The tracks and road wheels were intact and the brakes still worked, so Price climbed into the driver’s hatch to steer the stalled Sherman while Constable’s own tank towed it clear. The crew from the second knocked-out Sherman jumped aboard and they pulled out of the piazza. The remnants of the squadron withdrew to the northeast edge of town and spent the rest of the daylight hours shooting at targets to support the deliberate house-to-house clearing operation. It was a terribly frustrating process to watch.

The fight around Coriano raged all day. German panzer-grenadiers and tanks fought for every building still standing and for every heap of rubble. From their key point of elevation around the church and castle, the Germans could see enough of the valley in front of the town to call down pre-registered artillery shoots there. Among their targets was a convoy from 4th British Division, coming forward to relieve the Canadians and carry the attack beyond Coriano to enemy positions on Ripabianca Ridge. By the end of the day, though, the Germans had been evicted with heavy loss from most, but not all, of Gemmano-Coriano Ridge. In the Canadian Corps zone, the 15 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment, which had arrived fresh at the front only days before, suffered over fifty percent casualties on the first day of battle. But the survivors were still cohesive and holding prepared positions in Coriano’s castle and behind it on Ripabianca Ridge.

As the sun went down over the smoking ruins of the town, all three squadrons took up positions backstopping the three infantry battalions on the crest of Coriano Ridge. Major Jack Boyer’s “A” echelon filled up Recce Troop’s Honeys with ammunition, fuel cans, and rations, and drove onto the battlefield after dark to replenish each squadron in turn. There was much work to do to rearm those close to the Germans. Enemy mortar and artillery fire continued to hammer the Hussars, as well as the Perth, Toronto Irish, and Cape Breton infantry dug in around the crest. Bursting shells and the threat of counterattack made for a sleepless night for all but two Hussars. Trooper Ralph Chapman from Mount Middleton, New Brunswick, and Trooper Wilfred Adams, also a New Brunswicker, died of their wounds before midnight. In retrospect, given German strength and firepower on Coriano Ridge when the attack started, it is remarkable that losses were not much higher.

The fighting, however, was not yet quite over. During the night, the Germans positioned fresh troops on Ripabianca Ridge — their new main battle line in front of the Marano River. They also still held the castello in Coriano as an outer bastion to this new fortified wall. The 8th Hussars thus had two interdependent jobs to perform before they could be pulled off the line for a rest. First, they had to blast the panzer-grenadiers out of the castello and cover the Irish Regiment as it moved in. They also had to cover 4th British Division as it surged over Coriano Ridge and onto the next ridges, handing over the baton in a fiery relay.

When the sun rose on September 14, German shell and mortar fire again swept across Coriano Ridge. The enemy knew 4th British Division was coming and was trying to stop it. The Canadians from 1st Division, fighting hard for the lower ground to the right, desperately needed the British on top of Ripabianca Ridge, which overlooked their shoulder. So “Tim” Ellis took “B” Squadron back over the top of Coriano Ridge where they could see to fire. British infantry stormed down the valley beyond Coriano and up to Ripabianca Ridge, accompanied by heavy Churchill tanks from 25 British Tank Brigade. Ellis had “B” Squadron Shermans fire smoke rounds at the next ridge to blind the Germans to the British attack, which brought a firestorm back onto the Hussars. Ellis recalls how “our 75mm smoke rounds left a bright tracer path. It led German gunners straight back to us.” German super-heavy 170mm gun batteries zeroed in on “B” Squadron, their massive shells crashing into Coriano Ridge all around the tankers. “I thought the war was over for us,” Ellis says. Corporal Willis Holt was killed in the barrage, but miraculously only one other man was wounded. “Tim” Ellis pulled the rest of the squadron just behind the crest. Then a voice crackled on the Squadron H.Q. radio telling him to “come forward” again to the crest. “I knew it wasn’t George Robinson. He would have said ‘go’ forward.” It was not uncommon for electronic warfare units on both sides to listen in on the opponent’s radio traffic, but this kind of deception was too much for Ellis. In the thickest New Brunswick accent he could manage, he yelled into the radio handset, “Get the hell off the air, you German bastard!”

By 0800 the British were on Ripabianca Ridge and fighting off German counterattacks. “A” and “B” Squadrons took on targets of opportunity whenever they could to help. Meanwhile, “C” Squadron went back into Coriano with the Irish. Again, the Germans at first seemed to have abandoned the town, so Major Bill Armstrong of the Toronto Irish and Cliff McEwen walked into the main part of town to check it out, following behind a three-man recce patrol. Suddenly, a huge German panzer-grenadier loomed in a doorway beside the two majors. Armstrong was carrying a rifle and McEwen a Thompson. The infantry major spotted the German first and said “Lend me your Tommy gun.” McEwen passed his weapon to Armstrong, who then calmly fired a close-range burst, eliminating the threat.

The town, in fact, was still alive with snipers and isolated pockets of resistence. Bobby Clark’s Irish controlled the north half of town, but survivors of 15 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment still held what remained of the church and castle perched on the hill. For the rest of the morning, the Irish and “C” Squadron carefully worked through the rubble, cleaning out every building. No one was taking risks. The infantrymen reported the locations of snipers back to the tanks, which promptly blasted them out of windows and doors or straight through solid walls with 75mm shells. The whole process went on until 1400. By then, the Irish and “C” Squadron had closed the ring around the enemy besieged in the centuries-old castello. After the artillery had softened it up, “C” Squadron jockeyed into fire positions behind Coriano Ridge, directly overlooking the northern walls of the medieval fortress. They let fly with all weapons as two Irish companies stormed the shattered ramparts. This time, the surviving Germans from the elite 29th Panzer-Grenadier Division gave up. The battle of Coriano was finally over.

In the broken remains of the main square, the Hussars found an abandoned Panzer IV that had been part of the force that ambushed them the previous day. Demolition charges were laid to blow it up, rendering it useless for an enemy who might recapture it. The fuse went out, however, and those on the scene had second thoughts, but no Germans were ever to get back into Coriano to use the tank. By that afternoon, 4th British and 1st Canadian Divisions had carried the fight well beyond the town. Instead, the 8th Hussars took the Panzer as a massive trophy.

Even after the Germans had left the battlefield, they were still dangerous. Their engineers had developed the deadly practice of laying I.E.D.s long before wars of the twenty-first century gave them notoriety. In “A” Squadron’s area south of town, Trooper Hills asked Captain Hunter Dunn if he could go scrounging for German cooking pots; his crew’s pot set had been blown off the stowage racks on their turret during the battle. Dunn agreed, but went with him, searching through the wreckage of blown-out pillboxes and trenches left from the battle for Point 124 the day before. After a brief search, Dunn told Hills it was time to get back to the tanks. Hills asked if he could keep looking. Dunn gave him the OK and returned to the rear link tank. As he reached it, he heard an explosion. A trooper ran to Dunn’s tank to report that Hills had hit a mine or booby-trap and was wounded. “I told him to run back and tell Hills not to move.” Apparently, Hills had given up his search after Dunn left, but then spotted a container on a dead German only fifty metres from his tank. It looked like it might do as the crew’s new pot. His crewmates warned him there were mines and booby-traps all around, but he went on anyway, eager to provide for his mates. Dunn got on the radio in his tank to call for the medics. In the meantime, he ordered his crew to fire up their engines and get over to the blast site, calculating that anti-personnel mines or explosive traps could not stop his Sherman. “I planned to drive up to Hills and have two members of my crew lift him onto the tank. I was in the process of turning the tank around when there was another explosion.” The same Hussar who had first alerted Dunn ran back and told him there was “nothing anyone could do.” Hills had tried to move, triggering a secondary device, and died at the scene. Trooper William John Hills was the same brazen Hussar who had rescued the trapped driver from a stricken Sherman ten days earlier during the first attempt to reach Coriano. He knew no fear.

Hunter Dunn carried the burden of Hills’s death for decades after the war. “I still wish I had told him to return with me.” Dunn visits the twenty-five-year-old’s grave whenever he returns to the Coriano Ridge War Cemetery. He also regularly visits the twenty-eight other 8th Hussars left behind in the three cemeteries between the Gothic Line and Coriano Ridge. In 1944, the path between those three burial grounds marked an arduous sixteen-day journey through the fire and smoke of battle. The 8th Hussars now deserved a well-earned rest.