THE MALMÉDY TRIAL

1945-46

For Sepp Dietrich there now began a period of ten and a half years of captivity, initially as a prisoner of war and then as a war criminal. After his capture he was held in Kufstein for a few days, as was Ursula, although separately. She did however, have at least one opportunity to visit her husband. Yet, although captured on 9 May, it was not until 13 May that HQ Seventh Army released the news that they held Dietrich. At this stage the press release merely spoke of the Russians holding him responsible for the Kharkov atrocities.1 On 15 May he was transferred to Augsburg, where senior German officers and political figures captured by the Americans were being concentrated. It was now that questions were first asked of him about the Malmédy affair. In the meantime, his father-in-law had also been arrested, leaving his sons temporarily in the care of just their nurse since Ursula had also been brought to Augsburg to help her husband write an account of the war as he saw it. He was taken on the pretext that he had been a colonel in the First World War. The family, however, remain convinced that it was because of his relationship with Sepp.2

Dietrich’s first interrogation was on 1 June and seems to have been general in nature. His interrogators, Captains Hans Wallenberg and Ernst Langendorf, wrote in their report:3

‘Sepp Dietrich is a talkative man who takes great pleasure in discussing military and technical matters and constantly refers to his thirty-five years of soldiering in order to evade all political issues. He expresses himself in an original and blunt manner, a form of speech which betrays his working-class origin, and which is not without wit and humour. His criticism leaves little merit with either military or political leaders of the Third Reich. In spite of his sketchy educational background, one cannot deny that he possesses, to a certain extent, sound instinct and “horse sense”.’

While he stated that he had been ‘completely cured of this [National Socialist] system in which swindle and graft was [sic] rampant’, he also said, somewhat contradictorily, ‘I have been a member of the Party since 1928 and I intend to stand by it today.’ He then went on:

‘I could have put a slug through my brains if I wanted to but I have a responsibility for which I must make a stand. I want to speak for the men I once led. I never signed any order providing for the massacre of the Jews or the burning down of churches, nor have I ordered the pillaging of occupied places. I therefore want to clarify things and stand up for my men. ’

He now went on to give his views on some of the prominent leaders of the Third Reich. Hitler ‘knew even less than the rest. He allowed himself to be taken for a sucker by everyone’. Goering ‘was a lazy bastard; a clown’. Heydrich was ‘a great pig’, but Kaltenbrunner, chief of the RSHA and later hanged after the Nuremberg trials, ‘was a decent fellow who had to do a lot of things which he did not like to do. He had many a heated argument with Himmler.’ Dietrich’s views on Himmler have already been given (see Page 51), and it would seem, at least according to his family, that Himmler was the one man that he really hated.4 Hence, it is understandable that anyone who stood up to him would have Dietrich’s sympathy. He also complained that the generals who surrounded Hitler – Keitel, Jodl and others – had no combat experience. ‘One ought to beat up the whole bunch of them.’ He once again reiterated that he ‘found the Party machine simply disgusting ... I had never anything to do with Party officials as they did not interest me in the least.’ He also made the point that Ursula had never had anything to do with the Party. He displayed disbelief that Hitler had been ‘killed in action’ since he ‘never left his air raid shelter. ’ All these comments were clearly thought to be highly newsworthy and were quickly released to the American newspapers.5 He also, however, expressed some surprising views on the Russians:

‘A very intelligent people; good-natured, easy to be led and also adapted in technical matters; on top of that those huge masses. They were poorly led at the beginning but they learnt quickly. These peasants have a lot of brains and are very amenable. Moreover, their tanks were better. They were less complicated and easier to maneuver. Our tanks seem to have been made by a watchmaker; much too complicated and sensitive. I was really taken aback. These tremendous and modern factories, these agricultural institutions, these granaries – that was simply colossal.

I once had a talk with Molotov and several GPU officers in Berlin. That was highly interesting. They invited me to visit Russia. Too bad I never got around to do it. I spoke to many Russians. They liked it better under Stalin than under the Czar. Even the people on the collectives live all right; they own a piece of land, a cow and they live quite happily.’

It is hard to reconcile this with the atrocities that Dietrich knew had been committed on some of his men, and, while it is understandable that he should have respect for Soviet military power, one can only presume that, fearful that he might be handed over to the Russians to ‘face the music’ over the alleged Kharkov atrocities, he felt that the best way to avoid the Americans doing this was to be flattering in his comments.

On 11 June, he was given a more thorough interrogation, this time by another interrogator, Lieutenant Rolf Wartenberg. This particular interrogation report6 has already been quoted at length since it gives Dietrich’s detailed comments on the campaigns in which he had taken part. One has the impression that Wartenberg was less taken in than his predecessors or, on the other hand, had a much more hostile attitude to his subject.

‘The notorious SS general displayed a forceful personality, which at times suggested a brutality which is said to be part of his nature. He seemed, moreover, to be continually conscious of his own personality, his position and his deeds. He spoke freely and willingly, always stressing the subject of honesty, which he presents as an ideal by which he and his troops were always guided. Though obviously a man with common sense, he showed little intellectual quality during the interrogation. He is very anxious to appear as a purely military man, whose connection with politics was either slight or non-existent. Like so many other German generals, he does not hesitate to blame others for the events which occurred. The playing-down of his own non-military activities, however, does not alter the record of his longtime connections with the Party, with Hider, and with the Allgemeine-SS.

His interest and devotion to military matters seems to be genuine.'

Details were given in the report of his life history and in it he still maintained one or two untruths about his early life. He claimed that he was a butcher before he succumbed, as a youth, to the Wanderlust, and asserted that he had joined the 1st Bavarian Uhlan Regiment in 1911. It is, however, noteworthy that the only decoration specified in the very brief summary of his First World War experience was theKampfwagenzeichen (Tank Combat Badge), which his eldest son still possesses and says that it was one of the awards of which his father was always most proud. The report, however, also says that he commanded one of the ‘few German-built tanks’, which must imply the A7V, again a total untruth.

It was the first time that he was directly questioned about Malmédy and, as has previously been written (Page 156), he denied all knowledge of it, although he did say that four American prisoners had been killed in his corps at Caen during the Normandy campaign, but that this was after the bodies of similarly killed German prisoners had been found. He had initiated an investigation, but since the commanding officer of the unit responsible had been killed, it did not get very far, but a report had been sent to the Foreign Ministry. This incident presumably referred to the killing of Canadian prisoners by theHitlerjugend for which Panzer Meyer was about to come under investigation. Dietrich concluded his remarks by declaring that ‘As an honest soldier, I do not kill prisoners’.

Pressure was already being applied from Washington to locate and bring to book all those involved in the Malmédy massacre. Otto Kumm, who was at Augsburg at the same time, recalls:

‘I had to show my hands and the interrogator said: “blood, blood, everywhere.” I think he was Jewish; he had a Frankfurt dialect and wore a US uniform, when he realised that I was the commander of the Leibstandarte he accused me of being responsible for Malmédy. Then I told him that I was not with the Leibstandarte at the time, but was commanding the Prinz Eugen. He said, “then you have killed 500 million Yugoslavs. You are a war criminal.” I replied that there never were 500 million Yugoslavs, but if you say 50,000 people were killed, then you could be right, but they were killed in battle and nothing else.’7

Gradually all surviving members who had been with the Leibstandarte in the Ardennes were gathered together, as well as the staffs of I SS Panzer Corps and Sixth Panzer Army. In the meantime, Dietrich was again moved, on 13 July, to Wiesbaden. Here the interest in him was not so much on account of any war crimes in which he may or may not have been implicated, but more as part of the efforts of the Western Allies to piece together exactly what had happened in the campaigns in Western Europe during 1944-45. For the Americans, it was the Ardennes which was of greatest interest and the Shuster Commission was charged with investigating the battle from the German side. Dietrich had been interviewed prior to the Shuster Commission beginning its work, on 10 July, just before he left Augsburg. This interview8 appears to have been carried out on behalf of Eisenhower’s Chief of Intelligence, General Sir Kenneth Strong and was concerned with the formation of Sixth Panzer Army and its preparations for the Ardennes offensive. The unknown interviewer commented:

‘Gen Dietrich has been described by interviewers as a crude, loquacious, hard-bitten, tough man whose statements are often inaccurate – yet also a man having a great deal of common sense. His fellow officers, the more class-conscious of whom were often shocked at Dietrich’s language and behaviour, attribute his meteoric rise in the Army to his party connections.’

What is significant about this statement is that the interviewer clearly did not differentiate between the Waffen-SS and the Army. The main interview for the Shuster Commission was carried out by 1st Lt Robert E Merriam at the United States Forces European Theater (USFET) Interrogation Center at Oberursel over 8-9 August.9 Merriam worked through an interpreter and covered the formation, organisation and initial deployment of Sixth Panzer Army, as well as its role in the campaign. He seems to have been even less impressed with his subject than his predecessor:

‘Gen Dietrich is regarded with low esteem by his fellow officers. He did not seem to have a grasp of the operations of his Army in the Ardennes and was unable to present a comprehensive picture of the happenings, even in the most general terms … there are a number of obvious errors in the answers provided by this former chauffeur. ’

What made Dietrich’s mental shortcomings even more marked was the interview which Merriam had with Fritz Kraemer a few days later, which clearly went extremely well, with much information being gleaned.10

Finally, it was the turn of Milton Shulman on behalf of the Canadian Army. He questioned Sepp Dietrich at length towards the end of August 1945, mainly about the Normandy campaign, which was of prime interest to First Canadian Army, but also about his whole life and views.11 One has the impression that this was a much more relaxed affair than the US interviews, probably because the Canadians were not specifically ‘gunning’ for Sepp over war crimes, and one can detect a degree ofsimpatico between interviewer and interviewee. Shulman commented that Dietrich’s ‘position as the senior military officer of the Waffen SS has made him the favourite whipping post of both the Allied press and the German General Staff. Noting the blame that the press had laid on him for atrocities at Kharkov and in the Ardennes, he observed that the General Staff ‘have ridiculed his military skill, his inept leadership, his rough, uncouth personality, his swift climb to high rank with the helping hand of the Nazi Party’. Yet, the Party machine had created an ‘almost legendary figure whose exploits as a fighting man of the people rivalled if not surpassed, that other popular National Socialist figure, Erwin Rommel’.

‘A few moments conversation with the man explains to some extent this reputation. Physically “Sepp” Dietrich is the antithesis of what Hitler would like to have us believe was the Aryan superman. Short, about 5'7" tall, squat, a broad, dark face dominated by a large, wide nose, rapidly dwindling hair, he resembled more the butcher that he started to be back in 1909 than the general he became in 1933. Born near Memmingen, Swabia, he possesses a rich Bavarian accent that no amount of Berlin society has been able to refine of its rough, natural tones. His vocabulary, for which he constantly apologised, is replete with the down-to-earth words of the foxhole and beer cellar, and it is easy to envisage that his language would shock men like Rundstedt and Brauchitsch, who represented the well-educated, class-conscious General Staff. He is garrulous and conceited, and was eager to impress his interrogators as a soldier free from the political intrigues of National Socialism. A flair for the dramatic in gesture and speech, and a crude sense of humour, coupled with a forceful energy that could be hard and ruthless, undoubtedly enabled him to achieve his meteoric rise in the SS.’

He noted that Dietrich’s Army colleagues contemptuously referred to him as the Wachtmeister [cavalry/artillery sergeant-major], but somewhat curiously likened him to Rommel, in that his education and capabilities could not adequately cope with commands above that of a division. Yet, unlike other Waffen-SS commanders like Meyer and Wisch, ‘whose eyes still burn with devotion to their Führer’, Shulman saw Dietrich as a disillusioned man. ‘His open criticism of Hitler, whom he constantly referred to as Adolf, was not merely that of a man trying to get out from under, but the net result of a bitter and chastening experience.’ Once again, he repeated his awe and praise of Soviet military might, but pointed out that the average Russian had almost nothing. Like other captured German generals were saying to their interrogators at the time, Dietrich expressed deep concern over the shadow of the Soviet bear spreading westwards. ‘If Germany goes Communist, France will follow. England, Germany and America must create an international organisation to hold the Russians on the Elbe. This can be done if we build up our plane strength, for the Russians are not good fliers.’ He made flattering comments about the fighting qualities of the Canadians and said that he wanted to get away from Europe, probably to Canada and start again with the RM 25,000 which he had saved. He concluded by saying: ‘You cannot imagine how sick and tired we are of war. You can never know how it felt to fight for three years knowing all the time that your side had already lost.’

Throughout this time, efforts had continued to gather up all those who might have had any connection with Malmédy. During October 1945 some one thousand members of Peiper’s command were gathered together in a special annex of the civilian internment camp at Zuffenhausen, near Ludwigsburg. Others, too, like Otto Kumm, were also sent there. He remembers that:

‘…it was entirely overcrowded. We hardly had any food. We were almost starving. We slept on wooden plank beds. Some of us were so undernourished that they could hardly get up. For months, we had turnip soup for lunch and half a potato for dinner. Deliberately they collected heaps of food outside the fence, which was burnt once a month in front of our eyes.’12

If this was so, it was clearly used as a means of breaking down resistance so that concrete evidence of the massacre could be obtained and the culprits identified. It was, however, hard going, for no one was willing to talk. Dietrich was kept separately, spending five weeks at Oberursel before, on 5 November 1945, being sent to Nuremberg. Here it was intended to use him as a witness in the main war crimes trial of major Nazi figures, but he was never, in fact, called. Nevertheless, he remained at Nuremberg until 16 March 1946 when he was removed to Dachau to finally join those on whom suspicion of active involvement or complicity in the Malmédy affair had fallen were now quartered.

Here Dietrich found Kraemer, Priess, Peiper and some 120 of his officers and men. Indeed, the only person missing in the chain of command was Wilhelm Mohnke, whom the Russians would not give up. This was also frustrating for the British, who especially wanted to question him over the Wormhoudt massacre of May 1940. Lt Col A P Scotland, who headed the British War Crimes Investigation Unit, did, however, interview Dietrich at this time and was not impressed, noting that he ‘cut a decidedly sorry figure’ and ‘disclosed a miserable wreck of a personality during his interrogation’.

‘In wailing tones, repeating his words constantly, all he could say was: “I spent the day in a ditch” ... “I know nothing of any shootings” ... “I spent the day in a ditch”.’

No case filled Colonel Scotland with greater frustration than this one. He was convinced that Mohnke was the real culprit, but could not obtain prima facie evidence, let alone Mohnke himself. Indeed, Mohnke remained in Soviet captivity until the mid 1950s and now lives undisturbed in Hamburg. The author’s efforts to contact him met with a ‘wall of silence’. Scotland was convinced that it was this which had made it so hard for the Americans to break down the Malmédy suspects.13 It was all bound up in the SS oath ‘my oath is my loyalty’ which meant loyalty not just to the state but also to fellow SS men, and this included not informing on them.

Five days before Dietrich arrived at Dachau, Peiper had made a statement to his interrogators which marked the breakthrough, as far as the prosecution was concerned. He stated that on 14 December 1944 he had visited theLeibstandarte headquarters and been handed written orders for the offensive, as well as having a short conversation with Mohnke.

‘I can remember that in this material, among other things, was an order of the Sixth SS Panzer Army, with the contents that, considering the desperate situation of the German people, a wave of terror and fright should precede our troops. Also, this order pointed out that the German soldier should, in this offensive, recall the innumerable German victims of the bombing terror. Furthermore, it was stated in this order that German resistance had to be broken by terror. Also, I am nearly certain that in this order was expressly stated that prisoners of war must be shot where local conditions should so require it. This order was incorporated into the Regimental Order. . , ’

Peiper than went on to say that he held a meeting of his subordinate commanders, but ‘I did not mention anything that prisoners of war should be shot when local conditions of combat should so require it, because those present were all experienced officers to whom this was obvious’. He recalled that the order had been signed by Sepp Dietrich. ‘I know, however, that the order to use brutality was not given by Sepp Dietrich out of his own initiative, but that he only acted along the lines which the Führer had expressly laid down.’14 Dietrich was confronted with this testimony and on 22 March made a sworn statement that he had given such an order in so far that the Ardennes offensive represented ‘the decisive hour of the German people’ and that it was to be conducted with a ‘wave of terror and fright’ and without ‘humane inhibitions’.15 What had suddenly broken Peiper and Dietrich down?

On 6 June 1948 Peiper made a sworn statement to his lawyer, Doctor Leer, at Landsberg.16 In it he told of the interrogation methods used by the Americans. At his first interrogation, at the US Third Army Interrogation Center at Freising in August 1945, he was told that he was ‘ the GI enemy No 1 ’. In September he was moved to Oberursel and confronted with survivors of the massacre, but no formal interrogation took place. He was, however, placed in solitary confinement for seven weeks and, at one point, spent 24 hours in a cell which was heated up to 80 degrees Celsius. He was then moved to Zuffenhausen, where the interrogations began in earnest and were conducted by 1st Lt Perl. The line the questioning took was that the American people had already found Peiper guilty and therefore he should do the decent thing and take full responsibility. Imprisoned for five weeks in a ‘nearly completely dark cellar’, not allowed to wash or shave during three weeks of this period, denied food for two days, ‘robbed and insulted’, Peiper eventually gave way on the condition that his men would be released unpunished, which was refused. Peiper than asserted that Lt Perl had warned him that if he chose to commit suicide and left a note claiming full responsibility, Perl would testify that Peiper had had nothing to do with the massacre. “‘The Führer’s Loyal Body Guard” will not come [sic – get] off so easily.’ The fourth phase took place at Schwäbisch Hall during December 1945-March 1946. Towards the end of this period, Peiper was told that Dietrich, Kraemer and Priess had already confessed. But then Perl declared: ‘We know you had nothing to do with the crossroads. We don’t want you. We want Dietrich!’ This indicated that Dietrich had not yet confessed. Peiper was now told that an extract had been found in the Sixth Panzer Army operation order, which stated that prisoners would be shot under certain circumstances and that seven or eight of Peiper’s officers would confirm it. The extract itself was never ever produced, even in court. Confronted by his former adjutant, Hans Gruhle, who admitted the existence of this order, Josef Diefenthal, who had commanded 3rd Battalion 2nd SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment and admitted giving the order to shoot the prisoners, and others, Peiper finally broke down.

In a further series of sworn statements given at Landsberg in 1948 by some of Peiper’s men, it was asserted that they themselves were broken through torture.17 Mock hangings, beatings and hooding, mock trials and threats against families living in the Soviet Zone of Occupation were all apparently employed. Otto Kumm, although he was not himself physically tortured, states that at Dachau he certainly recalled that one Gottlieb Berger, who was not a Malmédy defendant, had had lighted matches forced under his finger nails.18 Dietrich himself also asserted that he had been kicked while being led to interrogation.19

It is extremely unlikely, though, that it was torture or, indeed his treatment by his captors, which made Dietrich break down. More likely, confronted with confessions by Peiper, Kraemer, Priess and others, Dietrich felt duty-bound to shoulder the major share of the responsibility for the atrocities, but, as we shall see, the majority of these confessions, including Dietrich’s, would be retracted once it came to the trial. The allegations of torture would also later be a major factor in the subsequent controversy over the trial.

Dietrich, himself, appears to have only spent a short time at Schwabisch Hall (6-25 April), when the Malmédy interrogations were mainly carried out,20 but while here, on 16 April, he was formally arrested and charged by the United States Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) and on 9 May, after his return to Dachau, he lost his Prisoner of War status, as did the other seventy-three defendants. On 16 May the Malmédy massacre trial was formally opened.

Officially known as Case No 6-24, United States versus Valentin Bersin et al – formerUnterscharführer Bersin was the first man on the alphabetical list of the accused – the trial took place at Dachau before a General Military Government Court. President of the Court was Brigadier General J T Dalbey and the members of the court consisted of seven US Army officers of field rank, assisted by a legal adviser, Colonel A H Rosenfeld. The prosecution team was the same that had carried out the investigation over the previous months, and was led by Lt Col Ellis and included Lt Perl. The defence had seven somewhat unwilling German lawyers, but also a man, who was to be instrumental in later making the case acause celebre in the United States, Lt Col Willis M Everett Jr, an Army lawyer from Atlanta, Georgia. The accused were formally charged with violation of the Laws and Usages of War in that they, as

‘German nationals or persons acting with German nationals, being together concerned as parties, did, in conjunction with other persons not herein charged or named, at or in the vicinity of Malmédy, Honsfeld, Büllingen, Ligneuville, Stoumont, La Gleize, Cheneux, Petit Their, Trois Ponts, Stavelot, Wanne and Lutebois, all in Belgium, at sundry times between 16 December 1944 and 13 January 1945, willfully, deliberately and wrongly permit, encourage, aid, abet and participate in the killing, shooting, ill-treatment, abuse and torture of members of the Armed Forces of the United States of America, then at war with the then German Reich, who were then and there surrendered and unarmed prisoners of war in the custody of the then German Reich, the exact names and numbers of such persons being unknown but aggregating several hundred, and of unarmed allied civilian nationals, the exact names and numbers of such persons being unknown.’

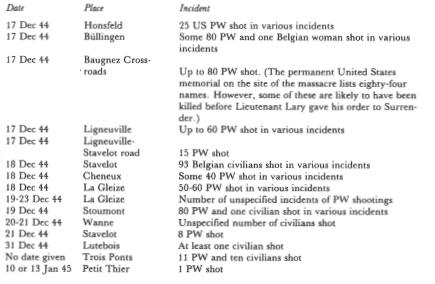

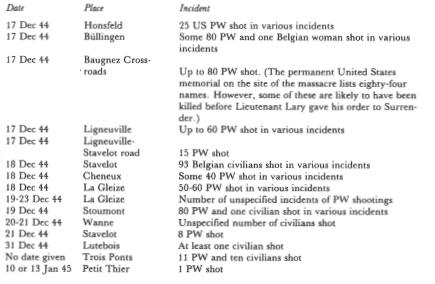

Thus, the trial was not devoted merely to the incident at the Baugnez cross-roads on the afternoon of Sunday 17 December 1944, but to a whole series of alleged atrocities. These were detailed by the prosecution and are best represented in a tabular form.

All these violations were attributed to Kampfgruppe Peiper, and it should be noted that none of the other formations of Sixth Panzer Army had their names directly connected with other Ardennes war crimes trials. The truth of the matter was that the Baugnez Crossroads incident had completely blotted the minds of American officialdom and general public alike. The other incidents were unearthed during the pre-trial investigation, but no one seems to have asked the question as to why, if Dietrich had issued an Army order that prisoners could be shot in certain circumstances, that it was only oneKampfgruppe which took advantage of this. With four supposedly hardened SS Panzer Divisions under his command, one would have expected other incidents involving other units to have come to light.

Be that as it may, within a few days of the opening of the trial the United States Press, having heard the general case for the prosecution, had already returned their verdict. ‘These seventy-four will get their punishment … because the conscience of humanity has not quite been stilled’, as one newspaper put it.21 In Dietrich’s case the evidence used against him was his own admission of 22 March 1946 and those of Kraemer, Peiper and Gruhle. Dietrich, however, withdrew his admission that he had stated that prisoners could be shot, although admittedly, part of the Sixth Panzer operation order did contain the following:

‘Action by armed civilians must be anticipated. These civilians in general belong to the movement known as the Resistance Movement. It is likely that roads will be mined and charges placed on railways and bridges. Headquarters, telephone lines and convoys etc must be guarded … Resistance by armed civilians must be broken.’22

Kraemer, too, withdrew his previous confession and stated that the operational order dated 8 December 1944 referred to above specifically stated that all loot and prisoners of war were to be collected quickly and that corps were to attach special escort units to forward detachments, who would use returning empty logistic transport to get the prisoners to the rear. Collection of prisoners was not to be taken on by forward units themselves, who were to send them back to collecting points. As for the Malmédy massacre, he stated that one of his staff officers had heard about it on the radio from Calais on 20 or 21 December and that a radio message had been sent out reminding units that the Army Commander prohibited all actions and conduct in violation of the laws of war. TheLeibstandarte had reported on 26 December that no prisoners had been shot in its sector, although it must be pointed out that, as Peiper himself said, radio communications between him and Divisional HQ over the period were, at best, poor. The Chief of Staff of LXVII Corps, who appeared as a witness for the defence, stated that he had received an order from Kraemer specifically stating that the mistreatment of prisoners of war was forbidden. Dietrich Ziemssen, who was chief operations officer of theLeibstandarte at the time and who also was a defence witness, confirmed this, as did Hubert Meyer, Chief Operations Officer of theHitlerjugend. Rudolf Lehmann, in his capacity as Chief of Staff of I SS Panzer Corps, also supported Kraemer’s statement about prisoner collecting points. Georg Maier, who was on the staff of Sixth Panzer Army at the time, Ziemssen, Lehmann and Kuhlmann, who commanded theHitlerjugend?s Panzer regiment, also affirmed that Dietrich’s special order of the day had not contained anything about a wave of terror or any suggestion that no humane inhibitions were to be shown. While Dietrich had said in prejudicial statements that he had been reflecting Hitler’s words at the Bad Nauheim conference on 12 December 1944 in his order of the day, Priess, who was present at the conference, said that Hitler had never mentioned anything of this nature, nor did he speak of prisoners of war, and neither did Dietrich’s order of the day, which he regarded merely as propaganda. He did, however, accept that the operation order did mention the possibility of armed civilians being encountered. He also said that the logistic order, which had been signed by Kraemer, did refer to the method of getting prisoners of war to the rear. He also, however, stated that under German principles, a corps commander was not responsible for the behaviour of his troops and that the highest ranking officer who was held to be so was the divisional commander. One cannot help, however, but suspect that he declared this as a means of trying to save his own skin.

The fact that so many officers asserted that the question of what to do with prisoners had appeared in the logistic order does, however, conflict with a point made by the prosecution at the trial. Apparently, when Dietrich held his formal orders group on 14 December, one person present asked about prisoners, thinking that Dietrich had missed this point out. Dietrich is supposed to have replied, and he did not deny it at the trial: ‘Prisoners, you know what to do with them.’23 Dietrich himself said that he implied that the Laws of War were to be respected, although he could have also been referring to the fact that this topic was covered in the logistic order. Jacques Nobécourt, however, interviewed a Wehrmacht colonel who had been present at this conference, albeit the interview took place in the mid-1950s. This colonel stated that:

‘Addressed to the generals and senior officers of the Waffen SS and in the atmosphere of the time, a phrase of this nature can mean only one thing: get rid of the prisoners. And that is the way that it was interpreted.

In fact the Americans were at fault in condemning to death only those who committed the crimes and not Sepp Dietrich. He was the man really responsible for the Malmédy massacre and the way in which I SS Panzer, the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, shot down civilians throughout their advance, particularly at Stavelot. The least that can be said is that the commanders were letting their men run riot.’

Thus, there is a conflict of evidence and the prosecution were unable to produce primary documentary evidence that Dietrich had specifically said or implied that prisoners could be shot. On the other hand, it could be argued that such evidence was destroyed at the time for fear that it would be incriminating, bearing in mind that it was clear to all but the most fanatical Nazi that the war was by then lost.

The key figure in the trial was undoubtedly Joachim Peiper. He, too, rescinded his extrajudicial statements, and repeated what the others had said about prisoner collecting points and that armed civilian resistance was to be expected. Preiss had held a conference on 15 December 1944, which Peiper attended and at which Dietrich’s order of the day was read out, but it was merely an appeal to German soldiers, with nothing on prisoners of war or civilians. Skorzeny was present and the outline of OperationGreif, with its object of spreading panic and confusion within the American lines, was explained. Nothing was verbally raised on prisoners of war, and Peiper’s own operation order was concerned merely with tactical matters. This seems to have been supported by his adjutant Gruhle. Others said that theKampfgruppe HQ held two meetings at the command post – a hunting lodge in Blankenheim Forest – on 15 December and the subject of prisoners of war and civilians was not mentioned. This seems surprising, bearing in mind Peiper’s mission. One would have thought that, bearing in mind the vital time factor with regard to the Meuse bridges, there would have been some emphasis on not allowing the momentum of the advance to be slowed down by becoming involved with prisoner handling.

Nevertheless, that at least some of the incidents took place there is no doubt. There were the frozen corpses discovered by the Americans at the Baugnez cross-roads, none of them with any weapons found by them. A further eight bodies were found behind the Hotel du Moulin at Ligneuville and from their postures there was little doubt but that they had been executed. Furthermore, the bodies of twenty-three Belgian civilians – men, women and children – were discovered outside a house in Stavelot. There were, too, the witnesses. Survivors of the Baugnez cross-roads massacre, including Lt Lary, were there to testify in court, and Belgian civilian witnesses to some of the incidents had also been located. In other cases, though, the prosecution’s case looked distinctly weak. La Gleize was the most prominent example of this. The defence was able to produce both McCown (now a lieutenant colonel) and a Belgian curé, both of whom were positive that no killings of American prisoners had taken place there.

Most of the junior ranks of Kampfgruppe Peiper who stood accused of these atrocities had said in their extrajudicial sworn statements that they had shot prisoners on the orders of their superior officers. Some, significantly, did not take the stand during the trial, while others stuck to their extrajudicial statements, but yet others denied that they had been at the scene of the alleged atrocities at the time at which they took place, or had witnessed them. Many of the defendants, however, testified that they had been subjected to beatings, hoodings and mock executions during the pre-trial investigation, which, apart from the beatings, was not denied by the prosecution, and it was this that had caused them to make false statements. Typical of these was the case of formerObersturmführer Franz Sievers of the 1st SS Panzer Engineer Battalion, who would receive the death sentence for his part in the killings at Baugnez cross-roads.

‘The accused testified that after solitary confinement for three months, he was interrogated on 25 February 1946 at Schwäbisch Hall for the first time. He was asked his name and upon replying “Sièvers”, he received a blow in the mouth. Then he was pushed into a cell with his face toward the wall where he received a blow in his right hand. Shortly afterwards a hood was torn off his face. Two interrogating officers were standing in the cell. The accused was told to bare the upper part of his body. When he took off his shirt, they said: “You pig, you smell of perspiration. You haven’t washed lately. Pick up your arms. ” The accused stated he had not had an opportunity to bathe in the last twelve weeks. He only received two or three litres of water daily for washing. The accused was pushed against the wall by Mr Thon who said that he was the public prosecutor. The accused was told that he had shot at prisoners of war with a bazooka. The accused further testified that Mr Thon told him he would bring a vial or a rope so that the accused could finish his life. The accused responded that it was not necessary as he did not have any prisoners of war on his conscience. When Lieutenant Perl wanted to give him some tobacco for a cigarette, Mr Thon jumped up immediately and said: “That guy’s not going to get any tobacco. He will have to confess first.” Then he was confronted with several men of his company. The first one that was led in was Sprenger [Gunter Sprenger was in Sievers’ Company and was later also sentenced to death], who was put under oath in the regular manner and then asked if he knew the accused. The accused was then put into a machine room. Lieutenant Perl showed him some men working there. He said they were all from the Adolf Hitler Division and now had a good life because they had confessed. On the way back, Lieutenant Perl said: “Sprenger shot upon your order and he will only get six to eight months and then he’ll be free again, and you acted under orders of Peiper and carried out the order. What could happen to you? You are just a little Obersturmführer. We don’t even want you. We dont even want Peiper. We want Sepp Dietrich and we’ll have a trial for him about which the world will gaze with wonder.” The accused was moved by that and made his first statement which was immediately torn up by Lieutenant Perl because he was not satisfied with the contents. The accused then wrote another statement which was dictated by him [Perl]. He was then taken to the famous death cell by Lieutenant Perl. In the afternoon, the accused was again called out for interrogation. He still did not know of any order [to shoot prisoners]. He finally became tired of this treatment and wrote out another statement. The accused frequently protested and once got up and said that he would not have any more dictated to him. Lieutenant Perl kicked him and told him to sit down and write or he would be beaten. The accused asked Lieutenant Perl for permission to relieve himself, but this was refused. The accused was again interrogated on 11 March 1946. He was told to change his statement and, on his refusal, was threatened with hanging. The accused was compelled to stand in the hall for four hours with a hood on his head. The interrogating officer came quite often and asked his name. When the accused did not answer he was hit in the stomach.’24

Needless to say, in court both Perl and Thon denied striking the prisoner. Another defendant, when asked why he had made a self-incriminating statement said in court that, having undergone treatment like this, ‘I was in a spiritual and mental state such that nothing seemed to matter to me.’25

Colonel Everett seized upon the fact that these extrajudiciary statements, which formed the main cornerstone of the prosecution’s case, were inadmissible because they had been obtained through trickery and coercion, and went further. Since the accused were prisoners of war, then the Geneva Convention applied and they were entitled to be tried by the same courts and under the same procedure as in the case of members of the armed forces of the occupying power. It would seem here that the members of the court were guided by Wheaton’sInternational Law, which stated:

‘If men are taken prisoners in the act of committing, or who had committed, violation of international law, they are not properly entitled to the privileges and treatment accorded to honorable prisoners of war. ’26

This, though, could only be proved at their trial and hence could only apply once they had been found guilty. Thus, it could be argued that removing the prisoner of war status from the defendants prior to the trial was an illegal act. But, as part of the preparations for war crimes trials, a United States Joint Chiefs of Staff directive issued in the summer of 1945 had empowered the Commanding General United States Force’s European Theater (USFET) with the setting up of courts separate from those trying offences against the occupation and that they should adopt ‘fair, simple and expeditious procedures designed to accomplish substantial justice without technicality’.27 The outline of procedure to be followed by such courts was laid down by the USFET Judge Advocate in November 1945 and, among other rules it laid down, was that:

‘To admit in evidence a confession of the accused, it need not be shown such confession was voluntarily made and the Court may exclude it as worthless or admit it and give it such weight as in its opinion it may deserve after considering the facts and circumstances of the execution.’28

But while the rules of evidence, as recognised in American and British municipal law trials, were not applicable, and, indeed, the question of involuntary confessions does not seem to have been catered for in the Judge Advocate USFET’s rules of procedure, American justice did recognise that:

‘… while artifice and deception will not in themselves render a confession involuntary, if there are combined with the deception any inducements which excite hope of benefit from the making of the confession or fear of consequences if he does not make such a confession, the confession is involuntary.’

It was, however, up to the court to decide whether such inducements had been made, which would thus render the confession involuntary and hence inadmissible. 29 As for extrajudicial statements against co-accused, Everett pleaded that in British and American municipal criminal law courts these were inadmissible, but the prosecution pointed out that in this case the defendants were not ‘honorable’ prisoners of war, and hence this rule did not apply. This was upheld by the court.30

It would seem, therefore, that the rules of procedure were being adapted as the court saw fit and the members were fully aware of the pressure in the United States at large to find the defendants guilty. It was thus not surprising that all except one, who was discharged on 11 July, were found guilty, and they were sentenced on 16 July. No less than forty-three were sentenced to death by hanging and the remainder to varying terms of imprisonment, from life to ten years. Dietrich himself was sent down for life, Kraemer for ten years, Priess for twenty years and Peiper received the death sentence. That they recognised the efforts made by Everett on their behalf was reflected in the fact that Kraemer wept openly during his summing up on 11 July and Dietrich shook him by the hand and thanked him afterwards.31

On 17 July, the day after the end of the trial, Dietrich and the other defendants arrived at the fortress of Landsberg. How much the poetic justice of this struck the new arrivals, if at all, in view of the fact that this was where Hitler had writtenMein Kampf, while imprisoned there after his 1924 Munich trial, cannot be gauged. Perhaps, more to the point, it appeared to many that Landsberg would be their last home on earth. Yet, they did have one ally on their side. Willis Everett was convinced that there had been a miscarriage of justice. The Malmédy affair had by no means come to an end.