ON FEBRUARY 1926, MARLENE DIETRICH ASsumed the role of Lou Carrère in Hans Rehfisch’s social satire Duell am Lido. Cast as an amoral girl tottering on the brink of the demimonde, she arrived at the first rehearsal and was told by director Leopold Jessner that she looked just right in her own outfit—silk trousers, a dark jacket and a startling monocle—and that she should wear all these in the performances. He may not have known that she had come directly from an all-night frolic at a transvestite bar called Always Faithful, whose patrons were certainly not. Dietrich may have taken her performance cue from that place, too, for she played Lou as frantically decadent. “The role should have been acted by Marlene Dietrich not in a demonic revelry but icy-cold,” remarked critic Fritz Engel.

From that season on, she was a well-known public presence, and not at all because of her professional accomplishments. Known in seedy Kurfürstendamm bars as well as at elegant dances sponsored by producers and musicians, Dietrich was typical of many Berlin actresses —freewheeling and unconventional in her conduct and eager to meet those who could advance her career; they were often more approachable at night, after they’d had several whiskeys and some cocaine. At such times, however, she always kept a clear head.

Often, as actress Elisabeth Lennartz recalled, Dietrich got attention at restaurants and cafés by “wearing neither bra nor panties, which was very modern and daring.” Dancer and actress Tilly Losch, a leading doyenne of the Berlin lesbian bar scene, recalled that Dietrich was no stranger to such places. “It was chic for girls not to be feminine. I knew Dietrich in those days and she was a tough little nut. But unlike the others, she somehow looked glamorous.” A photograph of the time shows Dietrich as glamorous indeed in a gentleman’s smoking jacket at a ladies’ supper club, flanked by Leni Riefenstahl (soon to be Hitler’s documentarian with her films Triumph of the Will and Olympiad) and the Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong.

In lounges, cabarets and jazz clubs, however (as Gerda Huber and Grete Mosheim, among others, confirmed), Dietrich had a reputation for combining the most outrageous dances, jokes and sexual capers with unbending opposition to drugs and excessive drinking. She was, in other words, a curious combination of her mother’s Prussian upright moralism and her own sturdy, antic individualism. Käte Haack recalled a formal ball in the mansion of Eugen Robert, director of the Tribune Theater, attended by Reinhardt, playwright Ferenc Molnár, the actors Peter Lorre and Conrad Veidt, and Carola Neher (soon to star in the original production of The Threepenny Opera).

Only one woman stood out: Dietrich, who appeared and took the hand of Carola Neher, who was also a great beauty. And then the two of them danced a tango. It was an unforgettable sight, and the entire crowd, astonished, made room and watched.

The tango was of course a dance of considerable style, and it drew attention by its controlled, almost stoic eroticism. Dietrich and Neher glided, swooped and dipped without ever unlocking a breathless embrace. The bystanders cheered.

But there were other ways of attracting attention. Elli Marcus, known for her celebrity photographs, was approached by Dietrich with the blunt request, “Take some pictures of me that will make me a star.” Warily, Marcus complied and Dietrich sat obediently for three days of photography; despite the pleasing results, fame still eluded her.

At home, Sieber at first took his wife’s eccentric liberties calmly, as if they were an actress’s transient fancies or a phase from which she might emerge. Indeed, Dietrich openly discussed her casual amours, which included men from film studios with whom she spent an occasional night, actors from the theater who she thought required a little attention, and those like Anna May Wong and Tilly Losch, who were clever, amusing and exotic companions. She did not proffer sex as barter, to win a role or a favor; it was simply an acceptable form of flattery and a way of being appreciated. From men she was perhaps winning the approval she had been denied by her father and stepfather, while intimacy with women was always natural and easy for her.

IN LATE SPRING 1926, DIRECTOR ALEXANDER KORDA cast Dietrich in the role of a pretty, sophisticated society girl in a film showcasing his wife Maria. In Eine Du Barry von Heute (A Modern Du Barry), billed oddly as Marlaine Dietrich, she had only three brief scenes as a nameless coquette—but she nevertheless revealed a real flair for comedy. After ordering a new dress that requires time for alterations, she sees the shopgirl wearing it at an elegant restaurant that very evening. Furious, she demands that her escort take her away at once, and her quick shift from surprise to annoyance to prissy outrage is comically acute. Next morning, languishing in bed, she telephones the dress shop to demand the clerk’s discharge, only to be told the girl has already resigned (and become an overnight social sensation). Her understated fury—conveyed by simply narrowing her gaze and slowly pursing her lips—is a model of discerning adult acting in silent film.

Despite the small role and modest income—Dietrich was paid only three hundred marks, which was one percent of the star’s salary—she agreed that August to appear for Korda as a mere dress extra for the party scenes of a comedy called Madame wünscht keine Kinder (Madame Wants No Children.) This she accepted on condition that Rudi be hired as a production assistant, a courtesy won through the intercession of cinematographer Karl Freund, who years later in America was the cameraman for the television series I Love Lucy.

But there was no time—nor did she have the inclination—to be despondent over a negligible film career. In late August, Dietrich was busy rehearsing daily at the Grosses Schauspielhaus when an ailing actress (Erika Glässner) withdrew from Eric Charell’s eighteen-scene musical revue Von Mund zu Mund (From Mouth to Mouth.) This show, which opened September i, was important for several reasons.

First, this was Marlene Dietrich’s initial appearance in a singing role—an assignment for which she did not believe herself well suited and a skill she had hardly refined. Nevertheless, on short notice she worked with Charell (a noted choreographer and director of operettas, revues and folk musicals) and with composer Hermann Darewski. By opening night, Dietrich had learned three songs that were inserted into her spoken material as the show’s mistress of ceremonies. Wearing a bright yellow dress with a long train and rose-colored ruffles at the neck and wrists, she stood—quite still, as she insisted to Charell at dress rehearsal—and sang the undistinguished melodies, barely acknowledging the grandeur of her surroundings or the vast audience. Her apparent detachment created, as she must have suspected, an atmosphere of intrigue about herself and what experience might have been behind the lyrics of the song; she barely regarded her audience, half-closing her eyes and never smiling until she walked, slowly and with a kind of muted eroticism, along the extended ramp over the orchestra pit. With one glance and a hushed word, as actor Hubert von Meyerinck recalled, she communicated more than any performer who cavorted wildly in the show.

It was with the delivery of her second song in Von Mund zu Mund that Dietrich brought the audience to a standing ovation. Altering her stance and tone to present a slightly tense, perky sexiness, she revealed a voice not of great beauty or warmth, but one with unusual spirit, range and subtlety. A recording released the following year was a minor sensation among private collectors in Berlin, along with her renditions of “Wenn ich mir was wünsche” (patently modeled on American blues singers) and “Leben ohne Liebe,” sung in a disarmingly innocent style, rather like a sad, distracted nightclub performer offering a weary conviction that “You can’t live without love,” and that an abandoned woman knows this better than anyone.

WITH THESE FIRST RECORDS, MARLENE DIETRICH was about to join an array of German actresses who tried to sing (and singers who tried to act). Many, like her, had distinctive styles, but many were facile mimics of other Europeans or Americans who vocalized with more or less a personal manner. Among the most famous was Lilian Harvey, the British actress raised in Germany (where she became a star), who was perhaps closest to an accomplished operetta artist when she sang onstage or in film (as in her 1926 film Prinzessin Tralala.) Renate Müller, on the other hand, had a slightly nervous vibrato when she sang “Ich bin so glücklich heute—I’m so happy today,” rather as if she were protesting too much (in fact she committed suicide at thirty). They avoided the blunt attack of those like Fita Benkhoff (who liked to flavor her songs with Americanisms like “Oh, baby!”). On the other hand, Trude Hesterberg was certainly one of the most trained voices—almost operatic—and Evelyn Künneke was one of those most influenced by American popular song.

But Zarah Leander and Claire Waldoff were perhaps the most famous, controversial and prominent singers at the time and later—and the most influential on the development of Dietrich’s singing style. Leander had an astonishingly smoky, androgynous baritone, but her delivery was in a strange way strongly, almost severely feminine. When she sang about a pursuit of casual amours (“every night brings me a new stroke of luck”) there was a strain of knowing defeat, of loneliness; just so in a lyric of fatigued waiting (“each night, by the telephone . . .”) or Gallic compromise as she thanked a lover as he (or she) departed (“Merci, mon ami . . .”). Enormously popular, Zarah Leander—with her adult, apparently unemotional but acutely felt trademark of knowing distance—was certainly a model for Marlene Dietrich in the late 1920s. She prepared the way for Dietrich’s delicate balance between eternal romantic optimism and tiresome self-pity.

Much less womanly but equally influential was Dietrich’s co-star in Von Mund zu Mund, the redoubtable Claire Waldoff, a barrel-chested little Valkyrie who—seen in photos and heard on recordings decades later—resembled no one so much as Mickey Rooney in drag. Waldoff’s theatrical songs and recordings, crudely refined in cabaret, were not so much sung as rasped or bleated with an almost painful, choking coarseness that many Berliners loved precisely for its unconventionality. Spitting and punching her way through the measures of “Hannelore” (a paean to a rudely educated peasant girl) or “Willi” (in which she poked fun at the deposed Emperor), Claire Waldoff raged along like a boozy stevedore. An intelligent performer unafraid to offend with her openly gay songs, she also enveloped everything with a self-mocking humor.

In fact—unlikely a pair though they might have seemed—the now occasionally blond Marlene Dietrich and the red-headed Claire Waldoff became lovers (or at least sexual partners) in the autumn of 1926. Geza von Cziffra, Elisabeth Lennartz and Stefan Lorant knew that Dietrich was quite besotted with her new friend, with whom she often dined after midnight, sometimes singing along the Kurfürstendamm or (to the delight of theater patrons) in the alley near the theater. This brand of professional-personal intimacy, however briefly it lasted, was typical throughout Dietrich’s life; it seemed to have its own truth and reward, and when the affair ended Waldoff remained a genial buddy to her. Fritzi Massary, the reigning queen of musicals and operettas at Berlin’s Metropol from 1904 to 1932, later wrote that Dietrich learned from Waldoff to laugh at herself as well as at the pretensions of hypersophisticated audiences.

Dietrich was also (according to Mia May, the leading lady in Tragödie der Liebe) “constantly pursued by people who found her fascinating, [and] she went around with a group of young actresses who adored her. Usually she wore a monocle or a feather boa, sometimes as many as five red foxes on a stole.” Perhaps inevitably, an increasing number of adoring colleagues and theater fans were therefore responsible for Dietrich’s growing self-confidence in Berlin from 1926 to 1930. At a party she gave for friends at home at Christmastime 1926, word circulated that she was going to change her outfit. Käte Haack recalled that Dietrich had ordered an ensemble with seven silver foxes that had just arrived, and she made a second grand entrance, forcing (as she doubtless intended) everyone’s attention on herself. Such tactics often assured that she would be noticed in public, too—at the Cabaret Nelson, for example, a notorious nightspot where high art could be found one moment and low humor the next. On the other hand, she discouraged others from calling attention to themselves. When the actress Lili Darvas admired Dietrich’s fur coat but compared it unfavorably to her own, she was told, “Oh, don’t worry, Lili, dear—no one is ever going to bother to look at you.”

AFTER THE BRIEF BUT MEMORABLE PRESENTATION OF Von Mund zu Mund, Dietrich supplemented her income from late 1926 through early 1927 by rushing through three films. In Kopf Hoch, Charly! (Heads Up, Charly!), she again assumed the small role of a French coquette; in Der Juxbaron (The Imaginary Baron), she had a major comic role as a young woman whose parents hope to marry her off to a nobleman; and in Sein Grösster Bluff (His Greatest Bluff) she was a high-priced prostitute involved in a jewelry theft. In each of these productions were actors (Michael Bohnen, Trude Hesterberg, Albert Pauling) who recalled Dietrich’s thoroughly professional attitude; indeed, she had a lifetime reputation for punctuality and preparedness. She was also remembered for honoring colleagues’ birthdays with cakes or strudels or trinkets—gestures that were certainly sincere but also perhaps reflected her wish to gratify and to be considered generous and thoughtful.

Dietrich was herself pleased when she won a small role in the European premiere of George Abbott and Philip Dunning’s American play Broadway, a tense romantic melodrama still selling out in New York after a year’s run. The premiere was given at the Vienna Kammerspiele on September 20, 1927, where she made a brief appearance as Ruby, a chorus girl in a spicy jazz-age story about speakeasy gangsters, bootleggers, corrupt police and a vaudevillian’s climb to stardom.

The role was almost negligible, but once again Dietrich managed to attract attention by raising her hemline just a trifle higher than the other chorines’ (although there was no dancing). In the first-night audience was Karl Hartl, then in Vienna as executive producer for a movie with characters similar to those in Broadway; two days later, he invited Dietrich to his office and offered her a part in the film Café Electric. “She showed only a mild enthusiasm,” Hartl said years later,

and I had the feeling her heart wasn’t in film. But she accepted, and she showed up the first day with a red suit and a hat like a pot. Marlene knew how to wear clothes of mediocre quality in a way that seemed elegant; her taste and her choice of colors made up for the cheapness of the material.

She accepted the role not only for the salary but also because it was an opportunity to work with the dynamic and popular Viennese actor Willi Forst. As Erni, Dietrich was to be seduced by a young gigolo named Ferdl (Forst), a denizen of the notorious Café Electric, gathering place of pimps and hookers. In a swift blurring of the distinction between art and life, Dietrich and Forst became the talk of Vienna’s café society within a week. “We had to repeat several love scenes between her and Willi Forst,” said Hard. “Considering their romance, this was no hardship for them, and finally she was outstanding.”

The production had another social advantage for her. Igo Sym, also in Café Electric, was a handsome Bavarian actor and musician who taught Dietrich to play the musical saw, a long strip of thin metal like a toothless saw, played with a thickly waxed bow. With her knees grasping the handle of the saw, she bent the metal—more for higher tones, less for lower—and slowly applied the bow to its edge; the sound could be politely described as a kind of mournful vibrato. For decades, Dietrich had a kind of vaguely comic renown in Germany and America as the first lady of this “singing saw,” although she always regarded this talent with absolute solemnity, as if it authenticated her earlier hopes for a career as a concert violinist.

Not long after the Dietrich-Forst romance became an open secret, Rudi arrived in Vienna and demanded that Dietrich end the affair. This was never the judicious approach to take, for it had the predictable effect of confirming her on the independent route she always marked for herself; his wife apparently barely reacted to this entreaty. Rudi had hoped that the responsibilities of motherhood would alter her conduct, but this was a hopeless fantasy. When he then countered that he had the chance for his own extramarital romance—with a darkly attractive young woman named Tamara Matul—Dietrich was delighted and encouraged him.*

“I haven’t a strong sense of possession towards a man,” she said somewhat airily not long after her confrontation with Rudi, “perhaps because I am not particularly feminine in my reactions. I never have been.” This was the closest Dietrich ever came to justifying her continuing marriage to Rudolf Sieber, a relationship that was henceforth always cordial. From 1927 to 1930, the Siebers lived together only part of the time in Berlin (and rarely thereafter anywhere). Dietrich never seriously considered divorce, perhaps because even a nominal marriage forestalled another offer and acted as a kind of protection. But that same year, Tamara Matul became Rudi’s constant companion and an attentive surrogate parent to Maria when her mother was absent.

Before returning to Berlin, Dietrich—acceding to Willi Forst’s fervent request to prolong her Austrian sojourn—took a small role in the satiric play Die Schule von Uznach by Carl Sternheim, Germany’s reigning comic dramatist. After the November 28 premiere at Reinhardt’s Theater in der Josefstadt, critic Felix Salten (author of Bambi) wrote, “Among the girls, Marlene Dietrich was the most refreshing as a beautiful, sensual young woman who rambles on without thinking.”

DIETRICH RETURNED TO BERLIN IN EARLY 1928, arms full of belated Christmas gifts and toys for Maria; she then devoted two weeks to the child’s amusement, taking her to the zoo, parks and children’s pageants. Then she was back in rehearsals for the Berlin opening of Broadway on March 9, and for a celebration in honor of her old boss Guido Thielscher, whose fifty years in show business were marked by a midnight cabaret at the Lustspielhaus on March 27. These two events, following the Berlin premiere of Café Electric (retitled for Germany as Wenn ein Weib den Weg verliert/When a Woman Loses Her Way) and linked to her increasing prominence as a colorful doyenne of theatrical social life, gave Dietrich the widest press exposure she had so far enjoyed.

She still tended to a portliness all too evident on her short frame, and she worried that her nose (which turned up slightly at the tip) made her less photogenic than she would have liked. But her legs were ideal—perhaps because she was now exercising daily with a prizefighter’s trainer who forced her to lie on the floor for hours, pedalling an imaginary bicycle. Casting directors, not to mention most men and many women, were quick to notice the elegant, sensual line of her legs; she could, therefore, risk an even higher hemline than that dictated by mere fashion.

In addition, Dietrich’s partiality for an onstage pose of profound unconcern continued to work wonders for her image. To receive an almost rapt attention Dietrich had only to lean against the scenery, lower her eyes and light a cigarette with utter indifference to everyone round her. In a comic role, this gave her a deadpan appearance and seemed somehow all the funnier; in a serious part, she seemed more than ever a mysterious, eternally ineffable presence. By such tactics, she effectively stole scenes and was immune to criticism from other players. She was, in other words, refining the theatrical counterpoint of creative indolence to a highly successful technique.

IT WAS PRECISELY DIETRICH’S IMPRESSION OF VARIous inner moods and mysteries that inspired writer Marcellus Schiffer and composer Mischa Spoliansky to cast her in their fantastic musical revue Es Liegt in der Luft (It’s in the Air) at the Komödie Theater that spring of 1928. Set in a department store, the show was a series of twenty-four episodes about those who visit and work among an array of luxurious, useless items; most notably, it offered a series of short sketches about those who became lost in the crazy array of goods, died and remained there as wandering spirits.

Dietrich appeared in seven of the twenty-four scenes, and one of them caused a sensation. Schiffer’s wife, the tall, boyish French actress Margo Lion, was already known to be openly bisexual, and a number was prepared for her and Dietrich called “Sisters.” Ostensibly a parody of the sort of friendly girls’ duet offered by the Dolly Sisters, the song deliberately pointed to the bond between two women, happily buying underwear for one another while temporarily released from the company of their boyfriends.

Audiences and critics loved the frank but elegant sexual inferences of the number. Then, after the first week, Dietrich—protesting that their dark outfits needed a touch of color—naughtily capitalized on one of the most notorious sexual symbols of the day and pinned bunches of violets on herself and Lion. These flowers were a widely understood token, since the popular German poet Stefan Georg (and those he inspired, called the Georgists) had taken the color lavender as an emblem of homosexual love and violets as markers of its erotic expression. The play La Prisonnière by Edouard Bourdet, a compassionate assessment of modern lesbianism, had recently been successful in Paris and Berlin and one of its most daring visual motifs was violets shared by women in love. That edible flower, prized by French gourmets, also had a long Gallic association with sexual pleasure.

Each night there were several curtain calls after Dietrich and Lion strolled back and forth across the stage in an expressionless daze of mutual obsession, clasping hands and singing—Lion in a high falsetto, Dietrich in a smoky, low register that Spoliansky had found to be just right for her. “Marlene Dietrich,” reported that dean of critics, Herbert Jhering, “sings with delicacy and tired elegance. The number [“Sisters”] goes beyond anything so cultivatedly daring we’ve ever seen.”

The success of It’s in the Air led film writer and director Robert Land to Dietrich’s dressing room, where he offered her a handsome salary to appear in a romantic comedy as a Parisian courtesan famous for her lessons in lovemaking. The film was quickly produced that summer with Dietrich in the title role of Prinzessin Olala—an obvious satire of Lilian Harvey’s chaster story of Princess Tralala, who won hearts by song rather than sex. When the picture was released in September, critics took notice of Dietrich’s resemblance to another European star: “When Dietrich mimes her coquette role,” gushed the critic of Film-Kurier, “here’s another Garbo! It seems the director had all he could do to tone down her deliberate Garbo imitation.”

The reviewer was on the mark, for by this time Marlene Dietrich was well on the way to modelling herself on the mysterious and alluring Swedish actress. She had the same coloring as Garbo, and she mimicked the expression of cool diffidence that was meant to imply fires within. Dietrich had seen Garbo in several films, The Saga of Gösta Berling, The Torrent and The Temptress, which was already released in Berlin. She spoke with Mosheim and Andor (among others) of her passionate admiration. Garbo, then working in Hollywood at MGM, had quickly become one of the world’s biggest stars, and Dietrich was much taken with her remote, sphinx-like beauty.

By late summer, Dietrich was rehearsing back at the Kömodie for her role in Shaw’s Misalliance (presented as Eltern und Kinder/Parents and Children.) Windy and meandering, this is not usually rated a Shaw masterpiece: “It never stops—talk, talk, talk,” whined Dietrich (as Hypatia Tarleton), describing the Tarleton family; she might have been reviewing the play. The author’s stage directions describe Hypatia as living in “a waiting stillness, [with] boundless energy and audacity held in leash,” and from this stillness Dietrich, Garbo-like, took her cue. As a woman eager to marry only for adventure (“Who should risk marrying a man for love? I shouldn’t . . . it would make a perfect slave of you”), she played Hypatia with an almost stoic self-confidence—but the character’s sentiments were not, after all, so different from her own. Her co-star, Lili Darvas, later recalled how Dietrich made Hypatia’s independence even more arresting by speaking in a low, sultry voice, scarcely moving. “She simply sat down on the stage and smoked—very slowly and sexily—and everyone forgot the other actors were present!” Dietrich’s pose seemed so natural, her gestures so economical, that she already seemed to have the tranquil energy of a Modigliani female.

Wilhelmina Felsing after her marriage to Police Lieutenant Louis Erich Otto Dietrich.

Maria Magdalene Dietrich at the age of five (1906).

Elisabeth (left) with Maria, about 1909.

Maria Dietrich (front row, second from right, with black hair bow) at the Auguste Victoria Academy: Charlottenburg, 1914.

As a gypsy violinist in a school production, 1916.

Portrait of Maria from a family album, 1918.

Modelling in Berlin, 1922.

Flanked by two drama classmates in front of the Kammerspiele: Berlin, 1922.

Dietrich (left) as a chorus girl, dancing with the Thielscher Girls: Berlin, 1922.

On the day of her marriage to Rudolf Sieber: Berlin, May 17, 1923.

Margo Lion and Claire Waldoff.

Beginning a lifetime of entertaining on the musical saw: Vienna, 1927.

With Igo Sym (left) and Willi Forst during the filming of Café Electric: Vienna, 1927.

With Margo Lion, singing “Sisters” in Es Liegt in der Luft: Kömodie Theater, Berlin, 1928.

Publicity photo, 1928.

The last of Dietrich’s sixteen silent films: Gefahren der Brautzeit, with Willi Forst, 1929.

As an American millionairess, with Hans Albers in Zwei Krawatten: Berlin, 1929.

With director Josef von Sternberg, on the set of The Blue Angel: Berlin, December 1929.

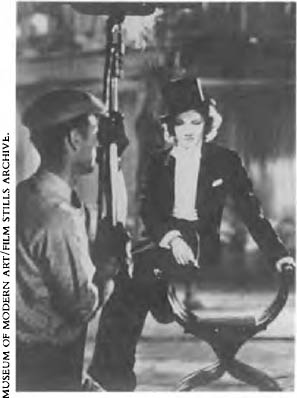

As Lola Lola in The Blue Angel.

Departing from Berlin for Hollywood: April 1930.

On the set of Morocco, 1930.

Von Sternberg at home in California, about 1930.

The critics, however, were not entertained. Alfred Kerr, Ludwig Sternaux and Franz Leppmann complained that she did too little, that she was simply showing off her lovely legs instead of any real dramatic ability—an objection again levelled at her in her next job, another Robert Land comedy—Ich Küsse ihre Hand, Madame (I Kiss Your Hand, Madame)—filmed in late 1928. In this romantic comedy she played a rich Parisian divorcée named Laurence Gérard, in love with a headwaiter who turns out to be a Russian count down on his luck. When Laurence’s overly attentive and obese lawyer (played by an actor aptly named Karl Huszar-Puffy) offers to do “anything in the world” for her, she replies, “All right, you can take my dogs for a walk.” The moment—as Dietrich scarcely glances at the hapless fellow through half-closed eyes—is both cruel and comic.

The beginning of 1929 found her still in film studios, this time in Die Frau, nach der man sich sehnt (The Woman One Longs For, released in America as Three Loves), cast as a sophisticate who is the mistress of her husband’s murderer and then falls in love with a third man, eventually getting herself killed in the bargain. Director Kurt Bernhardt (later successful in America as Curtis Bernhardt) had seen her in Misalliance and fought, against the producers, to have her play the leading role. This he later regretted, finding her difficult on two counts. First, “Marlene waged intrigues—one man against another” in life as in the story, he recalled. Exploiting the infatuation of her co-star, Fritz Kortner, she fueled petty disagreements between him and Bernhardt, the better to advance her own favor in the eyes of both. “She is an intrigante,” according to the director, who added in plain language that Dietrich “was a real bitch.”

This angry assessment was due to the second difficulty she caused Bernhardt:

She was so aware of her face that she would not let herself be photographed in profile because her nose turned up somewhat. She drove Kortner crazy (although he would have loved to go to bed with her). She never moved her head from the spotlight over the camera, facing forward and refusing to move her head to speak with other actors—she simply looked at them out of the corner of her eye. I wanted her to turn to Kortner, to be natural with him, but she wouldn’t do it. She was completely aware of the lighting and how it hit her nose. Marlene looked fantastic, but as an actress she was the punishment of God.*

Her insistence had an odd payoff, for with her austere languor and apparently affectless gaze there were more comparisons than ever to Greta Garbo. “Directors have to get her out of this Garbo mimicking!” the critic of the Berliner Tageblatt had cried on January 20, 1929 (after the first screening of her preceding film); now, the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (on May 4) said of her latest performance that she was merely “a Garbo double in her somnambulist attitude and heavy-lidded gazes—as if she were exhausted in her playful laziness.” On May 22, Variety’s Berlin correspondent concurred in virtually identical words, and at once the Berlin representatives of at least two Hollywood studios—Paramount and Universal—cabled home to report a new international star. MGM had the real Garbo; would a reasonable facsimile be acceptable? To find and engage such a copy these men were paid handsome salaries. (When the picture was finally released in America that autumn, the New York Times hailed her “rare Garboesque beauty.”)

Two more films followed in rapid succession that spring and summer. In Das Schiff der verlorenen Menschen (The Ship of Lost Men), she was an American aviatrix who is rescued by a shipful of lusty thugs when her plane goes down in the Atlantic. Guided by the French director Maurice Tourneur, Dietrich (plumply attractive even though made up to be windblown and grimy in unflattering male garb) had little to do but rouse fever among the beasts. After this—perhaps because she was still occasionally spending an evening with her old flame Willi Forst—she joined him in Gefahren der Brautzeit (Dangers of the Engagement Period), playing a sweet girl seduced by a friend of her fiancé.

In the sixteen silent films she had made in six years, Marlene Dietrich’s leading roles had been few, and these were in films that caused no great sensation. The same was true of her eleven Berlin stage appearances (and two in Vienna), so that if her name was dropped in acting circles in mid-1929, no great echo resounded.

On the other hand, despite her appearances as a calmly detached supporting player, she had a reputation among actors who knew her as a woman of untamed energies who led a tempestuous love life unfettered by her married state. Friends could not quite keep up with her romantic escapades, for she quite openly had serial (and sometimes simultaneous) liaisons with colleagues like Willi Forst and Claire Waldoff.

FROM HER NEXT ROLE, HOWEVER, WOULD COME AN association that would forever change her life and destiny as well as the history of twentieth-century film.

On September 5, 1929, a nine-scene music and dance revue called Zwei Krawatten (Two Neckties) opened at the Berliner Theater, with text by Georg Kaiser and music by Mischa Spoliansky. In this comic satire about a waiter (Hans Albers) who changes his black tie for white tie and tails (and becomes a gentleman) Dietrich was cast in the minor role of an American millionairess named Mabel who had but one line of dialogue: “May I invite you all to dine with me this evening?” Otherwise she stood with a composed but sensual allure (“plump but agile, with a smoky voice and droopy eyelids,” reported one critic).

During the first week of performances that September, there was an especially observant spectator in the audience. He was scouring Berlin’s theaters looking for a singing actress for a film he was preparing. Zwei Krawatten was a logical stop, for it featured two players he had already signed for smaller roles. On hearing Dietrich’s one line and watching her lean against the scenery “with a cold disdain for the buffoonery,” he stood up and left the auditorium—but not until he had found her name on the program. “Here was the face I had sought,” he later wrote, “and, so far as I could tell, a figure that did justice to it. Moreover, there was something else I had not sought, something that told me that my search was over.”

The director was Josef von Sternberg. Marlene Dietrich never worked again as a stage actress.

* During all this, Dietrich was rumored to be romantically linked with Igo Sym and with the actor-playwright Hans Jaray. Although there is no evidence to support the talk of these affairs, her complicated (and well-documented) love life at the height of her international fame suggests that the delicate management of simultaneous liaisons was well within her competence.

* One young flame, the architect Max Perl, later recalled that during the summer of 1929 she finally decided to correct the shape of her nose and submitted to the discomfort of cosmetic surgery; in this she was something of a hardy trailblazer, for such procedures were not the commonplace they later became.