8: 1933–1935

ON JANUARY 2, 1933, EXECUTIVES AT PARamount filed a breach of contract suit against Marlene Dietrich, asking the courts for  182,850.06—the precise amount the studio insisted they had lost since her failure to report for work on Song of Songs. Fearing her departure from the country, they also appealed to Judge Harry Holzer for an arrest warrant. This he denied, but he did issue a temporary restraining order against her employment by another studio, and he demanded her appearance in court the following week. Relaxing over the weekend with Maurice Chevalier at her Santa Monica beach house on Ocean Front Boulevard (later Pacific Coast Highway), Dietrich affected an airy unconcern worthy of Lola Lola or Shanghai Lily. Ralph Blum, her attorney, repeatedly telephoned her about the obvious professional (not to say monetary) ramifications of her recalcitrance, but she was inflexible. She would not work until von Sternberg promised to return to her for one more picture before the year was over.

182,850.06—the precise amount the studio insisted they had lost since her failure to report for work on Song of Songs. Fearing her departure from the country, they also appealed to Judge Harry Holzer for an arrest warrant. This he denied, but he did issue a temporary restraining order against her employment by another studio, and he demanded her appearance in court the following week. Relaxing over the weekend with Maurice Chevalier at her Santa Monica beach house on Ocean Front Boulevard (later Pacific Coast Highway), Dietrich affected an airy unconcern worthy of Lola Lola or Shanghai Lily. Ralph Blum, her attorney, repeatedly telephoned her about the obvious professional (not to say monetary) ramifications of her recalcitrance, but she was inflexible. She would not work until von Sternberg promised to return to her for one more picture before the year was over.

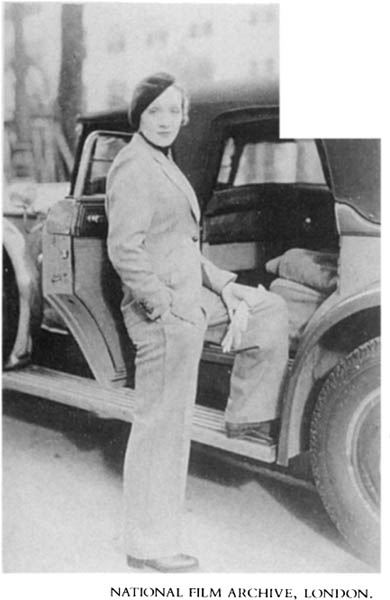

And so on January 5 her secretary, Eleanor McGeary, telephoned the studio to say Dietrich would be at Marathon Street prepared to work the following week. Paramount immediately cancelled all legal action and simultaneously offered her a new five-year contract, starting with (and ultimately advancing beyond)  4,500 per week—almost four times her original starting pay and a royal emolument in that worst year of the Great Depression. (The studio was not simply acting magnanimously. On his return from a European trip, director Ernst Lubitsch reported to Paramount that abroad the most popular movie stars were Dietrich, Garbo and Jeanette MacDonald.) This deal she wisely signed, and on January 9, wearing a man’s tweed suit, tie and beret, she joined Mamoulian for lunch in the studio commissary to discuss the first scenes of Song of Songs. “Like every German girl, I regard this as one of the great works of fiction,” she told the press. Her outfit, however (which she claimed was simply for the sake of comfort, economy and simplicity) accentuated the difference between the actress and the pious, shy peasant girl she was about to portray, and this the press gleefully noticed.

4,500 per week—almost four times her original starting pay and a royal emolument in that worst year of the Great Depression. (The studio was not simply acting magnanimously. On his return from a European trip, director Ernst Lubitsch reported to Paramount that abroad the most popular movie stars were Dietrich, Garbo and Jeanette MacDonald.) This deal she wisely signed, and on January 9, wearing a man’s tweed suit, tie and beret, she joined Mamoulian for lunch in the studio commissary to discuss the first scenes of Song of Songs. “Like every German girl, I regard this as one of the great works of fiction,” she told the press. Her outfit, however (which she claimed was simply for the sake of comfort, economy and simplicity) accentuated the difference between the actress and the pious, shy peasant girl she was about to portray, and this the press gleefully noticed.

That year, Marlene Dietrich was rarely seen in public wearing women’s clothes; in fact some said she was the best-dressed man in Hollywood. Chevalier—who objected more to her unconventional wardrobe than to the press prying around her rented beach house—demanded that she wear more traditional clothes, at least when they dined out or went dancing.

“Her adoption of trousers and wearing of tuxedos,” commented the Los Angeles Times on January 24, “[was] extreme showmanship, but on the other hand it may also prove a hit.” Her apparel was indeed widely remarked—and this greatly displeased Chevalier, who perhaps thought journalists would look for even more scabrous details if he were regularly seen with a mistress wearing only high-fashion drag. In this matter she was implacable, and the affair (but not the friendship) ceased.

The reason for the end of the Dietrich-Chevalier liaison was not simply her wardrobe, but the woman for whom she was now wearing it almost exclusively. Early in 1933, she became deeply involved in an affair with the stylish Spanish immigrant Mercedes de Acosta, a playwright, screenwriter and feminist who was also a charter member of America’s creative lesbian community.* A dominating personality in any situation, de Acosta was, as actress and writer-photographer Jean Howard described her, “a little blackbird of a woman, strange and mysterious, and to many irresistible.”

De Acosta (who was forty in 1933) moved easily in the aesthetic worlds of Eleanora Duse, Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky, and among her friends she counted at various times Mrs. Patrick Campbell, Sarah Bernhardt, Jeanne Eagels, Laurette Taylor and Helen Hayes. During and after World War I she knew well the dancer Isadora Duncan, and her own career as poet and screenwriter was firm after 1930. Although she was married to the artist Abram Poole from 1920 to 1935, the relationship was never anything but a warm friendship.

In her published memoirs, Here Lies the Heart (1960), de Acosta acknowledged that the most ardent relationships of her life were with Le Gallienne (who starred in her plays Sandro Botticelli and Jeanne d’Arc), Garbo and Dietrich, although she was indeed as busy as the notorious Natalie Barney, the doyenne of Parisian gay women. De Acosta’s accounts of her intimacies are fragrant with details not only of flower deliveries but also of candlelit evenings, long, late bedroom conversations and lovers’ quarrels. Friends who resented her frankness tried to deny the most torrid romantic revelations, often referring to her book as “Here the Heart Lies.” But there is the concomitant witness of many third parties, among them the men in Dietrich’s life; the basic truth of de Acosta’s book (if not the accuracy of every detail) is indeed unassailable.

According to the custom of that time and the requirements of law, Mercedes de Acosta employed meaningful circumlocutions: Marbury (nicknamed Granny Pop) “seemed such a man to me”; Nazimova acted “like a naughty little boy”; John Barrymore’s wife Michael Strange (an apt monicker if ever there was one) looked “like a healthy young Arab boy”; Garbo (“more beautiful than I ever dreamed she could be”) overwhelmed her so much that on first meeting her, de Acosta removed a bracelet and slipped it on her wrist. Two days later she managed to accelerate their mutual attraction.

Their common friend Salka Viertel (wife of writer-director Berthold Viertel and screenwriter of several Garbo pictures) arranged for them to meet privately in an unoccupied house near her own on Mabery Road in Santa Monica Canyon, where Garbo and de Acosta “put records on the phonograph, pushed back the rug and danced ‘Daisy, You’re Driving Me Crazy’ over and over again.” The scene ends on a closed door, behind which the relationship became more intimate (“I was moving in a dream within a dream,” de Acosta wrote tremulously).

When Garbo returned to Sweden for a holiday in 1933, Dietrich, now her rival offscreen as well as on, was quick to replace her, delivering roses and violets to de Acosta’s home—“sometimes twice a day,” the recipient recalled, “ten dozen roses or twelve dozen carnations [and] many Lalique vases.” Dietrich, grandly overstating, told de Acosta, “You are the first person here to whom I have felt drawn. I want to ask if you will let me cook for you.” She then suggested they go swimming together at the beach, and next evening the affair began. “You have exceptional skin texture that makes me think of moonlight,” de Acosta whispered as if reciting from her current screenplay assignment (Rasputin). “You should not ruin your face by putting color on it.” Thenceforth Dietrich never again wore rouge in her friend’s presence.

Mercedes de Acosta and Marlene Dietrich, almost unique among women in Hollywood, carried on their affair quite openly throughout the 1930s—despite the fact that, then as later, homosexuals were subjected to the fearful suppressions of a hypocritical movie industry. But Dietrich was not to be restricted by the norms of polite expectations any more than by the annual shifts in female fashions. With de Acosta, as with other women and men, it was often important for her to gratify someone she respected. Cooking for them, offering gifts, cleaning their homes, even doing their laundry—no gesture was too humble to demonstrate her desire to ingratiate herself and thus be included in their society. Trained by her grandmother in the arts of feminine attraction and by her mother in the crafts of domesticity, she effectively linked the Victorian model of the loyal and dutiful woman with the Prussian ideal of the tireless, attentive companion and the Berlin prototype of an unfettered, worldly maverick.

It would be tempting, in this regard, to postulate that the men in her life represented a continuing search for a father-figure, and that the women were surrogate mothers she wished to please. But human affects do not conform so tidily to the rudiments of textbook psychology. It is perhaps more accurate to argue that Marlene Dietrich was attracted to those whose styles she admired, whose intellects she respected and whose social influence she wished to share. Sex could be a useful component in a relationship—a bevel with which she could achieve emotional balance—but none of her affairs had even the temporary exclusivity that betokens a desire for loving attachment, much less permanence. Not one of her paramours, men or women, ever reported that she gave herself up to a truly grand passion; always she was remarkably self-aware and in control of the directions her relationships took.

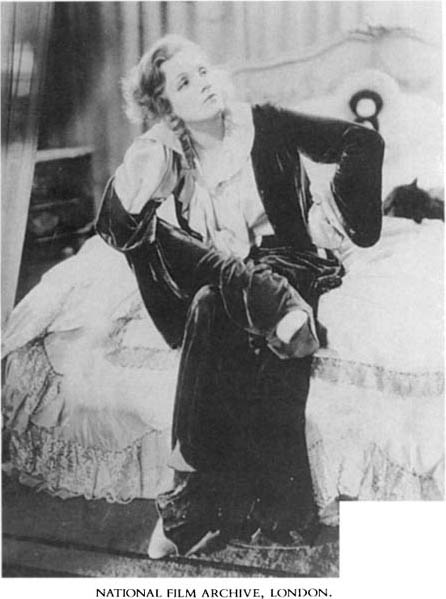

THE FILMING OF SONG OF SONGS LASTED FROM MID-January to early April, a protraction required by the almost daily arrival of new writers to tackle the script’s problems. Dietrich was cast as Lily, a devout provincial girl with an impossible ideal of romantic love, sent to Berlin after her father’s death. There she takes refuge from a boozy aunt (Alison Skipworth) in the studio of a sculptor (Brian Aherne) who convinces her to pose nude for a statue based on the faithful lover of the biblical Song of Solomon. (With more alacrity than Lily, Dietrich did model nude especially for the movie—for sculptor S. C. Scarpitta, whose statue was provocatively exploited throughout Song of Songs.) Fearing that marriage will compromise his career, the artist abandons her; and Lily’s aunt marries her off to a lecherous old baron (Lionel Atwill). Marital misery leads to accidental infidelity and the predictable descent to the demimonde before a happy reunion with the fickle sculptor.

Mamoulian remembered her as a disciplined worker but one whose performance was entirely calculated and lacking the spontaneity that derives from intuition. This may have been partly because she was working for another director for the first time and was fearful of her appearance in the picture.

Paramount makeup artist Wally Westmore recalled that Dietrich at the time was fully aware of her own special requirements—especially a key light about eight feet above her and a little to the right. “This created the hollows under the eyebrows and cheekbones which gave her that sculptured look. She never worked without that key light hitting her from above.” Dietrich continued to refer to a large mirror just off-camera to assure that this light was properly positioned for the best presentation of her face—a moment that occurred when she saw a small butterfly-shaped shadow under her nose. “If you look carefully,” Westmore pointed out, “you can see that little butterfly shadow in every movie and still picture she made.”

Cinematographer Lucien Ballard recalled that Dietrich became so skillful that she could simply lick her finger and hold it toward the key light, determining from the heat if it was exactly the proper distance from her face. As for the mirror, it was becoming a kind of totem: the reflection she saw, harbinger of the image on the screen, became her only permanent partner. Just as she was ever confident and controlling in her intimacies, so was Marlene Dietrich the epitome of the Hollywood Narcissus. Gazing at her own reflection, she became transfixed with what she saw and dedicated herself inexhaustibly to its refinement and perfection. But like the figure in the Greek myth, her self-involvement, indeed self-obsession, would lead at last to an isolating and loveless solitude. Perhaps no star was ever more trapped by her own image.

Predictably, Dietrich’s directorial tactics on the set annoyed Mamoulian, who was certainly not placated by her impolitic action each day before the first shot. “I had the sound man lower the boom mike,” she admitted years later, “and I said into it, ‘Oh, Jo—why hast thou forsaken me?’ ” Rightly, von Sternberg ignored her pleas to be present as photographic counselor—until Dietrich, on March 28, carefully but deliberately fell from her horse during a scene and, in a performance better than any she had ever given onscreen, wept for his assistance. He sped to her side and took her home, where she rested for three days. Perhaps the only memorable moment in the finished film was Dietrich’s singing of Frederick Hollander’s “Johnny,” which gave her the opportunity to convey elegant raciness even as she wandered about trying to find the right key (“We’ll disconnect the phone, and when we’re all alone, we’ll have a lot to do-o-o-o . . . I need a kiss or two—or maybe more”).*

PARAMOUNT ALLOWED HER A EUROPEAN HOLIDAY before her next assignment. Although she had spoken for almost a year of returning to Germany, she was now receiving bad press there. “One would like to see so famous a German artist show some German spirit and work in German productions,” proclaimed the Berlin trade journal Lichtbildbühne in May 1933.

It is inconsistent with our national revolution that our most famous movie star should be playing foreign roles in a foreign country under foreign directors, speaking English instead of her mother tongue. As long as she opts for the dollar and has shaken the dust of her fatherland from her feet, can the new Germany place any value on the importance of her movies?

Nazi Germany’s resentment of her was sealed when Song of Songs was submitted for German release soon after. It was, of course, banned, for it was based on a novel by a Jew, was financed by “Jewish Hollywood money” and, added the codifiers of the Licht-spielgesetz (which specified the requirements for a play or film to conform to Nazi ideology), it used a German actress to impugn the moral purity of the German people by claiming that adultery could go unpunished in their own country, where the story was set.

Still, Dietrich longed for a summer in Europe, and so with Maria—and luggage containing twenty-five suits of male clothes, dozens of men’s shirts, neckties and socks—she boarded the Europa in New York and arrived in Paris on May 19. Within hours the Parisian newspapers were detailing her shocking outfit: a chocolate-colored polo coat, a pearl grey suit, white shirt and tie—and aviator’s goggles perched saucily atop a felt hat. One Paris magistrate suggested next day that she be threatened with arrest for impersonating a man, and in fact the police seriously considered a warrant. This idea collapsed when (of all people) Maurice Chevalier told a journalist that Dietrich was a friend to all Frenchmen who loved freedom.

That week she recorded German melodies in a Paris studio and began a week’s work dubbing the French version of Song of Songs; then she, Maria, Rudi and Tamara toured France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy and the Riviera. But it was Paris most of all that she thenceforth regarded as a refuge. “I am very happy here,” she told the press. “My daughter can play in the gardens of the hotel or in the park without fear [of publicity or abduction].”

On September 26, she and Maria left Paris for New York, her garb and makeup as controversial as ever—a black and silver suit over a Chinese red blouse, matching red and black gloves and snakeskin bag, red heels on black patent pumps and her lips and fingernails painted a blazing scarlet. Hours before her departure, she was visited by German film distributors authorized to solicit her to return home to make films. But Dietrich condemned to their faces the recent dismissal from Germany of prominent intellectuals (most of them Jewish) and expressed her outrage at the May book-burnings on the Opernplatz, in which the works of Heine, Marx, Freud, Mann, Brecht and Remarque were especially targeted. Contemptuous not only of her own recent press but also of everything that the Nazis stood for, she coldly rejected their offer—as she did at least two later invitations before she sealed her loyalties by swearing American citizenship.*

WHEN MARLENE DIETRICH RETURNED TO THE States in the autumn of 1933, she was (although not a refugee) one of almost two hundred thousand Germans who settled in the United States in that decade.* Quite apart from their fierce rejection of Nazi ideology there was a subtle but well-documented self-loathing among many of these immigrants. Once champions of German culture—as Dietrich often referred to herself from 1930 to 1933—they now almost denounced their roots. Bertolt Brecht, who also settled in California, proclaimed that “everything bad in me” was of German origin, and Thomas Mann, speaking for many, lamented, “We poor Germans! We are fundamentally lonely, even when we are famous! No one really likes us.”

Marlene Dietrich could not say with any truth that she was disliked. By the same token, she seemed to exhibit the common schizoid pattern of the German émigré, rejecting her Teutonic past and refusing to conform entirely to American behavior, particularly with regard to gender roles. Simultaneously, she loved the California climate as much as her huge salary and the freedom to enjoy it—yet she complained about almost everything, and almost constantly. Hollywood was impressive in its technical efficiency; Hollywood was dreadful, and she never felt at home there. She appreciated her many American friends; she decried the informality of their lives. She enjoyed the abundance and variety of food and the opulence of restaurants; she criticized American cuisine and said she preferred to cook German-style at home. She disliked the social arrogance of many Germans in Hollywood; she dined at least once weekly at the Blue Danube restaurant, where old friends like Joe May kept the Old World alive in High German conversations. Of such contradictions was the immigrant temperament comprised before 1941—by which time American citizenship had bonded most of them forever to their adopted countrymen, whom they fervently joined against Hitler.

In October, Dietrich was back at Paramount with von Sternberg, then completing the scenario for what would be one of the most curious movies in history. First called Her Regiment of Lovers, this was a wildly imaginative account of Sophia Frederica, the Prussian princess brought to Russia in the eighteenth century by the Empress Elizabeth to marry her halfwit son Peter. Learning every political and sexual tactic of ambition and exploitation at the Russian court, Sophia—renamed Catherine (and later “the Great”)—accedes to the throne after the death of Elizabeth and the murder of Peter. Soon retitled The Scarlet Empress, the design of the production proceeded under von Sternberg’s complete control—each tiny detail of scenery, paintings, sculptures, costumes, story, photography and acting gesture. The film became, as he said, a relentless excursion into style. The credits claim the story is based on the diary of Catherine II, “arranged by Manuel Komroff”; in fact it emerged whole from von Sternberg’s most ardent inventiveness.

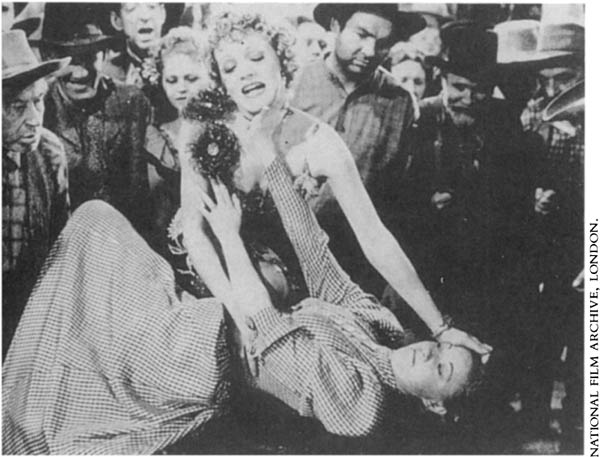

No matter that the narrative only vaguely nods at historical accuracy, the director’s goal was a presentation of something unique in the annals of film: the twisted world of nightmare, a tissue of almost pathological fantasies. Inspired by German expressionism and its use of distorted perspective to suggest mental derangement, The Scarlet Empress and its lacerating, perverse wit totter so often on the edge of satire that the appropriate response to almost every scene is problematical. Hyperbolic in design, the sets and props impede the players, Dietrich herself included (not to say the thousands of extras employed for crowd scenes), and von Sternberg’s vision emphasized an astonishing collection of brooding, expressionist statues and vast ikons that everywhere dwarf the characters. Equally grotesque were explicit scenes of torture, rape and pillage (production just preceded the application of the newly drafted Motion Picture Production Code that set standards for acceptable language and behavior for the first time in Hollywood’s history).

This florid production featured everything beyond human scale, from the vast oversize palace corridors to doorhandles twelve feet off the ground, requiring half a dozen characters to manipulate them. Amid a delirium that could have come from Edvard Munch, Dietrich as Catherine was swathed in ermine, white fox and sable, wrapped in fog and smoke, a creature looming from a demented social miasma and finally transformed into a half-mad sybarite. For the first half of the film, she had little to do but affect a wide-eyed naïveté; then, as the images of sadomasochism accumulate, she was presented as a woman whose unleashed sensuality makes her a monster of ambition (“I think I have weapons that are far more powerful than any political machine”). Amid a swirl of gargoyles with twisted bodies and images of emaciated martyrs bearing vast candelabra, no exoticism was left untried, and the picture became a procession of mobile tableaux.

As Amy Jolly in Morocco, 1930, with von Sternberg’s radiant key lighting.

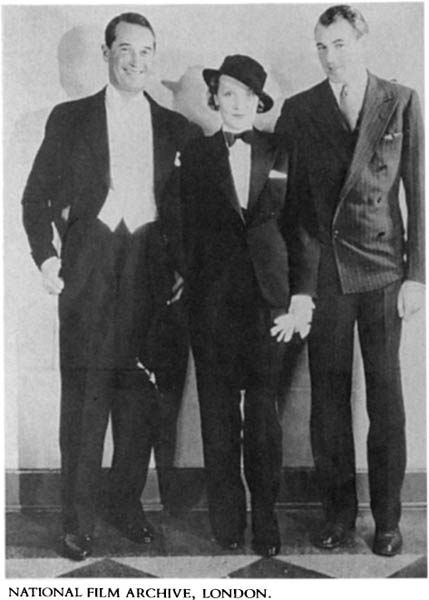

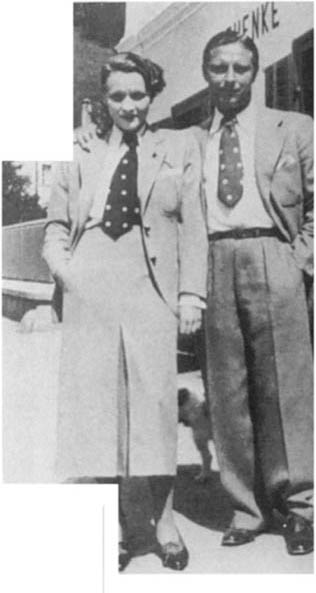

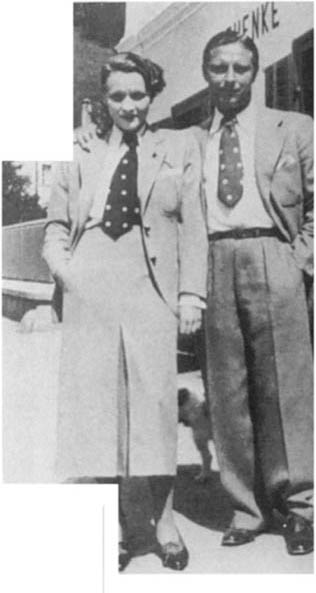

At the premiere of Morocco, with friend Dimitri Buchowetzki and Rudolf Sieber.

Exploiting a photo opportunity with Charles Chaplin in Berlin, 1931.

Filming Dishonored in 1931: an obvious rival to Garbo.

Posing on the set in 1931 as Shanghai Lily in Shanghai Express, wearing one of Travis Banton’s fantastic creations.

With her daughter, Maria, in Hollywood, 1932.

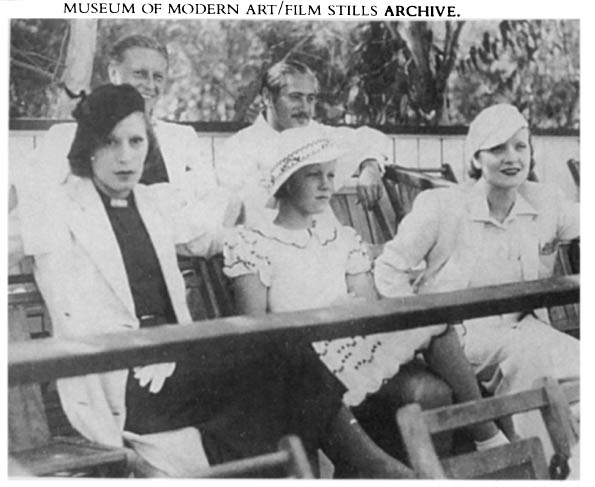

With actresses Suzy Vernon and Imperio Argentina at a Ladies’ Night in Hollywood, 1932.

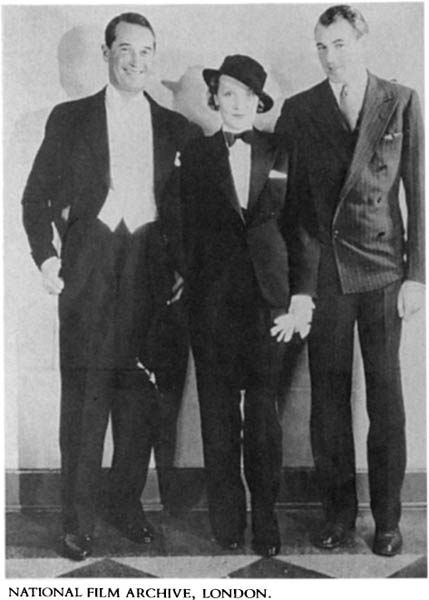

On the town with Maurice Chevalier and Gary Cooper: Hollywood, 1932.

Welcoming an ardent cadre of the Hollywood press to her home, 1933.

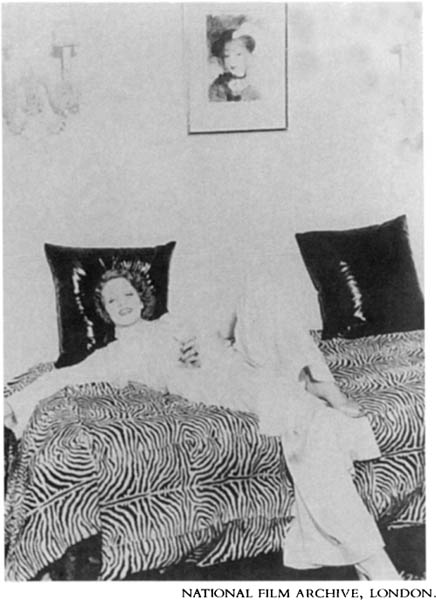

On the set of Song of Songs, 1933.

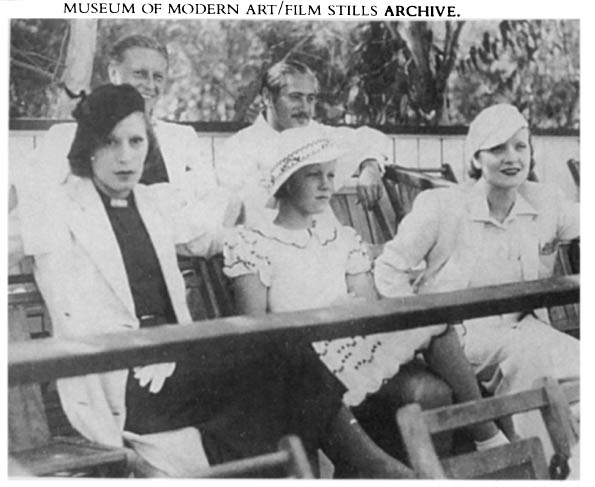

At a Hollywood polo match with Rudolf Sieber, Josef von Sternberg, Tamara Matul and Maria (1934).

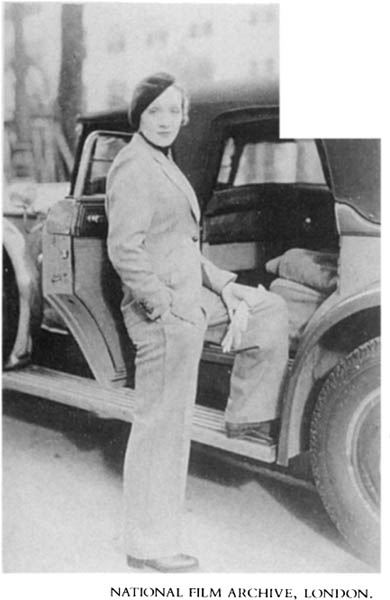

In Hollywood, 1935.

With Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., at a London theater, 1936.

With Sieber in Salzburg, 1937.

With von Sternberg and Erich Maria Remarque, at the Hotel du Cap-Eden Roc, Antibes: July 1939.

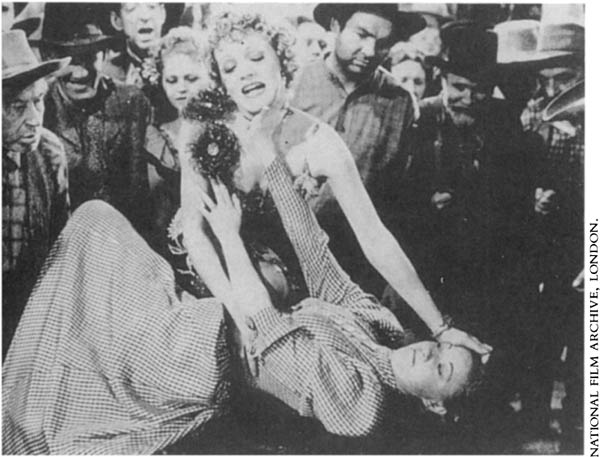

As Frenchy in Destry Rides Again, 1939.

With John Wayne in Seven Sinners, 1940.

At the Hollywood Canteen, 1943.

With Jean Gabin, 1943.

Ornate and vexatious, The Scarlet Empress was nothing like Alexander Korda’s Catherine the Great, released the same year and starring Dietrich’s old acquaintance Elisabeth Bergner; it also had none of that film’s ultimate success. So grotesque that it never bores, von Sternberg’s film is hilariously improbable in the love scenes between Dietrich and John Lodge, who played Alexei, field marshal of the Russian Army. Reasons other than his role and his performance doubtless contributed to his decision, but soon after this picture he left films and entered real-life politics, becoming in turn a congressman, governor of Connecticut and ambassador to Spain and Argentina.

Typically, von Sternberg could not dissociate his art from complex feelings about Dietrich; he was in fact drawn to this historical pageant by the situation that recurs in each of their joint pictures: a man rejected. Despotic, sometimes downright unkind and rarely popular with his cast, von Sternberg was more and more frequently described as a dictator on his pictures. In this regard, he painstakingly directed Sam Jaffe in the role of Grand Duke Peter, who emerges as nothing so much as a stencil of the director himself, a smiling, mad dwarf commanding his toy soldiers round a “war set,” an idiot fated to abandonment by a woman whose beauty renders him helpless. Otherwise, The Scarlet Empress is notable only for the casting of Maria in a brief, early scene as the young Sophia.

When Dietrich returned from Europe, von Sternberg was unsure of their relationship; she spent much of her nonworking time with Mercedes de Acosta and a new circle of acquaintances in Brentwood and Santa Monica—amusing and talented companions like Martin Kosleck and his lover Hans von Twardowsky, German actors who were able to work occasionally in Hollywood films. Feeling distant from her, von Sternberg more than ever played the directorial tyrant at the studio, imprudently expressing his fear of separation by asking her to repeat difficult scenes, as if she would thus realize a kind of pathetic dependence on him. Predictably, this had the contrary effect: the more he tried to psychologically apprehend her, the more she politely withdrew—but never revealed her dismay at work. John Engstead recalled that von Sternberg required her to descend a vast staircase in her elaborate costume forty-five times; she obeyed without a single complaint. “They say von Sternberg is ruining me,” she said with apparent innocence to a journalist. “I say let him ruin me. I would rather have a small part in one of his good pictures than a big part in a bad one made by someone else.”

Her director was not, of course, ruining his star at all, nor did anyone seriously wager that the brightness of her publicity could be long dimmed by the fiasco of The Scarlet Empress. But there was a new and deep strain between them after filming completed in early 1934. It would be hard not to link some of the disconnection to the influence of Mercedes de Acosta and her friends, for by this time Dietrich was becoming more and more blunt in pursuing actresses she found attractive; among them were Paramount’s Carole Lombard and Frances Dee, whose unregenerate heterosexuality did not dissuade Dietrich from her usual stratagems of flower deliveries and romantic blandishments. Lombard, a beautiful, brash blonde, was unamused: “If you want something,” she told Dietrich after finding one too many sweet notes and posies in her dressing room at Paramount, “you come on down when I’m there. I’m not going to chase you.” As for Dee (who had been directed by von Sternberg in An American Tragedy) she and her husband Joel McCrea recalled Dietrich’s inordinate attentions, asking von Sternberg to treat Dee with especial care because (so said McCrea) Dietrich was in love with her—but in love, as with Lombard, to no avail.

In addition, Dietrich did not please von Sternberg (or Mercedes, for that matter) by attaching herself to John Gilbert, then thirty-eight, whose alcoholism had rendered him virtually unemployable as a film actor. “He was killing himself,” according to his daughter, “and she would not have it. Marlene simply took over.”

Applying every tactic of affirmation and encouragement, Dietrich persuaded Gilbert to seek medical help to stop drinking. She asked him to escort her to parties, movie premieres and art galleries; she drove him to the beach, to restaurants and to concerts. Hovering about with maternal concern, she steered him away from liquor, offering (in the felicitous term of playwright Robert Anderson) tea and sympathy—and of course herself. According to every account, her actions were benevolent; yet it was certainly not irrelevant that Gilbert was still a close friend of Greta Garbo’s, who had once briefly been his lover and who also tried to help him. In a way, then, Gilbert, like de Acosta, was a link to the enduring rival Garbo, one whom Dietrich must appropriate unto herself.

The year was in fact busy with new friendships. In March, returning aboard the Ile de France from a one-week sojourn in Paris, she met Ernest Hemingway, whose fame made him as attractive to her as his burly macho affectations. The circumstances of their introduction were brilliantly Dietrichian. Entering the ship’s dining room in a long, white, tightly beaded gown, she approached a table adjacent to Hemingway’s but then she counted twelve guests already seated. Hesitating to be the unlucky thirteenth, she started to move away—whereupon Hemingway (as she may have expected) gallantly leaped forward to be the fourteenth at her table. She suggested instead a stroll round the decks.

At once Dietrich took him as something of a counselor and father-figure, calling him (as did others) her “Papa.” She was most of all one of his buddies, and in this regard the relationship was perhaps unique in his life. By a kind of tacit common consent, they were never lovers—a situation that might have aborted friendship with this man who simultaneously revered and feared women. His domineering mother, frequently dressing him as a little girl, certainly helped prepare a lifelong pattern of sexual confusion, and his subsequent relations with women always bore the twin hues of fierce resentment and fantastic idealization. His “loveliest dreams,” as he said, were often of Dietrich, who was “awfully nice in dreams”—a sentiment worthy of von Sternberg. With Dietrich, Hemingway could simultaneously enjoy the nurturing adulation of a beautiful and famous woman and the matey fellowship of someone who never threatened him by demanding sex; in this way, Marlene Dietrich was the ideal Hemingway heroine. He called her The Kraut.

Their correspondence flourished over the next twenty-five years, Hemingway retaining about two dozen of her letters, and she preserving his in a vault. Mostly they concerned shifts in her career, for Dietrich often turned to him for advice. “I never ask Ernest for advice as such but he is always there to talk to, to get letters from,” she once said, “and I find the things I can use for whatever problems I may have.” Uncertain over whether to accept a certain job, she received terse advice: “Don’t do what you sincerely don’t want to do. Never confuse movement with action.” In those last five words, she said, “he gave me a whole philosophy.” For her part, she countered by trying to introduce him to astrology, which in 1934 had recently struck her fancy and which would often occupy her for the next five decades. This he rejected, however, saying (probably unaware of the double meaning) that he did not want his life “run by the stars.”

Nor, it seems, did Josef von Sternberg. The commercial failure of The Scarlet Empress conspired with his own gradual but ineluctable distance from Marlene Dietrich, and that autumn of 1934 he and Paramount’s executives discussed terminating the six-year collaboration between them. To his relief, she agreed that they would part company after one final picture he was preparing. “She is a complete artist,” he told the press, “and another director will be better for her now. We have gone as far as we can together, and now there is the inevitable mold or groove that is dangerous for us both.” For the time being, he had nothing more to say, and Dietrich herself was silent.

BY AUTUMN 1934, B. P. SCHULBERG HAD LEFT Paramount and was succeeded as production chief by director Ernst Lubitsch. In 1920, the studio had realized considerable success with a silent film version of Pierre Louÿs’s novel La Femme et le Pantin (The Woman and the Puppet), and to this literary source von Sternberg turned as the basis for a new picture he intended as a Spanish fancy—indeed, he wanted to title it Caprice Espagnole (after the musical theme to be inserted into the film). But Lubitsch, after reading the outline and first draft prepared by von Sternberg and John Dos Passos, decided on the more provocative designation The Devil Is a Woman. The narrative concerns a cigarette-factory tart named Concha Perez (Dietrich) who seduces, ridicules and finally destroys a middle-aged officer of the Civil Guard (Lionel Atwill). He tries to dissuade a younger man (Cesar Romero) from dallying with “the most dangerous woman you’ll ever meet,” and their rivalry over her leads to a duel in which the older man allows himself to be wounded. Although Concha at first seems on the verge of leaving for Paris with the younger man, she returns to the muddled affair with the injured, bereft officer, a man virtually diseased by his own fatal passion for a devil of a woman.

In its final form, of course, the picture harmonized closely with the contours of von Sternberg’s own tangled affective life. And so, after the veiled and historicized presentation of his star as an ambitious empress with a regiment of lovers, von Sternberg began what would be the most personal, most dazzlingly exquisite of their films—“because I was most beautiful in that,” Dietrich said bluntly. (Since he had at last been formally admitted to membership in the American Society of Cinematographers, the director proudly thus affiliated himself with this craft union in the credits of the finished film—“directed and photographed by Josef von Sternberg, A.S.C.”)

The recognizable, usually mundane and often tawdry settings of The Blue Angel, Morocco, Dishonored and Blonde Venus had borne the stamp of expressionist flamboyance in The Scarlet Empress: here, however, every visual detail is drenched in the hyperbole of madcap carnival, hysterical with the atmosphere of a romantically daffy jubilee. The picture opens with a six-minute scene of carnival revelry in Spain, circa 1890, amid a dizzy, serpentine panoply of confetti and ultrachic costumes. And then there is an odd reprisal of the situation in Rouben Mamoulian’s Song of Songs, as if von Sternberg wished to appropriate that picture for himself by creating a narrative with the same players. Just as in the earlier film, von Sternberg’s surrogate (Lionel Atwill, made up and lit almost as a twin, complete with moustache) buys Marlene Dietrich from Alison Skipworth.

“I told her mother that I loved Concha,” he says to Romero in words that precisely echo the relationship between director and actress, “and although there were certain ties I could not form [that is, marriage], I wished to provide for her, take charge of her education, in other words make myself her protector.”

Concha was never, to the dismay of the officer, a faithful, loving companion, and when he finally confronts her treachery—“You’re not going to play with me anymore!”—she screams: “This is superb! He threatens me! What right have you to tell me what to do? Are you my father? No! Are you my husband? No! Are you my lover? No! Well, I must say you’re content with very little!” To which he cries, “Am I?” and lunges at her, attacking and nearly strangling her. An uneasy reconciliation scene is later followed by his suggestion, “Let’s leave this miserable place,” and her reply, “But I can’t—my contract!”

“That woman has ice where others have a heart. She wrecked my life—there were others as well,” Atwill tells Romero. (In Blonde Venus, it is said of Dietrich’s character, “She’s the proverbial iceberg who used one man after another.”) The inevitable destroyer Lola Lola has now come full circle, and all the intervening variations of the tarnished woman come together in Concha Perez.

Never had the dialogue of a Dietrich-von Sternberg film so clearly matched real life, or so closely resembled von Sternberg’s ultimate resentment of the fact that their relationship had not been one of Marlene the puppet and Jo the manipulator. It had, in fact, been the reverse in von Sternberg’s perception, she had been the cruel woman—la femme et le pantin—toying with her plaything. (The inspiration for the image is a small painting by Goya in the Prado, of four girls tossing a male puppet into the air.) The fickle woman of the film finally drains her protector of life, and just as before with Menjou/von Sternberg in Morocco, so for Atwill/von Sternberg here: to love Dietrich is to be condemned to a fatal melancholy.

Five years later, the man’s passion is beyond patience, expressed only through humiliation and rage. The Devil Is a Woman is in every sense the most moving portrait von Sternberg offered of his perceptions of his sometime mistress—here an intelligent and sensitive man is helpless to free himself from the narcotic effect of her allure, ever tragically aware of what is happening to him as he pursues a woman who will never give him anything to compensate for what he is losing.

As might have been expected, there were tensions during filming. “Von Sternberg made everyone’s life miserable,” recalled Cesar Romero years later,

but he was especially mean to Dietrich. He bawled her out in front of everyone, made her repeat difficult scenes endlessly and needlessly until she just cried and cried.

“Do it again!” he shouted. “Faster! . . . Slower! . . .” Well, he had been mad about her, after all, and now that their relationship was ending he took it out on her and everybody else.

Nevertheless, Dietrich remained, publicly, the consummate professional, obeying each command and agonizing over every detail of her role, wardrobe and makeup. John Engstead remembered that Paramount’s wardrobe chief Travis Banton designed an elaborate Spanish comb for her, and hairdresser Nellie Manley fashioned braids from Dietrich’s own locks, wiring these to the comb. Each evening, Manley snipped the bands and released the comb with heavy wire cutters as Dietrich fell forward, arms and head resting on her dressing table, tears streaming down her face, exhausted from the pain of this intricate device.

Soon studio accountants were in anguish, too. Not only was the film a resounding critical and commercial failure in its American release, but there was virtually no foreign exhibition. This was due to a curious intervention by the Spanish government, which objected to the portrayal of an official mocked by an immoral woman. On October 31, 1935 , Gil Robles (Spain’s war minister) announced that henceforth all Paramount films would be banned in Spain unless The Devil Is a Woman were withdrawn at once from worldwide circulation. By November 12, the U.S. State Department entered the fray, ordering Paramount to recall and destroy all prints of the picture, which the Spanish ambassador had called “an insult to Spain and the Spaniards,” and to burn the negative (happily, it was not destroyed; it simply “disappeared” for forty years). At the time, it was rumored that a commercial treaty then being drafted between America and Spain effected the studio’s quick capitulation, which amounted to little more than blackmail, but the truth was even more reprehensible. A wealthy Spanish industrialist loyal to Franco had promised to back the foundation of a major film studio in Madrid if he could be guaranteed minimum foreign competition. A quiet, quick series of diplomatic maneuvers answered his request.*

BY MARCH 1935, THE COLLABORATION WAS History. But unlike their proxies at the end of The Devil Is a Woman, the von Sternberg-Dietrich collaboration ended not because she walked out on her man but because in real life he walked out on her. “I am no longer Mr. von Sternberg’s protégée,” Dietrich told the press that month in an astonishingly pointed revelation.

It is Mr. von Sternberg’s own wish that we should be separated professionally—not my wish. I would prefer to go on as in the past. It is so wonderful to have someone look after your interests. He wants a rest, and he feels that this is the time for me to go my way alone. At all times he has been very courageous. He prefers to create pictures as he feels, and it is not I who wished this association to be broken, but he.

“He dreaded the day I would become a star,” she wrote more candidly after his death,

for he loved the creature whose image was reflected on film. Before von Sternberg took me in hand, I was no one . . . The films he made with me speak for themselves. Nothing to come could surpass them. Filmmakers are forever doomed to imitate them.

That spring, Paramount negotiated a new contract with Dietrich’s agent, Harry Edington, which guaranteed her a total salary of  250,000 for two pictures over the next year, with the right to approve story and director; it was the most lucrative contract in Hollywood history, and it marked the beginning of an entirely new phase of her career and her fame. It was also a triumph of negotiation, for although Edington knew as well as anyone that Dietrich’s popularity was in severe decline, he persuaded Paramount that separation from von Sternberg would reverse all that; Edington added that after all they still required a glamorous European à la Garbo. (“My salary is not large if you consider it is spread over a year,” said Dietrich without irony. “To rent a house with tennis court and swimming pool, I must pay at least

250,000 for two pictures over the next year, with the right to approve story and director; it was the most lucrative contract in Hollywood history, and it marked the beginning of an entirely new phase of her career and her fame. It was also a triumph of negotiation, for although Edington knew as well as anyone that Dietrich’s popularity was in severe decline, he persuaded Paramount that separation from von Sternberg would reverse all that; Edington added that after all they still required a glamorous European à la Garbo. (“My salary is not large if you consider it is spread over a year,” said Dietrich without irony. “To rent a house with tennis court and swimming pool, I must pay at least  500 a month.” Few were inclined to offer much sympathy, especially after she leased a richly appointed home in Bel-Air, an enclave of lavish estates west of Beverly Hills.)

500 a month.” Few were inclined to offer much sympathy, especially after she leased a richly appointed home in Bel-Air, an enclave of lavish estates west of Beverly Hills.)

“I AM MISS DIETRICH, MISS DIETRICH IS ME,” Josef von Sternberg had said. Now at last, with each fantasy revealed—from provocation to passion to revenge—the relationship had run its course. In their art, she was the triumphant character, but in the end the artist had to act in his own interest, and so he paid “a final tribute to the lady I had seen lean against the wings of a Berlin stage,” and then he quietly withdrew.

In every one of their films, an older man had been displaced or replaced in the affections of her character; consecutively, they had been played by Emil Jannings, Adolphe Menjou, Warner Oland, Herbert Marshall, Lionel Atwill, Sam Jaffe and again Lionel Atwill. Just so in real life now, for with much Hollywood hoopla and a lucrative new contract Dietrich not only survived but went on to conquer.

As for Josef von Sternberg, he left both her and Paramount, wandering from studio to project and completing only seven films over the next thirty-four years; none of them was successful, none had the emotional wholeness of the preceding septet. In a way, he was both Pygmalion and Galatea, the ultimate victim of precisely the mythical creature he had created and promulgated. Restricted and made subordinate by his own fancies, he could really only celebrate her beguilement of him. And Dietrich was both enchanter and enchanted, too—thus also a victim of her own poignant need to please, of her ambition and her longing for professional security, of her dependence on a man she had (without malice) exploited.

After the favorable reactions to The Blue Angel and Morocco, American audiences continued to find her exotic and alluring, but even they gradually agreed with critics that visual splendor alone was unsatisfying. Sometimes, to be sure, Marlene Dietrich was photographed so magnificently that she seemed to be acting, but that, too, was mostly an illusion. Forever after, the autocratic, benighted lover and his obedient, heedless beloved never spoke of the wounded passion, the shared, secret history behind these seven confessional works, incomparable in the history of film.

182,850.06—the precise amount the studio insisted they had lost since her failure to report for work on Song of Songs. Fearing her departure from the country, they also appealed to Judge Harry Holzer for an arrest warrant. This he denied, but he did issue a temporary restraining order against her employment by another studio, and he demanded her appearance in court the following week. Relaxing over the weekend with Maurice Chevalier at her Santa Monica beach house on Ocean Front Boulevard (later Pacific Coast Highway), Dietrich affected an airy unconcern worthy of Lola Lola or Shanghai Lily. Ralph Blum, her attorney, repeatedly telephoned her about the obvious professional (not to say monetary) ramifications of her recalcitrance, but she was inflexible. She would not work until von Sternberg promised to return to her for one more picture before the year was over.

182,850.06—the precise amount the studio insisted they had lost since her failure to report for work on Song of Songs. Fearing her departure from the country, they also appealed to Judge Harry Holzer for an arrest warrant. This he denied, but he did issue a temporary restraining order against her employment by another studio, and he demanded her appearance in court the following week. Relaxing over the weekend with Maurice Chevalier at her Santa Monica beach house on Ocean Front Boulevard (later Pacific Coast Highway), Dietrich affected an airy unconcern worthy of Lola Lola or Shanghai Lily. Ralph Blum, her attorney, repeatedly telephoned her about the obvious professional (not to say monetary) ramifications of her recalcitrance, but she was inflexible. She would not work until von Sternberg promised to return to her for one more picture before the year was over.