16: 1957–1960

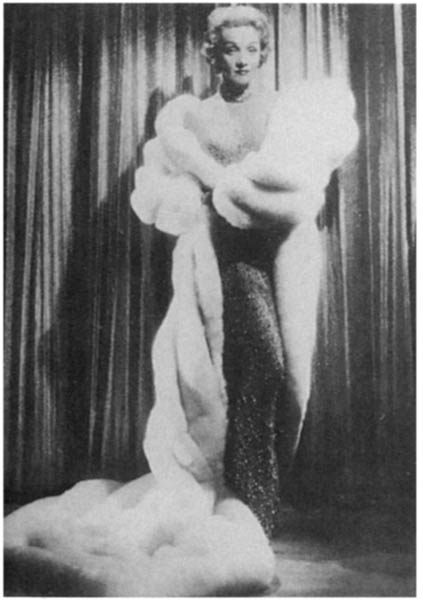

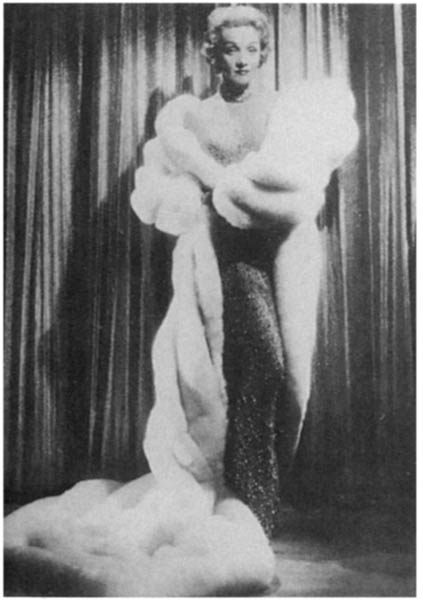

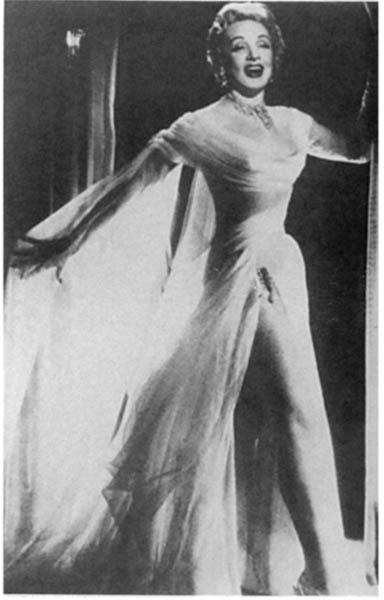

ON FEBRUARY 14, 1957, SIX WEEKS AFTER her fifty-fifth birthday, Marlene Dietrich opened her annual Las Vegas engagement, this time at the Sands Hotel. She began her midnight act with a husky, almost bleated rendition of “Look Me Over Closely”—an apt tune in light of her outfit, a floor-length, skintight gown with thousands of tiny handsewn beads and a white, twelve-by-eight-foot wrap fashioned from five million swan feathers (which weighed less than four pounds). Dietrich had undergone yet another face-lift earlier that winter, and with expert makeup and a hairpiece designed to her meticulous specifications, there was inevitably something too studied, too exaggeratedly artful about her appearance. At odd moments when she regarded herself in a mirror, she saw (as she told photographer John Engstead) a grotesque female impersonator. One evening backstage in Las Vegas, a seam split, several dozen dress-beads clattered to the floor, and she was anxious that all of them might fall off and scatter. She could have seen the moment as metaphoric, a marker of the unravelling of that part of herself that was entirely false.

Yet to the maintenance of this fundamentally unreal personality, of a strictly created and annually recreated illusion, she dedicated herself with canny zealotry. Her avidity for this was based on a fierce professionalism and a tenacious will to succeed, but she was also imprisoned within a persona for which there was simply no replacement: in thirty years there had been only minor variations to her image as a femme fatale.

Although Marlene Dietrich was associated with a kind of enduring, timeless beauty and the triumph of wily, feminine allure, it was equally clear from her image (as from her life) that much of her victory was Pyrrhic, that it had left her with fame and a bank account, social access anywhere, and an often unacknowledged loneliness everywhere. She told many people some facts of her life, but no one was privy to her deepest feelings; indeed, many who knew her well (her publicist Rupert Allen, for one) felt that perhaps she had no deep feelings at all, that by middle age she had successfully inured herself against grief, loss and the demands of authentic love—that there was, in other words, no frame of reference outside herself.

In any case, there certainly seems to have been no one in whom she ever confided in a deeply affectionate way. Neither lovers nor platonic friends like Noël Coward (whose gift for true camaraderie has been much documented) ever described her with any of the empathy that characterizes mature friendship. Dietrich was thus, perhaps unwittingly, severely limited by her devotion to an exhausted, manufactured personality to which she had no alternative because she considered no choices.*

Some of this was perhaps inevitable for a woman who had not acted on the stage since 1929, and whose international fame depended on an audience’s familiarity with how she had once looked; she was, in other words, something of a museum piece. But actresses were presented very differently in 1957 from the way they had been in the 1930s—and not only in hemlines, cosmetics and lighting. Of those women who had made films in the 1930s, few had careers that survived into the new world of movie entertainment, threatened by television, but saved by Technicolor, wide screens and gradually more latitude in content and treatment. The public now preferred the fey charm of Audrey Hepburn, the sheer luxuriance of Marilyn Monroe, the sensuous youth of Elizabeth Taylor, the perky audacity of Shirley MacLaine and the muted passion of Deborah Kerr. Dietrich had only a past iconography to tap, and only a present reputation for appearing on the lists of Best Dressed Women: she gave no indication of having grown into a new era or a fresh perception. It was of course fine to be the carrier of a grand history, but there was a consequent danger, and Dietrich seemed in a strange way mummified. In that regard, she was victimized by one of the most fantastic aberrations in contemporary culture, one to which she herself contributed: the futile quest for perpetual youth and the concomitant obsession with forestalling death.

AT THE CONCLUSION OF HER LAS VEGAS ASSIGNment, Dietrich hastened to Los Angeles, where in 1957 she appeared in two of her last four film roles. For Orson Welles, the star and director of Touch of Evil, she agreed—on two days’ notice—to work one afternoon and evening, impersonating a cigar-chomping, fortune-telling bordello madam. “There was no talk about reading the script or what the part was at all,” according to Welles. “She said, ‘What should I look like?’ I said, ‘You should be dark.’ ” And that gave Dietrich her clue: tearing through cartons of her own costume remnants and scouring thrift shops, she came up with a stringy black wig, spangled shoes and a variety of tacky odds and ends that were perfect for the role and delighted her old friend the director.

Appearing in three scenes of Touch of Evil for a total of less than four minutes, Dietrich—perilously close to unintentional parody—advised the pathetic, vicious character played by the obese Welles to “lay off the candy bars,” and then sadly informed him, “You have no future—it’s all used up.” For the rest of her life, she often said this brief role was “the best thing I have ever done in films . . . I think I never said a line as well as the last line in that movie, ‘What does it matter what you say about people?’ ”

In June, Dietrich received an urgent cable from the writer and director Preston Sturges, then residing in Paris, asking her to replace Ingrid Bergman in the French production of Robert Anderson’s play Tea and Sympathy so that Bergman could appear in a Sturges production. But she could not, for she had accepted Billy Wilder’s offer to play the apparently duplicitous but actually faithful wife who is the Witness for the Prosecution.

In this screen adaptation of the successful play, Dietrich was Christine Vole, a former cabaret star brought from Germany to England after the war by her husband (Tyrone Power). He is accused of murdering a wealthy widow, and during a complicated trial she schemes to prove that she is untrustworthy as a witness against him. Her ploy works, and the jury pronounces her husband innocent, framed by his faithless wife; but once he is free, she reveals to his attorney (Charles Laughton) that her husband was indeed guilty of the crime, and that she has risked everything and perjured herself to free him. Greeting her husband after his release, she then learns that he is eagerly awaited by another woman; scorned, she stabs him to death, immediately earning the advocacy of the same attorney.

As a woman who plots, lies and kills for love, Dietrich put aside every bangle and bauble of her nightclub image and worked to exhaustion on a role that could have been written for her. “She was like nothing I’ve ever seen,” according to Billy Wilder. “Marlene was always a worker, always the good trouper, but on this picture she was tireless—it almost seemed as if she thought her career depended on it.” She worked daily with Wilder and into the evenings with Laughton to perfect the cockney accent she needed for her disguised character-within-the-role.

Seconds before her entrance, Laughton warns a colleague about her character: “Bear in mind she’s a foreigner, so be prepared for hysterics or even a fainting spell. Have smelling salts ready.” At once her voice is heard off-camera: “I don’t think that will be necessary.” Only then do we see her, framed in a doorway, a somewhat remote figure in a tailored suit, cloche hat and gloves. In utter simplicity, photographed full-face in black and white, Dietrich appears as nothing like a screen goddess; her beauty is in fact severe. “I never faint, because I’m not sure that I will fall gracefully,” she says unblinkingly to Laughton, “and I never use smelling salts because they puff up the eyes.” Alert with pretense and passion, her mouth defiant, Dietrich’s Christine was from the first moment a woman of steely self-confidence—a fascinating role played without fussy technique.

There was one concession to the legend, however—an early flashback devised for the film so that Dietrich could belt out “I May Never Go Home Anymore” at a German cabaret called The Red Devil, a neat inversion of her most famous venue. For this sequence, as homage to moments in several earlier movies, Dietrich causes a riot, soldiers rush the stage and her trouser leg is conveniently torn; it was the last glimpse, in film history, of this Prussian cheesecake.

“It is not easy to teach Cockney to a German glamour-puss who can’t pronounce her Rs, but she did astonishingly well,” noted Noël Coward in his diary on August 4 after visiting Los Angeles and adding his own suggestions to Laughton’s diction lessons. As she worked on her accent and created garish makeup for the scene in which Christine disguises herself, Dietrich had the idea that her performance might win her what she thought was a long overdue Academy Award. She had been nominated only once (for Morocco). “She was desperately disappointed when she was not even nominated for the award,” according to Billy Wilder. And the veteran Hollywood reporter Radie Harris remembered “too well how much [Dietrich] wanted an Oscar. She even went so far as to call me from Las Vegas and asked me to please hint in my column that she deserved [it].”* Dietrich also complained to Rupert Allen that the publicists engaged for Witness for the Prosecution were not giving her the attention she merited, nor advancing her for the Oscar sufficiently. But none of her self-promotion availed.

During production she and Wilder were, as always, the best of friends. He and his wife included Dietrich at a dinner party that season, and years later he recalled

that of course Marlene was the center of attention. I began a kind of little interview, urging her to tell us all the story of her fantastic life. I asked her who was the first man in her life and she said her violin teacher. She was holding back nothing, and everyone was hanging on her words. Next I said, “Now tell us about your relations with women,” and she began, “Well, of course there was Claire Waldoff, and then . . .” By this time there was a great silence in the room, and I turned to everyone and asked, “Oh! Are we boring you?”*

That autumn she was back in New York, theatergoing with Noël Coward and offering companionship to playwright Robert Anderson, whose wife had recently died. (They had met briefly when Maria had appeared in a road company production of Tea and Sympathy.) “I understand you’re lonely,” she announced on the telephone to him one day, inviting him to escort her to a play next evening. This Anderson declined, as he did any contact more intimate than a luncheon, for he did not wish to accept Dietrich’s overture.

But it was really she herself who was lonely, and in the following year she embarked on a series of short trips round the country, attempting to visit almost anyone she knew on a first-name basis, as if she felt her span of life was quickly running out. In 1958 and 1959 she performed her annual Las Vegas engagements (now worth  40,000 a week for four weeks), and few in her audiences seemed to care that there was less voice than ever. Everything about her appearances, in fact, seemed more and more frozen, stylized. Her shows were expanded in those years to include concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Sâo Paolo, Buenos Aires and Paris, where she added to her repertory American ballads (“My Blue Heaven,” for example), recent show tunes (“I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” from My Fair Lady), and German, French and Brazilian standards.

40,000 a week for four weeks), and few in her audiences seemed to care that there was less voice than ever. Everything about her appearances, in fact, seemed more and more frozen, stylized. Her shows were expanded in those years to include concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Sâo Paolo, Buenos Aires and Paris, where she added to her repertory American ballads (“My Blue Heaven,” for example), recent show tunes (“I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” from My Fair Lady), and German, French and Brazilian standards.

“She looks ravishing and tears the place up,” Coward noted in Paris after her show at the Théâtre de l’Etoile in December 1959, “[but] she has developed a hard, brassy assurance and she belts out every song harshly and without finesse. All her aloof, almost lazy glamour has been overlaid by a noisy, ‘take-this-and-like-it’ method which, to me, is disastrous. However, the public loved it.”

COWARD WAS ON THE MARK, FOR DIETRICH’S SHOWS (preserved on recordings) were unvarying presentations of the same songs, each introduced by her embellished, self-aggrandizing anecdotes about (a) auditioning for The Blue Angel; (b) coming to America; (c) making this or that film; (d) serving the troops in wartime. And on each recording the audience’s applause was of course carefully and completely preserved. With Dietrich supervising the final cuts, it was also at least partly created: it was easy for her to demand (and subsequently easy for the listener to discern) the looped repetition of cycles of applause, whistles, shouts of approval. Reporters (like friends) were frequently subjected to documentations of this applause: “She plugged in a tape recorder and played me ten minutes of the uninterrupted applause which greeted her act when she was in Rio,” according to a journalist from London’s Sunday Express, “and I knew as soon as she discovered that my breathing was regular and my pupils undilated that there was no hope [that she would like or approve me].”*

As for her singing, it could hardly be called that. Nor was she properly a diseuse in the style of Edith Piaf or Lotte Lenya, for there was something chillingly detached and unemotional about almost everything Dietrich recorded; it was hard to believe that she was wounded by love, impossible to accept from her the lyrics about emotional devastation. She did not, in other words, communicate so much the sense of a song’s lyrics as she marketed herself, and the recordings have none of the vitality or animation of those she did for films in the 1930s. Dietrich gave no indication that her heart had expanded as the voice contracted. “Let’s not fool anyone,” she admitted in 1959. “It takes money to be glamorous these days. Glamour is what I sell in my act, and it costs plenty. It’s my stock in trade. My clothes arouse more comment than anything except maybe my figure.”

She marketed herself otherwise, too, recording five-minute network radio spots of advice in 1958 and 1959 that were astonishingly vapid even according to the stricter, more conventional requirements of talk-radio at the time:

—“It is very difficult to be happy without working, without taking pride in achievement, however small.”

—“Know your own limitations and be realistic about them. If you are a good carpenter, take pride in being a good carpenter.”

—“Men are so easy to love. All women have to do is to orbit around them, to make them the center, the hard core of existence. The trouble with so many modern women is that they want the men to orbit around them.”

—“Teenagers must be patient, more tolerant of our failures. We have some love and wisdom to give, and of course we all have to maintain our sense of humor.”

A sense of humor failed her one night in 1958, however, when she attended Carol Channing’s act at the Tropicana Hotel in Las Vegas. In a diaphanous negligée, mesh hose and exaggerated German accent, Channing devastated her nightclub audience with a parody of the queen of glamour, lying on the floor with her legs pointing to the ceiling and, à la Dietrich, chattering endlessly about herself—her songs, her films, her wardrobe, her travels, her wartime service. Then came her punchline: “But enuff about me—let’s talk about you for a vile,” she muttered throatily. “Vot do you tink of my outfit? Is it too flimsy for a grandmother?” The spotlight located Dietrich at a table as she rose magisterially and swept out. The impersonation remained in Channing’s act for several years despite Dietrich’s request that it be dropped.

PERHAPS RARELY HAS MERE CELEBRITY SO SUCCESSfully sustained itself as in the case of Marlene Dietrich. “I don’t ask whom you are applauding—the legend, the performer or me,” she told an audience at the Museum of Modern Art after a retrospective tribute in April 1959. “I personally liked the legend. Not that it was easy to live with, but I liked it.” Tens of thousands agreed with her in the coming decade.

Everywhere, she knew how to exploit that legend. In Rio (part of a three-city South American tour in August 1959) a vast throng gathered to greet her arrival at the theater and she apparently swooned. “I didn’t really faint,” she later admitted, “but it was the only way I could get inside. Besides, there were many photographers present, and it was a good chance for publicity.” But as Rupert Allen later verified, many in the pressing crowd were paid, professional theatrical extras glad to be part of a documented mob scene. They were present after she stormed into the local constabulary and demanded that off-duty police attend her that evening.

Just so in Paris, where the following December she planned every detail of her arrival: Maurice Chevalier and Jean-Pierre Aumont were recruited to meet her at the airport. On her arrival, she carried a small, decorated cigar box which, as arranged, finally evoked a question about its contents when she stepped before the waiting microphones. It was, she said with a wink, the gown for her show. The following day (November 19) every Paris newspaper announced the imminent display of the scantiest costume outside the Folies-Bergère.

To old friends like Coward, such tactics made her “boring and over-egocentric, poor darling”; new acquaintances, like Paris correspondent Art Buchwald, found her curiously fascinating when she read him her best reviews and explained the two portions of her act—revealing gown for the first, white tuxedo and top hat for the second (bringing to life her final costume from Blonde Venus):

You could say that my act is divided between the woman’s part and the man’s part. The woman’s part is for men and the man’s part is for women. It gives tremendous variety to the act and changes the tempo. I have to give them the Marlene they expect in the first part, but I prefer the white tie and tails myself . . . There are just certain songs that a woman can’t sing as a woman, so by dressing in tails I can sing songs written for men.

Although there was, in 1959, a brief liaison with the athletically handsome forty-two-year-old Italian actor Raf Vallone, Marlene Dietrich by the end of the year had restricted her romantic life to her musical arranger and conductor Burt Bacharach, then thirty—“a man who took me to seventh heaven,” as she wrote later, often reverting to language hitherto reserved for her affair with Gabin.

He was the most important man in my life after I decided to dedicate myself completely to the stage [and] my highest goal until the day he left was to please him . . . I lived only for the performances and for him . . . With the force of a volcano erupting, Bacharach had reshaped my songs and changed my act into a real show. On tour, I washed his shirts and socks. In short, I took care of him as though he were my savior. And as a man, he embodied everything a woman could wish for. He was considerate and tender, gallant and courageous, strong and sincere; but above all, he was admirable, enormously delicate and loving. And he was reliable. His loyalty knew no bounds. How many such men are there? For me he was the only one . . . He was my lord and master.

And so Bacharach remained for several years of international travel with her and her show. His youth, charm and talent made him enormously attractive to Dietrich, who desperately required proof that she could still compete with younger women, and who knew few ways other than sex to fascinate a man she needed and to sustain his attention. For Bacharach’s part, the life of a bachelor/traveling musician could otherwise have been dismally lonely, and his simultaneously personal and professional intimacy with Dietrich quickly proved to be enormously valuable. Additionally, he indeed cared for her patiently, coping with her ego and her moodiness, her self-absorption, her constant need to be confirmed as an artist and as a woman. Twenty-eight years her junior, Bacharach was certainly among the most estimable to her. He was also, it seems, her last male lover.

To Burt Bacharach belongs at least part of the credit for perhaps the single most dramatic period of Dietrich’s seniority, for had he not encouraged and attended her she might not have returned to Germany in 1960—an event of which the success (not to say her safety) could not be guaranteed.

On Thursday, April 14 (following a three-week engagement in Lake Tahoe, Nevada), Dietrich and Bacharach arrived in London en route to Paris, where she had scheduled wardrobe fittings at Dior and Balenciaga. The German tour had just been announced, to include concerts in Berlin, Hamburg, Oldenburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, Cologne, Hanover, Wiesbaden, Munich, Stuttgart and Frankfurt (for which she would receive almost  4,000 for each performance). But when Noël Coward took her to dinner, she admitted that she had some hesitations about the journey. “She was in a dim mood,” he noted in his diary, “because all is in a state of chaos [and] the German press has come out against her.”

4,000 for each performance). But when Noël Coward took her to dinner, she admitted that she had some hesitations about the journey. “She was in a dim mood,” he noted in his diary, “because all is in a state of chaos [and] the German press has come out against her.”

In fact the pretour publicity then being generated was a horror, and it was much to Dietrich’s credit that she ignored the threats of danger and pressed on; she could, after all, have easily substituted engagements elsewhere. “If they had any character,” she had said in 1952, “the German people would hate me [for my entertainment of Allied troops].” Eight years later, that torn and divided land had “character” aplenty, but much of it was harnessed against Dietrich from March to the end of April, as warnings and vilifications filled the German press:

—“The USA and Germany are long since friends, but Dietrich is still leading a private war against the fatherland she unnecessarily gave up. Obviously she does not despise the Deutsch Mark as much as her homeland.” —Kölnische Rundschau (Cologne), March 3.

—“Who has invited this person who worked against us during the war to perform as a visiting actress? Marlene, go home!” —Bild-Zeitung (Berlin), March 3.

—“Marlene marched on the side of the Resistance fighters and the enemies of everything that was Germany. She did not keep still when Germans tried to dig themselves out of the ruins and misery and regain respect in the world. It would be better for us if she were to remain where she is.” —Badische Tagblatt (Baden-Baden), March 24.

—“She donned an Allied uniform and entertained their troops! While her actions can be understood during the Hitler regime, it is incomprehensible why she refused to change her mind after the war.” —Bild am Sonntag (Hamburg), April 3.

There was some (but not much) dissent: “If she is received with tomatoes and rotten eggs,” warned Hamburg’s Die Welt, “then our reputation in America will decline further, and it will prove anew that we have learned nothing from our mistakes.” And newspapers did receive a few letters like that from a woman in Düsseldorf: “Who showed more character—Marlene, who resisted all enticements to turn to Hitler and who fought uncompromisingly against criminal Nazi Germany, or we who went down on our knees before those wretched leaders? It’s not a very far journey from ‘Jews, get out!’ to ‘Out with Marlene!’ ”

But support for the returning Dietrich was essentially as flimsy as the chiffon of her gowns. As the date of her arrival drew near, letters to editors proliferated and privately circulated handbills opposing her littered every major German city:

—“An impudent wench fights for her honor by daring to come home. Dietrich has thousands of German soldiers’ graves on her conscience. She not only fought the Nazis but the German people as well! Now she is even enlisting help from Willy Brandt [mayor of West Berlin], the former resistance fighter. She is an antisocial parasite and should receive deserved punishment from us.”

—“Aren’t you, a base and dirty traitor, ashamed to set foot on German soil? You should be lynched, since you are the most wretched war criminal.” —Open letter from Mayen.

“The major error of this tour,” said the respected Belgian critic Jean Améry years later,

is that she thought she was returning home triumphantly. What she did not take into account was the unexpected self-assurance of the German citizenry and especially of West Berliners. With the economic recovery of Germany, people had regained their good conscience. And a new generation had grown up, too, for whom Dietrich meant very little—as the ghosts of Nazism meant very little to them.

The outcry against her return increased when Dietrich’s earlier unambiguous comments on Germany were loudly broadcast: “I was German but I refused to declare myself a supporter of a country in which such atrocities were taking place.” And when asked that spring whether she felt any sentiment about returning to her former home she replied coldly, “Not one bit. I gave up my fatherland because I was ashamed of it. Home is where my family is, and my family is in America.” Far from attempting to reconcile herself with her country, her return seemed more an act of defiance.

But Dietrich was not, nor had she ever been, ranked as a political person exploited as a German national or, later, as a naturalized German-American. At stake in 1960 was her adherence to a moral position from which she had never wavered a quarter-century earlier, when many of her compatriots were not at all convinced that Hitler was so bad after all. (“If I were a German,” added Améry, “I would be proud of her—and of her pride.”)

ON APRIL 30, 1960—FIFTEEN YEARS AFTER HER last visit—Marlene Dietrich arrived in Berlin, and on May 2 she strode into a hotel dining room and answered journalists’ questions in flawless, elegant German. Wearing the red ribbon of the French Legion of Honor and carrying a bouquet of lilies of the valley, she stared around, then sat down and spoke with remarkably cool assurance: “I am singing here because singing is my business, and I have been asked by my German agents to come. Why should I say no? . . . Am I afraid of rotten tomatoes? No, rotten eggs would be worse, because they could not be cleaned from my swansdown coat . . . Perhaps I will do some good, you say? I don’t want to do any good.” She felt, she told a friend that evening at the Berlin Hilton, “as though I’m going to my Nuremberg trial when I step out on that stage tomorrow night.”

With Danny Thomas, about 1949.

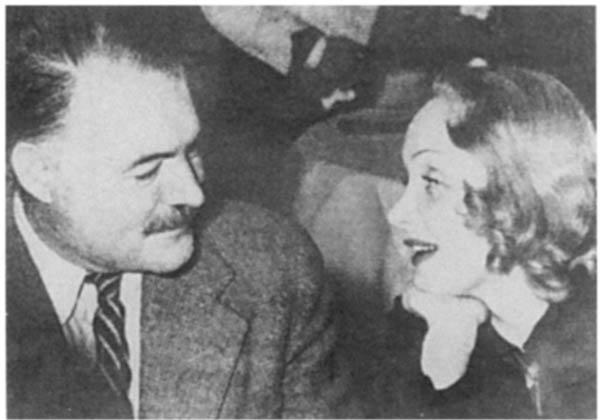

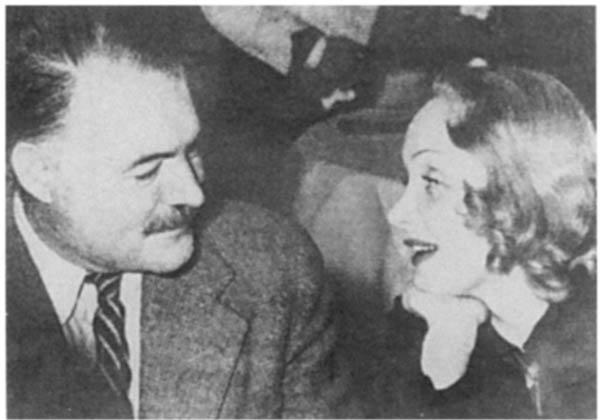

With Ernest Hemingway in New York, 1947.

With Maria in New York, 1950.

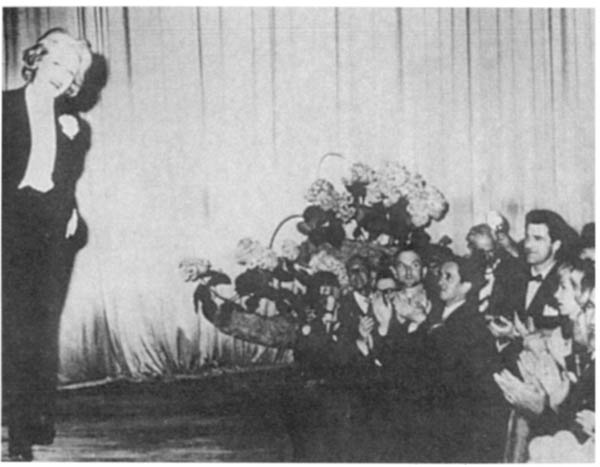

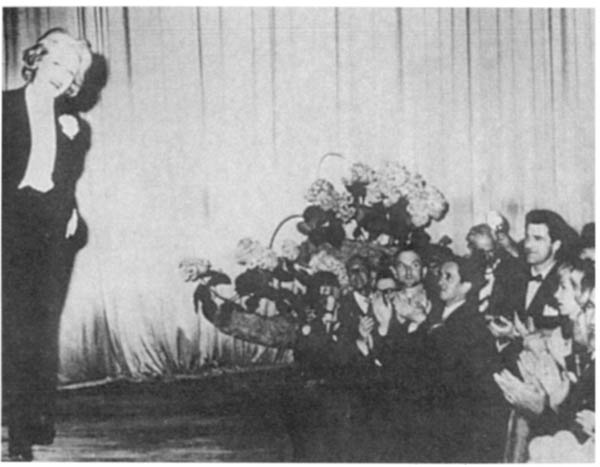

Opening night in Las Vegas, 1953.

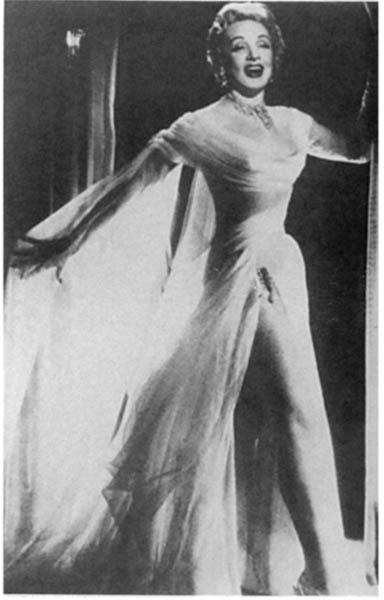

London, 1954.

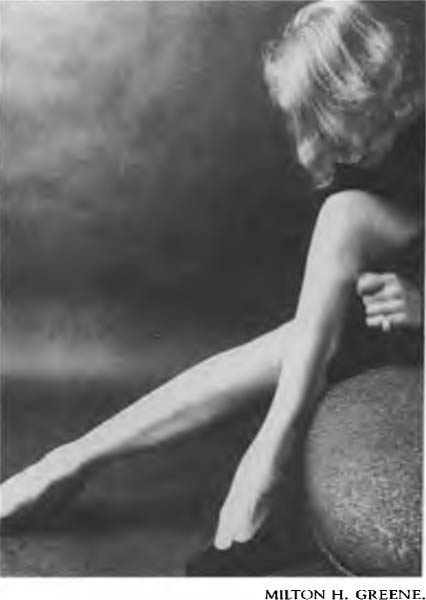

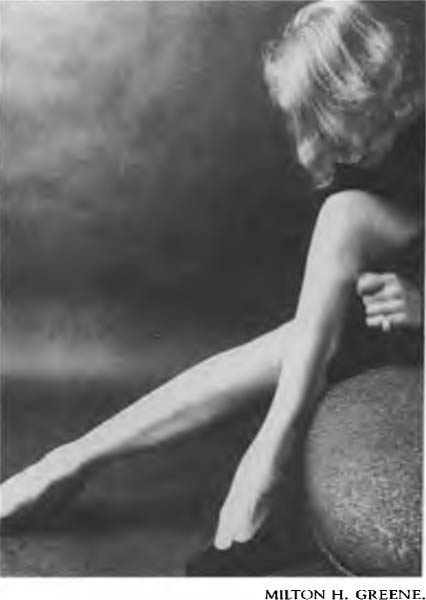

The famous legs, celebrated by photographer Milton Greene in 1955.

During filming of Witness for the Prosecution, with Charles Laughton, Tyrone Power and director Billy Wilder: Hollywood, 1957.

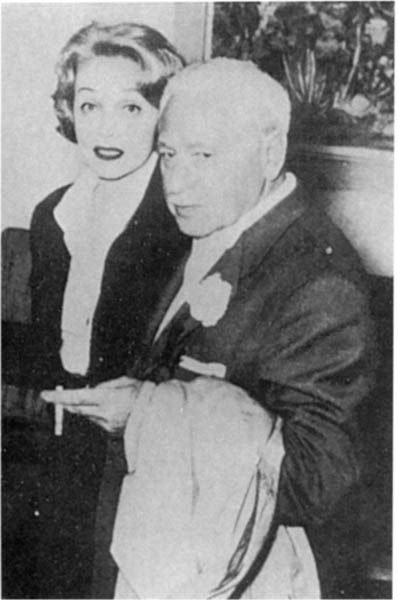

With Noël Coward, 1958.

At the Titania Palast: Berlin, May 1960.

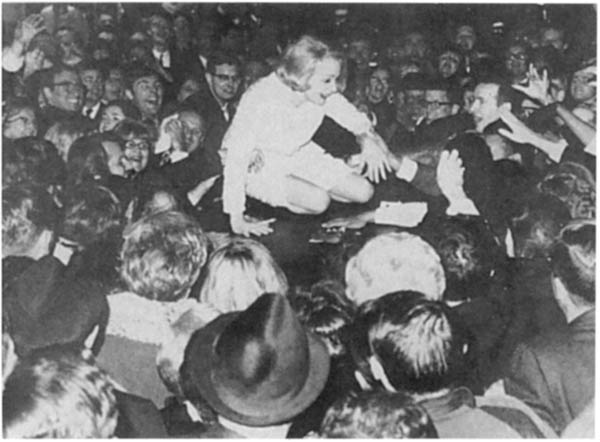

Crowds with placards urging “Marlene, go home!” outside the Titania.

At the Locarno Film Festival with von Sternberg, July 1960.

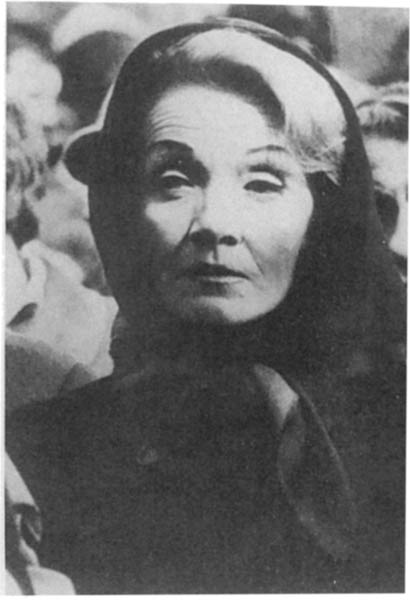

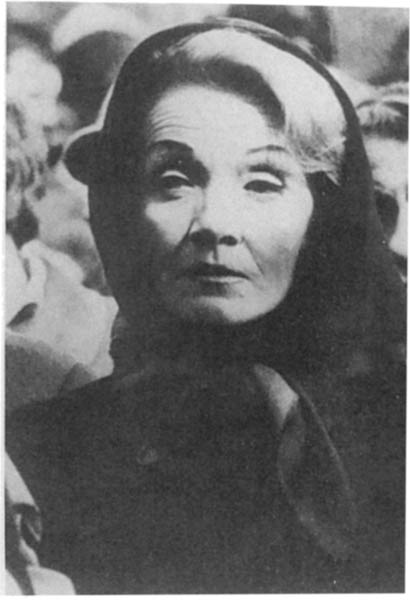

At the funeral of Edith Piaf: Paris, 1963.

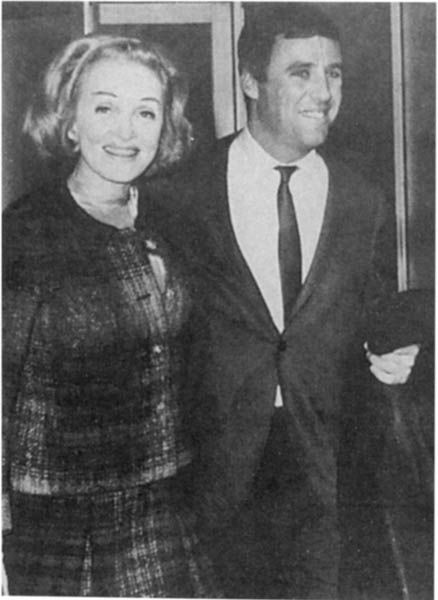

With her musical director Burt Bacharach: London, 1964.

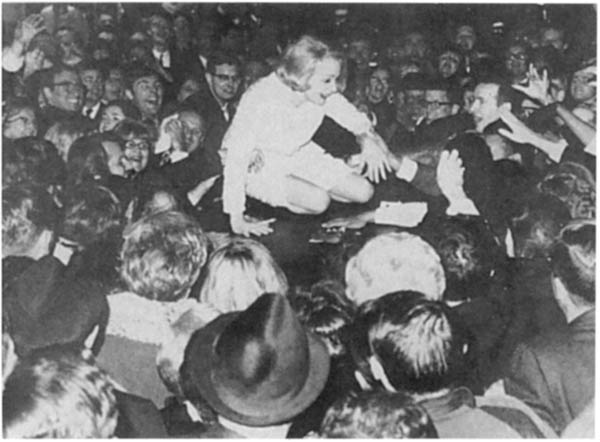

Outside the theater after the New York premiere of her one-woman show, October 1967.

On tour.

Dietrich’s last screen appearance, as the Baroness von Semering in Just a Gigolo, 1978.

On Sunday, May 1, a Berlin newspaper—in a triumph of Teutonic efficiency—announced the recovery of the certified birth certificate of Marlene Dietrich, who was about to step onto a German stage for the first time since 1929; she was born, the article proclaimed gleefully, on December 27, 1901.

On Tuesday, May 3, there were police precautions encircling the Titania Palast, after threats of riots, egg-pelting and a broadcast warning of the release of five hundred white mice in the theater aisles. Of two thousand seats, five hundred were empty for her premiere, but at prices ranging from two to twenty-four dollars the tickets were beyond the range of all but the most independently affluent Berliners. In her hotel room, Dietrich was moody and tense, impervious even to Bacharach’s reassurance. “I am not particularly glad to be here or there or anywhere,” she told an inquiring reporter. “All my former friends here either left Germany or died in concentration camps, and so there are none left for me to see.” She did not, she added with astonishing frankness, have any happy memories of Berlin at all.

Her attitude was, in fact, very like her act, in which Marlene Dietrich affected a stance bordering on cold contempt. Asking for nothing but attention, she offered a bluntness rarely heard from visiting performers, who ordinarily (then as later) insisted how much they loved the place they were performing in, what devoted friends and precious memories were evoked, how ineffably divine the experience was, what sheer love they felt. From Dietrich there was none of this bogus sentiment, no idle palaver. She was in a sense not ending the war once and for all, she was declaring the impossibility of a truce.

That evening, affecting a bravado she almost certainly could not have felt, Dietrich asked her driver to stop several blocks from the Titania and she walked the remaining distance. Outside the theater, a small crowd had gathered—mostly people her own age who had seen her more than thirty years before. One woman who depended on a cane and had no ticket simply wanted a glimpse, and she quickened her step to greet Dietrich at the stage door. Her name was Mrs. Erich Ernst, and although the two women had never met, bystanders might have thought they were old friends. “Dear Marlene,” said Mrs. Ernst, “please shake my hand.” And for just the flicker of a moment, as the two women joined hands and lightly caressed one another’s cheeks, a photographer captured the image—one of them smartly dressed in a tweed coat and fashionable hat, the other wearing a faded kerchief and shawl, but both of them with tears glistening.

An hour later, the houselights inside dimmed, the orchestra struck a drumroll, and the filmmaker Helmut Kräutner introduced Marlene Dietrich as “a woman who has been true to herself.” And then a hush descended on the audience as she entered, wearing a form-fitting dress that gave not quite the provocative illusions customary in Las Vegas. There were no catcalls, no rotten fruit, no mice, no ungracious or rude reactions. The applause began politely and then, with Mayor Willy Brandt leading the ovation, there was a more enthusiastic welcome. Except for a few rowdies outside on the street, denouncing her as a traitor and holding signs demanding her immediate removal from the country (“Marlene, hau ab!—Take off, but quick”), there was nothing to suggest hostility.

With a nod of her head, Dietrich simultaneously acknowledged the welcome and cued Bacharach. And then she began to sing—first “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuss auf Liebe eingestellt” from The Blue Angel—crooning for the thousandth time that she was primed for love from head to foot. For an hour, she offered her standard numbers—“Johnny,” “The Laziest Gal in Town,” “The Boys in the Back Room,” “One for My Baby,” some in English, others in German or French—but she never told the audience that she was singing just for them; she neither flattered nor appeased them, never asked or bestowed signs of false affection. Yet with each round of applause, the audience seemed more hers—even when she reminded them that she had not forgotten the past and would not repent a single moment of her decisions, a sign she gave by singing two songs by German Jews who had fled Hitler. These she specifically dedicated to the two composers—Richard Tauber (“a wonderful human being,” she said) and Friedrich Holländer, who had written the majority of her movie songs. There was only silence in the Titania when she announced these songs, but no mention of this at all in the overwhelmingly favorable reviews next day.

The theater was only three-quarters full (and half of those had been admitted on free passes), but the fifteen hundred spectators sounded like thousands. After her final number—a wistful rendition of a sentimental ballad called “I Still Have a Valise Left in Berlin” she delivered in her white tuxedo—Mayor Brandt rose to his feet, leading a thunderous eleven curtain calls.

“She won her battle from the first moment,” proclaimed Der Abend next day. “She stood there like a queen—proud and sovereign. According to the Bild-Zeitung, “Marlene came, saw and conquered,” to which the Berliner Zeitung added heroically, “She is not only a great artist, she is a lovable woman—she is one of us. Marlene Dietrich has really come home!”

Less grandly, an elderly lady leaving the theater had said to her companion, “That’s the old Marlene.”

Of course it had not been the old Marlene at all—neither the saucy chorine, the plump, bored repertory player, nor even the innocent destroyer of The Blue Angel. But there was something of the past for those who ransacked memories or longed for reconciliation. Dietrich’s now deep and reedy voice, to those who wanted to hear it so, was lined and sealed with recollections of a distant time, before an ocean of rancor and resentment separated her from Berlin. No matter how much had changed there, she had indeed come home. Without any counterfeit sweetness or phony tenderness, and after a mere one hour of song, she had rediscovered her lost role as a proud Prussian commanding both the stage and her hearers—courageous, insistently autonomous and, as her introducer had said, true to herself. To postwar Berlin, ringed with a wall, with fear, suspicion and remorse, she could have offered no greater benediction.

40,000 a week for four weeks), and few in her audiences seemed to care that there was less voice than ever. Everything about her appearances, in fact, seemed more and more frozen, stylized. Her shows were expanded in those years to include concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Sâo Paolo, Buenos Aires and Paris, where she added to her repertory American ballads (“My Blue Heaven,” for example), recent show tunes (“I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” from My Fair Lady), and German, French and Brazilian standards.

40,000 a week for four weeks), and few in her audiences seemed to care that there was less voice than ever. Everything about her appearances, in fact, seemed more and more frozen, stylized. Her shows were expanded in those years to include concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Sâo Paolo, Buenos Aires and Paris, where she added to her repertory American ballads (“My Blue Heaven,” for example), recent show tunes (“I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” from My Fair Lady), and German, French and Brazilian standards.