Nalanda Buddhist Society Malaysia

TEACHING THE DHAMMA, MALAYSIA

DEPENDENT ARISING is one of the most important teachings of the Buddha. Its essential principle is stated thus (MN 79:8):

When this exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises. When this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases.

The Buddha employs this principle of conditionality in a variety of circumstances, especially when explaining the twelve links of dependent arising, the causal process for taking saṃsāric rebirth and attaining liberation from it. Dependent arising is also used to prove selflessness.

As sentient beings, we exist in dependence on a body and mind, which themselves are dependent. Buddhaghosa explains (Vism 18:36):

[The body and mind] cannot come to be by their own strength,

nor can they maintain themselves by their own strength;

relying for support on other states…

they come to be with others as condition.

They are produced by…something other than themselves.

The twelve links describe how our bodies and minds come into being by depending on their causal factors and how they give rise to further unsatisfactory results. Our lives arise due to causes we ourselves create. A supernatural power or external agent does not cause our experiences. Nor is there a substantially existent person who creates kamma and experiences their results. Rather one link arises from another in a natural process of conditionality.

In the suttas, Buddha presents the twelve links in a variety of ways, starting at different points in the chain to give a variety of perspectives on causation. Here we will follow the sequence (SN 12:2, MN 9) that begins with our present experience—aging and approaching death—and works backward in the sequence. This explains how we arrived at this point in our lives. It is also the sequence found in the Buddha’s account of his own awakening, when he understood causation in its totality.

To fully understand each link, we need to understand its relation to its preceding and subsequent links, which are respectively its main cause and main effect. Contemplating these interlinking factors, we come to see our lives as a complex web of dependent causality. The following explanation from the Pāli tradition generally accords with that in the Sanskrit tradition.

Following the description of each link the question arises, “What is its origin, its cessation, and the path to its cessation?” The answer is that the previous link—the one that will be described next in this reverse ordering of the links—is the cause of this link. The cessation of the previous link brings the cessation of that link. The noble eightfold path is the path to its cessation. As you read below, you may want to pause after the description of each link to remember this.

12. Aging is the decline of life that begins immediately after birth; death is the dissolution of the body and mind of this life. Aging and death occur due to birth. Without being born, we would not age and die. To stop aging and death completely so that they are not experienced again, birth in saṃsāra must be stopped.

11. Birth, for human beings, is the time of conception, when the sperm, egg, and consciousness come together. This consciousness is the continuation of the mindstream of a being who left his former body and life. With it come all underlying tendencies of afflictions and kamma present in the previous life. These will condition many of the experiences of the new being. Birth is the “manifestation of the aggregates” of the new life. The five cognitive faculties of eye, ear, nose, tongue, and tactile are subtle material found deep inside each physical organ. They gradually develop so that contact with sense objects begins to occur.

In society, birth is seen as auspicious. This is because we do not see its inevitable result, death. When we train our minds to see the complete picture of life in saṃsāra, we will aspire for liberation.

There is discussion whether a period of time exists between death and the following rebirth. While no clear statement is found in the suttas, some passages suggest there may be a period of time between two lives. The Sanskrit tradition speaks of an intermediate state (antarābhava, or bardo in Tibetan) between one life and the next.

10. Renewed existence (or becoming) as a cause of birth refers to the kammic force that leads to rebirth in that particular state. The Visuddhimagga (17:250) distinguishes two aspects of renewed existence: (1) Active kamma of renewed existence is kamma that leads to a new rebirth: intentions and the mental factors of attachment and so forth conjoined with those intentions. It is the kammic cause propelling a rebirth. (2) Resultant rebirth existence is the resultant rebirth—the four or five aggregates propelled by kamma that experience the diverse results of our previous actions. Birth is the beginning of the resultant rebirth existence, aging is its continuation, and death is the end of that particular resultant rebirth existence. The Sanskrit tradition specifies renewed existence as the karma that is just about to ripen into the new rebirth.

During the time of this new life propelled by ignorance and kamma, many new kammas that will lead to future rebirths are created through our choices. Our choices are conditioned and limited by our previous actions and our current mental state, but they are not completely determined by them. We have the freedom to make responsible choices and nourish or counteract tendencies toward certain intentions.

9. Clinging makes us engage in activities that produce our next existence. It is of four types, clinging to (1) sensual pleasures, (2) wrong views other than the following two views, (3) a view of rules and practices—e.g., thinking self-mortification or killing nonbelievers is the path to good fortune—and (4) a view of self: an eternalist doctrine that holds there is a soul or self.

Clinging leads to renewed existence, birth, aging and death, and more dukkha. Therefore it is imperative to know the origin, cessation, and path to the cessation of clinging. It arises due to craving and ceases when craving ceases. The noble eightfold path is the way to cease clinging.

8. Craving is of three types: sensual craving, craving for renewed existence, and craving for nonexistence. These were explained in chapter 3.

Craving and clinging are closely related. An increase in craving stimulates clinging. The two bring dissatisfaction during our lives and great fear at the time of death, when we do not wish to separate from this life and cling to having another one.

7. Feeling is the nature of experience and has three types (pleasure, pain, and neutral), five types (physical pleasure, mental happiness, physical pain, mental pain, and neutral), or six types (feelings arising from contact through the six sources). So much of our lives is governed by our reactions to various feelings; we crave for pleasant feelings, crave to be separated from unpleasant ones, and crave for neutral feelings not to diminish. The latter applies especially to beings in the fourth jhāna and above, who have only neutral feelings and do not wish the peace of their state to cease.

One place where the forward motion of dependent arising can be broken is between feelings and craving. Feelings naturally arise as a result of previous kamma. By applying mindfulness and introspective awareness to our feelings, observing them as they are—impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless—we won’t react to them with any of the three types of craving. Then feelings will arise and pass away without the arising of craving, clinging, and the remaining links. In this way ariyas and arahants experience feelings without craving.

6. Contact is the mental factor of contact arising with the meeting of the object with consciousness by means of the corresponding base. It occurs when, for example, a visible object such as color, the eye cognitive faculty, and the visual consciousness come together to create perception of that color. Contact is of six types corresponding to the six objects and six sources that produce it and the six types of feeling that it stimulates.

5. Six sources refers to the six internal bases—eye, ear, nose, tongue, tactile, and mental—that generate consciousness. They are called “sources” because they are the sources for the arising of the six consciousnesses. They are internal because they are part of the psychophysical organism. Of these, the first five are sense sources and the sixth is a mental source. The bhavaṅga is included in the latter. Each internal source is particular to its own object and consciousness. If it is injured or unable to function, the corresponding sensory function is also impaired. The six external sources—form up to mental objects—are the objects of consciousness. Together, these twelve include all conditioned phenomena.

4. Name and form is mentality and materiality. In the Pāli tradition, name (nāma) refers to five mental factors that are indispensable for making sense of and naming things in the world around us—feeling, discrimination, intention, contact, and attention. These help us to organize the data that flow in through our six sources and render them intelligible. The Sanskrit tradition says name consists of the non-form aggregates. Form (rūpa) is the form aggregate—our body constituted of the four elements and forms derived from them.

The way the six sources arise from name and form can be understood in two ways. (1) As the psychophysical organism conceived in the mother’s womb develops, the six sources arise, and (2) the conditioning occurring in any cognition produces the six sources. For example, the eye source depends on the support of the body (material), which is alive due to the presence of consciousness and its accompanying mental factors (mentality).

3. Consciousness here refers to the mental consciousness that initiates the new life, connecting the mindstream from the previous life with the new life. It simultaneously gives rise to the five mental factors that are called “name”—a shorthand term for the mental side of existence—and animates the new physical body, or “form.” Without consciousness, the five mental factors of name cannot occur, and the body cannot function as a living being.

The six primary consciousnesses also condition name and form whenever we cognize an object. When consciousness is not present, the body dies and the six cognitive faculties cannot connect their corresponding objects and consciousnesses to produce cognition and contact.

Consciousness maintains the continuity of an individual’s existence within any given life from birth until death and then beyond. It carries with it memories, kammic latencies, and habits, connecting different lives and making them into a series allowing later moments of consciousness to arise from former moments of consciousness and enabling future lives to relate to previous ones.

2. Formative actions are all the nonvirtuous and mundane virtuous intentions or kamma that bring rebirth in saṃsāra. While sense consciousnesses themselves do not create kamma, due to their contact with objects, virtuous and nonvirtuous mental factors arise in our mental consciousness and create kamma.

Not all kammas lead to rebirth. Weak intentions, neutral intentions, and physical and verbal actions that are incomplete lack the strength to produce saṃsāric rebirth. Supramundane virtuous intentions—those performed by ariyas—are not formative actions in relation to the twelve links because they do not perpetuate saṃsāra.

Formative actions may be meritorious, demeritorious, or unwavering, leading, respectively, to fortunate rebirths in the desire realm, unfortunate rebirths, and rebirth in the material or immaterial realms. (According to the Pāli tradition, rebirth in the material realm is the result of meritorious kamma.)

Formative actions generate rebirth into a new existence by serving as the condition for the consciousness that takes birth. This occurs in two ways. First, during our lives, we create kamma when we think, speak, and act. These intentions occur along with consciousness and also affect consciousness. Second, at the time of death, previous kamma is activated and propels the consciousness through the death process into a new existence. Formative actions determine whether this new consciousness is one of a human, animal, and so forth, corresponding with the body it has entered. Kamma accumulated in previous lives also determines which environment we are born into, the situations we experience, our habitual tendencies, and the feelings we experience.

While previous kamma influences consciousness, in general it is not an unalterable determining force. At any moment in our waking lives, we have the potential to change the course of our lives by changing our intentions.

1. Ignorance is the lack of understanding of the four truths. Oblivious to the three characteristics of conditioned phenomena, ignorance does not understand dependent arising and thus keeps us bound in saṃsāra. Mādhyamikas say ignorance apprehends the opposite of reality, grasping persons and phenomena as inherently existent when they are not.

As the first link, ignorance is the condition for the arising of both virtuous and nonvirtuous formative actions. Rooted in the underlying tendency (anusaya, anuśaya) of ignorance, attachment, anger, and other polluted mental factors motivate nonvirtuous actions. Ignorance also conditions virtuous mental states such as love and compassion in ordinary sentient beings. Only when ignorance is eradicated do all formative actions and saṃsāric rebirths cease.

Ignorance in one life is conditioned by ignorance in the previous life. There is no first moment of ignorance; thus saṃsāra is beginningless. However, ignorance can cease, and the path to that cessation is the noble eightfold path. When an ariya understands the pollutants, their origin, cessation, and the way to that cessation, she eradicates all underlying tendencies leading to saṃsāric rebirth and attains liberation.

Dependent arising applies not only to saṃsāra and what keeps it going (the first two truths of the ariyas) but also to liberation and the path that brings it about (the last two truths). Liberation has its nutriment—the seven awakening factors—and the links of conditioning factors leading to these are the four establishments of mindfulness, the three ways of good conduct, restraint of the senses, mindfulness and introspective awareness, appropriate attention, faith, listening to the true Dharma, and association with superior people (AN 10:61–62).

In explaining these forward and reverse series of causation for both saṃsāric existence and liberation, the Buddha does not imply that any one factor arises due to only the preceding factor. Rather he emphasizes that a momentum builds up as the various factors augment each other. In short, everything has multiple conditions, some more evident, others deeper. These conditions form a web of interrelated factors. It is like looking up a topic on the Internet. One page leads to five others, each of which takes us in a different but related direction.

Pāli commentaries explain the twelve links in terms of four groups, each with five links. This clarifies the relationships of the twelve links and the different lifetimes in which they occur. In the following table, lives A, B, and C occur in sequence, with life B being the present life.

Life |

Links |

Twenty Modes (four groups of five) |

A |

Ignorance (1) Formative actions (2) |

Five past causes 1, 2, 8, 9, 10 |

B |

Consciousness (3) Name and form (4) Six sources (5) Contact (6) Feeling (7) |

Five present results 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

B |

Craving (8) Clinging (9) Renewed existence (10) |

Five present causes 8, 9, 10, 1, 2 |

C |

Birth (11) Aging and death (12) |

Five future results 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

The “links” column shows that our present life, B, is rooted in the ignorance and formative actions of a preceding life (A). Through the maturation of kamma (formative actions) conditioned by ignorance come the five resultant factors in this life (B): consciousness, name and form, six sources, contact, and feeling.

In this life (B), when feeling occurs, craving arises. That leads to clinging, which generates the active kamma of a renewed existence. These three are the force generating another rebirth (C) during which birth and aging and death are experienced.

In any given life all these factors intermesh. To understand how the twelve factors function in this life, we look to the last column with its twenty modes that fall into four groups of five each.

1. Five past causes. In the previous life, ignorance and formative actions as well as craving, clinging, and the active kamma of renewed existence were causes for the present life.

2. Five present results. Those five causes brought about the five present results: factors 3–7, which are an expanded way of speaking of birth and aging and death.

3. Five present causes. Five causes existing in this life—craving, clinging, renewed existence, ignorance, and formative actions—bring about a future birth. While these are the same as the five past causes leading to the present life, now they arise in the present life and condition the future life.

4. Five future results. Links 3–7—which include birth and aging and death—arise in the future life due to the five present causes.

The above explanation corresponds with the explicit teaching in the Śālistamba Sūtra, a Sanskrit sūtra, in which the items in the second column are respectively called propelling causes, propelled results, actualizing causes, and actualized results. Here link 3, consciousness, consists of the causal consciousness upon which the karmic seeds were placed and the resultant consciousness at the time the karmic seeds ripen. The former is a propelling cause, and the latter is a propelled result.

The twelve links can also be classified into three groups: (1) Afflictions—ignorance, craving, and clinging—underlie the entire process of rebirth by acting as the conditioning force for kamma. (2) Kamma—formative actions and the active kamma of renewed existence—actually propel rebirth. (3) Results—consciousness, name and form, six sources, contact, feeling, resultant rebirth existence, birth, and aging and death—are resultant dukkha.

The Sanskrit tradition speaks of the twelve links in terms of the afflictive side—how cyclic existence continues, and the purified side—how cyclic existence ceases. Each side has a forward and reverse order. These four combinations correspond to the four truths of the āryas. Emphasizing true origins of duḥkha, the forward order of the afflicted side begins with ignorance and shows how it eventually leads to aging and death. The reverse order of the afflicted side emphasizes true duḥkha. It begins with aging and death and traces back through birth and so forth to ignorance.

The purified side is the process of attaining liberation. The forward order of the purified side speaks of true paths by emphasizing that by ending ignorance, all the other links will cease. The reverse order of the purified side speaks of true cessations and liberation by emphasizing that beginning with aging and death, each link ceases with the cessation of its preceding link.

Sāriputta makes one of the most famous statements in the Pāli suttas (MN 28:28):

Now this has been said by the Blessed One: “One who sees dependent arising sees the Dhamma; one who sees the Dhamma sees dependent arising.”

Here “Dhamma” refers to truth, reality. It also refers to the Buddha’s doctrine. Understanding dependent arising is the key to understanding both of these. It is also the key to countering saṃsāra. The Buddha says (DN 15:1):

This dependent arising, Ānanda, is deep and appears deep. Because of not understanding and penetrating this Dhamma, Ānanda, this generation has become like a tangled skein…and does not pass beyond saṃsāra with its planes of misery, unfortunate births, and lower realms.20

In addition to the twelve links, the dependent evolution of saṃsāra can be explained by dissecting an instance of cognition (MN 28). In dependence on an intact cognitive faculty, an impinging object (these two are included in the form aggregate), and attention to that object, the eye consciousness arises. Together with it are factors of all five aggregates: visual form, eye faculty, feeling, discrimination, mental factors from the volitional factors aggregate, and the primary eye consciousness are all present. This is another way in which the five aggregates come into being dependent on causes and conditions, not under their own power. When the conditions are not present, the aggregates do not arise, and dukkha is ceased.

The noble eightfold path that eradicates the origins of dukkha is also conditioned. Thus it can be practiced and cultivated. Developing the path will eradicate the origins of dukkha, leading us to the unconditioned, nibbāna, true peace.

In a Pāli sutta (SN 12:35) when a monk asks, “For whom is there this aging and death?” the Buddha responds that this is not a valid question because it presupposes a substantial self. If someone thinks the self and the body are the same and thus the self becomes totally nonexistent when the body dies, there would be no need to practice the path because saṃsāra would end naturally at the time of death. This is the extreme of annihilation.

If someone thinks the self is one thing and the body is another and that the self is released from the body at death and abides eternally, he falls to the extreme of eternalism. If the self were permanent and eternal, the path would be unable to put an end to saṃsāra because a permanent self could not change.

Not only did the Buddha refute a substantial self that is born, ages, and dies, he also denied that the body—and by extension the other aggregates—belong to such a person (SN 12:37). This body is not ours, because no independent person exists who possesses it. It does not belong to others, because there is no independent self of others.

Buddhaghosa answers the question, “Who experiences the result of kamma?” by quoting an ancient Pāli verse and then explaining it (Vism 17:171–72):

“Experiencer” is a convention

for mere arising of the fruit;

they say “it fruits” as a convention

when on a tree appears its fruit.

Just as it is simply owing to the arising of tree fruits, which are one part of the phenomenon called a tree, that it is said “the tree fruits” or “the tree has fruited,” so it is simply owing to the arising of the fruit consisting of the pleasure and pain called experience, which is one part of the aggregates called devas and human beings, that it is said, “A deva or a human being experiences or feels pleasure or pain.” There is therefore no need at all here for a superfluous experiencer.

The words “experiencer” and “agent” are mere conventional labels. There is no need to assert a findable experiencer of kamma or a findable creator of kamma. Such a self is superfluous because we say “A person experiences pleasure or pain” simply because that feeling has arisen in that person’s feeling aggregate. In speaking of the four truths, Buddhaghosa says (Vism 16:90):

…in the ultimate sense all the truths should be understood as void because of the absence of any experiencer, any doer, anyone who is extinguished, and any goer. Hence this is said:

For there is suffering but no one who suffers;

doing exists although there is no doer;

extinction is but no extinguished person;

and although there is a path, there is no goer.

Similarly, Mādhyamikas say that although we speak of a person who revolves in saṃsāra—one who creates karma and experiences its effects—this does not imply an inherently existent self. The resultant factors arise due to causal factors, which are themselves caused by other factors.

Similarly, there are no inherently existent āryas approaching nirvāṇa, and their going on the path—their activity of practicing—cannot bear analysis searching for their ultimate mode of existence. Still, āryas realize emptiness, purify their minds, attain awakening, and become qualified guides for others on the path. While all these agents and actions are not findable under ultimate analysis and have no inherent essence, they exist and function on the conventional level by being merely designated. Because they still mistakenly appear as inherently existent to āryas in post-meditation, they are said to be false, like dreams, illusions, mirages, and reflections.

We say “I studied hard as a child” from the perspective of our present I being a continuation of that child. The child self and the present self are different, yet because they exist as members of the same continuum, the adult experiences the result of the child’s actions. The process is similar from one life to the next: the self of one life isn’t the same as the self of the next, yet the latter experiences the results of the karma done by the former because they are members of the same continuum.

Mike Nowak

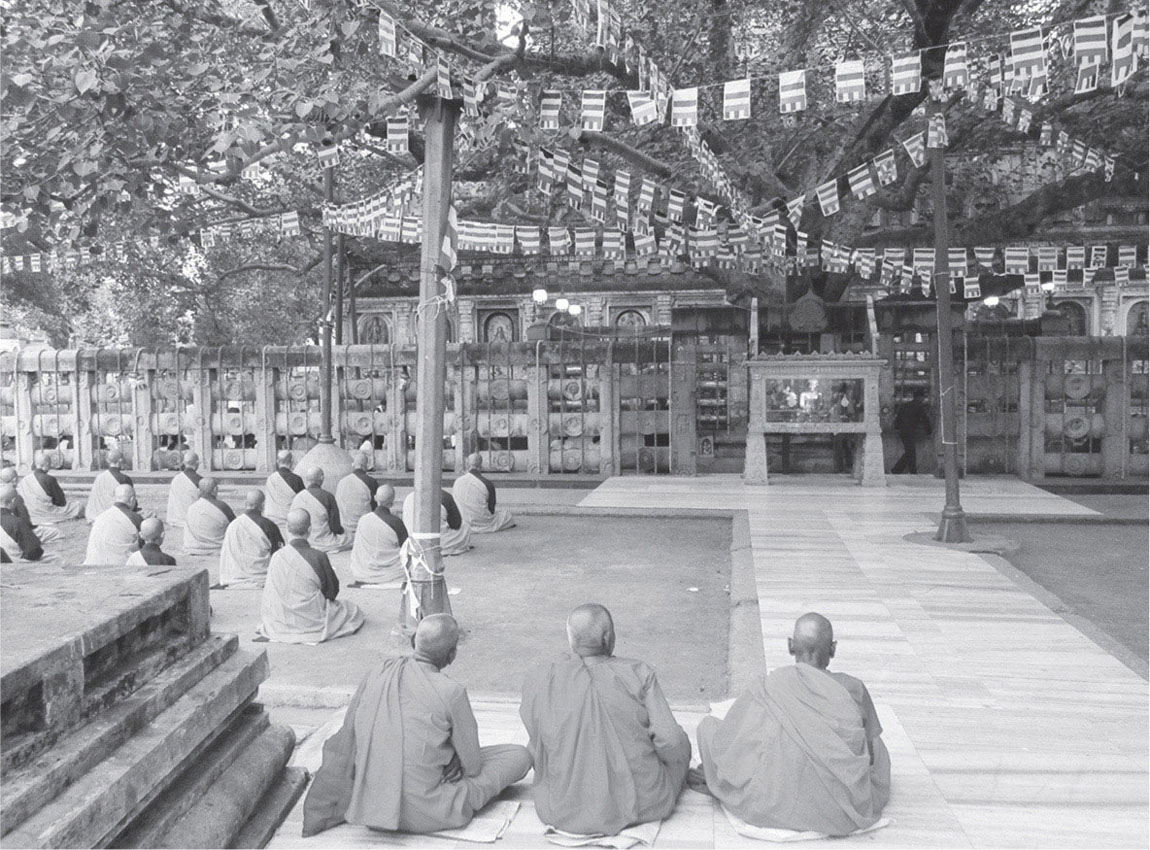

CHINESE AND SRI LANKAN MONASTICS UNDER THE BODHI TREE, BODHGAYA, INDIA

Of the different levels of dependent arising, the Sanskrit tradition explains this process of dependent arising as causal dependence. Each link arises dependent on the preceding one; understanding this counteracts the extreme of eternalism, thinking that the links exist inherently or thinking that an external creator causes duḥkha. When each link is complete, it gives rise to the subsequent links; understanding this eliminates the view of annihilation, thinking that things totally cease.

Understanding causal dependence leads to insight into selflessness. We see there is no substantial person underlying the process of dependent arising and there are no inherently existent persons or phenomena that are bound to saṃsāra or liberated from it.

Reflection on causal dependence clears away wrong views, such as believing our duḥkha arises without causes or is due to an external creator or a permanent cause. Identifying that ignorance and formative actions cause future lives eliminates the wrong view that everything ceases at death. We also realize our actions have an ethical dimension and influence our experiences. Seeing the variety of realms we may be born into ceases the misconception that no other life forms exist. Furthermore, we understand that all the causes of suffering exist within us. Therefore relief from suffering must also be accomplished within ourselves.

Contemplating each link individually accentuates its unsatisfactory nature. Seeing the beginningless, unsatisfactory nature of saṃsāra stimulates strong renunciation and energizes us to make effort to terminate it. We ask ourselves, “What sense does it make to crave worldly pleasures when attachment to them brings endless rebirth?” Bodhisattvas meditate on the twelve links with respect to themselves and other sentient beings. This arouses their compassion, which spurs bodhicitta. They want to attain full awakening to be fully competent to lead others on the path out of saṃsāra. Bodhisattvas’ compassion is so intense that if it were more beneficial for sentient beings for bodhisattvas to delay their own awakening, they would joyfully do this. However, seeing that they can be of greater benefit to others after they become buddhas, they exert effort to attain buddhahood as quickly as possible.

The following sections discuss the unique Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka approach to dependent arising—because all phenomena are dependent, they are empty of inherent existence; because they arise dependent on other factors, they exist conventionally. Understanding this compatibility of dependent arising and emptiness—especially that karma and its results function although they lack inherent existence—enables us to practice the path to liberation and full awakening.

There are different ways of explaining and understanding dependent arising. According to one presentation, (1) arising through meeting refers to effects arising from causes. This is causal dependence and pertains only to impermanent things and is common to all Buddhist traditions. (2) Existing in reliance indicates that all phenomena depend on their parts. This applies to both permanent and impermanent phenomena. (3) Dependent existence refers to all phenomena existing by being merely designated in dependence on their basis of designation and the mind that conceives and designates them.

In another presentation of dependent arising, there are two levels: (1) causal dependence indicates that effects arise due to their own causes, and (2) dependent designation has two implications: (a) mutual dependence is phenomena’s being posited in relation to each other, and (b) mere dependent designation refers to phenomena existing as mere name or mere designation. “Mere name” does not mean things are just words or sounds—that clearly is not the case. It means they exist by being merely designated.

In both presentations, the “arising” in dependent arising is not limited to arising due to causes and conditions but extends to other factors contributing to phenomena’s existence. Also, in both presentations, the earlier levels of dependent arising are in general easier to understand than the latter and serve as a foundation to understand the latter ones. Focusing on the second presentation, let’s look at these levels of dependent arising in more depth.

Dependence on causes and conditions is the meaning of dependent arising presented in both the Pāli and Sanskrit canons and practiced in the Śrāvaka, Pratyekabuddha, and Bodhisattva vehicles. This is the meaning explored above in the twelve links of dependent arising.

Because causal dependence is a fact, holding things to exist with an inherent nature is untenable. If things existed inherently or independently, they could not arise due to causes and conditions. Contemplating causal dependence leads us to understand that all functioning things do not exist by their own power. That they arise dependent on causes and conditions indicates that they exist. Thus they are both empty and existent.

Based on causal dependence, mutual dependence and mere dependent designation are explained in the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras. Causal dependence is not too difficult to understand: we know that flowers grow from seeds, that knowledge comes from learning. Yet we don’t usually think that causes depend on their effects.

On the basis of observing causal dependence, deeper reflection leads us to recognize the mutuality of the relationship. Not only does the effect depend upon the cause, but also the cause depends upon the effect. Although a cause does not arise from its effect, the identity of something as a cause depends upon there being an effect. A seed becomes a cause because it has the potential to produce its effect, a sprout. Without the possibility of a sprout arising, the seed cannot be a cause. This is not mere semantics; the meaning is deeper.

Things have no inherent identity as either a cause or an effect. When the term cause is imputed to a seed, nothing in the seed objectively makes it a referent for the term cause. The same holds true for an effect.

There are many obvious examples of things existing in mutual dependence on one another. East and west, suffering and happiness, goer and going, designated object and basis of designation, spiritual practitioner and path, whole and parts, ordinary being and ārya—all these are posited in relationship to each other.

Some pairs that are mutually dependent are also causally dependent, such as yesterday’s mind and today’s mind. However, many are not. Someone becomes an employer because he or she has employees and vice versa. None of our social roles are self-existent; they exist mutually dependent on each other.

Actions are called “constructive” or “destructive” not because they are inherently so. Constructive and destructive actions or karma are posited not only in relation to each other but also in dependence upon their results. When sentient beings experience happiness, the actions causing that are called “constructive,” and when they experience suffering, those causative karmas are termed “destructive.”

Agent, action, and object of action—giver, giving, recipient, and gift—are likewise mutually dependent upon each other. A generous action exists dependent on these three.

Whole and parts also depend on each other. A car (a whole) is dependent on an engine, wheels, and so forth (its parts), and a wheel is a “car part” because cars exist. Both permanent and impermanent phenomena depend on their parts. The mind depends on a continuity of moments of consciousness. Atoms are composed of even smaller particles. No smallest particle or moment of consciousness can be found because everything consists of parts. Emptiness, too, depends on parts. The generality emptiness is designated in dependence on the emptiness of the table, the emptiness of the chair, and so on. Emptiness also depends on phenomena—persons, aggregates, and so forth—that are empty. Thus emptiness is not an independently existent absolute.

Delving deeper, we see that phenomena exist by being merely designated in dependence on their bases of designation. There is a designated object—a table—and its basis of designation—the collection of legs and top. The mind conceives the collection of these parts as a table and designates it “table.” If we try to find an essence—the true referent of the word “table”—we can’t find anything that is the table in the individual parts or in the collection of parts. Nothing in the parts can be objectifiably identified as the table. Dependence on other factors means that phenomena are empty of inherent existence.

When “snake” is imputed to a coiled, speckled rope in a dimly lit area, nothing on the side of the rope is a snake. Similarly, when we impute “snake” in dependence on a long coiled being, nothing on the side of that being—its body, mind, or the collection of the two—is a snake. We may think, “But there has to be something that is a snake from the side of the coiled being. Otherwise there is no reason for it, and not the coiled rope, to be a snake.” However, when we search for something that makes the coiled being a snake, we can’t pinpoint anything.

Similarly, when I is designated in dependence on the aggregates, there is nothing from the side of the aggregates that is I or me. The person is not one aggregate, the collection of aggregates, or the continuum of the aggregates.

What makes designating “snake” in dependence on a long, coiled being or designating “I” in dependence on the aggregates valid, while designating “snake” on a rope and “I” on the face in the mirror erroneous? The coiled being can perform the function of a snake, and the I can function as a person. The coiled rope and the reflection of a face cannot perform those functions.

The fact that things exist dependent on being merely designated does not mean that whatever our mind thinks up is real or that whenever we designate something with a term, it becomes that object. Thinking there are real people in the television doesn’t mean there are, and calling a telephone “grapefruit” doesn’t make it one.

Three criteria establish something as existent: (1) It is well known to a conventional consciousness—some people can identify the object. (2) It is not discredited by another conventional reliable cognizer—the perception of someone with unimpaired senses does not negate that. (3) It is not discredited by ultimate analysis—a mind realizing emptiness cannot refute its existence. In short, while all conventionally existent phenomena exist by being merely designated by mind, everything that is designated does not necessarily exist conventionally.

The levels of dependence are related to each other. We know through direct experience that things depend on causes and conditions: certain medicines cure particular diseases, and pollution adversely affects our health. By reflecting deeply on the observable fact of causal dependence, we will see that the ability for effects to arise from causes is due to their being interdependent by nature. Their possessing an interdependent nature enables causal influences to produce effects when suitable conditions come together.

But what makes phenomena have this dependent nature? Through examination, we see that only because everything lacks inherent existence and nothing is a self-enclosed, independent entity can things have a dependent nature that enables them to have conditioned interactions with other things. Thus, on the basis of the observed fact of causal dependence, we go through this chain of reasoning culminating in the realization of the emptiness of inherent existence, which, in turn, enables us to understand that all phenomena exist by mere designation, mere name.

Although phenomena are empty of inherent existence, they exist. We see that each thing has its own effects. How do they exist? There are only two possibilities: either inherently in their own right or by mere designation. Probing deeper, we see that inherent existence—phenomena existing from their own side, unrelated to anything else—is untenable. If they possessed such reality, the more we searched for their identity, the clearer it should become. In fact, when we subject phenomena to critical analysis, they are unfindable, indicating that they lack inherent, independent, or objective existence. When we understand that things exist but not inherently, the only conclusion we can reach is that they exist depending on mere designation by term and concept, i.e., by thought and language. Since they do exist, their existence can only be established on the level of dependent designation. In this way, understanding emptiness in terms of causal dependence eventually leads us to understand dependent arising in terms of emptiness.

Emptiness and dependent arising are seen as fully integrated and noncontradictory after arising from meditative equipoise on emptiness. The world does not cease to exist with the realization of emptiness; rather, our understanding of how it exists becomes more accurate. The I, aggregates, karma and its effects, and other phenomena are falsities in that they do not inherently exist although they appear to do so to our ordinary senses. Knowing they exist dependently, not inherently, enables us to relate to people and our environment in a more spacious way. Nāgārjuna says (MMK 24.18–19):

That which arises dependently

we explain as emptiness.

This [emptiness] is dependent designation.

Just this is the middle way.

Because there is no phenomenon

that is not dependently arisen,

there is no phenomenon

that is not empty.

Arising dependent on other factors—such as causes and conditions, parts, and term and concept—is the meaning of emptiness of inherent existence. Because actions depend on other factors, they produce results. This would be impossible if they existed inherently or independent of other factors. This understanding, which unites dependent arising and emptiness, negates both inherent existence and total nonexistence. Dependent arising and emptiness are inseparable qualities of all existents. It is the true middle way.

Although emptiness and dependent arising are compatible and come to the same point, they are not the same. If they were, then just by perceiving an instance of dependent arising, such as a book, or the principle of dependent arising, we would perceive emptiness. Empty and arising dependently are two ways of looking at phenomena. The fact that they are empty does not prevent conventional distinctions among objects. Pens and tables still have their own unique functions. Someone who realizes emptiness discerns these when she emerges from meditative equipoise on emptiness.

If dependent arising referred only to causal dependence, it would refute the inherent existence of only causally conditioned phenomena. Because here “dependent arising” means dependent designation, it establishes the emptiness of all phenomena. To understand this subtlest level of dependence, understanding mutual dependence is necessary, and to understand that, understanding causal dependence is vital. These three levels of dependence are progressively subtler although they are not mutually exclusive.

Dependent arising is called “the king of reasonings” because it not only negates independent existence but also establishes dependent existence. The term dependent arising itself shows the middle way view that phenomena are empty and yet exist. “Dependent” shows they are empty of independent existence, eliminating eternalism. “Arising” indicates they exist, eliminating annihilation. All phenomena that exist lack any inherent nature; nevertheless, they exist dependent on other factors and are established by reliable conventional consciousnesses.

The Buddha explains the danger of not correctly understanding terms and concepts (SN 1:20):

Those who go by names, who go by concepts,

making their abode in names and concepts,

failing to discern the naming process,

these are subject to the reign of death.21

The commentary says what “goes by names and concepts” is the aggregates. When ordinary people perceive the aggregates, their minds misconceive them to be permanent, pleasurable, and having or being a self. Due to distorted conceptions, people then “make their abode in names and concepts,” generating all sorts of afflictions in relation to the aggregates. People familiar with the Madhyamaka view may understand these same verses from that perspective.

The Itivuttaka commentary explains the same verse saying that beings “who make their abode in names and concepts” apprehend the aggregates as I or mine, or when the aggregates are not their own, they apprehend them as another person. Those who do this are subject to death and rebirth in cyclic existence. The sutta continues:

He who has discerned the naming process

does not suppose that one who names exists.

No such case exists for him in truth,

whereby one could say: “He is this or that.”

Someone who understands the naming process understands the aggregates and knows them as impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless and abandons craving for them by actualizing the supreme path. This arahant does not grasp what is labeled as I, mine, or “my self” in dependence on the aggregates to be a real person. After leaving behind the aggregates and attaining nibbāna without remainder, the arahant cannot be said to be “this or that.”

In several suttas, the Buddha explains that seeing not-self (selflessness) with wisdom does not destroy conventional discourse and the ability to communicate with others through the use of language. Conventional discourse, he says, does not necessitate grasping a self. Words, names, expressions, and concepts can be used by arahants who have eliminated all self-grasping.

The Buddha clarifies that an arahant uses words and concepts in accord with how things are done in the world, without grasping them as self. An arahant with his last saṃsāric body still uses conventional language that corresponds to how ordinary beings speak (SN 1:25). The commentary says “they do not violate conventional discourse by saying, ‘The aggregates eat… the aggregates robe.’” If they didn’t speak in a way that others could understand, how could they teach the Dhamma?

While arahants use words such as “I,” “mine,” and “my self,” this does not indicate they are subject to the conceit “I am.” They are beyond conceiving due to craving, views, and conceit.

The Buddha elucidates (DN 9:53), “There are merely names, expressions, turns of speech, designations in common use in the world, which the Tathāgata uses without grasping them.” Names and concepts can be used in two ways: someone who has ignorance and the view of a personal identity uses words and concepts believing there is a true object to which they refer, a self in these phenomena. Those free from ignorance and the view of a personal identity do not grasp at true referents of words and concepts. They use them merely as conventions to convey a meaning, without grasping at a self in the objects to which they refer.