Pureland Marketing

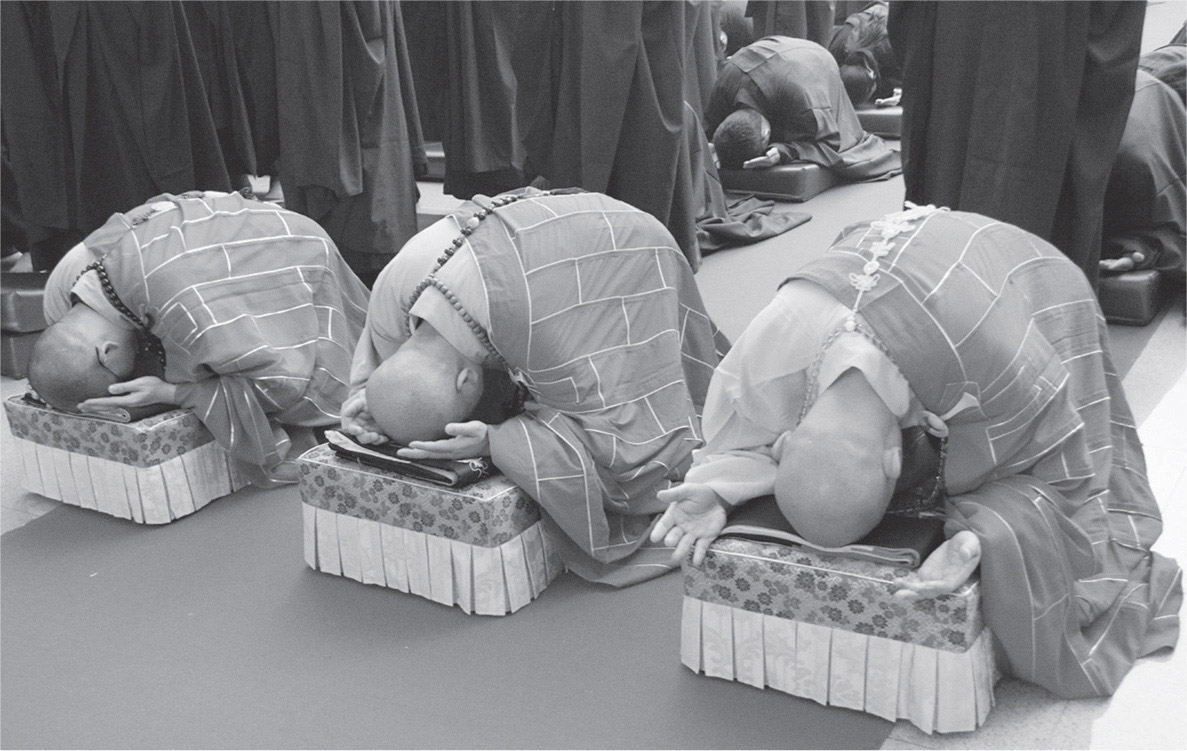

CHINESE MONASTICS BOWING

14 | The Possibility of Awakening and Buddha Nature

IF THE POSSIBILITY of ending duḥkha exists, then pursuing that aim is worthwhile. Two factors make liberation possible: the nature of the mind is clear light (pabhassara, prabhāsvara), and the defilements are adventitious.

According to the Sanskrit tradition, the clear-light nature of the mind refers to the basic, vivid nature of the mind—its clear and cognizant conventional nature that enables it to cognize objects. This capacity for the mind to be aware of or to know objects is already there; it does not have to be cultivated newly.

The mind’s inability to know certain objects must then be due to obstructing factors. A material object, such as a wall, obstructs us from seeing what is beyond it. An object being too far away or too small makes it unperceivable to normal senses. Damage of the cognitive faculty—for example, being blind—inhibits our knowing a visual object. The type of cognitive faculties and brain of the realm we are born into can obstruct knowing objects. Human ears cannot hear sounds that many animals can, and animal brains inhibit elaborate conceptual knowledge and the use of language.

A further difficulty is that some things—for example objects known by the six superknowledges—are so subtle, profound, or vast that the ordinary mind is unable to cognize them. To know these, deep meditative concentration, sometimes coupled with correct wisdom, is needed.

The subtle latencies of ignorance on the mind and the mistaken appearances and perceptions they generate prevent us from knowing all phenomena. When the wisdom realizing the subtle selflessness of all phenomena has completely removed every last mental obscuration, the mind will naturally perceive all objects because there will be nothing to prevent this. Thus a buddha’s mind is omniscient, capable of simultaneously realizing all phenomena, including their emptiness, in a single cognitive event.

The basic nature of the mind is clear like water. Any dirt in the water is not the nature of water and can be removed. No matter how murky the water is, its essential clarity is never lost. Similarly, afflictions are adventitious; they have not penetrated the basic nature of the mind. Not every instance of the mind’s clarity and cognizance is associated with afflictions. If the afflictions were inherent to the mind, they would always be present, and it would be impossible to eliminate them.

The nature of the mind is also said to be clear light because the mind is empty of inherent existence. This is the mind’s natural purity. If the mind existed inherently, the ignorance grasping inherent existence would be a correct knower and would thus be impossible to eliminate. However, the mind and all other phenomena exist dependently. Inherent existence does not exist, and ignorance that grasps it is a wrong consciousness.

Wisdom perceives the emptiness of inherent existence, how phenomena actually exist. Since it realizes the opposite of what ignorance grasps, wisdom has the ability to uproot ignorance. The more we become accustomed to wisdom, the more ignorance and other afflictions diminish, until they cease altogether. The afflictions that have beginninglessly obscured our mind are not abandoned by prayer, by requesting blessings from the Buddha or deities, or by gaining single-pointed concentration. They are eradicated only by wisdom that analyzes and then directly perceives ultimate reality. Because ignorance has an antidote, it can be removed, and liberation is possible. Destroying the afflictions does not destroy the mind itself; the pure nature of the mind remains. This is the meaning of ignorance and afflictions being adventitious.

Each Buddhist tenet system has a slightly different interpretation of liberation and nirvāṇa, but all agree that it is a quality of a mind that has forever separated from the defilements causing saṃsāra through the application of antidotes to those defilements.

When we examine that separation from defilements, we discover it is the ultimate nature of the mind that is free from defilements. This ultimate nature of mind has existed from beginningless time; it exists as long as there is mind. Within the continuum of a sentient being, the ultimate nature of the mind is called buddha nature or buddha potential. When it becomes endowed with the quality of having separated from defilements, it is called nirvāṇa. Therefore, the very basis for nirvāṇa, the emptiness of the mind, is always with us. It’s not something newly created or gained from outside.

Furthermore, the mind’s good qualities can be cultivated limitlessly, transforming our mind into a buddha’s fully awakened mind. Three factors make this possible.

The clear and cognizant nature of the mind is a stable basis for the cultivation of all excellent qualities. The clear-light mind is firm and continual; it cannot be severed. Qualities cannot be cultivated limitlessly on an unstable basis such as the physical body. The more we train in excellent qualities based on this firm basis, the more those qualities will be enhanced limitlessly, until they are fully perfected in the state of buddhahood.

The mind can become habituated to good qualities that are built up cumulatively. Good mental qualities can be built up gradually, without having to begin all over again each time we focus on developing them. A high jumper cannot develop his ability limitlessly—each time the bar is raised, he must cover the same distance as before plus some. However, the energy from cultivating a mental quality today remains so that, if we cultivate that same quality tomorrow, we are able to build upon what we did yesterday. Because we do not need the same degree of energy to get to yesterday’s level again, the same effort will serve to increase that good quality. Of course this requires consistent training on our part; otherwise like an athlete, our spiritual “muscles” will atrophy. But if we practice regularly, our energy can be directed to enhancing the good qualities continuously, until the point where they become so familiar that they are natural and spontaneous.

Good qualities are enhanced, not diminished, by reasoning and wisdom. Constructive attitudes and emotions have a valid support in reasoning and are thus never harmed by the wisdom realizing reality. Compassion, faith, integrity, and all other excellent qualities can be cultivated together with wisdom and are enhanced by wisdom. For this reason, too, they can be cultivated limitlessly.

All Buddhist traditions accept that vast good qualities can be cultivated and defilements can be entirely eliminated from the mind. Each tradition describes the basis upon which this occurs somewhat differently.

In the Pāli scriptures the Buddha identified certain characteristics that reveal spiritual practitioners’ aptitude for liberation. Having modest desire and a sense of contentment signify people are genuine spiritual practitioners aiming for liberation. Indicating their potential to gain attainments, these characteristics should be cultivated daily.

Some sūtras speak of the mind being luminous and this being the basis for mental development. The Buddha says (AN 1:51–52):

This mind, bhikkhus, is luminous, but it is defiled by adventitious defilements. Uninstructed worldlings do not understand this as it really is; therefore for them there is no development of the mind.

This mind, bhikkhus, is luminous, and it is freed from adventitious defilements. Instructed ariyas understand this as it really is; therefore for them there is development of the mind.

The Buddha also says (DN 11:85):

Where consciousness is signless, boundless, all-luminous…

Buddha nature (buddhagotra)33 is spoken of in Sanskrit texts such as the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, Maitreya’s Abhisamayālaṃkāra and Uttaratantra, and Asaṅga’s Bodhisattvabhūmi. It is discussed from three perspectives: the Yogācāra, Madhyamaka, and Tantrayana.

According to Yogācāra, buddha nature is the seed or potency that has existed since beginningless time and has the potential to give rise to the three bodies of a buddha. A conditioned phenomenon, it is the seed of unpolluted exalted wisdom. Saying the buddha nature is a seed fits in well with the Yogācāra system that sees everything as arising due to seeds on the foundation consciousness. When this seed of unpolluted exalted wisdom has not yet been nourished by learning, reflecting, and meditating, it is called the naturally abiding buddha nature. When the same seed has been nourished by learning, reflecting, and meditating on the Dharma, it is called the evolving buddha nature. As the naturally abiding buddha nature, it is a simple seed that has three characteristics: (1) it has existed since beginningless time and has gone from one life to the next uninterruptedly, (2) it is not newly created but naturally abides in us, and (3) it is carried by the foundation consciousness according to Yogācāra Scriptural Proponents and by the mental consciousness according to Yogācāra Reasoning Proponents. Both agree that because sensory consciousnesses are only intermittently present and therefore not a stable basis, they cannot be the buddha nature.

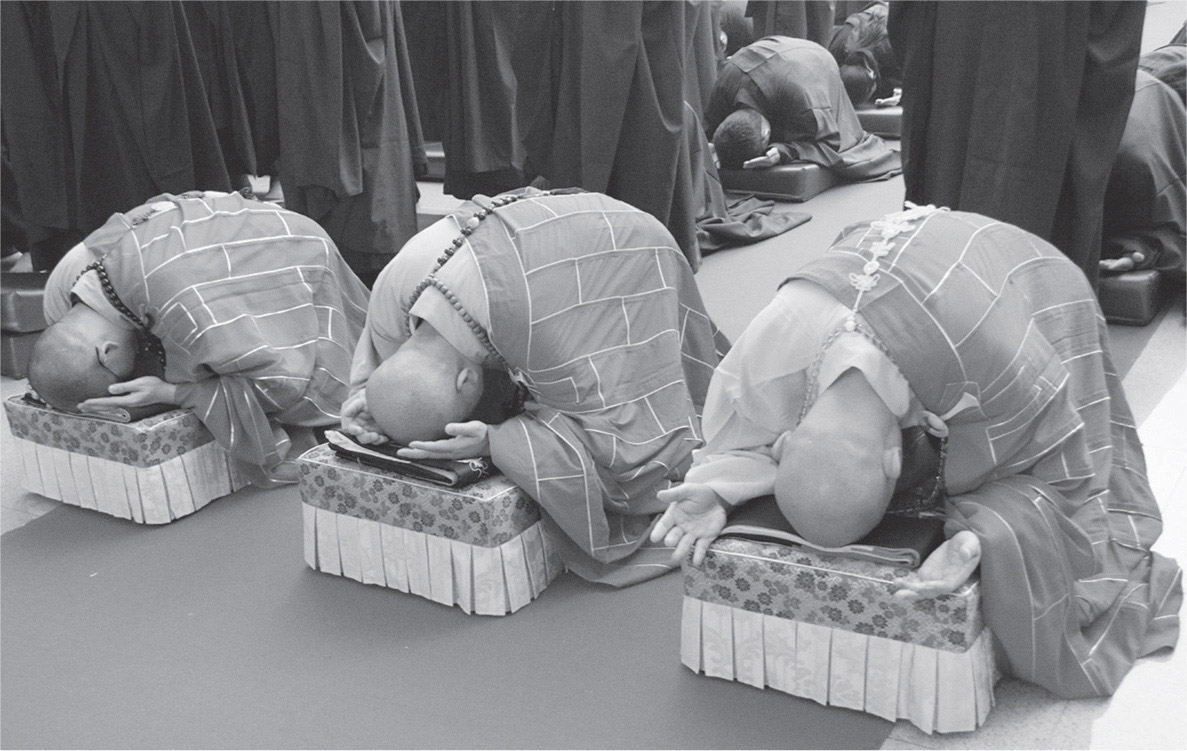

Pureland Marketing

CHINESE MONASTICS BOWING

Later, when the naturally abiding buddha nature has been awakened and transformed by means of learning, reflecting, and meditating, it brings forth the realization of the ārya path and is called the evolving buddha nature. The Yogācāra Scriptural Proponents assert that these seeds or potencies are of three types, according to the three vehicles. Because these seeds are inherently existent, they cannot change into a seed for another vehicle; thus there are three final vehicles. Not every sentient being will become a buddha; some will become Śrāvaka or Pratyekabuddha arhats and abide forever in personal liberation.

Yogācāra Reasoning Proponents and Mādhyamikas both assert one final vehicle and say that all beings will eventually become fully awakened buddhas, including those who enter the śrāvaka and pratyekabuddha vehicles and attain arhatship first.

The Ratnagotravibhāga defines buddha nature as phenomena having the possibility to transform into any of the buddha bodies. From the Madhyamaka perspective, buddha nature principally refers to the emptiness of the mind that is yet to abandon defilements. This empty nature of the mind is beyond time, beyond saṃsāra, and beyond constructive and destructive karma. Neither virtuous nor nonvirtuous, it can act as the basis for both saṃsāra and nirvāṇa. Because buddha nature is simply the mind’s absence of inherent existence and a buddha’s mind also lacks inherent existence, Nāgārjuna notes that the nature of a tathāgata is the nature of sentient beings (MMK 22:16). However, that does not mean sentient beings are already buddhas. For while sentient beings’ minds have defilements, buddhas’ minds do not.

The fact that the nature of the mind is empty does not mean we have already realized emptiness. Only when we realize the empty nature of the mind directly and use that realization to cleanse our minds of defilements will it serve as the basis for āryas’ qualities.

An unconditioned phenomenon that does not depend on causes, the mind’s emptiness of inherent existence is also called natural nirvāṇa. The emptiness of an ordinary being’s mind exists as long as that ordinary being does. When that ordinary being becomes an ārya, the emptiness of that ordinary being’s mind no longer exists, but the emptiness of an ārya’s mind does. These two emptinesses are both the absence of inherent existence, and when perceived by a mind that realizes them directly, there is no difference between them.

As explained above, because the ultimate nature of the mind is empty of inherent existence, the mental defilements obscuring our vision of ultimate reality can be separated from it and removed. These defilements are not embedded in the ultimate nature of the mind.

Insight into the mind’s emptiness, natural nirvāṇa, is the crucial element necessary to overcome all defilements. Cultivating this wisdom initiates the process of undoing the causal chain of the twelve links. By realizing natural nirvāṇa, we will attain the nirvāṇa that is the pacification of mental defilements. This nirvāṇa is the ultimate true cessation, the third truth of the āryas.

As explained in chapter 2, the nature of a buddha’s mind has a twofold purity: its natural stainless purity free from inherent existence, and its purity from having eradicated all adventitious defilements. These two comprise a buddha’s nature dharmakāya. While sentient beings’ minds are empty of inherent existence and their defilements are adventitious, we cannot say their buddha nature is the nature dharmakāya of a buddha with this twofold purity. That is because sentient beings’ minds are still obscured by defilements.

Like Yogācāras, Mādhyamikas also speak of naturally abiding buddha nature and evolving buddha nature, although they describe them differently. These two types of buddha nature exist in all sentient beings, whether or not they are on a path. Naturally abiding buddha nature is the emptiness of a mind that is not freed from defilement and is able to transform into a buddha’s nature dharmakāya. Evolving buddha nature is the seed for the unpolluted mind. It consists of conditioned phenomena that will transform into a buddha’s wisdom dharmakāya. Without this seed in our minds, there would be no way for the awakening activities of the Buddha to enter into us because there would be nothing in our minds that could germinate by coming into contact with the Buddha’s teachings. The evolving buddha nature enables our minds to be affected and transformed by the teachings. The fact that the Buddha taught the Dharma indicates sentient beings have the potential to become buddhas. If we didn’t, his turning the Dharma wheel would have been useless.

The evolving buddha nature includes neutral mental consciousnesses as well as love, compassion, wisdom, bodhicitta, faith, and other virtuous mental states that can be gradually developed as we progressively attain the ten bodhisattva grounds. At the time we become buddhas, our naturally abiding buddha nature will become the nature dharmakāya, and our evolving buddha nature will become the wisdom dharmakāya.

Afflictions cannot be transformed into any of the buddha bodies and do not have buddha nature. Although nonsentient phenomena such as rocks and grass are empty of inherent existence, they do not have buddha nature because they lack mind and cannot generate virtuous mental states.

No matter what realm a sentient being is born into, the naturally abiding buddha nature is always there. It does not decrease or increase. Gold may be buried in the ground for centuries, but uncovering it is always possible. It may be covered with dirt, but it doesn’t become dirt. Although the dirt obscures it, it can be cleansed so that its natural radiance shines. Because the buddha nature exists, we can cleanse it and cultivate all good qualities limitlessly.

According to the unique description of highest yoga tantra, buddha nature is the subtlest mind-wind, whose nature is empty of inherent existence. The subtlest mind is an extremely refined state of mind, also called the innate clear-light mind. The subtlest wind-energy is its mount. The two are inseparable. All sentient beings have this subtlest mind-wind, and its continuity goes on until awakening. It is not a soul or independent essence; it changes moment by moment and is selfless and empty of independent existence. When we die, the coarser levels of mind dissolve into the innate clear-light mind, and when we are reborn, coarser consciousnesses again emerge from the basis of the innate clear-light mind. When these coarser levels of consciousness are present, constructive and destructive thoughts arise and create karma. The result of afflicted thoughts is saṃsāra, the result of virtuous mental states such as renunciation, bodhicitta, and wisdom is the attainment of nirvāṇa. In this way, the innate clear light is the basis for both saṃsāra and nirvāṇa. Sentient beings’ subtlest mind serves as the substantial cause for a buddha’s wisdom dharmakāya, and the subtlest wind-energy is the substantial cause for a buddha’s form body.

In ordinary beings, the subtlest mind-wind manifests only at the time of the clear light of death, when it goes unnoticed. While it is neutral in the case of ordinary beings, special yogic practices can transform it into virtue, thus bringing it into the path to full awakening. Doing this is the heart of highest yoga tantra. Through special tantric practices this subtlest clear-light mind is activated, made blissful, and then used to realize emptiness. Because this mind-wind is so subtle, when it realizes emptiness directly, it becomes a very strong counterforce to eradicate both afflictive and cognitive obscurations. In this way buddhahood may be attained quickly.

From the perspective of Chinese Chan, all sentient beings have the buddha nature that is by nature pure. Here “pure” means it transcends the duality of purity and impurity. When the buddha nature is fully manifested, that being is a buddha. But because of afflictions and defilements—especially ignorance—buddha nature is not presently manifest in sentient beings.

Pure mind and buddha nature refer to the same thing but approach it from different angles. Pure mind indicates that the nature of the mind is not and cannot be polluted by defilements. Buddha nature refers to the aspect of the mind that guarantees our potential and capability to become buddhas. When fully purified, it is called the awakened mind or actual bodhicitta, indicating that when ignorance was present we did not know our pure nature, and now with the removal of ignorance we see and understand it. From the perspective that unawakened beings do not yet recognize the pure nature of their mind, it is said they do not have the bodhi mind (bodhicitta), but from the perspective of the fundamental nature of the mind being pure of adventitious defilements, it is said they have the bodhi mind.

Here bodhicitta refers to the pure mind that can never be tarnished. It is like a pearl that has been covered with mud for thousands of years. Even though it is hidden in mud and its luster cannot be seen, none of its shining beauty has been lost; it is just temporarily obscured. It can be removed from the mud and cleaned so that its beauty is visible to all. Its luster did not decrease by being covered with mud, and its luster did not increase once it was removed from the mud. Similarly, our buddha nature is always pure. Its qualities do not decrease when it is covered with defilements, and they do not increase when the defilements are eradicated.

Bodhicitta is buddha nature. In the Chan tradition the terms true suchness, buddha nature, original nature, ultimate reality, pure nature, and so on have similar meanings. They refer to what cannot be fully known with words. To realize the buddha nature or bodhicitta is to realize that it is uncreated; it does not disappear, it is originally pure.

Peixiu, a Tang-dynasty layman praised by the Huayen and Chan patriarch Zongmi, explains that bodhicitta must be generated from our “true mind”—from the pure aspect of our mind that is part of our buddha nature. It does not arise from identifying with our saṃsāric body or the obscured mind obsessed by sense pleasure and worldly success. Our true body is “perfect and complete, empty and quiescent,” and our true mind is vast in its scope and imbued with intelligence and awareness. The perfect and complete dharmakāya is replete with countless virtuous qualities; it is empty and quiescent in that it goes beyond all forms and characteristics and is forever free of disturbance. The true mind is vast in that it coincides with the dharmadhātu—the sphere of reality. It is imbued with intelligence and awareness because it is focused, penetrating, and clear, investigating illumination. Encompassing great virtuous qualities, it cuts through fallacious thinking, such as the wrong view that things arise from self, other, both, or causelessly. Like a full moon obscured by the clouds of afflictions, its original purity will manifest when the afflictions have been abandoned. As said in the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, “The mind, the Buddha, and beings as well—in these three, there are no distinctions.” This true mind is the same as the essence of the bodhicitta. When we do not see this, we become entwined with false conceptualizations and engage in actions that bind us in saṃsāra.

In the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras popular in China and Tibet, the Buddha explains that each sentient being has a permanent, stable, and enduring tathāgatagarbha, or “buddha essence,” that is a fully developed buddha body complete with the thirty-two signs. While some people take this literally and accept it as a definitive teaching, Mādhyamikas disagree, asking, “If a buddha existed within us in our present state, wouldn’t we be ignorant buddhas? If we were actually buddhas now, what would be the purpose of practicing the path? If we had a permanent, stable, and enduring essence, wouldn’t that contradict the teachings on selflessness and instead resemble the self asserted by non-Buddhists?” These same doubts were expressed by Mahāmati in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra:

The tathāgatagarbha taught [by the Buddha] is said to be clear light in nature, completely pure from the beginning, and to exist, possessing the thirty-two signs, in the bodies of all sentient beings. If, like a precious gem wrapped in a dirty cloth, [the Buddha] expressed that [tathāgatagarbha] wrapped in and dirtied by the cloth of the aggregates, constituents, and sources, overwhelmed by the force of attachment, anger, and ignorance, dirtied with the defilements of thought, and permanent, stable, and enduring, how is this propounded as tathāgatagarbha different from the non-Buddhists propounding a self?

In examining the meaning of the tathāgatagarbha teachings, Mādhyamikas respond to three questions.

What was the Buddha’s final intended meaning when making such a statement? When he spoke of a permanent, stable, and enduring essence in each sentient being, his intended meaning was the emptiness of the mind, the naturally abiding buddha nature, which is permanent, stable, and enduring. Because the mind is empty of inherent existence and the defilements are adventitious, buddhahood is possible.

What was the Buddha’s purpose for teaching this? At present, some people are spiritually immature, and the idea of selflessness and emptiness frightens them. They mistakenly think it means that nothing whatsoever exists and fear that by realizing emptiness they will cease to exist. To calm their fear and gradually lead them to the full and correct realization of emptiness, the Buddha spoke in a way that corresponded with their current ideas, saying there was a permanent, stable, enduring essence, complete with the thirty-two signs.

What logical inconsistencies arise from taking this statement at face value? If this were a literal teaching, there would be no difference between this and the assertions of non-Buddhists who adhere to a permanent, inherently existent self. A permanent essence contradicts the definitive meaning—the emptiness of inherent existence—as expressed in the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, and it is refuted by reasoning.

The emptiness of inherent existence—the ultimate reality and natural purity of the mind—exists in all sentient beings without distinction. In that sense, it is said a buddha is there. But an actual buddha does not exist in sentient beings. While buddhas and sentient beings are similar in that the ultimate nature of their minds is emptiness, that ultimate reality is not the same because one is the ultimate nature of a buddha’s mind—the nature dharmakāya—and the other is the ultimate nature of a defiled mind. If the nature dharmakāya existed in sentient beings, the wisdom dharmakāya, which is one nature with it, would also exist in sentient beings. That would mean that sentient beings would be omniscient, which is not the case! Similarly, if the abandonment of all defilements existed in sentient beings, there would be nothing preventing them from directly perceiving emptiness, and they would have that realization. This, too, is not the case.

If the thirty-two signs were already present in us, it would be contradictory to say that we still need to practice the path to create the causes for them. If someone said that they were already in us in an unmanifest form and just needed to be made manifest, that would resemble the Sāṃkhya notion of arising from self, and Mādhyamikas refute that notion. The sūtra continues with the Buddha’s response:

Mahāmati, my teaching of the tathāgatagarbha is not similar to the propounding of a self by the non-Buddhists. Mahāmati, the tathāgata arhats, the completely perfect buddhas, having indicated the tathāgatagarbha with the meaning of the words emptiness, the limit of complete purity, nirvāṇa, unproduced, signless, wishless, and so forth so that the immature might completely relinquish a state of fear due to the selfless, teach the nonconceptual state, the sphere without appearance.

Here we see that the Buddha skillfully taught different things to different people, according to what was necessary at the moment to lead them on the path. We also learn that we must think deeply about the teachings, employ reasoning, and read widely in the sūtras and commentaries to discern their definitive meaning. By doing so, we will reach the correct understanding of the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras, which contain profound teachings hinting at the existence of the fundamental innate clear-light mind explained in tantra.

The purpose of learning about buddha nature and tathāgatagarbha is to understand that the mind is not intrinsically flawed and can be perfected, and that aspects of the mind already exist that allow it to be purified and perfected. Understanding this will give us great confidence and energy to practice the methods to purify and perfect this mind of ours so that it will become the mind of a fully awakened buddha.