THE SITE OF TUSKEGEE INSTITUTE WHEN IT WAS FIRST BOUGHT

Two of the buildings are still in use as dormitories

II. BUILDING A SCHOOL AROUND A PROBLEM

ONE OF THE first questions that I had to answer for myself after beginning my work at Tuskegee was how I was to deal with public opinion on the race question.

It may seem strange that a man who had started out with the humble purpose of establishing a little Negro industrial school in a small Southern country town should find himself, to any great extent, either helped or hindered in his work by what the general public was thinking and saying about any of the large social or educational problems of the day. But such was the case at that time in Alabama; and so it was that I had not gone very far in my work before I found myself trying to formulate clear and definite answers to some very fundamental questions.

The questions came to me in this way: Coloured people wanted to know why I proposed to teach their children to work. They said that they and their parents had been compelled to work for two hundred and fifty years, and now they wanted their children to go to school so that they might be free and live like the white folks—without working. That was the way in which the average coloured man looked at the matter.

Some of the Southern white people, on the contrary, were opposed to any kind of education of the Negro. Others inquired whether I was merely going to train preachers and teachers, or whether I proposed to furnish them with trained servants.

Some of the people in the North understood that I proposed to train the Negro to be a mere “hewer of wood and drawer of water,” and feared that my school would make no effort to prepare him to take his place in the community as a man and a citizen.

Of course all these different views about the kind of education that the Negro ought or ought not to have were deeply tinged with racial and sectional feelings. The rule of the “carpet-bag” government had just come to an end in Alabama. The masses of the white people were very bitter against the Negroes as a result of the excitement and agitation of the Reconstruction period.

On the other hand, the coloured people—who had recently lost, to a very large extent, their place in the politics of the state—were greatly discouraged and disheartened. Many of them feared that they were going to be drawn back into slavery. At this time also there was still a great deal of bitterness between the North and the South in regard to anything that concerned political matters.

I found myself, as it were, at the angle where these opposing forces met. I saw that, in carrying out the work I had planned, I was likely to be opposed or criticised at some point by each of these parties. On the other hand, I saw just as clearly that in order to succeed I must in some way secure the support and sympathy of each of them. I knew, for example, that the South was poor and the North was rich. I knew that Northern people believed, as the South at that time did not believe, in the power of education to inspire, to uplift, and to regenerate the masses of the people. I knew that the North was eager to go forward and complete, with the aid of education, the work of liberation which had been begun with the sword, and that Northern people would be willing and glad to give their support to any school or other agency that proposed to do this work in a really fundamental way.

THE SITE OF TUSKEGEE INSTITUTE WHEN IT WAS FIRST BOUGHT

Two of the buildings are still in use as dormitories

It was, at the same time, plain to me that no effort put forth in behalf of the members of my own race who were in the South was going to succeed unless it finally won the sympathy and support of the best white people in the South. I knew also—what many Northern people did not know or understand—that however much they might doubt the wisdom of educating the Negro, deep down in their hearts the Southern white people had a feeling of gratitude toward the Negro race; and I was convinced that in the long run any sound and sincere effort that was made to help the Negro was going to have the Southern white man’s support.

Finally, I had faith in the good common-sense of the masses of my own race. I felt confident that, if I were actually on the right track in the kind of education that I proposed to give them and at the same time remained honest and sincere in all my dealings with them, I was bound to win their support, not only for the school that I had started, but for all that I had in my mind to do for them.

Still it was often a puzzling and a trying problem to determine how best to win and hold the respect of all three of these classes of people, each of which looked with such different eyes and from such widely different points of view at what I was attempting to do. The temptation which presented itself to me in my dealings with these three classes of people was to show each group the side of the subject that it would be most willing to look at, and, at the same time, to keep silent about those matters in regard to which they were likely to differ with me. There was the temptation to say to the white man the thing that the white man wanted to hear; to say to the coloured man the thing that he wanted to hear; to say one thing in the North and another in the South.

Perhaps I should have yielded to this temptation if I had not perceived that in the long run I should be found out, and that if I hoped to do anything of lasting value for my own people or for the South I must first get down to bedrock.

There is a story of an old coloured minister, which I am fond of telling, that illustrates what I mean. The old fellow was trying to explain to a Sunday-school class how it was and why it was that Pharaoh and his party were drowned when they were trying to cross the Red Sea, and how it was and why it was that the Children of Israel crossed over dry-shod. He explained it in this wise:

“When the first party came along it was early in the morning and the ice was hard and thick, and the first party had no trouble in crossing over on the ice; but when Pharaoh and his party came along the sun was shining on the ice, and when they got on the ice it broke, and they went in and got drowned.”

Now there happened to be in this class a young coloured man who had had considerable schooling, and this young fellow turned to the old minister and said:

“Now, Mr. Minister, I do not understand that kind of explanation. I have been going to school and have been studying all these conditions, and my geography teaches me that ice does not freeze within a certain distance of the equator.”

The old minister replied: “Now, I’se been expecting something just like this. There’s always some fellow ready to spile all the theology. The time I’se talkin’ about was before they had any jogerphies or ’quaters either.”

Now this old man, in his plain and simple way, was trying to brush aside all artificiality and to get down to bedrock. So it was with me. There have always been a number of educated and clever persons among my race who are able to make plausible and fine-sounding statements about all the different phases of the Negro problem, but I saw clearly that I should have to follow the example of the old preacher and start on a solid basis in order to succeed in the work that I had undertaken. So, after thinking the matter all out as I have described, I made up my mind definitely on one or two fundamental points. I determined:

First, that I should at all times be perfectly frank and honest in dealing with each of the three classes of people that I have mentioned;

Second, that I should not depend on any “short-cuts” or expedients merely for the sake of gaining temporary popularity or advantage, whether for the time being such action brought me popularity or the reverse. With these two points clear before me as my creed, I began going forward.

One thing which gave me faith at the outset, and increased my confidence as I went on, was the insight which I early gained into the actual relations of the races in the South. I observed, in the first place, that as a result of two hundred and fifty years of slavery the two races had become bound together in intimate ways that people outside of the South could not understand, and of which the white people and coloured people themselves were perhaps not fully conscious. More than that, I perceived that the two races needed each other and that for many years to come no other labouring class of people would be able to fill the place occupied by the Negro in the life of the Southern white man.

I saw also one change that had been brought about as a result of freedom, a change which many Southern white men had, it seemed to me, failed to see. As long as slavery existed, the white man, for his own protection and in order to keep the Negro contented with his condition of servitude, was compelled to keep him in ignorance. In freedom, however, just the reverse condition exists. Now the white man is not only free to assist the Negro in his effort to rise, but he has every motive of self-interest to do so, since to uplift and educate the Negro would reduce the number of paupers and criminals of the race and increase the number and efficiency of its skilled labourers.

Clear ideas did not come into my mind on this subject at once. It was only gradually that I gained the notion that there had been two races in slavery; that both were now engaged in a struggle to adjust themselves to the new conditions; that the progress of each meant the advancement of the other; and that anything that I attempted to do for the members of my own race would be of no real value to them unless it was of equal value to the members of the white race by whom they were surrounded.

As this thought got hold in my mind and I began to see further into the nature of the task that I had undertaken to perform, much of the political agitation and controversy that divided the North from the South, the black man from the white, began to look unreal and artificial to me. It seemed as if the people who carried on political campaigns were engaged to a very large extent in a battle with shadows, and that these shadows represented the prejudices and animosities of a period that was now past.

On the contrary, the more I thought about it, the more it seemed to me that the kind of work that I had undertaken to do was a very real sort of thing. Moreover, it was a kind of work which tended not to divide, but to unite, all the opposing elements and forces, because it was a work of construction.

Having gone thus far, I began to consider seriously how I should proceed to gain the sympathy of each of the three groups that I have mentioned for the work that I had in hand.

I determined, first of all, that as far as possible I would try to gain the active support and cooperation in all that I undertook, of the masses of my own race. With this in view, before I began my work at Tuskegee, I spent several weeks travelling about among the rural communities of Macon County, of which Tuskegee is the county seat. During all this time I had an opportunity to meet and talk individually with a large number of people representing the rural classes, which constitute 80 per cent. of the Negro population in the South. I slept in their cabins, ate their food, talked to them in their churches, and discussed with them in their own homes their difficulties and their needs. In this way I gained a kind of knowledge which has been of great value to me in all my work since.

As years went on, I extended these visits to the adjoining counties and adjoining states. Then, as the school at Tuskegee became better known, I took advantage of the invitations that came to me to visit more distant parts of the country, where I had an opportunity to learn still more about the actual life of the people and the nature of the difficulties with which they were struggling.

In all this, my purpose was to get acquainted with the masses of the people—to gain their confidence so that I might work with them and for them.

In the course of travel and observation I became more and more impressed with the influence that the organizations which coloured people have formed among themselves exert upon the masses of people.

The average man outside of the Negro race is likely to assume that the ten millions of coloured people in this country are a mere disorganized and heterogeneous collection of individuals, herded together under one statistical label, without head or tail, and with no conscious common purpose. This is far from true. There are certain common interests that are peculiar to all Negroes, certain channels through which it is possible to touch and influence the whole people. In my study of the race in what I may call its organized capacity, I soon learned that the most influential organization among Negroes is the Negro church. I question whether or not there is a group of ten millions of people anywhere, not excepting the Catholics, that can be so readily reached and influenced through their church organizations as the ten millions of Negroes in the United States. Of these millions of black people there is only a very small percentage that does not have formal or informal connection with some church. The principal church groups are: Baptists, African Methodists, African Methodist Episcopal Zionists, and Coloured Methodists, to which I might add about a dozen smaller denominations.

I began my work of getting the support of these organizations by speaking (or lecturing, as they are accustomed to describe it) to the coloured people in the little churches in the country surrounding the school at Tuskegee. When later I extended my journeys into other and more distant parts of the country, I began to get into touch with the leaders in the church and to learn something about the kind and extent of influence which these men exercise through the churches over the masses of the Negro people.

It has always been a great pleasure to me to meet and to talk in a plain, straightforward way with the common people of my own race wherever I have been able to meet them. But it is in the Negro churches that I have had my best opportunities for meeting and getting acquainted with them.

It has been my privilege to attend service in Trinity Church, Boston, where I heard Phillips Brooks. I have attended service in the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York, where I heard the late Dr. John Hall. I have attended service in Westminster Abbey, in London. I have visited some of the great cathedrals in Europe when service was being held. But not any of these services have had for me the real interest that certain services among my own people have had. Let me describe the type of the service that I have enjoyed more than any other in all my experience in attending church, whether in America or Europe.

In Macon County, Ala., where I live, the coloured people have a kind of church-service that is called an “all-day meeting.” The ideal season for such meeting is about the middle of May. The church-house that I have in mind is located about ten miles from town. To get the most out of the “all-day meeting” one should make an early start, say eight o’clock. During the drive one drinks in the fresh fragrance of forests and wild flowers. The church building is located near a stream of water, not far from a large, cool, spring, and in the midst of a grove or primitive forest. Here the coloured people begin to come together by nine or ten o’clock in the morning. Some of them walk; most of them drive. A large number come in buggies, but many use the more primitive wagons or carts, drawn by mules, horses, or oxen. In these conveyances a whole family, from the youngest to the eldest, make the journey together. All bring baskets of food, for the “all-day meeting” is a kind of Sunday picnic or festival. Preaching, preceded by much singing, begins at about eleven o’clock. If the building is not large enough, the services are held out under the trees. Sometimes there is but one sermon; sometimes there are two or three sermons, if visiting ministers are present. The sermon over, there is more plantation singing. A collection is taken—sometimes two collections—then comes recess for dinner and recreation.

Sometimes I have seen at these “all-day meetings” as many as three thousand people present. No one goes away hungry. Large baskets, filled with the most tempting spring chicken or fresh pork, fresh vegetables, and all kinds of pies and cakes, are then opened. The people scatter in groups. Sheets or table-cloths are spread on the grass under a tree near the stream. Here old acquaintances are renewed; relatives meet members of the family whom they have not seen for months. Strangers, visitors, every one must be invited by some one else to dinner. Kneeling on the fresh grass or on broken branches of trees surrounding the food, dinner is eaten. The animals are fed and watered, and then at about three o’clock there is an other sermon or two, with plenty of singing thrown in; then another collection, or perhaps two. In between these sermons I am invited to speak, and am very glad to accept the invitation. About five o’clock the benediction is pronounced and the thousands quietly scatter to their homes with many good-bys and well-wishes. This, as I have said, is the kind of church-service that I like best. In the opportunities which I have to speak to such gatherings I feel that I have done some of my best work.

In carrying out the policy which I formed early, of making use of every opportunity to speak to the masses of the people, I have not only visited country churches and spoken at such “all-day meetings” as I have just described, but for years I have made it a practice to attend, whenever it has been possible for me to do so, every important ministers’ meeting. I have also made it a practice to visit town and city churches and in this way to get acquainted with the ministers and meet the people.

During my many and long campaigns in the North, for the purpose of getting money to carry on Tuskegee Institute, it has been a great pleasure and satisfaction to me, after I have spoken in some white church or hall or at some banquet, to go directly to some coloured church for a heart-to-heart talk with my own people. The deep interest that they have shown in my work and the warmth and enthusiasm with which coloured people invariably respond to any one who talks to them frankly and sincerely in regard to matters that concern the welfare of the race, make it a pleasure to speak to them.

Many times on these trips to the North it has happened that coloured audiences have waited until ten or eleven o’clock at night for my coming. This does not mean that coloured people may not attend the other meetings which I address, but means simply that they prefer in most cases to have me speak to them alone. When at last I have been able to reach the church or the hall where the audience was gathered, it has been such a pleasure to meet them that I have often found myself standing on my feet until after twelve o’clock. No one thing has given me more faith in the future of the race than the fact that Negro audiences will sit for two hours or more and listen with the utmost attention to a serious discussion of any subject that has to do with their interest as a people. This is just as true of the unlettered masses as it is of the more highly educated few.

Not long ago, for example, I spoke to a large audience in the Chamber of Commerce in Cleveland, Ohio. This audience was composed for the most part of white people, and the meeting continued rather late into the night. Immediately after this meeting I was driven to the largest coloured church in Cleveland, where I found an audience of something like twenty-five hundred coloured people waiting patiently for my appearance. The church building was crowded, and many of those present, I was told, had been waiting for two or three hours.

As I entered the building an unusual scene presented itself. Each member of the audience had been provided with a little American flag, and as I appeared upon the platform, the whole audience rose to its feet and began waving these flags. The reader can, perhaps, imagine the picture of twenty-five hundred enthusiastic people each of whom is wildly waving a flag. The scene was so animated and so unexpected that it made an impression on me that I shall never forget. For an hour and a half I spoke to this audience, and, although the building was crowded until there was apparently not an inch of standing room in it, scarcely a single person left the church during this time.

Another way in which I have gained the confidence and support of the millions of my race has been in meeting the religious leaders in their various state and national gatherings. For example, every year, for a number of years past, I have been invited to deliver an address before the National Coloured Baptist Convention, which brings together four or five thousand religious leaders from all parts of the United States. In a similar way I meet, once in four years, the leaders in the various branches of the Methodist Church during their general conferences.

Invitations to address the different secret societies in their national gatherings frequently come to me also. Next to the church, I think it is safe to say that the secret societies or beneficial orders bring together greater numbers of coloured people and exercise a larger influence upon the race than any other kind of organization. One can scarcely shake hands with a coloured man without receiving some kind of grip which identifies him as a member of one or another of these many organizations.

I am reminded, in speaking of these secret societies, of an occasion at Little Rock, Ark., when, without meaning to do so, I placed my friends there in a very awkward position. It had been pretty widely advertised for some weeks before that I was to visit the city. Among the plans decided upon for my reception was a parade, in which all the secret and beneficial societies in Little Rock were to take part. Much was expected of this parade, because secret societies are numerous in Little Rock, and the occasions when they can all turn out together are rare.

A few days before I reached that city some one began to make inquiry as to which one of these orders I belonged to. When it finally became known among the rank and file that I was not a member of any of them, the committee which was preparing for the parade lost a great deal of its enthusiasm, and a sort of gloom settled down over the whole proceeding. The leading men told me that they found it quite a difficult task after that to make the people understand why they were asked to turn out to honour a person who was not a member of any of their organizations. Besides, it seemed unnatural that a Negro should not belong to some kind of order. Somehow or other, however, matters were finally straightened out; all the organizations turned out, and a most successful reception was the result.

Another agency which exercises tremendous power among Negroes is the Negro press. Few if any persons outside of the Negro race understand the power and influence of the Negro newspaper. In all, there are about two hundred newspapers published by coloured men at different points in the United States. Many of them have only a small circulation and are, therefore, having a hard struggle for existence; but they are read in their local communities. Others have built up a national circulation and are conducted with energy and intelligence. With the exception of about three, these two hundred papers have stood loyally by me in all my plans and policies to uplift the race. I have called upon them freely to aid me in making known my plans and ideas, and they have always responded in a most generous fashion to all the demands that I have made upon them.

It has been suggested to me at different times that I should purchase a Negro newspaper in order that I might have an “organ” to make known my views on matters concerning the policies and interests of the race. Certain persons have suggested also that I pay money to certain of these papers in order to make sure that they support my views.

I confess that there have frequently been times when it seemed that the easiest way to combat some statement that I knew to be false, or to correct some impression which seemed to me peculiarly injurious, would be to have a paper of my own or to pay for the privilege of setting forth my own views in the editorial columns of some paper which I did not own.

I am convinced, however, that either of these two courses would have proved fatal. The minute it should become known—and it would be known—that I owned an “organ,” the other papers would cease to support me as they now do. If I should attempt to use money with some papers, I should soon have to use it with all. If I should pay for the support of newspapers once, I should have to keep on paying all the time. Very soon I should have around me, if I should succeed in bribing them, merely a lot of hired men and no sincere and earnest supporters. Although I might gain for myself some apparent and temporary advantage in this way, I should destroy the value and influence of the very papers that support me. I say this because if I should attempt to hire men to write what they do not themselves believe, or only half believe, the articles or editorials they write would cease to have the true ring; and when they cease to have the true ring, they will exert little or no influence.

So, when I have encountered opposition or criticism in the press, I have preferred to meet it squarely. Frequently I have been able to profit by these criticisms of the newspapers. At other times, when I have felt that I was right and that those who criticised me were wrong, I have preferred to wait and let the results show. Thus, even when we differed with one another on minor points, I have usually succeeded in gaining the confidence and support of the editors of the different papers in regard to those matters and policies which seemed to me really important.

In travelling throughout the United States I have met the Negro editors. Many of them have been to Tuskegee. It has taken me twenty years to get acquainted with them and to know them intimately. In dealing with these men I have not found it necessary to hold them at arm’s-length. On the contrary, I am in the habit of speaking with them frankly and openly in regard to my plans. A number of the men who own and edit Negro newspapers are graduates or former students of the Tuskegee Institute. I go into their offices and I go to their homes. We know one another; they are my friends, and I am their friend.

In dealing with newspaper people, whether they are white or black, there is no way of getting their sympathy and support like that of actually knowing the individual men, of meeting and talking with them frequently and frankly, and of keeping them in touch with everything you do or intend to do. Money cannot purchase or control this kind of friendship.

Whenever I am in a town or city where Negro newspapers are published, I make it a point to see the editors, to go to their offices, or to invite them to visit Tuskegee. Thus we keep in close, constant, and sympathetic touch with one another. When these papers write editorials endorsing any project that I am interested in, the editors speak with authority and with intelligence because of our close personal relations. There is no more generous and helpful class of men among the Negro race in America to-day than the owners and editors of Negro newspapers.

Many time I have been asked how it is that I have secured the confidence and good wishes of so large a number of the white people of the South.

My answer in brief is that I have tried to be perfectly frank and straightforward at all times in my relations with them. Sometimes they have opposed my actions, sometimes they have not, but I have never tried to deceive them. There is no people in the world which more quickly recognizes and appreciates the qualities of frankness and sincerity, whether they are exhibited in a friend or in an opponent, in a white man or in a black man, than the white people of the South.

In my experience in dealing with men of my race I have found that there is a class that has gained a good deal of fleeting popularity for possessing what was supposed to be courage in cursing and abusing all classes of Southern white people on all possible occasions. But, as I have watched the careers of this class of Negroes, in practically every case their popularity and influence with the masses of coloured people have not been lasting. There are few races of people the masses of whom are endowed with more commonsense than the Negro, and in the long run these common people see things and men pretty much as they are.

On the other hand, there have always been in every Southern community a certain number of coloured men who have sought to gain the friendship of the white people around them in ways that were more or less dishonest. For a number of years after the close of the Civil War, for example, it was natural that practically all the Negroes should be Republicans in politics. There were, however, in nearly every community in the South, one or two coloured men who posed as Democrats. They thought that by pretending to favour the Democratic party they might make themselves popular with their white neighbours and thus gain some temporary advantage. In the majority of cases the white people saw through their pretences and did not have the respect for them that they had for the Negro who honestly voted with the party to which he felt that he belonged.

I remember hearing a prominent white Democrat remark not long ago that in the old days whenever a Negro Democrat entered his office he always took a tight grasp upon his pocket-book. I mention these facts because I am certain that wherever I have gained the confidence of the Southern people I have done so, not by opposing them and not by truckling to them, but by acting in a straightforward manner, always seeking their good-will, but never seeking it upon false pretences.

I have made it a rule to talk to the Southern white people concerning what I might call their shortcomings toward the Negro rather than talk about them. In the last analysis, however, I have succeeded in getting the sympathy and support of so large a number of Southern white people because I have tried to recognize and to face conditions as they actually are, and have honestly tried to work with the best white people in the South to bring about a better condition.

From the first I have tried to secure the confidence and goodwill of every white citizen in my own county. My experience teaches me that if a man has little or no influence with those by whose side he lives, as a rule there is something wrong with him. The best way to influence the Southern white man in your community, I have found, is to convince him that you are of value to that community. For example, if you are a teacher, the best way to get the influence of your white neighbours is to convince them that you are teaching something that will make the pupils that you educate able to do something better and more useful than they would otherwise be able to do; to show, in other words, that the education which they get adds something of value to the community.

In my own case, I have attempted from the beginning to let every white citizen in my own town see that I am as much interested in the common, every-day affairs of life as himself. I tried to let them see that the presence of Tuskegee Institute in the community means better farms and gardens, good housekeeping, good schools, law and order. As soon as the average white man is convinced that the education of the Negro makes of him a citizen who is not always “up in the air,” but one who can apply his education to the things in which every citizen is interested, much of opposition, doubt, or indifference to Negro education will disappear.

During all the years that I have lived in Macon County, Ala., I have never had the slightest trouble in either registering or casting my vote at any election. Every white person in the county knows that I am going to vote in a way that will help the county in which I live.

Many nights I have been up with the sheriff of my county, in consultation concerning law and order, seeking to assist him in getting hold of and freeing the community of criminals. More than that, Tuskegee Institute has constantly sought, directly and indirectly, to impress upon the twenty-five or thirty thousand coloured people in the surrounding county the importance of cooperating with the officers of the law in the detection and apprehension of criminals. The result is that we have one of the most orderly communities in the state. I do not believe that there is any county in the state, for example, where the prohibition laws are so strictly enforced as in Macon County, in spite of the fact that the Negroes in this county so largely outnumber the whites.

Whatever influence I have gained with the Northern white people has come about from the fact, I think, that they feel that I have tried to use their gifts honestly and in a manner to bring about real and lasting results. I learned long ago that in education as in other things nothing but honest work lasts; fraud and sham are bound to be detected in the end. I have learned, on the other hand, that if one does a good, honest job, even though it may be done in the middle of the night when no eyes see but one’s own, the results will just as surely come to light.

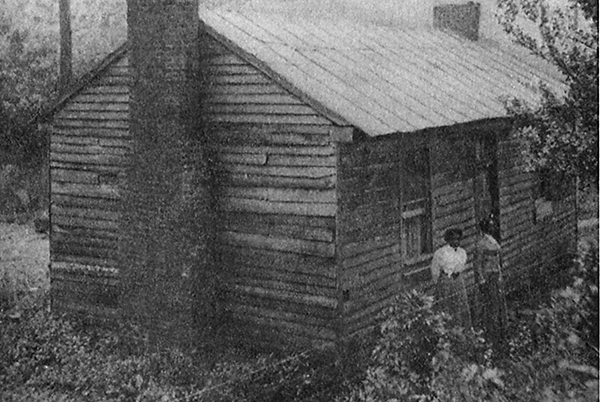

THE HOUSE IN MALDEN, W.VA., IN WHICH MR. WASHINGTON LIVED WHEN HE BEGAN TEACHING

My experience has taught me, for example, that if there is a filthy basement or a dirty closet anywhere in the remotest part of the school grounds it will be discovered. On the other hand, if every basement or every closet—no matter how remote from the centre of the school activities—is kept clean, some one will find it and commend the care and the thoughtfulness that kept it clean.

It has always been my policy to make visitors to Tuskegee feel that they are seeing more than they expected to see. When a person has contributed, say, $20,000 for the erection of a building, I have tried to provide a larger building, a better building, than the donor expected to see. This I have found can be brought about only by keeping one’s eyes constantly on all the small details. I shall never forget a remark made to me by Mr. John D. Rockefeller when I was spending an evening at his house. It was to this effect: “Always be master of the details of your work; never have too many loose outer edges or fringes.”

Then, in dealing with Northern people, I have always let them know that I did not want to get away from my own race; that I was just as proud of being a Negro as they were of being white people. No one can see through a sham more quickly, whether it be in speech or in dress, than the hard-headed Northern business man.

I once knew a fine young coloured man who nearly ruined himself by pretending to be something that he was not. This young man was sent to England for several months of study. When he returned he seemed to have forgotten how to talk. He tried to ape the English accent, the English dress, the English walk. I was amused to notice sometimes, when he was off his guard, how he got his English pronunciation mixed with the ordinary American accent which he had used all of his life. So one day I quietly called him aside and said to him: “My friend, you are ruining yourself. Just drop all those frills and be yourself.” I am glad to say that he had sense enough to take the advice in the right spirit, and from that time on he was a different man.

The most difficult and trying of the classes of persons with which I am brought in contact is the coloured man or woman who is ashamed of his or her colour, ashamed of his or her race and, because of this fact, is always in a bad temper. I have had opportunities, such as few coloured men have had, of meeting and getting acquainted with many of the best white people, North and South. This has never led me to desire to get away from my own people. On the contrary, I have always returned to my own people and my own work with renewed interest.

I have never at any time asked or expected that any one, in dealing with me, should overlook or forget that I am a Negro. On the contrary, I have always recognized that, when any special honour was conferred upon me, it was conferred not in spite of my being a Negro, but because I am a Negro, and because I have persistently identified myself with every interest and with every phase of the life of my own people.

Looking back over the twenty-five and more years that have passed since that time, I realize, as I did not at that time, how the better part of my education—the education that I got after leaving school—has been in the effort to work out those problems in a way that would gain the interest and the sympathy of all three of the classes directly concerned—the Southern white man, the Northern white man, and the Negro.

In order to gain consideration from these three classes for what I was trying to do I have had to enter sympathetically into the three different points of view entertained by those three classes; I have had to consider in detail how the work that I was trying to do was going to affect the interests of all three. To do this, and at the same time continue to deal frankly and honestly with each class, has been indeed a difficult and at times a puzzling task. It has not always been easy to stick to my work and keep myself free from the distracting influences of narrow and factional points of view; but, looking back on it all after a quarter of a century, I can see that it has been worth what it cost.