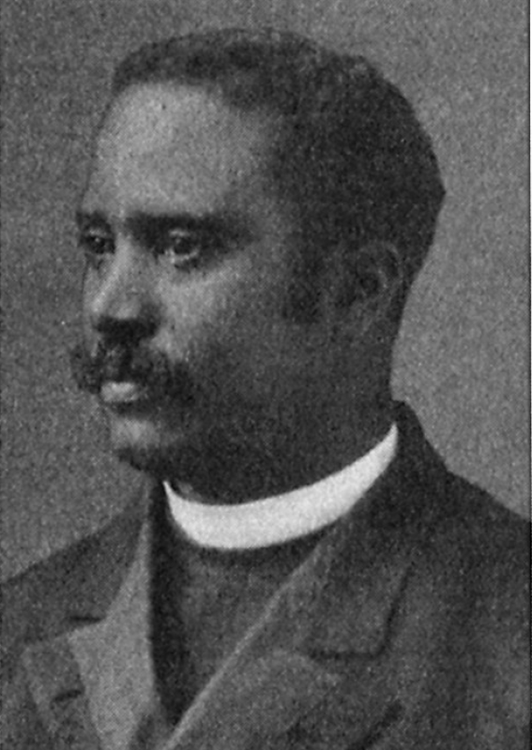

RUFUS HERRON OF CAMP HILL, ALA.

“If there is a white man, North or South, that has more love for his community or his country than Rufus Herron, it has not been my good fortune to meet him.”

IX. WHAT I HAVE LEARNED FROM BLACK MEN

NO SINGLE QUESTION is more often asked me than this: “Has the pure blooded black man the same ability or the same worth as those of mixed blood?”

It has been my good fortune to have had a wide acquaintance with black as well as brown and even white Negroes. The race to which I belong permits me to meet and know people of all colours and conditions. There is no race or people who have within themselves the choice of so large a variety of colours and conditions as is true of the American Negro. The Japanese, as a rule, can know intimately human nature in only one hue, namely, yellow. The white man, as a rule, does not get intimately acquainted with any other than white men. The Negro, however, has a chance to know them all, because within his own race and among his own acquaintances he has friends, perhaps even relatives, of every colour in which mankind has been painted.

Perhaps I can answer the question as to the relative value of the pure Negro and the mixed blood in no better way than by telling what I know concerning, and what I have learned from, some four or five men of the purest blood and the darkest skins of any human beings I happen to know—men to whom I am indebted for many things, but most of all for what they have done for me in teaching me to value all men at their real worth regardless of race or colour.

Among those black men whom I have known, the one who comes first to my mind is Charles Banks, of Mound Bayou, Miss., banker, cotton broker, planter, real-estate dealer, head of a hundred-thousand-dollar corporation which is erecting a cottonseed oil mill, the first ever built and controlled by Negro enterprise and Negro capital, and, finally, leading citizen of the little Negro town of Mound Bayou.

I first met Charles Banks in Boston. As I remember, he came in company with Hon. Isaiah T. Montgomery, the founder of Mound Bayou, to represent, at the first meeting of the National Negro Business League in 1900, the first and at that time the only town in the United States founded, inhabited, and governed exclusively by Negroes. He was then, as he is to-day, a tall, big-bodied man, with a shiny round head, quick, snapping eyes, and a surprisingly swift and quiet way of reaching out and getting anything he happens to want. I never appreciated what a big man Banks was until I began to notice the swift and unerring way in which he reached out his long arm to pick up, perhaps a pin, or to get hold of the buttonhole and of the attention of an acquaintance. He seemed to be able to reach without apparent effort anything he wanted, and I soon found there was a certain fascination in watching him move.

I have been watching Banks reach for things that he wanted, and get them, ever since that time. I have been watching him do things, watching him grow, and as I have studied him more closely my admiration for this big, quiet, graceful giant has steadily increased. One thing that has always impressed itself upon me in regard to Mr. Banks is the fact that he never claims credit for doing anything that he can give credit to other people for doing. He has never made any effort to make himself prominent. He simply prefers to get a job done and, if he can use other people and give them credit for doing the work, he is happy to do so.

At the present time Charles Banks is not, by any means, the wealthiest, but I think I am safe in saying that he is the most influential, Negro business man in the United States. He is the leading Negro banker in Mississippi, where there are eleven Negro banks, and he is secretary and treasurer of the largest benefit association in that state, namely, that attached to the Masonic order, which paid death claims in 1910 to the amount of one hundred and ninety-five thousand dollars and had a cash balance of eighty thousand dollars. He organized and has been the moving spirit in the state organization of the Business League in Mississippi and has been for a number of years the vice-president of the National Negro Business League.

Charles Banks is, however, more than a successful business man. He is a leader of his race and a broad-minded and public-spirited citizen. Although he holds no public office, and, so far as I know, has no desire to do so, there are, in my opinion, few men, either white or black, in Mississippi today who are performing, directly or indirectly, a more important service to their state than Charles Banks.

Without referring to the influence that he has been able to exercise in other directions, I want to say a word about the work he is doing at Mound Bayou for the Negro people of the Yazoo Delta, where, in seventeen counties, the blacks represent from seventy-five to ninety-four per cent. of the whole population.

As I look at it, Mound Bayou is not merely a town; it is at the same time and in a very real sense of that word, a school. It is not only a place where a Negro may get inspiration, by seeing what other members of his race have accomplished, but a place, also, where he has an opportunity to learn some of the fundamental duties and responsibilities of social and civic life.

Negroes have here, for example, an opportunity, which they do not have to the same degree elsewhere, either in the North or in the South, of entering simply and naturally into all the phases and problems of community life. They are the farmers, the business men, bankers, teachers, preachers. The mayor, the constable, the aldermen, the town marshal, even the station agent, are Negroes.

Black men cleared the land, built the houses, and founded the town. Year by year, as the colony has grown in population, these pioneers have had to face, one after another, all the fundamental problems of civilization. The town is still growing, and as it grows, new and more complicated problems arise. Perhaps the most difficult problem the leaders of the community have to face now is that of founding a school, or a system of schools, in which the younger generation may be able to get some of the kind of knowledge which these pioneers gained in the work of building up and establishing the community.

During the twenty years this town has been in existence it has always had the sympathetic support of people in neighbouring white communities. One reason for this is that the men who have been back of it were born and bred in the Delta, and they know both the land and the people.

Charles Banks was born and raised in Clarksdale, a few miles above Mound Bayou, where he and his brother were for several years engaged in business. It was his good fortune, as has been the case with many other successful Negroes, to come under the influence, when he was a child, of one of the best white families in the city in which he was born. I have several times heard Mr. Banks tell of his early life in Clarksdale and of the warm friends he had made among the best white people in that city.

It happened that his mother was cook for a prominent white family in Clarksdale. In this way be became in a sort of a way attached to the family. It was through the influence of this family, if I remember rightly, that he was sent to Rust University, at Holly Springs, to get his education.

In 1900 Mr. Banks, because of his wide knowledge of local conditions in that part of the country, was appointed supervisor of the census for the Third district of Mississippi. In speaking to me of this matter Mr. Banks said that every white man in town endorsed his application for appointment.

Since he has been in Mound Bayou, Mr. Banks has greatly widened his business connections. The Bank of Mound Bayou now counts among its correspondents banks in Vicksburg, Memphis, and Louisville, together with the National Bank of Commerce of St. Louis and the National Reserve Bank of the City of New York. One of the officers of the former institution, Mr. Eugene Snowden, in a recent letter to me, referring to this and another Negro bank, writes: “It has been my pleasure to lend them $30,000 a year and their business has been handled to my entire satisfaction.”

Some years ago, in the course of one of my educational campaigns, I visited Mound Bayou, among other places in Mississippi. Among other persons I met the sheriff of Bolivar County, in which Mound Bayou is situated. Without any suggestion or prompting on my part, he told me that Mound Bayou was one of the most orderly—in fact, I believe he said the most orderly—town in the Delta. A few years ago a newspaper man from Memphis visited the town for the purpose of writing an article about it. What he saw there set him to speculating, and among other things he said:

Will the Negro as a race work out his own salvation along Mound Bayou lines? Who knows? These have worked out for themselves a better local government than any superior people has ever done for them in freedom. But it is a generally accepted principle in political economy that any homogeneous people will in time do this. These people have their local government, but it is consonance with the county, state, and national governments and international conventions, all in the hands of another race. Could they conduct as successfully a county government in addition to their local government and still under the state and national governments of another race? Enough Negroes of the Mound Bayou type, and guided as they were in the beginning, will be able to do so.

The words I have quoted will, perhaps, illustrate the sort of interest and sympathy which the Mound Bayou experiment arouses in the minds of thoughtful Southerners. Now it is characteristic of Charles Banks that, in all his talks with me, he has never once referred to the work he is doing as a solution of the problem of the Negro race. He has often referred to it, however, as one step in the solution of the problem of the Delta. He recognizes that, behind everything else, is the economic problem.

Aside from the personal and business interest which he has in the growth and progress of Mound Bayou, Mr. Banks sees in it a means of teaching better methods of farming, of improving the home life, of getting into the masses of the people greater sense of the value of law and order.

I have learned much from studying the success of Charles Banks. Before all else he has taught me the value of common-sense in dealing with conditions as they exist in the South. I have learned from him that, in spite of what the Southern white man may say about the Negro in moments of excitement, the sober sentiment of the South is in sympathy with every effort that promises solid and substantial progress to the Negro.

Maj. R. R. Moton, of Hampton Institute, is one of the few black men I know who can trace his ancestry in an unbroken line on both sides back to Africa. I have often heard him tell the story, as he had it from his grandmother, of the way in which his great-grandfather, who was a young African chief, had come down to the coast to sell some captives taken in war and how, after the bargain was completed, he was enticed on board the white man’s ship and himself carried away and sold, along with these unfortunate captives, into slavery in America. Major Moton is, like Charles Banks, not only a full-blooded black man, with a big body and broad Negro features, but he is, in his own way, a remarkably handsome man. I do not think any one could look in Major Moton’s face without liking him. In the first place, he looks straight at you, out of big friendly eyes, and as he speaks to you an expression of alert and intelligent sympathy constantly flashes and plays across his kindly features.

It has been my privilege to come into contact with many different types of people, but I know few men who are so lovable and, at the same time, so sensible in their nature as Major Moton. He is chock-full of common-sense. Further than that, he is a man who, without obtruding himself and without your understanding how he does it, makes you believe in him from the very first time you see him and from your first contact with him, and, at the same time, makes you love him. He is the kind of man in whose company I always feel like being, never tire of, always want to be around him, or always want to be near him.

One of the continual sources of surprise to people who come for the first time into the Southern States is to hear of the affection with which white men and women speak of the older generation of coloured people with whom they grew up, particularly the old coloured nurses. The lifelong friendships that exist between these old “aunties” and “uncles” and the white children with whom they were raised is something that is hard for strangers to understand.

It is just these qualities of human sympathy and affection that endeared so many of the older generation of Negroes to their masters and mistresses and which seems to have found expression, in a higher form, in Major Moton. Although he has little schooling outside of what he was able to get at Hampton Institute, Major Moton is one of the best-read men and one of the most interesting men to talk with I have ever met. Education has not “spoiled” him, as it seems to have done in the case of some other educated Negroes. It has not embittered or narrowed him in his affections. He has not learned to hate or distrust any class of people, and he is just as ready to assist and show a kindness to a white man as to a black man, to a Southerner as to a Northerner.

My acquaintance with Major Moton began, as I remember, after he had graduated at Hampton Institute and while he was employed there as a teacher. He had at that time the position that I once occupied in charge of the Indian students. Later he was given the very responsible position he now occupies, at the head of the institute battalion, as commandant of cadets, in which he has charge of the discipline of all the students. In this position he has an opportunity to exert a very direct and personal influence upon the members of the student body and, what is especially important, to prepare them to meet the peculiar difficulties that await them when they go out in the world to begin life for themselves.

It has always seemed to me very fortunate that Hampton Institute should have had in the position which Major Moton occupies a man of such kindly good humour, thorough self-control, and sympathetic disposition.

Major Moton knows by intuition Northern white people and Southern white people. I have often heard the remark made that the Southern white man knows more about the Negro in the South than anybody else. I will not stop here to debate that question, but I will add that coloured men like Major Moton know more about the Southern white man than anybody else on earth.

At the Hampton Institute, for example, they have white teachers and coloured teachers; they have Southern white people and Northern white people; besides, they have coloured students and Indian students. Major Moton knows how to keep his hands on all of these different elements, to see to it that friction is kept down and that each works in harmony with the other. It is a difficult job, but Major Moton knows how to negotiate it.

This thorough understanding of both races which Major Moton possesses has enabled him to give his students just the sort of practical and helpful advice and counsel that no white man who has not himself faced the peculiar conditions of the Negro could be able to give.

I think it would do any one good to attend one of Major Moton’s Sunday-school classes when he is explaining to his students, in the very practical way which he knows how to use, the mistake of students allowing themselves to be embittered by injustice or degraded by calumny and abuse with which every coloured man must expect to meet at one time or another. Very likely he will follow up what he has to say on this subject by some very apt illustration from his own experience or from that of some of his acquaintances which will show how much easier and simpler it is to meet prejudice with sympathy and understanding than with hatred; to remember that the man who abuses you because of your race probably hasn’t the slightest knowledge of you personally, and, nine times out of ten, if you simply refuse to feel injured by what he says, will feel ashamed of himself later.

I think one of the greatest difficulties which a Negro has to meet is in travelling about the country on the railway trains. For example, it is frequently difficult for a coloured man to get anything to eat while he is travelling in the South, because, on the train and at the lunch counters along the route, there is often no provision for coloured people. If a coloured man goes to the lunch counter where the white people are served he is very likely, no matter who he may be, to find himself roughly ordered to go around to the kitchen, and even there no provision has been made for him.

RUFUS HERRON OF CAMP HILL, ALA.

“If there is a white man, North or South, that has more love for his community or his country than Rufus Herron, it has not been my good fortune to meet him.”

MAJOR ROBERT RUSSA MOTON

“It has been through contact with men like Major Moton that I have received a kind of education no books could impart.”

Time and again I have seen Major Moton meet this situation, and others like it, by going up directly to the man in charge and telling him what he wanted. More than likely the first thing he received was a volley of abuse. That never discouraged Major Moton. He would not allow himself to be disturbed nor dismissed, but simply insisted, politely and good-naturedly, that he knew the custom, but that he was hungry and wanted something to eat. Somehow, without any loss of dignity, he not only invariably got what he wanted, but after making the man he was dealing with ashamed of himself, he usually made him his friend and left him with a higher opinion of the Negro race as a whole.

I have seen Major Moton in a good many trying situations in which an ordinary man would have lost his head, but I have never seen him when he seemed to feel the least degraded or humiliated. I have learned from Major Moton that one need not belong to a superior race to be a gentleman.

It has been through contact with men like Major Moton—clean, wholesome, high-souled gentlemen under black skins—that I have received a kind of education no books could impart. Whatever disadvantages one may suffer from being a part of what is called an “inferior race,” a member of such a race has the advantage of not feeling compelled to go through the world, as some members of other races do, proclaiming their superiority from the house tops. There are some people in this world who would feel lonesome, and they are not all of them white people either, if they did not have some one to whom they could claim superiority

One of the most distinguished black men of my race is George W. Clinton, of Charlotte, N.C., bishop of the A. M. E. Zion Church. Bishop Clinton was born a slave fifty years ago in South Carolina. He was one of the few young coloured men who, during the Reconstruction days, had an opportunity to attend the University of South Carolina. He prides himself on the fact that he was a member of that famous class of 1874 which furnished one Negro congressman, two United States ministers to Liberia—the most recent of whom is Dr. W. D. Crum—five doctors, seven preachers, and several business men who have made good in after life. Among others was W. McKinlay, the present collector of customs for the port of George town, D.C.

Bishop Clinton has done a great service to the denomination to which he belongs and his years of service have brought him many honours and distinctions. He founded the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Quarterly Review and edited, for a time, another publication of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion denomination. He has represented his church in ecumenical conferences at home and abroad, is a trustee of Livingstone College, chairman of the publishing board, has served as a member of the international convention of arbitration and is vice-president of the international Sunday-school union.

PROFESSOR GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER

“One of the most thoroughly scientific men of the Negro race”

BISHOP GEORGE W. CLINTON

“He is the kind of man who wins everywhere confidence and respect.”

Bishop Clinton is a man of a very different type from the other men of pure African blood I have mentioned. Although he says he is fifty years of age, he is in appearance and manner the youngest man in the group. An erect, commanding figure, with a high, broad forehead, rather refined features and fresh, frank, almost boyish manner, he is the kind of man who everywhere wins confidence and respect.

Although Bishop Clinton is by profession a minister, and has been all his life in the service of the Church, he is of all the men I have named the most aggressive in his manner and the most soldierly in his bearing.

Knowing that his profession compelled him to travel about a great deal in all parts of the country, I asked him how a man of his temperament managed to get about without getting into trouble.

“I have had some trouble but not much,” he said, “and I have learned that the easiest way to get along everywhere is to be a gentleman. It is simple, convenient, and practicable.

“The only time I ever came near having any serious trouble,” continued Bishop Clinton, “was years ago when I was in politics.” And then he went on to relate the following incident: It seems that at this time the Negroes at the bishop’s home in Lancaster, S.C., were still active in politics. There was an attempt at one time to get some of the better class of Negroes to unite with some of the Democrats in order to elect a prohibition ticket. The fusion ticket, with two Negroes and four white men as candidates, was put in the field and elected. It turned out, however, that a good many white people cut the Negroes on the ticket and, at the same time, a good many Negroes cut the whites, so that there was some bad blood on both sides. A man who was the editor of the local paper at that time had accused young Clinton of having advised the Negroes to cut the fusion ticket.

“As I knew him well,” said the bishop, “I went up to his office to explain. Some rather foolish remark I made irritated the editor and he jumped up and came toward me with a knife in his hands.”

The bishop added that he didn’t think the man really meant anything “because my mother used to cook in his family” and they had known each other since they were boys, so he simply took a hold of his wrists and held them. The bishop is a big, stalwart, athletic man with hands that grip like a vise. He talked very quietly and they settled the matter between them.

Bishop Clinton has told me that he has made many lifelong friends among the white people of South Carolina, but this was the only time that he ever had anything like serious trouble with a white man.

I first made the acquaintance of Bishop Clinton when he came to Tuskegee in 1893 as representative of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, at the dedication of the Phelps Hall Bible training school. The next year he came to Tuskegee as one of the lecturers in that school and he has spent some time at Tuskegee every year since then, assisting in the work of that institution.

Bishop Clinton has been of great assistance to us, not only in our work at Tuskegee, but in the larger work we have been trying to do in arousing interest throughout the country in Negro public schools. He organized and conducted through North Carolina in 1910 what I think was the most successful educational campaign I have yet been able to make in any of the Southern States.

Although he is an aggressive churchman, Bishop Clinton has found time to interest himself in everything that concerns the welfare of the Negro race. He is as interested in the business and economic as he is in the intellectual advancement of the race.

One of the most gifted men of the Negro race whom I ever happened to meet is George W. Carver, Professor Carver, as he is called at Tuskegee, where he has for many years been connected with the scientific and experimental work in agriculture carried on in connection with the Tuskegee Institute. I first met Mr. Carver about 1895 or 1896 when he was a student at the State Agricultural College at Ames, Ia. I had heard of him before that time through Hon. James Wilson, now secretary of agriculture, who was for some time one of Mr. Carver’s teachers. It was about this time that an attempt was made to put our work in agriculture on a scientific basis, and Mr. Carver was induced to come to Tuskegee to take charge of that work and of the state experiment station that had been established in connection with it. He has been doing valuable work in that department ever since and, as a result of his work in breeding cotton and of the bulletins he has prepared on experiments in building up wornout soils, he has become widely known to both coloured and white farmers throughout the South.

When some years ago the state secretary of agriculture called a meeting at Montgomery of the leading teachers of the state, Professor Carver was the only coloured man invited to that meeting. He was at that time invited to deliver an address to the convention and for an hour was questioned on the interesting work he was doing at the experiment station.

Professor Carver, like the other men I have mentioned, is of unmixed African blood, and is one of the most thoroughly scientific men of the Negro race with whom I am acquainted. Whenever any one who takes a scientific interest in cotton growing, or in the natural history of this part of the world, comes to visit Tuskegee, he invariably seeks out and consults Professor Carver. A few years ago the colonial secretary of the German empire, accompanied by one of the cotton experts of his department, travelling through the South in a private car, paid a visit of several days to Tuskegee largely to study, in connection with the other work of the school, the cotton-growing experiments that Professor Carver has been carrying on for some years.

In his book, “The Negro in the New World,” Sir Harry Johnston, who has himself been much interested in the study of plant life in different parts of the world, says: “Professor Carver, who teaches scientific agriculture, botany, agricultural chemistry, etc., at Tuskegee, is, as regards complexion and features, an absolute Negro; but in the cut of his clothes, the accent of his speech, the soundness of his science, he might be professor of botany, not at Tuskegee, but at Oxford or Cambridge. Any European botanist of distinction, after ten minutes’ conversation with this man, instinctively would treat him as a man on a level with himself.”

What makes all that Professor Carver has accomplished the more remarkable is the fact that he was born in slavery and has had relatively few opportunities for study, compared with those which a white man who makes himself a scholar in any particular branch of science invariably has.

Professor Carver knows but little of his parentage. He was born on the plantation of a Mr. Carver in Missouri some time during the war.

It was a time when it was becoming very uncomfortable to hold slaves in Missouri and so he and his mother were sent south into Arkansas. After the war Mr. Carver, the master, sent south to inquire what had become of his former slaves. He learned that they had all disappeared with the exception of a child, two or three years old, by the name of George, who was near dead with the whooping-cough and of so little value that the people in Arkansas said they would be very glad to get rid of him.

George was brought home, but he proved to be such a weak and sickly little creature that no attempt was made to put him to work and he was allowed to grow up among chickens and other animals around the servants’ quarters, getting his living as best he could.

The little black boy lived, however, and he used his freedom to wander about in the woods, where he soon got on very good terms with all the insects and animals in the forest and gained an intimate and, I might almost say personal, acquaintance with all the plants and the flowers.

As he grew older he began to show unusual aptitude in two directions: He attracted attention, in the first place, by his peculiar knack and skill in all sorts of household work. He learned to cook, to knit and crochet, and he had a peculiar and delicate sense for colour. He learned to draw and, at the present time, he devotes a large part of his leisure to making the most beautiful and accurate drawings of different flowers and forms of plant life in which he is interested.

In the second place, he showed a remarkable natural aptitude and intelligence in dealing with plants. He would spend hours, for example, gathering all the most rare and curious flowers that were to be found in the woods and fields. One day some one discovered that he had established out in the brush a little botanical garden, where he had gathered all sorts of curious plants and where he soon became so expert in making all sorts of things grow, and showed such skill in caring for and protecting plants from all sorts of insects and diseases that he got the name of “the plant doctor.”

Another direction in which he showed unusual natural talent was in music. While he was still a child he became famous among the coloured people as a singer. After he was old enough to take care of himself he spent some years wandering about. When he got the opportunity he worked in greenhouses. At one time he ran a laundry; at another time he worked as a cook in a hotel. His natural taste and talent for music and painting, and, in fact, almost every form of art, finally attracted the attention of friends, through whom he secured a position as church organist.

During all this time young Carver was learning wherever he was able. He learned from books when he could get them; learned from experience always; and made friends wherever he went. At last he found an opportunity to take charge of the greenhouses of the horticultural department of the Iowa Agricultural College at Ames. He remained there until he was graduated, when he was made assistant botanist. He took advantage of his opportunities there to continue his studies and finally took a diploma as a post-graduate student, the first diploma of that sort that had been given at Ames.

While he was at the agricultural college in Iowa he took part with the rest of the students in all the activities of college life. He was lieutenant, for example, in the college battalion which escorted Governor Boies to the World’s Fair at Chicago. He began to read papers and deliver lectures at the horticultural conventions in all parts of the state. But, in spite of his success in the North, among the people of another race, Mr. Carver was anxious to come South and do something for his own race. So it was that he gladly accepted an invitation to come to Tuskegee and take charge of the scientific and experimental work connected with our department of agriculture.

Although Professor Carver impresses every one who meets him with the extent of his knowledge in the matter of plant life, he is quite the most modest man I have ever met. In fact, he is almost timid. He dresses in the plainest and simplest manner possible; the only thing that he allows in the way of decoration is a flower in his button-hole. It is a rare thing to see Professor Carver any time during the year without some sort of flower on the lapel of his coat and he is particularly proud when he has found somewhere in the woods some especially rare specimen of a flower to show to his friends.

I asked Professor Carver at one time how it was, since he was so timid, that he managed to have made the acquaintance of so many of the best white as well as coloured people in our part of the country. He said that as soon as people found out that he knew something about plants that was valuable he discovered they were very willing and eager to talk with him.

“But you must have some way of advertising,” I said jestingly; “how do all these people find out that you know about plants?”

“Well, it is this way,” he said. “Shortly after I came here I was going along the woods one day with my botany can under my arm. I was looking for plant diseases and for insect enemies. A lady saw what she probably thought was a harmless old coloured man, with a strange looking box under his arm, and she stopped me and asked if I was a peddler. I told her what I was doing. She seemed delighted and asked me to come and see her roses, which were badly diseased. I showed her just what to do for them—in fact, sat down and wrote it out for her.

“In this,” he continued, “and several other ways it became noised abroad that there was a man at the school who knew about plants. People began calling upon me for information and advice.”

I myself recall that several years ago a dispute arose down town about the name of a plant. No one knew what it was. Finally one gentleman spoke up and said that they had a man out at the normal school by the name of Carver who could name any plant, tree, bird, stone, etc., in the world, and if he did not know there was no use to look farther. A man was put on a horse and the plant brought to Professor Carver at the Institute. He named it and sent him back. Since then Professor Carver’s laboratory has never been free from specimens of some kind.

I have always said that the best means which the Negro has for destroying race prejudice is to make himself a useful and, if possible, an indispensable member of the community in which he lives. Every man and every community is bound to respect the man or woman who has some form of superior knowledge or ability, no matter in what direction it is. I do not know of a better illustration of this than may be found in the case of Professor Carver. Without any disposition to push himself forward into any position in which he is not wanted, he has been able, because of his special knowledge and ability, to make friends with all classes of people, white as well as black, throughout the South. He is constantly receiving inquiries in regard to his work from all parts of the world, and his experiments in breeding new varieties of cotton have aroused the greatest interest among those cotton planters who are interested in the scientific investigation of cotton growing.

There are few coloured men in the South today who are better or more widely known than Dr. Charles T. Walker, pastor of the Tabernacle Baptist Church of Augusta, Ga. President William H. Taft, referring to Doctor Walker, said that he was the most eloquent man he had ever listened to. For myself I do not know of any man, white or black, who is a more fascinating speaker either in private conversation or on the public platform.

Doctor Walker’s speeches, like his conversation, have the charm of a natural-born talker, a man who loves men, and has the art of expressing himself simply, easily, and fluently, in a way to interest and touch them.

On the streets of Augusta, his home, it is no uncommon thing to see Doctor Walker—after the familiar and easy manner of Southern people—stand for hours on a street corner or in front of a grocery store, surrounded by a crowd who have gathered for no other purpose than to hear what he will say. It is said that he knows more than half of the fifteen thousand coloured people of Augusta by name, and when he meets any of them in the street he is disposed to stop, in his friendly and familiar way, in order to inquire about the other members of the family. He wants to know how each is getting on and what has happened to any one of them since he saw them last.

If one of these acquaintances succeeds in detaining him, he will, very likely, find himself surrounded by other friends and acquaintances and, when once he is fairly launched on one of the quaintly humorous accounts of his adventures in some of the various parts of the world he has visited, or is discussing, in his vivid and epigrammatic way, some public question, business in that part of the town stops for a time.

Doctor Walker is a great story teller. He has a great fund of anecdotes and a wonderful art in using them to emphasize a point in argument or to enforce a remark. I recall that the last time he was at Tuskegee, attending the Negro conference, he told us what he was trying to do at the school established by the Walker Baptist Association at Augusta for the farmers in his neighbourhood. From that he launched off into some remarks upon the coloured farmer, his opportunities, and his progress. He said Senator Tillman had once complained that the coloured farmer wasn’t as ignorant as he pretended to be, and then he told this story: He said that an old coloured farmer in his part of the country had rented some land of a white man on what is popularly known as “fourths.” By the term of the contract the white man was to get one fourth of the crop for the use of the land.

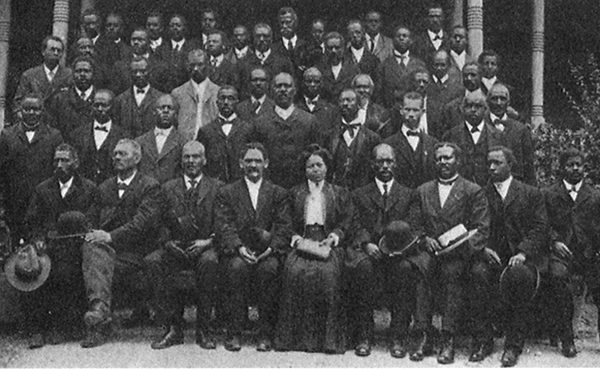

A MEETING OF THE NEGRO MINISTERS OF MACON COUNTY, ALABAMA

When it came time to divide the crop, however, it turned out that there were just three wagon loads of cotton and this the old farmer hauled to his own barn.

Of course the landlord protested. He said: “Look here, Uncle Joe, didn’t you promise me a fourth of that cotton for my share?”

“Yes, cap’n,” was the reply, “Dat’s so. I’se mighty sorry, but dere wasn’t no fort’.”

“How is that?” inquired the landlord.

“There wasn’t no fort’ ’cause dere was just three wagon loads, and dere wasn’t no fort’ dere.”

Doctor Walker is not only a fascinating conversationalist, a warmhearted friend, but he is, also, a wonderfully successful preacher. During the time when he was in New York, as pastor of the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, his sermons and his wonderful success as an evangelist were frequently reported in the New York papers.

Doctor Walker is not only an extraordinary pulpit orator, but he is a man of remarkably good sense. I recall some instances in particular in which he showed this quality in a very conspicuous way. The first was at a meeting of the National Convention of Negro Baptists at St. Louis in 1886. At this meeting some one delivered an address on the subject, “Southern Ostracism,” in which he abused the Southern white Baptists, referring to them as mere figureheads, who believe “there were separate heavens for white and coloured people.”

Later in the session Doctor Walker found an opportunity to reply to these remarks, pointing out that a few months before the Southern Baptist Convention had passed a resolution to expend $10,000 in mission work among the coloured Baptists of the South. He formulated his protest against the remarks made by the speaker of the previous day in a resolution which was passed by the convention.

His speech and the resolution were published in many of the Southern newspapers and denominational organs and did much to change the currents of popular feeling at that time and bring about a better understanding between the races.

Dr. Charles T. Walker was born at the little town of Hepzibah, Richmond County, Ga., about sixteen miles south of his present home, Augusta. His father, who was his master’s coachman, was also deacon in the little church organized by the slaves in 1848, of which his uncle was pastor. Doctor Walker comes of a race of preachers. The Walker Baptist Association is named after one of his uncles, Rev. Joseph T. Walker, whose freedom was purchased by the members of his congregation who were themselves slaves. In 1880, upon a resolution of Doctor Walker, this same Walker Association passed a resolution to establish a normal school for coloured children, known as the Walker Baptist Institute. This school has from the first been supported by the constant and unremitting efforts of Doctor Walker.

Meanwhile he has been interested in other good works. He assisted in establishing the Augusta Sentinel, and in 1891, while he was travelling in the Holy Land, his accounts of his travels did much to brighten its pages and increase its circulation.

In 1893 he was one of a number of other coloured people to establish a Negro state fair at Augusta, which has continued successfully ever since. Another of his enterprises started and carried on in connection with his church is the Tabernacle Old Folks’ Home. He has taken a prominent part in all the religious and educational work of the state and has even dipped, to some extent, into politics, having been at one time a member of the Republican state executive committee.

Aside from these manifold activities, and beyond all he has done in other directions, Doctor Walker has been a man who has constantly sought to take life as he found it and make the most of the opportunities that he saw about him for himself and his people. He has not been an agitator and has done more than any other man I know to bring about peace and good-will between the two sections of the country and the races. It is largely due to his influence that in Augusta, Ga., the black man and the white man live more happily and comfortably than they do in almost any other city in the United States.

The motto of Doctor Walker’s life I can state in his own words. “I am determined,” he has said, “never to be guilty of ingratitude; never to desert a friend; and never to strike back at an enemy.”

It is because of such men as Doctor Walker and many others like him that I have learned not only to respect but to take pride in the race to which I belong.

In seeking to answer the question as to the relative value of the man of pure African extraction and the man of mixed blood I have referred to five men who have gained some distinction in very different walks of life. There are hundreds of others I could name, who, though not so conspicuous nor so well known, are performing in their humble way valuable service for their race and country. I might also mention here the fact that at Tuskegee, during an experience of thirty years, we have found that, although perhaps a majority of our students are not of pure black blood, still the highest honours in our graduating class, namely, that of valedictorian, which is given to students who have attained the highest scholarship during the whole course of their studies, has been about equally divided between students of mixed and pure blood.

For my own part, however, it seems to me a rather unprofitable discussion that seeks to determine in advance the possibilities of any individual or any race or class of individuals. In the first place, races, like individuals, have different qualities and different capacities for service and, that being the case, it is the part of wisdom to give every individual the opportunities for growth and development which will fit him for the greatest usefulness.

When any individual and any race is allowed to find that place, freely and without compulsion, they will not only be happy and contented in themselves, but will fall naturally into the happiest possible relations with all other members of the community.

In the second place, it should be remembered that human life and human society are so complicated that no one can determine what latent possibilities any individual or any race may possess. It is only through education, and through struggle and experiment in all the different activities and relations of life, that it is possible for a race or an individual to find the place in the common life in which they can be of the greatest value to themselves and the rest of the world.

To assume anything else is to deny the value of the free institutions under which we live and of all the centuries of struggle and effort it has cost to bring them into existence.