Chapter Two

Fighting the Nazis

Bill Ash was nine years old in 1927, when the great pilot Charles Lindbergh came to Bill’s hometown of Dallas, Texas.

“Can you see him?” Bill asked his mother. “Is he coming?”

“Not yet, dear. But he will.”

“Lucky Lindy,” as Lindbergh was called, had just become the first person to fly alone across the Atlantic Ocean. Now, all over the United States, cities were throwing parades to honor this new American hero.

A chilly rain fell on that September afternoon as Bill and his mother joined thousands of others lining the street for the parade. Bill heard a roar sweeping through the crowd. The noise rolled closer to him as Lindbergh approached in an open car. He waved to the thousands of people along the street. Bill joined the crowd in waving back.

“Mr. Lindbergh!” Bill called. “Lucky Lindy! Hello!”

Bill watched as the car slowly inched past. And he thought, It must be great to be able to fly.

But after the parade, and during the next few years, young Bill Ash didn’t have too much time to think about flying. His family moved from one neighborhood to another in Dallas. His father sold hats for a living and sometimes struggled to pay the rent, so the family moved to find less expensive housing. Bill worked part-time in high school to help pay the bills, and he kept on working through college. During that time, the world was going through the Great Depression. When Bill left college, the world was facing another crisis: war in Europe.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

Bill Ash was just one of the millions of Americans affected by the Great Depression. This economic crisis began in October 1929. During the 1920s, many people had bought stock in US companies. The stock made them part owners of the companies. When the companies didn’t perform as expected, the value of many stocks began to fall. A great many people tried to sell their stocks all at once, causing a stock market crash. Banks did not have enough money in reserve to pay everyone who wanted to sell their stocks. People lost money, and some who had borrowed money to buy stocks could not pay back what they owed. Many companies also suffered, as people had less to spend on items for their homes or to buy cars. Companies fired workers, who often couldn’t find new jobs. By 1933, about 25 percent of Americans were out of work. They struggled to feed their families or find housing they could afford. The Great Depression spread around the world and lasted through the 1930s.

Bill read in the papers about Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party, who had started the war in Europe by invading Poland in September of 1939. France and Great Britain soon came to Poland’s aid. But the Nazis of Germany had built a powerful military force and easily took control of Poland.

Bill saw the danger Germany posed to other democratic nations. He read about how Hitler was locking up Jewish people, who had committed no crimes, in concentration camps. Now Hitler wanted to conquer large parts of Europe. The Allied countries agreed that the war in Europe was fueled by Hitler’s desire for power and his hatred of Jews and others he considered less human than Germans.

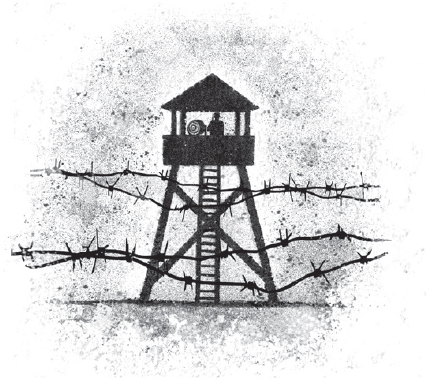

CONCENTRATION CAMPS

Long before the Nazis built Stalag Luft III and other POW camps, they had set up another type of camp all across Germany. These were called concentration camps, where Adolf Hitler sent anyone who he thought threatened his rule, such as political opponents, and anyone he deemed “inferior.”

The worst of these camps were the Nazi’s six death camps, where they murdered millions of innocent people for no reason other than that Hitler and the Nazis considered them “racially undesirable.” In an attack known as genocide, the Nazis killed six million Jews, at least 1.9 million Poles, and hundreds of thousands of Romany people (who were also known as Gypsies), gay people, people with disabilities, religious officials, and members of political parties that opposed the Nazis.

Before being killed, prisoners in concentration camps first had to work for the Nazis. Some cut trees or dug for minerals in mines, while others constructed roads and buildings, often working fourteen hours a day, seven days a week. Guards watched closely as the prisoners worked, and many soldiers took pleasure in beating the prisoners. Unlike POW camps, concentration camps were not governed by international rules protecting prisoners.

The Nazis’ deliberate mass killing of more than six million Jews is known today as the Holocaust. Most of the people who died in the Holocaust were killed by poisonous gas, but some also died from disease and starvation.

But in the summer of 1940, the United States had not yet gotten directly involved in the war. Some Americans even openly supported Hitler. As Bill Ash traveled the country looking for work, he sometimes got into fights over the issue. After one brawl, a bystander called out, “If you hate Hitler so much, why don’t you go fight him.”

“I just might do that,” Bill replied.

Then in 1940, Ash wound up in Detroit. While eating a meal at a diner, he looked at the other young men eating nearby.

“Boys, wish me luck,” Ash said. “I’m going to Canada to join the air force and shoot down some Nazis.”

The others in the diner laughed. To most Americans, the war was something that was happening far away and had nothing to do with them. But the young men quieted as they saw Ash leave the diner and start walking to the nearby border with Canada. They realized that he was serious. However, a short time later, Ash returned to the diner.

“Hey, hotshot,” one man called out. “How many Nazis did you kill?”

Ash looked down. “They didn’t take me,” he said. “They said I was too skinny.”

Ash borrowed some money, then began to eat as much food as he could. He stuffed himself day after day. Two weeks later, he returned to Canada and tried to volunteer again.

The recruiting sergeant looked him over, then told him to step onto a scale. The sergeant checked his weight.

“Okay,” he told Ash. “You’re in.”

Ash smiled as the others in the room cheered. “Welcome aboard, Yank,” someone called out. Fighting for a foreign air force meant Ash had to give up his US passport and citizenship. But he didn’t care. All he wanted was to go to Europe, fly planes, and help defeat the Nazis.

Other “Yanks” joined Ash in volunteering for Canada. Although an independent nation, Canada had close ties with Great Britain, and British pilots trained the Canadians and the Americans who volunteered. Like Ash, those Americans wanted to fight Hitler right away, rather than wait to see if the United States entered the war.

As he trained, Ash discovered that he had a natural talent for flying. He also followed the events in Europe. British pilots in the Royal Air Force were heroically battling German planes over the skies of England. When Ash and the others finished their training, they too would fly for the RAF.

Some of the men learning how to fly wondered if the war would even last that long.

“The Germans are dropping so many bombs every day,” one young pilot said. “And they just invaded France.”

“It doesn’t look good,” another pilot agreed. “I don’t know if we’ll be able to stop them.”

“Now, don’t get so down,” Ash said. “The RAF will hold off those Germans, and before you know it, we’ll be over there shooting down Nazi planes, too.”

As it turned out, Ash was right. The training in Canada soon ended, and he and the others headed to England. In the spring of 1941, Ash climbed into the cockpit of a Spitfire aircraft for the first time. He was about to fly one of the world’s best fighter planes.

Ash looked over all the controls. With the touch of a button, he could fire the plane’s machine guns at an attacking enemy. Once he was airborne, any fear Ash felt vanished as he guided the powerful aircraft through the skies during his final training missions. I can do this, he thought. I can fly a Spitfire as good as anybody!

By the fall of 1941, his training was over. Ash finally got a chance to face the Nazis in the air. On his missions, he and other Spitfire pilots often protected ships and slower bomber planes as they headed for their targets. He loved the speed and agility of the Spitfire. It’s like driving a sports car, he thought—except for the German guns firing at me from down on the ground.

When he landed, Ash would check the outside of the plane to see how many times he had been hit but still managed to keep flying. Others, though, were not so lucky. Ash knew plenty of pilots who never made it back alive. For almost six months, Ash flew dangerous missions, always managing to return to his home base in the town of Hornchurch, just outside London.

On March 24, 1942, Ash headed to the airfield for another mission. The mist began to clear, and fighter planes and bombers took off for a target in Belgium. On the way back after a successful run, his radio blared to life.

“Enemy planes closing in!” another pilot warned. Ash made a sharp turn to try to spot them. Within seconds, he was firing his machine guns, watching the bullets rip into a German plane. It fell out of the sky in a cloud of gray smoke.

But more German planes were soon circling around him. Ash aimed at another fighter plane and fired again, but this time his guns jammed. Then he felt the plane begin to slow. Ash’s mind raced. The engine’s been hit—now what do I do? He could see more German fighters approaching. Either I bail out, or I crash.

He knew that floating down to earth with a parachute would make him an easy target for the German guns. As his Spitfire neared the ground, Ash looked for a good place to crash-land. He was flying over France, and he could only hope that once he landed a friendly French citizen would find him before the Germans did.

SPITFIRES AND OTHER AIRCRAFT OF WORLD WAR II

The first practical airplane flew in 1903, and by 1914, when World War I broke out, countries around the world realized planes would be useful in war. They could scout out enemy positions, and pilots could also drop bombs and fire machine guns from the air at troops on the ground. The first military planes were made mostly of wood and strong fabric, and the pilots sat in an open cockpit. Most of the planes had two sets of wings, though some had as many as three, stacked one on top of the other.

As World War I went on, air forces developed a strategy that continued in World War II. Larger planes were equipped with bombs, while faster fighter planes protected them from enemy planes.

The plane Bill Ash flew in World War II, the Spitfire, was one of the best fighter planes made.

By the time World War II started, airplanes were being made of aluminum and most had just one set of wings. Pilots could also talk to each other using radios. Throughout the war, Great Britain kept improving the Spitfire, and by 1943 some models had a top speed of 440 miles per hour and could reach an altitude of 40,000 feet.

Pilots like Ash appreciated how easy it was to fly the Spitfire, and the plane and its pilots were famous for winning many “dogfights” in the air against German airplanes. The Spitfires often confronted German fighter planes called Messerschmitt Bf 109s.

The Spitfire was a little faster, but the German plane flew better at higher altitudes.

In 1944, Germany produced the most advanced plane of the war—the Messerschmitt Me 262. It was the world’s first plane powered by a jet engine and had a top speed of about 540 miles per hour. By the time these planes first saw action, however, Germany was starting to lose the war. US and British bombers were able to destroy some of the jet fighters while they were still on the ground. By the war’s end, some British bombers could carry up to eleven tons of bombs on one flight.