Chapter Five

Another Try

For thirty-six hours, Bill Ash and the other prisoners being transferred sat on stiff wooden seats on the train they were riding toward their new camp in Schubin, Poland. When they arrived, they immediately saw something that they believed would help with an escape. The camp had been built as a school, not a prison, and some of the buildings were close to the barbed-wire fences that surrounded the place.

“This means we don’t have to dig long tunnels,” Ash noted.

“And if we do get out,” Barthropp said, “we’ll be in a country that hates the Germans as much as we do.”

Back in the United States, Ash had read plenty of newspaper reports about Germany’s brutal invasion of Poland in 1939. More than one hundred thousand Poles had died or been sent to prison since Germany’s invasion. Because of that, Ash figured he could count on the help of many Polish civilians, even though they risked being shot by the German forces in their country. Of course, Ash knew he had to get out of the prison camp first.

Once the new prisoners settled in, members of the new camp’s escape committee asked Ash and Barthropp to join them. Ash liked the idea that now he would have a say in how escapes would be carried out. But before the committee approved a major escape attempt, Ash decided to try one on his own.

The camp held both officers and men of lower rank. By international law, the officers did not have to work. But Ash decided to join a group of privates who were being sent out of the camp to unload supplies at the local train station. A long coat covered his lieutenant’s uniform, but one of the privates recognized him as an officer.

“What are you doing?” the private asked.

Ash replied with a smile, “Oh, I just thought I’d get some fresh air outside the camp.”

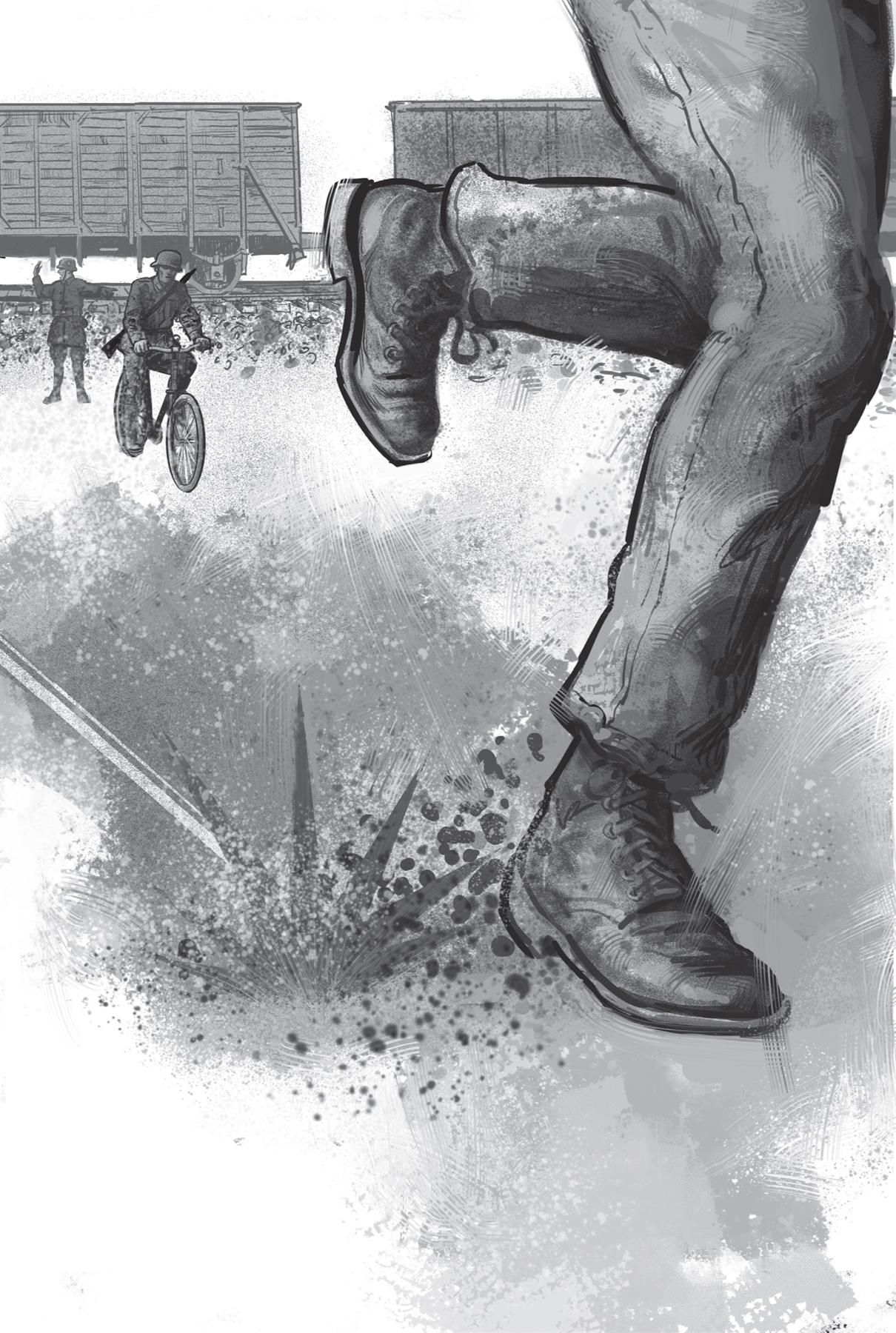

As the prisoners marched to the station, German soldiers kept their rifles ready. At the station, Ash kept an eye on the guards as he approached a train. When the guards weren’t looking, he slipped between the train cars and ducked behind the train on the opposite side of the tracks. He scanned the countryside. Surrounding the station was a large, open field, but beyond that was the edge of a forest. If I can just reach those trees, Ash thought, I might have a chance.

Ash took a deep breath, then sprinted away from the train. In seconds, he heard a rifle shot ring out and felt a bullet whiz over his head. He was still far away from the forest. As he ran, Ash looked back and saw two German soldiers on bicycles quickly gaining on him. They soon circled around him.

I guess I should give up, Ash thought. But the idea flashed out of his head, and instead he tried to plow through the two men. A rifle butt smashed into his face, and Ash crumpled to the ground. His head throbbing with pain, Ash knew he was due for another trip to the cooler.

Weeks later, as winter approached, Ash came up with another escape idea. He gathered with a group of men outside the latrine, the building that held the prisoners’ toilets.

“We should start a tunnel here,” he said. “Inside the latrine, the goons won’t see us digging, and we have a reason to be in there anytime. Plus, it’s only about 150 feet to the outside of the camp.” The other men liked the idea. Soon, about twenty-four prisoners were at work digging their tunnel.

Inside the latrine, the men removed some of the concrete bricks in one wall and began to dig. The latrine had a large pit to collect human waste. The awful smell from the pit filled their noses, but the men tried to ignore it. And Ash knew the pit was actually a good thing. Once a month, Polish civilians came to pump out the waste—and any dirt that was mixed into it.

“The pit is perfect for us,” Ash said. “We can hide the dirt we dig in there.” That solved one of the biggest problems in digging an escape tunnel—where to hide the dirt so the guards wouldn’t see it. Another challenge was keeping the camp’s ferrets from hearing the digging. The Germans put microphones underground to listen for the sounds diggers would make. Ash and the others decided to dig their tunnel almost twenty feet below the surface, to make it harder for the microphones to pick up the sound.

Ash and a Canadian prisoner named Eddy Asselin were in charge of the digging. Paddy Barthropp and several others helped out, and eventually all twenty-four men took turns shoveling out the dirt. While that work went on, other men tried to get useful information and items. They were called “traders,” and they talked to friendly guards or Polish civilians who worked in the camp. The men traded cigarettes and chocolate from their Red Cross packages for maps and other practical things, such as clothing. Prisoners who were called “tailors” used that clothing and some sent by the Red Cross to make clothes similar to what the locals had for the escapees to wear when they left the camp.

In the tunnel, the work was slow and steady. Since they were working in almost total darkness, Ash and the others carried small lamps made from tin cans filled with margarine, which would burn, and a shoelace as a wick.

To make it easier to breathe in the tight space, the men fashioned a long tube made of empty metal cans. The cans had come in their Red Cross packages. The POWs turned a canvas bag into a bellows—a device for pumping air. Someone outside the tunnel moved the bellows back and forth to pump fresh air through the cans down to the men digging below.

To keep the tunnel from collapsing, the men took wooden boards from their beds and used them to brace the dirt walls and ceiling. Ash soon had no boards left on his bed, and he slept on top of a net he made from string, which held up his mattress.

As the tunnel grew longer, some of the men began to worry a bit. “It’s so cramped in there,” Asselin said to Ash. “Even with the air pumps, sometimes I feel like I can’t breathe. And what if the tunnel collapses?”

“Then we die,” Ash said calmly. “Come on, we’ve gone sixty feet already. Keep digging.”

Ash tried to encourage the others, but he knew that this was no easy task. At times, the margarine lamps went out, and the men worked in total darkness. The cold clay and dirt that surrounded them seemed to fill their bodies, and bits of earth sometimes fell all around them. To make it worse, smells from the latrine sometimes filled the tunnel, making the men gag.

In the worst moments, Ash thought to himself, all this will be worth it when we finally get out. And when the thought of quitting flashed through his head, he remembered his plane crash. He pictured Marthe and Julien Boulanger and all the brave Resistance members who had risked their lives to help him. He thought of the people across Europe suffering because of the Nazis. Then he took his little tin scoop and went back to chipping away again at the dirt wall in front of him.

The digging and the planning for the escape took months. Finally, in March 1943, one year after he crash-landed and about six months after arriving at Schubin, the tunnel was ready. On March 5, a moonless night, thirty-three men prepared to go. They wore clothing made by the tailors. They carried forged papers that said they were civilians. These papers even had photographs. A friendly Polish worker had sneaked a camera to the prisoners for that purpose. After the five p.m. roll call, the men began to head to the latrine. They waited for several hours before starting to crawl through the tunnel. Ash felt as he had before taking off in his Spitfire—a little nervous, but totally excited.

Ash and Asselin were the first in line to go through the tunnel. They had the job of digging out the last bit of dirt on the surface outside the camp. As they waited for the signal to go, they discussed their plans. “We’ll head for Warsaw,” Ash said. Asselin nodded. In the Polish capital, they could contact the Resistance there. Some of the men were going to try to take trains, but Ash preferred to go on foot. “The Poles will help us, I know,” he said. “Look at how many have already risked their lives so we could get this far with the tunnel.”

As the men gathered in the latrine, Ash explained to some who had not been in the tunnel before what it would be like. “You have to push your bag in front of you as you crawl on your knees. Use your elbows and toes, too. Whatever you do, don’t grab at the wooden boards! If one comes down, the whole tunnel could collapse.”

By seven thirty p.m., twenty-six men were on their knees inside the tunnel. The rest waited in the latrine for their turn. Asselin and Ash dug out the last bit of earth at the end of the tunnel. Asselin broke through the ground first. Soon, Ash saw trees and bushes above him and felt the cold night air. He took a deep breath, smiled, and then turned to his partner.

“Eddy, that’s what freedom smells like.”