Chapter Seven

Another Camp, Another Escape

Pulling into the camp, Ash could see that the Germans had expanded Stalag Luft III over the past few months. Some of the new buildings housed captured US pilots. The Americans had been flying missions in Europe since the summer of 1942, seven months after the United States finally entered the war.

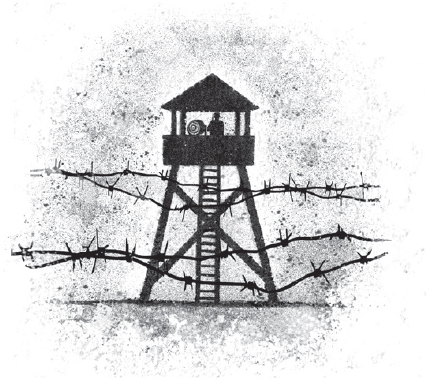

“It’s nice to see so many Americans again,” Ash said to Asselin. But he soon realized that he wouldn’t have much contact with his fellow countrymen. The RAF pilots and the Americans were kept in separate compounds. Barbed-wire fences cut off one from the other, and guards with machine guns watched the strip of dirt that stood between them. The POWs called it “no-man’s-land.”

Ash learned that some of his old friends at Stalag Luft III were still trying to dig tunnels, and that new men had joined them. But the effort had gotten much harder.

“The ferrets have gotten smarter,” one British officer told him. “They drive heavy vehicles around the camp, hoping to make tunnels collapse. And they measure the dirt under the barracks. When it starts going up, they know we’re putting there what we’ve dug out.”

“I wonder if it would be easier to get out of another camp,” Ash said.

“Maybe. But you’re in this one.”

Ash smiled. “For now.”

He was already working on a new escape plan. He had heard that a group of sergeants were going to be moved from Stalag Luft III to a camp in Lithuania. If I can get in with those guys, Ash thought, I can get to that other camp—one that might be easier to break out of. Officers like Ash lived in different compounds from the sergeants who were going to be moved, with a barbed-wire fence in between them. Keeping a careful eye out for the guards, Ash was able to speak with prisoners on the other side of the fence. Communicating this way, Ash found a New Zealand sergeant named Don Fair who was ready to change places with him. Fair did not want to try an escape himself, but he was willing to help out a fellow prisoner. Plus, if he pretended to be an officer, Fair would no longer risk being sent to Lithuania.

“All we have to do is swap identity papers,” Ash said. “You’ll become Bill Ash, and I’ll be Don Fair.”

Fair looked doubtful. “Except first we have to get out of our fenced-in areas without the guards killing us.”

Ash recruited some other officers to pretend to start a fight. Their shouts distracted the guards. Then Ash and Fair each carefully scrambled up the wire fence that surrounded their compounds. They met in the no-man’s-land in between. Ash stuck out his hand to shake Fair’s, and then the two men traded papers.

“Good luck, Sergeant Fair,” the real Fair said to Ash with a smile.

Ash then began to climb up the other wire fence. It was ten feet tall, but as he went up, Ash felt like it was one hundred feet. He waited for a rifle shot and the piercing pain of a bullet hitting him in the back. It never came. The guards were watching the fake fight and didn’t spot him. Ash dropped down safely into the other compound. Soon, he and the others headed to the train station for the trip to their new “home.”

It didn’t take long for the prisoners at the new camp, Stalag Luft VI, to learn who “Sergeant Don Fair” really was and to hear about his vast experience with trying to escape POW camps. Ash was soon on this camp’s escape committee. The committee went to work creating an organized system for planning and carrying out escapes. Part of the system included finding traders to get the important supplies they would need. Another part was focusing on one tunnel at a time.

Ash and some other prisoners began digging a tunnel under a laundry room. But unlike in Schubin, the men could not dig too deep. If they did, water from underground springs would rush into the tunnel. At the same time, the tunnel could not be too close to the surface. Once again, the ferrets had microphones to listen for the sound of digging.

The work was slow and steady, as the tunnel grew to 150 feet long. The leader of the prisoners in the compound, Jimmy Deans, congratulated Ash on their progress.

“But I think the commandant knows something is going on,” Deans said. “He asked if I knew anything about a tunnel.”

“What did you say?” Ash asked.

“I said I didn’t know of anything going on in the camp that shouldn’t be going on.” Deans then added with a smile, “Of course, in my opinion, digging a tunnel is exactly what should be going on in a POW camp.”

The commandant, however, remained suspicious. Soon, Gestapo men were crawling through the camp, looking for signs of an escape attempt. Ash saw them carry maps and clothing out of several barracks. But no sign that they found the tunnel, Ash thought to himself. Still, the escape committee knew the Germans were focused on finding their tunnel, if it existed. The diggers had brought the tunnel outside the camp, but they were short of the planned target, which was a group of trees that would help hide the escape. The men discussed what to do next.

“Keep digging,” someone said. “We’ve kept the tunnel a secret for this long.”

Ash shook his head. “I say stop digging and get as many men out now, while we can. The more we dig, the more we risk the Nazis finding it.”

Finally, the men who were to take part in the escape voted. They wanted to stop digging and get out as soon as they could.

On the night of the escape, fifty men prepared to go. In their beds, they left behind dummies made from papier-mâché, with their heads covered with real hair. The men had made the dummies in art classes the Germans offered, part of their efforts as spelled out in the Geneva Conventions to help the prisoners pass the time.

As in Schubin, Ash was at the front of the line in the tunnel. Though he had favored the early escape, he worried about what he would find on the surface. The tunnel comes out close to the fence, he thought. And those trees are a long way out.

He pushed through the long, dark tunnel. The men had set up a system to bring in fresh air while they were digging, but it was no longer working. The farther Ash went, the more he struggled to breathe. Finally, he reached the spot where the tunnel turned upward, toward the surface. He dug out the last bit of dirt and felt cool, fresh air wash over him. He took a deep breath. “Oh, that is good,” he said to himself. Behind him, he heard the others sigh with relief as the air began to reach them.

Ash poked his head above the ground. He heard footsteps nearby, inside the camp, and ducked back down. When the German guard passed, he climbed out of the hole. Bracing himself, he dashed toward the trees about thirty feet away. Thirty feet, he thought. Might as well be thirty miles when you know you might take a bullet any second.

Ash made it to the trees, then looked back to see other men popping out of the tunnel and sprinting toward him. But he didn’t watch for long. He turned and started running through the trees. He hadn’t gotten far when he heard gunfire behind him. The Nazis have spotted us, he thought. The rifle shots were quickly followed by the barks of the Germans’ dogs. Ash put his head down and ran as fast as he could.