Chapter Nine

The Last Escape

I feel like I’m coming home, Ash thought as he entered the camp. He saw many familiar faces in the compound. Paddy Barthropp, though, and some of his other old pals were now in a different compound within the camp.

Ash soon learned that many of the men at Stalag Luft III were already at work on three new tunnels. The prisoners nicknamed them Tom, Dick, and Harry. But before Ash could think about any more underground digging, he was thrown into the cooler.

“They should call you the Cooler King,” one prisoner said as the guards hauled Ash toward the tiny cell.

“The Cooler King. I kinda like that,” Ash said with a smile. But once inside the cooler, he saw, again, that there was nothing kingly about the tiny cell that would be his home for the next two weeks.

When he got out of the cooler, Ash took some time to rebuild his strength. But it didn’t take long for him to try once again to escape. Walking around the compound one day, he saw a truck parked near the gate. It sat with its motor running as a guard searched the back of the truck. When the guard was done, he turned and walked away.

This is my chance, Ash thought as he bolted toward the back of the truck. He jumped in without the guard seeing him. The truck began to head out of the camp, but then Ash felt it slow down and finally stop. Ash heard soldiers outside. Seconds later, one of them peered into the back of the truck and saw him. Within minutes, Ash was back in the cooler.

Ash was used to life in this cell. Mostly, he sat and thought about the war, people he knew, what he had gone through. He thought about his mother back in Texas. She had written to him several times since his capture. In one letter, she described how she was baking apple pies for German POWs held in America. He laughed as he remembered her next line: “I hope the German mothers are doing the same thing for you.” Ash hadn’t tasted an apple pie in years.

Yeah, the war sure has changed my life, he thought. But he had no regrets about wanting to fight Hitler and Nazis. Good people have to stand up to evil wherever they see it. Ash knew the war would be over soon, since the Allies were pounding Germany with bombs every day. But he still wanted to escape and fight the Nazis again.

One night in the cell, Ash heard sirens go off in the camp. “Escape!” he said to himself. “Paddy and the boys must be putting those new tunnels to good use.”

But when he finally got out of the cooler in April 1944, Ash learned more about what was soon called the Great Escape. Almost eighty men had fled the camp on the night of March 24. Fifty had been recaptured and shot by the Gestapo. That news stunned Ash and the other prisoners. The Germans were cracking down on escapees—perhaps because they sensed the war was coming to a close and they were going to lose.

THE GREAT ESCAPE

Bill Ash was in the cooler when the biggest escape attempt of the war took place. While several officers played key roles in planning the escape, Roger Bushell was the leader. A pilot who had been shot down in 1940, Bushell had tried to escape several times before he organized the construction of the three tunnels nicknamed Tom, Dick, and Harry. Eventually, Bushell and the others put all their efforts into Harry. When the tunnel was finished, it had electric lights, with the power coming from wiring in the barracks. Using stolen materials, the prisoners built a small railway in the tunnel out of wood.

A cart on wheels rode on the tracks, hauling out dirt. To get the dirt out of the tunnels, prisoners carried it in bags inside their pants, then dumped the dirt around the compound. The men who carried the dirt using the bags were called penguins, because the bags made them waddle like those birds as they walked. Working this way, the penguins spread out more than one hundred tons of sand.

On the night of the escape, two hundred prisoners were supposed to go out the tunnel. Only seventy-six made it outside Stalag Luft III before the Germans discovered the escape. Three—two Norwegians and a Dutchman—managed to avoid capture and win their freedom. Roger Bushell was one of the fifty POWs recaptured and shot by the Germans.

In 1963, the movie The Great Escape showed the efforts of the hundreds of men who built Harry and tried to escape from Stalag Luft III.

While the movie was based on actual events, not everything in it was true. The lead character was an American prisoner named Virgil Hilts, who did not exist in real life. He had the nickname of the “Cooler King.” Some people have suggested that Hilts was based on Bill Ash. Ash wrote years later that no one connected with making the movie ever told him he was the model for Hilts. In reality, the filmmakers probably based the character on several real-life POWs.

In any event, the Gestapo decided it would take control of Stalag Luft III and the other prison camps. They were bound to be stricter than the Luftwaffe officers had been. But that wouldn’t keep Ash from trying to escape again.

He joined several others to form yet another escape committee in their compound. “We should try to work with the Americans in the compound next door,” one officer said. The others on the committee agreed, and they picked Ash to climb the fences separating the compounds to go talk with the Americans. They seemed interested in trying another escape. But a new development in the war soon changed their plans.

Back in his own compound, Ash heard shouting coming from outside his barracks. “They’ve landed! The Allies have reached France!”

The news came over one of the simple radios the men had built using stolen and smuggled parts. Finally, the Allies had sent troops to France to push the Germans out of the lands they controlled. Bombing raids had destroyed many German factories, but Ash and so many others knew that a land attack was the only way to truly defeat the Germans and end the war. In the weeks that followed, Ash closely followed the news broadcast over the secret radio. He and the other prisoners tracked the Allies’ effort to drive the Germans out of France.

Ash saw that even fewer men were ready to risk an escape now. Two had dug a short tunnel, but now they decided not to use it. Ash, though, was ready to try escape again, and he found two more POWs eager to go with him. The other prisoners, however, did not like the idea.

“If you get caught,” one said, “the Gestapo might punish us.”

Those fears led the commanding officer in the compound to cancel the escape attempt. A disappointed Ash realized he would most likely spend the rest of the war as a prisoner.

By the beginning of 1945, the Allies had reached Belgium and were close to Germany’s western border. In Eastern Europe, the Russians were also pushing back the Nazis. The bitterly cold winter was easier to take as the prisoners heard Soviet artillery slowly getting closer.

Soon the Gestapo had the men marching out of Stalag Luft III to another camp miles away in Germany. Day after day, Ash and the others trudged through ice and snow. When the water ran out, the men melted snow and gulped down the cold liquid. Around Ash, prisoners and guards alike developed frostbite as the temperature fell below freezing.

As the men passed through small villages, the residents came out to stare. Ash traded some of the cigarettes and chocolate from his Red Cross packages for food. I should have grabbed more chocolate, Ash thought, as he saw how eager the Germans were for this treat.

The marching finally ended when the prisoners reached the small town of Spremberg. There, the soldiers crammed them into train cars normally used to carry cattle. The cars stank from the cattle’s waste, and the men were jammed into the car so tightly, they could not sit down. Ash still had no idea where the Germans were taking them, or even if they would let the prisoners live. For days, rumors had spread that they would all be shot.

By now, Ash was sick, his skin turning yellow from a liver disease called jaundice. The Germans took him and other sick prisoners off the train and brought them to a military hospital near the Marlag und Milag Nord camp outside Bremen.

After a few weeks, Ash recovered from his illness. By the spring of 1945, however, the war came to the camp. German troops had taken it over, filling it with tanks and artillery. They were convinced the Allies would not attack their own troops. I wouldn’t bet on that, Ash thought, and sure enough, British artillery shells soon began to explode within the camp. The Germans returned fire.

As the fighting went on through the day, Ash thought about all his escape attempts so far. Close to a dozen, I bet. Well, why not go for one more? Better to die that way than just sitting here waiting for a shell to hit me.

As bullets flew around him and shells exploded inside and outside the camp, Ash paused for a moment. Despite all he had seen and experienced during the war, he felt his knees shake with fear. The trembling got so bad he could barely stand. Then he heard cries for help coming from the hospital. Men too weak to get out of their beds were just lying inside, with no chance to take cover from the shells landing all around the camp. Ash felt his legs regain their strength. Somebody’s got to help those poor guys, he thought. And it might as well be me.

Several other prisoners had the same idea. They joined Ash as he headed into the hospital. Ash went to a bed and saw a prisoner who could barely move. “Come on, buddy,” Ash said. “Let’s get you out of here.” Ash picked up the man and gently lifted him onto his back. As Ash carried him out of the hospital, he heard the man mumble, “Thank you.”

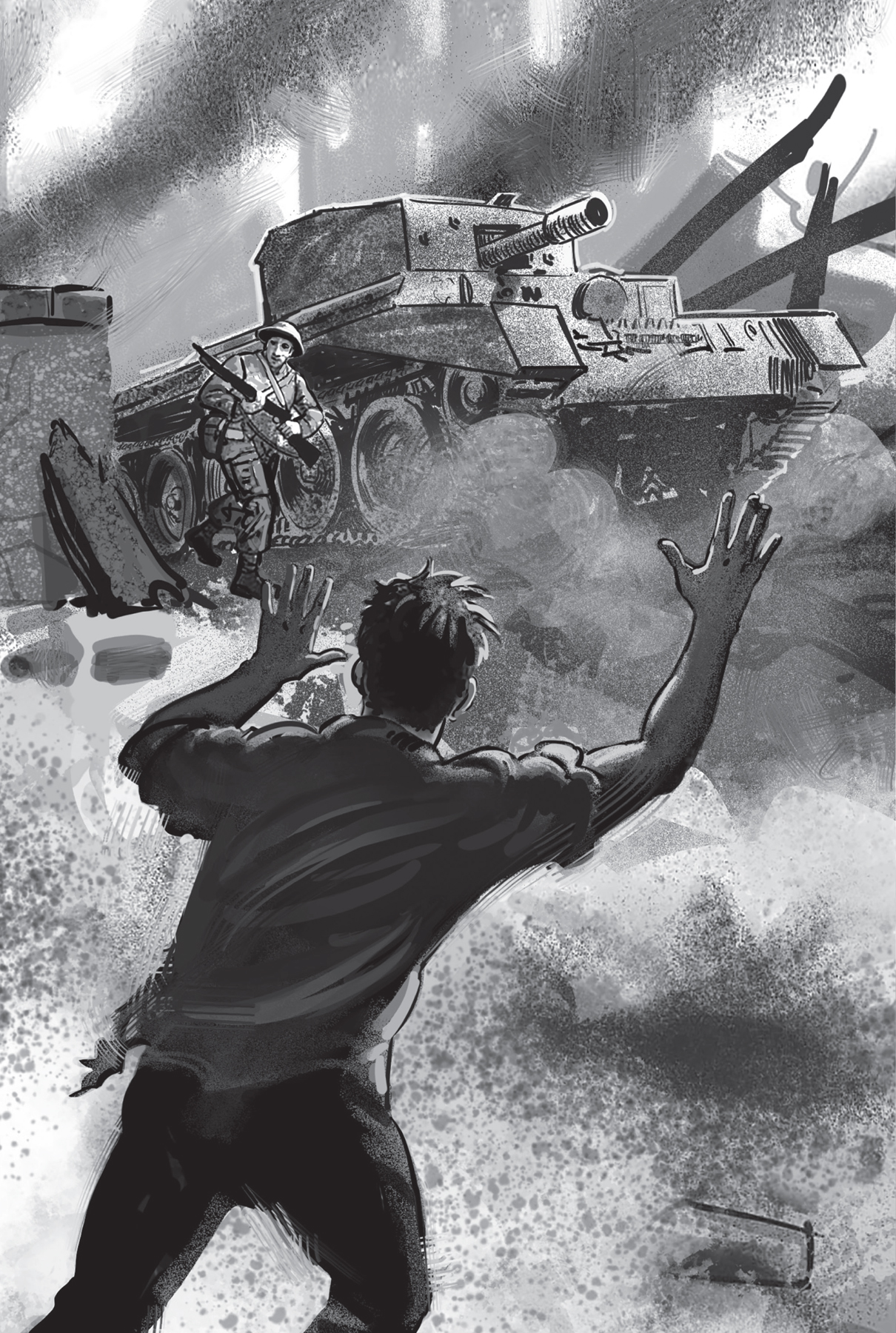

Ash realized he could help more prisoners if he could escape and reach the British lines. If I tell them where most of the prisoners are, they can try to avoid them when they fire. With a deep breath, Ash bolted toward the wire fence. One way or another, he knew this would be his last escape.

Bullets whizzed close by as he ran. He dodged the holes in the ground that the exploding shells made, each blast sending up a spray of dirt. Finally, he was through the fence and out of the camp. He ran until he saw a tank up ahead—a British tank. Ash hoped his worn-out clothes would let them know he was a POW and not a German soldier. A soldier near the tank pointed his gun toward Ash, who had his hands up.

The soldier put down his gun down and shouted, “Don’t shoot! He’s one of us!” Ash told the men where the Germans had positioned their tanks and guns in the camp. He also informed them where the prisoners were.

Soon, the Germans in the camp pulled out, leaving behind their prisoners. The British thanked Ash and gave him food and cigarettes.

“Boys,” Ash said, “all I need right now is a little rest.”