The strategic weakness of the Great Wall stood in marked contrast to its superb operational strength. At a battlefield level its formidable towers, rapidly traversable walkways and solid gates were virtually impregnable to a predominantly cavalry-based enemy. But the strength of the Great Wall as a defensive system depended upon much more than merely bricks and mortar, no matter how impressive their combination may have looked. Without the men to guard it the Great Wall was useless, but we must not therefore imagine that its walkways were constantly thronged by soldiers gazing northwards in the hope of spotting a Mongol raid. Less than a third of a guard’s time would have been spent on military duties. Most of his day would have been spent working in the fields nearby; because one crucial aim of the Great Wall system was that its garrisons should be self-sufficient in food. The border settlers carried out farming, and higher-ranking soldiers were allowed to have their families with them.

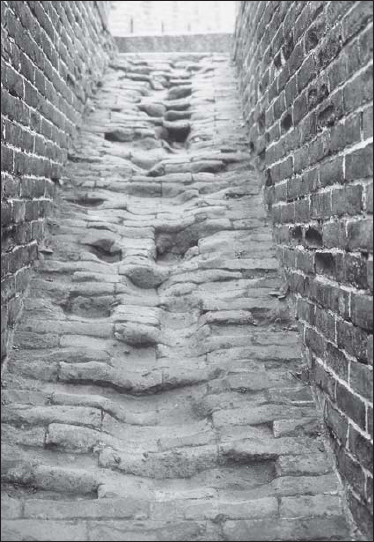

Nevertheless, the deep depressions worn into the flights of steps that lead from the fields to the Great Wall’s battlements show that considerable activity went on along the Wall. Much time would be spent bringing in supplies, cleaning and repairing weapons and tower maintenance. When defence was required bows, particularly crossbows, and later guns were used.

This worn staircase on to the walkway at Mutianyu shows how much the Great Wall was used over the centuries.

Spears, halberds and swords were the main edged weapons with which to repel a raiding party, while stones could be dropped from the apertures along the parapet. The zhang qiang (transverse walls) provided a useful series of defensive barriers if an enemy gained access to the walkway, and even if some towers might be lost, the strongest towers with their retractable rope ladders would provide a formidable barrier until reinforcements arrived. An elaborate variation on the rope ladder, although one apparently used only in the detached towers, was a wooden platform on which one man could stand, fastened by two long ropes to two winches which would be wound up to take him to safety.

A Ming dynasty ‘recommended equipment list’ for a five-man crew in an individual watchtower may not have differed much other than in scale for the garrison of a tower on the Great Wall. It lists a bedstead, a fireplace with a cauldron, one water jar, five cups and five saucers, rice, salted vegetables, three ‘big guns’, and finally wolf dung and a brazier for signalling, a vital duty to which we will now turn.

One of the most vital functions of the towers on the Great Wall was signalling, an importance underlined by the fact that whenever the idea of a long wall fell into abeyance individual beacon towers continued to be built and used. Some of the most abundant and valuable data for military life on the Great Wall may be obtained from the numerous references to signalling stations.

During the Han dynasty, when towers consisted of rammed earth, signals were not made from a brazier on top of a tower but by using a basket containing dry wood and grass. The basket was fastened to the end of a pivoted sweep up to about 10m long. As the sweep was mounted on top of a tower that may have been over 15m high the beacon could be swung high into the sky when raiders were spotted. At night it would be the flames given off that were recognized. By day adding wolf dung to the combustible mixture produced thick black smoke.

Contemporary documents describe the signalling towers as surrounded by their own defensive barriers, and including living quarters for the crews and stabling for their horses. The size of the crew depended upon the importance of the site. Those immediately adjacent to the Han Great Wall would have been well defended. Additional duties included operating a courier system (which had to replace signals in the case of fog), agricultural work and keeping records of observations and actions taken. Under the Han there were two types of signals required: a regular ‘all clear’ and a series of warning messages. Should the regular signal fail to appear, the crew of the next tower in the chain would investigate the matter. If the tower came under attack, two signals meant that the enemy numbered 20 men, three signals meant a raiding party of up to 100 men. It has been estimated that 10,000 men would have been needed to man the extensive network of Han beacons, watchtowers and sections of wall, let alone their reserves and support personnel.

Under the early Ming an even more elaborate system of signal towers was created. Liaodong, for example, had no less than 2,710 towers in all. A text by General Qi Jiguang mentions the use of wolf dung for smoke signals, but notes that it was difficult to obtain in the south, and as the account goes on to mention a black flag and a white flag, cannon and some lanterns we may presume that these items provided an alternative way of signalling.

One other vital function carried out from the security of the Great Wall and its towers was the gathering of intelligence. This could take the form of mounted patrols or the more hazardous method of spying deep within the Mongol territories. In 1449 some agents even penetrated the Mongol camps and carried out assassinations. In 1450 a group entered a Mongol camp and started fires in various locations just to let the Mongols know that the border was on the alert.

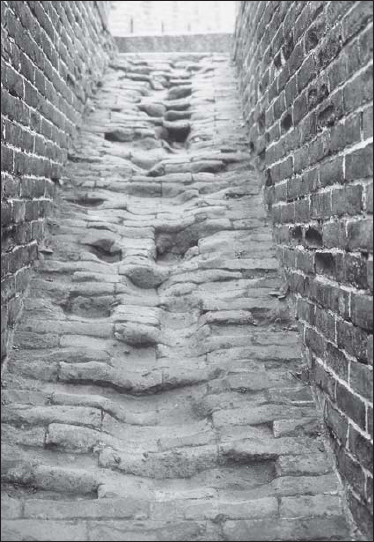

One of the most valuable functions of the towers on the Great Wall was signalling. Fire would be used by night. Black smoke, produced by adding wolf dung to the combustible mixture, was used during daylight. This illustration is in the Great Wall Museum at Huangyaguan.

Various forms of cannon were mounted on the Ming Great Wall. The Mongols, it was said, were afraid of ‘magical guns’ – a somewhat optimistic statement in view of the Yuan dynasty’s enthusiastic adoption of firearms. The Yuan were in fact the first rulers in the history of the world to make use of metal-barrelled cannon, which appeared in Chinese sieges decades before similar weapons were being employed in Europe. These primitive Chinese cannon were clearly valued as defensive siege weapons, because a Ming edict of 1412 ordered the stationing of batteries of five cannon at each of the frontier passes as a form of garrison artillery. Some designs of Chinese cannon saw very long service. For example the ‘crouching tiger cannon’, which dates from 1368, was still being used against the Japanese in Korea in 1592. It was fitted with a curious loose metal collar with two legs so that it needed no external carriage for laying. Another was the ‘great general cannon’, of which several sizes existed, and an account of 1606 notes a range of 800 paces. The enthusiastic description continues:

Defending a wall using crossbows and spears. This is not actually the Han dynasty Great Wall but the defeat of the ‘terracotta’ army of the Qin emperor by Xiang Yu in 207 BC. Nevertheless, we see similar weapons being used from behind similar rammed-earth walls.

A single shot has the power of thunderbolt, causing several hundred casualties among men and horses. If thousands, or tens of thousands, were placed in position along the frontiers, and every one of them manned by soldiers well trained to use them, then [we should be] invincible.

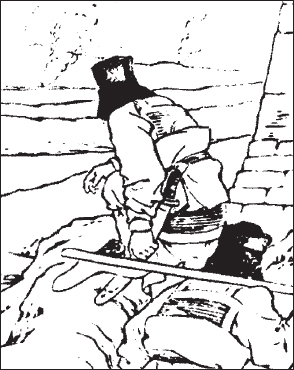

The curious zhang qiang (transverse walls) are unique to the Great Wall at Jinshanling. They extend halfway across the walkway and provided defences against a sudden occupation of a section of the wall by a raiding party.

A partially ruined section of the Great Wall lying beyond the much-visited Badaling section. (Photograph by Ian Clark)

From the early 16th century onwards a different type of cannon entered the Chinese arsenal, and this one came from Europe. It was known as the folang zhi, which means ‘Frankish gun’, ‘the Franks’ being a general term for any inhabitants of the lands to the west. Instead of being rammed down from the muzzle, ball, powder and wad were introduced into the breech inside a sturdy container shaped like a large tankard with a handle. A metal or wooden wedge was driven in behind it to make as tight a fit against the barrel opening as could reasonably be expected, and the gun was fired. The main disadvantage was leakage around the muzzle and a consequent loss of explosive energy, but this was compensated for by a comparatively high rate of fire, as several breech containers could be prepared in advance. The description of an early folang zhi notes that it weighed about 120kg. Its chambers, of which three were supplied for rotational use, weighed 18kg each, and fired a small lead shot of 300g. In 1530 it was proposed that folang zhi should be mounted in the towers of the Great Wall and in the communication towers.

A cannon emplacement on the Great Wall at Mutianyu with a reproduction iron cannon. Real cannon would not have been cemented into their carriages!

By 1606 the breech-loading principle had been extended to larger-sized guns, and one called the ‘invincible general’, which was favoured by General Qi Jiguang, weighed 630kg, could fire grape shot over 60m and was mounted on a wheeled carriage. Another European cannon came China’s way very early in the 17th century, when a huge gun, larger than any seen in China up to that time, was obtained from a visiting European ship. It was 6m long, and weighed 1,800kg. Because of its origin the weapon was christened the ‘red (-haired) barbarian gun’, and it was remarked that it could demolish any stone city wall. The Ming were so impressed that the Portuguese in Macao were invited to send artillery units north to Beijing to defend the capital against the Manchu threat, and the Jesuit priests who accompanied them were set to work in setting up a cannon foundry, which they did with some success.

The Ming attributed their success in holding the Manchus at bay outside the Great Wall to their superiority in firearms of all sorts. In 1621 ‘the cannon were brought to the frontier of the empire, at the borders with the Tartars (Manchus) who having come with troops close to the Great Wall were so terrified by the damage they did when they were fired that they took to flight and no longer dared to come near again’. This was something of an exaggeration, but Nurhachi, the founder of the Qing dynasty, made great efforts to obtain guns of his own, and by 1640 it was reported that his successors had forged 60 cannon ‘too heavy to carry round’. Other rebels against the Ming had firearms too, including Li Zicheng, who eventually overthrew the dynasty.

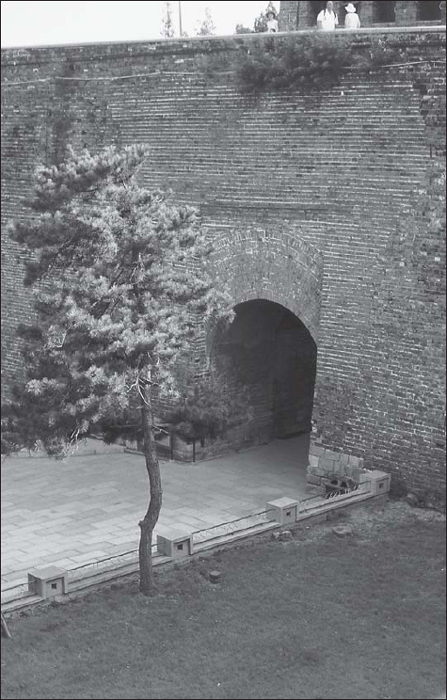

Looking down into the enclosed courtyard of the First Pass Under Heaven at Shanhaiguan we see the narrow tunnel that was so well guarded.