• 1 •

FOR WHOM THE

BELLS TOLL

A 41-inch bust and a lot of perseverance will get you more than a cup of coffee—a lot more.

—JAYNE MANSFIELD

[Breasts] are a body part that we didn’t start out with … whole new organs, two of them, tricky to hide or eradicate, attached for all the world to see … twin messengers announcing our lack of control, announcing that Nature has plans for us about which we were not consulted.

— FRANCINE PROSE,

Master Breasts

IF THERE’S ONE THING STARLETS LIKE JAYNE MANSFIELD AND Mae West understood, it was the power of their ample endowments. In her 1959 memoir, Goodness Had Nothing to Do with It, West writes that beginning in her teens, she regularly rubbed cocoa butter on her breasts, then spritzed them with cold water. “This treatment made them smooth and firm, and developed muscle tone which kept them right up where they were supposed to be.” West has good company in doling out ridiculous breast-enhancing tips. On the Internet, you can find creams, pills, pumps, pectoral exercises, even a YouTube video on how to master the boob-inflating “liquefy tool” in Photoshop.

In our culture at least, big breasts get a lot of attention. So I’m told. I display, or rather, don’t display, the traditional average American size, a B cup.1 Women I know tell me that having large breasts is like walking around with a neon sign hanging around their necks. Men, women, small children, everyone stares. The eyes linger. Some men pant. It’s not surprising that some anthropologists have called breasts “a signal.” Breasts, they say, must be telling us something about how fit and mature and healthy and maternal their owner is. Why else have them?

All mammals have mammary glands, but no other mammal has “breasts” the way we do, with our pleasant orbs sprouting out of puberty and sticking around regardless of our reproductive status. Our breasts are more than just mammary glands; they include a meaty constellation of fat and connective tissue called stroma. To be functional for nursing an infant, a mammary gland need fill only half an eggshell. Big breasts are not required. Along with bipedalism, speech, and furless skin, breasts in their soft stroma-filled glory are one of humanity’s defining characteristics. But unlike bipedalism and furlessness, breasts are found in only one sex (at least most of the time). And those kinds of traits, as Darwin pointed out, often evolved as sexual signals to potential mates.

But signals of what, exactly? And does this explain how and why humans won the boob lottery? Many scientists seem to think so, and they have devoted large chunks of their careers to answering these questions. One thing is clear: it’s rather fun trying to find out. It’s not especially hard to design studies showing that men like breasts. What’s much trickier is proving that it actually means anything in evolutionary terms.

I was hoping the answers might lie with the creative experiments of Alan and Barnaby Dixson, a father-son team of institutionally supported breast watchers. Both based in Wellington, New Zealand, together they’ve published papers on male preferences for size, shape, and areola color and on female physique and sexual attractiveness in places such as Samoa, Papua New Guinea, Cameroon, and China. Alan, a distinguished primatologist and former science director of the San Diego Zoo, brings a specialty in primate sexuality to their shared project, while Barnaby, a newly minted Ph.D. in cultural anthropology, has a knack for computer graphics and a fresh zeal for fieldwork.

I first met Barnaby on a blustery fall day in Wellington. At twenty-six, his curly auburn hair falling around the collar of a fisherman’s sweater, he was very earnest. He walked around with a distracted air and wrinkled brow, and often misplaced things, such as parking receipts. It’s not easy being a sex-signaling expert. “Sometimes people think I’m using the government’s money to look at breasts. They misunderstand what we do,” said Barnaby, who’s tall and gangly and speaks with a crisp British accent. As Barnaby pointed out, in places like Samoa, which is now very missionized, it can be a delicate matter asking men to describe which types of breasts they prefer. He said some men think he’s “a perv” and get very angry. He avoids men who have been drinking. And in the academic world, grant money can be hard to come by when there are things like breast cancer research to fund. “I probably should have been a doctor,” he said. “But I’m quite squeamish really.”

Barnaby’s latest digital experiment employed an EyeLink 1000 eye-tracking machine and a suite of specialized software. The sixty-thousand-dollar piece of equipment lives in a small, nondescript room labeled “Perception/Attention Lab” in the psychology department at Victoria University. It looked like something you’d find in an optometrist’s exam room. You place your chin in the chin cradle and your forehead against the forehead rest. Then you look through little lenses. Instead of seeing an alphabet pyramid, though, your eyes meet images of naked women flashing on a computer screen. If all eye exams worked like this, men would surely get their vision screened in a timely fashion.

On the day I visited the lab, an ecology graduate student named Roan was game to volunteer. Wearing jeans and a baggy T-shirt, he patiently looked through the eye-tracker as Barnaby calibrated the machine. Then Barnaby explained the test. Roan would be looking at six images, all of the same comely model, but digitally “morphed” to look different. Roan would have five seconds to view each image, and then he’d be asked to rank it on a scale of one to six, from least attractive to most, using a keyboard. The images would have smaller and larger breasts and various waist-to-hip ratios. These two metrics, the breasts and the so-called WHR (essentially a measure of curviness), are the lingua franca of “attractiveness studies,” which is, believe it or not, a recognized subspecialty of anthropology, sociobiology, and neuropsychology. The theory is that how males and females size each other up can tell us something about how we evolved and who we are.

The eye-tracker doesn’t lie. It would show exactly where on the body Roan was looking while making up his mind. As Barnaby had explained to me earlier, the machine would measure the travel of Roan’s pupils within one-hundredth of a degree, and would record how long his gaze lingered on each body part. “The beauty of the eye-tracking machine is that it allows you to get some measure of behavioral response. You can measure, literally, the behavior of the eye during attractiveness judgment,” Barnaby had said.

Roan began staring and ranking. The whole thing took a couple of minutes. He looked a little flushed when it was over.

He stuck around to see how he did. Barnaby called up some neat graphics and computations. A series of green rings overlay the model; they represented each time Roan’s eyes lingered for a moment. Some of the rings were on her face, a few on her hips, a whole bunch on her breasts. Barnaby explained them as he reviewed the data. “He starts at the breasts, then looks at the face, then breasts, then pubic region, midriff, face, breasts, face, breasts. Each time the eye rests longer on the breasts.” Roan spent more time gazing at the breasts than elsewhere during each “fixation.” He rated the slimmer images with large breasts as most attractive.

In other words, Roan behaved just as most men do, and just as Jayne Mansfield knew he would. She could have saved Victoria University a chunk of change.

Barnaby’s eye-tracker results may be obvious, but to a scientist, data are key. Barnaby was preparing to publish his study in a journal called Human Nature. He believed the work backs up a relatively well-accepted hypothesis that breasts evolved as signals to provide key information to potential mates. That’s why men’s eyes zoom in on breasts within, oh, about two hundred milliseconds of viewing an image. That’s milliseconds. “The overall theory is that youth and fertility are important traits when men and women in ancestral times were selecting a partner,” said Barnaby. “So it makes sense they’ll select for traits that signal mate value, youth, health, fertility.” He believes men find breasts useful. Because men liked these informative, novel, gently pendulous orbs—which originally sprang up in the accidental way all new traits do—they selected mates accordingly. The breasty women were the ones who mated most, or mated with the best males, and so the trait was passed down for all to behold. In the world according to Barnaby, that’s pretty much the end of the story.

I wondered whether Roan subconsciously sensed that cache of health and youth information in a few seconds of ogling.

“Do you tend to be a breast guy?” I asked him.

“Good question.” Roan is a South African who spends his academic time studying rhinos. “Yeah, but not majorly so. It’s not like I’m obsessed, like some guys I’ve met who tend to go on about it. But yeah, I definitely don’t have any problem with them.”

I couldn’t help feeling peeved by the real-world relevance of the eye-tracking study. A man looks at a woman’s hips and breasts for five seconds and decides whether or not to mate with her? Was that how it worked in our deep evolutionary past? Was it how it worked now? And even if it were, did it really explain why we have breasts in the first place?

“When you’re meeting a woman, you’re hopefully looking at more than just her breasts,” I said to Barnaby and Roan.

Roan blushed and laughed. “Of course! Cheers!”

“That’s an important point,” interjected Barnaby. “You’re not just going to stare at her breasts.”

“Some people do,” said Roan.

Barnaby felt a need to rescue the conversation. “This is an artificial experiment. It measures what you might call a first-pass filter, just things that are immediately apparent. Then later, when you’re meeting and talking, so many other things factor in, like personality, religious background, socioeconomic status.”

“Sense of humor?” I asked.

“Yeah,” said Roan. “Of course, of course.”

AFTERWARD, WE ATE LUNCH AT THE SMALL, CREEK-SIDE HOME IN the Wellington hills that Barnaby shared with his girlfriend, Monica, a Canadian graduate student studying bird behavior. She made a fantastic soup out of a roasted New Zealand tuber called kumara. A sign above the kitchen read, “Please do not feed the bear.”

It turns out I wasn’t the only woman whom Barnaby’s work made a little uncomfortable and self-conscious.

“Whenever Barny gives seminars on waist-to-hip ratios, all the women run home afterwards and measure themselves,” said Monica. (Barnaby’s studies and many others have established that men prefer a Marilyn Monroe–esque WHR of .7, meaning the waist is 70 percent the circumference of the hips. Some scientists hypothesize that this magic number represents an optimal level of health and hormones, but the significance of the WHR is highly controversial in the field.)

Barnaby looked mortified. “Yeah, well that’s unfortunate.”

“I measured mine,” offered Monica.

“How did it turn out?” I asked.

“I’m a .75.”

Barnaby himself doesn’t seem immune to his research. He wears, for example, a beard. In his cross-cultural anthropological studies, he has found facial hair to symbolize masculinity and authority. (His father, who teaches at the university and lives one town over with his wife, Amanda, and an eighty-pound English bulldog named Huxley, sports a bushy white mustache.)

Barnaby’s walls boasted several original Alan Dixson drawings, including one of a mandrill and one of a gorilla. Alan illustrates most of his own textbooks, while Barnaby supplies the computer graphics. Alan’s latest book is called Sexual Selection and the Origins of Human Mating Systems. In addition to their eight coauthored papers, they share a love of animals and a polite, diffident demeanor.

“Barnaby is like a mini-me of Alan,” said Monica, laughing. Born in England, the younger Dixson grew up in places like Scotland and West Africa, depending on his father’s posts. In Gabon, where Alan ran a primate center and studied sperm competition, Barnaby’s family had a pet monkey, a potto named Percy. Living closely among other animals made their behaviors, sexual and otherwise, seem perfectly normal. Barnaby’s older brother is also a scientist. His specialty is an enormous flightless cricket.

Both Alan and Barnaby believe studying mating behavior and sexual selection in primates can tell us much about our own reproductive organs. For example, men have relatively small testicles compared to other existing primates. Alan has written that this might indicate our early human ancestors were polygamous. (On this topic scholars vehemently disagree with each other. The field of evolutionary studies is a blood sport.)

To the Dixsons, enlarged human breasts, like giant testicles in chimps or the orangutan’s beard, are “courtship devices” born out of competition and selection. Large testicles produced more sperm, maximizing an individual’s chance that his genes, and not his rival’s, would penetrate the egg of a promiscuous female. The males with the biggest testicles had more descendants, who in turn had bigger testicles. The Dixsons believe beards and enlarged breasts, on the other hand, are seductive “adornments” advertising genetic quality. Those who attracted the best mates had fitter offspring and, ultimately, larger numbers of descendants, and so the traits persisted. This is the essence of sexual selection as posited by Charles Darwin.

“A lot has been written about what breasts might be telling a guy,” said Barnaby. “At its simplest, they’re telling the guy that this is a sexually mature woman. Beyond that, there are a lot of hypotheses. One that I find interesting, based on work on Hadza huntergatherers in Tanzania, is that there could be a profound preference among men for a nubile breast shape.” He explained that as women age and have more successive pregnancies (thus reducing her worth to a new mate), her breasts change. “I’m trying to find a nice way of saying it,” hedged Barnaby, “but age and gravity take their toll. The shape tends to lose its firmness and droops somewhat. This could be something that’s letting a man know about youth and fertility and potential reproductive output.” In other words, guys, go pursue someone a little more worthwhile, biologically speaking.

It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there.

The nuances continue. Large breasts sag more than small breasts, said Barnaby, so men likely prefer big ones because they are more “informative” of age. Other studies back up Barnaby’s hypothesis, some with real-life experiments. A few years ago in Brittany, France, a twenty-year-old actress of “average attractiveness” with relatively small breasts was given an unusual assignment: to sit in a bar while an undercover researcher recorded how many men approached her. Then she inserted enough latex padding into her bra to bump the cup size up to B and went to a neighboring bar. You can guess the third step: repeat with size C. She wore the same clothes in each bar, a pair of jeans and a tight-fitting sweatshirt. She was instructed to watch the dancing on the dance floor, but not to look at men along the edges. This was repeated for twelve nights over a three-week period.

When she wore the A-cup bra, she was asked to dance thirteen times. When she wore the B cup, she was asked nineteen times. And when her breasts grew to a size C? Forty-four dance cards.

In a similar experiment, Miss Elasto-chest tried hitchhiking by the side of the road, also in Brittany, at the height of summer and during the day. In her A-cup incarnation, fifteen men stopped; in her B cup, twenty men; and in her C cup, twenty-four men stopped. When the passing motorists were women, approximately the same number stopped for each cup size. Another study showed that waitresses with larger breasts get bigger tips.

Steven Platek, an evolutionary neuroscientist from Georgia Gwinnett College, showed college men pictures of breasts while he scanned their brains in an MRI machine. Not so surprisingly, he found the breast images triggered the “reward centers” in the volunteers’ brains. “Most of the images capture the attention of the male so much so that it will distract his mental and cognitive processes in ways that could be dysfunctional in other capacities,” Platek told me. The Urban Dictionary refers to this state as booblivious.

Okay, so men are distracted by breasts. All of this sounds familiar to us in Western cultures, but there are problems with making sweeping statements about evolution based on studies about male behavior in pubs. For one thing, I am still hung up on the nubility hypothesis, which might as well be called the sag hypothesis. But speaking from personal experience, I can report my breasts actually got bigger and fuller after pregnancy. I really can’t say they are sagging, not yet anyway. I am well past the age of what anthropologists call “peak reproductive value.” Does a man really need breasts to tell him a woman is getting on in years? Aren’t there more obvious signs that don’t require awkward social glances? And as anyone who’s been to a public shower or springtime college campus can tell you, there is an enormous, and I mean enormous, variety of breast sizes and shapes out there. I’m talking 300 to 500 percent differences in volume, and these are in women of roughly the same age. What other body part is so variable, I ask? If breasts were such important communicators, wouldn’t they be more on the same page?

Further complicating the picture, there is also great variety in men’s tastes. Barnaby conceded that male preferences aren’t as universal as he’d hoped. He expected all men to prefer breasts of a similar size—namely, big. But that doesn’t always happen. In his earlier data from the eye-tracker, which he published in Archives of Sexual Behavior, the same number of men preferred medium breasts to large breasts, and some men were most enthusiastic about small breasts. And these were all straight, white men from New Zealand. Other studies have shown that Azande and Ganda tribesmen prefer long and pendulous breasts, whereas the Manus and Maasai prefer more rounded ones. One study found that Western men prefer curvier women during a recession, perhaps for their suggestion of comfort and ample calories. In his own study, Barnaby found that men simply liked staring at all breasts, regardless of size or how attractive the image was rated.

If breasts serve as such a great signal of a woman’s fitness, so should the areola, posits Barnaby. Younger women who have never had children have lighter areolas, so Barnaby expected men to prefer lighter pigmentation when they rated images in another study. He was surprised to learn that many men like darker, postpregnancy areolar pigment. Similarly, data on preferences for areolar size were all over the map. And while most men seem to like breasts, in many places breasts are merely pedestrian. Not every culture has a Hooters. The nape of the neck is unbearably sexy in Japan. Bootylicious is where it’s at in parts of western Africa and South America. When my son was little, he used to mortify me by going around the house singing a Sir Mix-a-Lot song from the Shrek soundtrack: “I like big butts and I cannot lie.”

Barnaby knows about these inconsistencies, and they cause him some academic heartburn. But while he acknowledged the data are far from conclusive, he still thinks they hold up. “The amount of visual attention and the amount of evidence that men are attracted to breasts would lead you to think something is going on in evolutionary terms with mate choice and breast morphology.”

BARNABY IS JUST THE LATEST IN A LONG LINE OF SCIENTISTS WHO have been thinking about how the breasts evolved in step with the male gaze for at least half a century, ever since Desmond Morris published his famous and influential book, The Naked Ape, in 1967. (Morris, a British zoologist, is also known for choreographing the gestures and grunts of the actors in Quest for Fire.) In The Naked Ape, he attempted to explain to a popular audience why humans act the way they do. Describing a prehistoric life very much like the suburban dead-zone of the mid-twentieth century, Morris wrote how out of the Pleistocene emerged “Man the Hunter,” unique among primates, who came home after a hard day of stalking beasts and needed his hearth-bound woman to show him a stimulating set of knockers. Without them, he’d have little inclination to stick around and provision the family. (Never mind that hunter-gatherer women procured most of the daily food for their families; that research came later and Morris still has not adjusted his breast-origin hypothesis.)

Since Mrs. Mighty Hunter had to be constantly sexy for this scenario to work, she needed a big front-and-center sexual organ different from what all other primates who did not walk upright on two legs had. Those primates signal sexual readiness, their estrus, with swollen buttocks or labia. “Can we,” asked Morris, “if we look at the frontal regions of the females of our species, see any structures that might possibly be mimics of the ancient display of hemispherical buttocks and red labia? The answer stands out as clearly as the female bosom itself. The protuberant, hemispherical breasts of the female must surely be copies of the fleshy buttocks, and the sharply defined red lips around the mouth must be copies of the red labia.”

I may never again think of lipstick the same way.

Today, The Naked Ape reads like an embarrassing manifesto of male dominance, presented at exactly the same time the women’s lib movement was heating up. Just as Linnaeus appeared to be pushing a political agenda in naming us Mammalia (nudging women to act more maternal during the Enlightenment), perhaps Morris was too. On the other hand, maybe Linnaeus and Morris and the whole lot of them were really just breast men.

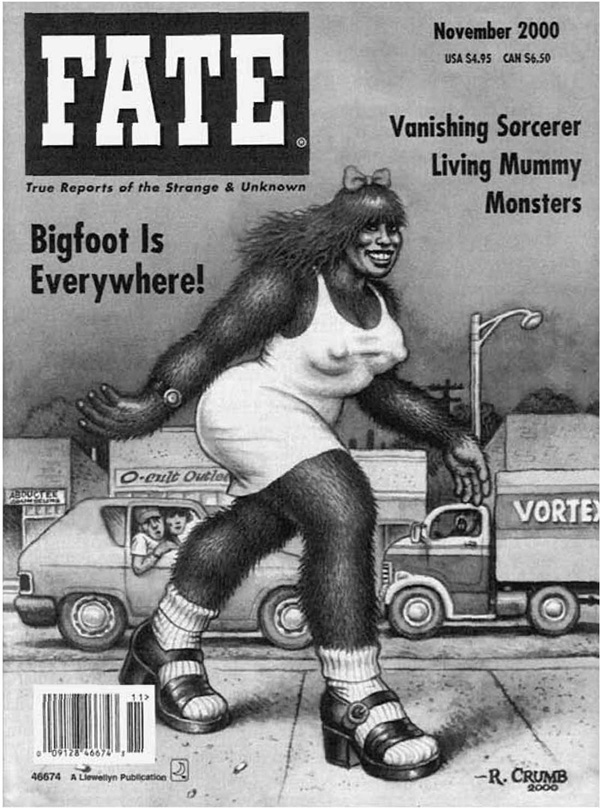

Clearly, many anthropologists love breasts. In textbook illustrations and museum dioramas, they always seem to depict the latest evolutionary “missing links” with breasts, despite zero fossil evidence for this. Ardi? Lucy? Breasts and more breasts. Even Mrs. Bigfoot is often drawn with a comely pair. We all know men like Morris; there are lots and lots of them. But there are also some leg men out there, like my husband, God bless him. In any case, the science of sexual attraction has been marked by fierce debate and bald accusations of cultural bias that continue to this day.

Try telling some feminist anthropologists that breasts exist because of men, and you might get whacked in the head by a rubber Australopithecus pelvis. Elaine Morgan, a Welsh writer, wrote an entire, rather delicious book refuting Morris and his ilk, called The Descent of Woman. In it, she thoroughly debunked the notion that the needs of the male drove every clever anatomical adaptation in human ancestors, including breasts. “I find the whole yarn pretty incredible,” she wrote. “Desmond Morris, pondering on the shape of a woman’s breasts, instantly deduces that they evolved because her mate became a Mighty Hunter, and defends this preposterous proposition with the greatest ingenuity. There’s something about the Tarzan figure which has them all mesmerized.”

Frances Mascia-Lees, a Rutgers University anthropologist, told me she thinks the scholarship over the past fifty years on breasts and attraction has been a colossal waste of time. “When you talk about the old guys, the same arguments are still being made. They will not die under any circumstance. But when it comes to finding a mate and having children, breast size does not matter, even though many advertisers and plastic surgeons might love us all to think so,” she said.

She pointed to a number of holes in the breasts-as-sex-signals theory of origin. If big, firm breasts tell a man that a woman is fertile and ready for sex, then why would her breasts be biggest and firmest when she’s already pregnant or lactating? Why is there such huge variation in human breast size and shape, and why are so many women with tiny breasts spectacularly successful at nursing, childbirth, and child-rearing?

Although I hate to admit it, I couldn’t help wondering if Mascia-Lees herself has tiny breasts and if that had influenced her contrarian worldview. So I asked her, and it turns out she has the opposite problem. She’s a 36DD. When she entered graduate school in 1981, her department consisted of fifteen men and one woman. The American obsession with breasts was annoyingly evident. “Having big breasts meant you were highly sexualized by men,” she said. “It was a prickly issue for me trying to be taken seriously as an intellectual.” At the time, the Mighty Hunter theory was everywhere. He drove the evolution of the bigger brain, speech, social behavior, bipedalism, the use of tools, and so on. It rankled. It got her thinking. In a sweet-vengeance counter-scenario, Mascia-Lees and others instead argue that it’s just as likely the female drove these developments, through lactation and the unique demands of the human infant. Just suppose for a moment, gentlemen of the academy, that breasts evolved because she needed them, not because her club-wielding cave man did.

Mascia-Lees argues that breasts evolved through natural selection, not sexual selection. It seems perfectly reasonable, if not more reasonable, to suppose there was something about having breasts that increased the fitness of the woman and her offspring in what Darwin plaintively calls the “struggle for existence.” Male interest, if it even exists universally, was secondary. She posits that breasts helped increase a woman’s fat reserves, even if just by a few percentage points. In the poor or unpredictable environment of our early evolution (such as the open plains with their greatly fluctuating temperatures), those extra fat depots could have made the difference in being able to sustain pregnancy and lactation. Humans need to store more fat than other primates because they don’t have fur to keep them warm. On top of that, pregnant humans need to mobilize more fat to keep pace with their pudgy babies, whose big brains need specialized stores of long-chain fatty acids. Consequently, women’s bodies are designed in such a way that they don’t even ovulate unless a body-fat threshold has been crossed. On average, reproductive-age women store twice the fat that men do.

But why store fat in the breasts and not, say, the elbow? Mascia-Lees has a good explanation for this. Fat and cholesterol make estrogen. Mammary glands are filled with estrogen-sensitive cells. We have more estrogen than other primates simply because we’re relatively fatter. Here’s the sequence: we needed to be fatter at puberty and beyond to produce human infants; our fat made estrogen, and estrogen made our breasts grow because the tissues there are so attuned to it.

In Mascia-Lees’s account, breasts are merely “by-products of fat deposition.” She admitted her theory is not nearly as testable, or as sexy, as that of the Morris crowd. But that’s the point. “I’ve tried to show that my assumptions are more firmly grounded,” she said, “and not just the same cultural assumptions we have now projected back into evolutionary history.”

Maybe because I’ve never had the sort of chest that men stare at, I’m more willing to consider alternative theories of origin. And there are lots. One thing making it tricky is that, unlike the opposable thumb, breasts leave no fossil record. There’s no way of knowing exactly when the well-endowed rack appeared in human evolution. Was it before bipedalism or after? Before we lost our fur? Pretty much all of the theories accounting for breasts, Mascia-Lees’s and the Dixsons’ included, are best categorized as SWAG, scientific wild-ass guesses.

SINCE BREASTS ARE CATCHMENTS OF OUR COLLECTIVE AND individual fantasies, it makes sense that not even scientists are immune from their charms. When we consider the mysterious origin of this fine fleshy organ, breasts become easy metaphors for whatever we desire, from buttocks to political hegemony. One desert zoologist sees in breasts the camel’s hump, an adaptation that allows us to survive in arid climates through fluid and fat storage. To feminists, the breast story is a parable of self-determination.

There are plenty of other entertaining, if far-fetched breastorigin stories. Wrote Henri de Mondeville, the surgeon to King Philippe le Bel of France in the early fourteenth century, “The reasons why the breasts of women are on the chest, whereas other animals more often have them elsewhere, are of three kinds. First, the chest is a noble notable and chaste place and thus they can be decently shown. Secondly, warmed by the heart, they return their warmth to it so that this organ strengthens itself. The third reason applies only to big breasts which, by covering the chest, warm, cover, and strengthen the stomach.”

In 1840, one physician speculated that fatty breasts warm the milk and “enable women of the lower class to bear the very severe blows which they often receive in their drunken pugilistic contests.” He’d perhaps been reading a few too many Gothic novels.

More recently, an Israeli researcher posited that fatty breasts are needed to help the upright female maintain her balance. Otherwise, her fatty bottom would tip her backward. My sister-in-law says this is certainly the reason in her case.

Elaine Morgan, the Welsh critic, has buttressed her own breast theories with some astute anatomical observations. She notes that when our ancestors lost their fur, babies faced some new challenges. Other tiny primates cling to their mother’s fur from a very early age. Mom is free to swing from the trees and dig up ants, even while junior breast-feeds. No such luck for humans. We have to hold our little urchins, and the best place for that is the crook of our arm. Even then, though, the nipple still needs to come down a bit to baby. The pendulous breast came to the rescue. Then, once the human baby’s hands were free from clutching, they could gesture. An important form of expression evolved and helped make us who we are.

The whole enterprise is greatly assisted by a flexible, unmoored nipple. As Morgan puts it, the brilliantly shaped human breast “ensures that the nipple is no longer anchored tightly to the ribs, as they are in monkeys. The skin of the breast around the nipple becomes more loosely fitting to make it more manoeuvrable, leaving space beneath the looser skin to be occupied by glandular tissue and fat. Adult males find the resulting species-specific contours sexually stimulating, but the instigator and first beneficiary of the change was the baby.”

I can wholly affirm that it would be very awkward to breastfeed without a nice moveable feast of a nipple. British anthropologist Gillian Bentley of the University of Durham was nursing her own child when another anatomical light bulb went off: it was our skull shape that drove the ontogeny of rounded breasts. One of the major distinguishing features between us and other primates, indeed between us and most mammals, is our lack of anything resembling a snout. There could be a couple of reasons for this. One is that we have different jaw and teeth structures, the better for eating a varied diet, including cooked meats, which means we don’t need huge mandibles to rip apart raw flesh. Another is that we have humongous brains and, at birth, relatively large heads, five times the size of what you’d expect in a primate our size. But in order for newborns to get through our unusually narrow bipedal hips, their faces need to be flat, said Bentley. Flat faces and flat chests don’t work well together. Think of kissing a mirror; if the baby’s face had to smoosh against a flat chest, it wouldn’t be able to breathe through its nose. (Now here you might be clever and ask, as I did, Why didn’t evolution instead come up with a different place for the nose, say, near the ear? In fact, why are all mammal noses between the eyes and mouth? The answer has to do with our primitive, born-from-fish infrastructure, a template we’re not free to mess with. No doubt it was easier for our genes to tinker with the breast instead.) Thanks to round breasts, we can be smarter.

I started reading more about heads and necks, and I learned about a unique human feature called basicranial flexion. That’s how we bend where our neck meets our head, and it is different in us than in anyone else. Human babies, let’s not forget, cannot hold their heads up. We may be the only mammal that can’t do this. We have unusually big heads, and we also have necks, the better for growing a laryngeal cavity so that we can speak. A newborn must be held in order to breast-feed (because we have no fur for him to grab), and his head must be supported, or else his delicate larynx tube, also called a neck, would break. All the more reason why it might be helpful to have a nipple that can come down to the baby. It’s a theory, but I like it: thanks to pendulous breasts, we can speak.

Other primates also have fleshy breasts while nursing, but without the permanent fat pad they’re not quite as enlarged or as round. What’s appealing about these woman-centered theories for the breast is that they make some attempt to understand how the organ actually works. The boobs-for-men theories do not.

This is what flummoxes Dan Sellen. He’s an anthropologist specializing in nutrition and ecology at the University of Toronto. “Most anthropologists don’t study the breast. They have no idea what it does,” he told me. “There’s a whole industry of folks looking at mate choice, and sure, breasts attract males, but that’s different from saying their primary function is to attract mates.” Furthermore, he says, “it seems really odd that of all the mammals who have mammary glands, we’d be the only one where the appendage is sexually selected. That would be adding a new function to the breast that’s absent from every other mammal.”

One could argue that it doesn’t really matter why we have breasts. We have them, we love them, they can be useful. “They’re pretty, they’re flamboyant, they’re irresistible,” wrote Natalie Angier in Woman: An Intimate Geography. “But they are arbitrary, and they signify much less than we think.”

But it does matter because, as we’ve seen, the origin stories wag long political, sexual, and social tails. Beliefs about the origins— and thus “purpose”—of breasts can even influence their health and functioning. It’s not just the feminists who are down on the sexual selection stories. Sellen is also, because, as he put it, oversexualizing the breast detracts from infant health and contributes to body image problems in young women. It’s hard enough to get women to breast-feed as it is. “If we keep reinforcing that breasts are exclusively for sex, we’re always undermining the idea that breast-feeding is normative and normal and should be supported. Look,” he said, “the reason humans have a slightly different breast structure has to do with delivering essential nutrients.”

As a specialist in infant nutrition, Sellen acknowledges his own biases. But the ones governing the work of the Dixsons and the other Morris descendants are stronger, he argues; in fact, they’re rooted in human nature. “Humans will make anything sexy. We can transfer some kind of sexiness to any trait.”

“Like bound feet?” I asked.

“Exactly,” he said. “In cultures that start to hide women’s bodies, that can explain why men are attracted to these traits. With breasts, men are just loading culturally a set of symbolizations onto something that really evolved for more direct reasons. We’ve got to be more scientific about it.”

THESE ACADEMIC FISTICUFFS WERE VERY MUCH ON MY MIND IN Wellington. On my last morning in town, I joined Barnaby and Alan Dixson for coffee. Alan was wearing a pink button-down shirt, suspenders, and a tan blazer. A Maori fishhook made from cow bone hung from a cord around his neck. He was part gracious Englishman, part eccentric Englishman. With his bushy mustache and slightly wild white hair, he reminded me of some of the primates he has spent so many years studying.

I asked Alan if he thinks it is possible that natural selection, not sexual selection, was driving the evolution of breasts. “I think the two went lockstep,” he answered judiciously. “Laying down the fat is naturally selective, because you need it. Then it becomes a question of where to put it. If you’re a dormouse, you put it in your tail. If you’re a mandrill, you put it in your ass.” Now the coffee was kicking in, and engaging professor mode was fully launched. “If you’re a human, and you put it in your chest, then maybe it’s sexually selected too, because in younger women, you’d have the appearance of healthy physiognomy. Men might prefer women with these attributes. We’re talking about a dynamic process. We’re not talking about the peacock’s tail, which is no bloody use at all. We’re talking about something that displays underlying health and well-being. I imagine there’s something to do with more than just lactation and pregnancy. I imagine breasts have something to do with displaying readiness for reproduction.”

“Yes,” mused Barnaby, hunkering over his espresso and wrinkling his brow again. “These things may be linked together. It’s a fair point.”

Ah. It seems we’d arrived at a happy medium. I could go home now. Except, for some reason, I still found myself not altogether satisfied. The more I thought about it, the less it seemed that sexual and natural selection of the breasts arrived in lockstep. In fact, I became increasingly convinced that breasts have been categorically miscast in modern history.

I kept thinking as my plane thrummed out over the Pacific, which long ago men and women crossed in rickety dugouts following their human dreams of migration and survival. Then, as for all of our history on this planet, they fell in love or in lust, and everyone who could have children did.

What if instead of men selecting breasts, the breasts selected the men? It’s possible that once upon a time, Early Man loved lots of different specimens of Early Woman, some with no breasts, some with small breasts, some with hairy breasts, whatever. Man, as we all know, is sometimes not that picky. Then, for the reasons described earlier—fat deposition, cranium shape, the development of speech, and the long neck—the women with the enlarged breasts and their infants gradually outlasted the others. That is, after all, the way natural selection works.

Consequently, the people who could talk and sing and have the biggest, best-fed brains were the ones born of women with breasts. It makes perfect sense that we would grow up to appreciate and enjoy breasts, eventually putting pictures of them in eye-tracker machines in universities.

Perhaps, all along, the breasts were calling the shots.