• 12 •

THE FEW. THE PROUD. THE

AFFLICTED: CAN MARINES SOLVE

THE PUZZLE OF BREAST CANCER?

Do unto those downstream as you would have those upstream do unto you.

—WENDELL BERRY,

Citizenship Papers

EVEN ITS NAME SOUNDS JAUNTY: CAMP LEJEUNE. SIGNS posted along the Marine Corps base in coastal North Carolina pointed the way to archery and bowling. The Burger King on Holcomb Boulevard advertised frozen fruit drinks. I half expected to see a pickup game of Capture the Flag. For a moment, I thought it looked like summer camp, until I realized it’s the other way around. The traditional American summer camp model is based on the military. Think about it: the uniforms, mess hall, reveille, all those games of conquest.

People don’t live at Camp Lejeune, they live “aboard” it. Home to some 150,000 marines and sailors and their families, the base covers 236 square miles. In its outer reaches lies evidence of the more serious pursuits of the Second Marine Corps Division. There is, for example, the (former) Live Hand Grenade Course, the Fortified Beach Assault Area, and, of course, the Flame Tank and Flame Thrower Range. (Don’t think that one will be coming to Camp Wigwam any time soon.) These sites may have helped keep America strong, but they have also helped keep it sodden with volatile organic compounds. All of these zones, plus dozens of others on the base, are currently marked on the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Priority List—otherwise known as Superfund.

Unfortunately, the base’s worst historic contamination overlay much of its drinking water supply for at least three decades, from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s. Nicknamed “camp sloppy,” the base is made up of a big series of linked wetlands, aquifers, and the lazy New River flowing down the middle of it, all tilted toward the ocean. In one industrial area of the base known as Hadnot Point, fuel tanks silently dribbled or poured close to two million gallons of gasoline into the groundwater, forming a plume of petroleum now believed to be fifteen feet thick and half a mile wide. Atop it all sat well number 602, which in 1984 helped supply water to eight thousand people and yielded a reading of 380 parts per billion of benzene. This is seventy-six times the legal limit for benzene, a known human carcinogen.

Hadnot Point was known as a “fuel farm”—essentially the base’s gasoline depot—and it’s also where the Second Maintenance Battalion fixed tanks, jeeps, and other fleet vehicles. Beginning in the 1940s, it also held, in addition to gasoline, leaking storage tanks of industrial chlorinated solvents, notably trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE) used for degreasing machinery. Up the road sat the base’s disposal yard, where these solvents and others were dumped or buried. Some wells were more contaminated than others, but water from many wells was routinely mixed and then distributed to numerous houses and barracks from central water treatment plants.

The legal drinking water level for TCE and PCE, long considered probable carcinogens, is 5 parts per billion. That level, though, wasn’t established until 1989. Although the military knew there was a potentially hazardous contamination problem by 1982, it did not routinely check the levels here until late in 1984. At that time, analysis from one well revealed 1,600 parts per billion of TCE. Tap water at the elementary school contained 1,184 parts per billion. That is five times the levels recorded in the poster-child-city of water pollution, Woburn, Massachusetts, site of the book and film A Civil Action.

Camp Lejeune, in addition to being the “home of the Marine expeditionary forces in readiness,” now enjoys distinction as having had the most contaminated public drinking water supply ever discovered in the United States. Over the decades, 750,000 people drank it, bathed and swam in it, and inhaled its vapors.

The base also happens to form the center of the largest cluster of male breast cancers ever identified. We know this thanks not to the U.S. Marine Corps or even the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), an arm of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that is tasked with assessing the health effects of the contamination. We know this because of one man with the disease and an Internet connection, Michael Partain. He calls himself Number One.

Partain, a father of four and an insurance claims adjuster in Tallahassee, Florida, was diagnosed with cancer in his left breast in 2007, at the age of thirty-nine. He underwent a partial mastectomy and eight rounds of chemotherapy, and then developed “gonadal failure,” or an inability to produce testosterone. This was tough business for the son of a marine. “I never even knew men could get breast cancer,” said Partain. “I kept thinking, what did I do to win this lottery? I never drank or smoked. I liked backpacking and Boy Scouts. There is no history of breast cancer in my family.”

Not long after Partain was diagnosed, his father called him and told him to turn on the TV. There was a news report about the pollution at Camp Lejeune and its possible links to leukemia and other diseases. It was the first either man had heard of the contamination. Partain had been conceived and born on the base. “I knew right away I’d been exposed. I figured if this was the cause of my cancer, I wouldn’t be the only one,” he said. Partain went public with his diagnosis in the local media. Soon after, he got a call from a preacher in Alabama. He’d lived as a child in the same neighborhood as Partain, and at the same time. The preacher became Number Two.

Partain started Googling around for male breast cancer, and soon he found a photo of another man with the disease in Michigan. “His chest was half gone,” recalled Partain, “and his Marines uniform was draped over his arm. I was like, holy shit.” Before long, he’d found twenty men with breast cancer and ties to Camp Lejeune. CNN ran a story on them and their conviction that their disease was linked to contaminated drinking water on the base. Overnight, twenty more men contacted Partain. Soon there were fifty.

As of this writing there are seventy-one of them, and the number goes up virtually every month. (There are also plenty of women around who lived on the base and have breast cancer, but what else is new?) Is there really a link between the men’s cancers and the drinking water at Lejeune? Although some two hundred chemicals have been found to make mammary tumors grow in lab animals, it’s been extremely difficult to link chemicals to the disease in humans. Many experts say there is only one proven environmental cause of breast cancer, and that’s radiation. If new insight emerges from studying men like Partain, it could profoundly alter the way we view environmental health, and breast cancer in particular.

In the Western world, the incidence of breast cancer has grown in both men and women between 1 and 2 percent a year since 1960 (with the exception of a short-lived dip in women’s rates in the last decade), although it is still very rare in men. For every one hundred women who get breast cancer, only one man does. But ironically, it may be the men who help solve the puzzle of this disease. In looking for a link between breast cancer and chemicals, it’s much simpler to study men than women. Men’s risk factors aren’t complicated by such things as age at puberty, reproductive life history, and hormone replacement therapy. They’re just guys with a very rare disease, and rare diseases are easier to trace to environmental exposures. This cluster, unlike so many others, could prove statistically significant.

“We stick out like a sore thumb,” said Partain.

FOR ALL THE PERSONAL TRAGEDY CAMP LEJEUNE MAY HAVE caused an untold number of marines and their family members who have suffered from childhood cancers, birth defects, miscarriages, and adult diseases, the saga may prove a tremendous boon to scientists. Many of them gathered one recent summer day in Wilmington, North Carolina, for the twentieth meeting of the Community Action Panel, a committee of experts and local activists put together by ATSDR. The panel, one of several centered on Superfund sites around the country, meets four times a year to discuss the state of the science and any concerns that community members have. Thanks to active public participants, researchers found out about the massive benzene plume. It’s also because of the participants that male breast cancer, along with a number of other health problems, is now being studied by the agency.

Partain sits on the community panel, and so does a former drill sergeant named Jerry Ensminger, whose daughter, Janey, died of leukemia in 1985 at the age of nine. Two other panelists were notably absent, one suffering from battle-related post-traumatic stress disorder and the other recently dead of parathyroid cancer. Ensminger, bullish and compact, plays Calvin to Partain’s more measured Hobbes. Ensminger and Partain were the two lead characters of a recent documentary titled Semper Fi: Always Faithful, about the former Lejeune residents and their battle against the military for truthful information and health-care benefits.

“You’re wearing cowboy boots,” Partain said to Ensminger as they walked across the local campus parking lot to the meeting.

“That’s for kicking some ass,” Ensminger replied.

After a round of introductory remarks, in which Ensminger lit into the U.S. Marine Corps for sending only a silent observer to the meeting, federal epidemiologist Perri Ruckart reviewed ATSDR’s work to date. One health study performed by the agency in 1998 pointed to an association between the drinking water and male babies born smaller than expected. But in light of new (and more damning) evidence of contamination, the findings are now being reanalyzed with updated water modeling data. Several other important studies are ongoing, said Ruckart. These include a study of birth defects and childhood cancers in children born on the base, an overall mortality study of marines who lived there during the contamination, and a morbidity study that will canvass three hundred thousand former residents and base workers for illnesses. These studies will compare results with a similar but unexposed population from Camp Pendleton, a marine base in the state of Washington.

As Ruckart and her colleague Frank Bove had explained to me earlier, these are classic epidemiological studies, called case-control studies, which compare similar populations exposed to different things to see if one group is sicker. They’re not perfect because researchers must rely on high percentages of people to enroll in the studies. If only sick people from Lejeune choose to answer questionnaires, that’s called selection bias, and it can skew results. The ATSDR researchers won’t have to rely on participants to tell the truth, as they’ll laboriously confirm all medical diagnoses. These studies take years and cost tremendous amounts of money. The Lejeune studies will cost upward of $20 million. (Cleaning up the base is expected to cost more than $200 million.)

When they do work, health studies like these can be informative and (eventually) have a dramatic influence on public policy and medical practice. A case-control study is how researchers first reliably linked smoking to lung cancer. To date, the most revealing human cancer studies have been occupational ones, in which workers were known to be exposed to a particular chemical over a given length of time. Only a few general-population studies (as opposed to worker studies) have ever effectively proven a link between chemical exposures and cancer. Interestingly, though, two such studies also involved the solvents TCE and PCE, as well as other contaminants. In both Woburn (site of chemical and glue factories) and in Toms River, New Jersey (site of a dye-and-pigment plant), federal researchers concluded that the towns’ high childhood leukemia rates were caused by contaminated drinking water, although they could not untangle one particular compound as the villain. In Woburn, an unusual number of male breast cancers also appeared, but the number was too small—only a handful—to be statistically meaningful.

That is why Ruckart and Bove are looking so hard at Camp Lejeune, where hundreds of thousands of men were exposed and already a high number with breast cancer have come forward. If nothing else, the numbers to work with are bigger, and that means more reliable. As ATSDR director Christopher Portier explained it to me after the meeting, “If I take a coin and flip it ten times and get seven heads, that could be biased by chance or not. But if I flip it one thousand times and get seven hundred heads, then I guarantee you there’s an association. If there are real effects [to be seen at Camp Lejeune], then they will pop out in these studies where they looked marginal in others. We will do distinctly new science here.”

At one point during the question-and-answer session, a local woman asked, “What can you tell this man here about the cause of his health problems?” Portier answered, simply, “Nothing.” Even if the studies show a leak-proof link between cancer and the base’s water, those conclusions would not apply to individuals, only to the risks faced by the population as a whole. Try telling that to Partain, though, who points out that the average age of onset for male breast cancer is seventy. “Over half the men I’ve identified are under fifty-six years old,” he said. “That’s not right. I know what caused my cancer.”

Human nature is such that many of us easily believe causal links where they may not exist, especially when it comes to personal or familial tragedies. But the Camp Lejeune cluster has certainly raised the interest of academics and clinicians. Richard Clapp is an epidemiologist recently retired from Boston University who is serving as an outside expert on the community panel. He cautions that it may be years before the men get answers about the breast cancer. Even then the answers may be shrouded. While this is the largest cluster of male breast cancers ever found, there still might not be enough cases to get a strong signal in the data, he said. On the other hand, if an association does pan out, people will take notice. Most of Lejeune’s pollutants are not known to act as hormones, “so it would make it more of a pure chemical story, and you could say at least one type of breast cancer can be caused by chemicals,” said Clapp. “This should provide an opportunity to learn something. From an academic point of view, it’s good. For the men involved, it’s terrible.”

CAMP LEJEUNE MAY BE A VERY TROUBLED SPOT, BUT IT’S HARDLY unique. Now strongly suspected of causing human kidney cancer, TCE and PCE have been widely used both by the military and by many civilian industries. There are 130 military bases in the United States listed as National Priority sites under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or the Superfund law. TCE alone has been detected in at least 852 Superfund sites across the United States, and the chemical is the most frequently detected organic solvent in groundwater. It is suspected of being present in 34 percent of the nation’s drinking water supplies. TCE has primarily been used as a degreaser, septic-system cleaner, and dry-cleaning agent. In the what-were-they-thinking annals, TCE was also once a pet food additive, coffee decaffeinating compound, wound disinfectant, and even an obstetrical anesthetic. The Food and Drug Administration banned these uses in 1977, but regulators did not formally limit TCE and PCE in drinking water until the late 1980s. In September 2011, the EPA formally reclassified TCE from a “probable” to a “known” human carcinogen based on solid evidence linking it to kidney cancer and suggestive evidence of neurotoxicity, immunotoxicity, developmental toxicity, and endocrine effects.

PCE, sometimes called “perc,” is another chlorinated compound very similar to TCE. It is still used by most dry-cleaners, although the U.S. government is likely to stiffen regulations in the near future. Benzene, which is still a gasoline additive and smells vaguely sweet, was once used an aftershave. Now, according to Bradley Flohr, assistant director for policy, compensation, and pension services of the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, “we know for certain benzene is associated with acute myelocytic leukemia and other problems.”

Unfortunately, there’s more bad news: both TCE and PCE degrade into a potent toxic molecule, vinyl chloride. That too has been detected at some of the well sites. Vinyl chloride was one of the first chemicals ever designated a known human carcinogen by the U.S. National Toxicology Program and the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

But very little is known about what, if any, role these compounds play in breast cancer. Several studies have looked at breast cancers in both male and female workers exposed to these substances, but the results have been contradictory so far, and the study sizes have generally been very small. One recent European study found a doubled risk of male breast cancer in motor vehicle mechanics. “Petrol, organic petroleum solvents or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are suspect,” it concluded. Vinyl chloride has been linked to breast cancer in workers making PVC plastic. Another study found a very moderately increased risk of breast cancer among aircraft maintenance workers exposed to TCE. Some studies found that dry-cleaning workers who are exposed to PCE have a higher incidence of breast cancer, but other studies found a lower incidence.

A 1999 study looking at Danish women employed in other solvent-intensive industries found a doubled risk of breast cancer. Intriguingly, a set of studies looked at women on Cape Cod who had been unwittingly drinking public water laced with PCE from the lining in old pipes. Researcher Ann Aschengrau, an epidemiologist at Boston University’s School of Public Health, found that the women exposed to the highest levels of PCE had a 60 percent greater risk of breast cancer than those who were less exposed.

Aschengrau points out that both TCE and PCE are fat-loving compounds known to accumulate in breast tissue at high concentrations. It’s possible that special enzymes in breast tissue, notably in the ducts, might prevent the chemicals from breaking down. Once they’re sitting there, they could plausibly damage DNA in rapidly dividing breast tissue. As we saw in chapter 3, men have breast tissue also, and some men have more than others.

Just as it may seem ironic to have men lead the way down this particular path in breast cancer research, it is now the U.S. military—long resistant to notions of environmental health—that stands poised to become a pioneer, albeit a reluctant one, of environmental medicine. Of course, the armed forces have a long history of making its uniformed ranks sick. There was ionizing radiation from the Second World War through the cold war, Agent Orange during Vietnam, and, most recently, burn pits spewing dioxin and other compounds in the Iraqi outback. If you look at the increasing compensation claims being paid out to former Lejeune residents, it appears that TCE, PCE, and benzene will soon join the list of culprits. Every step of the way, Congress had to prod the Department of Defense to study the sicknesses and offer fair redress.

For the VA doctors, it continues to be an education. Terry Walters, director of the Environmental Agents Service at the Veterans Administration, came to the Wilmington meeting and spoke with me during a break about the challenges to her agency. “Exposure issues aren’t taught in med schools,” she said. “But for physicians within the VA, that should be our stock and trade. We should be experts in this. Getting that education out to Podunk or wherever is a big, big challenge. It’s not as mainstream as diabetes or cardiovascular disease. But every primary-care doctor should understand, if not specific information about benzene or TCE, then where to go to ask questions. My hope is that when a veteran comes in and says, ‘I was exposed to benzene,’ he or she won’t get a deer-in-the-headlights look from the doctor.”

HOW LIKELY IS IT THAT MANY OF OUR FRIENDS’ OR RELATIVES’ breast cancers are caused by an environmental agent? It’s virtually impossible to say. The American Cancer Society attributes only 2 to 6 percent of all cancers to chemical exposures, an estimate based partly on old and limited studies on occupational cancers. We learned about breast cancer and one environmental agent— radiation—from a large and unfortunate health experiment called the atomic bomb. For chemical exposures in a general population, though, confirmation is very difficult. We simply have too many mixed exposures over too long a time. “Epidemiology is what happens when you let all the rats out of the cages,” joked Frank Bove. There probably never will be a simple “smoking gun” in the search for causes of breast cancer in the general population. Our world and our genes are engaged in too complex a dalliance for that. After all, there are numerous types of breast cancer, dozens of cellular and molecular pathways that can lead to them, and probably an untold number of factors, including genes, that can alter those pathways.

We do know that there are some hot spots for breast cancer near hazardous waste sites and industrial facilities. In Long Island, New York, Marin County, California, and Cape Cod, Massachusetts, breast cancer rates have risen faster than in the rest of the nation. These locales share a legacy of industrial, agricultural, and military pollution. But other factors are also higher there and confuse the picture: all are wealthy enclaves, where women have children later, take more hormone therapy, and drink more wine. No wonder the epidemiologists get their pants twisted up.

In the President’s Cancer Panel report released in April 2010, the authors stated that cancers caused by chemicals have been “grossly underestimated.” The authors of the two-hundred-page report took an unusually bold stance in urging better oversight of the chemical industry. Coauthor Margaret Kripke, an immunologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, was once a skeptic on the topic of environmental disease. “I always assumed that before things were put on market, they would be tested,” said Kripke. “I learned that is not the case. I was so naive.”

Most of the major breast cancer organizations say there is no clear evidence that chemicals can cause breast cancer in humans. But in fact, there is little clear evidence that other things cause breast cancer, including the top favorites of obesity and smoking. If we look at all of the known red flags for breast cancer, such as reproductive and hormonal factors, family history, and radiation, they account for little over half of all breast cancers. Yet researchers have spent untold millions studying those things and very little studying chemicals. Perhaps it’s time, say many activists, to look deeper into chemical exposures, especially since damning evidence in animals and in occupational studies is slowly mounting. The existing research is troubling enough that in 2010, the Susan G. Komen for the Cure foundation broke ranks to shell out $1.2 million to the National Academy of Sciences for a major review of the science on environmental exposures and breast cancer. The result: while chemical causes seem “plausible,” better science is needed.

“A lot of data do suggest chemicals cause tumors in mammalian systems,” ATSDR director Portier told me after the community meeting in North Carolina. He believes the environment, defined broadly to include smoking, nutrition, and chemical exposures, causes most cancers. “We have good studies now, for example with identical twins, that suggest the numbers could be as high as 75 percent, he said.

“There’s a growing body of animal evidence and sporadic human evidence that things we’re exposed to across a lifetime can cause breast cancer,” agreed Marion Kavanaugh-Lynch, director of the California Breast Cancer Research Program, which funds environmental studies with proceeds from the state’s cigarette tax. “If we can identify these chemicals now, we can more easily avoid them,” she said.

IT’S TOO LATE FOR NUMBER TWENTY-THREE ON PARTAIN’S spreadsheet, who as an infant on the base attended a day-care center in the early 1980s that had been converted from a pesticide-mixing facility. (That was not one of our armed services’ smartest land-use decisions, even for its time.) He underwent a double mastectomy when he was eighteen years old. It’s too late for the handful of men Partain has found who are already dead. And it’s too late for Peter Devereaux, otherwise known as Number Seven. Pink is not a color he’d spent much time with. Camouflage, yes.

A native of Peabody, Massachusetts, Devereaux enlisted out of high school in 1980 and was stationed at Camp Lejeune until 1982. He was a field specialist in the Eighth Communications Battalion, and he lived in barracks that used drinking water from the Hadnot Point system. When he came home to Massachusetts after military maneuvers in the Philippines and Hawaii, he started working as a machinist. During the weekends, he pulled in extra income by landscaping, building patios, and moving heavy rocks and dirt around. He was also a serious athlete, running ultramarathons and boxing.

Now he can barely walk. Devereaux was so sick that he couldn’t attend the Wilmington meeting, so I called him afterward. He’s got a thick Boston accent. “In January 2008, I got breast cancer,” he told me on the phone from his home in North Andover. He was forty-five. “My hand had bumped into my chest in the morning. I figured I must have got elbowed playing hoop. Being a guy, you don’t even know about breast cancer. I never thought men could get it. But I told my wife, and she made me an appointment to see the doctor.” He was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer, meaning the cancer had spread to his lymph nodes.

Devereaux was dumbfounded.

“I felt like a freak. I got no breasts, how can this be? I’m a marine, I’m a bad ass, I work out all the time, I ate good, I exercised, stayed fit my whole life, never smoked or did drugs, and you try to figure out how can this have happened?” A month after Devereaux’s diagnosis, he received a letter in the mail from the U.S. Marine Corps at the behest of Congress. It stated that he might have been exposed to contaminated water while aboard Camp Lejeune, and it suggested that he and thousands of other marines register at a government website.

“When I got that letter in the mail, within one minute it made 100 percent sense to me that contaminated water was how I got breast cancer,” he said. Devereaux found a website started by marines and their families, and soon he was in touch with six other men with breast cancer, including Partain. He agreed to speak out in newspapers and on TV in hopes of reaching more men who may have been exposed at Lejeune. “I gotta let others know, man. I wish they’d let us know twenty years ago, and it could have been a different result for me.”

Like many men with breast cancer, Devereaux was diagnosed at a late stage in the disease. His treatment included a mastectomy and the removal of twenty-two lymph nodes, followed by radiation and fourteen months of chemotherapy. “It beat the crap out of me,” he said. In 2009, though, he learned the cancer had spread to his spine, ribs, and hips. It was metastatic. “There’s no cure this time,” he said. Despite being a tough guy, he finds some comfort in the breast cancer community. “You go into all these pink buildings and places for your mammograms and appointments. You’re this dude and all these women are looking at you. I meet these women, and they’re so much more open and honest and easy to talk to about emotions. Guys, all we talk about are football, eating, farting, and girls. So [these women] really helped. I felt a burden lifted. I wanted to move forward. My goal now is to raise awareness.”

But being an expert in combat hasn’t hurt. Devereaux wanted to fight the Marine Corps for health-care benefits and help other sickened veterans get them too. Vets can only receive benefits if they have a condition related to their service. He’d been out for over twenty years. Finally, after a two-year argument, he became the second male veteran with breast cancer to convince the government that his cancer was as likely as not linked to the water at Camp Lejeune. To qualify for service-related illness benefits, veterans must prove that an environmental exposure had a 50 percent chance of causing their problems. That may seem like a low bar, but of 3,400 total medical issues brought before the VA so far by former Lejeune residents, only 25 percent have been approved for benefits.

Not all the male breast cancer patients affiliated with Lejeune blame the base for their diagnosis. Take Bill Smith, a seventy-seven-year-old Floridian who was also treated for stage 3 breast cancer. I found him on the website set up by Ensminger and Partain. “I can’t say why I got this damned disease,” said Smith, who edited the base’s newspaper for two years in the late 1950s. “I lived a hard drinking, fun life. I worked the steel mills in Buffalo. I lived at Camp Lejeune. I don’t know where it came from. I can’t all of a sudden blame the Marine Corps. I don’t know and my doctors don’t know.”

What he does know is that the disease has reformed him from being a self-described swaggering SOB. “I’m not what I was,” said Smith, who after his time in the marines worked for many years in advertising on Madison Avenue. “I was a Mad Man. I was a user of women. I’m not even telling you how many times I was married. I’m not a swinger anymore, not a user. I appreciate women now, and they’re so much stronger than men. I went to support groups, I listened to them. I’ve had the privilege of entering a woman’s world.”

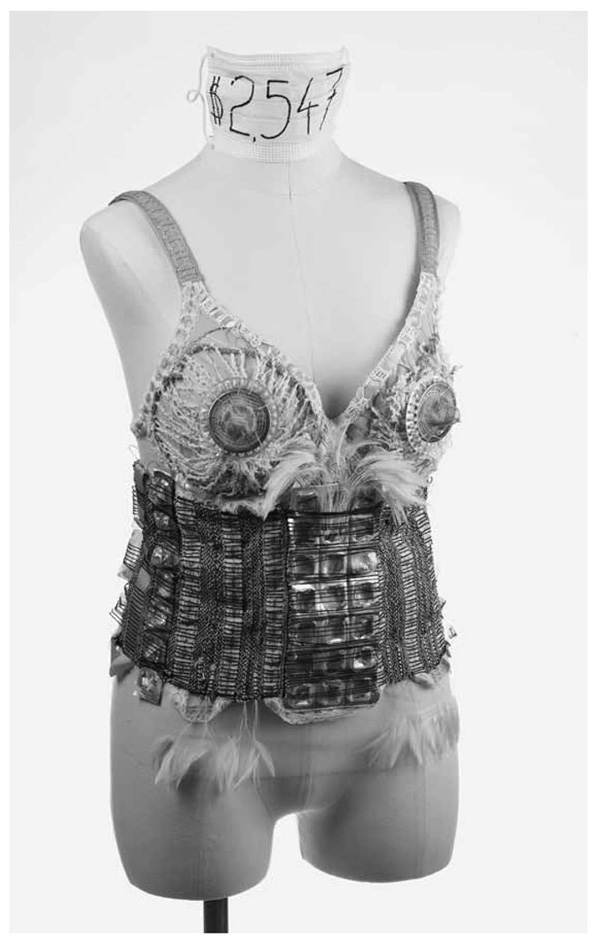

MOST MEN WITH BREAST CANCER, ESPECIALLY THOSE WHO WERE steeped in a military culture, don’t want to talk about it. Partain, though, is as chatty as a schoolgirl in spring. It’s why he’s such an effective spokesman for his cause. There’s nothing girly about his appearance. He describes himself as “a hairy beasty guy,” and it’s a fair assessment. Not long ago, he convinced Devereaux and a handful of other mastectomized men to pose, topless, in a calendar to benefit breast cancer research.

But underneath his affability runs a deep anger. He is angry that he has breast cancer, angry that the Marine Corps has not done more to apologize to these men or to compensate more of them for their disease. He has vigorously demanded that the Marine Corps turn over more data and notify greater numbers of former residents about the contamination.

As a journalist, I received permission to enter the base and get a tour of its extensive, ongoing $170 million (so far) cleanup mission, which involves everything from oil-eating bacteria to soil-vapor extraction to “pump and treat” stations that oxidize the water’s volatile organic compounds into more harmless molecules. Partain, though, said he is not even allowed aboard Lejeune because of standard security protocols. This makes him madder still. So before my base visit, Partain gave me a different tour of his own. We parked across the street, at a dry-cleaners on Highway 24 a few miles outside of Jacksonville. Many commercial enterprises on this strip are named after themes of patriotism or God. The A-1 Dry Cleaners is up the street from Divine Creations Salon and next to Freedom Furniture. Neatly pressed summer camouflage uniforms hang in a row in the window behind a sign that reads, “NAMETAPES MADE AND SEWN ON. 1 DAY SERVICE.” This spot used to be called ABC Dry Cleaners, and it was, along with Hadnot Point, a major source of TCE and PCE contamination to the base’s water supply.

Partain is a heavy-set man with a goatee and a predilection for aviator sunglasses. He wore shorts and a brown T-shirt that read “Surf City, USA.” The tourist look belied his mood. He pointed across the street to the base, where a chain-link fence and a row of loblolly pines separated the roadway from the base’s family-housing neighborhood called Tarawa Terrace. Next to the entrance gate, four bright-yellow pole-stubs surrounded a concrete square the size of a dinner plate. That is now-infamous TT26, a well that supplied Tarawa, where Partain’s family lived.

“This is the dry cleaner here, and it slopes toward the river, this way,” he said, pointing toward the well. “We are nine hundred feet from TT26. That was the well that was sucking in the plume and feeding the area. They let it pump for thirty years and they poisoned a lot of people. When I look at it and I first saw the monitoring wells, every time I see them I just get angry.” Some gulls flew overhead, heading away from the ocean.

“I lived on Hagaru Road until I was four months old. I looked normal and everything appeared normal at first,” said Partain, wiping some sweat from his face. “It’s every woman’s worst nightmare, that something they can do when they’re pregnant can affect their unborn child. I’ve seen it when I talk to the mothers and they learn their child was poisoned and affected. I saw it in my mother’s eyes, the most heartbreaking look, despair, that I’ve ever experienced in my life. To look in my own mother’s eyes and see the realization that while she was pregnant, she drank something that harmed her child. I was forty years old when I saw that look. Part of me wants to go on base and show my family, my youngest daughter. She keeps asking me, ‘Is what’s happening to you going to happen to me, Daddy?’

“I don’t want these things burning in my head, but I don’t want to stick my head in the sand either. I don’t want to forget about it. I have to understand it.”