• 13 •

ARE YOU DENSE?

THE AGING BREAST

Death in old age is inevitable, but death before old age is not.

—RICHARD DOLL

MOST OF THE TIME, BREAST CANCER IS A DISEASE OF grandmothers. At the time my grandmothers got sick, reproductive cancers were not openly discussed. My mother’s mother’s mastectomy was obvious, though, as a sort of chasm under her matronly dresses, and it loomed large in my childhood imagination. I never knew my father’s mother. He was only nine years old when she became ill in Richmond, Virginia. For many years, she would go in and out of the hospital for surgeries or radiation therapy until she died in 1961. To this day, my father loves morning time, because that’s when his mother was happiest and strongest, singing in the kitchen and working in the garden. He never gleaned what kind of cancer Florence really had, and it’s even possible she didn’t know. I’d always heard she died from sort of stomach cancer, and it was only recently that I’d learned it might have been ovarian cancer, which is genetically related to breast cancer. I pursued it with my dad. “The information I got was always filtered through protective layers,” he said, fifty years after the fact. “They tried to keep hidden the information that she had cancer. The doctor believed that no patient should ever be told they have cancer.” I asked my aunt. “Well, I believe she had some sort of intestinal cancer,” she said.

I sent away for my grandmother’s death certificate from the Virginia Division of Vital Records, hoping it would have clues. It did. Immediate cause of death (A): malnutrition. Due to (B): metastatic cancer. Due to (C): pseudomucinous carcinoma. I asked my doctor about this diagnosis, and she said, yes, most likely ovarian cancer.

Because of its genetic link to breast cancer, ovarian cancer is also of interest to breast cancer researchers. When breast cancer runs in families, ovarian cancer is often lurking as well. Together, they form a dismal couplet called inherited breast-ovarian cancer syndrome. I’d heard that my great-grandmother, Florence’s mother, had also died of cancer, but again, no one was sure what kind. My father had been told it was abdominal cancer, another likely euphemism. Off I wrote to the Will County, Illinois, Clerk’s Office, Division of Vital Statistics for her death certificate. I learned that Anne Higinbotham died in 1930 at the age of fifty-eight. “Principal cause of death: Cancer of Lung. Other contributory causes of importance: Cancer of Breast.”

Bummer. Two generations in a row of related cancers, only two generations removed from me. Plus a grandmother on my mother’s side. After I received the death certificates in the mail, I pretty much ran to see a genetic counselor. I knew the odds if I inherited a mutation in the BRCA genes: up to an 80 percent chance of developing breast cancer and a 45 percent chance of developing ovarian cancer. Shonee Lesh listened to my family history and made a chart full of circles and squares that resembled a geometric child’s puzzle.

“My job is to look for patterns,” she said. “On your mom’s side, there are cancers all over the place, but they don’t line up for major concern. It’s your grandmother and great-grandmother on your father’s side that are the concern. BRCA is the most probable explanation. It’s high enough for us to have this conversation and for you to be tested.”

My insurance company, however, disagreed. It would pay for testing if I had a first-degree relative with breast cancer (mother, sister), but not for grandparents, even two in a row. The BRCA genes are patented by one company in the United States, Myriad Genetics, and it has decided the test to decode the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes will cost its customers about three thousand dollars. It’s expensive enough to make insurance companies fairly ruthless about it.

BRCA genes are most commonly found in eastern European Jews, with about one in forty carrying the most common genetic errors (in the general population, the rate is about one person in five hundred). But my Higinbotham foremothers were not Jews. They might have carried other mutations in the BRCA genes, such as one known to have arisen in Iceland in the mid-sixteenth century. This mutation, called 999del5 BRCA2, developed because of a missing piece of DNA in a single individual who enjoyed some reproductive success. Or my grandmothers could have inherited one of the seven hundred other distinct cancer-causing variants found in the BRCA genes among Dutch, Germanic, French, Italian, British, Pakistani, or French-Canadian populations.

The BRCA genes are the most common and deadly of the genetic variants, but there are numerous others—some discovered, some not yet—my grandmothers could have inherited. In families with histories of breast and ovarian cancer, less than half of them have BRCA mutations. It’s also remotely possible that my foremothers, coincidentally, developed their own, unrelated, non-inherited mutations. In total, only about 10 percent of breast cancers are believed to stem from a heritable gene flaw.

The average lifetime risk of breast cancer in the United States is one out of eight, or 12.2 percent of women who reach the age of ninety. When Lesh plugged my risk factors into something called the Tyrer-Cuzick Risk Assessment Model, it calculated my risk at 19.8 percent. Lesh told me that when an individual’s risk reaches 20 percent, doctors recommend aggressive screening, such as annual or semiannual pelvic ultrasounds (for detecting ovarian cancer) and semiannual breast MRIs in addition to mammography. But absent BRCA testing, the results of which could push my magic risk number way up, I, like most women, would be more or less on my own.

IF CANCER IS A DISEASE OF AGING, THE OLDER WE GET, THE MORE vigilant we need to be. It seemed like a good idea to understand the risk factors. Age and family history may be the major ones, but as I was learning, they’re not alone. Other standard risk factors are early puberty, late menopause, obesity, older maternal age, a record of a previous breast abnormality, and race (white women have a slightly higher risk than African Americans and a considerably higher risk than Asians or Hispanics). But—and here’s the disconcerting part—most people who get breast cancer have few of these risk factors, other than the big buckets of age and race. A stunning majority of women with breast cancer—90 percent—have no known family history. Equally perplexing, most women with the risk factors, even a bunch of them, still never get breast cancer. In other words, the standard risk factors are fairly useless. We still don’t really know what causes breast cancer.

Obesity is a good example of how confusing things can get; it’s a risk factor for postmenopausal women, but oddly, a protective factor for younger ones. Other risk factors have been or are being considered for inclusion in risk models, and if you’ve read this far, you know some of them: radiation and chemical exposures, alcohol consumption, a high-fat diet, use of birth control pills, hormone replacement therapy, and nationality. Women in the United States and the Netherlands have the highest rates in the world. Japan has among the lowest. Scotland is middling. Interestingly, women in China get the disease, on average, ten years earlier than their counterparts in North America. Lately, a newish risk factor has emerged, and it’s not one often thought about: breast density. If you haven’t been clued in, you’re not alone. One fifty-year-old friend told me she’d recently returned from a mammogram. The radiologist told her she had very dense breasts.

“Thank you!” she burbled, thinking it a compliment. I had to explain to her that the doctor was not commenting on her firmness, which is, it must be said, admirable. I told her that density is a measure of the ratio of fat to glandular tissue. She looked decidedly dispirited. Not only that, I continued, but dense breasts make reading mammograms difficult, and women with dense breasts are at higher risk for breast cancer, a double whammy. Now she was glaring at me. I changed the topic. But I’ll say more here. Two-thirds of women go into menopause with dense breast tissue, and one-fourth retain it afterward. Women with the densest breasts are believed to have a four- to five-fold greater cancer risk than their peers, making density the biggest risk factor for cancer after age. It’s also the biggest risk factor you’ve never heard of: 90 percent of women do not know if they fall into this category.

IN A BETTER ATTEMPT TO KNOW MY BREASTS AND FORETELL their destiny, I hied my aging, American self down to Dallas. There, I met Dr. Ralph Wynn. He is the kind of man you’d want to be your radiologist, should you ever need one. A soft-spoken Texan, he’s kind, careful, and very experienced. He’s been reading murky mammograms for over twenty years, and has put in time at some of the best cancer centers in the world. He can find the proverbial needle in the haystack, seeing minute “disruptions” in impossibly hazy fields of white-and-gray X-rays and sound waves. Although Wynn has recently been named director of breast imaging at Columbia University Medical Center, I was lucky to catch him while he was still practicing at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and overseeing the country’s only commercially available 3-D breast ultrasound machine. I didn’t want to miss out.

It’s not easy to see inside breasts. If it were, mammograms wouldn’t miss 20 percent of all tumors. MRIs are better, but they require getting injected with a dye and spending thousands of dollars, not to mention enduring forty-five minutes of lying immobile in a tube the size of a small sewer main. They are the domain of highrisk women. Three-dimensional ultrasounds could be a decent compromise. They have been used in Sweden for years, but they are new to the United States and insurance will not pay for them yet. Wynn is participating in a national study to compare their effectiveness to mammography in a bid to get them more widely used. The general consensus is that ultrasound picks up more tumors than mammography, but it also picks up more lumps and shadows that are not cancers, the so-called false-positives that are the bane of women, insurance companies, and government task forces. Wynn wanted to know how many lives could be saved by this technology and at what cost. My interest, though, was how ultrasound can draw back the curtain on how my breasts are changing as they enter middle age.

For his study, Wynn enrolled several hundred women with dense breast tissue. He said he’d be happy to examine me as a test case. He asked me to send him two sets of mammograms—my oldest and most recent films—before arriving.

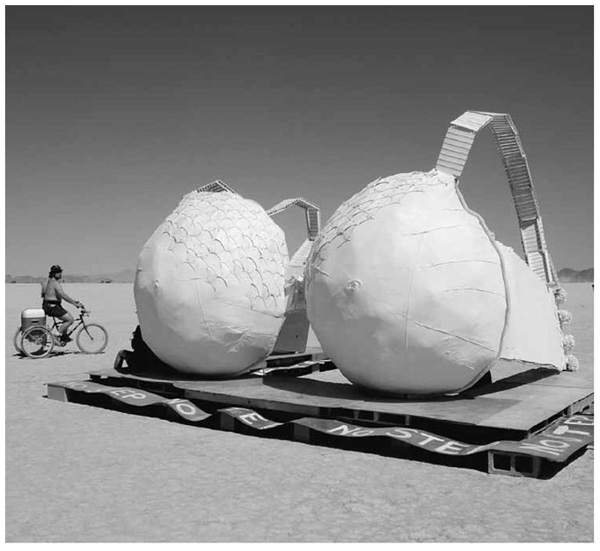

On the appointed spring day, Wynn met me in the lobby of the modern Seay Building on the sprawling University of Texas campus north of downtown. We walked past the immense lobby sculpture of shiny orange globules stretching to the high ceiling. “I think it looks like sperm,” said Wynn. I was thinking the same thing. He introduced me to Robin Eastland, the technician who would operate the 3-D machine, called the Somo.v. A cheerful Texan in her mid-thirties, Eastland led me to an exam room on the third floor and handed me a gown, which was, naturally, pink. When I was settled in, she told me that unlike mammography, this machine would not squeeze my breasts in a vise grip. The worst part of the procedure would be the cold gel.

I lay down on an exam table, and Eastland parted aside my gown. She held a tube of sonography gel over my right breast.

“Ready?” she asked.

I nodded, and the tube belched out a cold substance resembling Elmer’s glue. Eastland smeared it around. Then she maneuvered a book-sized square attached to a mechanical arm above my breast. The bottom of the square held a disposable chiffon-like screen that compressed and conformed to the outer half of my breast. She pressed a button, and an automatic transducer on the other side of the screen moved down my breast like the rollers on a massage chair. The machine sent high-frequency sound waves into my tissue, recording the time it took them to bounce back. (Sonography is also used to help boats find deep-sea fish and to measure fetuses in the womb.) In my breasts, when the waves encountered a change in tissue density, such as from a cyst or rib, the signal hesitated, and the object’s size and location got marked as a dark color on a computerized 3-D map. The whole breast map took several minutes.

When we finished, we found Wynn in his reading station, which reminded me of the scene in The Matrix where Keanu Reeves meets the sentient machines. Six large screens surrounded a couple of office chairs in a small dark room, each flashing pictures of images from mammograms and ultrasounds. “I spend most of my time alone, sitting in the dark,” explained Wynn, who has close-cropped hair and round wire glasses. Now that he said it, I saw that he was a little pale. I wanted him to drink an Arnold Palmer and go play golf in the sun like normal doctors, but first I wanted to see my pictures.

One neat thing about digital 3-D ultrasound is that the CAD software can produce both coronal slices—like individual cuts of deli ham—or the whole ham hock from any angle you want. If you go for the slices, each one offers a view about two millimeters thick. Since the average tumor is twice that size, it will probably show up. The images aren’t as crisp as a mammogram, but the contrast is better. On a mammogram, breast tissue looks like a big uneven clump of snow, while a tumor might look like a cotton ball. On an ultrasound image, a tumor looks like a very dark patch on a bed of somewhat lighter patchiness. Wynn’s job description, then, falls somewhere between reading tea leaves and looking for eagles flying across a night sky.

First Wynn pulled up the rotating 3-D image of my breast, slightly flattened by the rollers and appearing taller than it was wide.

“It looks like a fat piece of French toast,” I said.

“Or croque monsieur,” he countered.

“Panini.”

“Grilled cheese.”

We’d now established we were hungry. To get through all the slices for both of my breasts meant reading about five hundred images. Wynn flew through these with his mouse wheel, moving from the nipple to the chest wall. He could have been Captain Kirk piloting at high speed through a remote, hazard-filled galaxy. “Your breast tissue looks nice and homogeneous,” he said. I’m relieved. But then he slowed down through some honeycomb patterns and told me my tissue is fibrocystic, especially toward the outer edges. This can be a risk factor for disease. He kept scrolling. “Here we can see ductal structures radiating from the nipple.” They looked like fuzzy spider veins of varying thickness, indicating that some contained cellular fluid.

Not all of my milk ducts were visible. Some, explained Wynn, had regressed with disuse. That notion made me feel like an expired dairy product. It had only been five years since I last lactated, but already my glandular cells were being replaced by fat cells. (If I get pregnant now, in my early forties, this process would quickly reverse.) This surprised me; I knew breasts grew less dense after menopause, but I didn’t realize this process would be so evident so soon. Wynn pointed to the light parts of screen. “All of this here and here and here and here and here and here is fat,” he said.

To better show me the changes in my breasts over time, he uploaded on the opposite computers the CD my doctor had sent of my previous mammograms. First he pulled up an image from my last mammogram, taken six months earlier. Here the colors were reversed; glands are white, fat is dark. “The more white, the more dense,” he explained, pointing to a portion of the image. “The fat content in here makes up at least 75 percent of this whole area. It may look denser to the untrained eye because of superimposed parenchyma.” (A quick refresher from chapter 3: the breast is made of three major things: fat, gland, and stroma. The gland is sometimes called ductal, parenchymal, or epithelial tissue. The stroma is the extracellular universe surrounding the gland and supporting it. It includes collagen, growth factors, and proteins and also looks whitish on a mammogram.)

Because of my family history, I got my first baseline mammogram when I was just thirty-three, and got another after I turned forty and was finished with pregnancy and breast-feeding. The point of a baseline is to have something for radiologists to compare with later images. Wynn pulled up my first mammogram. It’s from an older machine, and fuzzier. “You can see there was fat then but there was a lot more white,” he said, pointing to the screen. “And so you’re progressively depositing more fat as the fibroglandular and ductal system atrophies. It’s a good thing you don’t have denser breasts now. For your age, you have tissue that’s appropriately regressing and you have progressively more fatty breast tissue.” In the early film, my ratio of fat to gland was about 40-60 whereas the ratio ten years later was the reverse. The verdict: moderately dense tissue, not high risk.

I don’t love it when people start sentences with “for your age.” But with breasts, the march of time is inexorable. Most women’s breasts are like mine, losing dense tissue as their reproductive years wane. Breasts are considered “very dense” if the gland and stroma remain, taking up 75 percent or more of the breast. No one is sure why some breasts are denser than others, but it tends to be hereditary. There’s a big search on to identify these genes in the hopes of someday linking them to cancer and targeting them with drugs.

Women tend to have denser breasts if they’ve never had children. Hormones also influence density. Menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy develop denser breasts almost immediately. If they take tamoxifen (an anti-estrogen drug used in cancer treatment), the mammary gland retreats and gets replaced by fat. Not everyone should start popping tamoxifen, but it proves that drugs can change your breasts, and fast. Some studies show that wine drinkers have denser breasts, as do smokers and women eating high-fat diets. These things may turn on or off genes in ways that promote inflammation, growth, or instability in glandular cells.

In this way, density stands in for breast cancer risk overall. If a woman is postmenopausal, she can reduce her risk by eating well and exercising and by not drinking excessive alcohol or smoking. Unfortunately, though, these gains are small. It appears that by the time a woman reaches menopause, her cancer destiny is mostly laid out by some mysterious combination of her genes, the pattern of growth taken by her breasts, and the accumulated damage (or lack thereof) to her cells over many decades. Menopause is simply the end zone in a long game of chicken between breasts and carcinogens. By this stage of life, it’s too late for a woman to change the things that may have set her down a particular path: the childhood exposures, her reproductive history, the hardiness of her genes. New exposures, such as to hormone therapy, may put her over the edge. But her cells will keep aging no matter what she does, and as they do, they’ll collect more mutations. Most women take hormones without a hitch. The risk—a doubling in deaths from breast cancer—sounds bad, but it is the equivalent of about two additional breast cancers per year for every ten thousand women taking hormones. It’s enough of an effect, though, that when a third of hormone users quit following the study results of 2003, the U.S. breast cancer rate noticeably declined.

I was increasingly learning that the whole blame-your-lifestyle approach to understanding breast cancer is problematic. In a way, it presents an excuse not to probe into the deeper reasons for disease. As environmental historian Nancy Langston put it, “Traditional medicine and public health practices have been reductive, focused on individual risk factors for disease.” Instead, she argues, we need a more ecological understanding that explores how genes and the environment interact to compromise our immune system in the first place. Ultimately, we should be asking and answering, Why do some women have dense breasts? Is there anything we can do to prevent or lessen the impact once it kicks in?

In lieu of that understanding safeguarding our breasts any time soon, I figure knowing our tissue density can at least help us make more informed decisions about the choices we have left in middle age, but with the knowledge that those choices are imperfect. Women with very dense breasts might want to avoid taking additional hormones if the benefits aren’t worth it for them. They might want to lobby their insurance companies so they can get screened more often, using a greater variety of technologies like the 3-D machine to boost their odds of catching problems. Mammograms might work pretty well for most older women, who tend to have low-density breasts and slow-growing tumors. Even in this group, however, the benefits of early detection are debatable, because it’s likely that many of these tumors would not be lethal. The statistics get more depressing on the effectiveness of mammograms for women between the ages of forty and fifty, who often have more aggressive, fast-growing tumors that are harder to spot. Recall the enormous flare-up in 2009, when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reviewed the data and recommended against the decades-old policy of women under fifty getting routine mammograms (later, the panel backpedaled to say screening decisions should be made by patients and their doctors).

Here’s the sorry and under-sung fact: mammograms for my age group are lousy. Thanks to time spent in Wynn’s flight deck, I now know why: we still have too much white stuff (the dense glands) that X-rays can’t see through. A 20 percent failure rate is just not good enough. But what especially rankled the task force were the costly false-positives. Better to do none at all, it implied, until your breasts fatten up. That recommendation wasn’t the only blow the task force dealt. There was another that drew far less attention: women should no longer be taught how to perform breast self-examination, known as BSE. Equally disheartening, the task force went on to say there wasn’t even enough evidence to recommend clinical breast examination, the kind performed by your doctor during an annual checkup.

Like many women, I wasn’t liking the options left by the task force. We’ve all heard that early detection can be the key to surviving this disease, at least for some if not all tumors. But how, in women under fifty, is a growing tumor supposed to be detected without mammography or people looking for it? Where I live in Colorado, fully one-third of all breast cancers occur in women under fifty. Put together, these two recommendations meant that we might as well just take up voodoo and buy a Magic 8 ball.

As blogger Leigh Hurst put it, “Wow—are you kidding me? How can this be? A BSE is what saved my life.” Hurst found her tumor when she was thirty-three and has gone on to promote breast self-awareness through a hip website called Feel Your Boobies. It’s a well-recognized fact that most breast cancers are found by women themselves, not by mammograms. Often, this happens by accident, not during a formal search-and-destroy mission.

I learned that the task force’s BSE guidelines were based on two large studies, one in China and one in Russia. Those studies compared women who were taught how to do BSEs and did them, with women who did nothing, and found discouragingly similar death rates from breast cancer. At the same time, the women who performed BSEs found more false lumps.

But a number of other experts have criticized those two studies as flawed, saying, for example, that the women in China received inadequate training and that the Russian study ran out of money for follow-up. Other studies modestly support BSE, including one in Canada, which did find a lower death rate in women who were well trained. A recent study from Duke University found that mammograms, MRIs, and BSEs were equally effective in finding tumors in high-risk women. For women at highest risk of breast cancer, mammography may actually be hazardous, since faulty BRCA genes make breast cells more sensitive to the damage caused by radiation used in the procedure. For these women, BSE might actually be their best option.

The strongest argument against BSE is that it’s difficult to do properly and requires training. For a large population, it’s simply unrealistic, according to Dr. Russell Harris, who served on the U.S. task force and supports the recommendation. But for a motivated individual, BSE could be your best friend. As Lee Wilke, a breast surgeon and the author of the Duke study, told me, “BSE turns out to be only as good as the person doing it.”

I SUDDENLY WANTED TO BE VERY GOOD AT IT. THERE WOULD BE no more half-assed shower gropings. I was going to learn to do it properly. I bought a fake, silicone boob (forty-eight dollars from Amazon.com) and considered where best to stick it on my chest. It wasn’t just any fake boob; this one came with lumps and bumps designed to mimic the nodularity of real breasts. It also came embedded with a number of “tumors,” or harder bits of plastic of various sizes and at various depths. It felt almost disturbingly real, with a squishy nipple and smooth skin. Manufactured by a company called MammaCare, this model was designed to teach women how to perform “tactually accurate” BSEs.

Per the instructions, I lay down and placed the cool falsie below my collarbone, which made me feel like a multi-teated mammal. I popped the accompanying DVD into my laptop, which I perched on my stomach, and prepared to enter the world of low-tech, lastresort cancer detection.

MammaCare is considered the Harvard of BSE trainers. Its squishy silicone booblets are used in the Mayo Clinic and in medical schools throughout the country. Company cofounder Dr. Mark Goldstein told me they were designed in a university lab after almost laughably painstaking research into “pressure load curves of the human breast.” Goldstein is considered a sensory scientist, a man who believes that we can train and use our senses to work like finely calibrated machines. He told me his father ran a metal fabrication company and could judge the correct width of sheet metal within a hundredth of an inch, using his fingertips. One night this man happened to detect a three-millimeter tumor in the breast of his wife (Goldstein’s mother). Most tumors are ten times that size by the time a woman or her partner finds them. Goldstein wanted to create a training program that was simple, thorough, and effective, and that ordinary women could use. He said BSE, performed right, is as accurate as mammography, especially in women under fifty.

“We can take someone who can’t find a marble on a table and teach them to detect a three-millimeter tumor inside a breast,” he said.

I was ready. I pressed play. A no-nonsense woman with an early-1990s hairstyle introduced the concept of the “vertical strip” search pattern. Goldstein calls this “mowing the lawn.” The circles of yesteryear are clearly no longer in favor. Following along with the video, I proceeded to feel up my model along these lines, using the fat pads on my three middle fingers to create a small dime-sized zone. I dutifully applied three pressure depths—surface, medium, and deep—at each spot on the grid. I immediately detected two small, hard “tumors” on the left side and one on the right. During the review a few minutes later, though, I found out that I missed two others, including a big one deep under the nipple. To feel those, I had to press down much more firmly. If my model had been a water balloon, I’d have popped it. I was unsure whether I’d have the guts to press that hard on the real deal, and I was right.

When it was time to trade the model for my own breasts, I could tell right away that things are much more complicated in flesh and blood. If the model represented the geography of rolling tundra, my body felt more like the great Himalayan upthrust, complete with granite, lakes, ice, snow, and the occasional civil war. It was harder to tell what was going on or where a cancer might lurk. And it was harder (and painful) to push down very far through all my natural ropy tissue. If I were to develop cancer, I’d have to hope for shallow tumors. Also, I have to admit, it’s frightening as hell. What are all these bumps? And the exam takes some time, about seven glacial minutes per breast when you’re starting out. Discouraged, I called Goldstein to ask for tips. He told me that the more I practice BSE, the better I’ll get at telling what’s normal and what isn’t, especially if I do the exam at the same time every month, ideally at the beginning of my cycle before the late-month progesterone-hit makes things even knottier in there. “The fingers remember,” he reassured me. “They operate brilliantly, but they need to be used. You can’t sit down at the piano and start playing Mozart.” He also reminded me that having my breasts squished between mammography glass hurts even more. Good point.

I believe Goldstein; I believe that it’s possible and important to learn to do this well. I would like to think I will do BSEs, if not every month, then at least a few times between mammograms. But I also have to acknowledge I was never great at practicing piano, and I recognize I might not be destined for BSE virtuosity. I called William Goodson, a San Francisco–based breast cancer surgeon and researcher and another proponent of BSE. He told me that just getting to know one’s own breast geography is a major accomplishment. For women who can’t bring themselves to conduct the full-on regular BSE, just better breast awareness is a big step. No one knows your breasts like you do. “It’s useful to have a woman become familiar with her breasts, to be aware of any changes. You’ve got to sit down and look at them. And don’t only look for lumps. Many cancers feel like a more irregular area, where the skin doesn’t move right or feel quite right.”

This much, I hope, I can handle. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that cancer detection is as much art as science. BSE isn’t perfect, and it’s not going to work for everyone. But my foray into self-monitoring has convinced me that I can undertake some useful reconnaissance. As cancer survivor Hurst put it, “We’re lucky our breasts are on the outside of our bodies where it’s possible to become familiar with how they feel. We’re not talking about our lungs here.”

My best advice to you, dear reader: know thy breasts.