A NEW PATENT OFFICE AND PATENT STATUTE

In 1835, Henry L. Ellsworth was appointed the new patent office superintendent. He would be a godsend for inventors. For most of his life, Ellsworth knew little about patents. But he did understand complex legal matters. More important, he understood inventors. His father, Oliver Ellsworth, was the Chief Justice. His twin brother, William, was the governor of Connecticut and a classmate of Samuel Morse.

Ellsworth too sought a life of public service, but one with more adventure than either his brother or his father. Before applying for the post of patent office superintendent, Ellsworth’s commission took him to the Indian tribes on the American frontier, where his travelling companion was Washington Irving.

What brought Ellsworth to the world of patents undoubtedly had something to do with Ellsworth’s close friend and fellow Hartford denizen, Christopher Colt, father of Sam Colt. Ellsworth was soon to become a godfather figure to Colt and likely did more to bring about Colt’s success than any other. As fate would have it, Ellsworth applied for the superintendent position in mid-1835, just as Colt was preparing to patent his revolver.

Ellsworth took his post on July 8, 1835, and he began making drastic changes without delay. Although most Americans understood the failure of their patent system, Ellsworth was one who was determined to do something about it. Housecleaning was his first order of business. Organizationally, the patent office was in shambles. Ellsworth spent his first month creating patent files and having them indexed. Then he took the sixty models that were cluttering his office and put them in storage. He also created a comprehensive list of every patent application and made up new patent office letterhead.

It was amidst this chaos, on July 24, 1835, that Colt paid Ellsworth a visit, seeking advice on how to patent his revolver. The past four years had been ugly, utterly humiliating years for Colt. After returning from his laughing gas tour he worked with almost a dozen gunsmiths to complete the design. Then came the rugged life on the road, peddling his guns to any army major who would show an interest. At six feet, Colt was tall, outgoing, and a lively bachelor, and the nomadic life fit him well. Yet he desperately needed another way to raise more money. So Colt decided to put his faith in the patent system. If he could secure his patent, he hoped investors would come flocking in.

The advice Colt received from Ellsworth wasn’t what he expected. Ellsworth told Colt to hold off applying for his U.S. patent—critical as that would be in protecting the potential fortune Colt stood to make with his revolver. Because of international patent laws, Ellsworth advised Colt to secure his patents in Europe before filing in the U.S. At the time, a prior U.S. filing would bar Colt from obtaining a patent in Great Britain. Only a month later, on August 24, 1835, Colt set sail for England, and then to France.

Although Colt successfully obtained his international patents, he returned heavily in debt. The costs for European patents were staggering: $676.50 in England and $341 for France, money he most likely borrowed from his father. While the $30 fee in the U.S. was substantial, enough to build up a surplus of around $150,000 in the patent office coffers, it was miniscule in comparison to what applicants paid in Europe.

Foreign patents in hand, Colt turned his attention to the U.S., where Ellsworth quickly shepherded Colt’s application through the patent office. It issued on February 25, 1836, without any examination for novelty. But Colt now had what he needed to continue his dream, for a patent would give him the credibility to raise desperately needed capital. Colt’s immediate plan was to raise funds to build a manufacturing factory in New Jersey. He first turned to his father for a short term loan. Colt’s father was reluctant to advance any more money, preferring that Colt find other investors. Then Colt sought the help of his cousin Dudley Selden to help negotiate a loan, still hoping his father would join the effort and help provide some financial backing. Hearing of his son’s plans, Christopher Colt advised him to use Henry Ellsworth to provide letters of recommendation to the Army and Navy Departments. They, not him, should be the ones paying for the revolver’s manufacture. Still, Colt continued borrowing from friends and relatives and raised enough money to charter the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company of Paterson, New Jersey, on March 5, 1836. He produced his first revolving rifle at the end of 1836, then began working on pistols. The following year he would produce nearly 1,000 arms.

But sales were almost nonexistent. So Colt, now following his father’s advice, went back to Ellsworth for letters of recommendation. Although Ellsworth did provide the recommendations, Ellsworth had little time to be of any more assistance. Ellsworth understood the deficiencies with America’s patent system and was determined to do something about it. His attention had turned from mundane organizational issues to the real problems facing America’s patent system, including the lack of substantive examination of patents.

What Ellsworth accomplished in a single year was, and still remains, unprecedented. With Ellsworth at the helm, 1836 proved to be the most monumental year in patent office history. Ellsworth had a plan to make life better for every inventor, not just Colt.

The superficial logistical matters he quickly set in order—the general state of disarray of the patent office, the garaged models, the backlog of patents awaiting the President’s signature, and missing patent numbers. But the real problem Ellsworth quickly learned was that America’s patent laws didn’t protect inventors—and they weren’t going to protect Colt.

The ideas behind how to change the patent system came from an unlikely source: the patent office machinist, Charles Michael Keller. As an adolescent, Keller spent most of his time hanging out at the patent office with his father, who was then the patent office machinist. By the time Keller’s father passed away, Keller was twenty-one and had already logged eight years at the patent office. It was natural for Keller to be appointed to take his father’s stead as the patent office machinist, presumably to work with the patent models.

When Ellsworth took his position as head of the patent office, Keller was twenty-five and had four more years of patent office experience under his belt, some as a patent clerk. It was a lowly position—one that paid less than half of what other government clerks received. But Keller knew the patent system and Ellsworth was smart enough to listen to him. Keller put together a list of changes that he felt necessary to fix the patent office. Ellsworth summarized these in a letter to Congress. Foremost on the list was the need to actually examine applications to make sure the ideas they contained were new. Keller had seen the abuses where unscrupulous individuals would visit the patent office, study a particular model, then fraudulently claim the idea as their own in a newly filed patent application. These fraudsters would then fabricate evidence to show they’d invented the idea first. This wasn’t a new phenomenon. This had been going on ever since the days of Whitney. It was quite a cottage industry. With the certified patent in hand, signed by the President, the copier would seek royalties from legitimate businesses. It has been estimated that this business took in a half million dollars per year.

To ensure that patents would be properly examined, Ellsworth proposed to hire patent clerks with scientific backgrounds, to pay them a decent salary, and to provide them with a library of scientific journals so that they could examine applications in view of what was already known. Keeping the model requirement intact was also key to creating a successful patent system. Finally, Ellsworth wanted to publish issued patents and use them to generate a library of patents that would serve as a knowledge base for examining future patents. Other ideas included eliminating the need for the president’s signature, a step necessary to eliminate the three months it usually took to do this, and allowing foreigners to patent in the U.S. but only if they paid the same amount that their home countries charged—$600 in England and $200 in France and Austria.

Ellsworth’s most pressing need was for a new patent office. He fretted over the inability to display the models and that the patent office, like so many other federal buildings, would catch fire. With a surplus of $150,000, Ellsworth thought it was time to put this money to good use. America was the only country with a model requirement and these scientific models should be prominently displayed in a grand American museum.

While Ellsworth was working with Keller on ideas for overhauling the patent system, Maine’s newest senator, John Ruggles, arrived in Washington with a keen interest in the patent office. Ruggles was not only a lawyer and a judge, but also a passionate inventor with a new idea for a cog railroad. And he was adamant that his idea be protected. After arriving in Washington, the first thing Ruggles did was to visit the patent office. Upon discovering the tattered state of affairs, Ruggles was as shocked as was Ellsworth just a few months before.

Together, the two men discussed what could be done and Ellsworth’s plans for reform. When Ruggles discovered the genius behind Ellsworth’s suggested changes, he asked to meet the clerk. The two, statesman and patent office machinist, soon gained a mutual respect, and together hammered out a new patent statute. The document marked the end of Jefferson’s forty-three-year experiment, one in which Jefferson, frustrated with a myriad of issues involved in running a patent system, quietly bowed out. Now, after forty years of trial and error, rife with fraud, it was time to start anew. Ironically, what emerged was a patent bill not too dissimilar from the original Patent Act of 1790. Once again, patent applications would be examined for novelty, just as Keller—and Jefferson in 1813—had recommended. But this time, it wouldn’t be by the Secretary of State. It would be by trained patent examiners. The new bill also provided $1,500 to purchase a library of scientific books to aid examiners, and it paid the patent office clerks a competitive salary. It eliminated the need for the President’s signature and allowed foreigners to patent—as long as they paid the outrageous fees charged by their own countries. Applicants were still required to supply a model, which was to be publicly displayed. And for this to happen, the new bill asked for the existing $150,000 surplus to be used to construct a new patent office—a fireproof home to show off the nation’s patent models. In what would prove to be an ill-advised decision, the act also allowed patent holders to apply for patent term extensions. If fourteen years wasn’t enough, the patent holder could ask to extend his monopoly another seven years.

The statute crafted by Ruggles and Keller was signed into law on July 4, 1836, ten years after the passing of Jefferson and Adams, and sixty years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The signing date wasn’t coincidental. Many considered this document to be America’s second Declaration, not one to declare political independence from Britain, but to emphatically state America economic independence. With it, America gained a monumental advantage over Europe, not only in promoting innovation, but also in supporting America’s groundswell of innovative energy. The Patent Act of 1836 would provide the framework to let inventors invent and investors to invest in their technology. It gave everyone the monetary incentive needed to put America’s creative energy to work.

And it was only fitting to have the second Declaration crafted by a young, innovative patent clerk who, working on the front lines, saw exactly what America needed. He’d seen the anxious inventors, toting their treasures into Blodgett’s Hotel. He understood their fears in putting their precious inventions into the hands of a bureaucratic system. And most important, Keller knew what drove them to invent. And with this understanding, Keller knew what it took to guide them along. In a sense, Keller’s contribution to protecting innovation was similar to what Jefferson did in protecting freedom. Appropriately, Keller was the man to discover and draft America’s second Declaration. To their credit, Ellsworth and Ruggles were smart enough to follow his lead.

After passage of the Patent Act of 1836, Ellsworth’s title changed. He was now the first Commissioner of Patents. Not counting Jefferson, Keller was promoted to become America’s first official patent examiner. His job was to compare the ideas found in patent applications with what was already known, in public use or on sale without the applicant’s consent. In other words, the invention had to be new. The self-educated Keller took on this task, single-handedly examining every application in every field of technology. It was no small task. His first challenge was to whittle down the backlog of nearly 100 unexamined applications. By November, he would need to examine another 308 that had been filed under the new law. Over time, more examiners were hired, and in May 1845 Keller decided to study law and left the patent office—but not patent law. Keller became a successful patent lawyer in Washington, then moved his practice to New York.

With the new patent act in place, Ellsworth’s organization skills were again put to good use. He began a new numbering system, with Ruggles’ railway patent being assigned patent number one. Then he turned his attention to constructing the new patent office.

It was to be built on the block bordered by F and G Streets and Seventh and Ninth. Originally, this plot was reserved by city planners for a national church or pantheon. After the Rotunda took shape, this plan was abandoned. Yet a famous building would soon rest on the forgotten site, and it would become one of the nation’s most visited. In only a few decades, the new patent office and model museum would receive more than 100,000 visitors a year who would see, as Abraham Lincoln put it, the real fuel of America’s economy.

Everything now seemed in place for innovation in America to thrive. It had a new patent statute and a new patent office under construction. America’s inventors were set—able to get good patents, then secure the investments they needed to bring their ideas to market.

But before that could all happen, the patent office would need to burn nearly to the ground, an omen signaling that America’s patent system was ready to begin anew. On December 13, 1836, one of the post office clerks woke to suffocating smoke. The clerk rushed to wake the night watchman, and a quick examination of the building showed smoke billowing out of the southeast end. Still in his night clothes, the clerk frantically scampered down the street, raising the alarm. The ruckus awoke the neighbors, who rushed to assist. Both Ellsworth and Ruggles were eventually notified and rapidly made their way to the flaming hotel. Ellsworth first tried the front door, but found it blocked. He then tried another entrance but the smoke was so thick he was unable to enter. Meanwhile, Ruggles went next door to the fire house with a crew of volunteers to lug out an engine. But when he went to pump water, Ruggles discovered that the leather hose had disintegrated. Not a drop of water made it to the fire. In desperation Ruggles started a bucket brigade, but the laboring men stood no chance. By the time another fire engine arrived, flames were shooting out the windows. It was all over.

Only twenty-two years before, William Thornton had successfully fended off British soldiers from burning Blodgett’s hotel to the ground, saving its precious models. Now, while the blueprints from a new fireproof patent office were still being drawn, these sacred relics were going up in smoke. The patents, the models, the drawings, the temporary home of Congress—all gone. In total, 10,000 patents were destroyed.

Ruggles immediately went to work to restore the documents, drafting a bill that requested patent holders to return their original patents so that clerks could make a certified copy. To motivate the inventors, any burned patent was declared invalid until a replacement copy was made by the patent office. Only 2,845 would eventually be restored.

And the new home for the patent office? Initially, it was moved into Ellsworth’s home on C Street. It would take four more years for the new stone building to be completed.

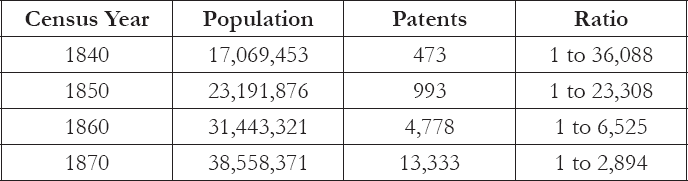

However painful, death by fire turned out to be a blessing. It served to accelerate construction of the new patent office and to give inventors a fresh zeal toward the new patent laws. Although filings initially declined, after the 1836 Patent Act was firmly in place and the new patent office was completed, patents began to issue in record numbers. The reaction to the 1836 Patent Act can be shown by the following table:

Decade |

Number of Patents |

1837-1846 |

5,019 |

1847-1856 |

12,572 |

1857-1866 |

60,094 |

1867-1876 |

130,240 |

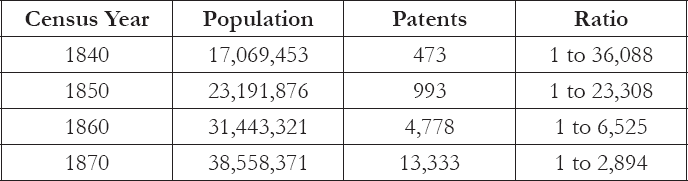

The number of issued patents can be compared to the population to determine the real rate of invention during the mid-nineteenth century, as follows:

Put another way, the rate of innovation as determined from the number of patents increased six times from 1840 to 1850, nine times from 1850 to 1860, and 13 times from 1860 to 1870, as compared to the increase in population.

Why did this happen? It can only be attributed to the new patent system.

For the next two decades, consider the patents that issued: the revolver, the sewing machine, the reaper, vulcanized rubber, and the telegraph, to name just a few. With a flood of active patents, though, litigation was sure to follow. The ensuing patent battles would attract the best legal and political talent of our nation’s history,—a sure sign that the protection of technology was critical to America’s success.