Russia, February 11, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Oh dear, how my bones are aching. Yesterday we moved twenty-five kilometers closer to the front. Now we are situated five kilometers behind the main fighting line in a burned-out village. No chicken, no cow, just here and there a house still standing. This place is the springboard back into the trenches.

Oh yes, and I was on horseback those twenty-five kilometers, on five different nags! I feel like a seasoned rider now, one who knows all the tricks of the trade. The mud makes walking a torture. First you sink in up to your shins, and then you can’t get out again.

And so I, crafty old fox, organized a horse. Without saddle, naturally, just with a pair of narrow cords running somehow past the ears as reins. Of course, I don’t know the first thing about horses or riding, and it wasn’t until after the first three kilometers that I realized I was riding a pregnant mare who bucked and wouldn’t run.

Whereupon, without much ado, I went into a barn in the next village and took a different horse, and that one ran. That beast galloped, stood on its hind legs, and never went in the direction I wanted. But I stayed on him for about ten kilometers, until I spied another that I took to be quieter and more docile.

I changed horses once again and, what do you know, it walked quite peacefully behind the wagons, until an expert told me that it was a young horse, about two months old, and would collapse any moment. So I looked for the next horse and discovered shortly after mounting that it was limping. I finally arrived here with an old horse that had a runny nose, and after a few words of thanks, I took my leave of him with a slap on the rump.

Twice in the course of the day I was thrown, to the general amusement of all. I was rather amazed myself at the way I accomplished the separate stages of riding, from the slowest snail tempo to a full gallop.

All in all, it was a delightful experience: by the light of the moon, with a rifle on my back, just like an old cowboy riding over the endless fields. My thighs are pretty sore today though. When I have to walk, it’s with a sort of swagger. But I really slept well. In a few hours we are going up front to a bunker in the open fields. Then we’ll look like pigs again. But the front is quiet for the time being. I hope the mail gets through. I’ll write you again when circumstances permit. Till then, kisses and greetings to Pop,

Your Boy

On my twentieth birthday, I wrote the following:

Russia, February 14, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Please don’t be frightened when you see my writing. On a gear of a cable drum I ripped a hole about a centimeter deep in my right hand, just underneath the index finger. So I’m pretty clumsy, but otherwise I’m fine.

I was supposed to go up front with the company as radioman, but I couldn’t be transferred because of the injury. Maybe it is fate or my luck. The front continues very quiet here. Hardly a shot all day long. Those of us on the staff are headquartered in the last houses of the village. Here in Panchevo there is neither chicken nor cow. [Author’s note: Sometimes, against the regulations, I smuggled in the name of a town in the middle of a letter, in order to let my parents know where I was.] They were all eaten up by our predecessors. We are getting mail in masses now, every day a sack, but all old letters posted around Christmas or earlier. Writing is pretty difficult because the hole hurts quite a bit when I move my hand. Many loving greetings,

Your Son

Russia, February 18, 1944

Dear Mutti,

I’m not in the position of writing you such a positive letter today as the last ones have been. You mustn’t take what I write too tragically, since I’m considerably better off than most. Overnight it has become winter here again; that is, the true Russian winter. The temperature is running between ten and twenty-five below zero. You can barely move against the icy east storm. The ice needles tear your skin to pieces. You can see only three meters ahead.

Yesterday, in this weather, we marched for thirty kilometers. Left at 5 a.m. and reached our destination at about 11:30 p.m. Quite a few collapsed along the way and will be listed as missing. Probably somewhere in these unending fields they have frozen to death. One never knows. A few vehicles also disappeared. All that was left of us arrived here, more or less frozen.

“Here” is a kolchos. That is to say an enormous barn without windows or doors. Or rather, there are holes in the walls without wood or glass. Inside the snow is just as high as outside, and the wind howls, too. Way at the back are two rooms with a door, and these can be heated. Our battalion headquarters staff has holed up there.

The rest of the company just kept going forward to the trenches to relieve another unit. Then the night passed. I’m sitting here now in the morning at the switchboard, listening to the awful early reports: in every company some dead, many frozen, some suspected of self-inflicted wounds. Some just got out of the trenches and took off on their own.

Everyone else spent the whole night shoveling just to see the sky, since these two-man holes can fill up with snow in a matter of minutes. There’s been nothing to eat since yesterday morning, not even coffee. And so, the poor guys are lying out there day and night, slowly freezing to death. I also threw up four times last night, have diarrhea, and sat up all night on the wet ground near the drafty door. In spite of that, I feel like a plutocrat. Enough for today. Kisses from

Your Georg

February 19, 1944

Dear Folks,

A few hasty shivering words. The east wind howls through all the cracks. Your ninth package arrived today, with quince jam, tea, and cookies. Everything is so much easier when you’ve had a sign from home. Russia is so gruesome.

Continually, eighteen-year-olds with frozen hands are being sent to the rear. Practically nothing is left of us now. But I’m healthy and all right compared to the others.

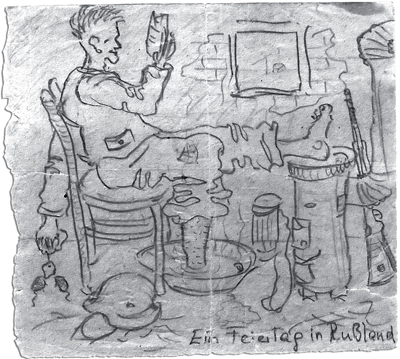

A holiday in Russia.

About June or July I can count on leave, if I’m not already back by then. Be well and don’t worry. Nothing will happen to me.

10,000 Bussis [Kisses], Your Son

February 21, 1944

Dear Mutti,

I’m still sitting here in my kolchos. We’ve been working day and night for the last few days, trying to get this place halfway stopped up. Now, if we heat all day, it gets nice and warm. We’ve also found some straw for sleeping. You can’t imagine how much that means, when outside the eternal east storm is blowing. At least one can warm a meal, toast some bread, and chase one’s hundred thousand lice.

A sign on our door reads, “Wireless Station, No Admittance,” but many half-frozen soldiers, passing by for one reason or another, beseech us to let them come in and warm up for a few minutes.

Once inside they sit around the little stove, quite silent and thoughtful, and revel in the great happiness of having warm hands and feet once again.

One thumbed through his notebook and suddenly said, “Did you know that today is Sunday?” Each one then described, almost as if speaking of something holy and long past, what he had done at this time of the week before the war. The others gazed silently into the fire. Perhaps some of them let visions of something beautiful from home pass in front of their eyes and were able thereby to forget for a few minutes their horrible current situation.

Sunday, for most soldiers, is the symbol of good times and relaxation. Maybe I think a little differently, since Sundays for us passed by almost just like all the other days. The big dates that many dream of, the bars, variety shows, and movies, weren’t so common for me. Maybe I had things so good that I never learned to appreciate the true value of Sundays? But it doesn’t matter.

When the soldiers leave after a half hour or forty-five minutes, they have new courage and the feeling of having experienced a few very special moments. Their eyes are glowing again, and thus they return back up front to the trenches.

It was your seventh package, not the ninth, that I received yesterday. Fantastic, and there’s hope of more mail. I sent you 159 marks today. Otherwise I’m doing fine, at least more or less. Many kisses,

Your Georg

P.S. The front is quiet.

Russia, February 26, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Quite late yesterday evening some mail arrived, including the letter you wrote on my birthday. I withdrew to a quiet corner and read. Afterward I noticed that my eyes were quite damp. Perhaps it was written with too much love for the disposition of a presently wild and degenerate fighter.

One becomes pretty hard in every respect here, and there are only a few things that really go all the way to the heart. A protecting wall absorbs most things before they get that far.

But when a mother writes from the distant homeland of her love for her son, and of the extremely favorable balance of the last twenty years, that goes all the way inside, even during the strongest bombardment. So, afterward one has wet eyes. It could happen to anyone.

Today the sun is shining beautifully; the snow is starting to thaw; the trenches are turning into mud holes again. The wind is blowing through the broken doors and windows. No wood, nothing to eat but “water soup,” one loaf of bread for four men, and unsalted sausage. So currently not very rosy, but I don’t think we will be here much longer. Kisses,

Your Son

March 2, 1944

Dear Papi,

Yesterday a few others from the staff and I went to a variety show in the village. The so-called Spotted Woodpeckers entertained us wonderfully for an hour and a half. It was a Viennese comedian, magician, and musical group from the army broadcasting station, Gustav, one that travels back and forth putting on shows for the soldiers.

It was very strange for me, here in the middle of cannons and uniforms, to see someone in civilian clothing on an improvised stage. They provided us with a wonderful change, and we certainly didn’t regret having trudged five kilometers in the morass to see it!

The Russians attack continuously to the north and south, but it is quiet where we are. In return for that, though, we are in serious danger of being hemmed in again. Very little is left to eat, and that little is no good. Give everyone my best greetings,

Your Georg

At noon on the fourth of March, Sergeant Konrad called me to the switchboard, where he had spent the last hour and a half busily connecting the incoming calls.

“You and Schmidt go immediately back to the repair unit and pick up two radio tubes of this number.” He handed me a scrap of paper with some scribbling on it.

“Where is the repair unit?” I asked.

“Exactly twenty kilometers southwest of here, there’s a good-sized town. That’s where the regimental mess and the bakery are located. The railroad passes through, so probably they have all sorts of other backup supplies, too. You can’t miss it.”

Taking just our rifles and bread bags, we started off. The day was warm and sunny. The track was torn up and softened knee-deep from the military vehicles, but we discovered firmer ground on the edges.

I found myself hopping to keep up with Baby Schmidt’s incredibly long stride. Schmidt hadn’t earned his nickname because of his age alone. His eyes were baby blue, and his soft pink cheeks still hadn’t felt the scrape of a razor. He reminded me of a giant’s baby from one of those fairy tales.

That day I asked him, “Why did they take you so young, anyway?”

“I joined up voluntarily,” Baby answered.

“Humph,” I grunted. “You must already be sorry about that decision.”

His face turned red, and he didn’t answer for quite a while. Then he said, “My father fell two years ago in Yugoslavia. Partisans. My stepmother took over our farm in the Black Forest. She and I never hit it off so well, and my brothers had all been drafted already. There wasn’t anything more for me at home, so I joined up.”

I thought about how different we all were. To me, volunteering to be sent to a front like this was the next closest thing to committing suicide. But I kept my thoughts to myself and concentrated on checking my compass as we tramped on.

We took our time, and by late afternoon we reached a small town where a tank unit was filling up on gas. We also tanked up with monster portions of a good beef stew from the field kitchen and slept that night on a soft bed of grain that filled up half a room in one of the houses.

By noon the following day we reached the place where the repair unit was supposed to be. It was a large village, filled with soldiers from the various supply units. The artillery was on the move, and everybody seemed to be in a hurry.

“It looks as though they are all pulling out,” Schmidt commented.

I stopped next to a soldier working under the hood of a heavy truck. “Can you tell me where to find the radio repair unit from Division 282?”

“Sorry, I can’t help you.”

We asked a few more times, but without success. Even at the command post no one seemed to know. As the day wore on, it became increasingly obvious that everyone was preparing for a hasty departure.

That night we made ourselves comfortable in one of the officers’ quarters that had just been vacated. Before turning in, I said to Baby Schmidt, “We might as well head back to the front tomorrow. The unit we’re looking for is probably long gone. There’s no sense in searching any longer.”

The following morning the streets were almost deserted. Most of the units had left the village during the night. As we passed the last houses, I stopped abruptly and listened.

“Do you hear what I hear?”

“Ja, heavy artillery and other firecrackers.”

“Yeah, that, too,” I said. “Nothing else?”

We both stood listening for a moment, then took off in the direction of one of the houses. After stopping once more to listen, we circled the house and there it was: a makeshift wooden box with three chickens and a rooster.

“Looks like someone prepared those for a trip but couldn’t fit them into the taxi,” Schmidt said with a broad smile.

After a futile search for an old woman, we were obliged to kill, pluck, and boil the chickens ourselves. It took us all morning, but while the last two were cooking, I also discovered two horses. We rode away at noon, minus the radio tubes but carrying mess kits stuffed with chicken pieces and two gas mask containers full of hot soup.

Heavy battle noises drifted from the direction in which we were riding. After only five kilometers we arrived at a rear position held by an array of antitank guns, entrenched soldiers with bazookas, and a few camouflaged tanks.

Just a few minutes later I saw a mass of fleeing soldiers running in our direction. “Let’s get out of here,” I yelled to Schmidt. We pulled up and galloped back to the village.

By two o’clock we could hear that the Russian attack had come to a halt. Asking around, we managed by evening to find the bloody remains of our unit sitting in a ditch next to the road. I served up the four chickens, saving the tenderest pieces, as usual, for Konrad’s ulcer.

A little later a bumpy cart rolled past, and there lay Haas, his face contorted in pain. When I grabbed his hand to shake it, he flashed a wide grin that belied his wound. “A thigh shot. I’ve made it. The war’s over for me.”

I stood waving goodbye as the horse pulled the cart away. I wondered if he really had been shot, or whether he had finally put to use what he had explained to me numerous times in all the technical details.

Just a few weeks earlier he had said, “And don’t forget, if worse comes to worst you can always shoot yourself in the leg. Do it through a loaf of bread or a folded jacket. That way you don’t have to worry about suspicious powder burns.”

However it had happened, Haas had received his injury, and he had more than earned his trip home. I hated to see him go, and I felt more forsaken than ever.

I shouldn’t have felt quite so forlorn, however. A few days later it became clear to me that Sergeant Konrad had received word of the impending tank attack over the wireless and had purposely sent us to the rear for radio tubes to a unit that didn’t even exist. He had wanted to save Baby Schmidt, who was too young to die, and make certain that I, his private cook, was also safe from harm!

Russia, March 17, 1944

Dear Papi,

You simply can’t describe some things because the reader wouldn’t be able to imagine them: the war here in this most forsaken of all countries; the Russians to the north, northwest, east, south, southeast; the river Bug seventy kilometers away, and us—a few sorry units where the staff is often larger than the number of fighting soldiers—continually struggling as much as possible to build a closed front.

Until two days ago the whole country was like soup where everything gets stuck and threatens to sink. By day we’re on the spot; that is to say, we build a front. During the night we wade fifteen to thirty kilometers in muck and goo toward the southwest. It takes us from six in the evening until 9 a.m., at least, just to gain a few kilometers.

Then there’s usually shortwave communication and shooting, and that’s why I’ve hardly slept a full hour for the last eight days. There’s only cold food, and not much of that. To drink? Ditto. The Russians are always close on our tails. The only hope is to get over the Bug as soon as possible, before Ivan really gives it to us.

If a vehicle gets stuck in the mud, it can’t be retrieved, because the Russians already have it. If somebody falls behind for one reason or other, Ivan has him. So we trudge, dead tired, hungry, with the feeling “If I collapse, Ivan’s got me.” The beards keep getting longer, the mood worse, and our strength less.

Since yesterday there has been an overwhelmingly strong snowstorm with temperatures under minus 20 centigrade. I’ve never experienced anything like it. This morning someone made a joke, and I wanted to laugh but was only able to produce a strange grimace. That made me very sad. I’ve always liked so much to laugh, and here I’m completely forgetting how.

Just now the Russians have broken into the left flank and are marching through with two battalions. The counterattack is in progress; the telephone lines are down, so I’ll have to get onto the wireless.

Since I’ve adopted the general point of view “What doesn’t kill me doesn’t bother me,” I can still take it. If I croak, I croak. If I don’t, that’s good, too. I’ve just reread this letter and noticed that it is nothing but bellyaching from beginning to end. Don’t take it too much to heart. This too will pass. Many loving kisses from,

Your Georg

On one of those nights of long marches, a young soldier who had arrived with the last replacements and been at the front only a short time simply sat down and said, “I can’t walk any farther.”

The others kept marching past us, and I told him if he remained behind, he would fall into the hands of the Russians, who were gaining on us.

“They’ll just shoot you,” I said. “They aren’t taking any prisoners.”

“Let them,” he replied dully.

An officer came by and ordered the boy to get up, with no result. The officer pulled out his revolver and shouted, “Mensch, get up this minute or I’ll shoot you. This is an order!” But the soldier seemed to have gone deaf or at least to be in a different world.

At that moment I did something purely instinctive, without even considering the presence of the superior officer. I took off my wireless box, rifle, and gloves, grabbed the young soldier by his collar, placed myself squarely in front of him, and left, right, slapped him hard across the face. At the same time I roared, “Get up, you idiot!”

Slowly he raised himself, and, almost as if in a dream, he walked on, another soldier carrying his rifle.

During the following days, as we all became more exhausted, the order rang out a few more times, “Slapping squad to the rear!” And with that order, they meant me.

Before dawn on March 22, we dragged ourselves into Pervomaysk, a good-sized town on the river Bug. My regiment and many others were immediately ordered to secure a bridgehead. That entailed building a ring around the city so that each of the many thousands of Germans still within could retreat to the opposite bank of the river. The Russians, of course, were intent on taking Pervomaysk swiftly so that they could capture as many of us as possible.

Konrad and I were situated with the wireless on the ground floor of a two-story building on the eastern edge of the city. We were attempting to keep communications going between several companies and battalion headquarters, located a few houses away. Many of the nearby buildings were on fire, and smoke came through the broken window, making our eyes smart and tear. The city was being fought for street by street, house by house, and we could hear the battle raging in the distance.

By noon the racket sounded much closer. I was just wondering where the Russians had broken through when Konrad yanked out the cable connecting the wireless to the battery box and yelled, “Get out the back! The Russians are in front of the door.”

He was already on his way out the window, the battery box in one hand and a submachine gun in the other. I threw the wireless over my shoulder by one of its straps and grabbed my rifle, and the first bursts from the Russian submachine guns thwacked into the room as I vaulted out the window behind Konrad. The blast of a hand grenade blew me through the opening even faster than planned.

I scrambled to my feet and took off after Konrad across the open square. At the sound of heavy machine-gun fire, I glanced back to see that a tank had shoved its way through one of the ruins facing the square and was merrily shooting away at anything that moved. Zigzagging around debris and riddled vehicles, I made it into one of the side streets. Konrad had halted a few houses farther away to check his compass. He waved his arm in the direction ahead of us and we began running once more.

The street was darkened by heavy smoke. Some of the four-story houses on my right were enveloped in flames, and I could feel the blazing heat as I ran past. The noise on all sides was deafening: mortar hits, machine-gun fire, and the crackling and roaring of the flames from the burning houses.

All of a sudden, the wall of the house just to my right began tilting forward. The panic that seized me at that moment must also have endowed me with tremendous strength. In spite of the heavy wireless still hanging over my shoulder, I somehow ran faster.

A giant cloud of fire and dust exploded through the ground-floor window. The wall buckled at the second story, and all the masonry from the top floors, including the flaming roof beams, came tumbling down with a horrible earsplitting crash.

Some of the longest seconds of my life elapsed before my own legs and the monstrous air pressure propelled me just enough so that I was hit by only a few chunks of brick. I was tossed to the ground in a scorching cloud of dust. I staggered to my feet, checked my bones, and continued to run. Finally I overtook Konrad, who had paused in a doorway to catch his breath.

“This morning one of the bridges crossing the river was still intact,” he said. “If we can find it, and it’s still in one piece, we should be able to make it safely to the other side. The river can’t be too far away, maybe just a few blocks. Let’s go!”

We soon reached a wider street filled with scores of Germans, all running in the same direction. Without hesitating, we joined the rest. The Russians hadn’t penetrated this part of the city yet; nevertheless, all signs pointed to an uncontrolled full-scale flight by the Germans.

We reached the bridge and rejoiced to see it still whole, but it was choked up with soldiers and vehicles, all moving at a maddeningly slow pace toward the west bank. I could see Pioniere attaching explosive charges to the pilings. It had begun to rain.

After finally working our way to the opposite side, we were met by bellowing officers trying to bring some semblance of order or grouping into this milling mass of soldiers. It was a chaotic mixture of everything military: members of the tank corps without tanks, artillery soldiers with no cannons, wounded men on stretchers or still on foot, and officers of every rank. Some of the officers were hastily organizing battle units that they sent marching off in various directions.

“Hey, you two with the wireless, over here,” called a colonel to Konrad and me. A sergeant gave us ammunition and directed us to a column of about five hundred men who were already waiting to depart, bazookas and machine guns in hand.

“Column march!” rang out the command, and we were on our way. No one had any idea what our destination was. It was a sorry heap of hungry, battle-weary men who didn’t seem to care where they were headed, just as long as there was still someone to give orders and at least an impression that they knew why they were giving them.

The rain poured down steadily as we marched past huge amounts of war matériel, some shot up and some still in good condition. In a few minutes we had passed the last houses and ruins on the outskirts of town and were headed out into the flat, marshy fields.

There thousands of vehicles had been left standing up to their axles in the mire. Stinking horse cadavers with legs pointing stiffly toward the sky lay next to artillery cannons and mountains of ammunition crates that stretched as far as we could see. Bomb craters filled with water were everywhere.

A tremendous battle must have been waged in the section, but the Russians had evidently waived their right to this strip along the west side of the river, at least for now. It was obvious that all this equipment would fall into their hands sooner or later.

The ranks broke for a few minutes when we came up to an overturned truck. Crates full of canned foods lay open on the ground, and the eager soldiers helped themselves at will. Even the officers, as hungry as the rest of us, stooped to filling their pockets and bags. No one could say when circumstances would improve enough so that we could once again have a field kitchen and regular meals.

Back on the march, most of us opened one or two of the tins and gobbled up the contents: cold, greasy meat. At our backs I could hear the noise of continuing battle within the city. The Russians had brought in bombers and heavy artillery by now. No matter where I was headed, I felt very lucky to be walking along this far side of the river.

A series of heavy explosions made me glance back. Great chunks of steel were flying through the air in a huge black cloud—they had blown up the bridge.

Konrad made a face. “Certainly made it out of that one just in time.”

I nodded, thinking of Baby Schmidt and Moser, whom I hadn’t seen since we entered the city.

The officers urged us to more speed. After another half hour we reached our destination: a soggy airfield containing a few shot-up buildings. A troop carrier with its motors running stood a short distance away. The front portion of our column was ordered into the plane, while the remainder was told to keep ready; another aircraft would come later to pick us up.

Overcome by exhaustion and hopelessness, I stood watching as the plane began moving faster along the bumpy runway, finally leaving the ground to disappear in the rain clouds. I had very little hope of seeing another one.

We stood in the rain and waited. Konrad wandered to another group of soldiers and returned. “They claim the Russians have not only taken the city, but they’ve also built a larger circle around the entire area, including this airport, or what’s left of it. Could be just a rumor, though.”

I hadn’t expected any good news at this point. When Konrad didn’t get a response from me, he set off again on his search for news.

Looking around, I saw huge piles of crates and suitcases of every size, shape, and style stacked as high as small buildings. I sat down on one of the crates. Some soldiers had begun breaking open a few of the suitcases and were rummaging around in the contents. After listening for a while to amazed shouts, I became curious and shuffled over to see the reason for all the excitement.

What I saw was incredible. The suitcases were stuffed with French perfume and condoms; bottles of the most expensive cognacs and champagnes; elegant clothing for men and women, including tuxedos and French designer dresses; Russian icons of inestimable value; and old books bound in leather and gilt. There was also a thick roll of pure silk cloth and several dozen pairs of silk stockings, still in the original packaging.

We foot soldiers never owned more than the absolute essentials, and usually not even those. But the motorized branches of the service seldom came near the front lines. If the front disintegrated, those soldiers, and especially their officers, always had plenty of time to send their luggage back to the rear. As we now could see, this luggage contained not only priceless booty but also treasures brought from France and elsewhere, enabling the officers to maintain the good life, even on the Russian front.

This time the poor generals had miscalculated. The usual transport system hadn’t functioned in Pervomaysk. Everything had happened too quickly, and now those higher-ranking gentlemen’s only hope was to bring everything out by air.

I hadn’t seen anything civilized for six months. I had just escaped a very close encounter with the Russian bullets, and for weeks previous to this I had been unwashed, unshaven, covered with muck, and wet through to the skin, my tattered socks sticking to legs oozing pus. My surroundings had consisted primarily of blood, filth, and lice.

In such a state of mind and body, what an experience to open a suitcase and be assailed by the aroma of forgotten cleanliness and elegance. I stretched out my mud-encrusted hands to feel the unbelievable softness of pure silk. I reached into a completely different world and, almost without knowing what I was doing, I tore a strip from the roll of silk, wrapped it around a pair of stockings, and stuck the small package in my rear pants pocket.

At the sound of a low hum, I whirled around. A shadow appeared out of the heavy gray skies; a plane was coming in to land. “It’s a Ju 52,” somebody yelled.

An officer shouted, “Form ranks.”

We hurriedly grabbed a few more of the bottles lying around, and I snatched up a large hunk of smoked ham at the last second before running toward the plane.

I was more or less shoved into the aircraft. It was grotesque to see all that the soldiers were trying to carry or drag with them. Loud commands forced the majority to drop most of their loot before being permitted inside:

“No more. Move back. The rest of you will be picked up later.”

The motors whined; we bumped and rattled for half a mile and were at last airborne. I had begun the first airplane flight of my life, but whatever fear I might have felt was far outweighed by the wonder of having escaped the deadly situation below.

Russia, March 22, 1944

Dear Papi,

Right now I’m sitting in a warm hut again. I have slept a whole night and eaten my fill. My clothes are still full of mud, but otherwise I’m fine. Seven of us are waiting for the rest of the battalion, which should already have landed here in Balta by plane twelve hours ago. Eight empty bottles are standing on the table in front of me: two bottles French red wine, one bottle Cru Saint-Georges-Montagne, one bottle Weinbrand, one bottle Bordeaux Medoc, one bottle Jamaican rum, one bottle Stock egg cognac, and one bottle gin. We have consumed all of that since yesterday evening!

The days at the bridgehead in Pervomaysk were very hot. I’m not all that impressed by the war events, but you can believe I would rather not have experienced those three days. And then, all of a sudden we were flown to Balta. Here it feels as though the Germans are definitely beginning to lose control. I don’t know exactly what is ahead of me. It is still raining day and night.

I had to leave everything behind again. Now I have only my clothes and a few little things in my pockets. I organized a jacket, and in my breast pocket is a pair of silk stockings. I still have my wireless set, too. So now we’re waiting to see what the future will bring.

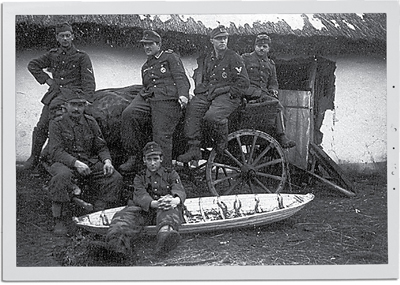

Communications squad, with Sergeant Konrad and Karl Haas in center of back row and me seated in front in the vakja (sledge).

I heard from a pilot that Vienna has been bombed. Please write me more details about this. It is important to me. Otherwise don’t worry. The war will be over soon, because it can’t go on much longer like this. Then I’ll come home again, and everything will be better. Give everyone my love, and please take care that at least everything remains okay at home. Many loving greetings.

Your Georg

The transport plane with the third group never arrived. We sat around for two more days, eating and drinking all the goodies the soldiers had managed to carry away from the Pervomaysk airport. Even Konrad got a little drunk, something I would never have thought possible.

“What regiment are you from?” was a common question. We were a mixture of thirty men from all sorts of branches, and not even half had any frontline experience. The rest were from transport, artillery, staff, engineer corps, and so on. Almost nobody knew anyone else from before, and I considered myself lucky to have Konrad nearby. He was sometimes gone for hours, trying to find out what was going to happen, but without success.

All of a sudden we were ordered to walk to a tiny railroad station, where we boarded a train with only five cars, and off we went. I caught the name of Birsula at one small station through which we passed. The ride finally ended in Slobodka, thirty kilometers farther southwest.

Immediately upon descending from the train, we hiked in groups of fifty men into the falling night. Some had light machine guns; a few others lugged lightweight mortars.

“I don’t like it,” said Konrad. “I don’t see any supply equipment whatsoever.”

“And as far as I can tell, you and I have the only wireless,” I replied.

It snowed the whole night. The temperature sank lower and lower, and the wind reached blizzard proportions. After the recent springlike temperatures, no one had his padded pants or jacket any longer. It was now the end of March, after all. We froze pitifully.

At daybreak, confronted with the sort of winter landscape we hadn’t seen for weeks, we dug ourselves in for the day. Konrad went spying.

When he returned he said, “No one has any idea of where we’re going or why. The unit that we were supposed to reinforce doesn’t exist, and the Russians seem to be all over the place.”

After the following day’s hike we reached an evacuated village. It huddled silently in the snow, empty of people and even chickens, but we did find some coverings to protect us from the biting cold. When we moved on, we resembled more than anything a group of armed beggars. Some had wrapped themselves up in colorful curtains, others had discovered some of the bright rugs typical of the region, and lucky were the men who had turned up a pabacha, a tall sheepskin wool cap. Various rags wrapped around our hands took the place of gloves.

In a letter to my parents I wrote,

We took eleven days for the stretch from Slobodka to somewhere near Tiraspol on the Dniester, all in night marches. The Russians were continually all around us. At night we kept looking for a hole, for a way out of the sack. In the mornings we were surrounded again. And all the time terrible cold and snowstorms so bad that we often had to lie flat on the ground so as not to be blown away. And absolutely nothing to eat.

I thought, I wish the powers that be could see their German soldiers now, wrapped in old carpets, muffled up in rags, unshaven, not having slept for days, on their knees begging the few locals for a piece of corn bread, too weak even to search the huts for food. As we came through one village, half the group stormed up to a woman who was carrying a pot of milk and fought over it. Very quickly we became fewer, the ammunition ran very low, and the cold became worse.

On our tenth day as a lost group behind the Russian lines, we were reduced to one hundred men. The highest ranking was a sergeant. Then scouts discovered a river ten kilometers to the west that might be our salvation, and we headed off in that direction without even waiting for nightfall.

The sun was already low in the west when I caught sight of an airplane headed in our direction. At almost the same moment the command rang out, “Low flyer, take full cover!” Everyone threw himself into the snow, but a minute later Konrad was up again waving his arms and shouting, “It’s a Fieseler Storch, a Storch!”

By the time the German light reconnaissance plane passed over us at a very low altitude, we were all on our feet and waving, full of hope. The plane made a loop and, when it was above us again, the pilot threw down six bags, two containing ammunition and the others filled with emergency rations. Each of us received two packages, neat little cardboard boxes about the size of a large book. The printed inscription read:

EMERGENCY RATIONS—FRUIT BREAD. IF COOKED WITH A LITTLE WATER MAKES PUDDING. WITH MORE WATER SOUP.

On April 3, we climbed up a small hill. Below lay the river Dniester, that goal we had been longing and striving for. It shone, a silver ribbon in the afternoon sun, running through the white winter landscape—a beautiful sight.

Enormous numbers of German vehicles and soldiers were assembled directly below us on the plain. The few available boats were occupied with ferrying some of them across the river.

Considering our appearance, it wasn’t surprising that the Germans shot at us until we were able to make ourselves known. Once past our own defense lines, we barely had time to eat a bite before we heard the deep hum of heavy diesel engines—the Russian tanks. They weren’t even visible yet, and not a shot had been fired, but everyone took off toward the river without even waiting for a command.

The water was about two kilometers away, and everyone ran, taking only rifles and leaving everything else behind. I still hauled the wireless on my back; Konrad carried the other box, and we ran as well as we could with this burden.

The tanks rolled up behind us, at least thirty of them, painted white and gleaming in the sun. Immediately they began firing into the fleeing masses with everything they had.

“Hopeless,” I said. “Nobody’s going to make it across that river.”

“We swim through,” Konrad said.

“Through that icy water? Good luck.”

I stopped, took the wireless off my back, removed a hand grenade from my belt, and was making ready to blow up the box when an open Volkswagen pulled up next to us. One of the three officers inside yelled, “You two with the set. Get inside fast!”

I grabbed the wireless; we jumped in and took off, driving wildly through the midst of all the fleeing soldiers and vehicles and the panic-stricken horses and cows that were running desperately in all directions.

Shells hit all around us, but by zigging and zagging around bomb craters and war matériel, we managed to draw closer to the river.

The sun was setting as we arrived at the bank. I asked myself why it happened to be us they had picked up, and what was the use anyway. There were no longer any boats to be seen, only despairing soldiers trying to decide whether to throw themselves into the freezing waters or wait to be finished off by the approaching tanks.

I was on the point of jumping out of the car when the officer at the wheel shouted, “Hold on!” The car rolled down a gentle slope to the river and right into the water. For a few seconds the current pulled us downriver, the car bobbing like a little boat. Suddenly a small propeller in the rear began to hum and, as if by magic, we chugged through house-high water fountains made by the shrapnel exploding around us and landed on the opposite side.

The car continued up the far bank and into the frozen fields and then finally stopped. Still without completely comprehending what had happened, I was waved over by one of the officers.

“Get into this crater. Send this message and wait for the answer,” he said, handing me a piece of paper. It was a request for new orders and position from division headquarters.

Some time later I remembered that back in Vienna I had once inspected an amphibian auto exactly like the one that had just transported us across the river; I hadn’t dreamed that such a vehicle would one day play a vital role in my life.

Very few others made it over the river. The majority remained behind.

April 10, 1944

My dear Mutti,

On the third of this month, we made a dramatic crossing of the Dniester, and after one day of rest we were back on the lines. Since then a major battle—tough, ruthless—has been raging for every meter. Each time we retreat, a counterattack follows shortly thereafter. And so it continues, back and forth.

The units are dissolving rapidly. Our division dwindled into a battle group and when that, in turn, became too small to be effective we were attached to another division. And so it continues. I almost never know the name of my commanding officer, since I belong to a different unit every few days.

Many are falling and wounded. The procession of wounded no longer has an end. I see more and more of those little hills with the crosses. The last little bit of humor is also disappearing, because blood is everywhere and everything is in shreds. All are becoming more nervous by the day. Add to that the weather, which is warmer now but melting all the snow and turning the whole country into puree again.

Thus we stand in the mud, day and night, everything wet and dirty. I have twelve boils on my leg, with no bandage because the medics need all the bandages for the wounded. My feet are lumps of mud, and everything—underwear, pants, and stockings—is equally slippery. My boots aren’t watertight either.

Yesterday it got to be too much for me, so I went back to the village to the doctor, who treated me and prescribed three days’ rest at the supply lines. Since telegraphists are lacking, they exchanged me with the regiment telegraphist. I had barely finished washing up when the Russians took the village. We had to get out in a hurry, so I spent Easter Sunday without a bite to eat, out in the open on a kilometer marker in the middle of the morass. Thank God the sun was shining a little.

In the evening the village came back into our hands by way of a counterattack, and since then it has been quiet. The stove is drying my clothes, and a chicken with potatoes is filling my stomach. What’s more, after a lice hunt (300–400) I slept like a baby the entire night.

Today is Easter Monday. The sun is shining gloriously, and everything looks a bit better again. A mail stoppage is in effect. I haven’t received any more mail from you since March 18. I’m curious how I’ll get rid of this letter. Don’t worry. I’ll get through somehow. Kisses,

Your Boy