LONG HOT SUMMER ON THE DNIESTER

June 1, 1944

Dear Mutti,

It seems as though it’s on purpose, that we’re not supposed to feel good even for a minute here at the front. In the winter we freeze, and the lice are always biting. During the summer it’s terrifically hot, and now it’s the fleas, mosquitoes, and flies biting for a change. These two seasons are separated by the periods of heavy mud and more lice. So the whole year through a soldier never has one moment when he can lie down and really feel contented.

Last night two other men and I were sent up front to company headquarters. My task is to provide wireless connections when the telephone lines to the battalion are interrupted. We lie sixty meters away from the Dniester, which is only a stone’s throw wide at this point. Ivan is sitting on the opposite bank. In the evening we can hear the Russians talking quite clearly.

Last night we were busy building bunkers, since they are the only place where one can be halfway secure. What’s more, there aren’t so many mosquitoes in the bunkers, and it is a few blessed degrees cooler. The heat makes us quite weak, especially since our only drinking liquid is one canteen of coffee per day. We can’t gather water from the river, as the Russians would shoot us down immediately. The closest well is three kilometers away. So we sweat all day long doing nothing and then sweat through the nights while we dig.

It is almost impossible to wash oneself here. Very seldom, and then only by chance, do we come upon sufficient water. Thank God they keep relieving me every eight days so I can get back to the battalion.

The surroundings are actually quite pretty: endless groves of fruit-filled trees, meadows, and woods, all completely without a sign of human effort. On the whole it looks as though this is going to be a permanent situation. The Russians are making no further attacks but just keep shooting mortars over the river at us, day and night. Casualties do occur from time to time, but they are minimal.

Usually it’s the newcomers who fall. Those who have been here longer know only too well where and when they should move about freely and when to throw themselves in the dirt.

Very little mail or food is getting through. We make soups from wild birds, cook up some thistle spinach, or brew an herb tea. But all this costs us such effort; one becomes so slack and weary here. The only consolation is that I’ll be getting furlough in a few weeks. The day before yesterday my former troop leader went on leave. He may call you, if he doesn’t forget.

Dear Mui, it is really time for me to get back home again, because I realize that I’m turning into a complete idiot here. I can’t even write properly anymore. I have no interest in anything. The degrees of depression, with their accompanying signs, such as becoming filthy and stupid, no longer writing letters, etc., can be seen quite strongly in some of the soldiers. Along with these other symptoms, our cheeks become hollow and our eyes look so empty. Movements are sluggish and indifferent. Mouths never twist themselves into a smile. I hope all that won’t happen so quickly with me.

As an antidote, I pose complicated math problems to myself and then exert great effort in trying to solve them. I look for someone with whom I can have an intelligent conversation. Or I try to check out the separate parts of my rifle from an engineering point of view; by that I mean figure out the purpose of each part and its shape. All of this takes great concentration but seems to be the only way to remain halfway fresh. It has a horrible effect, you see, when I observe the stubborn, stupid, sunken faces of the others.

Enough for today. I’ll write again soon. My love to Papi, and tell Vroni that I wish her much happiness and success in the coming weeks. [Author’s note: My sister was about to give birth.]

Your Georg

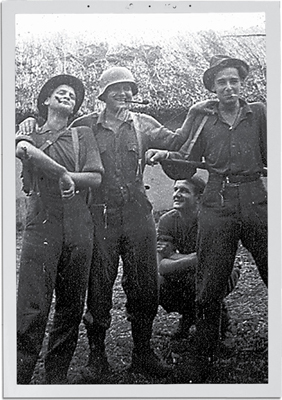

(From left) Unidentified soldier, Baby Schmidt, and me, with Konrad kneeling behind.

The East, June 6, 1944

Dear Mutti,

It is so still and peaceful here since the Russians have stopped shooting those mortars. The only shots come now and then from a sharpshooter. Tomorrow night, after eight days’ duty with the company, I’ll be relieved and head back to the battalion. The food is better there, but more important, the sharpshooters can’t shoot that far. Right now a pleasantly cool little breeze is blowing, and that feels so good to all of us. During the day this damp heat really does us in.

Today news of the beginning of the Allied invasion of Normandy came through the radio. A sigh went through the whole front, for everyone hopes that an end will soon be in sight, let it be what it will. Heavy debates and verbal duels are raging everywhere. No one knows anything, but everyone has an opinion and believes his is the correct one. Oh well; it’s all the same to me, because I know that the Atlantic wall is impregnable, that the English and American soldiers don’t know anything about shooting, that Germany is winning on all fronts for Europe because the wheels are rolling for victory, the thousand-year victory. So I have neither scruples nor doubts, fear neither hell nor the devil, but rather wait for my supper that won’t arrive for four and a half hours and will surely consist of an unsalted water soup with four or five potatoes. Right now we are blessed with ration level 4, the minimum for just keeping us alive.

The sun is going down in front of me, and I have been observing that the pink of the sky did not blend at all well with the juicy green of the trees. The effect was quite kitschy.

I have to put the mosquito net over my head because the beasts are starting to become unpleasant. I might report, as a special event, that I found only two lice today. That pleases me very much, for, after all, I haven’t been deloused for one and a half months and have had periods since then with a great many lice.

I read in the newspaper of a major bombing attack on Vienna. Please write me where they hit. (Twenty-sixth of May.) A few good kisses from your Georg, whom nothing can hit because he sneaks through, like the ghost of a thread!

My division was part of the Sixth Army and formed the most southerly flank of the front. At this time, Romania and the southern Ukraine were strategically unimportant for the Russians. They put their main forces into action farther north, in the front’s midsection, and succeeded in pushing deeply into Poland in battles that involved high casualties on both sides.

Romania had been occupied by the Germans toward the beginning of the war and afterward fought, if unenthusiastically, on their side. The Russians speculated that probably the entire southern flank could be overrun with a minimum of effort. That was why, with the exception of occasional mortar fire and a few locally confined skirmishes, the front remained very tranquil where we were during the spring and summer of 1944.

As the days grew warmer, an abundance of fruit became ripe, and the German soldiers began to recover from the hardships of the preceding months. The fact that mail or rations seldom made it to our position was primarily the fault of the 250,000 partisans who were busily blowing up trains and bridges at the rear.

Following the brief weeks of mild spring, the heat, mosquitoes, and boredom began to do their worst. The lack of water, the bad rations, and the slowly dawning realization that we were sitting in a trap where our connection to the rear could be cut off at any time began to wear us down.

The East, June 18, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Today in the Wehrmacht’s report we heard that the new German weapon has been put into use, also news of the bombardment of Vienna. Then I received your letter where you write about your gallbladder attack, etc. All in all, I’m in a pretty bad mood. It really looks as though this war will be fought until the last German croaks. The only consolation is that future historians can write about how the Germans fought to the last drop of blood. Their eternal glory is assured. We all end up heroes here, whether we want to or not.

By now most of my comrades wish they had never heard of Germany, but rather had lived out their eighty years as naked savages under a palm tree. Then perhaps their souls would not have become so black and bloodstained. It is very unpleasant for us to continue fighting in undetermined battle actions, while at home the cities are falling. There’s still no end in sight, until one day some German, American, or Englishman will notice that he is the last one in the slaughter field—the victor—but nevertheless unhappy and despairing.

Officer Zimmerman probably won’t be coming, since evidently all those who have left on furlough until now are being sent to France. If you absolutely want to send a one-hundred-gram package, then please include sweet things, white thread (no needles), map sections of the French and Italian fronts showing the names of the most important towns, and, if you can dig it up, a lighter. It can be old and unmodern, but it’s important that the fluid doesn’t evaporate too quickly by itself. Otherwise I don’t need anything. I would appreciate if you would include with your letters a few pages from an old math or engineering textbook, beginning with equations, so I could have something sensible to do here.

Dear Mui, try to become strong and healthy again, and don’t worry too much. What can happen to me anyway? What’s gone is gone.

1,000 Bussis, Your Georg

The East, June 24, 1944

Dear Mui,

The long deliberations and purchases for packages and furlough were all for nothing. The noncom won’t be visiting you, and I won’t be going on furlough. At least I now have a very nice substitute here—the fruit—for the packages you wanted to send. Cherries abound, and in the next few days the currants and gooseberries will be ripe. Then the apricots, peaches, and plums will come along. The trees are already bending over.

We are now in a new location out in the open, two kilometers outside a town. Today I spent the whole day in Criulem, obtaining boards, doors, and chairs for our staff bunker. While occupied with this task, I went up into an attic, and a young Romanian of about twenty years fell into my hands. He really has no excuse for being here at the front, because all the civilians have been evacuated, so he had to do whatever I said. I made him climb up a cherry tree in the Russian line of fire to pick two buckets of cherries for me, and afterward I let him go. Then I stewed the cherries, masses of them, in three buckets. Now I’m sitting here with sticky fingers at the door of a cellar, ready to jump down, because Ivan is shooting pretty heavily.

Around eleven tonight a vehicle will come to pick up all the other stuff and me.

Boy, will my buddies lick their chops when they see what a treat I’m bringing. In a few days I’m going forward to the company again, and perhaps I’ll stay there longer than eight days, because my relief was killed. It doesn’t make that much difference to me where I am. The only disadvantage is that the food is worse up front, and if the Russians come I’ll have to run a little faster. The heat and the flies are unbearable. If at least one had the chance to wash all over every day—but that’s just not possible.

Dear Mutti, it’s so hard to write today—the heat, the full stomach. You know I’m still alive and am doing fine, and with that the purpose of this letter has been accomplished. If you could dig up a few watercolor paints and some glue (Uhu, Sintetikon, but not Pelikanol), I’d be very grateful. I have brushes, etc. Loving greetings to Papi and Vroni.

Your Georg

One day during this very hot, dry period I was sitting listlessly in my bunker on a wobbly stool in front of the wireless. I was bored and surrounded by thousands of flies. There was nothing to read, no one to talk to, and I had already written a letter home.

I pulled a piece of bread out of my sack and spread it with some of the softened artificial honey. A drop of the sugary syrup fell on the top sheet of the tablet of forms for recording incoming messages, and a fly immediately landed next to the drop and began eating. Still bored, I sat and watched as a second fly landed next to the first, and very soon the honey drop was completely surrounded by flies.

With my index finger, I lengthened the drop of honey across half the page. Barely a minute passed before the borders around the finger-thick strip of honey were fully occupied. I counted forty flies, and then I started to wake up and become interested. It was beginning to dawn on me how I might become master of the plague of flies.

I took a fresh page, made ten parallel honey lines with my finger, and then waited. It definitely wasn’t more than ten minutes before 800 flies had taken their places in an orderly fashion around each of the lines, just like guests seated around a long banquet table. Slowly I stood up and carefully reached for a large piece of cardboard. Raising it in the air, I took careful aim and, wham, brought it down on the feast. Far surpassing the little tailor in the old folktale, I had slain 800 at one blow. Not a very pretty sight though, to say the least. After I had repeated this procedure two more times, the fly population had sunk so drastically that I had difficulty in my fourth and final attempt even to lure fifteen flies to the paper. With that the plague of flies in our bunker ceased, until there was a change in our diet and a kind of liverwurst was substituted for the artificial honey.

I tried using sugar water as bait for a while, but the results didn’t begin to compare with those previous. Evidently the Romanian flies had developed a special fondness for the National Socialistic brand of artificial honey.

The East, June 30, 1944

My dear folks,

I’m up front with the company again. I received quite a bit of mail from you during the past few days and was glad to hear that everything turned out all right with Vroni and baby. Tonight the company chief and I went swimming in the river. It is only fifteen meters wide, with Ivan situated on the opposite bank, but the weather is so unbearably hot and humid.

We had two machine guns set up on the bank, plus five men armed with hand grenades. They shot a little bit at first, and then we dived in. It was simply wonderful! Soon afterward a lovely rain, the first in almost two months, began falling. We all breathed a sigh of relief. When it first warmed up last spring, we used to lie in the sun, but now we avoid every sunbeam. One can become quite stupid and the brain dries up completely in this heat.

There are so many cherries and giant mulberries. Runny bowels are the order of the day. I hear the Wehrmacht’s report daily, so I’m always up to date. Thus I know immediately whenever Vienna has been bombed. It takes a long time, though, until you get to hear just what all was destroyed.

Except for that worry, I’m fine. Ivan isn’t stirring at all, just a shot now and then. It doesn’t upset me at all anymore. It is very funny the way the others are constantly bellyaching if they are lying uncomfortably, or if they haven’t had enough sleep, or if the food is bad, or if the Russian artillery sends off a round. That’s because 95 percent of those with me now are newly arrived and have never been in Russia.

As for me, if I’m not feeling so great, I just draw upon a memory of a day from last winter by comparison, and immediately I can see how fantastic everything is right now. Last winter did have one advantage. If I should ever be very badly off sometime in the coming years, I now know exactly how to manage with a hunk of bread for half a week and a newspaper for a blanket. I understand now that I don’t need a house all year long or regular meals, to say nothing of a bed or other such luxuries. All of this has a very comforting effect, because I’m not convinced that the situation is going to be all that rosy in the years following the war.

Am running out of paper and I have to be thrifty with it. I am waiting longingly for the math book pages. Many loving greetings,

Your Georg

July 2, 1944

Dear Mutti,

The days pass by very monotonously. Always the same activities, the same weather, the same too little to eat (beans, peas, lentils, beans, peas, etc.), and hardly ever any cause for laughter.

I’m working now on the art of being happy and taking delight in very small things. The average person lives here completely without joy. And if there is an occasion for happiness, when it’s repeated it has already lost its effect. Thus, everyone rejoices the first time he sits in a tree full of cherries, but the next time such an experience is sullenly taken for granted. Tempers can even flare up if everything isn’t exactly the same.

The radio is another case in point. I remember it seemed a miracle after three or four months to hear music again for the first time. Now we have a radio that plays half the day, but everyone is so indifferent, no longer capable of rejoicing.

Recently I’ve been trying, with increasing success, to submerge myself into even the least important things and thereby to seize great happiness. Thus, with the necessary concentration and love, you can be transported into the heights of rapture simply at the sight of a tiny bug on the lid of your mess kit. Others perhaps might have thrown him away or squashed him, with a bitter twist of the mouth.

With practice, one can so intensify this feeling that afterward the big things such as war, death, hunger seem very tiny and unimportant. So one doesn’t necessarily have to have a whole pair of pants or a full butter jar. The disagreeable things that bring the monotony so crassly into consciousness every day become so unimportant that it is truly a pleasure to observe how one can defend oneself against those chapters of life. I think the haiku poets are the masters in this, but I can see that it is not impossible to learn. I don’t know whether it also couldn’t have something to do even with religion.

Maybe these lines will seem completely unintelligible to you. In that case, I just haven’t managed to catch hold of the right words. If you do understand, however, what I mean by all this, then you have every reason to be happy that your son is on the point of learning a way never again to be bored, bad-humored, or sad while sitting in a hole in the ground. In this spirit,

Your Georg