The ability to read and write is essentially a cultural invention, albeit one of enormous significance. It enables humans to exchange ideas without face-to-face contact and results in a permanent record for posterity. It is no coincidence that our historical knowledge of previous civilizations is derived almost entirely from literate cultures. Literacy, unlike speaking, requires a considerable amount of formal tuition. As such, literacy provides cognitive neuroscience with an interesting example of an “expert system.” Learning to read and write may involve the construction of a dedicated neural and cognitive architecture in the brain. But this is likely to be derived from a core set of other skills that have developed over the course of evolution. These skills include visual recognition, manipulation of sounds, and learning and memory. However, it is inconceivable that we have evolved neural structures specifically for literacy, or that there is a gene specifically for reading (Ellis, 1993). Literacy is too recent an invention to have evolved specific neural substrates, having first emerged around 5,000 years ago. Moreover, it is by no means universal. Universal literacy has only occurred in Western societies over the last 150 year, and levels of literacy in developing countries have only changed substantially over the last 40 years (UN Human Development Report, 2011). Of course, the brain may acquire, through experience, a dedicated neural structure for literacy, but this will be a result of ontogenetic development (of the individual) rather than phylogenetic development (of the species).

The Origins and Diversity of Writing Systems

Writing has its historical origins in early pictorial representation. The point at which a picture ceases to be a picture and becomes a written symbol may relate to a transition between attempting to depict an object or concept rather than representing units of language (e.g. words, phonemes, morphemes). For example, although Egyptian hieroglyphs consist of familiar objects (e.g. birds, hands), these characters actually denote the sounds of words rather than objects in themselves. As such, this is a true writing system that is a significant step away from the pictorial depictions of rock art.

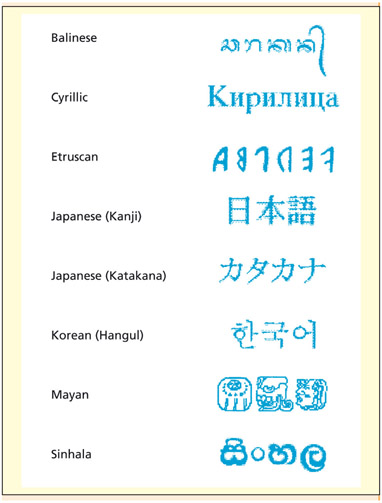

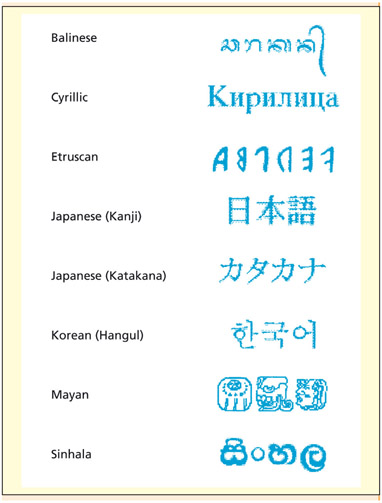

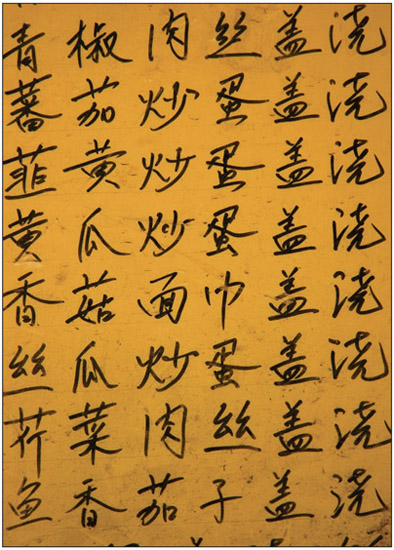

The diversity of written language.

Different cultures appear to have made this conceptual leap independently of each other (Gaur, 1987). This accounts for some of the great diversity of writing systems. The earliest writing system emerged between 4,000 and 3,000 BC, in what is now southern Iraq, and was based on the one-word–one-symbol principle. Scripts such as these are called logographic. Modern Chinese and Japanese Kanji are logographic, although they probably emerged independently from the Middle Eastern scripts. Individual characters may be composed of a number of parts that suggest meaning or pronunciation, but the arrangement of these parts is not linear like in alphabetic scripts.

Other types of script represent the sounds of words. Some writing systems, such as Japanese Kana and ancient Phoenician, use symbols to denote syllables. Alphabetic systems are based primarily on mappings between written symbols and spoken phonemes. All modern alphabets are derived from the one used by the Phoenicians; the Greeks reversed the writing direction to left–right at some point around 600 BC.

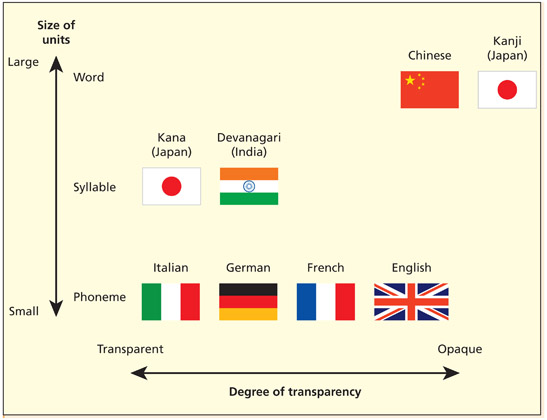

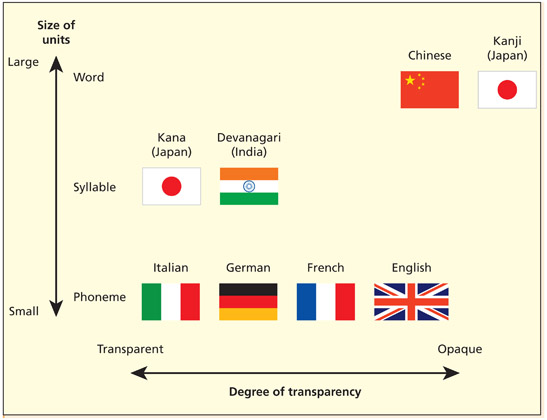

Writing systems can be classified according to the size of the linguistic unit denoted (phoneme, syllable, word) and the degree of regularity (or transparency) between the written and spoken forms. From Dehaene, 2010, p. 117

The term grapheme is normally used to denote the smallest meaningful unit of written language, analogous to the term “phoneme” in spoken language. In languages such as English, this corresponds to individual letters (Henderson, 1985), although the term is also often used to refer to letter clusters that denote phonemes (e.g. in the latter definition, the word THUMB would have three graphemes: TH, U, and MB, corresponding to the phonemes “th,” “u,” and “m”).

It is important to note that not all alphabetic scripts have a very regular mapping between graphemes and phonemes. Such languages are said to be opaque. Examples include English and French (consider the different spellings for the words COMB, HOME, and ROAM). Not all irregularities are unhelpful. We write CATS and DOGS (and not CATS and DOGZ), and PLAYED and WALKED (not PLAYED and WALKT) to preserve common morphemes for plural and past tense, respectively. However, other irregularities of English reflect historical quirks and precedents (Scragg, 1974). For example, KNIFE and SHOULD would have been pronounced with the “k” and “l” until the seventeenth century. Moreover, early spelling reformers changed spellings to be in line with their Greek and Latin counterparts (e.g. the spelling of DETTE was changed to DEBT to reflect the Latin “debitum”). Other languages, such as Italian and Spanish, have fully regular mappings between sound and spelling; these writing systems are said to be transparent.

Cognitive mechanisms of visual word recognition

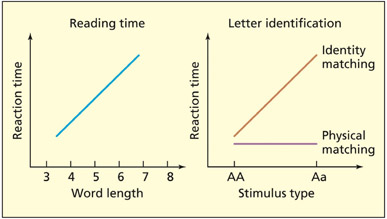

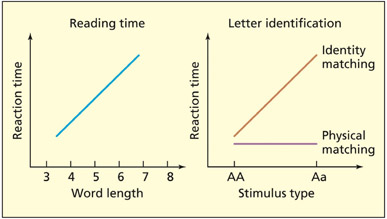

One of the earliest findings in the study of visual word recognition was the fact that there is little processing cost, in terms of reaction times, for recognizing long relative to short words (Cattell, 1886). Of course, reading a long word out loud will take longer than reading a short word aloud, and the preparation time before saying the word is also related to word length (Erikson et al., 1970). But the actual visual process of recognizing a word as familiar is not strongly affected by word length. This suggests a key principle in visual word recognition— namely, that the letter strings are processed in parallel rather than serially one by one. Recognizing printed words is thus likely to employ different kinds of mechanisms from recognizing spoken words. All the information for visual word recognition is instantly available to the reader and remains so over time (unless the word is unusually long and requires an eye movement), whereas in spoken word recognition the information is revealed piecemeal and must be integrated over time.

Key Terms

Word superiority effect

It is easier to detect the presence of a single letter presented briefly if the letter is presented in the context of a word.

Lexical decision

A two-way forced choice judgment about whether a letter string (or phoneme string) is a word or not.

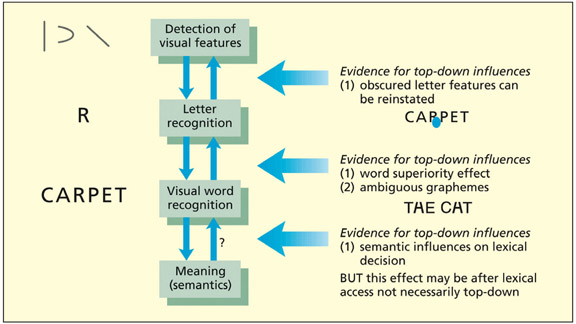

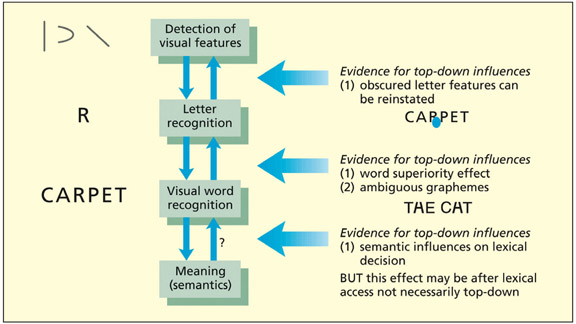

Visual word recognition also appears to be greater than the sum of its parts (i.e. its constituent letters) in so far as patterns across several letters are also important. If one is asked to detect the presence of a single letter (e.g. R) presented briefly, then performance is enhanced if the letter is presented in the context of a word (e.g. CARPET), or a nonsense letter string that follows the combinatorial rules of the language (e.g. HARPOT) than in a random letter string (e.g. CTRPAE) or even a single letter in isolation (Carr et al., 1979; Reicher, 1969). This is termed the word superiority effect. It suggests that there are units of representation corresponding to letter clusters (or known letter clusters comprising words themselves) that influence the visual recognition of letters and words. Intracranial EEG recordings suggest that word and word-like stimuli are distinguished from consonant strings after around 200 ms in the mid-fusiform cortex (Mainy et al., 2008). Scalp EEG recordings reveal a similar picture but suggest an interaction between visual processes and lexical-semantic processes such that stimuli with typical letter patterns can be discriminated at around 100 ms (e.g. SOSSAGE compared with SAUSAGE), but with words differing from nonwords at 200 ms (Hauk et al., 2006). This later effect was interpreted as top-down activity from the semantic system owing to the EEG source being located in language rather than visual regions.

The evidence cited above is often taken to imply that there is a role of top-down information in visual word recognition. Stored knowledge of the structure of known words can influence earlier perceptual processes (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1981; Rumelhart & McClelland, 1982). Although this view is generally recognized, controversy still exists over the extent to which other higher-level processes, such as meaning, can influence perceptual processing. One commonly used task to investigate word recognition is lexical decision in which participants must make a two-way forced choice judgment about whether a letter string is a word or not. Non-words (also called pseudo-words) are much faster to reject if they do not resemble known words (Coltheart et al., 1977). For example, BRINJ is faster to reject than BRINGE.

According to many models, the task of lexical decision is performed by matching the perceived letter string with a store of all known letter strings that comprise words (Coltheart, 2004a; Fera & Besner, 1992; Morton, 1969). This store is referred to as the visual lexicon (also the orthographic lexicon). Under this account, there is no reason to assume that meaning or context should affect tasks such as lexical decision. However, such effects have been reported and could potentially provide evidence for semantic influences on word recognition.

Key Term

Visual lexicon

A store of the structure of known written words.

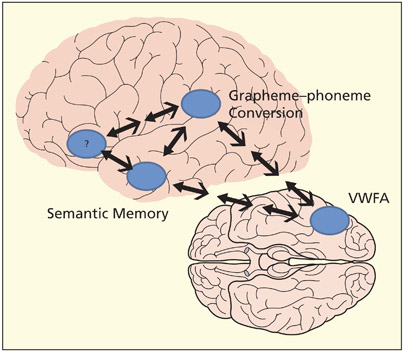

A basic model of visual word recognition showing evidence in favor of top-down influences.

Meyer and Schvaneveldt (1971) used a modified lexical decision in which pairs of words were presented. Participants responded according to whether both letter strings were words or otherwise. Semantically related pairs (e.g. BREAD and BUTTER) were responded to faster than unrelated pairs (e.g. DOCTOR and BUTTER). A number of potential problems with this have been raised. The first concerns the nature of the lexical decision task itself. It is possible that it is not a pure measure of access to the visual lexicon but also entails a post-access checking or decision mechanism. This mechanism might be susceptible to semantic influences, rather than the visual lexicon itself being influenced by top-down effects (Chumbley & Balota, 1984; Norris, 1986). Moreover, it has been argued that these effects may not be truly semantic at all. If participants are asked to associate a word with, say, BREAD, they may produce BUTTER but are unlikely to produce the word CAKE, even though it is semantically related (similarly, ROBIN is more likely to elicit HOOD as an associate than BIRD). Shelton and Martin (1992) found that associated words prime each other in lexical decision, but not other semantically related pairs. This suggests that the effect arises from inter-word association, but not top-down semantic influence.

The visual word form area

As already noted, most models of visual word recognition postulate a dedicated cognitive mechanism for processing known words (a visual lexicon). Although these models have been formulated in purely cognitive terms, it is a short logical step to assume that a dedicated cognitive mechanism must have a dedicated neural architecture. This was postulated as long ago as 1892 (Dejerine, 1892), although it is only in recent times that its neural basis has been uncovered.

Characteristics of the Visual Word Form Area

- Responds to learned letters compared with pseudo-letters (or false fonts) of comparable visual complexity (Price et al., 1996b)

- Repetition priming suggests that it responds to both upper and lower case letters even when visually dissimilar (e.g. “a” primes “A” more than “e” primes “A”) (Dehaene et al., 2001)

- Subliminal presentation of words activates the area, which suggests that it is accessed automatically (Dehaene et al., 2001)

- Electrophysiological data comparing true and false fonts suggests that the region is activated early, at around 150–200 ms after stimulus onset (Bentin et al., 1999)

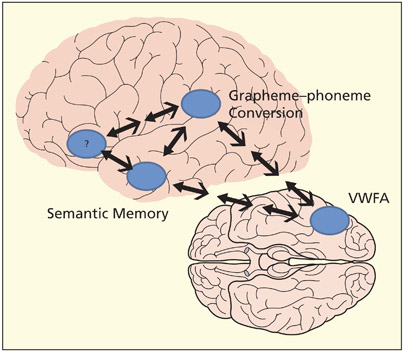

A number of functional imaging studies have been reported that argue in favor of the existence of a so-called visual word form area, VWFA (Dehaene & Cohen, 2011; Petersen et al., 1990). This area is located in the left mid occipitotemporal gyrus (also called fusiform gyrus). Some of the response characteristics of this region to visual stimuli are listed on the next page. Meaningless shapes that are letter-like do not activate the region. This suggests that the neurons have become tuned to the visual properties of known letters and common letter patterns (Cohen et al., 2002). This particular region of the brain lies along the visual ventral stream, and neurons in this region are known to respond to particular visual features (e.g. shapes, junctions) and have large receptive fields (i.e. do not precisely code for location of objects).

The visual word form area also responds to nonwords made up of common letter patterns as well as to real words, although the degree of this activity may be task dependent (e.g. reading versus lexical decision; Mechelli et al., 2003; see also Fiebach et al., 2002). The responsiveness to nonwords has cast some doubt over whether this region is actually implementing a visual lexicon (i.e. a store of known words). One reason a neural implementation of a visual lexicon could respond to nonwords, at least to some degree, as well as real words is because nonwords can only be classified as such after a search of the visual lexicon has failed to find a match (Coltheart, 2004a). Thus, a neural implementation of a visual lexicon could be activated by the search process itself, regardless of whether the search is successful or not (i.e. whether the stimulus is a word or nonword). Dehaene and colleagues (2002) initially argued that the VWFA contains a prelexical representation of letter strings, whether known or unknown. Subsequent evidence led them to refine this to include several different sized orthographic chunks including words themselves (Dehaene & Cohen, 2011). For instance, the BOLD activity in the VWFA is unaffected by the length of real words suggesting that the letter pattern might be recognized as a single chuck (Schurz et al., 2010). The same isn’t found for nonwords which implies that their recognition is not holistic. Moreover, BOLD activity in the VWFA differentiates real words from the same-sounding nonwords (e.g. taxi versus taksi; Kronbichler et al., 2007). This suggests that word-based activity is indeed orthographic rather than phonological.

Given that visual recognition of letters and words is a culturally dependent skill, why should it be the case that this same part of the brain becomes specialized for recognizing print across different individuals and, indeed, across different writing systems (Bolger et al., 2005)? Possible answers to this question come from studies examining the function of the VWFA in illiterate people and also in people who do not read visually (Braille readers). Dehaene et al. (2010) compared three groups of adults using fMRI: illiterates, those who became literate in childhood, and those who became literate in adulthood. They were presented with various visual stimuli such as words, faces, houses, and tools. Literacy ability was correlated with increased activity of the left VWFA, and there was a tendency for literacy to reduce the responsiveness of this region to faces (which displaced to the right hemisphere). The basic pattern was the same if literacy was acquired in childhood or adulthood. In another fMRI study, congenitally blind individuals were found to activate the left VWFA when reading Braille relative to touching other kinds of object (Reich et al., 2011). Thus the VWFA is not strictly visual but may preferentially process certain types of shape. The tendency for it to be predominantly left-lateralized may arise from the need for it to establish close ties with the language system. Indeed literates, relative to illiterates, show greater top-down activation of the VWFA in response to processing speech (Dehaene et al., 2010). Further evidence that the laterality of the VWFA is dependent on the location of the speech system comes from studies of left-handers. Whereas right-handers tend to have left lateralization for speech production, left-handers show more variability (some on the left, others on the right or bilateral). In left-handers, the lateralization of the VWFA tends to correlate with the dominant lateralization of speech observed in the frontal lobes (Van der Haegen et al., 2012). This again suggests that the development of a putatively “visual” mechanism is linked to important nonvisual influences.

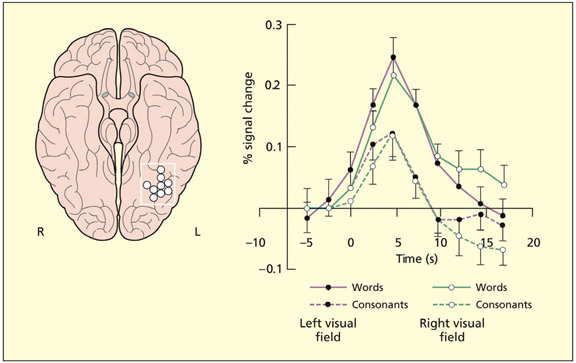

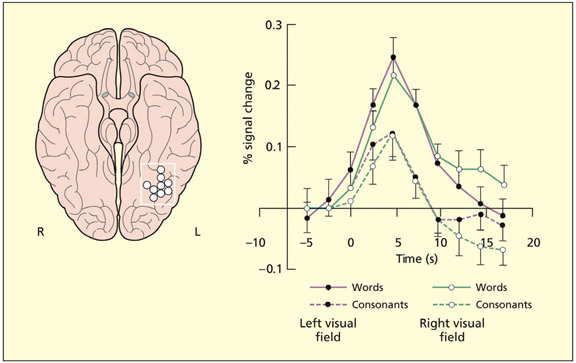

The visual word form area is located on the rear under-surface of the brain, primarily in the left hemisphere. It responds to written words more than consonant strings, and irrespective of whether they are presented in the left or right visual field.

Other researchers have argued that the existence of the visual word form area is a “myth”, because the region responds to other types of familiar stimuli, such as visually presented objects and Braille reading, and not just letter patterns (Price & Devlin, 2003, 2011). These researchers argue that this region serves as a computational hub that links together different brain regions (e.g. vision and speech) according to the demands of the task. This, of course, is not completely incompatible with the view described by others: i.e. that the region becomes tuned to certain stimuli over others and interacts with the language system (bidirectionally).

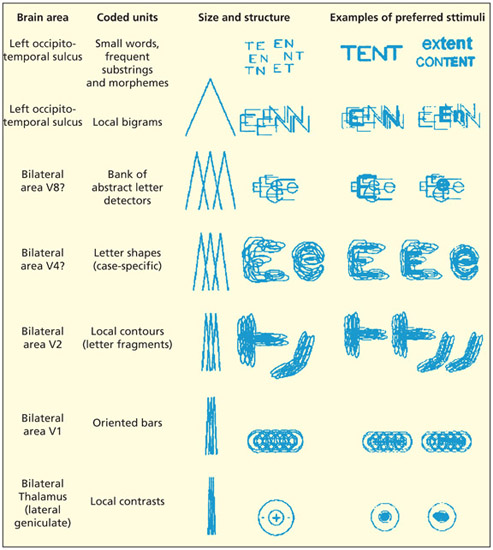

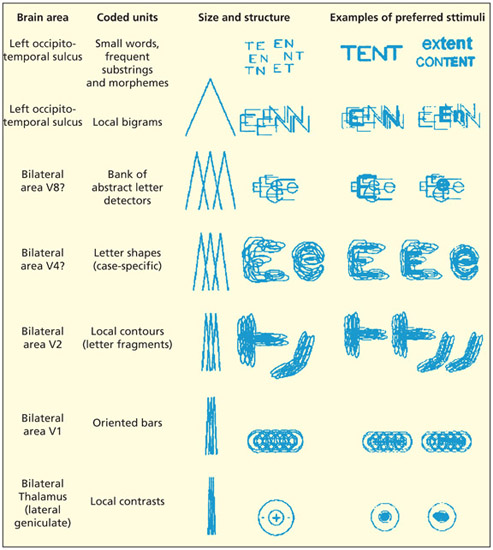

Visual word recognition can be considered as a hierarchy that progresses from relatively simple visual features (e.g. based on processing of contrast and line orientation), to shape recognition, to culturally-tuned mechanisms that, for instance, treat E and e as equivalent. It is still debated as to what sits at the very top of the hierarchy: it may consist of whole words (i.e. a lexicon) or common letter patterns.

Other support for the idea that the VWFA is important for visual word recognition in particular, rather than visual perception or language in general, comes from neuropsychological evidence. It has also been argued that damage to this region produces a specific difficulty with reading—namely, pure alexia or letter-by-letter reading (Pflugshaupt et al., 2009). This is considered in the next section.

Pure alexia or “letter-by-letter” reading

Imagine that a patient comes into a neurological clinic complaining of reading problems. When shown the word CAT, the patient spells the letters out “C,” “A,” “T” before announcing the answer—“cat.” When given the word CARPET, the patient again spells the letters out, taking twice as long overall, before reading the word correctly. While reading is often accurate, it appears far too slow and laborious to be of much help in everyday life. Historically, this was the first type of acquired dyslexia to be documented and it was termed pure alexia to emphasize the fact that reading was compromised without impairment of spelling, writing or verbal language (Dejerine,1892). It has been given a variety of other names, including “letter-by-letter reading” (Patterson & Kay, 1982), “word form dyslexia” (Warrington & Shallice, 1980) and “spelling dyslexia” (Warrington & Langdon, 1994).

Pure alexia is an example of a type of peripheral dyslexia. Peripheral dyslexias are believed to disrupt processing up to the level of computation of a visual word form (Shallice, 1988) and also include various spatial and attentional disturbances that affect visual word recognition (Caramazza & Hillis, 1990a; Mayall & Humphreys, 2002). This stands in contrast to varieties of central dyslexia that disrupt processing after computation of a visual word form (e.g. in accessing meaning or translating to speech). These will be considered later on in this chapter.

Key Terms

Pure alexia

A difficulty in reading words in which reading time increases proportionately to the length of the word.

Peripheral dyslexia

Disruption of reading arising up to the level of computation of a visual word form.

Central dyslexia

Disruption of reading arising after computation of a visual word form (e.g. in accessing meaning, or translating to speech).

The defining behavioral characteristic of pure alexia is that reading time increases proportionately to the length of the word (the same is true of nonwords), although not all patients articulate the letter names aloud. This is consistent with the view that each letter is processed serially rather than the normal parallel recognition of letters in visual word recognition. At least three reasons have been suggested for why a patient may show these characteristics:

- It may be related to more basic difficulties in visual perception (Farah & Wallace, 1991).

- It may relate to attentional/perceptual problems associated with perceiving more than one item at a time (Kinsbourne & Warrington, 1962a).

- It may relate specifically to the processing of written stimuli within the visual word form system or “visual lexicon” (Cohen & Dehaene, 2004; Warrington & Langdon, 1994; Warrington & Shallice, 1980).

As for the purely visual account, it is often the case that patients have difficulty in perceiving individual letters even though single-letter identification tends to outperform word recognition (Patterson & Kay, 1982). Some patients do not have low-level visual deficits (Warrington & Shallice, 1980), but, even in these patients, perceptual distortions of the text severely affect reading (e.g. script or “joined-up” writing is harder to read than print). Deficits in simultaneously perceiving multiple objects are not always present in pure alexia, so this cannot account for all patients (Kay & Hanley, 1991). Other studies have argued that the deficit is restricted to the processing of letters and words. For example, some patients are impaired at deciding whether two letters of different case (e.g. “E,” “e”) are the same, but can detect real letters from made-up ones, and real letters from their mirror image (Miozzo & Caramazza, 1998). This suggests a breakdown of more abstract orthographic knowledge that is not strictly visual.

Some scripts are particularly difficult for letter-by-letter readers. Note the perceptual difficulty in recognizing “m” in isolation.

Many researchers have opted for a hybrid account between visual deficits and orthography-specific deficits. Disruption of information flow at various stages, from early visual to word-specific levels, can result in cessation of parallel letter reading and adoption of letter-by-letter strategies (Behrmann et al., 1998; Bowers et al., 1996). These latter models have typically used “interactive activation” accounts in which there is a cascade of bottom-up and top-down processing (see the figure on p. 297). This interactive aspect of the model tends to result in similar behavior when different levels of the model are lesioned. Another line of evidence suggests that the flow of information from lower to higher levels is reduced rather than blocked. Many pure alexic patients are able to perform lexical decisions or even semantic categorizations (animal versus object) for briefly presented words that they cannot read (Bowers et al., 1996; Shallice & Saffran, 1986). For this to occur, one needs to assume that there is some partial parallel processing of the letter string that is able to access meaning and lexical representations, but that is insufficient to permit conscious visual word recognition (Roberts et al., 2010).

In pure alexia (or letter-by-letter reading), reading time is slow and laborious and is strongly affected by word length (see graph on the left). Patients often have difficulty in determining whether two letters are the same when they differ by case (e.g. slow at judging that A–a have the same identity, but not at judging that A–a are physically different; see graph on the right). The disorder results in a difficulty in parallel processing of abstract letter identities, but it is still debated whether the primary deficit is visual or reading-specific.

Key Terms

Fixation

A stationary pause between eye movements.

Evaluation

There is good evidence that there is a region within the mid-fusiform cortex that responds relatively more to word and word-like stimuli than other kinds of visual object. Although located within the “visual” ventral stream, neither its precise function nor anatomical location are strictly visual. Instead it is a region that connects vision to the wider language network and also multi-modal shape processing. Whether the region stores known words (i.e. implements a visual lexicon) in addi tion to letter patterns remains a matter of debate as the presence of word-specific effects could be related to top-down effects (e.g. from the semantic system) rather than reflecting a store of word forms.

What do Studies of Eye Movement Reveal About Reading Text?

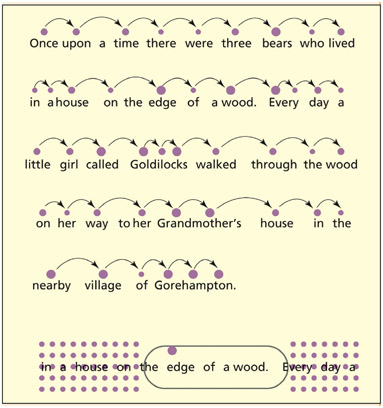

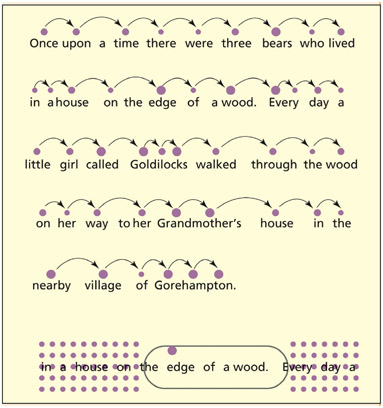

Eye movement is required when reading text, because visual acuity is greatest at the fovea and words in the periphery are hard to recognize quickly and accurately. However, the control of eye movements in reading clearly has two masters: visual perception and text comprehension (Rayner & Juhasz, 2004; Rayner, 2009). The eyes move across the page in a series of jerks (called saccades) and pauses (called fixations). This stands in contrast to following a moving target, in which the eyes move smoothly. To understand this process in more detail, we can break it down into two questions: How do we decide where to land during a saccade? How do we decide when to move after a fixation?

First, reading direction affects both the movement of saccades and the extraction of information during fixation. English speakers typically have left-to-right reading saccades and absorb more information from the right of fixation. It is more efficient to consider upcoming words than linger on previously processed ones. The eyes typically fixate on a point between the beginning and middle of a word (Rayner, 1979), and take information concerning three or four letters on the left and 15 letters to the right (Rayner et al., 1980). Hebrew readers do the opposite (Pollatsek et al., 1981).

The landing position within a word may be related to perceptual rather than linguistic factors. The predictability of a word in context does not influence landing position within the word (Rayner et al., 2001), nor does morphological complexity (Radach et al., 2004). Whether or not a word is skipped altogether seems to depend on how short it is (a perceptual factor) (Rayner & McConkie, 1976) and how predictable it is (a linguistic factor) (Rayner et al., 2001). The frequency of a word and its predictability do influence the length of time fixated (Rayner & Duffy, 1986). Similarly, the length of time fixated seems to depend on morphological complexity (Niswander et al., 2000).

Top: not all words get fixated during reading and the duration of fixation varies from word to word (shown by the size of the dot). Bottom: in left-to-right readers, information is predominantly obtained from the right of fixation.

Several detailed models have been developed that attempt to explain this pattern of data (in addition to making new testable predictions) that take into account the interaction of perceptual and linguistic factors (Pollatsek et al., 2006; Reilly & Radach, 2006).

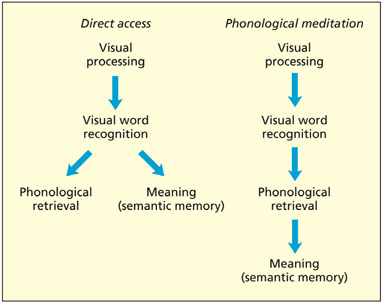

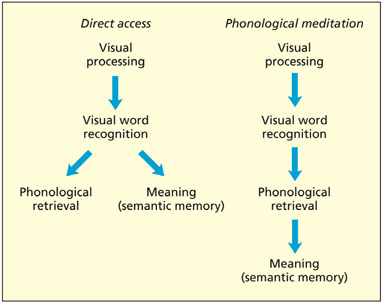

Do we need to access the spoken forms of words in order to understand them? In the model on the left, phonological retrieval may accompany silent reading but is not essential for it. In the model on the right, phonological mediation is essential for comprehension of text.

There are, broadly speaking, two things that one may wish to do with a written word: understand it (i.e. retrieve its meaning from semantic memory) or say it aloud (i.e. convert it to speech). Are these two functions largely separate or is one dependent on the other? For instance, does understanding a written word require that it first be translated to speech (i.e. a serial architecture)? This possibility has sometimes been termed phonological medi ation. The alternative proposal is that under standing written words and transcoding text into speech are two largely separate, but interacting, parallel processes. The evidence largely supports the latter view and has given rise to so-called dual route architectures for reading, which are discussed in this section.

Key Terms

Phonological mediation

The claim that accessing the spoken forms of words is an obligatory component of understanding visually presented words.

Homophone

Words that sound the same but have different meanings (and often different spellings), e.g. ROWS and ROSE.

Many studies that have examined the inter action between word meaning and phonology have used as stimuli homophones (words with the same phonology but different spelling, e.g. ROWS and ROSE) or pseudo-homophones (nonwords that are pronounced like a real word; e.g. BRANE). Van Orden (1987; Van Orden et al., 1988) reported that normal participants are error-prone when making semantic categorizations when a stimulus is homophonic with a true category member (e.g. determining whether ROWS is a FLOWER). This was taken as evidence that mapping between visual words and their meaning requires phonological mediation (i.e. that understanding text depends on first accessing the spoken form of a word). This evidence certainly speaks against the alternative view of two separate and noninteracting processes. However, it is consistent with the notion of separate but interacting routes. For instance, some acquired aphasic patients who make phonemic errors during reading, naming, and spontaneous speech are capable of understanding the meaning of written homophones even if they have no idea whether the words ROWS and ROSE would sound the same if read loud (Hanley & MacDonell, 1997). This suggests intact access from text-to-meaning together with impaired access from text-to-speech.

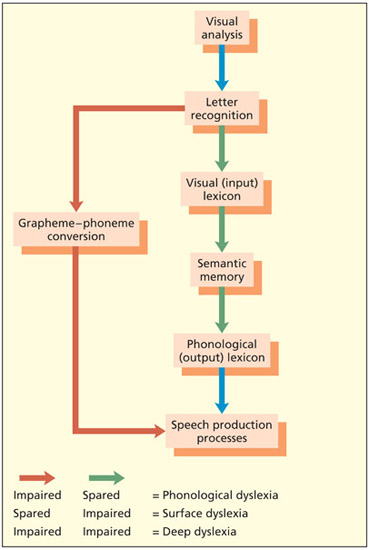

The most influential models of reading aloud are based on a dual-route model of reading initially put forward by Marshall and Newcombe (1973). The key features of this model are: (1) a semantically based reading route in which visual words are able to access semantics directly; and (2) a phonologically based reading route that uses known regularities between spelling patterns and phonological patterns (e.g. the letters TH are normally pronounced as “th”) to achieve reading. This route is also called grapheme–phoneme conversion.

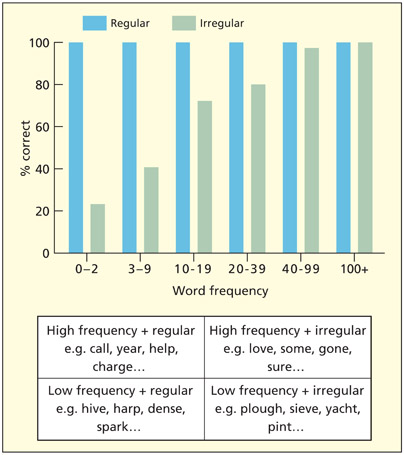

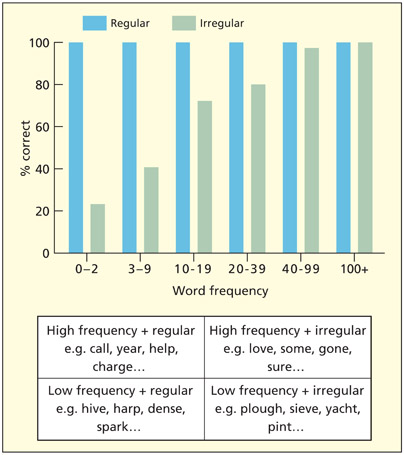

Before going on to consider later developments of the model, it is important to state the key properties of the standard, traditional dual-route model (Morton, 1980; Patterson, 1981; Shallice et al., 1983). In the traditional model, the phonologically based route is considered to instantiate a procedure called grapheme– phoneme conversion, in which letter patterns are mapped onto corresponding phonemes. This may be essential for reading nonwords, which, by definition, do not have meaning or a stored lexical representation. Known words, by contrast, do have a meaning and can be read via direct access to the semantic system and thence via the stored spoken forms of words. Of course, many of these words could also be read via grapheme–phoneme conversion, although in the case of words with irregular spellings it would result in error (e.g. YACHT read as “yatched”). The extent to which each route is used may also be determined by speed of processing—the direct semantic access route is generally considered faster. This is because it processes whole words, whereas the grapheme–phoneme conversion route processes them bit-by-bit. The semantic route is also sensitive to how common a word is—known as word frequency (and not to be confused with “frequency” in the auditory sense). Reading time data from skilled adult readers is broadly consistent with this framework. High-frequency words (i.e. those that are common in the language) are fast to read, irrespective of the sound–spelling regularity. For low-frequency words, regular words are read faster than irregular ones (Seidenberg et al., 1984).

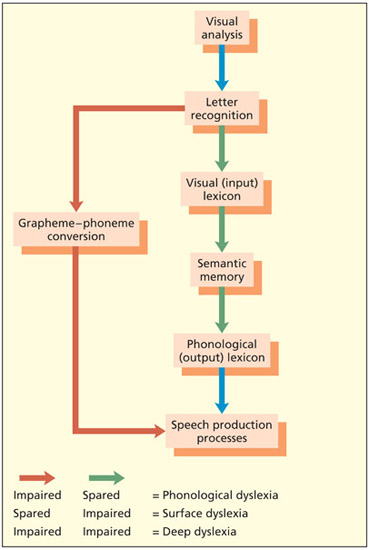

Profiles of acquired central dyslexias

The dual-route model predicts that selective damage to different components comprising the two routes should have different consequences for the reading of different types of written material. Indeed this appears to be so. Some patients are able to read nonwords and regularly spelled words better than irregularly spelled words, which they tend to pronounce as if they were regular (e.g. DOVE pronounced “doove” like “move,” and CHAOS pronounced with a “ch” as in “church”). These patients are called surface dyslexics (Patterson et al., 1985; Shallice et al., 1983). Within the dual-route system it may reflect reliance on grapheme–phoneme conversion arising from damage to the semantic system (Graham et al., 1994) or visual lexicon itself (Coltheart & Funnell, 1987). In the figure below, they use the red route for reading, which enables nonwords and regularly spelled words to be read accurately. The green route may still have some level of functioning that supports high-frequency words. As such, these patients typically show a frequency · regularity interaction. That is, high-frequency words tend to be read accurately no matter how regular they are, but low frequency words tend to be particularly error prone when they are irregular (see figure on p. 306).

Key Terms

Surface dyslexia

Ability to read nonwords and regularly spelled words better than irregularly spelled words.

Phonological dyslexia

Ability to read real words better than nonwords.

Deep dyslexia

Real words are read better than nonwords, and semantic errors are made in reading.

Another type of acquired dyslexia has been termed phonological dyslexia. These patients are able to read real words better than nonwords, although it is to be noted that real word reading is not necessarily 100 percent correct (Beauvois & Derouesne, 1979). When given a nonword to read, they often produce a real word answer (e.g. CHURSE read as “nurse”), and more detailed testing typically reveals that they have problems in aspects of phonological processing (e.g. auditory rhyme judgment) but that they can perceive the written word accurately (Farah et al., 1996; Patterson & Marcel, 1992). As such, these patients are considered to have difficulties in the phonological route (grapheme–phoneme conver sion) and are reliant on the lexical–semantic route. In the figure on the right they rely on green route for reading and have limited use of the red route.

A dual-route model of reading. The standard lexical–semantic and grapheme–phoneme conversion routes are shown in green and red respectively. Grapheme-phoneme conversion is a slower route that can accurately read nonwords and regularly spelled words. The lexical–semantic route is faster and can read all known words (whether regular or irregularly spelled) but is more efficient for common, high-frequency words.

Another type of acquired dyslexia exists that resembles phonological dyslexia in that real words are read better than nonwords, but in which real word reading is more error-prone and results in a particularly intriguing type of error—a semantic error (e.g. reading CAT as “dog”). This is termed deep dyslexia (Coltheart et al., 1980). The patients also have a number of other characteristics, including a difficulty in reading low imageability (e.g. truth) relative to high imageability (e.g. wine) words. Within the original dual-route model, this was explained as damage to grapheme–phoneme conversion and use of the intact semantic pathway (Marshall & Newcombe, 1973). However, this explanation is clearly inadequate, because it predicts that the semantic route is normally very error-prone in us all, and it fails to predict that patients with deep dyslexia have comprehension problems on tests of semantic memory that do not involve written material (Shallice, 1988). The most common way of ex-plaining deep dyslexia is to assume that both reading routes are impaired (Nolan & Caramazza, 1982). The lexical–semantic route is degraded such that similar concepts have effectively become fused together and cannot be distinguished from one another, and the absence of grapheme-phoneme conversion prevents an alternative means of output.

Frequency → regularity interaction in the word reading of a semantic dementia patient and examples of words falling into these categories.

Reprinted from Ward et al., 2000. © 2000, with permission from Elsevier.

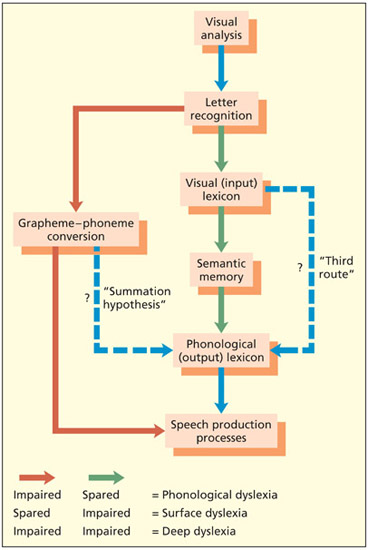

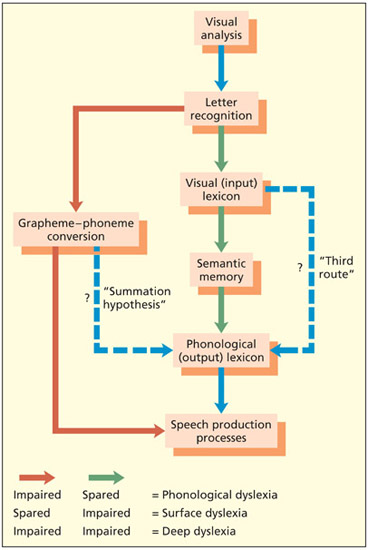

A number of studies have reported patients who can read words aloud accurately but have impaired nonword reading and impaired semantic knowledge (Cipolotti & Warrington, 1995b; Coslett, 1991; Funnell, 1983; Lambon Ralph et al., 1995). So how are these patients able to read? The problem with nonwords implies a difficulty in grapheme–phoneme conversion, and the problem in comprehension and semantic memory implies a difficulty in the lexical–semantic route. One might predict the patients would be severely dyslexic—probably deep dyslexic. To accommodate these data, several researchers have argued in favor of a “third route” that links the visual lexicon with the phonological lexicon but does not go through semantics (Cipolotti & Warrington, 1995b; Coltheart et al., 1993; Coslett, 1991; Funnell, 1983).

There are several alternative accounts to the “third route” that have been put forward to explain good word reading in the face of impaired semantic knowledge. Woollams et al. (2007) noted that these cases, when observed in the context of semantic dementia, do tend to go on to develop word-reading problems (particularly for irregular spellings) as their semantic memory gets worse. They suggest that an intact semantic system is always needed for reading these words, but people differ in the extent to which they rely on one route more than the other. Those who rely more on the semantic route before brain damage will show the largest disruption in reading ability when they go on to develop semantic dementia. An alternative to the third route is provided by the summation hypothesis (Hillis & Caramazza, 1991; Ciaghi et al., 2010). The summation hypothesis states that lexical representations in reading are selected by summing the activation from the semantic system and from grapheme–phoneme conversion. Thus patients with partial damage to one or both of these routes may still be able to achieve relatively proficient performance at reading, even with irregular words. For example, in trying to read the irregular word bear, a degraded semantic system may activate a number of candidates including bear, horse, cow, etc. However, the grapheme–phoneme conversion system will also activate, to differing, a set of lexical candidates that are phonologically similar (“beer,” “bare,” “bar,” etc.). By combining these two sources of information, the patient should be able to arrive at the correct pronunciation of “bear,” even though neither route may be able to select the correct entry by itself. This prediction was tested by Hillis and Caramazza (1991). Their surface dyslexic/dysgraphic participant was able to read and spell irregular words for which he had partial understanding (e.g. superordinate category) but not irregular words for which no understanding was demonstrated.

An adapted dual-route model of reading showing two alternative modifications to the model (blue lines). These modifications have been proposed by some researchers to account for the fact that some acquired dyslexic patients can read irregular words that they cannot understand. They bypass semantic memory.

What has functional imaging revealed about the existence of multiple routes?

The initial motivation for postulating two (or more) routes for reading was cognitive, not neuroanatomical. Nevertheless, functional imaging may provide an important source of converging evidence to this debate—at least in principle (for reviews, see Fiez & Petersen, 1998; Jobard et al., 2003; Cattinelli et al., 2013). Of course, functional imaging measures the activity of regions only in response to particular task demands, and so it does not provide any direct evidence for actual anatomical routes between brain regions.

Aside from the mid-fusiform (or VWFA) region already considered, a number of other predominantly left-lateralized regions are con sistently implicated in fMRI studies of reading and reading-related processes such as lexical decision. These include the inferior frontal cortex (including Broca’s area); the inferior parietal lobe; and several anterior and mid-temporal lobe regions. These are considered in turn.

Inferior frontal lobe (Broca’s area)

This region is implicated in fMRI studies of reading, as well as in language processing in general (see Chapter 11). Some have suggested that the inferior frontal lobe does not have a core role to play in single-word reading, but is instead related to general task difficulty (Cattinelli et al., 2013). However, others have suggested that it has a specific role in converting graphemes to phonemes (Fiebach et al., 2002). This is because this region is activated more by low frequency words with an irregular spelling (Fiez et al., 1999). These words are the hardest to read via that system, and the assumption is that more cognitive effort manifests itself as greater BOLD activity. An alternative way of interpreting in creased activity for low frequency irregular words is by assuming that a greater BOLD response for these items provides evidence for more semantic support being offered by this region (rather than reflecting the grapheme–phoneme conversion routine working harder). Indeed, some studies have made this alternative claim (Jobard et al., 2003). It is possible that both claims could be true if different sub-regions were contributing to both reading routes. Heim et al. (2005) suggest that BA45 is involved in semantic retrieval (e.g. during lexical decision), but BA44 supports grapheme–phoneme conversion. Patients with damage to the wider inferior frontal region make more errors on nonwords than real regular words, but additionally struggle with low-frequency irregular words (Fiez et al., 2006). That is, the pattern is neither a specific profile of surface dyslexia or of phonological dyslexia but a mix of the two. This suggests that the region does indeed serve multiple functions during reading rather than being specifically tied to one process/route.

Key areas identified in brain imaging studies and their possible functions. Note that the anatomical routes (and intermediate processing stages) are largely unknown and are shown here as illustrative possibilities. The role of the inferior frontal lobe (Broca’s area) in reading is uncertain but may contribute to both semantically based reading and reading via phonological decoding. It may also bias the reading strategy that is adopted (according to the task).

Inferior parietal lobe

The inferior parietal lobe consists of two anatomical regions: the supramarginal gyrus, which abuts the superior temporal lobes; and the angular gyrus, lying more posteriorly. Both have long been linked to language. The supramarginal gyrus was historically linked to Wernicke’s area (and phonological processing in particular). The angular gyrus has been linked to verbal working memory (Paulesu et al., 1993) and binding semantic concepts (Binder & Desai, 2011). With particular reference to reading, it has been suggested that the left supramarginal gyrus is implicated in grapheme–phoneme conversion. It tends to be activated more by nonwords than words, and evidence from intracranial EEG (Juphard et al., 2011) and fMRI (Church et al., 2011) suggest that reading of longer nonwords is linked to longer duration of EEG activity and increased BOLD signal. These findings suggest piecemeal processing of letter string rather than holistic recognition. An excitatory (rather than inhibitory) version of TMS over this region facilitates nonword reading (Costanzo et al., 2012), whereas inhibitory TMS impairs phonological (but not semantic) judgments about written words (Sliwinska et al., 2012). Finally, patients with semantic dementia hyper-activate this region, relative to controls, when attempting to read low frequency irregular words (Wilson et al., 2012). These words tend to be regularized by these patients (e.g. SEW read as “sue”) suggesting that they, but not controls, may utilize this region to read these words (i.e. to compensate for their inability to read the words using semantics).

Anterior and mid-temporal lobe

These regions of the brain are strongly implicated in supporting semantic memory. Within models of reading, one would therefore expect that they would contribute to the reading-via-meaning route (i.e. mapping orthography to phonology via semantics). The mid-temporal cortex is a region that tends to be activated, during fMRI, in semantic relative to phonological processing of written words (Mechelli et al., 2007). Gray matter volume in this region, and the anterior temporal pole, measured by VBM correlates with ability in reading of irregular words in aphasic patients (Brambati et al., 2009). Finally, patients with semantic dementia, who invariably present with surface dyslexia, have lesions in this area (Wilson et al., 2009).

In summary, the evidence from functional imaging suggests that different brain regions are involved in reading via grapheme–phoneme conversion (left supramarginal gyrus) and reading via meaning (anterior and mid-temporal lobes). This evidence generally supports the dual-route notion but does not—at present— discriminate well between different versions of it. Other regions (e.g. left inferior frontal lobe) have an important role in reading but serve an unclear function, as they do not clearly map onto a construct within current cognitive models of reading.

Is the same reading system universal across languages?

The dual-route model is an attractive framework for understanding reading in opaque languages such as English, in which there is a mix of regular and irregular spelling-to-sound patterns. But to what extent is this model likely to extend to languages with highly transparent mappings (e.g. Italian) or, at the other extreme, are logographic rather than alphabetic (e.g. Chinese)? The evidence suggests that the same reading system is indeed used across other languages, but the different routes and components may be weighted differently according to the culture-specific demands.

Functional imaging suggests that reading uses similar brain regions across different languages, albeit to varying degrees. Italian speakers appear to activate more strongly areas involved in phonemic processing when reading words, whereas English speakers activate more strongly regions implicated in lexical retrieval (Paulesu et al., 2000). Studies of Chinese speakers also support a common network for reading Chinese logographs and reading Roman-alphabetic transcriptions of Chinese (the latter being a system, called pinyin, used to help in teaching Chinese; Chen et al., 2002). Moreover, Chinese logographs resemble English words more than they do pictures in terms of the brain activity that is engendered, although reading Chinese logographs may make more demands on brain regions involved in semantics than reading English (Chee et al., 2000). The latter is supported by cognitive studies showing that reading logographs is more affected by word imageability than reading English words (Shibahara et al., 2003). Imageability refers to whether a concept is concrete or abstract, with concrete words believed to possess richer semantic representations. Thus, it appears that Chinese readers may be more reliant on reading via semantics but that the reading system is co-extensive with that used for other scripts.

Cases of surface dyslexia have been documented in Japanese (Fushimi et al., 2003) and Chinese (Weekes & Chen, 1999). Reading of Chinese logographs and Japanese Kanji can be influenced by the parts that comprise them. These parts have different pronunciations in different contexts, with degree of consistency varying. This is broadly analogous to grapheme–phoneme regularities in alphabetic scripts. Indeed, the degree of consistency of character–sound correspondence affecting reading of both words and nonwords is particularly apparent for low-frequency words. The results suggest that there are nonsemantic routes for linking print with sound even in scripts that are not based on the alphabetic principle. Conversely, phonological dyslexia has been observed in these scripts, adding further weight to the notion that the dual-route model may be universal (Patterson et al., 1996; Yin & Weekes, 2003). Similarly, surface dyslexia (Job et al., 1983) and phonological dyslexia (De Bastiani et al., 1988) have been observed in Italian, even though this reading system is entirely regular and could, in principle, be achieved by grapheme– phoneme correspond ence alone. As with English and Chinese, Italian also shows a word frequency · regularity inter action for reading aloud in skilled adult readers (Burani et al., 2006).

Although Chinese is not alphabetic, whole words and characters can nevertheless be decomposed into a collection of parts. There is evidence to suggest that there is a separate route that is sensitive to part-based reading of Chinese characters that is analogous to grapheme–phoneme conversion in alphabetic scripts.

Evaluation

The dual-route model of reading presently remains the most viable model of reading aloud. It is able to account for skilled reading, for patterns of acquired dyslexia, and for difference in regional activity observed in functional imaging when processing different types of written stimuli. The model also extends to written languages that are very different from English. However, the precise nature of the computations carried out still remains to be fully elucidated.

Spelling has received less attention than the study of reading. For example, there is a paucity of functional imaging studies dedicated to the topic (but see Beeson et al., 2003). The reasons for this are unclear. Producing written language may be less common as a task for many people than reading; it may also be harder. For example, many adult developmental dyslexics can get by adequately at reading but only manifest their true difficulties when it comes to spelling (Frith, 1985). However, the study of spelling and its disorders has produced some intriguing insights into the organization of the cognitive system dedicated to literacy.

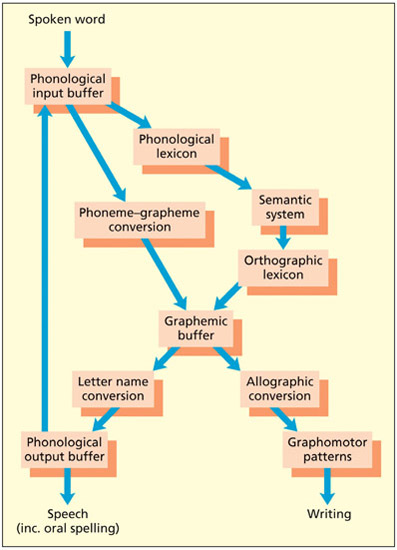

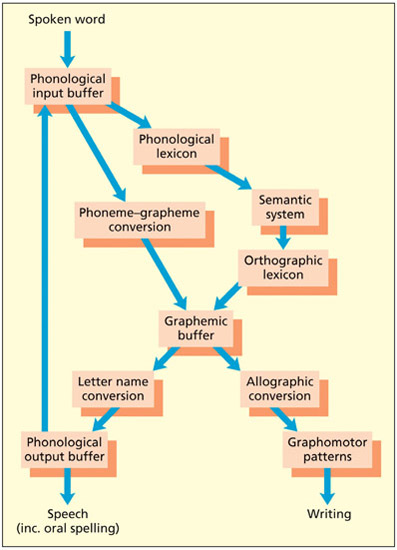

A model of spelling and writing

First, it is important to make a distinction between the process of selecting and retrieving a letter string to be produced, and the task of physically producing an output. The latter task may take various forms such as writing, typing, and oral spelling. The term “spelling” can be viewed as an encompassing term that is neutral with respect to the mode of output.

Key Terms

Dysgraphia

Difficulties in spelling and writing.

Graphemic buffer

A short-term memory component that maintains a string of abstract letter identities while output processes (for writing, typing, etc.) are engaged.

As with reading, dual-route models of spelling have been postulated (for a review, see Houghton & Zorzi, 2003). In spelling the task demands are reversed, in that one is attempting to get from a spoken word or a concept to an orthographic one. As such, the names of some of the components are changed to reflect this. For example, phoneme–grapheme conversion is a hypothesized component of spelling, whereas grapheme–phoneme conversion is the reading equivalent.

The principal line of evidence for this model comes from the acquired dysgraphias. In surface dysgraphia, patients are better at spelling to dictation regularly spelled words and nonwords, and are poor with irregularly spelled words (e.g. “yacht” spelled as YOT) (Beauvois & Derouesne, 1981; Goodman & Caramazza, 1986a). This is considered to be due to damage to the lexical–semantic route and reliance on phoneme–grapheme conversion. Indeed, these cases typically have poor comprehension characteristic of a semantic disorder (Graham et al., 2000). In contrast, patients with phonological dysgraphia are able to spell real words better than nonwords (Shallice, 1981). This has been explained as a difficulty in phoneme–grapheme conversion, or a problem in phono logical segmentation itself. Deep dysgraphia (e.g. spelling “cat” as D-O-G) has been reported too (Bub & Kertesz, 1982). As with reading, there is debate concerning whether there is a “third route” that directly connects phono logical and ortho graphic lexicons that by-passes semantics (Hall & Riddoch, 1997; Hillis & Caramazza, 1991). It is important to note that all of these spelling dis orders are generally independent of the modality of output. For example, a surface dysgraphic patient would tend to produce the same kinds of errors in writing, typing, or oral spelling.

A dual-route model of spelling.

The graphemic buffer

The graphemic buffer is a short-term memory component that holds on to the string of abstract letter identities while output processes (for writing, typing, etc.) are engaged (Wing & Baddeley, 1980). As with other short-term memory systems, the graphemic buffer may be mediated by particular frontoparietal networks (Cloutman et al., 2009). The term “grapheme” is used in this context to refer to letter identities that are not specified in terms of case (e.g. B versus b), font (b versus b), or modality of output (e.g. oral spelling versus writing). Another important feature of the graphemic buffer is that it serves as the confluence of the phoneme–grapheme route and the lexical– semantic spelling route. As such, the graphemic buffer is used in spelling both words and nonwords.

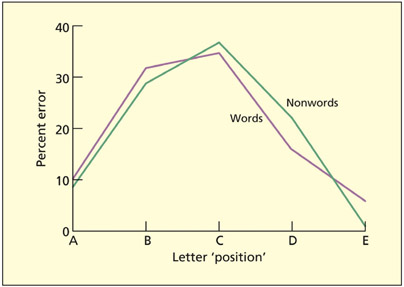

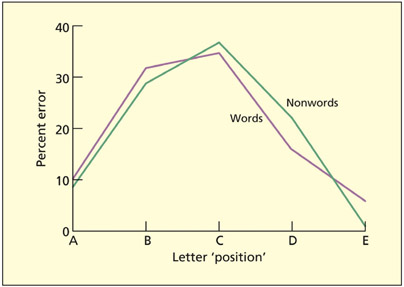

Patient LB had graphemic buffer damage and produced spelling errors with both words and nonwords. The errors tended to cluster around the middle of the word.

Wing and Baddeley (1980) analyzed a large corpus of spelling errors generated by candidates sitting an entrance exam for Cambridge University. They considered letter-based errors that were believed to reflect output errors (“slips of the pen”) rather than errors based on lack of knowledge of the true spelling (e.g. the candidate had correctly spelled the word on another occa sion). These errors consisted of letter trans positions (e.g. HOSRE for HORSE), substitutions (e.g. HOPSE for HORSE), omissions (e.g. HOSE for HORSE), and additions (HORESE for HORSE). These errors were assumed to arise from noise or inter ference between letters in the graphemic buffer. One additional characteristic of these errors is that they tended to cluster in the middle of words, giving an inverted U-shaped error distribution. Wing and Baddeley speculated that letters in the middle have more neighbors and are thus susceptible to more interference.

The most detailed example of acquired damage to the graphemic buffer is patient LB (Caramazza et al., 1987; Caramazza & Miceli, 1990; Caramazza et al., 1996). In some respects, the errors could be viewed as a pathological extreme of those documented by Wing and Baddeley (1980). For example, spelling mistakes consisted of single-letter errors and were concentrated in the middle of words. In addition, equivalent spelling errors were found irrespective of whether the stimulus was a word or nonword, and irrespective of output modality. This is consistent with the central position of the graphemic buffer in the cognitive architecture of spelling. In addition, word length had a significant effect on the probability of an error. This is consistent with its role as a limited capacity retention system.

There is evidence to suggest that the information held in the graphemic buffer consists of more than just a linear string of letter identities (Caramazza & Miceli, 1990). In particular, it has been argued that consecutive double letters (e.g. the BB in RABBIT) have a special status. Double letters (also called geminates) tend to be misspelled such that the doubling information migrates to another letter (Tainturier & Caramazza, 1996). For example, RABBIT may be spelled as RABITT. However, errors such as RABIBT are conspicuously absent, even though they exist for comparable words that lack a double letter (e.g. spelling BASKET as BASEKT). This suggests that our mental representation of the spelling of the word RABBIT does not consist of R-A-B-B-I-T but consists of R-A-B[D]-I-T, where [D] denotes that the letter should be doubled. Why do double letters need this special status? One suggestion is that, after each letter is produced, it gets inhibited to prevent it getting produced again and to allow another letter to be processed (Shallice et al., 1995). When the same letter needs to be written twice in a row, a special mechanism is required to block this inhibition.

Output processes in writing and oral spelling

There is evidence for separate written versus oral letter name output codes in spelling. Some patients have damage to the letter names that selectively impairs oral spelling relative to written spelling (Cipolotti & Warrington, 1996; Kinsbourne & Warrington, 1965). The task of oral spelling is likely to be closely linked with other aspects of phonological processing (for a review, see Ward, 2003). In contrast, some patients are better at oral spelling than written spelling (Goodman & Caramazza, 1986b; Rapp & Caramazza, 1997). These peripheral dysgraphias take several forms and are related to different stages, from specification of the abstract letter to production of pen strokes.

Key Terms

Allograph

Letters that are specified for shape (e.g. case, print versus script).

Graph

Letters that are specified in terms of stroke order, size and direction.

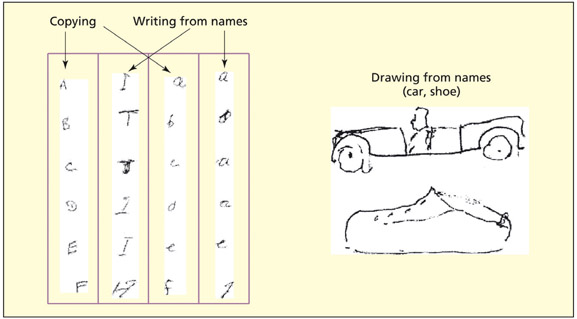

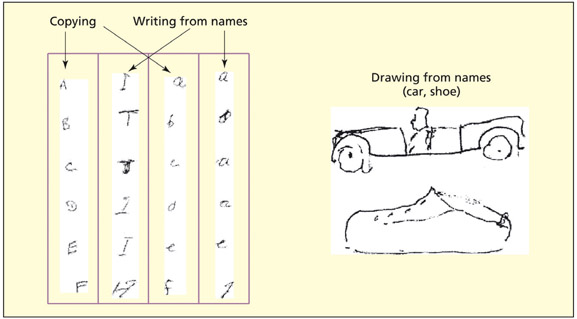

Ellis (1979, 1982) refers to three different levels of description for a letter. The grapheme is the most abstract description that specifies letter identity, whereas an allograph refers to letters that are specified for shape (e.g. case, print versus script), but not motor output, and the graph refers to a specification of stroke order, size and direction. Damage to the latter two stages would selectively affect writing over oral spelling. Patients with damage to the allographic level may write in mIxeD CaSe, and have selective difficulties with either lowercase writing (Patterson & Wing, 1989) or upper-case writing (Del Grosso et al., 2000). They also tend to substitute a letter for one of similar appearance (Rapp & Caramazza, 1997). Although this could be taken as evidence for confusions based on visual shape, it is also the case that similar shapes have similar graphomotor demands. Some researchers have argued that allographs are simply pointers that denote case and style but do not specify the visual shape of the letter (Del Grosso Destreri et al., 2000; Rapp & Caramazza, 1997). Rapp and Caramazza (1997) showed that their patient, with hypothesized damage to allographs, was influenced by graphomotor similarity and not shape when these were independently controlled for. Other dysgraphic patients can write letters far better than they can visually imagine them (Del Grosso Destreri et al., 2000) or can write words from dictation but cannot copy the same words from a visual template (Cipolotti & Denes, 1989). This suggests that the output codes in writing are primarily motoric rather than visuospatial.

Patient IDT was unable to write letters to dictation, but could draw pictures on command and copy letters. This ability rules out a general apraxic difficulty.

The motor representations for writing themselves may be damaged (“graphs” in the terminology above). Some patients can no longer write letters but can draw,

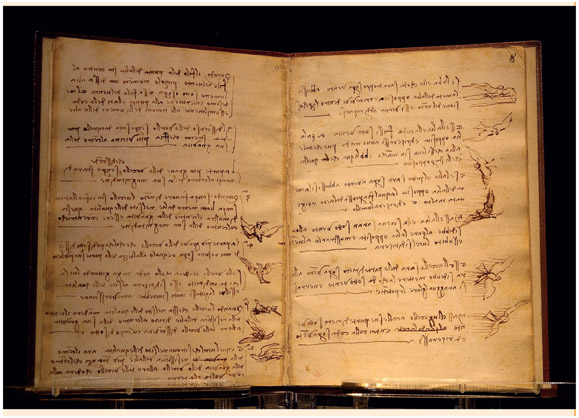

The Unusual Spelling and Writing of Leonardo Da Vinci

Was Leonardo da Vinci surface dysgraphic? Why did he write mirror-distorted letters from right to left? An example of this is shown here in his Codex on the Flight of Birds? (circa 1505).

The writing of Leonardo da Vinci is unusual in terms of both content and style. In terms of content, there are many spelling errors. This suggests that he may have been surface dyslexic/ dysgraphic (Sartori, 1987). In terms of style, his handwriting is highly idiosyncratic and is virtually unreadable except to scholars who are familiar with his style. Da Vinci wrote in mirror-reversed script, such that his writing begins on the right side of the page and moves leftward. The letters themselves were mirror-image distortions of their conventional form. This has been variously interpreted as a deliberate attempt at code (to retain intellectual ownership over his ideas), as proof that he was no mere mortal (for either good or evil) or as being related to his left-handedness. It is well documented that da Vinci was a left-hander and a small proportion of left-handed children do spontaneously adopt such a style. An alternative is that he was born right-handed but sustained an injury that forced him to write with his left hand. Natural right-handers are surprised at how easy it is to write simultaneously with both hands, with the right hand writing normally and the left hand mirror-reversed (for discussion, see McManus, 2002).

As for his spelling errors, Sartori (1987) argues that da Vinci may have been surface dysgraphic. The cardinal feature of this disorder is the spelling of irregular words in a phonetically regular form. Although Italian (da Vinci’s native language) lacks irregular words, it is nevertheless possible to render the same phonology in different written forms. For example, laradio and l’aradio are phonetically plausible, but conventionally incorrect, renditions of la radio (the radio). This type of error was commonplace in da Vinci’s writings, as it is in modern-day Italian surface dysgraphics (Job et al., 1983). It is, however, conspicuously absent in the spelling errors of normal Italian controls.

copy and even write numbers, which suggests that the difficulty is in stored motor representations and not action more generally (Baxter & Warrington, 1986; Zettin et al., 1995).

Patient VB is described as having “afferent dysgraphia,” which is hypothesized to arise from a failure to utilize visual and motor feedback during the execution of motor tasks, such as writing. Similar errors are observed in normal participants when feedback is disrupted by blindfolding and when producing an irrelevant motor response.

Although the stored codes for writing may be motoric rather than visual, vision still has an import ant role to play in guiding the online execution of writing. Patients with afferent dysgraphia make many stroke omissions and additions in writing (Cubelli & Lupi, 1999; Ellis et al., 1987). Interestingly, similar error patterns are found when healthy individuals write blindfolded and have distracting motor activity (e.g. tapping with their non-writing hand) (Ellis et al., 1987). It suggests that these dysgraphic patients are unable to utilize sensorimotor feedback even though basic sensation (e.g. vision, proprioception) is largely unimpaired.

Given the inherent similarities between reading and spelling, one may wonder to what extent they share the same cognitive and neural resources. Many earlier models postulated the existence of separate lexicons for reading and spelling (Morton, 1980). However, the evidence in favor of this separation is weak. In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that the same lexicon may support both reading and spelling (Behrmann & Bub, 1992; Coltheart & Funnell, 1987). Both of these studies reported patients with surface dyslexia and surface dysgraphia who showed item-for-item consistency in the words that could and could not be read or spelled. These studies concluded that this reflects loss of word forms from a lexicon shared between reading and spelling.

Key Term

Afferent dysgraphia

Stroke omissions and additions in writing that may be due to poor use of visual and kinesthetic feedback.

There is also some evidence to suggest that the same graphemic buffer is employed both in reading and spelling (Caramazza et al., 1996; Tainturier & Rapp, 2003). However, graphemic buffer damage may have more dire consequences for spelling than reading, because spelling is a slow process that makes more demands on this temporary memory structure than reading. In reading, letters may be mapped on to words in parallel and loss of information at the single-letter level may be partially compensated for. For example, reading EL??HANT may result in correct retrieval of “elephant” despite loss of letter information (where the question marks represent degraded information in the buffer). However, attempting to spell from such a degraded representation would result in error. Patients with graphemic buffer damage are particularly bad at reading nonwords, because this requires analysis of all letters, in contrast to reading words in which partial information can be compensated for to some extent (Caramazza et al., 1996). Moreover, their errors show essentially the same pattern in reading and spelling, including a concentration at the middle of words. This suggests that the same graphemic buffer participates in both reading and spelling.

Functional imaging studies of writing activate a region of the left fusiform that is the same as the so-called visual word form area implicated in reading. For example, this region is active when writing English words from a category examplar relative to drawing circles (Beeson et al., 2003), and when writing Japanese Kanji characters (Nakamura et al., 2000). Brain-damaged patients with lesions in this region are impaired at both spelling and reading for both words and nonwords (Philipose et al., 2007). The functional interpretation of this region is controversial (see above) and may reflect a single lexicon for reading and spelling, a common graphemic buffer, or possibly a multi-modal language region. In each case, it appears that reading and spelling have something in common in terms of anatomy.

Evaluation

Not only is the functional architecture of spelling very similar to that used for reading, there is also evidence to suggest that some of the cognitive components (and neural regions) are shared between the task. There is evidence to suggest sharing of the visual/orthographic lexicon and of the graphemic buffer. However, the evidence suggests that the representation of letters used in writing is primarily graphomotor and that this differs from the more visuospatial codes that support both reading and imagery of letters.