FLIPSIDE INTERVIEWER: DO YOU MAKE A PROFIT?

GREG GINN: WE TRY TO EAT.

It’s not surprising that the indie movement largely started in Southern California—after all, it had the infrastructure: Slash and Flipside fanzines started in 1977, and indie labels like Frontier and Posh Boy and Dangerhouse started soon afterward. KROQ DJ Rodney Bingenheimer played the region’s punk music on his show; listeners could buy what they heard thanks to various area distributors and record shops and see the bands at places like the Masque, the Starwood, the Whisky, the Fleetwood, and various impromptu venues. And there were great bands like the Germs, Fear, the Dickies, the Dils, X, and countless others. No other region in the country had quite as good a setup.

But by 1979 the original punk scene had almost completely died out. Hipsters had moved on to arty post-punk bands like the Fall, Gang of Four, and Joy Division. They were replaced by a bunch of toughs coming in from outlying suburbs who were only beginning to discover punk’s speed, power, and aggression. They didn’t care that punk rock was already being dismissed as a spent force, kid bands playing at being the Ramones a few years too late. Dispensing with all pretension, these kids boiled the music down to its essence, then revved up the tempos to the speed of a pencil impatiently tapping on a school desk, and called the result “hardcore.” As writer Barney Hoskyns put it, this new music was “younger, faster and angrier, full of the pent-up rage of dysfunctional Orange County adolescents who’d had enough of living in a bland Republican paradise.”

Fairly quickly, hardcore spread around the country and coalesced into a small but robust community. Just as “hip-hop” was an umbrella term for the music, art, fashion, and dance of a then nascent urban subculture, so was “hardcore.” Hardcore artwork was all stark, cartoonish imagery, rough-hewn photocopied collage, and violently scrawled lettering; fashion was basically typical suburban attire but ripped and dingy, topped with militarily short haircuts; the preferred mode of terpsichorean expression was a new thing called slam dancing, in which participants simply bashed into one another like human bumper cars.

Hardcore punk drew a line in the sand between older avant-rock fans and a new bunch of kids who were coming up. On one side were those who considered the music (and its fans) loud, ugly, and incoherent; to the folks on the other side, hardcore was the only music that mattered. A rare generational divide in rock music had arisen. And that’s when exciting things happen.

Black Flag was more than just the flagship band of the Southern California hardcore scene. It was more than even the flagship band of American hardcore itself. They were required listening for anyone who was interested in underground music. And by virtue of their relentless touring, the band did more than any other to blaze a trail through America that all kinds of bands could follow. Not only did they establish punk rock beachheads in literally every corner of the country; they inspired countless other bands to form and start doing it for themselves. The band’s selfless work ethic was a model for the decade ahead, overcoming indifference, lack of venues, poverty, even police harassment.

Black Flag was among the first bands to suggest that if you didn’t like “the system,” you should simply create one of your own. And indeed, Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn also founded and ran Black Flag’s label, SST Records. Ginn took his label from a cash-strapped, cop-hassled storefront operation to easily the most influential and popular underground indie of the Eighties, releasing classics by the likes of Bad Brains, the Minutemen, the Meat Puppets, Hüsker Dü, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, and many more.

SST and Black Flag in particular hit a deep and molten vein in American culture. Their fans were just as disaffected from the mainstream as the bands were. “Black Flag, like a lot of these bands, were playing for the people who maybe felt jilted by things or left out by things,” says the band’s fourth lead singer, Henry Rollins. “When you say, ‘Be all you can be,’ I know you’re not talking to me, motherfucker. I know I’m not joining the navy and I know your laws don’t mean shit to me because the hypocrisy that welds them all together, I cannot abide. There’s a lot of people with a lot of fury in this country—America is seething at all times. It’s like a Gaza Strip that’s three thousand miles long.”

Greg Ginn never really liked rock music as a kid. “I considered it kind of stupid,” he says. “I considered it just trying to interject some kind of legitimacy into making three-minute pop commercials, basically.” Ginn didn’t even own any records until he was eighteen and received David Ackles’s 1972 art-folk masterpiece American Gothic as a premium for subscribing to a local public radio station. The record opened a new world for Ginn; a year later he began playing acoustic guitar as a “tension release” after studying economics all day at UCLA.

Ginn had spent his early childhood with his parents and four brothers and sisters in a small farming community outside Bakersfield, California. His father earned a meager schoolteacher’s salary, so Ginn got used to cramped surroundings and living on limited means. “I never had new clothes,” says Ginn. “My dad would go to Salvation Army, Goodwill, and he would consider those expensive thrift stores—‘Salvation Army, that’s expensive!’ He would find the cheaper places.”

In 1962, when Ginn was eight, the family moved to Hermosa Beach, California, in the solidly white middle-class South Bay area a couple of dozen miles south of Los Angeles. Hermosa Beach had been a beatnik mecca in the Fifties, but by the time Ginn got there, it was a haven for surfers (and inspired Jan & Dean’s 1963 classic “Surf City”).

But while his peers were into hanging ten, Ginn disdained the conformity and materialism of surfing; a very tall, very quiet kid, he preferred to write poetry and do ham radio. A generation later he would have been a computer nerd. At the age of twelve, he published an amateur radio fanzine called The Novice and founded Solid State Tuners (SST), a mail-order business selling modified World War II surplus radio equipment; it became a small but thriving business that Ginn ran well into his twenties.

After learning to play an acoustic, Ginn picked up an electric guitar and began writing aggressive, vaguely blues-based songs, but only for himself. “I was never the stereotypical teenager,” Ginn said, “sitting in his room and dreaming of becoming a rock star, so I just played what I liked and thought was good.” Ginn’s music had nothing to do with the musical climate of the mid-Seventies, especially in Hermosa Beach, where everybody seemed to be into the British pomp-rock band Genesis. “The general perception was that rock was technical and clean and ‘We can’t do it like we did it in the Sixties,’ ” he said. “I wished it was more like the Sixties!”

It’s no wonder Ginn got excited when he began reading in the Village Voice about a new music called “punk rock” that was coming out of New York clubs like Max’s Kansas City and CBGB. Even before he heard a note, he was sure punk was what he was looking for. “I looked at punk rock as a break in the conformity that was going on,” says Ginn. “There wasn’t a specific sound in early punk rock and there wasn’t a specific look or anything like that—it seemed to be a place where anybody could go who didn’t fit into the conventional rock mode.”

Ginn sent away for the classic “Little Johnny Jewel” single by the New York band Television on tiny Ork Records. The music was powerful, brilliant, and it had nothing to do with Genesis or the slick corporate rock that dominated the music industry in the mid-Seventies; this music was organic in the way it was played, recorded, and, just as important, how it was popularized. It was hardly “three-minute pop commercials.”

Ginn was hooked.

By then Ginn had developed extraordinarily wide-ranging musical tastes. He dug Motown, disco, country artists like Merle Haggard and Buck Owens, and adored all kinds of jazz, from big band to early fusion; in the Seventies he was a regular at Hermosa Beach’s fabled jazz club the Lighthouse, where he witnessed legends like Yusef Lateef and Mose Allison. But besides his beloved B.B. King, there was only one group that Ginn adored more than any other. “The Grateful Dead—if there’s one favorite band I have, it’s probably that,” says Ginn. “I saw them maybe seventy-five times.”

But because Ginn was only a novice guitarist, none of those influences came through in his playing; he was simply making music to work off energy and frustration, and as generations of beginners before him had discovered, the quickest shortcut to a cool guitar sound was nasty, brutish distortion. Then, when he saw the Ramones play, Ginn “got a speed rush,” he said, “and decided to turn it up a notch.” The next logical step was to form a band.

In late ’76 a mutual friend introduced Ginn to a hard-partying loudmouth named Keith Morris; the two hit it off and decided to start a band. Morris wanted to play drums, but Ginn was convinced Morris should sing. Morris protested that he didn’t write lyrics and, besides, he was no Freddie Mercury. But punk had showed Ginn you didn’t need gold-plated tonsils to rock, and Morris eventually agreed. They drafted a few of Morris’s friends—“scruffy beach rat types who were more interested in getting laid and finding drugs than really playing,” Morris said—and began rehearsing in Ginn’s tiny house by the beach. In honor of their hectic tempos, they called the band Panic.

There was precious little punk rock to emulate at the time, so the band picked up the aggressive sounds they heard in Black Sabbath, the Stooges, and the MC5, only faster. “Our statement was that we were going to be loud and abrasive,” said Morris. “We were going to have fun and we weren’t going to be like anything you’ve heard before. We might look like Deadheads—at that point we had long hair, but the Ramones did, too—but we meant business.” They played parties to nearly universal disdain.

They soon moved their practices to Ginn’s space at the Church, a dilapidated house of worship in Hermosa Beach that had been converted into workshops for artists but was in effect a hangout for runaways and misfits. They got kicked out for making too much noise and found a new rehearsal space in the spring of ’77. They practiced every day, but since their bass player usually flaked out on rehearsals, Ginn had to carry much of the rhythm on his own and began developing a simple, heavily rhythmic style that never outpaced his limited technique.

A band called Wurm also practiced in the Church, and the two bands began playing parties together. Wurm’s bassist, an intense, sharp-witted guy named Gary McDaniel, liked Panic’s aggressive, cathartic approach and began sitting in with them. McDaniel and Ginn connected immediately. “He would always have a lot of theories on life, on this and that—he was a thinking person,” says Ginn. “He didn’t want to fit into the regular society thing, but not the hippie thing, either.”

Like Ginn, McDaniel, who went by the stage name Chuck Dukowski, was repulsed by mellow folkies like James Taylor and effete art-rockers. He was a student at UC Santa Barbara when he saw the Ramones. “I had never seen a band play so fast,” he said. “Suddenly you could point to a band and say, ‘If they can do it, why can’t we?’ ”

For their first couple of years, Panic played exclusively at parties and youth centers around the South Bay because the Masque, the key L.A. punk club, refused to book them. “They said it wasn’t cool to live in Hermosa Beach,” Ginn claimed, which is a way of saying that the band’s suburban T-shirt, sneakers, and jeans look flew in the face of the consumptive safety-pin and leather jacket pose of the Anglophilic L.A. punks. By necessity, Panic developed a knack for finding offbeat places to stage their explosive, anarchic performances, often sharing bills with Orange County punk bands, relatively affluent suburbanites who could afford things like renting halls and PA systems.

The party circuit had a very tangible effect on the band’s music. “That’s where we really developed the idea of playing as many songs in as little time as possible,” says Ginn, “because it was always almost like clockwork—you could play for twenty minutes before the police would show up. So we knew that we had a certain amount of time: don’t make any noise until you start playing and then just go hard and long until they show up.”

Their first proper show was at a Moose Lodge in nearby Redondo Beach. During the first set, Morris began swinging an American flag around, much to the displeasure of the assembled Moose. He was ejected from the building, but he donned a longhaired wig and sneaked back in to sing the second set. Eventually the band progressed to playing shows at the Fleetwood in Redondo Beach, where they built up such a substantial following that the Hollywood clubs couldn’t ignore them anymore, effecting a sea change in L.A. punk.

Early on Ginn met a cheery fellow known as Spot, who wrote record reviews for a Hermosa Beach paper. Ginn would sometimes stop by the vegetarian restaurant where Spot worked and shoot the breeze about music. “He was a nerd,” Spot recalls. “He was just an awkward nerd who was very opinionated. Couldn’t imagine him ever being in a band.” Later Spot became assistant engineer at local studio Media Art, which boasted cheap hourly rates and sixteen-track recording. When Ginn asked him to record his band, Spot agreed, figuring it would be a nice break from the usual watery pop-folk. “They only had six songs,” Spot recalls. “They could play their entire set in ten minutes.

“They were just goons and geeks,” he adds. “Definitely not the beautiful people.”

In January ’78 Panic recorded eight songs at Media Art, with Spot assistant engineering. But nobody wanted to touch the band’s raging slab of aggro-punk except L.A.’s garage-pop revivalists Bomp Records, who had already released singles by L.A. punk bands like the Weirdos and the Zeros. But by late 1978 Bomp still hadn’t formally agreed to release the record. So Ginn, figuring he had enough business expertise from SST Electronics and his UCLA economics studies, simply did it himself.

“I just looked in the phone book under record pressing plants and there was one there,” says Ginn, “and so I just took it in to them and I knew about printing because I had always done catalogs and [The Novice] so we just did a sleeve that was folded in a plastic bag. And then got the singles made and put in there.” Ginn got his younger brother, who went by the name Raymond Pettibon, to do the cover, an unsettling pen-and-ink illustration of a teacher keeping a student at bay with a chair, like a lion tamer.

A few months earlier they had discovered that another band already had the name Panic. Pettibon suggested “Black Flag” and designed a logo for the band, a stylized rippling flag made up of four vertical black rectangles. If a white flag means surrender, it was plain what a black flag meant; a black flag is also a recognized symbol for anarchy, not to mention the traditional emblem of pirates; it sounded a bit like their heroes Black Sabbath as well. Of course, the fact that Black Flag was also a popular insecticide didn’t hurt either. “We were comfortable with all the implications of the name,” says Ginn, “as well as it just sounded, you know, heavy.”

In January ’79 Ginn released the four-song Nervous Breakdown EP, SST Records catalog #001. It could well be their best recording; it was definitely the one by which everything after it would be measured. “It set the template—this is what it is,” Ginn said. “After that, people couldn’t argue with me as to what Black Flag was or wasn’t.”

With music and lyrics by Ginn, the record is rude, scuzzy, and totally exhilarating. With his sardonic, Johnny Rottenesque delivery, Morris inflates the torment of teen angst into full-blown insanity: “I’m crazy and I’m hurt / Head on my shoulders goin’ berserk,” he whines on the title track; same for the desperate “Fix Me” (“Fix me, fix my head / Fix me please, I don’t want to be dead”).

Drummer Brian Migdol left the band and was replaced by Roberto Valverde, better known as Robo, who originally hailed from Colombia. “A real sweet guy and super enigmatic,” recalls future Black Flag singer Henry Rollins. “He had a very shady past which he would not talk about.” The rumor that made the rounds was that Valverde had been a soldier in the notoriously corrupt Colombian army.

In July ’79 the band played an infamous show at a spring family outing at Manhattan Beach’s Polliwog Park, having told town officials they were a regular rock band. It didn’t take very long for the assembled moms and dads to figure differently. “People threw everything from insults to watermelons, beer cans, ice, and sandwiches at us,” wrote Dukowski in the liner notes to the Everything Went Black compilation. “Parents emptied their ice chests so that their families could throw their lunches…. Afterwards I enjoyed a lunch of delicatessen sandwiches which I found still in their wrappers.”

While the Hollywood punks tended to be spindly, druggy, and older, the suburban kids who followed Black Flag and other bands tended to be disaffected jocks and surfers, strapping young lads who rarely touched anything stronger than beer. And when they all gathered in one place, fights would break out and things would get broken. The most thuggish of the suburban punks were a crew from Huntington Beach, better known as the HB’ers. “The HB’ers were all leather jackets, chains, macho, bloodlust, and bravado, and exhibited blatantly stupid military behavior,” wrote Spot in his Everything Went Black liner notes. “It was never a dull moment.”

This new kind of punk rocker perplexed the local authorities. “All of a sudden you’re dealing with thick-necked guys who were drunk and could go toe to toe with some cops, guys who will get in a cop’s face,” says Henry Rollins. “They’re white and they’re from Huntington Beach and you can’t shoot ’em because they’re not black or Hispanic so you have to deal with them on a semihuman level. The sheer force of the numbers at the shows totally freaked the cops out to where they just said, ‘Don’t try to understand it, we’ll just squelch it. And how will we squelch it? We’ll just smash the hell out of ’em—arrest ’em for no reason, smack ’em on the head, intimidate the shit out of them.’ And boy it was intense.”

Police harassment blighted the early days of South Bay hardcore, and Black Flag was the lightning rod for most of it. It all started when Black Flag threw a party at the Church in June ’80. In the name of property values, Hermosa Beach was then in the midst of clearing out the last remnants of its hippie culture, and the town fathers were apparently intent on preventing bohemian youth culture from ever blighting their fair city again. The police showed up at the party and almost literally told Black Flag to get out of town by sundown. Conveniently, the band had scheduled the show for the eve of a West Coast tour, so they piled in the van, took off for San Francisco, and later returned to Redondo Beach. After a year or so they came back to Hermosa Beach and were promptly given the bum’s rush once again.

Between 1980 and 1981, at least a dozen Black Flag concerts ended in violent clashes between the police and the kids. And the more the band complained to the press about the police, the more the police hassled them and their fans. Not helping matters was the fact that the Black Flag logo was spray-painted on countless highway overpasses in and around Los Angeles. Then there was the flyer that got plastered all over town featuring a Pettibon drawing of a hand jamming a pistol in the mouth of a terrified cop. The caption read “Make me come, faggot!”

Ginn claims SST’s phone lines were being tapped, cops sat in vans across the street and monitored SST headquarters, and undercover police posing as homeless people sat on the curb in front of SST’s front door. Hiring a lawyer simply wasn’t an option—they couldn’t afford one. “I mean, we were thinking about skimping on our meals,” Ginn explains, adding, “It’s not like you’re part of society. There was no place to go. That’s what people just don’t get that haven’t been in that place. Because you don’t have any rights. If you don’t have that support, then the law is just the cop out there and what he tells you to do.” But the band never backed down, fueling even more ire from L.A.’s finest.

Starting in 1980, L.A. clubs began to ban hardcore bands. “That’s the last thing I thought would happen,” Ginn says. “I thought we’re pretty mild-mannered people and we don’t write songs about some sort of social rebellion; it’s basically blues to me. It’s personal, my way of writing blues.”

Rollins, who admittedly was not yet in the band when most of the harassment went down, believes much of the controversy was a Dukowskian plot. “Looking back at it, I think it was some press manipulation,” he says. “And to rouse some rabble.” If so, the plan backfired—what good was police harassment if you couldn’t get a gig?

Black Flag had booked their first tour, a summer of ’79 trip up the West Coast, hitting San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and up to Vancouver, British Columbia, when Morris, an admitted “alcoholic and a cokehead,” left the band to found the pioneering South Bay punk band the Circle Jerks. He was quickly replaced by a rabid Black Flag fan named Ron Reyes, aka Chavo Pederast. “He’d go real crazy at the gigs and we just thought he’d make a really good singer,” Ginn explains.

But Reyes quit two songs into a show at the Fleetwood in March ’80, and the band proceeded to play “Louie, Louie” for an hour, joined by a long succession of guest vocalists. “A guy named ‘Snikers’… jumped up and began singing ‘Louie, Louie’ and then proceeded to perform a most disgustingly drunken striptease during which cans, bottles, spit, sweat, and bodies began flying with a vengeance,” wrote Spot. “It was the finest rock & roll show I had ever seen.” For several shows afterward, the band played without an official lead singer—anyone who wanted to would come up and sing a song or two before getting yanked back into the crowd.

They convinced Reyes to come back and record the five-song, six-and-a-half-minute Jealous Again EP (released in the summer of ’80), a nasty nugget of low-rent nihilism, with Ginn’s guitar slashing all over the music like a ghoul in a splatter flick, the rhythm section pounding out boneheaded riffs at hectic speed, Reyes conjuring up a different species of temper tantrum for each track. Ginn’s lyrics were laced with satire, but it wasn’t very pretty—on “Jealous Again” the singer rails against his girlfriend, “I won’t beat you up and I won’t push you around / ’Cause if I do then the cops will get me for doing it.” And it was easy to miss the sarcasm of “White Minority”—“Gonna be a white minority / They’re gonna be the majority / Gonna feel inferiority.” The record was a harsh wake-up call for the California dream: for all the perfect weather and affluent lifestyles, there was something gnawing at its youth. Los Angeles wasn’t a sun-splashed utopia anymore—it was an alienated, smog-choked sprawl rife with racial and class tensions, recession, and stifling boredom.

Black Flag became more and more of a focal point for violence and condemnation. “The Black Flag Violence Must Stop!” proclaimed the title of one editorial. All the media hype was now attracting a crowd that was actually looking for violence—not that Black Flag did much to stop it. “Black Flag never said, ‘Peace, love, and understanding,’ ” says Rollins. “If it got crazy, we’d say, ‘Guess what, it gets crazy.’ We were the band that didn’t go, ‘Go gently into that night.’ One of the main rallying war cries for us was ‘What the fuck, fuck shit up!’ Literally, that was one of our slogans.”

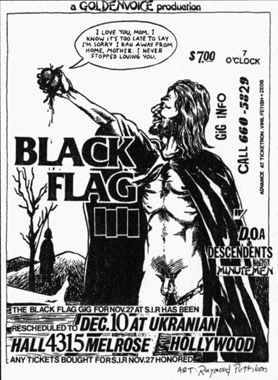

Refusing to give up, the band made a hilariously provocative series of radio ads to promote their shows, twitting the LAPD mercilessly. In one ad, a mobster tells the owner of the Starwood club that booking Black Flag was a big mistake. “Chief Gates says this is going to cost the whole organization plenty,” says the hoodlum. “We don’t need this.” An ad for a February ’81 show with Fear, Circle Jerks, China White, and the Minutemen at the Stardust Ballroom opens with a voice that says, “Attention all units, we have a major disturbance at the Stardust Ballroom…” “Chief Gates is in a real uproar,” says one cop, and his partner replies, “What the hell are we waiting for then, let’s go over there and beat up some of them damn punk rockers!”

Eventually the violence became too much for the police and the community. If Black Flag was to keep playing shows, they’d have to play them out of town. But back then literally only a handful of American indie punk bands undertook national tours; lower-tier major label bands did them as promotional loss leaders, something independent label bands couldn’t afford. Besides, there were few cities besides New York, L.A., and Chicago that had clubs that would even book punk rock bands. The solution was to tour as cheaply as possible and play anywhere they could—anything from a union hall to someone’s rec room. They didn’t demand a guarantee or accommodations or any of the usual perquisites, and they could survive that way—barely, anyway.

Ginn and Dukowski began collecting the phone numbers printed on various punk records and made calls to set up shows in far-flung towns. People were eager to help; after all, it was in everybody’s interest to do so. In particular, North American punk pioneers like Vancouver, B.C.’s D.O.A. and San Francisco’s Dead Kennedys shared what they’d learned on the road. “With those bands, we did a lot of networking, sharing information,” says Ginn. “We’d find a new place to play, then we’d let them know because they were interested in going wherever they could and playing. Then we would help each other in our own towns.”

Black Flag began making sorties up the California coast to play the Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco, doing seven in all before venturing out as far as Chicago and Texas in the winter of ’79–’80. Spot went along as soundman and tour manager, a job he would do, along with acting as SST’s unofficial house engineer, for several years. His assessment of the situation: “Smelly. It was everyone in a Ford van with the laundry and the equipment. It was uncomfortable.”

Wherever they went, they tried to play all-ages shows, even if it meant playing two sets, one for kids and one for drinkers. It was simply a way of making sure no one was excluded from their shows. But no matter how good their intentions, Black Flag’s reputation preceded them. “In some towns it was like people expected us to pull up with a hundred L.A. punks and try to destroy their club,” Ginn said. “We’re not out to destroy anybody’s club. We’re just trying to play music.”

By stringing together itineraries of adventurous venues who would host their virulent new brand of punk rock, bands like Black Flag, D.O.A., and Dead Kennedys became the Lewis and Clarks of the punk touring circuit, blazing a trail across America that bands still follow today. But Black Flag was the most aggressive and adventurous of them all. “Black Flag, back then, was the one that was opening up these places to these audiences,” says Mission of Burma’s manager, Jim Coffman. “It was because of their diligence—Chuck’s diligence. A lot of times you’d hear ‘Black Flag played there.’ And you’d say, ‘OK, we’ll play there then.’ ”

In June ’80, months after Reyes quit, the band still hadn’t found a replacement—and their West Coast tour was a week away. Then Dukowski bumped into Dez Cadena (whose father happened to be Ozzie Cadena, the legendary producer/A&R man who worked with virtually every major figure in jazz from the Forties through the Sixties). The rail-thin Cadena went to plenty of Black Flag shows, knew the words to all the songs, and got along fine with the band. Cadena protested that he’d never sung before, but in typical Black Flag fashion, Dukowski said it didn’t matter. Cadena agreed to give it a try. “This was my favorite band and these guys were my friends,” Cadena said, “so I didn’t want to let them down.”

Cadena worked like a charm, and his sincere, anguished bark—more hollering than singing—was a big change from the Johnny Rotten–inspired yowling of Morris and Reyes, and swiftly became a template for hardcore bands all around the South Bay and beyond. The band arguably reached the peak of its popularity with Cadena as lead singer. On the eve of a two-month U.S. tour, the band headlined a sold-out June 19, 1981, show with the Adolescents, D.O.A., and the Minutemen at the 3,500-seat Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, a feat they never again achieved. Noting the rowdiness and chaos, an L.A. Times piece on the show wondered, “Is the whole thing a healthy release of tension or yet another disturbing sign of the escalating violence in society?” And of course it was both.

On the other hand, not everybody thought slam dancing was such a great idea. “To me, they’re just like the guys who try to bully you at school,” fifteen-year-old Tommy Maloney of Canoga Park told the L.A. Times. “Who needs ’em? The shows would be a lot more fun if they found some other place to fool around.”

Cadena’s arrival coincided with the onset of the band’s heavy touring. Unfortunately his inexperience as a singer—coupled with his heavy smoking and some woefully underpowered PA systems—meant his voice crumpled under the constant strain. Eventually everyone realized it would be best if he moved to guitar and the band got a new singer.

Henry Garfield grew up in the affluent Glover Park neighborhood of Washington, D.C., same as another future indie rock powerhouse, Ian MacKaye. “Word spread around that there was a kid with a BB gun down on W Street,” MacKaye recalls. “So we went down to visit this kid and he was kind of a nerdy guy with glasses.” But MacKaye soon realized Garfield’s appearance was deceptive—his new acquaintance attended Bullis Academy, a hard-ass military-style school for problem kids. Garfield, MacKaye concluded, “was a toughie.” Moreover, Garfield had a makeshift shooting gallery in his basement, and soon MacKaye and his friends were coming over and firing BB guns, listening to Cheech and Chong records, and admiring Garfield’s pet snakes.

Garfield, an only child, didn’t come from as affluent a home as most of his friends and didn’t have a very positive self-image; not surprisingly, he often did whatever it took to fit in. “If it was the thing to do,” he says, “I would be the first person to be Peer Pressure Boy and go be part of the throng without thinking.”

Garfield’s parents had divorced when he was a toddler; he had a short attention span and was put on Ritalin. Thanks to “bad grades, bad attitude, poor conduct,” he got sent to Bullis, which favored corporal punishment. But instead of a disrespect for authority, the experience instilled in Garfield a very rigorous self-discipline. “It was very good for me,” he says. “I really benefited from somebody going, ‘No. No means no and you really are going to sit here until you get this right.’ ”

Despite Glover Park’s comfortable environs, “it was a very rough upbringing in a lot of other ways,” he says. “I accumulated a lot of rage by the time I was seventeen or eighteen.” Some of that rage stemmed from intense racial tensions in Washington at the time; Garfield, like many white D.C. kids of his generation, got beaten up regularly by black kids simply because of his race.

But much of that rage came from problems at home. “A lot of things about my parents made me very angry,” he says. He told Rolling Stone in 1992 that he had been sexually molested several times as a child; many of his spoken word monologues refer to a mentally abusive father. “Going to school in an all-boys school and never meeting any girls, that was very hard. I hardly met any women in high school and I really resented the fact that I was so socially inept because of being separated from girls in those years. There’s a lot of that stuff.

“Also,” he adds, “I’m just a freak.”

Garfield and his buddy MacKaye were big fans of hard rockers like Ted Nugent and Van Halen, but they hungered for music that could top the aggression of even those bands. “We wanted something that just kicked ass,” he says. “Then one of us, probably Ian, got the Sex Pistols record. I remember hearing that and thinking, ‘Well, that’s something. This guy is pissed off, those guitars are rude.’ What a revelation!”

By the spring of ’79 Garfield, MacKaye, and most of their friends had picked up instruments. Except Garfield literally picked up instruments. “I was everybody’s roadie,” he says. “I basically did that just to be able to hang out with all of my friends who were now playing. I was always picking up Ian’s bass amp and putting it in his car. Not that he couldn’t—he’s the man and I’m going to carry the bass amp for the man.”

But sometimes when Teen Idles singer Nathan Strejcek wouldn’t show up for practice, Garfield would convince the band to let him on the mike. Then as word got around that Garfield could sing—or, rather, emit a compelling, raspy howl—H.R., singer of legendary D.C. hardcore band the Bad Brains, would sometimes pull him up to the mike and make him bark out a number.

In the fall of ’80, D.C. punk band the Extorts lost singer Lyle Preslar to a new band that was being formed by MacKaye called Minor Threat. Garfield joined what was left of the Extorts to form S.O.A., short for State of Alert. Garfield put words to the five songs they already had, they wrote a few new ones, and these made up S.O.A.’s first and only record, the No Policy EP, released a few months after the band formed. In little over eight minutes, the ten songs took aim at things like drug users, people who dared ask Garfield what he was thinking, the way girls make you do dumb things, and the futility of existence, all in the bluntest of terms; the rest of the songs had titles like “Warzone,” “Gang Fight,” and “Gonna Hafta Fight.”

After releasing the EP on Dischord Records, which MacKaye and some friends had founded, they rehearsed at drummer Ivor Hanson’s house—and since Hanson’s father was a top-ranking admiral, his house happened to be the Naval Observatory, the official residence of the vice president and the top brass of the navy. Every time they practiced, they’d have to drive past armed Secret Service agents.

S.O.A. played a grand total of nine gigs. “All of them were eleven to fourteen minutes each in duration because the songs were all like forty seconds,” says Rollins, “and the rest of the time we were going, ‘Are you ready? Are you ready?’ Those gigs were poorly played songs in between ‘Are you ready?’s.”

Garfield spat out the lyrics like a bellicose auctioneer while the band banged out an absurdly fast oompah beat. Along with a few other D.C. bands, S.O.A. was inventing East Coast hardcore. “The reason we played short and so fast was because [original drummer Simon Jacobsen] never really played drums—he was just a really talented kid who picked it up,” Rollins says. “So we didn’t have much besides dunt-dun-dunt-dun-dunt-dun as far as a beat. And there wasn’t enough to sing about that you couldn’t knock out in a couple of words, like, ‘I’m mad and you suck.’ There wasn’t a need for a lead [guitar] section—you never even thought of that.”

Garfield had found his calling. Indeed, he was a classic frontman. “All I had was attitude,” he says, “and a very intense need to be seen, a real I-need-attention thing.”

Garfield quickly earned a reputation as a fighter at shows. “I was like nineteen and a young man all full of steam and getting in a lot of fights at shows, willingly, gratefully,” he says. “Loved to get in the dust-ups. It was like rams on the side of the mountain. I wasn’t very good but I enjoyed it very much.”

He eventually worked his way up to manager of the Häagen-Dazs shop in Georgetown and was making enough money to have his own apartment, a stereo, and plenty of records. It was a pretty cushy life for a twenty-year-old. But that was all about to change.

One day a friend handed Garfield and MacKaye Black Flag’s Nervous Breakdown EP, the one they’d read about in the L.A. punk fanzine Slash. It was a revelation. A few months later, in December ’80 MacKaye heard that Black Flag was going to be playing D.C.’s 9:30 Club, so he called SST, got Chuck Dukowski on the phone, and offered the band a place to stay—his parents’ house. They took him up on it. Garfield and all his punk buddies jumped at the chance to meet the band in person. “We’re like, ‘Whoa, you can go over there and touch the mighty Black Flag,’ ” he says. “We got to spend time with them. Here’s a band whose set blew you away, whose record blew you away, and they’re really cool people and you’re talking to a real live rock band who tours, who you admire. And that was a big deal.”

Dukowski took a shine to Garfield and gave him a tape of music the band had been working on. The songs connected heavily with Garfield, yet he couldn’t help feeling he could sing them better than Cadena did. Dukowski kept in touch with Garfield, writing letters, hipping him to bands like Black Sabbath and the Stooges, calling from the road and shooting the breeze about music and what was happening in the D.C. scene.

Black Flag returned to the East Coast later that spring, and Garfield drove up to New York to catch their show. Arriving hours early, he hung out with Ginn and Dukowski all day, caught their Irving Plaza show, then accompanied them to an unannounced late-night gig at hardcore mecca 7A. It was now the wee hours of the morning and Garfield, realizing he had to get back to D.C. in time to open the ice-cream store at 9 A.M., requested the I-hate-my-job screed “Clocked In.”

“And right before they went to play, I thought, ‘Well, I know how to sing this song,’ and went, ‘Dez!’—gesturing toward the mike—‘Can I sing?’ ” he says. “And he went, ‘Fuck yeah!’ So I kind of jumped up onstage and everyone else in Black Flag was like, ‘All right, Henry’s going to sing. Cool!’ And they launch into the song and I sang the song like I thought it should be sung. I went for it with extreme aggression. And everyone in the crowd was like, ‘Whoaaaa.’ I got an immediate reaction. I watched people in the crowd go, ‘Fuck yeah!’ I remember looking over at Dukowski, who’s looking over at me, going, ‘Yeah. This is happening.’ ” Dukowski had just recognized that Garfield might be the lead singer they’d been looking for.

The song finished, Garfield dashed offstage, hopped into his beat-up old Volkswagen, and drove straight back to Washington.

A couple of days later, Garfield got a call at the ice-cream store: it was Dez Cadena, inviting him to come up to New York and jam. They’d cover the train fare. Garfield was a little puzzled. “I thought they were still up there and bored and wanted one of their buddies to come hang out with them,” he says. Cadena said he was switching to guitar and the band needed a new singer.

Garfield was staggered. “I’m like, ‘Holy shit. Am I being asked to audition for Black Flag?’ ” he says. “What a huge, monstrous proposition to a barely twenty-year-old guy with an extremely normal background. So I went, ‘I’m on my way.’ ”

Garfield knew about Ginn’s and Dukowski’s wide-ranging musical tastes and had ingratiated himself by introducing them to exotica like Washington, D.C.’s unique go-go music. In doing so, Garfield had shown he had the stylistic range to develop with the band and move on from hardcore’s already stifling loud-fast equation. “Henry,” says Ginn, “was somebody who we felt could break out of that narrow mode.”

Garfield made a 6 A.M. train the following morning and was soon standing in a dingy East Village rehearsal room with a microphone in his hand. “They said, ‘OK, what do you want to play?’ ” he says. “And I remember looking at Greg Ginn and saying, ‘Police Story.’ ” Then they ran through virtually every song in their set, with Garfield simply improvising to songs he didn’t know. Then they did it all over again.

“OK, time for a band meeting,” Dukowski announced. “You sit here,” he ordered Garfield. When they came back after a few minutes, Dukowski said simply, “OK.” “OK what?” Garfield replied. “OK, YOU WANT TO JOIN THIS BAND OR WHAT?” Dukowski thundered.

Garfield was stunned. Then he accepted. They sent him back to D.C. with a folder full of lyrics that he was to learn by the time they hooked up on tour in Detroit.

When he got home, he called his trusted friend Ian MacKaye and asked his advice. “Ian, should I do this?” Garfield asked.

“Henry,” MacKaye simply replied, “go.”

Garfield quit his job, left his apartment, sold his records and his car, and bought a bus ticket to Detroit.

Cadena wanted to finish out the tour as vocalist, so Garfield hauled equipment, watched the band at work, and sang at sound check and during the encores all the way back to Los Angeles. Much to Garfield’s relief, Cadena liked his singing. “It was my favorite band, and all of a sudden I’m the singer,” he says. “It was like winning the lottery.”

But being in Black Flag was not always a day at the beach. The third day of the tour, at Tut’s in Chicago, Dukowski picked up his bass and brained a bouncer who was beating up a girl. Garfield was shocked. “That was a very bad time,” he remembers. “The bouncer got stitched up and made it back to the set while we were still playing, wanting to throw down. We barely got out of there…. I’d been in Black Flag forty-eight hours at that time. ‘OK, so this is what it’s going to be.’ And it was.”

Garfield set out doing what so many come to California to do: reinvent himself. One of the first things he did upon arrival in L.A. was to get the Black Flag bars tattooed on his shoulder; and as a way of distancing himself from his troubled family life, he now called himself Henry Rollins, after a fake name he and MacKaye used to use.

Rollins was now in a much different world. For instance, there was Mugger, who worked at SST and roadied for the band. Mugger was a tough teenage runaway who was often so broke he’d have to eat dog food and bread, wadded up into a ball and downed very fast. This was not the type of fellow Rollins grew up with in Glover Park. “I stupidly asked Mugger—we were going to go out in the fall on tour—I go, ‘Mugger, how are you going to go on the road with us?’ ” Rollins says. “He’s like, ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Well, you’ll be in school.’ And he started laughing. He says, ‘Henry, I dropped out of school in sixth grade.’ ”

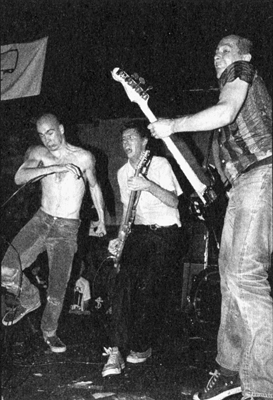

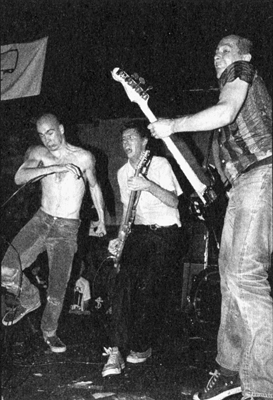

HENRY ROLLINS, GREG GINN, AND CHUCK DUKOWSKI AT AN AUGUST 1981 SHOW AT THE NOTORIOUS CUCKOO’S NEST IN COSTA MESA—ONE OF ROLLINS’S FIRST BLACK FLAG SHOWS EVER.

© 1981 GLEN E. FRIEDMAN. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE BURNING FLAGS PRESS BOOK, FUCK YOU HEROES

Band practices were attended by teenage runaways and other young people living on the fringe. “These people I started meeting, these punk rock kids, were dope-smoking, heroin-checking-out, ‘lude-dropping people who didn’t go to school,” says Rollins. “They lived on the street or scammed here or there.”

The new experiences continued for Rollins after his inaugural tour with Black Flag, a short trip up the California coast that autumn, when they came home to find that they’d been kicked out of their Torrance offices and had to stay with some “lazy slacker hippie punks” at an overcrowded crash pad in Hollywood. And once the police figured out Rollins was in Black Flag, he got the full treatment. “I got hassled three nights a week,” Rollins says. “And it was scary. They’d come out of the car and twist your arm behind your back and say things like, ‘Did you just call me a faggot?’ I’d go, ‘No, sir, I didn’t say anything.’ ‘Did you call me a motherfucker?’ ‘No.’ ‘You want to fight me?’ ‘No, sir.’

“That really scared me,” Rollins adds. “It freaked me out that an adult would do that. Then I learned that cops do all kinds of shit. My little eyes were opened big time.”

Rollins also had to get used to the powerful, diverse personalities within the band. Ginn, a slow, deliberate speaker some seven years Rollins’s senior, was “the introspective, quieter guy with immense power, but not showing his cards,” Rollins says. “You have no idea how he thinks, what he thinks, what occurs to him. He’s a super enigmatic guy to me.”

Ginn was also a hard worker, “very principled, with the most monster work ethic of any single human being I’ve ever encountered in my life to this day,” says Rollins. “If it took twenty hours, he did twenty hours. You’d say, ‘Greg, aren’t you tired?’ And he go, ‘Yeah.’ He would never, ever complain.”

Ginn’s strong, silent temperament was attractive and inspiring, especially to Rollins, who had learned to idolize such types back at Bullis. Those around Ginn would feel honored if he spoke even a few words to them, but the flip side to that distance was Ginn’s ability to dispense a devastatingly cold shoulder. “The silent treatment was the worst,” Rollins recalls. “You never got yelled at; you just kind of got scowled at.” In Black Flag, adds SST’s Joe Carducci, “everything was withheld and communicated sort of telepathically in bad vibes.”

Chuck Dukowski was something else altogether. Dukowski was “super charismatic—this guy had lightning bolts of ideas and rhetoric and hot air just coming off him,” Rollins says. “I don’t mean hot air like he was just talking, but always throwing out ideas, always asking questions, wanting to know everything—‘What are you reading?’ ‘Why did you like that book?’ ‘What would you do if someone tried to kill you?’ Really intense shit. ‘Would you eat raw meat to survive?’ ‘Would you fuck naked outside in public if you had to, to live?’ He was this bass-wielding Nietzschean, just an explosive character.

“One of Dukowski’s things was give everybody guns and a lot of people are going to die and after a while it will all get sorted out,” says Rollins. “That’s the kind of rhetoric Dukowski would spew in interviews. It was like, ‘Chuck, whoa…’ And he would start laughing hysterically, like in this weird high-pitched laughter. I think he was more just abstracting his rage.”

Dukowski, although not a technically gifted bassist, played with unbelievable intensity, throwing every molecule of his being into every note; he had simply willed himself into becoming a compelling musician. While Ginn was the band’s fearless leader, Dukowski, with his restless intellect and 24-7 dedication to the band, was its revolutionary theoretician and spiritual mainspring—a regular mohawked Mephistopheles. Dukowski set about indoctrinating Rollins into the Black Flag mind-set, goading him to the same intensity. Dukowski recognized that with some discipline and intellectual underpinning, his protégé was capable of some dizzying heights.

At a 1982 show in Tulsa, two people showed up. Rollins was downhearted, but Dukowski straightened him out, telling him that although there might be only a couple of people there, they came to see Black Flag and it’s not their fault nobody else came—you should play your guts out anytime anywhere and it doesn’t matter how many people are there. That night Rollins dutifully gave it everything he had.

At one point Dukowski urged Rollins to try LSD. “It will help you not be such an asshole,” Rollins recalls Dukowski telling him. Rollins was opposed to drugs, but his desire to fit into the band and please Dukowski and Ginn overruled his principles. As Rollins puts it, Dukowski “was such a big influence on me. If he said to jump off a roof, I would say, ‘Which roof?’ ” Rollins eventually began taking large quantities of acid on later Black Flag tours, using it to skin-dive into the deepest, darkest depths of his soul and bring some disturbing discoveries back to the surface.

Black Flag had tried recording material for their first album with Ron Reyes, who turned out to be studio-shy, then tried again with Cadena, but it didn’t come out to their satisfaction. The third time, with Rollins, proved to be a charm.

Ginn disdained most hardcore because it didn’t swing—the rhythms were straight up and down, with no lateral hip shake. To preserve the subtle but all-important swinging quality, he’d start the band playing new songs at a slow tempo, establishing a groove, and then gradually speeding it up at each practice, making sure to maintain that groove even at escape-velocity tempos. Very quickly Rollins abandoned the spitfire bark he’d used with S.O.A. and began to swing with the rest of the band. Just a few months after he’d joined, he’d already begun to redefine the sound not only of Black Flag but of hardcore itself.

Released in January ’82, Damaged is a key hardcore document, perhaps the key hardcore document. It boiled over with rage on several fronts: police harassment, materialism, alcohol abuse, the stultifying effects of consumer culture, and, on just about every track on the album, a particularly virulent strain of self-lacerating angst—all against a savage, brutal backdrop that welded apoplectic punk rock to the anomie of dark Seventies metal like Black Sabbath.

The songs took fleeting but intense feelings and impulses and exploded them into entire all-consuming realities. So when Ginn wrote a chorus like “Depression’s got a hold of me / Depression’s gonna kill me,” it sounded like the whole world was going to end. “That was Black Flag: when you lose your shit,” says Rollins. The music was the same way—blitzkrieg assaults so completely overwhelming, so consuming and intense that for the duration of the song, it’s hard to imagine ever listening to anything else.

Hardcore’s distinctive mix of persecution and bravado crystallized perfectly in the refrain of the opening “Rise Above,” as definitive a hardcore anthem as will ever be penned: “We are tired of your abuse! / Try to stop us, it’s no use!” goes the rabble-rousing chorus. But most songs are avowals of suicidal alienation, first-person portraits of confused, desperate characters just about to explode—“I want to live! I wish I was dead!” Rollins rants on “What I See.” Occasional humor made the anguish both more believable and more horrific, as in the sarcastic “TV Party”—“We’ve got nothing better to do / Than watch TV and have a couple of brews,” sings a charmingly off-key guy chorus over a goofy quasi-surf backing track.

Musically, the six-minute “Damaged I” is an anomaly—loud but not fast, it is based on a slowly trudging guitar riff with Rollins ad-libbing a psychodrama about being ordered around and abused, then retreating into a protective mental shell. The last sounds of the song—and the record—are Rollins barking, “No one comes in! STAY OUT!” It’s hard not to read it as straight autobiography.

Today Damaged is easily assimilated as hardcore, but at the time there was little precedent for music of such scathing violence. Yet Ginn’s explanation was typically matter-of-fact: “People work all day and they want a release,” he told the L.A. Times. “They want a way to deal with all the frustrations that build up. We try to provide that in our music.”

The album—and Rollins in particular—introduced an unforgiving introspection and a downright militaristic self-discipline. Perhaps because he was trying to make sense of his childhood traumas, Rollins threw himself headlong into Ginn’s psychological pain research. Rollins harbored huge amounts of anger and resentment, and Black Flag’s violent music unleashed his pent-up aggressions in a raging torrent.

Ginn and Dukowski had finally found their boy. “What I was doing kind of matched the vibe of the music,” Rollins explains. “The music was intense and, well, I was as intense as you needed.”

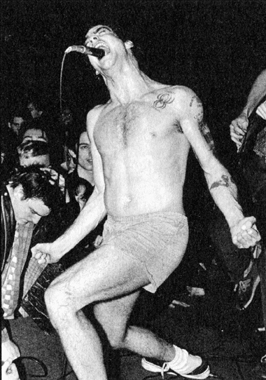

With his tattoos, skinhead, square jaw, and hoarse, martial bellow, Rollins became a poster boy for hardcore—unlike the older Dukowski and Ginn, Rollins looked like he could have been an HB’er. And like so many punks, parental and societal neglect had left him angry and alienated as hell. As the band plugged in and tuned up, Rollins would stalk the stage like a caged animal, dressed only in black athletic shorts, glowering and grinding his teeth (to get pumped up before a show, he’d squeeze a treasured number thirteen pool ball he’d taken from a club in San Antonio). Then the band would throw down the hammer, and the entire room would turn into a chaotic whirlpool of human flesh, its chance collisions oblivious to the rhythm of the music. Rollins’s copious sheen of sweat would rain down on the first few rows in a continuous shower while his anguished howling tore through Ginn’s electric assault like a blowtorch through a steel fence.

Robo played as if he were fending off attacks from his drums and cymbals. Dukowski tore sounds from his bass with utmost vengeance, doubling over and grimacing with the effort, banging his head and screaming at the audience, far from any microphone, while his fingers pummeled the strings like pistons. Ginn played in a spread-legged stance, making occasional lunges like a fencer, shaking his head from side to side as if in disbelief of his own ecstacy while his guitar barked like a junkyard dog, utterly unencumbered by anything that would make it sound melodious.

Opening for the Ramones at the Hollywood Palladium in the fall of ’82, Black Flag suffered from bad sound, but as one reviewer put it, “Rollins still carried the show with his truly menacing persona. He spit out the lyrics, convulsing to the beat, grinding his hips blatantly. Such a gruesome and intimidating display of rock aggression and frustration was hardly endearing, but like a high-speed car crash, you couldn’t keep your eyes—or ears—off them.” Another writer observed that Rollins was “a cross between Jim Morrison and Ted Nugent. No wonder the kids eat him up.” A larger-than-usual contingent of L.A.’s finest guarded the venue, blocking off some surrounding streets, as helicopters hovered overhead. The show went off without incident.

The media, from local fanzines all the way up to the Los Angeles Times, had the field day with the band’s notoriety. One skateboard magazine claimed the band had “detonated explosive riots at numerous gigs,” which was an exaggeration, although a show at the Polish Hall in Hollywood resulted in a bout of bottle and chair throwing that caused $4,000 in damage to the building as well as one arrest and two injured cops.

Boston Rock interviewer Gerard Cosloy asked why they didn’t try to stop violence at their shows. Dukowski responded with a succinct summation of the punk principle of anarchy. “Do we have a right to act as leaders, to tell people how to act?” Dukowski replied. “The easy solution isn’t a solution, it’s the fucking problem. It’s too easy to have someone tell you what to do. It is harder to make your own decision. We put a certain amount of trust into the people that come to see us.”

“Through interviews like this,” Ginn added, “maybe we can let people know what we do stand for, that we’re against beating people up, that we’re against putting people down because they have longer hair. We’ve made our statement, but we won’t prevent people from listening to something else, dressing some other way, or doing what they want. We aren’t policemen.”

Still, anyone who looked remotely like a hippie stood a good chance of getting roughed up at a Black Flag show. Maybe that’s part of the reason Ginn started growing his hair after Damaged, with Rollins and the rest of the band soon following suit—it was yet another way to twit their increasingly conformist audience. “We’re trying to always make a statement that it doesn’t matter what you’re wearing,” said Ginn. “It’s how you feel and how you think.”

Damaged made a fairly big impact in Europe and England, especially with the press, who were fascinated by the revelation that there was a really radical punk rock scene developing in the beach communities of Southern California, which they had previously looked on as an idyllic promised land, seemingly the last place where kids would flip a musical middle finger at society. “And it caused certain people to think, ‘Well, is this legitimate?’ ” says Ginn. “There’s that element of ‘This is wrong, coming from this place. People like that should be coming from Birmingham, England. You guys have it good.’ But when you’re surrounded by Genesis fans, I don’t know how idyllic that is. When you’re surrounded by that materialistic kind of a thing and you’re looking for something deeper than that, then that’s not an ideal environment.”

A December ’81 tour of the U.K. was a nightmare: freezing cold conditions, regular physical attacks from skinheads and rival English punk bands, and all manner of bloodshed onstage—at one show Ginn bled profusely after someone threw a bullet at his head; he staggered offstage, but not before angrily heaving a metal folding chair into the crowd. They even missed their first flight home.

Once the Damaged album was out, the band toured from early May all the way through mid-September ’82, a long, grueling trek. But their headlong momentum was about to come to a grinding halt.

SST had been selling its releases to small distributors at a deliberately low list price. But because those distributors usually sold import records, their releases usually wound up in specialty shops, unthinkingly stuck in the import section and at top-dollar import prices. Being a punk rock band on an independent label, Black Flag would never appear in the rock sections of ordinary record stores, alphabetized between Bad Company and Black Sabbath, where Ginn felt they belonged. So he decided to take Black Flag’s next record to a mainstream distributor. Many larger independent distributors wouldn’t even return SST’s phone calls, but one major did—MCA.

As part of the bargain, Ginn agreed to corelease the Black Flag album with Unicorn, a small label distributed by MCA. But in 1982, just as the album was to go out to stores, complete with the MCA logo on it, someone from Rolling Stone allegedly bad-mouthed Black Flag to MCA distribution chief Al Bergamo. Bergamo abruptly announced it would be “immoral” to release Damaged, claiming the album was “anti-parent, past the point of good taste.” “It certainly wasn’t like Bob Dylan or Simon and Garfunkel and the things they were trying to say,” he added.

Black Flag claimed they’d warned MCA of the record’s content, but that MCA, convinced the band would sell a lot of records, looked the other way. In his book Rock and the Pop Narcotic, Joe Carducci, who began overseeing sales, promotion, and marketing for SST in 1981, claimed MCA’s disapproval of the content was a red herring—the real reason was that Unicorn was so deeply in debt to MCA that it made no fiscal sense for MCA to continue the relationship; Black Flag’s “anti-parent” lyrics were just an excuse to sever ties with Unicorn.

So the band went to the pressing plant and put stickers with Bergamo’s “anti-parent” quote over the MCA logo on twenty thousand copies of the record. Then a tangle of lawsuits erupted when SST claimed that Unicorn didn’t pay SST’s rightful royalties and expenses for the album.

Unicorn countersued and got an injunction preventing Black Flag from releasing any further recordings until the matter was settled. When SST issued the retrospective compilation of unreleased Black Flag material called Everything Went Black with no band credit on it, Unicorn hauled SST into court in July ’83 and painted the band as, in Ginn’s words, “some kind of threat to society.” The judge found Ginn and Dukowski, as co-owners of SST, to have violated the injunction and sent them both to L.A. County Jail for five days on a contempt of court citation.

Upon his release, Ginn was ever the stoic. “He wouldn’t even discuss it,” Rollins says. “He just said, ‘Practice is at seven.’ He didn’t discuss it. I’m not kidding—not a word. I have no idea what it was like for Greg Ginn in jail. He said nothing except he got on the bus to go to County, he had a sandwich or some kind of food in his front pocket, and a guy reached over the seat and took it from him.”

Ginn still won’t say much about his experience in jail, deferring to people who have spent much longer periods of time in far worse prisons. “It’s not something I would recommend” is all he’ll say. “It’s a very demeaning thing. And I’d recommend to anybody that they try to stay out of there.”

Finally, Unicorn went bankrupt in late 1983 and Black Flag was free to release records again.

But the ordeal had taken a heavy toll on Black Flag. Damaged had gone out of print and the legal fight had drastically curtailed touring—a heavy blow to the band’s popularity, not to mention their income. And all the strife, tension, and poverty was causing considerable turnover in the band. “People would get worn out,” says Ginn. “Seven guys living in the same room and touring for six months and then still having debts hanging over our head.”

By this point Robo was long gone. A Colombian national, he’d encountered visa problems at the end of the December ’81 U.K. tour and couldn’t come back into the country. (The band had flown in the Descendents’ Bill Stevenson to finish the tour with a week of East Coast shows. Stevenson lived down the street from Ginn; the Descendents—a smart, jumpy, pop-punky quartet given to titles like “I Like Food” and “My Dad Sucks”—was Black Flag’s brother band and shared their practice space.)

In the first half of ’82, a slight, corkscrew-haired sixteen-year-old known only as Emil began drumming with the band. He didn’t last long. The story goes that Emil’s girlfriend was pressuring him to quit the band and spend more time with her and that when Ginn got wind of this, he convinced Mugger to turn Emil against his girlfriend by claiming he’d slept with her. The strategy backfired, prompting a brawl with Mugger. Emil left in the middle of the marathon 1982 U.S. tour and was replaced by D.O.A.’s incredible Chuck Biscuits.

On a West Coast tour, that lineup played a grange hall in the tiny northern Washington town of Anacortes. “Henry was incredible,” raved writer Calvin Johnson, reviewing the show for the fanzine Sub Pop, “pacing back and forth, lunging, lurching, growling; it was all real, the most intense emotional experiences I have ever seen.”

Unfortunately, Biscuits lasted only several months. Biscuits, Ginn says, would not agree to Black Flag’s rigorous rehearsal schedule, which was six days a week and up to eight hours a day. “Greg Ginn practices were like the long march to the sea,” Rollins says. “Talk about a work ethic, he is like Patton on steroids.

“Black Flag was a bunch of very disciplined people,” Rollins continues. “Very ambitious, super disciplined. Being in that band was like getting drilled all the time. You practiced the set once, twice a night. We had band practice six, seven days a week. On the weekends I had to rest my voice. I’d go, ‘Greg, I’m going to a friend’s house this weekend because she’s going to feed me. And I will be back on Monday and I’m not going to sing Saturday and Sunday because I’m going to give my voice a rest.’ And Greg would be kind of pissed. Greg would be in there seven days a week. That’s how Black Flag was. There was never any anarchy in our lifestyle.”

Rollins’s desire to occasionally rest his voice wasn’t the only thing that alienated him from the rest of the band. “I never talked a lot to Henry,” Ginn says. “Henry was always kind of the loner type of person.” Another part of Rollins’s isolation stemmed from the fact that he didn’t smoke pot and instead drank vast quantities of coffee, meaning he was amped up on caffeine while others were stoned.

“Understand another thing: Black Flag was never a group of friends,” says Rollins, “never a big camaraderie.” Dukowski did become Rollins’s sardonic guru, but Rollins never really befriended the enigmatic Ginn. “You never knew where you stood with Greg,” says Rollins. “Newer recruits would come to me and say, ‘Does Greg like me? How am I doing with Greg?’ And I’d go, ‘You’re doing fine, just don’t worry about it, play your song, play like Greg says, it’s cool.’ ”

Bill Stevenson rejoined Black Flag in the winter of ’82–’83, in the depths of the Unicorn fracas. Stevenson was a bright guy and knew about songwriting and production, which was both good and bad—although he could assist Ginn on both those fronts, it sometimes meant he would butt heads with him, too.

They set off on a U.S. tour that January, then went over to Europe for a tour with the Minutemen, in the midst of the coldest winter the Continent had seen in years. The way Rollins tells it, the whole tour was an unending succession of unheated clubs and punk rock squats, starvation, misery, and pain; to top it off, their van got repossessed. Very early in the tour, Rollins had already grown disenchanted with at least one of his tourmates. “Mike Watt never stops talking,” Rollins wrote in his tour diary, later published as Get in the Van. “I think I’m going to punch Mike Watt’s lights out before this is all over.”

But he held far more contempt for the people in the audience. At a German show, “I bit a skinhead on the mouth and he started to bleed real bad,” wrote Rollins. “His blood was all over my face.” In Vienna a member of the audience bashed Rollins in the mouth with the microphone; people spat on his face; someone burned his legs with a cigar; he tried to protect a stage diver from some overzealous bouncers and got punched in the jaw—by the stage diver—for his trouble. When the police came, the crowd beat them up, took their uniforms, and allegedly killed their police dog.

When a rowdy punk pestered Ginn during a show in England, Rollins cleaned his clock. “His mohawk,” wrote Rollins, “made a good handle to hold on to when I beat his face into the floor.” Later Ginn berated Rollins for the beating, calling him a “macho asshole.” Rollins felt Ginn would feel differently if he’d been attacked. “I don’t bother talking to him about it because you can’t talk to Greg,” Rollins wrote. “You just take it and keep playing. Whatever.”

When they pulled up to one Italian club, there was a crowd of menacing-looking punks waiting for them. The Italian punks circled the van and started rocking it and pounding on the windows. The band was getting scared, trying to figure out how to get into the club without sustaining grievous bodily harm. At last they burst out of the van and made a run for it. The rabid mob immediately surrounded them—and began hugging and kissing the band and thrusting presents into their hands.

While Black Flag was sorting out its legal situation, leading hardcore bands like Minor Threat had broken up, the Bad Brains went on indefinite hiatus, and the hardcore scene had become absurdly regimented and inbred, both socially and musically. Raymond Pettibon’s illustration for Black Flag’s 1981 Six Pack EP had been uncannily prescient: a punk who had literally painted himself into a corner. Black Flag’s post-Damaged music was devoted to charting a course out of that stylistic cul-de-sac. This meant going back to bands like the Stooges, the MC5, and especially Black Sabbath for ways to convey aggression and power without resorting to the cheap trick of velocity (although the band stuck with the even cheaper trick of volume). So Ginn slowed down the new Black Flag music, reasoning that although a speeding bullet can pierce a wall, a slow-rolling tank does more damage.

But, shrewdly realizing that plenty of other bands, bands he had plenty of contempt for, would take his ideas, turn them into a formula, and sell more tickets and records than Black Flag did, Ginn withheld the new approach from outsiders. “They didn’t want to play the new songs because there were too many bands ready to steal the ideas that they were working on,” says Joe Carducci. “A lot of people were looking to them for ‘What do you do with this after you speed it up to the breaking point, then what do you do, Greg?’ So Greg would keep that stuff…. He didn’t play it in front of other people.”

But Ginn would have to make changes in the band if he was to realize his new musical vision. As a guitarist, Dez Cadena was conservative, leaning toward generic classic rock like Humble Pie and ZZ Top, which Ginn just could not countenance any longer. Cadena left the group in August ’83 to form his own band, DC3, which recorded several classic rock-inspired albums for SST.

And by the fall Chuck Dukowski left the group, too. Ginn was a hard man to work for, but by this point Dukowski was getting the brunt of his ambivalence. “Greg was not going to be pleased with anybody, no matter who they were, on whatever level,” says Joe Carducci. “There’s that sense with Greg that it’s never good enough.”

“I felt that we had reached a dead end in terms of the music that we were playing together,” Ginn says, adding that his musical chemistry with Dukowski was more a product of endless practicing than natural affinity. “In a way, I always felt that it was kind of glued together in a certain respect, instead of a real natural groove.” Ginn had felt this for a long time, but Dukowski was so fully dedicated to the band, such an integral part of its esprit de corps, that letting him go was difficult.

Ginn couldn’t bring himself to criticize Dukowski outright and instead made life difficult for him in the hopes that Dukowski would quit on his own accord. But Dukowski had pinned too much of his self-image and energies on the band to just leave, and the stalemate lingered for many agonizing months. Finally, without consulting anyone else in the band, Rollins simply took it upon himself to end the standoff and fire Dukowski.

Even though Dukowski didn’t play on the band’s next album, My War, it includes two songs he wrote—one of them the title track—so the feelings couldn’t have been that hard on either side. Dukowski also went on to become the band’s de facto manager and the hardworking head of SST’s booking arm, Global Booking. This was a masterstroke, as relentless touring would literally put the label’s bands on the map and help establish SST’s dominance of the indie market in the coming decade.

But the departure of his partner in crime took its toll on Ginn. For the first five years, Ginn felt no need to rule the band with an iron hand—he actually seemed to enjoy the chaos. “But then by ’83, he’d taken total control of the band,” says Carducci. “And he didn’t seem to be enjoying himself at all.”

The band’s work ethic only intensified. “Greg was a fanatic and most people are not,” says Carducci. “He took the business down to a level that was beneath the level lightweights could handle: they couldn’t handle sleeping in the van, they couldn’t handle not knowing where they were going to stay, they couldn’t handle the clubs.” On the road the band got $5 a day. Toward the end they made ten, and on the final tour, twenty. “If we got a flat tire, we would get an old tire that was discarded in the back of a gas station that they’d given up on and put that on,” says Ginn. “It was real bare bones.”

On the early tours, audiences could vary anywhere between twenty-five and two hundred. As their popularity climbed, they eventually found themselves playing six months of the year or more. But when the tours began lasting that long, it also meant that the band members couldn’t hold down significant day jobs once they got home, and that’s when things got really tough.

Ginn’s parents would often help out with food and even clothing; Mr. Ginn would buy used clothing for pennies a pound, and the band would take a big sack of it on tour, pulling whatever they liked out of the grab bag. So much for punk fashion.

“Without the Ginn family,” says Rollins, “there would not have been a Black Flag.” Mr. Ginn would rent vans and Ryder trucks for the band and was so proud of his son that when he’d teach classes at Harbor College, he’d often have the Black Flag insignia painted on the pocket of his button-down shirts. Often Mr. Ginn would make a mess of grilled cheese sandwiches, buy a few gallons of apple juice and some fruit at a farm stand, and bring it to SST. “We would eat cheese sandwiches, avocados that were five for a dollar, and apple juice for days,” says Rollins. “Those things would get moldy, you’d just scrape the mold off and keep eating.”

It sounds pretty rough, but Ginn, ever the stoic, downplays the hardship. “I think people would consider it rough but that’s all relative—there’s things I would consider rough, like war,” says Ginn. “I never considered it rough. I considered it not having money, but I always think, if you’re asleep on a floor, how can you tell the difference anyway—you’re asleep.”

Perhaps because Rollins had grown up relatively affluent and an only child, he sought as much comfort and privacy as possible. When the band came back to L.A., he’d find a friend with an extra bedroom or sleep at the Ginn family’s house rather than live in communal squalor with the band. “Even though he really tried, he was never comfortable with that kind of existence,” says Ginn. “Which isn’t a bad thing—I think that may be more typical of the average person. Obviously, I guess it is.”

Rollins was over at the Ginns’ house so often that they finally invited him to live there. They offered him a bedroom, but Rollins chose what he called “the shed,” a small, furnished outbuilding that had been Mr. Ginn’s study. Rollins’s insinuation into his family annoyed Greg Ginn to no end; he got even more annoyed when Mrs. Ginn asked if her son smoked marijuana and Rollins said yes.

The rest of the band lived where they rehearsed. “Even at the end, we lived with seven people in one room,” says Ginn. “And we always lived in those kind of situations—living where we practiced, or whatever, living in vans and that kind of stuff. Pretty early on, materially we didn’t fit in at all.”

“There were some droughts there where you were eating a Snickers bar and you’d walk in and someone would say, ‘Where’d you get that?’ ” Rollins recalls. “You go, ‘Well, I bought it.’ ‘Where’d you get the money to get that?’ ‘Uh, OK, I took a dollar out of a cash order.’ That’s how broke we were.” Rollins’s mother would occasionally send him a twenty-dollar bill and he’d splurge on a pint of milk and a cookie from the 7-Eleven. “I’d say, ‘Well, I’m going out for a walk,’ ” says Rollins, “go over there and find a place to hide and eat it and make sure the crumbs were off my face. That’s how up against it we were at certain times.”

Sometimes they’d saunter into a local Mexican restaurant and buy a soda. “Then you’d wait for a family to get up and just grab the little kid’s tostada that he couldn’t finish and take it back to your plate before anyone noticed, because if anyone saw you, you would really bum them out and you’d get thrown out,” says Rollins. “That’s not the way I was raised. I was raised [with] clean white underwear, three square meals, a bed with Charlie Brown blankets, total middle-class upbringing. So all this was new. Scamming on chicks for a hamburger—we would go to Oki Dogs, hit on punker chicks, and say, ‘Hey, we’re poor, feed us.’ We’d get Valley Girl punkers to feed us. And you’d hang out all night waiting for that plate of french fries.

“The thing that kept everyone living this pretty torturous lifestyle is the music was that good,” says Rollins, “and we knew it. At the end of the day, we had no money, we were scruffy, we stunk, the van stunk, everyone was against us. But you’d hear that music and know, oh yeah, we fuckin’ rule.”

Even though they hadn’t yet found a replacement for Dukowski, they were anxious to record their next album—the new slow, metallic Black Flag just couldn’t wait to be born any longer. So Ginn, as “Dale Nixon,” played bass on My War himself, often practicing with the hyperactive Stevenson for eight hours a day, just to teach him how to play slowly and let the rhythm, as Ginn puts it, “ooze out.” “He wasn’t used to playing that slow,” says Ginn. “I guess nobody was.”

My War inverts the punk-to–Black Sabbath ratio of Damaged—this time Sabbath’s leaden gloom and doom predominates, albeit pumped up with a powerful shot of punk vitriol and testosterone. The sound got much more metallic and sludgy, with Ginn anchoring the music with bottom-heavy bass-and-guitar formations. Topped off with some serious jazz fusion influences, My War sometimes comes off like the Mahavishnu Orchestra after a bad day on the chain gang.

Much of the material was strong, but because the band was solely a studio entity, there’s a frustrating lack of ensemble feeling to the tracks; in particular, Rollins’s vocals and Ginn’s leads sound disconnected from everything else. Then there was Ginn’s relentless perfectionism in the studio, which may well be what drained the spark out of many of Black Flag’s later recordings. “He was never willing to just let the performance be,” says Spot, who coproduced the album. “And frankly, I think that’s where he screwed up.” Accordingly, the band’s best recordings from the later period are the live ones, Live’84 and 1985’s Who’s Got the 10½?

My War boiled hardcore angst down to a wall of self-hatred so densely constructed that it could never fall; on “Three Nights” Rollins compares his life to a piece of shit stuck to his shoe, railing, “And I’ve been grinding that stink into the dirt / For a long time now.” But sometimes the lyrics were beside the point—on the title track, Rollins’s bloodcurdling screams and disturbingly animalistic roars speak volumes.

To most listeners, the music had lost the energy and wit of before—Rollins bellows anguished speeches, not the searing, direct poetry of the past. The labored chord progressions and clunky verbiage seem like shackles purposely attached to the band in order to see if they can still run with the weight. For the most part, they could—the playing is ferocious and the band often builds up quite a head of steam only to hit the brick wall of an awkward chord or tempo change. But any momentum My War achieves is stopped cold by a trio of unbearably slow six-minute-plus songs on side two. Although Ginn wrote the lyrics, “Scream” sums up Rollins’s artistic raison d’être in a mere four lines: “I might be a big baby / But I’ll scream in your ear / ’Til I find out / Just what it is I am doing here.” The song ends with Rollins howling like someone being flayed alive.