STARTING BACK IN ’83, STARTED SEEING THINGS DIFFERENTLY

HARDCORE WASN’T DOING IT FOR ME NO MORE STARTED SMOKING POT

I THOUGHT THINGS SOUNDED BETTER SLOW

—SEBADOH, “GIMME INDIE ROCK”

Dinosaur Jr was one of the first, biggest, and best bands among the second generation of indie kids, the ones who took Black Flag and Minor Threat for granted, a generation for whom the Seventies, not the Sixties, was the nostalgic ideal. Their music continued a retrograde stylistic shift in the American underground that the Replacements and other bands had begun: renouncing the antihistorical tendencies of hardcore and fully embracing the music that everyone had grown up on. In particular, Dinosaur singer-guitarist J Mascis achieved the unthinkable in underground rock—he brought back the extended guitar solo.

Dinosaur Jr had nothing to do with regionality, making a statement about indie credibility, or even speaking to a specific community. It was simply about creating good rock music. Even Mascis seemed removed from the feelings he was conveying in the music, which was ironic since he’d come up through hardcore, that most engaged of genres. But while he’d embraced the intensity, he’d abandoned the sensibility of hardcore. Throwing in the twin bogeymen of the underground, classic rock and the navel-gazing singer-songwriter sensibility, made Dinosaur Jr’s music acceptable to a much broader range of people, people who were a little more complacent and less radicalized than the hardcore and post-hardcore types.

Dinosaur also represented a continuing shift on a professional level, too. By the time they came along, the indie underground didn’t have to be do-it-yourself anymore—there were booking agents and road managers and publicists at a band’s disposal, particularly if the band was on SST, which hit its commercial peak in the Dinosaur era.

Rare was a label like Dischord or Twin/Tone that could survive on a steady diet of local bands. Instead, indie labels that stayed alive did so by diversifying. No one had done this better than SST, which by the late Eighties dominated the indie landscape with a roster that also included bands like Screaming Trees, Volcano Suns, All (on the SST subsidiary Cruz), Soundgarden, Meat Puppets, Sonic Youth, fIREHOSE, Bad Brains, Das Damen, and Negativland.

SST would use its power and experience to break Dinosaur Jr. SST worked Dinosaur’s singles to college radio just like “real” record companies, instead of encouraging stations to choose various album cuts. But in the end, if Dinosaur Jr’s songs had been mediocre, SST could have done only so much. As it turned out, Dinosaur’s music was awfully good; it also reached precisely the right audience. The band and college radio developed a symbiotic relationship: Dinosaur thrived on college radio and college radio thrived on making underground stars out of bands like Dinosaur.

The classic rock influences, the extreme volume, the band’s so-called “slacker” style, even their quiet verse/loud catchy chorus formula would soon be imitated and finessed into a full-fledged cultural phenomenon.

Joseph Mascis Jr. grew up in affluent Amherst, Massachusetts, essentially a company town for the area’s famed Five Colleges and a bastion of touchy-feely post-hippieism. Joseph, better known as J, was the son of a successful dentist and a homemaker. He says his parents were “really uptight and not very affectionate,” and, consequently, young J grew up somewhat aloof and self-absorbed. All the furniture in his room was arranged to create a wall around his bed, and there he’d lie for hours, listening to music. Green plastic curtains covered the windows, suffusing the room with an emerald light, and the floor was literally covered with stuffed animals and records. “I was a weird kid,” Mascis acknowledges. “It made people uncomfortable sometimes.”

Mascis had taken a few guitar lessons in fifth grade but quickly switched to drums and played in the school jazz band for years. He was a voracious music listener, exploring the Beatles and the Beach Boys by age ten, then moving into standard hard rock like Deep Purple and Aerosmith. His older brother introduced Mascis to classic rock like Eric Clapton, Neil Young, Creedence, and Mountain, but by eighth grade, he says, “I was strictly Stones.” Then he discovered hardcore. “I didn’t listen to anything else for a while,” Mascis says. “Didn’t understand how anyone else could.”

Lou Barlow and his family moved from a moribund auto industry town in Michigan to blue-collar Westfield, Massachusetts, when he was twelve. “It’s more of a metal kind of town,” Mascis says of Westfield. “It’s like Wayne’s World. I can see Lou getting beat up in high school a lot.” The introverted Barlow found it difficult to make a whole new set of friends. “I retreated into my room and that was it,” he says. “I never came out.” Barlow caught the punk rock bug after hearing the Dead Kennedys on one of the many college radio stations in the area. After that, “I just listened to the radio all the time,” Barlow says. “My grades plummeted—well, they were down there anyway—and I didn’t have any friends.”

Soon after picking up the guitar, Barlow met fellow punk fan Scott Helland at Westfield High; they jammed in Barlow’s attic accompanied by a friend on pots and pans. Soon they put up an ad at Northampton’s redoubtable Main Street Records: “Drummer wanted to play really fast. Influences: Black Flag, Minor Threat.”

J Mascis answered the ad and his dad drove him down to Westfield in the family station wagon for an audition. Barlow was awed the moment Mascis walked in the door. “He had this crazy haircut,” says Barlow. “He’d cut pieces of hair out of his head—there were bald spots in his hair. He had dandruff and he had sleepy stuff in his eyes. Everything ‘sucked,’ which was, like, amazing. I was like, ‘Oh my god, he’s too cool!’ ”

And best of all, “he wailed,” Barlow recalls. Mascis convinced them also to induct his Amherst chum Charlie Nakajima, who sported a Sid Vicious–style lock and chain around his neck. They called the quartet Deep Wound and Mascis’s mom soon knitted him a sweater with a red puddle on the chest with the band name on it. They began playing local hardcore shows at VFW halls and the like—someone would rent a PA, an established national band would headline, and a handful of local bands would pile onto the bill.

Deep Wound went on to play a few shows in Boston, opening for the F.U.’s, D.O.A., MDC, and S.S.D. (It is unknown if they ever played with a band whose name was not composed of initials.) Even though Deep Wound didn’t boast much besides sheer velocity, the band managed to get some national notice in a brief (if comically generic) mention in Maximumrocknroll—“Deep Wound are a hardcore band who ‘are mostly concerned with the struggles of youth in society.’ ”

Barlow and Mascis quickly became good friends. “It was almost romantic, I guess—it’s got that overtone,” says their mutual friend Jon Fetler, Deep Wound’s “manager.” “It was these two talented kids finding each other.” And yet they barely knew each other. “He didn’t say much so I didn’t really know anything about him particularly,” says Mascis. “But when he would talk, it would always be quotes from fanzines…. I would be like, ‘Didn’t I just read that in your room?’ ”

Mascis was hardly more communicative. He spoke very slowly, if at all; he always seemed to be in a daze. People consistently assumed he was a pothead, but he’d been straight edge since his midteens. “I think it’s just my general way of being,” says Mascis. “Everyone always thought I was stoned ever since I can remember. Didn’t talk that much. Perma-stoned.”

Class differences within the band sometimes threatened their laconic friendship. “[Mascis and Nakajima] were from Amherst, they went to school with Uma Thurman and all these professors’ kids,” says Barlow. When Barlow wrote a song called “Pressures,” “a very ‘things are all coming at me and nothing seems real’ kind of song,” says Barlow, they made him change the title to “Lou’s Anxiety Song” just to distance themselves from the unsophisticated sentiment.

A friend pitched in some money to record an EP for Boston’s short-lived Radio Beat label. “It was terrifying—total red light fever,” says Barlow. “We played our songs way too fast. There wasn’t really much of a cohesion in the sound, but we tried.” Steve Albini, in a Matter review, said the EP “alternates between really cool inventive hardball and generic thrashola garbage,” although he felt it was mostly the latter.

Mascis had picked up the guitar again and gradually taken over song-writing duties from Helland and Barlow on the grounds that their material wasn’t “hooky” enough. Although he was still the band’s drummer, he insisted on playing guitar on the EP’s “Video Prick,” festooning this minute and a half of standard hardcore thrash with flashy guitar licks of the “widdly-diddly” variety. Even amidst the EP’s shoddy production, it was evident that J Mascis was one hotshot guitar player.

Conflict fanzine publisher Gerard Cosloy had become a big Deep Wound fan while promoting various hardcore shows in Boston. The evening Cosloy moved into his dorm room at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, he went to a hardcore show in nearby Greenfield and bumped into Mascis, who was also just starting at U. Mass. The two kindred spirits became fast friends. “J was definitely a different sort of individual,” remembers Cosloy. “He was sort of quiet, but when he had something to say it was usually something very, very funny and usually something very biting. He was pretty hard on people. Very hard on people…. Especially for people in the punk rock scene, there was this whole sense that ‘Hey, we’re all part of the same thing, we should all be friends! Hey brother!’ J did not really give off that vibe.”

Mascis cut quite a figure on campus. He wore rings on all his fingers and hippie-style necklaces and moussed up his hair into an arty thicket like his hero, Nick Cave of the Birthday Party. “He had huge fuckin’ hair,” Cosloy recalls, “like stick-your-finger-in-the-socket-type hair.” Mascis made a particularly unusual impression during his visits to the school cafeteria. “J would walk over to the table carrying this mountainous plate of food and proceed to sit there and not even really eat it—he’d just begin to organize it in different patterns and shapes,” says Cosloy. “People would be sort of staring, like, ‘What the fuck?’ I mean, it was hard not to be impressed. You just sort of knew you were dealing with a visionary.”

Cosloy often mentioned Mascis in Conflict stories—“He was fascinated with J’s whole thing and he wrote about it really well,” says Barlow—and featured two Deep Wound tracks on his Western Mass.–centric Bands that Could Be God compilation. Cosloy began managing Deep Wound and started introducing Mascis to American indie bands like True West, the Neats, and the Dream Syndicate; Mascis in turn was introducing these bands to Barlow, but they also dug the hyperkinetic stomp of bands like Motörhead, Venom, and Metallica. “We loved speed metal,” said Barlow, “and we loved wimpy-jangly stuff.

“Once hardcore homogenized into this scene and there’s all these bands with the same kind of chunky sound,” says Barlow, “that’s when we all just sort of went, ‘Fuck it.’ ” Just as important, the music was simply not a good fit with such introspective kids. “Hardcore was not a very personal music to me,” Barlow admitted. “I loved hardcore, but I felt like I wasn’t powerful enough and didn’t have enough of an edge to really make it,” he added. “I felt like a wanna-be the whole time.”

Soon they were delving into the Replacements, Black Sabbath, and Neil Young. It was still mostly aggressive music, but it was slower. “We had sex,” Mascis explained. “You lose the thrashing drive after sex.” And since Deep Wound was nothing but “the thrashing drive,” they called it quits in the summer of ’84, just before Mascis’s sophomore year at the University of Massachusetts.

Cosloy had dropped out of U. Mass. after one semester to move to New York and run Homestead Records. The two kept in touch, and Cosloy promised that if Mascis were to make a record, he’d put it out, whatever it was. “Gerard really did give J something to shoot for,” says Barlow. “That was pretty cool, because that gave J free rein to just absolutely redefine what he wanted to do with music.”

Mascis had been quietly writing songs on his own and eventually played some for Barlow. “They were fucking brilliant,” says Barlow. “They were so far beyond. I was still into two-chord songs and basic stuff like ‘I’m so sad.’ While I was really into my own little tragedy, J was operating in this whole other panorama.” Mascis had somehow incorporated all the music he’d ever listened to—the melodiousness of the Beach Boys, the gnarled stomp of Black Sabbath, the folky underpinnings of Creedence and Neil Young, the Cure’s catchy mope-pop. “Something just clicked with him and he did it,” says Barlow, still marveling. “It was a totally genius little idea.” Within a year Mascis had gone from writing standard-issue hardcore to composing music that had strong melodies, gorgeous chords, and dramatic dynamic shifts. “And he’s playing all this amazing guitar,” says Barlow. “I was like, ‘Bluhhhhhhh.’ ”

Barlow gladly accepted Mascis’s invitation to play bass and took a job at a nursing home so he could buy equipment. He had played guitar and sung in Deep Wound, but he was now content to take any role. “I really accepted my service to his songs,” he says. “Being a bass player can be a great role. I was very keenly aware of how powerful it was. I was very optimistic and very into it.”

Soon Mascis enlisted frontman Nakajima and Nakajima’s high school buddy Emmett Jefferson “Patrick” Murphy III, better known as Murph, on drums. Mascis had also been listening to George Jones, Hank Williams, and Dolly Parton, and the music had rubbed off on him. “Ear-bleeding country,” says Mascis. “That was the concept behind the band.”

Murph had played in a local hardcore band called All White Jury, but his roots were in prog rock and fusion bands like the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Rush, King Crimson, and especially Frank Zappa. He hailed from the well-to-do New York suburb of Greenwich, Connecticut; his father was a professor at U. Mass. Murph had some doubts about the group; a self-described “hippie punk,” he was pretty seriously into partying, something the straight edge Mascis and Barlow turned up their noses at. “They always thought I was a pot-smoking jerk,” says Murph. “They totally had that righteous, fascist attitude. I used to laugh at them and say, ‘Wow, you guys are really uptight to be so secular in your thinking.’ ” But Nakajima, also a stoner, convinced him that it was two against two and it would balance out. And all the while Barlow continued to worry that as the working-class Westfield kid, he was the odd man out. “Oh, they were fuckin’ snotty as hell,” says Barlow. “People from Amherst were assholes.” “It was really tense and weird,” says Murph. “But we couldn’t deny that we could play together.”

They called the new band Mogo, after a book in Mascis’s mother’s vast collection of romance novels, and played their first show on Amherst Common in the first week of September ’84. The stage was within earshot of the local police station, and out of nowhere Nakajima began spouting a punk anticop rant into the microphone. Mascis was appalled. He also didn’t like the fact that Nakajima regularly got stoned for practice, and the next day he broke up the band. Then a few days later he called Murph and Barlow and asked them to form a new band, a trio, without Nakajima. “I was kind of like too wimpy to kick him out, exactly,” Mascis admits. “Communicating with people has been a constant problem in the band.”

Mascis decided to do the singing himself, with Barlow taking the vocal on a few numbers. Barlow took the job very seriously; he would go out for a jog every day and sing the lyrics as he went, then come home and practice playing the songs on bass.

This time, they called the band Dinosaur. Dinosaurs were just beginning to enjoy one of their periodic revivals in the public imagination, and besides, the word fit their music to a T: “He was also playing tons of leads and we were listening to a lot of old Sixties and Seventies heavy rock,” says Barlow, “so it just seemed really appropriate.”

Locally the band wasn’t noted for much besides its ear-splitting volume. “The one sort of statement that J had was, ‘We’re going to be really fuckin’ loud,’ ” says Barlow. “And he was very serious about that. He was very serious about being excruciatingly loud.”

According to Mascis, the reason for the volume wasn’t power madness or better distortion. “After playing drums, guitar seemed so wimpy in comparison—I was trying to get more of the same feeling out of the guitar as playing drums,” Mascis explains. “That’s why I tried to have it get louder and quieter with pedals and stuff—it was hard to get it to have any dynamics like drumming. I was trying to get the air coming off the speakers to hit me in the back, to feel playing as much as hear it.”

As a result, it was hard to tell exactly how the songs really sounded, even to the people in the band. “I could never really hear anything [J] was playing because he played way too loud,” says Barlow. Barlow would have to wait until the band was in the studio to hear the true beauty of the songs’ construction.

The band’s audiences couldn’t fathom the intense volume either. “We ran into a lot of problems playing early on,” says Mascis, “because if you have no fans and you’re really loud, no one wants to deal with you. The clubs are like, ‘What are you doing? Get out!’ We got banned from every club in Northampton.” Dinosaur even had trouble when they later traveled to Boston to open for Homestead bands like Volcano Suns and Salem 66. One soundman actually threw beer bottles at the band—afterward, recalls Mascis, “we were just sitting there driving home, saying, ‘Why are we in a band again?’ We just were driven to do it for some reason, I don’t know why. Just because we had nothing better to do.”

Mascis took Cosloy up on his offer and the band recorded an album for about $500 with a guy who ran the PA for local hardcore shows and had an eight-track studio in his house in the woods outside of Northampton. Musically the album was all over the place, incorporating elements of the Cure, R.E.M., the Feelies, Scratch Acid, and Sonic Youth, not to mention SST bands like Hüsker Dü and the Meat Puppets and their hardcore-country fusion. “It was its own bizarre hybrid,” says Cosloy. “This was definitely music that hardcore punk was the foundation for, but there were more classic influences that turned it into something completely different. It wasn’t exactly pop, it wasn’t exactly punk rock—it was completely its own thing.”

But in a way, it was very punk rock, and not just in the way the rhythm section’s bludgeoning force was so clearly derived from hardcore. “The most punk rock thing about J’s stuff was how much he mixed all his influences,” says Barlow. “He was playing new wave guitar next to heavy metal guitar next to crazy Hendrix leads next to weird PiL single note things. He threw all that stuff together. That was probably the most punk rock thing about it.”

Mascis’s whiny low-key drawl, the polar opposite of hardcore’s boot-camp bark, provided an evocative contrast to Dinosaur’s roiling music. Mascis traces his quasi-southern twang back to John Fogerty and Mick Jagger, both of whom grew up even farther from Dixie than Mascis did. But while his vocal phrasing may have had roots in Stones songs like “Dead Flowers” and “Country Honk,” Mascis’s voice itself more closely resembled Neil Young’s, and the comparisons came early and often and indeed never stopped. “I definitely like the Stones more than Neil Young,” Mascis reveals. “That got annoying, being compared all the time.”

And the comparison probably didn’t help the band, either. Indie rock was becoming very circumscribed—if it didn’t hang on an imaginary laundry line between R.E.M. and the Replacements, few people wanted to hear about it. “People’s initial reaction to them,” says Cosloy, “was, ‘What the fuck is this?’ ”

Dinosaur’s self-titled debut didn’t make much of a splash commercially, selling but fifteen hundred copies in its first year. The larger rock publications and influential critics completely ignored it, although not for lack of trying on Cosloy’s part. He tirelessly championed the record, buttonholing press, radio, and whoever else would listen. But most people thought Dinosaur was a joke. “There were people who literally laughed at me,” Cosloy says. “I remember [Village Voice music editor] Doug Simmons, any time he tried to bring up the fact that Homestead was a flop label, that it would never get anywhere, he’d say, ‘What do you guys have? Dinosaur?’ That was the example of the loser band on the label.”

A small flock of fanzine writers and bands did recognize Dinosaur’s greatness. Boston’s Salem 66 gave the band some opening slots, and Cosloy got Dinosaur some New York shows, which Barlow would drive the band to in his parents’ station wagon. On one such jaunt, Dinosaur opened for Big Black at a sparsely attended show at Maxwell’s. After sound check soundman Ira Kaplan (guitarist in a new band called Yo La Tengo) begged them to turn down. “You guys have really good songs,” said Kaplan, visibly frustrated. “You really should turn down, you can’t hear anything you’re doing!” It only made the band dig in their heels more.

The members of Sonic Youth caught the show but didn’t much care for what they saw. But a few months later they caught Dinosaur at Folk City. The first song began quietly enough, but then the band suddenly erupted in such an overwhelming blast of volume that Thurston Moore felt himself pinned to the back wall. The set ended a few songs later when, after playing an epic solo, Mascis fell back against his amp and slid to the floor in an exhausted heap. This time Sonic Youth walked up to Mascis afterward and declared themselves Dinosaur fans.

Barlow was a little bewildered by the attentions of one of his favorite bands. “It was so weird to have Thurston and Kim showing up at shows, going, ‘Oh, you guys are really great!’ ” says Barlow. “We’re like, ‘What? How could the coolest band in the world like us?’ ”

Mascis had no problem with it at all. That summer he took a bag full of canned tuna and Hi-C down to New York and house-sat Gordon and Moore’s apartment on Eldridge Street while they were on tour. Barlow and Murph stayed up in Massachusetts and practiced together. “That was the only time I could hear what Murph was playing, because J played so loud,” says Barlow. “So me and Murph just practiced together to lock on, which helped the band immeasurably. [J] never seemed to appreciate it, but that’s what we did. Me and Murph just locked on.”

Dinosaur still had not toured, until Sonic Youth, who had just released Evol, invited them on a two-week stint of colleges and clubs in the Northeast and northern Midwest in September ’86. Even without extensive road experience, Dinosaur was a jaw-dropping live act. “There was nothing like them at that point,” says Lee Ranaldo. “They had nothing to lose and everything to gain and they were going for it every night.”

The two bands became quite friendly; they’d often eat breakfast together out on the road, and Mascis would partake of his usual morning meal—Jell-O and whipped cream, cut up and stirred until it was a gelatinous slurry. On the last show of the tour, in Buffalo, Dinosaur played Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” with Ranaldo on vocals, then followed it up with an epic jam.

Mascis, Murph, and Barlow were in great spirits on the ride home. As they were driving back into Northampton, someone slipped in a tape of Evol. Mascis turned to Barlow and said, “Man, this is really weird, I feel like I’m going to cry.”

“Me, too!” said Barlow. “We just toured with our favorite band!”

“We were kind of naive but so happy,” says Barlow. “ ‘Wow, man, we just toured with the coolest fuckin’ band in the world! They’re the coolest. And they like us. And we don’t even know why!’ ”

The band recorded three songs for their next album at a sixteen-track basement studio in Holyoke, then recorded the rest of the album with Sonic Youth engineer Wharton Tiers at Fun City Studios in New York. Murph and Barlow played as hard as they possibly could, while Mascis practically crooned over the turmoil. It was a perfect metaphor for Mascis himself—the placid eye of a storm he himself had created.

Mascis was very specific about what he wanted Murph to play. “When I write songs, the drums are always included as part of the song,” Mascis says. “The melody, the drums—that’s the song to me.” Mascis was a powerful drummer himself, and this began to sow feelings of resentment and inadequacy in Murph. “J controlled Murph’s every drumbeat,” said Barlow. “And Murph could not handle that. Murph wanted to kill J for the longest time…. He kept saying, ‘It may be your scene, but I can’t deal with J. The guy’s a fucking Nazi.’ ” Barlow tried to placate Murph by assuring him that Dinosaur was such a great band that it was worth putting up with all the unpleasantness.

Between Mascis’s seeming apathy and Murph’s bitterness, Barlow felt like he was the only one in the band who thought they were anything special. “Maybe because I was the only one who was getting high a lot,” he says. “We played the same set a lot and the same songs the same way and that really lends itself to getting high after a while and really feeling it, being really into it. And just having visions during the set, like whoa, pure power—savage, raw power.”

Although the music was delivered with brutality, it also harbored catchy, serene, positively life-affirming melodies that routinely attained a kind of forlorn grandeur. “J was an amazing, amazing songwriter whose songs really touched me in a way that a lot of material from that period didn’t,” says Lee Ranaldo. “Black Flag or a lot of the bands that were popular from that period had songs that you really loved, but they didn’t touch you in a personal, emotional way the way that a lot of J’s early stuff did.”

Moreover, the music was crammed with absolutely incredible guitar playing. Solo after solo was rich with style, technique, and melodic invention. In the process, Mascis became the first American indie rock guitar hero. His epic soloing fell right in with the perennial tastes of his peers—children of affluent parentage, the kind who drive their parents’ old BMW off to genteel party schools in New England like Hampshire College and go skiing up in Vermont or out in Vail. These folks had favored the likes of, well, dinosaur bands like the Grateful Dead and their ilk since time immemorial. They were complacent, even bored, and their musical tastes reflected that anomie (and the fact that they had a little extra money to buy pot). J Mascis was one they could finally call their own.

Mascis used pedals, and lots of them—wah-wah, distortion, flanger, volume. This was unheard of in punk rock—only hippies played wah-wah pedals! It was the next step from Hüsker Dü’s wall of sound, but while Bob Mould also used distortion and pedals, he used them to create a constant sonic veil that the listener would have to penetrate; Mascis deployed them more strategically, often shifting suddenly from a pensive verse to a huge, soaringly melodic chorus. That technique would provide the blueprint for early Nineties alternative rock.

Barlow contributed two songs to the second album. Cowed by Mascis’s songwriting prowess, he worked on “Lose” for months before getting up the nerve to show it to the band. His other contribution, “Poledo,” is a sound collage made completely on his own with a portable recorder and a pair of cheap mikes, a hint of things to come.

Gerard Cosloy was smitten with the entire album. “I was absolutely certain that record was going to change everything for them,” he says, “that that record would completely turn everything inside out, that they would go from being this maligned, hated band to being the coolest band on the planet.” And this, thought Cosloy, was the record that would silence the naysayers and finally put Homestead Records on the map.

Cosloy was awaiting the master tape and artwork when Mascis called with stunning news: They had decided to release the album on SST, not Homestead. Mascis assured a dumbstruck Cosloy that it was purely a business decision and nothing personal, but Cosloy wasn’t having it. “There was no way I couldn’t take it personally,” says Cosloy. “That was one of my favorite bands on earth. I felt like I worked incredibly hard for them, maybe the results weren’t so visible at that particular moment, but I felt like I’d really put my ass on the line for them on many occasions, and this was a really, really shitty way of splitting up. I didn’t take it very well. I was pretty fuckin’ angry about it and probably still am…. I just wish he could have done it a little differently. Yeah, that was pretty fuckin’ cold.”

Mascis says he had been reluctant to sign the two-album deal Homestead owner Barry Tenebaum was insisting on—“I really was not into being bound to anything at that point,” says Mascis, “like, loans and all that kind of thing freaked me out”—but Cosloy says Homestead would gladly have done the album as a one-off. “There’s no way we would have not put that record out,” says Cosloy.

While the two parties had been haggling, Dinosaur’s fairy godparents Sonic Youth had sent a tape of the new album to Greg Ginn at SST.

SST flipped over the record. “The stoners at the label loved the guitar,” Barlow explains. After all, heavy music was making a comeback, largely under the aegis of SST; Black Flag had released the sludge-metal-punk landmark My War, and everybody at the label was openly worshiping Black Sabbath for the first time since they were in junior high. And Dinosaur had simply always wanted to be on the label. As Mascis noted, “We wanted to be on SST since we were like fifteen years old, but it just seemed, like, totally out of reach.”

Abandoning Cosloy and Homestead didn’t come without a price, though. “I wasn’t really friends with Gerard after that,” says Mascis. “So that was a bummer, blowing off Gerard. But we wanted to be on SST anyway. It was a casualty of our ruthless record business.”

And yet even Cosloy admits the choice was obvious. “SST was the label everybody wanted to be on,” he says. “Everyone’s favorite bands were on the label; SST was funnier and cooler and it also had the machinery. It was in the place to do a lot of damage whereas Homestead was just me and Craig [Marks], but mostly me. We were not really prepared to go after things. We didn’t have the financing or the support. At SST the people who were running the company were the people in the bands that believed in it. The people who owned Homestead aren’t very comfortable with musicians and think of them as weasels trying to scam money off them. There’s no real way to compare.”

Unfortunately for Barlow and Murph, the contract Mascis signed with SST was structured so that only he received royalty checks from the label. “I had nothing to say about it,” says Barlow. “I thought he deserved it, actually. But selling records was not how we made our money at all—we were making money by being on tour. It had nothing to do with how many records we sold. That was completely foreign to us.”

So it was Mascis’s responsibility to dole out payment to the other two. And Barlow claims he neglected that responsibility. “J’s a real prime, stinking red asshole—that guy is the cheapest bastard,” Barlow says. “He does not get how Murph and I helped him get anywhere that he was. He could not have done that without us. He didn’t see how we were all integral.”

After recording the album, Mascis moved to New York and left his bandmates behind, and the alignments within the band began to change. Barlow now joined Murph in feeling profoundly alienated from Mascis. “I realized there was no way I’d know what was going on in his head,” said Barlow. “It was really bad. He’s a really, really, really uptight person, and the whole time he comes off as being mellow.”

MASCIS, MURPH, AND BARLOW IN AN EARLY SST PROMO PHOTO. NOTE MASCIS’S OLD “DEEP WOUND” SWEATER.

JENS JURGENSEN

Barlow felt bandmates should be close friends, but Mascis was utterly uninterested in that kind of intimacy. “J was one person who just seemed to think that was absolutely nowhere in the whole realm of what was going on,” says Barlow. “He just had nothing to say, yet he had everything to say. That was really quite a puzzle for a while. It really drove his music.

“It was really frustrating,” Barlow says of the alienation between him and Mascis. “It was kind of weirdly heartbreaking.”

Barlow had been spending more and more time at home smoking pot and recording his own songs. “That’s where I started to discover that I had an ego,” says Barlow. “I just became so involved with writing my own songs and really getting into my own sound of things. Just getting totally self-involved. It was pretty great. So when I played for Dinosaur, I was able to play for Dinosaur—do my thing and be quiet.” In the Boston area, early pressings of You’re Living All Over Me came with a tape by Barlow titled Weed Forestin’. It was under the name Sebadoh, a nonsense word Barlow sometimes sang on his home recordings.

“He put out the Sebadoh record and then it was like the door shut—‘I’m not going to contribute anything [to Dinosaur],’ ” says Mascis. “That was always a bummer.” Mascis says he would have welcomed more participation from Barlow, but Barlow says he was both intimidated by Mascis’s songwriting and frustrated by his bandmate’s inscrutable demeanor. In response, Barlow suppressed his own wishes and became an almost literally silent partner in Dinosaur. “I figured out a way to be myself despite being in the band,” says Barlow. “I was super passive-aggressive.”

“We both did that a lot,” says Murph. “But that causes tension. You can’t do that without feeling a certain amount of resentment and negative energy.”

Mascis’s insularity was getting to Murph as well. “J’s way of maybe saying thank you or acknowledging something was so subtle that I wouldn’t see it,” says Murph. “And so I thought he was just being a dick, he wasn’t even acknowledging the effort I’m putting into trying to execute his work. That was a big thing for me.”

And yet Mascis could exert a powerful effect on his bandmates. “J, just for the longest time, if he saw somebody socially having fun or doing something that he wasn’t able to do, he would probably try to put a damper on you and just bum you out or say something negative to the other person so they would see you in a more negative light,” says Murph. “That was the major part of it, J being such a control freak and just not letting up.”

But when a show went well, Murph explains, “and you really felt like you had executed something as a band—really pulled something off—there would be those really short moments of true glory where we would all feel like, ‘Wow, this is worth it.’ But it was very fleeting and it would always come back down to reality. For me, that taste of euphoria would make it worthwhile.”

“There were few bands that could blow people away like that,” adds their friend Jon Fetler. “Dinosaur was one of the ones where people would come back after the show and say, ‘Man, you blew my circuits.’ ”

Barlow and Mascis were an odd match from the start—Barlow was the type of person who needed to pick over his feelings like an archaeologist at a dig; he needed a lot of feedback and encouragement and deeply wanted Mascis’s approval, whereas Mascis cruised through life unquestioningly and was maddeningly self-sufficient. Barlow was skittish, tense, insecure; Mascis didn’t seem to care about anything whatsoever, and as the band’s singer, guitarist, and songwriter, he called the shots.

All that pain was manifested on their second album, You’re Living All Over Me, in the lyrics, in the music, even in the title. “All this struggling that we’d been doing since 1985,” said Barlow, “bouncing off each other and having no clue, not being friends, not knowing if anybody liked our band, not knowing why we’re playing really loud everywhere and being really obnoxious, and all of a sudden everything was channeled into this one record—this is the reason why, this is it.”

It was amazing how Dinosaur turned one of rock’s traditional equations on its head. The volume and noise didn’t symbolize power; it just created huge mountains of sound around the desolate emotions outlined in the lyrics. Mascis’s vocals, cool and collected amidst the chaos, suggested resignation and withdrawal. It was, as one critic put it, a powerful sound that didn’t suggest power.

Song titles like “Sludgefeast” and “Tarpit” certainly bespoke a consistency of vision, and indeed You’re Living All Over Me had an overall murkiness that lent the band a mystique. When the master tape of You’re Living All Over Me arrived at SST, the label’s production manager promptly panicked because the meter was “pinning,” meaning the level on the tape was so high that it was distorting. But Mascis confirmed that that was the way he wanted it to sound. (The group reasoned that since an electric guitar sounded better with distortion on it, a whole distorted record would be even better.) On top of it, Mascis sang like he had marbles in his mouth, while his guitar effects garbled what he was playing. The music was dense and heavy; it was like a pond one could never see the bottom of, so it never grew tiresome to listen to.

Mascis insists that most of the lyrics are about people’s responses to him—nobody was sure if he was oblivious, aloof, or just shy. “A lot of people had intense reactions toward me because I guess I was so blank,” he says. “I was intense but not giving back anything—not normal, like other people would act. And that freaked people out sometimes.” Still, it’s easy to feel that Mascis was writing not about others but, scathingly, about himself: on the debut album’s “Severed Lips,” Mascis drawls, “I never try that much / ’Cause I’m scared of feeling”; “Got to connect with you, girl / But forget how,” he whines on “Sludgefeast,” from You’re Living All Over Me. Countless other songs outline alienation and an inability to connect with another person.

Mascis’s lyrics took on new meaning for Barlow when he began connecting them with his bandmate’s interior life. “I started to see his songs as probably his only noble act as a human being,” Barlow says, “to describe this bizarre ambivalence that was floating around.”

With their buddy Jon Fetler along for the ride, the dysfunctional band began a U.S. tour in June ’87 to promote You’re Living All Over Me. Unfortunately, SST missed the release date and the record didn’t appear in stores until the band had reached California. But minuscule turnouts weren’t the half of it—the band’s frictions hit a hellish peak.

Right off the bat, their clunker ’76 Dodge van broke down somewhere in Connecticut, about an hour and a half into the tour. And that was the least of their problems. As Fetler wrote in his diary, “Band tensions somewhat high. Murph feeling disgruntled, undervalued. Seems like it’s building—he wants to quit after Europe tour or before if he hits J. He keeps saying, ‘I’m gonna pop him, man.’ ” And it was still only the first day of the tour.

The simple fact was that these were three neurotic young men barely twenty-one years old, all cooped up in a van and living on $5 a day. Murph’s genteel Greenwich upbringing didn’t stand him in good stead when it came to the rigors of the road, and he grumbled often about the conditions. In such close quarters, small personal tics began to loom large. “The guy chewed like a cow,” says Barlow of Mascis. “Loudly.” Barlow had his own irritating quirks. “I would put things in my mouth,” he says, “just random things, and chew on them.” This led to the infamous Cookie Monster episode. “I bought this Cookie Monster doll on the tour, and I looked in the van once and Lou was there sucking on its eyeball,” says Mascis. “Something about that disturbed me to my core. I couldn’t handle it. I think I had to throw the thing out. It was weird.”

Another of Barlow’s schticks sprang from his insecurity about where he stood with Mascis. He’d deliberately do something obnoxious and then when someone pointed out that it was “annoying,” he’d claim he didn’t know what the word meant. “He’s going [makes loud chewing sound] some weird annoying sound for, like, an hour and you’re like, ‘Lou, shut up!’ ” says Mascis. “And he’s like, ‘What?’ I didn’t understand how he could not know what ‘annoying’ meant in the first place and how that meant that we didn’t like him or we’re not his friends because we’re annoyed by him…. That was one of our bizarre things on the road.

“Murph and Lou would fight a lot, too, which was hilarious,” Mascis continues. “I just remember sitting in the van—the argument would just be like, ‘Murph, maaaaan!’ ‘But, Lou, maaaaan!’ ‘But, Murph, maaaaan!’ Just like that—for half an hour. Lou had no real ability to listen at that point. Murph would say something and Lou would just be saying the same thing, as if he’d never heard anything Murph said. And Murph was trying, but he’s weird, too.”

But Mascis was no better. “The whole close quarters thing really freaked him out, it really did,” says Barlow, “far more than he even knew.” Rightly or wrongly, Barlow felt Mascis’s anxiety might have had something to do with homophobia. “I thought so,” says Barlow. “I wrote quite a few songs about it.” (“J did have a penchant for just the most disgusting, ass-raping put-downs,” says Fetler. “That just peppered our banter.”)

“At the time, I was twenty and basically of indeterminate sexual preference, and it was one of those weird times when people did a lot of hypothesizing about whether someone was gay or not,” says Barlow. “There was that going on with Murph a bit and then with me, of course, because I had never had a girlfriend or whatever and chose to put everything in my mouth.”

The band’s suffocating tensions did fuel some great shows, even when hardly anybody showed up. “Some of these shows were just super because there’d be six kids that would be right up front,” says Fetler. “And then about three other couples talking in the back. That was it. But for the kids that were there, that record, You’re Living All Over Me, was such a pure thing for them.”

After a show in Phoenix, Murph took the wheel for the overnight drive through the southwestern desert to L.A. while Mascis, Barlow, and Fetler slumbered in the back. Suddenly there was a huge bump as the van ran off the road. “We were all up at the same time in a flash, realizing that we almost died,” says Fetler. Terrified, they asked Murph what happened. “And Murph looks around,” says Fetler, “and says, ‘Well, I consciously decided to fall asleep.’ ” According to Fetler, Murph had been “experimenting with extrasensory driving techniques,” he explained. “I was trying to feel the road, man.” (Murph denies the whole thing.)

When they finally arrived in L.A., they were welcomed by the enthusiastic SST staff. Fetler’s diary records that they were “greeted by a heavyset, longhaired, wild-eyed fellow who exclaimed, ‘Dinosaur! Way cool, dudes!’ ” You’re Living All Over Me was playing on the office stereo; the receptionist was even wearing a Dinosaur T-shirt, the first the band had ever seen. They all went over to Chuck Dukowski’s house and watched a Lydia Lunch film. It was a good morale booster after the ordeal of the past two weeks. But SST’s local clout was given the lie that night when they played a show in a strip mall in Orange County and drew not one paying customer.

After San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle, they were on the home stretch of the tour when the van blew a gasket in Mountain Home, Idaho. It would take several days for replacement parts to arrive, so the band set up camp in a motel, just killing time, stewing in their own juices.

“I remember one day in Kentucky Fried Chicken just ripping Lou apart for an hour or something,” says Mascis. “That was a big turning point. He was really devastated.” It’s not something Mascis is proud of today. “I feel bad about it,” he admits. “I was an asshole a lot of the time when I was younger.”

After that incident Barlow began accumulating a mental file of the slights Mascis threw his way but never actually confronted his bandmate on them. “I just totally took this martyr role,” Barlow says. “ ‘OK, you don’t like me, well, I’ll just try to be as inconspicuous as possible.’ And I made sure that I didn’t put things in my mouth, and I made sure that I just played my parts.” Barlow says Murph and Mascis would barely deign to break down equipment after shows, so he began to do it. Then he says he started to do more than his fair share of driving as well. “I just totally involved myself in just being the martyr,” says Barlow. “I was totally passive-aggressive.”

Murph’s own moment came one night when the four of them were in their motel room, watching TV. Barlow had been insisting on arranging their mattresses in a row on the floor; Murph wanted to stay as far away from his bandmates as possible. “I was getting really uptight about this, and I could tell those guys were all laughing at me,” says Murph. “They thought, ‘This is so funny, Murph is taking this so seriously.’ They didn’t realize I was just, like, freaking. Or they probably did realize it and thought it was funny anyway. That’s when I cracked.”

Mascis tossed some offhand barb at Murph. “And Murph just yells at him, ‘You should be raped by a bald black man!’ ” says Barlow. “And J goes, ‘And that would be you, Murph?’ ” With wicked precision, the remark hit on both Murph’s sexual insecurities and the fact that his hairline was prematurely receding. “And Murph,” says Barlow, “just had a total breakdown.”

Murph hurled a table, a suitcase, and a lamp across the room and began crying and saying, “I can’t take it, I just can’t take it!” “And it was such a dramatic burst of violence and energy that it caused everyone to just go, ‘Whoa…,’ ” says Fetler. Hours later Murph was still weeping and pacing around, smoking a cigarette to calm his nerves; Mascis was sound asleep in bed.

Barlow had read enough of the rock & roll canon to know that some of the most powerful bands—the Who, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones—had tumultuous internal lives. Mascis was aware of the effect the tension had on the music, too. “That’s why a lot of people liked us, because we were a psychodrama onstage,” he says. “It’s like a circus kind of show, which might be fun to watch but not necessarily fun to be in the middle of.”

At times it seemed as if the assault was not just from within. Soon after the initial pressings of You’re Living All Over Me were shipped, a band featuring former members of San Francisco acid casualty groups such as Big Brother and the Holding Company and Country Joe and the Fish laid claim to the name “the Dinosaurs.” Mascis renamed his band Dinosaur Jr, no comma or period.

Barlow’s nonexistent romantic life was decisively jump-started by one of his own songs. “ ‘Poledo’ was probably my biggest attempt at meeting a girl through music, to totally express myself in a song,” Barlow says. “I believe in music in that way—if you want something to happen, you write a song about it.” It worked beyond Barlow’s wildest expectations.

To Kathleen Billus, music director of Smith College’s radio station, “Poledo” “felt like the answer to my dreams,” she wrote in a later memoir, “like what I’d been wanting in a song my whole life, something I was aching for but wouldn’t be able to describe.” When Barlow did an interview at the Smith radio station in September ’87, she jumped at the chance to meet him. They hit it off and soon became a couple.

But the romance had to get put on hold while Dinosaur Jr did a four-week European tour in October ’87. Whatever image Mascis had been cultivating, it came to fruition on that tour. The British press loved his lackadaisical manner, his tasteful mishmash of influences, his offhand wisdom. (Pushed by an English interviewer to name something he was scared of, Mascis was at a loss for words but eventually answered that he was scared of all the butter the British put on their food.)

“Who do you listen to?” asked Melody Maker’s David Stubbs. “… Uh… everybody,” Mascis replied. “Now, this may not seem like much of an answer,” wrote Stubbs. “This is not Quote of the Year and wants for the delicious aphoristic quality which we so enjoy in an Oscar Wilde or a Nietzsche. But stark print cannot do justice to its catatonic deadweight, more eloquent than any Pete Burns rant, the sprawl of the drawl, the great mental cloud which attempts to conceive of the great swathes of rock history in which Dinosaur are soaked. The pause that precedes this answer is like the death of the word.”

They were flattered that these Americans liked English bands such as the Jesus and Mary Chain and the Cure. The English press, whipped to a froth by the exotic brutishness of Blast First bands such as Sonic Youth, the Butthole Surfers, and Big Black, had found a new object for their love/hate relationship with American culture. Mascis was some sort of idiot savant worthy of equal parts reverence and condescension. To Americans, the band was readily recognizable as a typical bunch of apathetic Northeast ski bums; to the British, they were like the wildmen of Borneo.

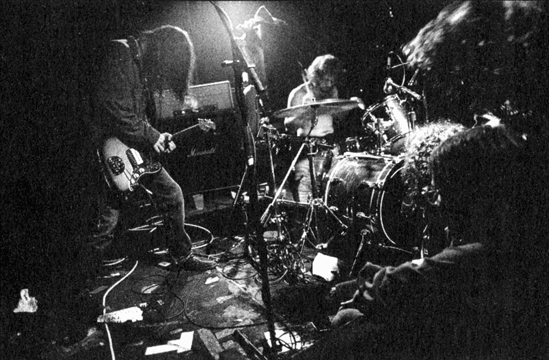

DINOSAUR JR IN CONCERT AT THE CENTRAL TAVERN IN SEATTLE, 1989.

CHARLES PETERSON

And after Dinosaur’s tour, a whole wave of English groups, dubbed “shoegazer bands,” sprang up in their wake, playing folk chords through phalanxes of effects pedals to make swirling, deafening music; they uniformly adopted a nonchalant demeanor and paid lip service to Neil Young and Dinosaur Jr.

Meanwhile Barlow was retreating more and more. “I was afraid of stepping on anybody’s toes,” said Barlow. “I felt really bad about it and didn’t want to perpetuate the weirdness. I just wanted to play bass.” But Mascis has a different take. “Lou couldn’t really have a conversation,” he claims. “He could just say what was on his mind, but he couldn’t process things coming back. It was just really strange.”

But very little was coming back to Barlow from Mascis anyway. “We never communicated, really,” says Mascis. “Didn’t really know how, I guess. Too young. We hadn’t learned that yet.”

As Gerard Cosloy had predicted, You’re Living All Over Me was a big hit in the indie world. Throughout the country little pockets of fans had been slowly but surely spreading the word about Dinosaur. “It built up to a critical mass of people,” says Cosloy, “disaffected hardcore fans, indie rock fans who wanted something that wasn’t so fuckin’ bland, people who were into noisier and more experimental things who were beginning to open up to things that were a bit more melodic—this whole new consortium of bands, writers, DJs, musicians, freaks, whatever, all began to come together. Dinosaur was the band that they came together around.”

But the more successful Dinosaur became, the more that success displaced their creativity. For better or worse, soundmen weren’t throwing bottles at them anymore. They rarely practiced and professed to have little interest in advancing their career. “We’re totally lazy,” Barlow admitted. They’d realized their longtime dream of being on SST but had set no bearings beyond that.

“It’s different to function without a goal than with a goal,” says Mascis. “It was, like, ‘Well, we’re still around. Now what?’ ” The band never did regain that sense of purpose, although they did have a powerful incentive to keep going. “I knew I didn’t want to get a job,” Mascis says with a laugh. “That was always motivating me.”

Success was the worst thing that could have happened to the band. “It seemed to kind of kill J’s motivation,” says Barlow. “Once the shows became packed, it just became another thing J had to do as opposed to what it was early on. He just made it clear that he really couldn’t be bothered and he’d rather just go back to sleep—if it was all really up to him, he wouldn’t be doing it.”

So while Barlow was so idealistic about music that he wrote a song specifically to get himself a girlfriend, Mascis just wrote songs because that’s what he was supposed to do. “And that was why his songs were so fuckin’ amazing and why he had such an amazing grasp of the guitar,” says Barlow. “He wasn’t idealistic, he was just insanely pragmatic.

“Once he knew that people demanded something in particular,” Barlow says, “he just sort of figured out a way he could live up to those demands but not really give too much of himself.”

Mascis told Spin’s Erik Davis that he found the guitar to be a “wimpy instrument.” “You really don’t like guitar?” Davis asked.

“No,” Mascis replied.

“Why do you do it?”

“Dunno.”

It’s no wonder that the songs of Dinosaur’s third album, Bug, didn’t quite have the spark of You’re Living All Over Me. The songs didn’t come as easily to Mascis, and it didn’t help that they were in a hurry to capitalize on all the acclaim they’d received over the previous year or so. Mascis says he had been hoping that Barlow would take up the song-writing slack, but Barlow was in full retreat and deeply immersed in his homemade Sebadoh tapes, which Cosloy was now releasing on Homestead. Despite his prolific Sebadoh output, Barlow wrote no songs for Bug. “I realized that if I wasn’t going to be able to interact personally with the people in the band, there’s no way I’m going to be able to give them songs I really care about,” said Barlow. “If I had tried to interact with J and tried to write songs, the band would have broken up a lot sooner.

“I was really afraid of him,” adds Barlow. “After a while my fear of him just exceeded everything else and I couldn’t even play him my songs anymore. It kind of devolved to that point.”

“We were just in a bad state,” says Mascis. “The band was going down already.”

Many of the songs on Bug were recorded not long after they were written. Barlow and Murph were only minimally involved in the sessions. Mascis told them exactly what to play, they’d make slight modifications, then record their parts and leave Mascis to finish the rest.

The band tried on a lot of different ideas on the first album, as if they were seeing which ones fit the best; on the second album it all jelled. By Bug it was starting to become a formula. “It’s the album I’m least happy with of anything I’ve done,” says Mascis.

But Mascis’s appraisal of the album is probably colored by the experience of making it—despite some filler, Bug is a powerful record. “Freak Scene,” the album’s single, was classic Dinosaur, probably because it so directly encapsulated the band’s roiling inner life. One passage alternates a guitar sound like a garbage disposal with bursts of glinting twang; there’s a completely winning melody delivered in Mascis’s trademark laconic style and not one but two memorable, molten guitar solos. On top of all that, the lyrics seem to be about Mascis and Barlow’s dysfunctional relationship: “The weirdness flows between us,” Mascis yowls, “anyone can tell to see us.” The song was a big college radio hit and seemed to be blasting out of every dorm room in the country that year.

“Yeah We Know” finds the band in thunderingly good form—Murph’s pounding, musical drumming powers one of Mascis’s best songs to date. Perhaps the song draws some of its vehemence from the fact that, as Mascis now admits, it’s about the band itself—“Bottled up, stored away,” Mascis yowls, “Always ready to give way.” But the album reserves its most harrowing psychodrama for the closing “Don’t,” a dirge-metal noise orgy with Barlow screaming, “Why, why don’t you like me?” for five minutes straight. It was a bit ironic, to say the least, for Mascis to have Barlow sing such words. “That was kind of twisted,” Mascis admits. “ ‘All right Lou, sing this: “Why don’t you like me?” over and over again.’ That was kind of a demented thing.”

Barlow sang the song with such violence that he began coughing up blood afterward.

In October ’88 Dinosaur Jr did another European tour, once again with Fetler in tow as confidant and referee. In Holland they stayed with their European booking agent. Barlow had been annoying Murph for some reason now lost to the sands of time, but that was nothing unusual. “There were always little bitter bickerings going on,” says Fetler. “That was part of the chatter—‘blah-blah-blah fuck you blah-blah-blah.’ ” But tensions were apparently higher than anyone realized.

That night, when Barlow went into Murph and Fetler’s room to get an extra blanket, Murph started growling ferociously in his sleep, then stood up—still sleeping—and started heading for Barlow. Mascis saw the whole thing. “I just remember Murph sleepwalking, getting up like some primitive animal, this caged animal, going at Lou like he was going to kill him,” says Mascis. “I was standing behind Lou watching Murph come at him in his boxer shorts. I was thinking, ‘Either Murph’s going to wake up or he’s going to kill Lou.’ And I was waiting to see what happened. And right when he got there, he woke up.”

“It was very heavy,” wrote Fetler in his diary, “and kind of weird.”

And yet the tour was hardly a complete nightmare. In Europe the halls were huge, the audiences enthusiastic, the accommodations top-notch. But the band’s internal strife was plain to see, especially as the tour culminated, in a string of U.K. dates with Rapeman. “They were near disintegration at that point, and the drag-ass depression hung over them like a bad smell,” recalls Rapeman’s Steve Albini. Of course, Rapeman didn’t help Dinosaur’s morale by stink-bombing the band’s van, dressing rooms, hotel rooms, sound checks, and even meals.

The British press had fastened itself even harder on to the idea that Dinosaur was a bunch of sleepy-headed apathetic types—Mascis’s vocals were “a sculpted yawn,” the band were “titans of torpor,” “Numbosaurus Wrecked,” “a cult of non-personality.” One writer compared Mascis to the “giant three-toed sloth.”

One of the few British journalists who got it right was Sounds’ Roy Wilkinson, who actually made the journey to Amherst to see the place that had birthed Dinosaur. Said Murph, “We have to have been affected by where we came from. Around here it’s the easy life. There’s no harsh things—no poverty, no crime…. And people don’t struggle that hard to live.” Dinosaur, then, seemed to answer a very American question: What happens when you get everything you ever wanted?

Dinosaur came to represent “slackers,” then a new term for the particularly aimless subset branded by the media as Generation X, the group of kids who had grown up in relatively comfortable, uncontroversial times, kids whose parents, as Kim Gordon once put it, “created a world they couldn’t afford to live in.” Slackers didn’t care about much except music, which they consumed with discernment and gusto. Mascis, with his listless demeanor and guitar heroics, became something of a slacker poster boy, even though he and the band rejected the mantle wholeheartedly. After all, he and Barlow had grown up on committed, hardworking bands like Black Flag, Minor Threat, and the Minutemen. “The whole thing at that time was to be like you didn’t give a shit about stuff,” says Barlow. “I was always a step behind that. I never really could get into it.”

Barlow had moved in with his girlfriend Billus in her room in the Friedman dorm complex at U. Mass. in the spring of ’88. The relationship gave him confidence and self-esteem, enough to drop his subservient relationship to Mascis. “I just started speaking my mind and not giving a shit what he thought,” says Barlow. “I could just see it really bugging him, but I really enjoyed it.” And that’s when it really started to go downhill.

“He didn’t really talk until he got his girlfriend,” says Mascis, “and somehow that jump-started his ego, and he went from ‘I am Lou, I am nothing’ to ‘I am the greatest.’ He just went ffffft, just flipped the scales. And then he started talking a lot. And then I was realizing from a lot of the things he was saying, ‘Hmmm, maybe I don’t like Lou.’ I’d never heard him talk before so I didn’t really know what was going on in his head. And then when you hear what’s he’s talking about, it was like, ‘Hmmm, interesting—I’m not really into that.’ ”

Starting with the Bug tour, Barlow occasionally abandoned his usual parts and indulged in what Fetler calls “sonic dronings,” Sonic Youth–inspired playing that wasn’t anywhere near what he’d played on the record. Barlow had been playing tape collages between songs for a year or so, surely borrowing the idea straight from Sonic Youth; but now he was setting them off during the songs. It may well have been Barlow’s way of asserting himself after being so subdued; at any rate, Mascis took the unsolicited modification of his music as a personal affront.

It had all come to a head at an early ’88 show at a small club in Naugatuck, Connecticut. The place was far from packed and the band wasn’t playing very well. They were halfway through “Severed Lips” when Barlow began making feedback with his bass instead of playing the usual part.

“Lou is sitting on the drum riser, just making noise through every song—this one note—and just trying to goad us, taunting us, basically,” says Mascis. “And I’m playing and I’m like, ‘I think Murph’s going to beat up Lou.’ And it goes on a little bit more and I’m thinking, ‘Yup, this is going to be bad, Murph’s going to beat up Lou.’ And I keep playing and I keep thinking that, and finally, I think, ‘Huh, I guess Murph’s not going to beat up Lou. I guess I’ll have to do it.’ ”

Mascis rushed across the stage and tried to hit Barlow with his guitar. Barlow raised his bass like a shield while Mascis bashed away at him repeatedly. (“It made a pretty good sound,” Mascis recalls somewhat fondly.) After a few failed bashes, Mascis stalked offstage yelling, “I can’t take it! I can’t take it!” Barlow called after him, “Can’t take what, J? Asshole!” and raised his fists in triumph. “I got really psyched, like psychotically happy, and just went, ‘Yes!’ ” says Barlow. “I felt like he’d proved to me that he actually had feelings. He never would react to anything at all, ever.”

“I remember just sitting there at my drum set going, ‘OK, this is my perfect opportunity to pummel both of these guys,’ ” says Murph. “But instead I just walked off.” Barlow followed Mascis and Murph backstage and assured them that he didn’t mean anything by the feedback. The band went out again, played what was surely a fearsome cover of “Minor Threat” and drove home in silence. It was the beginning of the end.

In one fall of ’88 interview, Mascis acknowledged the band’s overwhelming internal strife but admitted he was just too lazy to fire anybody: “I just know I’ll always be in a band,” he said, “so I’d rather just have one and keep going rather than have to start another one.”

But in July ’89 Mascis decided Barlow had to go. He and Murph went over to Barlow’s house to deliver the news. Tellingly, it was the first time either of them had ever been there. Mascis had a knack for delegating unpleasant tasks, so Murph did most of the talking while Mascis hovered in the doorway. “I would be the spokesman for J, and I would kind of present bad news or pave the way,” says Murph. “He was just into having other people execute his dirty work. J is very smart that way—he gets a great network of people to suffer the blow.”

But somehow, even after an hour of talking, they hadn’t managed to convey the idea that they were firing Barlow. Instead, Barlow had the impression that the band was breaking up entirely. “I said, ‘OK, that’s cool, see you guys later,’ ” says Barlow. “And they left.”

“We did kind of let him believe that,” Murph admits. “That was the evil thing. J and I were just spineless.” In fact, they had already booked a tour of Australia and arranged for Northwest punk mainstay Donna Dresch, who had played for a time with the Screaming Trees, to fly in from Washington State to replace Barlow. They were even thinking about signing with Warner Brothers.

A day or so later, Barlow heard about all this from a friend. Distraught, he called up Mascis, and Murph and Mascis dropped by Barlow’s house again. “We had everything out,” says Mascis. “I didn’t say anything. I was just sitting there, observing. Murph was doing all the talking. We couldn’t deal with each other at all.”

The next day Murph and Mascis were sitting in their friend Megan Jasper’s kitchen, talking about Barlow and regretting that they hadn’t been more straightforward with him when suddenly Barlow burst in the door. “You fucking assholes!” Barlow screamed. “I can’t believe you didn’t have the balls to tell me to my face! I have to find out on the street!”

“All of the disgust that I was holding in for all those years just came out,” says Barlow. “It was pretty rough to deal with, not so much because of what they had done to me, but just the role I had chosen to play and all of the stuff that I had chosen to let build up inside of me and never really deal with. I had to sort through a lot of that and I was really extremely angry.” After some more scolding, Barlow left without further incident.

Mascis served as some kind of perverse muse for a whole series of Sebadoh songs. “I got a lot of hatred out just by writing songs,” Barlow says. “I just wanted to get under his skin. I wanted to wheedle my way in, in some way that was just not anything like what J was doing. So he was a real inspiration in a lot of ways.”

Most of the screeds came out on singles, including one titled “Asshole”; the sleeve even has the Sebadoh name set in the same typeface as the Dinosaur logo. Barlow coyly acknowledged his target by including a snippet from the film Say Anything. “This song is about Joe,” says a girl’s voice, “and all my songs are about Joe.”

Barlow insisted he was obsessed not with Mascis but with the issues of control the situation represented. The relationships within Dinosaur, he held, were a metaphor for a larger truth about the human condition. “That’s a weird little kink in human nature that I couldn’t figure out,” Barlow says. “This idea of negative charisma and the way people tend to project things onto people and also control, the myriad ways people can control other people. Sometimes it has nothing to do with actually telling them what to do. It has to do with totally vibing people out. And there was so much of that going on.”

Barlow’s screeds alienated many Dinosaur fans, most of whom bought Mascis’s image as a benign, gifted narcoleptic. But Mascis himself says he didn’t care about Barlow’s attacks. “It’s just more Lou to me,” he says wearily. “I’ve had a lot of Lou in my life.”

The rift between Mascis and Barlow was enthusiastically covered by the press. “It makes me sick that I spent six or seven years putting my heart and soul into that band,” Barlow told Cut zine in 1990. “They’re sleazebag snob pigs like no one I have met in my entire life. J’s always been an asshole.” It was a bit of a one-sided feud, though, since Mascis rarely fired back, not out of his usual avoidance of communication, but because he’d honored a request by Barlow that he not talk about him to the press.

When Mascis was asked in a Melody Maker interview what the band planned to do now that Barlow had gone, his reply may have defined the slacker ethos right then and there. “We have no plans for what we want to do next,” he said. “We have no plans about anything, really.”

By the summer of ’90, Dinosaur released a great new single, “The Wagon,” which Melody Maker named one of two Singles of the Week. “Am I allowed two-word reviews?” asked writer Everett True. “Sheer exhilaration!” He went on, of course.

By this time Mascis had decided to move to a major label. “The thing I thought was great about it was they would just pay you on time,” says Mascis. “I like Greg Ginn and stuff, but they wouldn’t pay you. Homestead I didn’t like and they were more just, like, dicks. They didn’t pay and they didn’t care. It was like all these indie labels that are ripping you off are supposed to be better than the major label who won’t rip you off.”

Other than that, Mascis’s reasons for moving to a major are unclear. “It just seemed like the thing to do, I don’t know,” says Mascis. “Just because we could do it. I’m not sure.”

Mascis says he got little grief from the indie cognoscenti for going major label. “It wasn’t that polarized yet,” he says. “It was just kind of this weird thing—‘Wow you’re on a major.’ There were a few bands that did it and stuff, it’s just kind of odd, you’re not really sure what to think of it. I can see now how it’s damaging, after being through it. I didn’t really have any concept.”

Mascis solved his communication issues by playing virtually every instrument on Dinosaur’s 1991 major label debut Green Mind, which won the attentions of commercial radio, the major music magazines, and even MTV.

Meanwhile Barlow had come back into Mascis’s life—terrified that he might go broke now that he wasn’t in Dinosaur, Barlow hired a lawyer and sued Mascis for $10,000 in back royalties. “But I didn’t owe him anything—we hadn’t gotten any money,” says Mascis. “I was really flipped out about that. I thought that was just really a bummer to me. Instead of calling me up and asking me, he just assumed. I’m not sure what was going on with him at the time, but that was really… I don’t know.” But during months of legal wrangling, some money actually did come in and the two settled.

It was the beginning of a rough period for Barlow. Because he was paying a lawyer to recover the money he felt he was owed, Kathleen Billus was supporting him. “And she eventually supported me until she hated me and dumped me,” says Barlow, “for the lawyer that was getting me the money from J! It was just nuts!” (Barlow and Billus soon reconciled and eventually married.)

Barlow was convinced that Dinosaur could have achieved widespread popularity if they’d only preserved their original inspiration. Mascis, he says, deliberately avoided any steps that might have brought the band greater fame. “For him it was, ‘I don’t know if I want to be famous,’ ” says Barlow. “Or ‘I don’t know, I have nothing to say.’ I was, like, ‘What?’ He just got too caught up in it or something. I mean, Jimi Hendrix wasn’t asking himself all these questions, he just fucking did it. And they got off on it. Black Sabbath, any fucking band, they were into music. Why deny it? That just drives me absolutely insane. Isn’t this what it’s all about?”

Shortly after Nevermind was released and immediately began scaling the charts, Barlow bumped into Mascis on the streets of Northampton. “I was like totally high and drunk,” says Barlow, “and I was like, ‘They fucking beat you to it! You could have done it, you asshole, we could have fucking done it!’ ”