5

Which Bonds Are Right for My Portfolio?

Treasuries provide not risk-free return but “return-free risk.”

—Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

Bonds are much different from stocks. They have a more straightforward relationship between price and yield than that of stocks, and are far more sensitive to the effects of inflation. With bonds, price and yield are inversely proportional—every time yields go up, bond prices go down; every time yields go down, bond prices go up. The magnitude of the price increase and decrease is contingent on the duration of the bond: the longer the bond has until it matures, the greater the magnitude of its price movement when interest rates rise or fall.

Thus, long-term bonds will earn the greatest gains when interest rates are falling and shorter-term bonds will earn the least. Bonds come in all duration periods, from one year to thirty years and beyond. There are as many types of bonds as there are durations—the safest bonds (i.e., with the lowest risk) are issued by the U.S. government and the largest U.S. corporations. Traditionally, corporate bonds offer higher yields because they have an implicit default risk, which is based on investors’ assumptions about the company’s ability to repay its debt. Companies with excellent creditworthiness have bonds that are ranked from A to AAA by Moody’s or Standard and Poor’s. Bonds issued by companies that the rating services believe are less likely to be able to repay them are called junk bonds, and have gained in popularity over the last two decades. Junk bonds traditionally pay much higher yields as a consequence of their shaky credit ratings, but they are also the most likely to default on their obligations, leaving the bondholder feeling more like a bag holder.

In this chapter we will be looking specifically at U.S. Treasury bonds and bills, as they offer the closest thing to “riskless” returns that fixed income securities have to offer. We’ll see that the prospects for U.S. Treasuries will be applicable to all bonds or bond funds that you might consider adding to your portfolio. I’ll use a methodology similar to the one used for stocks—first I’ll review the real returns that bonds and T-bills have earned historically, then analyze the returns over rolling twenty-year periods.

Ibbotson defines long-term bonds as those U.S. Treasury bonds with durations of twenty years or more. Intermediate-term bonds—the shortest duration noncallable bonds—have maturities not less than five years, and U.S. T-bills are thirty days in duration. As always, we will only look at real, inflation-adjusted rates of return.

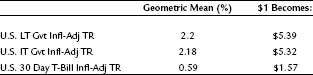

Bonds Offer Modest Returns

The results are fairly horrific—unless you were lucky enough to load up on bonds in September 1981, when interest rates were at their highest levels in U.S. history. Over time, your chances of earning a negative real twenty-year rate of return from long-term U.S. bonds were better than fifty-fifty! Figure 5–1 and table 5–1 show that one dollar invested in 1927 grew to just $5.40 if invested in long-term U.S. bonds, a compound return of 2.2 percent over the seventy-eight years. Investors in U.S. intermediate-term bonds earned virtually the same amount—one dollar invested in 1927 grew to $5.32, a real compound return of 2.18 percent. (This is extremely important, as we’ll see in a few pages.) Investors in T-bills barely managed to stay ahead of inflation—one dollar invested in 1927 grew to just $1.57 at the end of 2004, a real average annual compound return of just 0.59 percent.

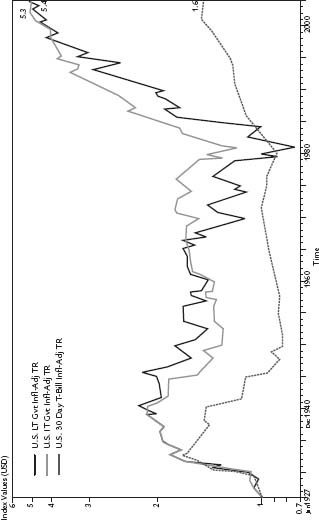

Fifty-three Years Under Water

The real rate of return for long-term bonds and T-bills is directly tied to inflation and regulations that enforced an interest rate ceiling on banks after the Depression. An investor buying long-term bonds or U.S. T-bills in 1931 would have had to wait more than fifty-three years for his investment to make any money at all! Table 5–2 shows the real returns for bonds and bills between 1931 and 1984, and shows that anyone investing one dollar in long-term U.S. Treasuries lost three cents on the value of their dollar investment over the fifty-three years, whereas someone investing in T-bills saw their dollar shrink to just 81 cents! Only those who invested in intermediate-term bonds over the period made money.

TABLE 5–1 REAL RETURNS FOR FIXED-INCOME SECURITIES, JUNE 30, 1927–DECEMBER 31, 2004

FIGURE 5–1 TERMINAL REAL RETURN VALUE OF $1 INVESTED IN 1927

TABLE 5–2 REAL RETURNS FOR FIXED-INCOME INSTRUMENTS OVER 53 YEARS, DECEMBER 31, 1931–DECEMBER 31, 1984

The irony is that investors view U.S. bonds and bills as the safest investment they can make! History shows us that this is completely false. Imagine the exodus from stocks if they had fifty-three-year periods where they lost money—it would be virtually impossible to get anyone to invest in the stock market. What’s more, the twenty-year rolling analysis shows that for a majority of the rolling twenty-year periods, investors in long-term U.S. bonds lost money!

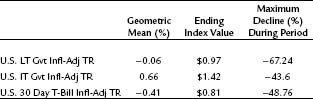

Rolling Twenty-Year Periods

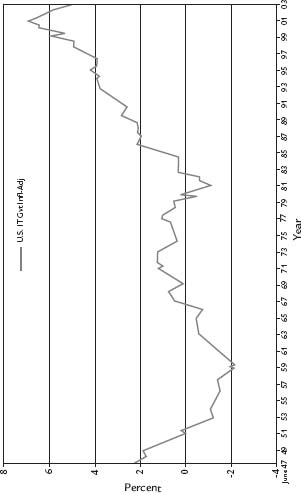

Figure 5–2 shows the rolling twenty-year real rates of return for an investment in long-term U.S. bonds. The best they ever did was a gain of 9.38 percent for the twenty years ending September 2001; the worst was a loss of 3.12 percent for the twenty years ending September 1981. The average twenty-year return for long-term U.S. bonds was a paltry gain of 0.97 percent over all twenty-year periods between 1947 and 2004. Long-term bonds provided investors with negative returns in 402 of the 691 rolling twenty-year periods, or 58 percent of the time! Looking at figure 5–2, we see that the real twenty-year rate of return for long-term U.S. bonds went negative in the early 1950s and stayed under water until 1986! Truly a horrible performance for an instrument viewed as the “safest” investment for conservative investors.

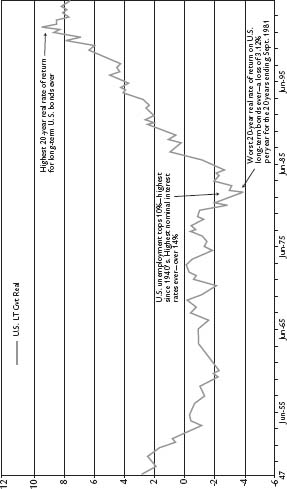

Figures 5–2 and 5–3 also show us that it wasn’t just equity markets that experienced a perfect storm—bonds also saw the best returns that any of us are likely to see again in our lifetimes. In September 1981, the U.S. economy was reeling—runaway inflation and unemployment were destroying its core. Popular movies and books of the era depicted a world in which the United States would lose its economic supremacy to the Japanese as our industrial core decayed. Between 1978 and 1980, OPEC doubled the price of oil, pushing the United States and other industrial countries into the deepest recession since the Depression of the 1930s. U.S. unemployment was above 10 percent, higher than at any time since the 1940s. The nominal yield on long-term bonds topped 14 percent and investor sentiment was nearly as bleak as it had been during the depression. It was truly an act of faith to buy long-term bonds—but investors who did so were richly rewarded over the next twenty years. The U.S. government, particularly the Federal Reserve, finally got its act together. First under the leadership of Paul Volcker and then Alan Greenspan, the Fed broke the back of inflation with a lot of help from “bond market vigilantes” who, after the repeal of regulation Q, a Depression-era law that enforced a ceiling on interest rates, were quite willing to push interest rates to any height to ensure that they would receive a decent real rate of return.

FIGURE 5–2 REAL ROLLING 20-YEAR RATES OF RETURNS, 1947–2004

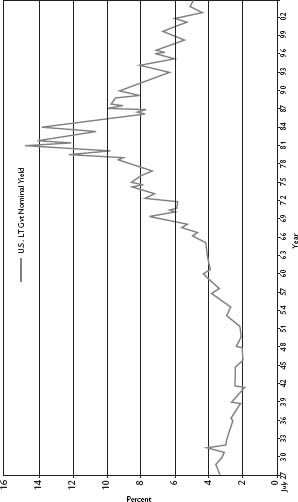

FIGURE 5–3 NOMINAL YIELD FOR U.S. LONG-TERM BONDS, 1927–2004

Intermediate-Term Bonds a Better Bet

While intermediate-term bonds also have many twenty-year periods where they lost money, their odds of making money are considerably higher than those of long-term bonds. Figure 5–4 shows the rolling real twenty-year rate of returns for intermediate-term bonds between 1947 and 2004. The best twenty-year return intermediate-term bonds earned was a real annual return of 6.98 percent for the twenty years ending September 2001; their worst was a loss of 2.13 percent for the twenty years ending December 1959. The average real return for all rolling twenty-year periods was a gain of 1.32 percent.

Unlike long-term bonds, intermediate-term bonds only served up twenty-year losses to investors in 206 of the 691 rolling twenty-year periods, or 30 percent of the time. What’s more, intermediate-term bonds had much lower volatility than long-term bonds while providing virtually the same long-term return and much higher returns over all twenty-year holding periods. In the 691 rolling twenty-year periods, intermediate-term bonds outperform long-term bonds 57 percent of the time. They also have a lower correlation to stocks than long-term bonds—the correlation of long-term bonds with the S&P 500 between June 30, 1927, and December 31, 2004, was 0.16, whereas it was 0.14 for intermediate-term bonds. That means intermediate-term bonds are more likely to provide positive returns when stock prices are declining—analyzing all 919 rolling twelve-month periods between 1927 and 2004, the S&P 500 had negative returns 300 times, or 33 percent of the time. When the S&P 500 had a negative twelve-month return, intermediate-term bonds had positive returns in 173 of the 300 periods, or 58 percent of the time. Long-term bonds provided positive returns in 157 of the 300 periods, or 52 percent of the time.

Finally, when interest rates are rising, intermediate-term bonds are much better performers, since they have much shorter durations and are therefore less subject to duration risk than their longer-term counterparts.

FIGURE 5–4 REAL ROLLING 20-YEAR RATES OF RETURN FOR U.S. INTERMEDIATE-TERM BONDS, 1947–2004

U.S. Treasury Bills

Finally, we will look at the returns from short-term U.S. Treasury bills, which can also be used as proxies for money market funds. Figure 5–4 shows the real returns for all rolling twenty-year periods between 1947 and 2004. The best returns from T-bills were a gain of 2.95 percent per year for the twenty years ending December 2000; the worst returns were a loss of 3.20 percent per year for the twenty years ending April 1952. The average real twenty-year return from T-bills was an anemic 0.13 percent per year over all rolling twenty-year periods.

The loss of 3.2 percent per year for the period between 1932 and 1952 shows that investors cannot rely on T-bills to keep up with inflation. Indeed, in 234 of the 691 rolling twenty-year periods analyzed, T-bills had negative returns. That’s more than one-third of all the twenty-year periods analyzed, and a reminder that “safe” investments can often be anything but. The greatest irony of all is that T-bills show us that making timid choices with our investments can leave us with a portfolio whose purchasing power becomes seriously degraded over time. Clearly, investors need to rethink what is truly risky and what is not. In my opinion, the gravest risk investors face is not short-term volatility but long-term degradation of their purchasing power. Thus, investors must understand that investing in T-bills will at best keep them about even with inflation. At worst it will rob them of purchasing power.

Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS)

We now have a new weapon in our arsenal to use when attempting to forecast the expected real rate of returns of bonds over the next twenty years—inflation protected bonds. Issued for the first time by the U.S. Treasury in 1997, they have gained in popularity over the years. Here’s how the U.S. Treasury’s Web site describes them:

TIPS provide investors with an investment option that protects against the effects of inflation. Like all marketable US Treasury securities, TIPS are backed by the full faith and credit of the US Government. TIPS are available to individual and institutional investors alike.

Interest payments on TIPS are made semi-annually and are linked to the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (CPI-U). The underlying value of the principal grows at the same rate that prices (as measured by CPI-U) rise. When the principal grows, interest payments grow also since interest payments are a fixed percentage of principal. At maturity, if inflation has occurred and increased the value of the underlying security, Treasury pays the owner the higher inflation-adjusted principal. If, however, deflation has occurred and decreased the value of the underlying security, the investor receives the original face value of the security.

Earnings from TIPS are exempt from state and local income taxes just as other US Treasury notes and bonds. TIPS owners pay federal income tax on interest payments in the year they are received and on growth in principal in the year that it occurs.

Thus, the current yield of a ten-or twenty-year TIPS will give you the exact expected rate of return for each duration series if you hold them to maturity. Their day-to-day prices will still fluctuate like other bonds, but if you hold them for their entire duration, you are assured of what your real rate of return will be when the bond matures. As I write this in May of 2005, the ten-year TIPS bond has a yield of 1.57 percent and the twenty-year TIPS a yield of 1.70 percent, making those our effective expected rate of return for bonds for the period ending 2022–2025.

TIPS Are Not Perfect

While the current yields of inflation-protected bonds serve as an ideal proxy for forecasting the long-term expected rate of return for bonds, they are far from perfect investments. First, because you have to pay taxes on Treasury bonds, every time your principal increases to reflect the impact of inflation, the IRS treats the extra value as ordinary income, which is then taxed. Since TIPS protect against inflation by pegging their par values to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) every six months, you could end up paying taxes on phantom income. If the CPI rises 10 percent over the course of six months, for example, a new TIPS bond price would be expected to go from $1,000 to $1,100. That process continues until maturity, so the final value of a TIPS bond can’t actually be known until that time. It’s also possible that TIPS prices can fall if the CPI falls, but they can never go below the original $1,000 mark. Nevertheless, you’re paying taxes along the way.

TIPS are also subject to the same interest rate risk as conventional bonds—if interest rates spike up, the value of your bond will decline and you could face a loss if you don’t hold the bond to its maturity. Finally, TIPS are also an implicit bet that investors have correct expectations for inflation—a conventional Treasury bond, for example, that matures in February of 2015 currently yields 4.13 percent, whereas the TIPS bond that also matures in 2015 yields 1.57 percent. This implies that investors believe inflation will run at 2.56 percent per year through 2015. But what if it doesn’t? If inflation increases one percent per year through 2015, investors in the regular Treasury bond will have done much better than those in the inflation-protected version. Conversely, if inflation comes in much higher than 2.56 percent per year, the investor in TIPS will do vastly better than an investor in a conventional bond.

Creating a Laddered Bond Portfolio

We are currently emerging from one of the longest periods of declining interest rates in U.S. history. In keeping with the perfect storm analogy, investors are unaccustomed to increasing interest rates, but that is precisely what we might be facing over the next twenty years. As the baby boom generation ages and requires additional medical attention government obligations are going to balloon, adding a huge burden to the Medicare and Medicaid programs. After a long increase in U.S. productivity, many analysts now have more modest expectations for continuing productivity gains, which will directly affect the amount of tax revenue the government collects. Altogether, demographics and tax revenue shortfalls point to an environment in which the government will be forced to increase taxes; the rate of return that investors will demand will in all likelihood increase commensurately.

With this being the case, what should fixed income investors do? We’ve already seen that intermediate-term bonds outperform long-term bonds in the majority of twenty-year periods analyzed. In an environment of rising interest rates, the best choices are short-and intermediate-term bonds. And the best way to buy them is in a “laddered” fashion.

A laddered portfolio is built by staggering the durations of the bonds you are buying. If you wanted to keep all durations to a maximum of five years, for example, you would buy one bond that matured in one year, the next in two years, and so on, out to the five-year maximum. As each bond matures, you replace it with one that is farthest out on your duration schedule. The staggered maturities allow you to always have funds available for reinvestment. If rates do rise, you will always be putting money to work in the new, higher-interest bonds. My advice would be to do this until interest rates are at or above their historical average. For the period between 1927 and 2004, the average yield on long-term Treasuries is 5.39 percent and 4.88 percent for intermediate-term Treasuries. Only after rates have gone above these averages should you consider buying longer-term bonds with a duration of ten or more years. Even then, you will still benefit from using a laddered approach.

Chapter Five Highlights

- Bond prices are easy to predict—as rates fall, bond prices increase; as rates rise, bond prices fall. There are a great variety of bonds, but only U.S. Treasury bonds and bills have no default risk.

- Bonds are traditionally viewed as “safe” investments, but the historical data contradicts this. Long-term Treasury bonds have provided negative twenty-year real returns 58 percent of the time for all rolling periods between 1947 and 2004. Over all twenty-year periods analyzed, the average real rate of return for long-term bonds was 0.97 percent per year.

- Intermediate-term bonds have historically done better than long-term bonds in all rolling twenty-year periods analyzed. They provided negative real returns in 33 percent of all rolling twenty-year periods, compared to 58 percent of all twenty-year periods for long-term bonds. They also had a higher average real rate of return of 1.32 percent per year. In addition, they had a lower correlation with the S&P 500 and provided more positive returns when stock returns were negative.

- U.S. Treasury bills provided an anemic real return of 0.13 percent over all rolling twenty-year periods. They provide negative returns over a third of all the twenty-year periods analyzed and should be expected to only keep pace with inflation.

- The real rate of return to long-term bonds reached a historic high of 9.38 percent per year for the twenty years ending in September 2001. This was the result of the high nominal yields in 1981—the highest in a century—and will most likely not happen again in our lifetimes.

- The Treasury now offers inflation-protected bonds known as TIPS. They assure that investors will always earn a real return from their investments; their current yield serves as an excellent guide to what the expected rate of return will be for bonds in the future. Currently, the ten-year TIPS bond has a yield of 1.57 percent and the twenty-year a yield of 1.70 percent. These become my bond forecasts through 2025.

- The best way to invest in bonds during a rising interest rate environment is to create a short-duration laddered portfolio. This allows you to always have money becoming available to invest in a higher yielding bond.