6

Behavioral Economics: Why We Know What Isn’t So

The same thing happened today that happened yesterday, only to different people.

—Walter Winchell

“We have met the enemy and he is us,” claimed Pogo, Walt Kelly’s famous cartoon character. He could have been talking about investors. I have long contended that in the battle for investment success, investors are their own worst enemy. I published my first investment research in 1989 in a paper entitled “Quantitative Models as an Aid in Offsetting Systematic Errors in Decision-Making.” In it, I set out to demonstrate that human beings ultimately determine how stocks are priced. Since we don’t check human nature at the door when entering a stock exchange, I argued that we could learn a great deal from psychological studies that proved that in uncertain situations, our judgment is systematically flawed.

The solution I offered was that investors could make much better decisions by using dispassionate quantitative models, whose efficacy had been proven over long periods of time. My belief then—as now—was that we can only make better financial decisions by circumnavigating our human nature. All too frequently, investors ignore logic and reason. When trying to make good investment decisions, investors fall back on their own worst impulses. Fear, ignorance, greed, and hope conspire to rob us of our ability to make sensible, intelligent decisions about the market. We let our feelings overcome reason and take shortcuts that violate all logic. We live in the here and now—not the past or future. This is our greatest roadblock when trying to make good investment choices. Because today’s information or today’s catchy headlines get filtered through our emotions, we give them the greatest import, giving far too little import to longer spans of time. What the market did today or this week is quite meaningless to long-term investment performance. In his book Behavioral Finance: Insights into Irrational Minds and Markets, James Montier writes:

This is the world of behavioral finance, a world in which human emotions rule, logic has its place, but markets are moved as much by psychological factors as by information from corporate balance sheets….[T]he models of classical finance are fatally flawed. They fail to produce predictions that are even vaguely close to the outcomes we observe in real financial markets…. Of course, now we need some understanding of what causes markets to deviate from their fundamental value. The answer quite simply is human behavior.

Behavioral Finance and Prospect Theory

Behavioral finance is a discipline that has emerged in the last two decades; researchers in this field attempt to explain how emotions and cognitive errors influence investors in the decision-making process. In this chapter, I’ll review their major findings and how they relate to the twenty-year financial cycles we see occurring again and again.

Amos Tversky, a Stanford psychology professor (who died in 1996), along with his colleague Daniel Kahneman, a professor at Princeton University, are generally cited as the fathers of behavioral finance. Tversky and Kahneman pioneered psychological and economic studies that revolutionized the scientific approach to decision making. They ultimately won many prestigious awards and honors, including the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, awarded to Kahneman in 2002.

They called their work prospect theory and argued that when making decisions under uncertainty, people are not cool, rational, and calculating. In a paper published in 1979, they argued that investors placed different weights on financial gains and losses, being much more distressed by prospective losses than pleased by equivalent gains. In one experiment, Tversky and Kahneman offered their subjects two scenarios. In scenario one subjects could choose option A, a 100 percent chance of winning $50, or option B, a 50 percent chance of winning $100 and a 50 percent chance of winning nothing. In scenario two, option A was a 100 percent chance of losing $50, and option B was a 50 percent chance of losing $100 and a 50 percent chance of losing nothing.

Even though the odds were exactly the same in each scenario, Tversky and Kahneman found that an overwhelming majority of their subjects chose option A in scenario one but option B in scenario two. In other words, people are risk-averse when facing gains but risk-seeking when facing potential losses. When Tversky and Kahneman manipulated the odds in each scenario, they found that generally, people consider losses twice as painful as gains, and will take on huge risks to avoid them. Conversely, they will take very little risk when seeking gains. These findings directly contradict a basic rule of traditional economic theory called expected utility theory, which posits that people will always behave rationally and pick the optimum solution when facing a gain or loss.

Tversky and Kahneman replicated these results with a new set of participants who made the same mistakes—leading them to conclude that these errors can be predicted and categorized. Worse news is that even armed with this knowledge, investors keep making the same mistakes over and over again. We are all programmed to believe that while these errors might affect other people, we are personally immune. As Kahneman says, “these are cognitive illusions that will not go away just because we know them.”

Prospect theory directly explains why people sell their winners too soon and hold their losers too long. Historical financial research shows that, in general, winners continue to win and losers continue to lose (for an in-depth discussion of this, see chapter 15 in my earlier book What Works on Wall Street). Yet, because of the way our brains are programmed, when it comes to investment decisions we continually do the opposite of what we should. Prospect theory also explains why investors undervalue investments they perceive as risky and overvalue investments they perceive as certain. Thus, despite the long-term evidence that shows inflation-adjusted T-bills earn almost nothing over long periods of time, investors are far more likely to look at T-bills as the safest investment that they can make.

Fear of Regret

Professors Meir Statman of Santa Clara University and Terry Odean of the University of California at Berkeley have also shown that people are so regretful when a stock they own is losing money that they are reluctant to sell it. In his 1998 paper “Are Investors Reluctant to Realize Their Losses?,” published in the Journal of Finance, Odean analyzed the trading records for ten thousand accounts at a large discount brokerage house. He found a strong tendency among investors to hold losing investments too long and sell winning investments too soon. Odean writes: “These investors demonstrate a strong preference for realizing winners rather than losers. Their behavior does not appear to be motivated by a desire to rebalance portfolios, or to avoid the higher trading costs of low price stocks. Nor is it justified by subsequent portfolio performance.”

Others have hypothesized that the well-established fear of regret is the reason that investors follow the crowd. By doing what everyone else is doing, individual investors can avoid the regret they might feel if they resisted conventional wisdom and wound up being wrong. The market bubble of the late 1990s is a classic example of this: investors were essentially buying stocks of profitless companies, primarily because everyone else was doing it. When it went drastically wrong, well, at least they had a lot of company. As the famous economist John M. Keynes aptly quipped, “people would rather fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally.”

Another basic human instinct is the desire to appear intelligent—no one wants to advocate ideas or investments that are at odds with the collective wisdom of Wall Street. As a result, investors consistently get swept up in prevailing trends, for better or—more often—worse. If you think you are immune, look at your own portfolio. Chances are, in both the past and the present it mirrors the market’s most popular trends.

What’s more, popular trends become self-perpetuating. Optimistic investors are often more than willing to throw money at the fastest-growing segments of the market. This often leads to outright speculation, where capital is too readily provided to unworthy companies. Inevitably, many of these speculative investments fail, setting up a market correction. If prolonged, this downturn leaves investors overly pessimistic and risk-averse. And on it goes.

The Availability Error

Another error investors consistently fall victim to is the availability error. Simply put, people overweight information that is easy to recall. Ease of recall is directly linked to how vivid the information is and how frequently we come into contact with it. Dramatic, colorful, and concrete information is easier to remember and influences the choices we make. Statistics are abstract, boring, and dull. Stories are fun, colorful, and interesting. Which will be easier to remember?

At the top of the bubble, investors were bombarded with colorful, interesting stories of the vast wealth being created in Silicon Valley and other new-economy outposts. CNBC churned out colorful charts of stocks rocketing upward and magazines sang the praises of new-era businessmen. Not to be outdone, Time named Amazon.com’s founder and CEO Jeff Bezos its 2001 “Person of the Year.” In its tribute to Bezos, the magazine said, “It’s a revolution. It kills old economics, it kills old companies, it kills old rules.” And Time wasn’t alone—the glories of the new economy and new-era investments were trumpeted everywhere in the media, making these the most available “facts” for investors. And because people overweight the most available information, the majority of investors based their investment decisions on what turned out to be illusions.

We’re not just susceptible during boom times, either. In the early 1980s investors shunned stocks because of how poorly they had performed over the previous two decades. All the information available to investors at the time indicated that stocks and bonds were the worst investments you could make. In the early 1980s, Howard Ruff’s How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years sat at the top of the national best-seller lists for two years, selling almost 3 million copies and becoming one of the top-selling financial books of all time. His forecast for the 1980s? Gold was headed to over $2,000 an ounce and interest rates were going to exceed 40 percent.

The Halo Effect

Well, you might argue, “I always try to make good investment decisions. I listen to the recommendations of Wall Street’s highly regarded analysts—after all, they make big bucks for a reason.” But do they? Research by money manager David Dreman has shown that for the most part, analysts’ predictions are so far off the mark they are virtually useless. Unfortunately, paying attention to high-profile analysts is also part of our human hard-wiring; it is driven by the halo effect.

In his book Irrationality: Why We Don’t Think Straight! Stuart Sutherland says, “Also related to the availability error is the halo effect. If a person has one salient (available) good trait, his other characteristics are likely to be judged by others as better than they really are.” In other words, we tend to judge others on the prestige of their position or distinction of their employer. When an analyst from a blue-chip investment house offers advice, we are inclined to believe that his or her opinions are much better than our own.

Rather than actually questioning the validity of what he is saying, we endow him with abilities he might not possess. Sutherland cites a fascinating study that proved how pernicious the halo effect can be. In the study, two psychologists proved that the halo effect strongly influenced what the editors at several important journals of psychology were willing to publish. According to Sutherland the two psychologists

selected from each of 12 well-known journals of psychology one published article that had been written by members of one of the 10 most prestigious psychology departments in the US, such as Harvard or Princeton: in consequence, the authors were mostly eminent psychologists. Next, they changed the authors’ names to fictitious ones and their affiliations to those of some imaginary university, such as the Tri-Valley Center for Human Potential. They then went through the articles carefully, and whenever they found a passage that might provide a clue to the real authors, they altered it slightly, while leaving the basic contents unchanged. Each article was then typed and submitted under the imaginary names and affiliations to the very same journal that had originally published it.

Of the 12 journals, only three spotted that they had already published the article. This was a grave lapse of memory on the part of the editors and their referees, but then memory is fallible; however, worse was to come. Eight out of the remaining nine articles, all of which had been previously published, were rejected. Moreover, of the 16 referees and eight editors who looked at these eight papers, every single one stated that the paper they examined did not merit publication. This is surely a startling instance of the availability error. It suggests that in deciding whether an article should be published, referees and editors pay more attention to the authors’ names and to the standing of the institution to which they belong than they do to the scientific work reported.

If the halo effect is this profound in a rigorous setting with academic referees and multiple editors, imagine how it can influence the average investor listening to the advice of a blue-chip stock analyst.

Myopic Loss Aversion and Narrow Framing

Richard Thaler is a professor of economics at the University of Chicago and one of the more prolific authors in the study of behavioral finance. In his paper “Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle,” he and coauthor Shlomo Benartzi argue that investors do not invest their money rationally or with the appropriate time horizons in mind. For example, if a young investor is saving for retirement thirty years from now, he should use that time period as his benchmark for investment returns.

Unfortunately, investors rarely do this. Instead, Thaler and Benartzi found that if investors are in the habit of checking their portfolio every quarter, that becomes their new time horizon. They make choices based on their portfolio’s recent performance rather than focusing on the twenty or thirty years they have until retirement. Thus, our young investor will not be able to make wise choices if he remains myopically focused on the short term. The combination of shortsighted behavior and an aversion to loss helps explain why many people find higher-returning, higher-risk stock funds less attractive than they should.

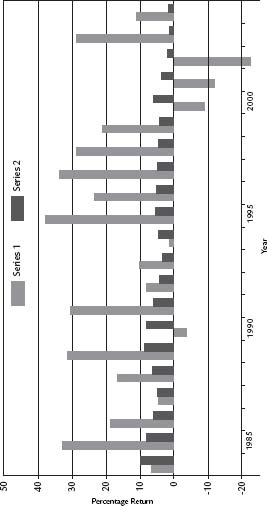

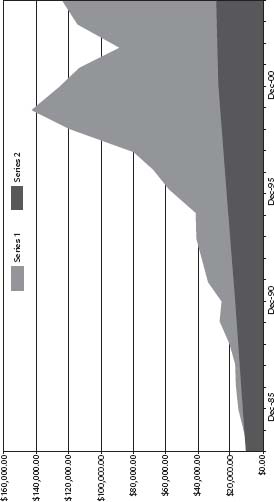

When looking at investment alternatives, how you frame a problem can strongly affect the outcome. I tested this by showing people two graphs, featured in figures 6–1 and 6–2, asking which portfolio was more attractive to them. When presented with the annual returns featured in figure 6–1, most people chose the less volatile portfolio with steady year-in, year-out gains. However, when presented with figure 6–2, showing the cumulative value of $10,000 invested in exactly the same portfolio, most chose the more volatile portfolio that offered higher returns over the long term.

This exercise shows how strongly framing affects us as investors. When we look at the day-to-day or even year-to-year changes in our portfolios, the narrower time frame makes us very risk averse. When we use a broader time frame that only takes final value into account, however, we are far more likely to invest in the portfolio that appears risky in the short term but provides much higher returns over the long term.

Framing and shortsightedness are also the reasons investors prefer stocks that have done very well over the last five years—when they should be doing just the opposite. In a study I conducted for What Works on Wall Street, I looked at the returns of the stocks that had either been the fifty best performers over the last five years or the fifty worst performers. The results showed that an investment in the fifty worst performing stocks from the previous five years trounced an investment in the fifty best performing stocks. One dollar invested in the previous five years’ worst performing stocks on December 31, 1955, grew to $248.12 by the end of 2003, a real annual return of 12.17 percent. The same dollar invested in the previous five years’ best performing stocks grew to only $3.56, a real annual return of just 2.68 percent per year!

These data have also proved true in international markets. In the essay “The Psychology of Underreaction and Overreaction in World Equity Markets,” published in Security Market Imperfections in World Wide Equity Markets, Professor Werner F. M. De Bondt finds the same pattern in ten countries, from Australia to the United Kingdom. De Bondt says: “How valid are expert and amateur predictions of share prices, earnings, etc.? How do people go about making these forecasts? What type of information attracts the most attention? A recurring theme in the literature is the disposition to predict the future based on the recent past. People find it difficult to project anything that is greatly different from the apparent trend—even if over-optimistic forecasts and groundless confidence are the net result.” He also suggests that both winning and losing stocks may simply be reverting to their mean returns.

FIGURE 6–1 NOMINAL ANNUAL RETURNS, TWO DIFFERENT PORTFOLIOS, DECEMBER 31, 1983–DECEMBER 31, 2004

FIGURE 6–2 TERMINAL NOMINAL VALUE OF $10,000 INVESTMENT IN TWO PORTFOLIOS ON DECEMBER 31, 1983

Clearly, the best way to make an investment decision is to study all periods that coincide with your actual investment horizon. If you are forty-five and want to retire at sixty-five, then you should look at all twenty-year periods to make your choices, but human nature makes this highly unlikely. We attach the most importance to the news we read today, and by doing so lose sight of the bigger picture.

Mental Anchoring

Behavioral finance also shows that we use recent prices and news as mental anchors for what price levels or returns are “right.” For example, people have a strong tendency to overweight recent experience, view it as “correct” and then extrapolate it well into the future. This helps explain why investors in the late 1990s believed that large-cap growth and technology stocks were the only game in town. Mental anchoring also traps us into believing that whatever is happening in the market today will continue forever, rather than doing what it always does and returning to its long-term mean. The NASDAQ may not reach 5,000 for years, but for many investors coming of age during the bubble, that is the “right” price that is anchored in their brains.

In a famous 1974 experiment, Tversky and Kahneman showed that you could get people to anchor answers to random numbers. They asked a group of participants to guess how many African countries were members of the United Nations. Before being allowed to guess, however, the psychologists spun a fortune wheel with numbers between 1 and 100. Unbeknownst to the participants, the wheel was rigged to land on either 10 or 65. After the spin, the participants were asked if the actual number of African nations was higher or lower than the number on the wheel, and for their exact guess. The median response from the group that guessed after the wheel landed on 10 was 25; the median guess from the group that guessed after the wheel landed on 65 was 45!

Overconfidence and Hindsight Bias

Each of us, it seems, believes that we are above average. Sadly, this cannot be statistically true. Yet in tests of people’s belief in their own ability (typically people are asked to rank their ability as a driver), virtually everyone puts themselves in the upper 10 to 20 percent! Other surveys show that when you take a random sample of adult males, and ask them to rate themselves on a number of parameters, the first being their ability to get along with others, every single respondent ranked himself in the top 10 percent of the population; and a full 25 percent say they fall in the top 1 percent! Similarly, 70 percent ranked themselves at the top for leadership ability, and only 2 percent felt they were below average leaders. Finally—in an area where self-deception should be difficult—60 percent of males said that they were in the top 20 percent for athletic ability, and only 6 percent said they were below average. We are clearly deluding ourselves.

In his 1997 paper “The Psychology of the Non-Professional Investor,” Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman says: “The biases of judgment and decision making have sometimes been called cognitive illusions. Like visual illusions, the mistakes of intuitive reasoning are not easily eliminated…. Merely learning about illusions does not eliminate them.” Kahneman goes on to say that, like our investors above, the majority of investors are dramatically overconfident and optimistic, prone to an illusion of control where none exists. Kahneman also points out that the reason it is so difficult for investors to correct these false beliefs is because they also suffer from hindsight bias. Kahneman writes that “psychological evidence indicates people can rarely reconstruct, after the fact, what they thought about the probability of an event before it occurred. Most are honestly deceived when they exaggerate their earlier estimate of the probability that the event would occur…. Because of another hindsight bias, events that the best-informed experts did not anticipate often appear almost inevitable after they occur.”

In a famous experiment, a Cornell professor gave his class a quiz at the beginning of the year, asking them to forecast where financial indicators like the Dow Jones Industrial Average, interest rates, and gold prices would be at the end of the year. He put the forecasts away until the end of the term, when he then asked if anyone recalled their forecasts. Most only vaguely recalled the assignment. In this particular year, the Dow had been strong, with falling interest rates and stable inflation. When the professor asked how many thought they had made correct forecasts, virtually every hand in the room went up. However, when the actual forecasts were reviewed, they were all over the map, with many predicting a falling Dow and rising interest rates! Just like the Cornell students, investors frequently deceive themselves into thinking they knew something would happen before it did. In reality, this is rarely true.

Representativeness

We often assume things will come out the way we think they should—stocks with great performance should have great stories driving their gains. Great companies should be great investments; boring companies should be boring investments. In forming subjective judgments people look for familiar patterns, relying on well-worn stereotypes. These mental shortcuts are called heuristics, or mental rules of thumb. In many instances, these mental shortcuts are helpful, but not when it comes to investing. Here, they frequently lead to errors in judgment. We’ve seen, for example, that people largely ignore how frequently something occurs. These odds are called base rates. Base rates are among the most illuminating statistics that exist. They’re just like batting averages. For example, if a town of 100,000 people had 70,000 lawyers and 30,000 librarians, the base rate for lawyers in that town is 70 percent. When used in the stock market, base rates tell you what to expect from a certain class of stocks (e.g., all stocks with high dividend yields) and what that variable generally predicts for the future. But base rates tell you nothing about how each individual member of that class will behave.

Most statistical prediction techniques use base rates. Seventy-five percent of university students with grade point averages above 3.5 go on to do well in graduate school. Smokers are twice as likely to get cancer. Stocks with low price-to-earnings ratios outperform the market 65 percent of the time. The best way to predict the future is to bet with the base rate that is derived from a large sample. Yet numerous studies have found that people make full use of base rate information only when there is a lack of descriptive data. In one example, people are told that out of a sample of 100 people, 70 are lawyers and 30 are engineers. When provided with no additional information and asked to guess the occupation of a randomly selected 10, people use the base rate information, saying all 10 are lawyers, since by doing so they assure themselves of getting the most right.

However, when worthless but descriptive data is added, such as “Dick is a highly motivated thirty-year-old married man who is well liked by his colleagues,” people largely ignore the base rate information in favor of their “feel” for the person. They are certain that their unique insights will help them make a better forecast, even when the additional information is meaningless. We prefer descriptive data to impersonal statistics because it better represents our individual experience. When stereotypical information is added, such as “Dick is thirty years old, married, shows no interest in politics or social issues and likes to spend free time on his many hobbies which include carpentry and mathematical puzzles,” people totally ignore the base rate and bet Dick is an engineer, despite the 70 percent chance that he is a lawyer. One can even jack the base rate for lawyers up to over 90 percent, and people will cling to their stereotypical opinion of an engineer.

Behavioral Finance and the Twenty-Year Money Cycle

Such is the state of Homo economicus—even though we can learn and rationally understand why we make the investing mistakes we do, we are destined to repeat them. We are hard-wired to act the way we do. Neurobiologists are proving this with PET scans of our brains—when making decisions under uncertainty the rational part of the brain is mostly dormant but the emotional part fires away! In his book Mean Markets and Lizard Brains, Terry Burnham says that there are biological causes for irrational financial behavior, and these in turn cause market panics and crashes. We literally are reverting to our “lizard brain” when faced with the emotion-jarring task of investing our money. He points out what a recent study at MIT confirmed—the most successful investors are those who have a system in place to guard against emotional decisions.

Indeed, having a guiding, unemotional system might be the only way to successfully guard against making the same mistakes time and again. As Woody Dorsey says in his book Behavioral Trading: Methods for Measuring Investor Confidence, Expectations, and Market Trends: “What is the difference between hunter-gatherer guys and gals of 40,000 years ago and our contemporary go-getters? Nothing. The competitive urge is basic and perpetual.”

Financial markets have alternated between booms and busts for over two hundred years. Each generation falls prey to the fads, fallacies, enthusiasms, and stories of its era, most often when the market is at or near the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next. The problem is, investors make decisions based on information they learned about as it unfolded—information that proves nearly useless in the market’s next phase. This explains why investors so predictably shun stocks and bonds near market bottoms but buy with abandon near market tops. It seems each generation is amused by the folly of those that preceded it, while remaining totally ignorant of its own.

To understand that our earlier theories of rational human decision-making were fatally flawed, we must pay attention to the actual data and the actual way we make choices. As Maurice Allais, the eminent French economist and winner of the 1988 Nobel Prize for Economics, says, “I have never hesitated to question commonly accepted theories when they appeared to me to be founded on hypotheses which implied consequences incompatible with observed data. Dominant ideas, however erroneous they may be, end up, simply through repetition, by acquiring the quality of established truths which cannot be questioned without confronting the active ostracism of the establishment.”

By ignoring all of the experimental data that has accumulated over the last fifty years, we continually put ourselves in harm’s way, and continue to make exactly the same mistakes, generation after generation. It seems our very humanity is what makes this endless cycle a permanent facet of our investment lives.

Chapter Six Highlights

- Modern portfolio theory contends that investors are rational, dispassionate, and understand the odds. Fifty years of financial evidence and behavioral research contradicts this theory.

- Behavioral finance is a new discipline that attempts to define the way investors actually make choices. Researchers have found that in reality, people regularly violate the basic rules of rational decision-making.

- Behavioral finance research shows that investors are risk-averse when facing gains but risk-seeking when facing losses. Investors also overweight recent information—especially when it is colorful and vivid—and have a strong tendency to follow current market trends.

- Investors face a number of psychological pitfalls. Most of us are guilty of.

- 1. Shortsightedness—our overreliance on short-term data

- 2. Overconfidence—the tendency to rank our own abilities too highly

- 3. Hindsight bias—believing that we know an outcome before it occurs

- 4. Representativeness—seeing things the way we think they “ought” to be.

- Investors’ behavior can often be best described as bipolar. On one hand, they are overly timid, risk-averse, and prone to follow the crowd. On the other hand, they are far too confident and optimistic. The modulation between the two may explain the market’s boom-bust cycle.

- Given the predictability of investors’ behavior—both historically and internationally—it appears to be a fundamental part of human nature. In order to overcome the enemy within, planning and structure are essential to investment success.