February–May 1943

On February 7 The Times carried an editorial titled “War on All Fronts.” It was a play on words. Alongside the “gratifying victories” in Russia and the South Pacific, there were areas still in crisis where arguments went on between allies about the distribution of American resources and reinforcements. The war for resources, continued The Times, could not be solved overnight but required hard thinking about priorities. Moreover, the resources themselves were vulnerable in transit.

The spring of 1943 was full of bad news from the Battle of the Atlantic, a conflict that German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz was determined to fight to the finish. In 1942, 7.8 million tons had been sunk on the high seas, just a little less than the 8 million tons built in American shipyards. The submarine “wolf packs” were restricted now to the so-called Atlantic gap as air cover spread over the ocean. In March large convoys were heavily mauled, but in April Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox announced a sudden fall in sinkings. In May only 160,000 tons of shipping was lost at sea while forty-one German submarines were sunk. Thanks to breaking the German naval codes, the use of long-range aircraft, advanced new radar equipment and naval support groups, the submarine threat was finally defeated. At the end of May Dönitz admitted defeat and withdrew his force. The same month the operation of Allied submarines and aircraft against Axis shipping in the Mediterranean starved Axis forces in Tunisia of resources and oil. The naval war on all fronts had gone the Allied way.

The struggle in North Africa had nevertheless been longer and tougher than expected. For American forces it was a harsh learning environment as they pressed across Northwest Africa toward Tunis. On February 20 Rommel inflicted a sharp blow at the Kasserine Pass, but was unable to exploit the breakthrough once British and American reinforcements arrived. The Times observed that American soldiers had to learn in order to survive. “The Doughboy,” ran one headline, “is, in Turn, Cocky, Scared, Dazed, Damn Mad and Effective.” By mid-April Axis forces were bottled up and, on May 13, 240,000 German and Italian forces surrendered, a larger number than had been captured at Stalingrad. Far away from the action, American forces stationed in the Aleutian Islands began the difficult task, in appalling conditions, of dislodging the small Japanese force from the island of Attu. This was indeed war on all fronts.

The long years of war took their toll on domestic peace. In America there were grumbles about rationing. In April the National Negro Congress called for an end to race discrimination and the right of blacks to be hired for any job. In early May a major strike for higher wages was called in American coal and anthracite mines. The strike rocked the Roosevelt administration, and the president himself intervened to get the men back to work, while hard-liners in Congress demanded tough legislation against the right to strike in wartime.

In India the political challenge from Gandhi reached a new crisis. He went on a prolonged fast to protest his imprisonment and the British rejection of self-rule. The Times followed the drama closely. Readers were warned that “India Faces Violence If Gandhi Dies,” which was almost certainly the case. Gandhi gave up his fast in early March but the struggle for independence continued to challenge the British Empire’s war effort in Asia.

Resistance was also growing in German-controlled Europe, where efforts to recruit forced labor and the expropriation of property and artwork propelled more Europeans toward active opposition. On May 2 The Times announced that the Norwegian Norsk Hydro plant, which produced “heavy water” used in nuclear development programs, had been successfully sabotaged. The raid had taken place on February 27 and 28, but the details could not be revealed. The Times did suggest that the Germans were not yet at a stage to produce a weapon of “devastating power,” a judgment that was closer to the truth then they could have hoped.

By The Associated Press.

LONDON, Jan. 31—Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, Nazi Germany’s wily submarine warfare wizard, assumed command of the German Navy today with the prompt declaration that every ounce of German sea power was to be thrown into the submarine war against the Allies.

Raising his new Commander in Chief’s flag—a black cross on a white field—over his headquarters, Admiral Doenitz was quoted by the German radio in a broadcast recorded by The Associated Press as saying:

“I will put the entire concentrated strength of the navy into the submarine war, which will be waged with still greater vigor and determination than hitherto.

“The entire German Navy will henceforth be put into the service of inexorable U-boat warfare.

The German Navy will fight to a finish.”

The declaration was regarded here as a substantiation of views expressed previously that Admiral Doenitz’s appointment yesterday as successor to Grand Admiral Erich Raeder was a forecast of a greatly intensified U-boat campaign that already is causing marked concern in Allied war councils.

Stockholm dispatches said the elevation of Admiral Doenitz, originator of the “wolf pack” method of U-boat fighting, was regarded by observers there as a sign that Reichsfuehrer Hitler was pinning all his hopes of winning the war on the submarine weapon. Admiral Raeder, it was reported, would become a sort of honorary “first adviser on naval affairs” to Herr Hitler.

Even as Admiral Doenitz was assuming command, the German radio today announced, without verification from Allied sources, the sinking of 450,000 tons of Allied shipping in January. Included in this claim were nine Allied merchant ships of 45,000 tons which the German High Command said today had just been sunk in the North Atlantic, Arctic and Mediterranean.

Allied sources have estimated that the Germans have anywhere from 300 to 700 submarines available for duty, a third of which might be on the hunt at any one time.

FEBRUARY 2, 1943

Girls of teen age picked up in this area by service men outnumber professional prostitutes by a ratio of 4 to 1 as spreaders of venereal diseases among our armed forces, a conference on wartime control of venereal disease was informed yesterday by representatives of the Army, Navy and the United States Public Health Service.

The meeting, held at the Hotel Astor, was one of three simultaneous sessions of the eleventh regional conference on social hygiene under the auspices of the New York Tuberculosis and Health Association’s Social Hygiene Committee and 116 other sponsoring organizations. The conference was attended by nearly 1,000 representatives of the Army, Navy, Public Health Service, New York State and City Departments of Health and by doctors, nurses, magistrates, and educational and social workers from the metropolitan area.

The annual meeting and conference on tuberculosis of the New York Tuberculosis and Health Association was also held yesterday at the Astor, jointly with the Tuberculosis Sanatorium Conference of metropolitan New York. All the various groups attending the sessions met jointly at a luncheon session.

“In the present war,” said Dr. Robert E. Heering, past assistant surgeon, Public Health Service. “We find that local talent—so-called charity girls or ‘chip-pies’—is figuring more and more prominently in the spread of venereal diseases. This prominence is due in part, at least, to the fact that many communities, having finally come to the realization of their responsibilities, have made it uncomfortable for commercial prostitution, with the result that relatively fewer infections are acquired from this source.

“Professor John H. Stokes of the University of Pennsylvania has recently reported a loosening up of sex standards, citing as evidence a shift of the infection source from professional prostitute to casual.”

Quoting Professor Stokes, Dr. Heering continued:

“We find the girl-friend or pick-up performing her uncertain offices without cost, which confounds the police attack on prostitution; and we find among women and girls of the most unexpected types an almost avid desire to show the boys a good time.

“We are concentrating troops overwhelmingly in the South, in areas where both white and colored races have a phenomenally high incidence of venereal disease. The color-line is thinning, drawing on the Negro reservoir of infection, the highest in the country. The population as well as the armed forces is on the move, and civilians, equally with the soldier and sailor, are swept into the morale-wrecking effects of the change. And now, scientific discovery, the one-day cure of the maligned but often effective fear-producing deterrents of disease, is knocking the props out from under our platform.”

By FRANK L. KLUCKHOHN

Wireless to The New York Times.

ON THE TUNISIAN FRONT, Feb. 2 (Delayed)—The American Air Force fought the Germans today over the expanding battlefield in Southern Tunisia as Field Marshal General Erwin Rommel succeeded in getting some of his prize armored units into the fighting in this sector.

Both at Sened Station, on the way to Maknassy, and opposite Faid Pass, American armored units and what infantry support they could muster ran into units that Marshal Rommel—“the professor” to the American troops—has been able to rush north in an attempt to break the British First Army’s communications southward and clear the way coincidentally for his own advance to the north.

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (third from left) on the Tunisian front, 1943.

The infantry—green two days ago—succeeded today in taking the high hills east of Sened Station, giving it a commanding position there. Our tanks beyond Sened backed an estimated twenty German tanks against the mountains and captured them in heavy fighting.

But today was devoted primarily to air battles as dive-bombers raked the American positions, Messerschmitts cannonaded them and Focke-Wulfs did both. In 150 sorties, the numerically inferior planes of Major Gen. James H. Doolittle’s command sought to break up the air attack that the enemy had held in leash for such a moment.

Besides rushing troops and tanks to halt the American operating in the south under Lieut. Gen. Kenneth A. N. Anderson’s orders, Marshal Rommel is reportedly reinforcing the Mareth Line, which runs fifty miles between the sea and the mountains, with medium and heavy artillery—88-mm. guns and long-range 105s. Col. Gen. Dietloff von Arnim’s forces around Tunis and Bizerte also were making demonstrations southward against our communications lines as their air force cut loose after a week of inactivity on the ground. As was the case earlier on the northern front, where the British form the bulk of the force, as soon as our light fighter sweeps disappeared, the enemy swooped in, his bombs making it tough for our infantry. It was a measure of what the green American troops could take before giving it back that our infantry units could capture the hills beyond Sened today. I saw these troops dive-bombed time after time on their way to battle. Yesterday they were attacked by tanks but they counter-attacked. Today they moved forward despite their casualties.

For two days, American armored forces attached to General Anderson’s First Army have been battling to check the German breakthrough near Faid Pass. From an Arab rug tent camouflaged around the sides with brush I watched preparations for a counter-attack in which, as this is written, twenty-two enemy tanks have been reported destroyed against five of ours knocked out by German 88-mm. artillery.

By C. L. SULZBERGER

Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, Feb. 4—General Draja Mikhailovitch, Serbian-born de Gaulle of the Balkans, has reported by wireless to the Yugoslav Government in London that he is prepared to mobilize an army of more than 200,000 men in occupied Yugoslavia and that he is now in constant touch with Greek and Bulgarian sympathizers who are prepared to act with him when the United Nations second front opens up in the Balkans, it is stated by General Mikhailovitch’s admirers in the Yugoslav Cabinet here.

This correspondent makes no pretense to verifying these claims. That is impossible. However, this is a tale of “Draja” as told by his adherents and, like previous accounts of the Partisan movement, it should be accepted as a one-sided version in a two-sided dispute.

General Mikhailovitch can be regarded as preeminently a Serb, who wants to liberate his country and restore the prewar Kingdom of Yugoslavia under the Serbian Karageorgevitch dynasty. At the time the present war started in 1939 he was charged with planning new fortifications along the Italian-German frontiers, and he recommended that it was a foolish and wasteful expenditure because in case of attack the Yugoslav Army must be withdrawn nearer to the center of the country and there try to hold, first, in the region of the Sava River.

General Mikhailovitch, then colonel, was disapproved by the General Staff of the time and withdrawn to Belgrade, where he received a relatively unimportant job. In this sense of disagreement with his superiors on the basis of military opinion, General Mikhailovitch’s career was much like that of General Charles de Gaulle. Both have been proven right by events.

While he was in Belgrade General Mikhailovitch participated in occasional secret talks held at Zemun, across the Sava from Belgrade, in which patriot officers discussed possible action in case the government knuckled under to Axis pressure. Others who took part in these talks were General Borivoye Mirkovitch, who was a major directing force in the Yugoslav coup d’etat; General Simovich, former Prime Minister, who was selected by General Mirkovitch to be titular head of the coup, and various air force and army officers, some of whom are now abroad helping the Yugoslav cause.

When the bewildered government gave its shattered army the order to surrender to the Axis, General Mikhailovitch was one of many officers who disappeared into the mountains, as had patriotic South Slavs for centuries before when they fought occupying troops in Hajduk and Chetnik bands. Already the first shots of guerrilla resistance had been fired in Hercegovina by an independent peasant band by the time General Mikhailovitch began to organize his forces.

In the remote mountains he found Major Paloshevitch, who had refused to demobilize his battalion, and together they planned the future fight. Word of their plans began to filter through the land. Although all Yugoslav generals, good as well as bad, had lost their popular reputations as a result of the army’s collapse, General Mikhailovitch was the only colonel who did not suffer from this blot. He worked slowly, gathering recruits and cached arms and limiting himself to small skirmishes and sabotage until Germany invaded Russia, when the feeling spread through Slavophil Yugoslavia that the moment had come to arise.

According to the Yugoslav War Minister, who was promoted to general by the emigre government after his first successful attacks, his army is being thoroughly trained on a basis of regular officer cadres and a large number of noncommissioned officers, but with small irregular groups of Chetniks under them conducting limited raids. In other words, he claims to be retaining command of the nucleus of a large force while keeping many of his sworn followers in their native villages and towns prepared to rise on a given signal from his secret agents.

In this connection it is reported here that the Axis is busily trying to round up his clandestine supporters and break this organization and their agents traveling about occupied Yugoslavia, pretending to collect funds in General Mikhailovitch’s name and arresting all contributors. Between Dec. 9 and 13, 3,000 are believed to have been arrested of which number 300 were shot on Christmas Eve, and later 3,900 more were rounded up and executed.

FEBRUARY 7, 1943

The nature of this total and global war brings it about that while the United Nations are able to hail gratifying victories on some fronts, there are stalemates and touch-and-go battles on others, and there are also cries of distress and urgent appeals for help from some of our allies exposed to an immediate menace.

Such outcries and appeals, combined with foreign and domestic criticism of our conduct of the war, arose during those dark days some months ago when the Russians were apparently holding on to Stalingrad and the passes of Caucasus with little more than the skin of their teeth and grim determination, and when our Marines were fighting for their little beachhead in the Solomons. There were cries for the second front, for more lend-lease aid to Russia, for more troops and supplies for our hard-pressed forces on Guadalcanal. As soon and as adequately as it was humanly possible, supplies were sent to Russia at great risk and cost, a second front was established in Africa, and the German disaster in Russia began to take shape. Likewise, our troops in the Solomons received reinforcements and drove back the Japanese.

Now there come similar outcries and appeals from both Australia and China. The first is menaced by a Japanese invasion, the second is pictured as being close to an economic collapse. Nobody will deny the justification of these pleas, or minimize the dangers which they picture. If either of these dangers should materialize it would be a catastrophe of great magnitude for all the United Nations.

Yet, in answer to frequent criticism that our aid to China or Australia is still inadequate, it must be pointed out that what we can send is determined in large part by circumstances at present beyond our control, and that the battles fought in Russia, in Africa or in the Solomons are as much battles for China and Australia as for any other country. Unfortunately, despite the American and British production miracles, there is just so much to go around. There are just so many planes, and tanks, and guns, and there are just so many ships to transport them to the front lines. In the Pacific all our available forces are in there fighting to protect Australia. And in North Africa all available United Nations forces are likewise fighting, not only to drive out the Germans and Italians and thereby blast a way for an invasion of the European continent, but also to open up the Mediterranean as a supply route to India, Burma and China, without which a major campaign from these regions is impossible.

In this global warfare it is a question of nice military judgment as to just where the available manpower and resources should be utilized to obtain maximum results. Nobody will today challenge the wisdom of the aid to Russia or the African landing which averted a German-Japanese junction in the Middle East. And if there was not enough left to provide more aid to the Far East than was actually sent, that was not a fault of distribution but a result of the original sin of all democracies—the sin of being unprepared for war.

By ROBERT TRUMBULL

By Telephone to The New York Times.

ABOARD THE U.S. SUBMARINE WAHOO, at a Pacific Base, Feb. 9—An engagement with a Japanese destroyer in a finger-like bay of Mushu Island, north of New Guinea, followed by a running torpedo and gun battle with a four-ship convoy the next day, gave this new submarine of the Pacific Fleet the right to wear a broom tied to her periscope when she came into port. The broom, by naval usage, denotes a “clean sweep.” The Wahoo earned the unofficial decoration by sinking all four ships of the convoy, in addition to the destroyer.

The Wahoo’s captain, Lieut. Comdr. Dudley W. Morton, 35 years old, of Miami, Fla., and his executive officer, Lieut. Richard H. O’Kane, 32 years old, of San Rafael, Calif., told the story of this and later engagements that took place after the Wahoo had fired all her torpedoes. Regarding one of these, Lieut. Comdr. Morton remarked: “It was another running gun battle—destroyer gunning, Wahoo running.”

The Wahoo’s adventures on this patrol in the New Guinea area were compressed into five days crowded with peril. Once two members of the crew were wounded “as a result of enemy action.”

A pharmacist’s mate had to amputate two toes of one of the men while the submarine was still under fire. Lacking surgical tools, he used a pair of wire-cutting pliers for the operation. The patient, Fireman H. P. Glinsky, is now doing well.

This pharmacists’s mate, L. J. Lindhe of Wisconsin, affectionately dubbed “the Quack,” has been giving the back of Lieut. Comdr. Morton’s neck a daily massage for the past five days to relieve tenseness of muscles resulting from the action.

“A form of being scared, gentlemen,” Lieut. Comdr. Morton told the press, explaining how he got the sore neck.

At the time of the action Lieut. Comdr. Morton was exploring the new Japanese harbor of Wewak on the northern coast of New Guinea. We-wak is one of the advance bases being established by the Japanese as General Douglas MacArthur’s conquering forces drive them from their former strongholds in the regions of Buna and Gona. Wewak Harbor was then uncharted, but one of the enlisted men on the Wahoo had a 25-cent atlas that shows the location. Lieut. Comdr. Morton’s officers traced the area from the atlas and enlarged this by photography to obtain a satisfactory map.

Mushu Island lies a short distance off Wewak. While nosing around there submerged, Lieut. Comdr. Morton spotted a ship in Mushu’s narrow bay. It was a Japanese destroyer at anchor, possibly an escort for the convoy the submarine wiped out the next day farther north.

As the Wahoo fired a torpedo and missed, the destroyer upped anchor and drove in to attack. The Wahoo fired several more torpedoes, but all missed because the range was too long to hit a fast target. The last immediately available torpedo was fired at a range of 800 yards The destroyer steamed on, firing her guns and met the tin fish almost half-way, or at 500 yards.

The torpedo hit amidships, scrambling the destroyer’s vital installations, and she burst in two. Into the sea went a large number of white-clad Japanese sailors who had been acting as lookouts in the riggings, on the yardarms, on top of the turrets, every place a man could hang on. The warship went down in two sections, bow first, in five minutes.

Two days later, on Jan. 26, the Wahoo sighted the convoy of two freighters of 7,000 to 9,000 tons, a 7,000-ton transport and a tanker of about 6,000 tons. The transport was loaded with troops, of whom Lieut. Comdr. Morton believes there were no survivors.

The Wahoo torpedoed and sank a freighter first, then the transport. It wounded the other freighter, then knocked off the tanker before pursuing the crippled ship. There ensued a running battle.

“We were inclined to laugh at the freighter’s erratic firing,” Lieut. Comdr. Morton said, “but a shot that landed right in front of us wiped the smirks off our faces.”

We finally sank the freighter at about 9 P.M.

BOMBAY, Feb. 10 (AP)—With India apprehensively alert, Mohandas K. Gandhi started a twenty-one-day hunger strike today, to subsist on citrus fruit juice mixed with water, but not to “fast unto death” as he threatened on previous abstentions. His fast is in protest against his confinement behind barbed wire in the palace of the Aga Khan at Poona.

The 73-year-old independence leader imposed the limited diet upon himself after long correspondence with the Marquess of Linlithgow in which the Viceroy advised against it for reasons of health. The Viceroy asserted it constituted “political blackmail for which there can be no moral justification.”

Mr. Gandhi went ahead, however, with the objectives of compelling the government to alter its policy of locking up members of the All-India Congress party “for the duration” and to protest against the “leonine violence” which he accused the government of using to suppress the civil disobedience campaign.

The correspondence of Mr. Gandhi and the Viceroy was published by the Government of India today with an accompanying statement that the government had informed Mr. Gandhi he would be released for the purpose and for the duration of the fast and, with him, any members of his party who wished to accompany him.

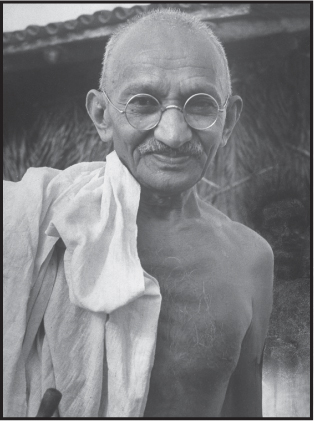

Mohandas K. Gandhi in 1943.

“Mr. Gandhi,” the statement added, “has expressed his readiness to abandon his intended fast if released, failing which he will fast in detention.”

The government statement said “it is now clear that only his unconditional release could prevent him from fasting.”

“This the Government of India is not prepared to concede,” it added.

Mr. Gandhi in his letters to the Viceroy denied that the Congress party was responsible for slayings, train-wreckings and other violence of the past few months. He demanded his unconditional release from the palatial surroundings where he has been confined since last Aug. 9 after a new civil disobedience campaign broke out against British rule.

This is Mr. Gandhi’s ninth fast in twenty-five years. The first in October, 1918, lasted three days in support of a cotton mill workers’ strike at Ahmedabad. The second, in February, 1922, lasted five days, in condemnation of his Indian followers for burning a policeman alive. The third, of twenty-one days, was in September, 1924, on behalf of Hindu-Moslem unity.

In Yerawada jail he undertook a “fast unto death” which lasted thirteen days in September, 1932. It ended when the British Cabinet withdrew its decision to have separate elections for Untouchables, which Mr. Gandhi contended would split Indian ranks.

His fifth fast lasted twenty-one days in May, 1933, and was undertaken as a form of purification for his followers. The sixth, in August, 1934, was directed against over-zealous reformers. His seventh, in the same month, lasted a week. He undertook it to compel the British to permit him to edit his weekly publication Harijan from jail. He went without food again for four days in April, 1939, over a local political problem.

The hunger strike has also been used against Mr. Gandhi. In October, 1934, he declared himself “a dead weight” on the Congress party and offered his resignation. Seven of his followers fasted until he changed his mind.

FEBRUARY 17, 1943

An official summary of extensive air and naval operations in the Solomons area from Jan. 29 through Feb. 7 reveals at least part of what happened during the Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal. No ships met in battle except some torpedo boats and destroyers. Those lost on both sides went down under air attack. We did not prevent the evacuation, and suffered substantial naval loss. The American heavy cruiser Chicago was sunk by torpedo planes on the second day of continuing engagements in which we also lost an unnamed destroyer and three PT boats. Against this we claim two enemy destroyers certainly sunk, four probably sunk and eight others, with three smaller craft, damaged.

Our loss was not “extremely light,” as first reported. The Chicago was a fine 9,300-ton vessel, mounting nine 8-inch guns. She is undoubtedly the “battleship” which the Japanese announced they had sunk off Rennell Island, together with another “battleship” and three cruisers. The Chicago was damaged by aerial torpedoes and succumbed to torpedo plane attack the next day while under tow. Fortunately, most of her crew were saved. Exaggerated Japanese claims may be based on other damage inflicted on our ships, but not yet reported by us.

Apparently the descent of the Japanese rescue fleet with battleships and carriers on Guadalcanal almost coincided with the approach of an American task force convoying transports to our island base. The troops were safely landed; but at dusk, south of Guadalcanal, our fighting ships were sharply attacked by enemy carrier planes and dispersed. Meanwhile, twenty enemy destroyers were taking the remnants of their beaten force from Cape Esperance. One at least was sunk in this attempt. When our main naval forces swept northward the Japanese capital units, which had come down from Truk, withdrew to safer waters, pursued by our ships and planes. In this flight the Japanese suffered their chief loss, not too heavy from their standpoint, considering the risk involved. Apparently our battle fleet was ready and eager to engage the enemy, but that opportunity still lies ahead.

A German U-Boat in 1943.

FEBRUARY 21, 1943

By Rear Admiral Emory S. Land,

Chairman, U.S. Maritime Commission, and Administrator, War Shipping Administration

The greatest threat confronting the Axis is the steady translation of American resources and industrial might into fighting power. Germany, Italy and Japan know that the strength of this nation, added to the already fully mobilized forces of our Allies, will eventually crush them unless by some means they can prevent complete utilization of that power in the grand strategy of the United Nations.

This is the reason for Germany’s intensive submarine campaign in the Atlantic. If the Nazis are to avert the full impact of American productive power on the battlefront, they must neutralize that power before it can be hurled against them. Since they have not destroyed our cities, shipyards and factories, they must concentrate on attempting to send our ships to the bottom.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” is but one phase of our efforts to meet the challenge. It has been a spectacular phase, and one in which the naval forces, the air forces and the merchant marine of the United States and Great Britain have distinguished themselves. But other phases of the war of production and transportation have been carried on with equal intensity and are having their effect in gradually wearing down the power of Germany’s undersea “wolf packs.”

The submarine threat to the maintenance of our transatlantic lifelines is being met in three ways: (1) by striking at enemy submarine construction, repair and servicing bases, (2) by accepting the challenge at sea through convoy and patrol operations and (3) by building new merchant ships to replace our losses and to increase our available tonnage. Information about the first two items is restricted, for reasons of military censorship and security. Concerning the third item, one may express some very definite views.

The question most frequently asked of those administering the merchant shipbuilding program is: “Are we building ships at a rate faster than the rate of sinkings?” The implication is that the United States has set out to solve the sinking problem by sending out more ships than the Nazis can sink. The question seems to imply the placing of an unfair burden of responsibility upon the shipbuilder when, in fact, the answer to the problem is only partly in his hands.

The fortunes of war are subject to much more rapid change on the battlefront than on the production front. The rate of sinkings can rise or fall more quickly than the rate of shipbuilding. Moreover, as I have frequently emphasized, you can sink a ship far faster than you can build one—even in these times when we are turning out Liberty Ships in an average time of fifty-five days.

Whether submarine activity will grow worse in the future is something one cannot predict. It is a fact, however, that this type of naval thrust at our shipping is more active in the Winter months, when nights are longer and conditions at sea are less favorable to surface craft and more favorable to submarine operations. With the coming of Spring and Summer it is possible that we may see some slackening off in the activity of German U-boats. But that will be governed by the exigencies of war. The Nazis, we may be sure, will send their submarines wherever they are most useful as the United Nations press onward with the offensive begun in the closing weeks of 1942. Submarines go where “the fishing is best.”

The amazing progress of shipbuilding in the United States during the last year is an indication of the ingenuity and enterprise of the American people and our determination to win this war. Fortunately, a fair start had been made on the Maritime Commission’s long-range building program when the call for sudden expansion of facilities and stepping up of the program came with the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939. At that time the commission was working on its schedule of building fifty ships a year for ten years, and some of these vessels had already been turned out.

The start was slow, but the progress has been rapid and gratifying—if not startling. To speed production and utilize the type of engines that could be produced in large numbers, the commission settled on a standardized design in the Liberty Ship of 10,500 deadweight tons. It took an average of 235 days to build the first two of these vessels, which were delivered in December, 1941. In December, 1942, when eighty-two Liberties were delivered, the average building time was reduced to fifty-five days. Performance like this, combined with an increase of more than 600 per cent in shipbuilding facilities, made it possible to turn out 746 ships, totaling 8,090,800 deadweight tons, in 1942.

The commission’s directive from President Roosevelt was to build 8,000,000 tons of ships last year. Our directive for 1943 is for at least 16,000,000 tons, which will give us a total of about 2,300 vessels, totaling 24,000,000 tons, in the two years. I am confident that we will fulfill the President’s directive this year.

By JANE HOLT

The point rationing of processed foods, according to the Office of Price Administration, is the most far-reaching rationing yet imposed by war necessity. It affects almost every man, woman and child in the nation

Only A, B and C stamps may be used during the first month. Point values will fluctuate as food supplies vary nation. Here, briefly, are some questions that may occur to you in connection with the program, together with answers that are intended to help you adjust yourself to the regimen:

Q: How does point rationing differ from other methods of rationing?

A: This is best answered by a brief definition of the three systems now in use. The simplest is coupon rationing, which is used in rationing single commodities—sugar and coffee, fuel oil and gasoline. By this time you are thoroughly familiar with its workings.

The second system, rationing by purchase certificate, is the one now in use for the rationing of automobiles, bicycles, heating stoves, heavy-duty rubber footwear, tires, tubes and typewriters. Here is how it functions: A person desiring one of the items listed applies to his local Rationing Board, which issues a form for him to fill out. The applicant supplies the information, and if this complies with the requirements the board issues a Purchase Certificate, which the consumer must present when he purchases the item.

The third point rationing is a method for rationing many articles in one group of related commodities, which may be used interchangeably. The remainder of this column is devoted to an explanation of how point rationing operates.

Q: Why do we need point rationing?

A: Point rationing is a system for rationing all items in a group of closely related commodities. If only some of the goods in such a group were rationed—the scarcest ones, for example—consumers would rush to buy the others and they would soon disappear from the stores. On the other hand, if all the goods were rationed separately—as coffee and sugar and gasoline have each been rationed—different stamps for every individual product would have to be issued. This might mean hundreds of various ration stamps, which, in turn, would mean endless confusion for all concerned.

Q: What is a point?

A: A point is a ration value, much as dollars and cents are money values. Each rationed food will be worth so much in currency and so much in points. The size of the supply will determine the number of points given to an article; the price and quality will have no bearing. Thus, for example, if peas are more plentiful than beans, peas will have a lower point value than beans. You can see that this system enables the government to steer consumers away from buying scarce items and encourages them to purchase those that are comparatively abundant.

Naturally, a large can of corn—or anything else for that matter—will be worth more in points than a small one. In establishing the point values of varying amounts of the same food the net weight of the contents of the can will be the deciding factor.

Q: What sort of foods will be point rationed?

A: Processed foods: canned and glassed fruits, vegetables, soups and juices; dried fruits; frozen fruits and vegetables; chili sauce and catsup. Processed baby foods—strained or chopped preparations made of fruits, vegetables or meats—also will be included.

Q: When will the point rationing of processed foods go into effect?

A: On March 1. This week retail sales of these foods will be suspended to permit wholesalers and storekeepers to prepare for the program and to allow civilians to apply for War Ration Book No. 2.

Q: What is War Ration Book No. 2?

A: This is the book containing the stamps that will be necessary in procuring processed foods. Later it will be used in meat rationing.

Q: Would you indicate how War Ration Book No. 2 is to be used by describing its contents?

A: You will find that Book 2 contains blue and red stamps. The blue stamps are to be used in purchasing processed foods; the red stamps are to be reserved for meat rationing, which is expected to start April 1. In addition, each stamp is lettered and numbered. The letters tell you when the stamps may be used—only A B and C stamps may be used during March, the first ration period—and the figures tell you the point value of each stamp.

Q: How will I know the point value of a rationed food?

A: Toward the end of this week the government will issue an official table of point values, which your grocer must post where you can see it. This will tell you exactly how many points each rationed food is worth. Modifications, probably not oftener than once monthly, may be made in the table, which will be the same throughout the country.

Q: Does it make a difference how I spend my stamps?

A: Yes, to a certain extent it does. Using the high-point stamps first means that you won’t be left at the end of a month with anything but an eight-point stamp to exchange for a six-point purchase. You should avoid such a situation, because your grocer isn’t permitted to make “change” in stamps. If what you buy is lower in point value than the stamp you present, you’ll lose some of your points.

A gas rationing booklet from the 1940s.

Q: How can I best budget my points?

A: One way to do it is to figure out your family’s approximate weekly point allowance. Each person is allowed forty-eight points a rationing period, which means that, if your family consists of two, you have approximately twenty-four points a week to spend. Then list the point-rationed foods and the quantities you expect to buy for the week, jotting down the point value beside each item. Add up the points and compare the sum with your family’s point allowance for the week.

If your total is less than the weekly budget, then, obviously, no changes are necessary. If it is more, you will have to modify your list. This can be done by substituting low-point foods for those that have a high-point value, and by shifting to fresh fruits and vegetables in some instances.

Q: What happens when my son, who is in the Army, and has no ration book, comes home on furlough?

A: If your son is on furlough for seven days or longer he presents his leave papers to the local rationing board, which will issue a point certificate, allowing enough points to cover his leave period. Your grocer will accept this point certificate instead of point stamps.

Food ration stamps must be torn out of the book in the presence of your grocer or in the presence of the delivery boy.

By DREW MIDDLETON

Wireless to The New York Times.

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, Feb. 21—German tanks and two battalions of infantry cracked the stubborn Allied defense yesterday and occupied the highly important Kasserine Pass, twelve miles from the nearest point on the Algerian frontier, as the second phase of the German offensive in Central Tunisia got under way.

Veteran British armored units that had rushed south during the past week joined an American combat command in heavy fighting that continued through yesterday and early today. American and British tanks lunged forward together, leading their infantry comrades in counter-attacks against the steel fingers of Field Marshal General Erwin Rommel’s army reaching for Tebessa, Algeria, the junction of four main roads and two railroads.

Defying heavy clouds that hung over the battlefront, Airacobras of the Twelfth United States Army Air Force harried enemy supply columns winding toward the front. A number of trucks were damaged by cannon and machine-gun fire in attacks that followed a night raid by Royal Air Force Bisleys against targets on these roads and others farther south in the Gafsa area. German communications were also attacked by these medium British bombers Friday night, but bad weather prevented accurate observation of the results.

Besides the successful attacks on the Kasserine Gap, the enemy made one other offensive movement. For the second time in two days a strong armored reconnaissance force probed the British positions near Sbiba. Again they were met by the ubiquitous guards; who knocked out two tanks and severely damaged two more. [The French also claimed a role in this action.]

Enemy losses in the fighting at Kasserine are believed to equal the heavy ones suffered in the first attack Thursday. The second push, however, was preceded by much heavier fire from heavy and medium artillery, which reportedly silenced American guns in the gap and on the hills to each side.

Dive-bombers, which played a major part in the break-through at Faid just one week ago, did not have an important role in this attack. The gap was won mainly by guns, tanks and infantry after hours of severe fighting in which the Americans and British counterattacked with reckless abandon.

The entire Allied position in Western Central Tunisia is affected by the smash through the gap northwest of Kasserine, which showed again that the enemy was willing to commit large forces for taking geographical positions essential in that country. Should Marshal Rommel swing west on Tebessa, the communications of all American and British forces in that area would be seriously threatened. If he turns northward against the rear areas of the British First Army, a further adjustment of the Allied line will be necessary to meet this attack on the open flank.

Another Setback for the Allies in Mid-Tunisia: Marshal Rommel’s infantry and tanks captured the pass northwest of Kasserine (1). He may now turn to the right and make for Thala or turn to the left, force his way through the pass at Djebel Hanira, break into the comparatively flat country beyond Tebessa and strike for Constantine (shown on the inset). East of Sbiba (2) a new German thrust was smashed back. The British Eighth Army drove eight miles beyond Medenine (3) on the road to Mareth and the railhead at Gabes.

But all the indications are that Marshal Rommel intends to pursue his attacks against the American and British troops in the Tebessa region. It must be noted that the movements of the last few days have left the German forces open to a counter-attack from the north. Whether General Sir Harold R.L.G. Alexander, commanding the Allied land forces, can risk committing the First Army’s reserves to such an action while Col. Gen. Dietloff von Arnim waits at the head of the Medjerda Valley in Northern Tunisia is a difficult problem for the Allied commander.

The bulk of the best German troops is being used in the present offensive, the future of which will be dictated by the German losses in tanks. If the enemy can recover enough Allied tanks to replace his own losses and give him reasonable security for the coming battle with General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery’s British Eighth Army, the battle of Kasserine Pass is only the first step in a serious and very threatening offensive.

MARCH 2, 1943

Immediate action by the United Nations to save as many as possible of the five million Jews threatened with extermination by Adolf Hitler and to halt the liquidation of European Jews by the Nazis was demanded at a mass demonstration of Christians and Jews in Madison Square Garden last night.

The demand by religious, civic, political and labor leaders was heard by an audience of 21,000 that filled the huge auditorium, while several thousand others were unable to get in.

By 8 o’clock, shortly before the meeting opened, the approaches to the Garden were closed by the police, but 10,000 persons remained standing in Forty-ninth Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, and heard the addresses through amplifiers after many thousands of others who were unable to get in had dispersed. Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, president of the American Jewish Congress, who presided, announced from the platform, on the basis of police estimates, that 75,000 persons had tried to make their way into the Garden in the three hours before the meeting opened.

Joining in support of the demonstration from overseas in messages read at the meeting were the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Hinsley, Archbishop of Westminster, who is gravely ill in London, and Chief Rabbi J. H. Hertz of Great Britain. Sir William Beveridge, author of the Beveridge plan for social security, addressed the meeting by radio from the British capital.

The “Stop Hitler Now” demonstration was under the joint auspices of the American Jewish Congress, the Church Peace Union, the Free World Association, American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations and other Christian and Jewish bodies.

A resolution offered by Louis Lipsky, chairman of the governing council of the American Jewish Congress, and adopted unanimously, proposed an eleven-point program of action to achieve the purposes of the demonstration.

The resolution will be submitted to President Roosevelt and through him to the United Nations.

Mayor La Guardia spoke in the name of the people of New York. Dr. Chaim Weizmann, president of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, spoke in behalf of the entire Jewish community.

Governor Dewey addressed the meeting by radio from Albany. From Washington came radio addresses by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas and Senator Robert F. Wagner. A message was read from Wendell L. Willkie, who declared that “practical measures must be formulated and carried out immediately to save as many Jews as possible.”

The keynote of the meeting was struck by Herman Shulman, chairman of the special committee of the American Jewish Congress on the European situation, who in introducing Dr. Wise as presiding officer of the meeting called attention to the fact that “months have passed since the United Nations issued their declaration denouncing the unspeakable atrocities of the Nazis against the Jews and threatening retribution,” with the promise that “immediate practical steps would be taken to implement it,” but that nothing had been done as yet.

The climax of the meeting was reached after Cantor Morris Kapok-Kagan had sung “El Mole Rachmim,” Hebrew prayer for the dead, memorializing the Jewish victims of the Nazis. This was preceded by the blowing of the shofar, the ram’s horn, by Rabbi Maurice Taub, and as the sounds subsided and Mr. Kapok-Kagan began the prayer the huge audience wailed and wept, while the thousands outside, who heard the proceedings through amplifiers, joined. There followed the reading of the Kaddish, another prayer for the dead, by Rabbi Israel Goldstein, and the reading of a passage from the Psalms by Rabbi Jacob Hoffman, ending with the words, “Save, Lord: Let the King hear us when we call.”

The message from Chief Rabbi Hertz read:

“It is appalling to think that Whole of mid-European Jewry stands on brink of annihilation and that millions of Jewish men, women and children have already been slaughtered with fiendish cruelties which baffle belief, but equally appalling is fact that those who proclaim the Four Freedoms have so far done very little to secure even the freedom to live for 6,000,000 of their Jewish fellow men by readiness to rescue those who might still escape Nazi torture and butchery. May God grant that your great demonstration of American Jewry be the means of overcoming the strange and calamitous inertia of those who alone can initiate the sacred work of human salvage.”

Dr. Weizmann called upon the United Nations to implement their expressions of sympathy for the Jews by deeds.

“Two million Jews have already been exterminated,” he said. “The world can no longer plead that the ghastly facts are unknown and unconfirmed. At this moment expressions of sympathy, without accompanying attempts to launch acts of rescue, become a hollow mockery in the ears of the dying.

“The democracies have a clear duty before them. Let them negotiate with Germany through the neutral countries concerning the possible release of the Jews in the occupied countries. Let havens be designated in the vast territories of the United Nations which will give sanctuary to those fleeing from imminent murder. Let the gates of Palestine be opened to all who can reach the shores of the Jewish homeland. The Jewish community of Palestine will welcome with joy and thanksgiving all delivered from Nazi hands.”

By HERBERT L. MATTHEWS

Wireless to The New York Times.

POONA, India, March 3—Mohandas K. Gandhi’s twenty-one-day fast ended in defeat and failure at 9 o’clock this morning [11:30 last night in New York].

His life has been saved against all belief, but politically it has been a blow, to his reputation and to the Congress movement. He pledged a fight to the finish against the British last August; now he has lost the second round.

The government forbade any demonstration in connection with the breaking of the fast, only Devadas and Ramdas Gandhi, sons, and a few fellow-prisoners were present. This is the first time Mr. Gandhi has failed to achieve his object by fasting. This has disappointed and discouraged him. Therefore, he is hardly likely to let things rest as they are.

His first task is to regain some of the strength he has lost by his astonishing ordeal. Anxiety for his health will continue for weeks.

To what extent his faith and that of the Hindu community is shaken by this defeat cannot be ascertained yet. The Hindus still assert that they had tremendous popular backing in their pleas for Mr. Gandhi’s release and that there will be an aftermath of bitterness that will make reconciliation more difficult than ever.

The British, on the other hand, are pleased at what they consider to have been a brilliant stroke of judgment by the Viceroy, the Marquess of Linlithgow, who for the second time in less than a year has demonstrated that the Congress party is not nearly as strong as it claims to be.

There was little mass expression of sympathy, concern or even interest, except when Mr. Gandhi appeared to be dying. The bulk of the Moslems and all the princely States remained on the side-lines. Even the Hindu Mahasabha, the most important Hindu political organization other than the Congress party, deplored the fast.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, head of the Moslem League, again profits by Congress blunders. Although he has carefully refrained from rubbing it in during Mr. Gandhi’s fast, he must be delighted at the turn events have taken.

World reaction to his fast has also disappointed the Hindus. Neither they nor Mr. Gandhi seems to have taken into consideration that the rest of the world is absorbed in the war. In general the consensus here is that Mr. Gandhi has made the greatest mistake of his career and primarily because he overlooked the war factor. That made the British willing to face the risk of his death with all its consequences. One result of this failure is that it should be his last attempt to gain anything from the British by fasting.

In any event it is the war that will determine the government’s reaction to any Congress move, just as it has to Mr. Gandhi’s fast. India is going to be a base for one of the main attacks against the Japanese one of these days when the reconquest of Burma takes place. Meanwhile the British feel that India must be kept peaceful and under control.

MARCH 28, 1943

By The Associated Press

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, March 27—American troops launched a surprise offensive toward Fondouk in Central Tunisia today and met with initial success as the British Eighth Army, doggedly fighting its way into the Mareth Line fortifications, was reported to be “proceeding according to plan in spite of stiff resistance by the enemy.

[The Axis-fed Paris radio said yesterday that a strong British push against the southeast flank of the Mareth Line had forced Axis troops to “withdraw from their forward positions,” The United Press reported.

[Berlin, broadcasting a D.N.B. dispatch, said that British and American troops appeared to be preparing to launch offensives in both Northern and Central Tunisia and that detachments of crack British troops had recently reached the Medjez-el-Bab area from England, British and American movements were described as “considerably stronger” in both sectors and the Allies were reported to be bringing up heavy concentrations of artillery.]

The American push on Fondouk, which is fifteen miles southwest of an important Axis air base at Kai-rouan, was reported to be making “good headway.” The drive began after a German infantry attack had been repulsed east of Maknassy, more than 100 miles south of the scene of the new fighting.

On the Maknassy–El Guettar front, where Lieut. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s main concentrations of men and armor are probing for a passage through the rugged hills to the Mediterranean, there was only local activity yesterday as rainstorms swept across Tunisia.

Special Cable to The New York Times.

LONDON, April 3—“Heavy water,” derived by an electrochemical process from ordinary water, with hidden atomic power that can be used for the deadly purposes of war as well as the happier pursuits of peace, apparently has become a source of anxiety for those Allied leaders who plan attacks against enemy targets.

Reports reaching Norwegian circles in London cite German sources as having announced on Wednesday that as a result of the work of “saboteurs,” a big electrochemical plant at Rjukan, Norway, had been blown up in what is said to have been one of three recent raids against that enemy-occupied country.

The importance of Rjukan as a target for destruction is that it is a huge plant on a wild river, from the waters of which a queer chemical known as “heavy water” the discovery of which won a Nobel Prize in 1934 for Professor Harold Urey of Columbia University, is produced, and it can be used in the manufacture of terrifically high explosives.

Heavy water or, more correctly, heavy hydrogen water, is believed to provide a means of disintegrating the atom that would thereby release a devastating power. While it is not believed here that the Germans, even with all their expert chemical knowledge, have developed some fantastic method of hurling the shattering force of split atoms at Britain, it is known that heavy water, when added to other chemicals, gives a powerfully destructive force, just as it can help in the production of new types of gasoline, new sugars, new textiles and numerous other utilitarian as well as medical developments.

Consequently, Norwegians living in London studied with interest the report emanating from Stockholm Wednesday that Rjukan had been so heavily attacked by “saboteurs” that the Germans had declared a state of emergency. They considered that if the plant had been destroyed the Germans had suffered a severe loss in their output of ammunition.

At Rjukan one quart of heavy water can be produced from 6,000 gallons of ordinary water by an electrochemical process, the formula for which was given to the world by American scientists.

Rjukan is just south of a 3,500-square-mile area in a barren mountain plateau region known as Hardangervidda, which the Germans shut off to all civilians April 1. Recent German reports have said that R.A.F. transport planes towing gliders have dropped parachutists around that area.

APRIL 4, 1943

By C. L. SULZBERGER

Wireless to The New York Times.

ALGIERS, April 3—The average American infantryman is somewhat cockily overconfident when he approaches his first battle experience, pretty damned scared when he actually gets in the thick of things and slightly bewildered for a time, then sore as hell and anxious to do something effective to an enemy who is causing him all sorts of discomforts such as having to spend a good deal of time dodging in and out of slit trenches.

After the first wind is taken out of his sails by initiation into the arts of dive-bombing and drumfire and he finds he is still alive, he is likely to become a veteran moderately quickly and by and large to develop considerable offensive-mindedness. He also begins to appreciate the skill of his veteran German enemy and the pluckiness of the British Tommy who fights beside him, and the reason for all the discipline of the toughening processes he has been subjected to in months of tedious training.

In other words, the green Yankee soldier going into action for the first time is certainly not as good as he thinks he is but he has enough horse sense to realize quickly his own deficiencies and to try to do something about it. He is just as likely as not to learn the hard way by burning his fingers, but he does learn.

These in a broad sense are the opinions of qualified observers who have had a chance to observe the development from draftees of doughboys at the front and make comparisons with some of the more experienced soldiers of other armies.

The American is a good scrapper but he has to learn the technique of modern warfare and he is generally doing that by tasting battle first. When the newcomer arrives in the line he is much in the position of the tough street fighter facing a skilled heavyweight and he has got to learn the tricks fast.

The first time a unit enters battle it is likely to get the shakes, and such cases of shellshock as are likely to develop will start then. Frequently green units do not do terribly well in the initiation, partly because those that have come here so far are insufficiently trained in such hard courses as British battle schools for getting used to actual fire.

Sometimes the mere noise gets them down at the start. But once they have been in action, especially the hard ones such as Kasserine, and have discovered that lots of shooting does not mean they will be killed, they begin to gain confidence, and if they lose a pal they get very sore indeed.

Frequently it takes more than one or two actions to get the doughboys working in cohesion, and even after five or six battles they do not function as smoothly as the Germans: they have not learned to do things automatically and without considered thought.

The way a unit learns can be exemplified by the experience of one unit that was brought up absolutely green for the second battle at Sened Station. They were dive-bombed four or five times the first afternoon and deserted their trucks, but returned when their officers called them back. About the fourth occasion one of the soldiers was heard to say, “They cannot stop American infantry that way.”

The next day in their first real action they broke under combined infantry and tank attack. However, they managed to re-form and counter-attack. They eventually took their objectives.

Another example of quick learning was demonstrated in the case of another outfit which, although it broke at Kasserine Pass, only a few weeks later at the last battle of El Guettar, stayed in its fox holes calmly, let the German tanks pass through to he taken care of by the artillery, then smashed the enemy infantry like old hands.

Our troops are learning that mobile warfare is entirely different from trench fighting and it is hard for them to master the cohesion between arms and units. For this instruction under battle conditions is absolutely essential. It has also been discovered in this great and bloody African war school that we definitely lack sufficient training in small units, although this has been stressed in all the Army’s recent peace-time manoeuvres.

A sample of how this is mastered the hard way by American soldiers may be instanced. One combat team of the First Armored Division realized through bitter experience that you cannot advance against established enemy positions directly because the artillery will knock you to pieces. Although that lesson was stressed to two other combat teams, they each made the same mistake and had time to learn the hard way—but they did learn.

Instinctively that average soldier is beginning to realize how to appreciate automatically when to stand, when to fall back, and when to wait for the artillery to take care of things.

While the biggest thing acquired in this literal school of battle is realization by the doughboy that he must learn how to win, he also had psychological experience in the realization of the true value of previously accepted luxuries. He is beginning to wonder if people back home actually appreciate what he is up against and are taking the war seriously enough.

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, April 6—With an increased number of U-boats now operating against Allied shipping and apparently employing new tactics, the Battle of the Atlantic swung in favor of the Germans last month and the submarine sinking toll was “considerably worse” than in February, Secretary of the Navy Knox declared today at his press conference.

Declaring that the situation was both “tough” and “serious,” Mr. Knox asserted that “nobody is a bit complacent about it or should be.”

He hinted that the U-boats, reported to be operating in “wolf packs,” with various packs apparently cooperating with one another, had adopted different tactics lately. He did not elaborate on this point.

The present danger zone is sweeping in its scope, the Secretary declared. The U-boat packs are operating in mid-Atlantic, he said, with emphasis on the North Atlantic route to England. Activity also has occurred on the Mediterranean route.

The brightest ray of hope held out by Mr. Knox, who repeatedly has warned that the submarine menace would be heightened this Spring, was “a very marked improvement” in the production pace of the Navy’s destroyer escort program. The Navy is banking heavily on the effectiveness of this new type of submarine-chaser, which is relatively quick and economical to make and is highly manoeuvrable.

The program is still being retarded by a scarcity of motors for the vessels, Mr. Knox said, but even that aspect is “getting better in every respect.” On April 17, he announced, he plans to make a speech at a General Electric plant in Syracuse which less than a year ago was “nothing but a hay field.” Now it is turning out fifty turbogenerators a month for Navy escort vessels.

Mr. Knox said it was difficult to assess the results of the Royal Air Forces’ heavy raids on submarine pens at St. Nazaire and Lorient in France and elsewhere. Navy men recognize the difficulty of penetrating with bombs the thick slabs of concrete with which these pens are protected, but Mr. Knox said it might be “assumed” that the raids were “embarrassing” the Germans, even if the damage was confined to the plants and towns around the pens.

APRIL 7, 1943

By The Associated Press.

WASHINGTON, April 6—Following is the “preliminary draft outline of proposal for a United and Associated Nations Stabilization Fund” announced by the Treasury:

I. PURPOSES OF THE FUND

II. COMPOSITION OF THE FUND

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, April 10—An indication of the extraordinary steps taken to safeguard the nation’s treasure of historic documents, valuable paintings and other important mementos was given this week in an announcement that the Declaration of Independence would be taken from a secret place of safekeeping for display Tuesday when the Jefferson Memorial will be dedicated at the celebration of the bicentennial of Thomas Jefferson’s birth.

Among other articles taken from Washington to secret depositories since Pearl Harbor are the Constitution, the Lincoln Cathedral Copy of England’s Magna Charta, entrusted to the United States for safekeeping by the British Government, the Articles of Confederation and the Gutenberg Bible.

All of these are in custody of the Library of Congress, which obtained Congressional appropriations of $130,000 to make its valuables secure. The library has shipped out 4,723 boxes of rare and irreplaceable materials.

The National Archives, recently adjudged the most nearly bombproof building in Washington, has felt it necessary to evacuate nothing except highly inflammable nitrate-based films.

The Smithsonian Institution, under twenty-four-hour guard like the other depositories, has evacuated what a spokesman called “absolutely Grade A material” which would serve as a nucleus for rebuilding its collection if everything else was destroyed. The material includes a few highly important paintings from the National Gallery of Art and “a vast number” of scientific specimens such as the first example of each species made known to science.

APRIL 12, 1943

A national campaign against all types of discrimination against Negroes in the armed forces and in industry was approved yesterday at the closing session of the two-day meeting of the Eastern Seaboard Conference of the National Negro Congress at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, 132 West 138th Street.

Urging the establishment of a mixed military unit containing both white men and Negroes, a resolution adopted by the conference said such a grouping would enhance the Negroes’ morale, “which is fast waning due to undemocratic conditions in this democratic country.” Such a mixed unit would let Negroes and whites partake together of that democracy for which both are fighting, the resolution declared.

The same resolution pointed to the shortage of manpower in war industries and on the farms and asserted that “in spite of this acute problem there remains virtually an untapped source of manpower, the Negro, who is trained and stands ready to answer the call.”

“We further believe,” the resolution continued, “that the ultimate victory can be won only through the working in unity of all the people in America with full integration of the Negro in our nation’s production forces.”

The delegates urged the establishment of a second land front in Europe and the prosecution of the war until the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis. “We urge that the right of self-determination for all colonial peoples be the stated policy of the United Nations” the resolution continued, “and that the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms be immediately applied to India, Africa, the Carribean and other colonial peoples. “The plight of the Jewish people in foreign countries is the concern of all the United Nations and we therefore advocate that Government of the United States initiate and undertake immediately all possible rescue measures.

“We are unalterably opposed to any force which attempts to disrupt the unity and sympathetic cooperation of this nation with the Soviet Union, China and other members of the United Nations.”

James B. Carey, national secretary and treasurer of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, told a mass meeting that ended the conference that when peace came 35,000,000 men and women might be without work unless a full employment and social security program was enacted.

MAY 1, 1943

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, April 30—Qualifying his statement with a warning “not to attach too much significance to it,” Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox announced at his press conference today that losses from enemy submarine sinkings had been “much lower” in April than during the previous month.

Mr. Knox said he made the statement with his “fingers crossed” and that he did not want anyone to draw overly important conclusions from it “because figures in that type of warfare can—and do—go up and down.”

Nevertheless, April did show an improvement in the Battle of the Atlantic, and the Secretary of the Navy said he shared the hope of Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, that the submarine menace would be brought under control within four to six months.

Sinkings in March had been higher than in the previous two months, Mr. Knox said, but he declined to disclose the percentage of the improvement in the month just ending.

“During the past four months,” he commented, “we have added steadily to the number of surface craft and aircraft being used to combat submarines.”

Commenting on the fact that United States merchant ship losses in the Pacific from submarine action were practically nil, Mr. Knox explained that the Japanese used their submarines for entirely different purposes—service with the fleet, patrol duty and observation, and so forth.

In the Pacific the situation was somewhat reversed in comparison with the Atlantic, for there it was American submarines that were taking the toll of warships and merchant vessels, he said.

There had been no evidence yet that the Japanese were using their developing air bases in the Aleutian Islands, Mr. Knox asserted.

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, 1942.

By WALTER W. RUCH

Special to The New York Times.

WILKES-BARRE, Pa., May 1—The en-tire anthracite field in Eastern Pennsylvania was made idle today by a walkout of about 80,000 miners who remained unmoved by the announcement that the Federal Government had taken control of the mines which they quit last midnight at the expiration of their contract.

Not a shovel of coal was turned in the hard coal region, forming a rough triangle bounded by Scranton, Sham-okin and Pottsville, and it was obvious that the miners were looking toward New York rather than Washington for the cue to return to work.

Although the miners were looking forward to President Roosevelt’s radio address tomorrow night, their leaders who were available for comment declared that nothing he could say would induce the men to resume operations Monday morning.

The only thing that could persuade the men to return, these leaders said, would be word from New York that a new contract had been signed or that the old one had been extended, with wage provisions retroactive to April 30.

There was no disorder in the hard coal field during the day. The men simply failed to appear for work, many of them turning up later on the street corners instead in their Sunday best to discuss the action they had taken.

Spokesmen at the union headquarters in the three hard coal districts of the United Mine Workers of America reported this morning that everything was down tight and not a wheel was turning.

The only ray of hope visible to mine leaders here was the fact that the U.M. W.A. representatives and the operators had resumed their negotiations in New York this morning and might reach some basis for a settlement.

Union leaders were reluctant to discuss the strike, choosing that word should come from New York, and those who did so insisted that their identity be withheld. One of these was a member of the scale committee of the U.M.W.A. who returned today from New York to make a survey of the situation in this field.

This man, regarded in the area as a conservative, insisted that the miners now were 100 per cent behind John L. Lewis and would turn a deaf ear to pleadings or orders to return to work in the absence of a new contract or an extension of the old one.

“These men won’t go back to work without a contract,” he said.

“They will not accept a promise from the government or from anyone else. They will only be satisfied when the anthracite operators put their John Hancocks on the agreement.

“I do not expect any change in the situation as a result of the President’s address tomorrow night. All the President can do is to ask the men to go back to work and guarantee them protection. This will be meaningless.”

He said that the members of the scale committee had been directed to remain in their respective fields until the international officers of the union had worked out an agreement with the operators.

“When and if that is done, the international officers will summon the scale committee back to New York to approve the agreement,” he added. “If a contract is signed then, work will be resumed.”

Soldiers with an anthracite miner in 1943.

By CRAIG THOMPSON

Special to The New York Times.

PITTSBURGH, May 2—A large part of the 125,000 bituminous coal miners in this area tonight heard the news that will send them back into the mines, discontinuing a stoppage that had already resulted in the United States Government taking over the operations of the mines.

In some small communities they gathered in knots around radio sets through which they heard the speech of President Roosevelt.

More important to them, however, was the announcement of John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers Union, that a fifteen-day truce pending further negotiations, had been agreed to by him and Harold L. Ickes, Fuel Administrator.

Through a day of waiting while they listened to radio news bulletins on the movements of Mr. Lewis; they had been grimly determined not to return to their jobs unless Mr. Lewis told them to. After he had authorized a return on Tuesday—apparently deferring resumption of operations an extra day so as to give local union leaders an opportunity to notify the full membership—many of them appeared ready to report for the shift beginning at 7 A.M. tomorrow.

It was not believed possible to get the mines in full operations before Tuesday morning, or possibly Monday evening. Meanwhile, the miners had accepted a decision by Mr. Lewis, although impressed by the President.

The miners had taken a pretty bad beating from public opinion in this area and were smarting under it. At a little place called Library, near here, about fifty had assembled in the local fire-house around the radio. When reporters showed up to watch their reactions and to report the manner in which they received the decision the men ordered them out.

In other places there was a small amount of criticism directed against Mr. Lewis and a great deal directed against the President. Although some of the miners appeared to have been moved by what the President said, they were determined to string along with Mr. Lewis and said so.

It developed fairly rapidly that the full resumption of operations would involve meetings of the local unions and a ratification of the truce, which was expected to take up most of tomorrow.

During the day while they waited to be told what to do, the miners had been determined that they would not call off the strike unless ordered to do so by Mr. Lewis.

Last night in his radio address the President said: “Tomorrow the Stars and Stripes will fly over the coal mines. I hope every miner will be at work under that flag.” This flag was raised over the Pittsburgh Coal Company at Pricedale Pa., on the day the miners walked out.

How much they might have been influenced by President Roosevelt had not a truce been reached became an academic matter, but there were signs that he probably would not have swung much weight.

MAY 9, 1943

When the United Nations troops march across Europe on the final stages of their journey they may carry with them maps showing where buildings with a historic or artistic interest are located and where paintings and other cultural treasures are likely to be found. So much is indicated, though not precisely stated, in the announcement of a committee formed by the American Council of Learned Societies under the chairmanship of Dr. William Bell Dinsmoor of Columbia University. The committee has been in existence since January, working quietly and not putting out any superfluous information.

The nature of its problem is obvious enough. It is also obvious that the problem has military as well as artistic phases. How much is a museum or a cathedral worth in terms of human life, if that question has to be answered? Shall such an edifice be bombed or shelled if it happens to adjoin a railway station or fortified point? Or shall infantry flow around it at greater human cost? We don’t suppose Dr. Dinsmoor’s committee wants to say, but the generals will wish all the information they can get. Another aspect of the subject is the discovery and identification of looted works of art. The Nazis in a thousand years would create nothing worth crossing the street to look at, but as thieves they show some discrimination.

One thinks of all the centuries of Europe: the Romanesque, the Gothic and the Renaissance; the builders of Notre Dame and Chartres; the genius of stone-cutters flowering in the day’s work; the painters of religious ecstasy and tavern vulgarity; the masterless men who plied their noble trades in the shadow of tyranny and war; the young who dreamed dreams, the old who saw visions; the passion and revolt which expressed themselves, not in blood but in creation; the growth of a majestic continental culture through slow generations, out of multitudinous lives. This is the foundation on which the future will have to be built. The future will be surer if the visible objects remain. Dr. Dinsmoor and his colleagues can play as significant a role as the generals do.

By SIDNEY SHALETT

HEADQUARTERS ARMY AIR FORCE OF APPLIED TACTICS, Orlando, Fla., May 15—After nearly a year of sparring, the American landing at Attu Island on Tuesday finally elevated the North Pacific theatre from the side-show category and raised the curtain on a great forthcoming battle. At last American forces are in contact with the Japanese in the North Pacific and the issue is joined.