June–July 1944

While an estimated 350 correspondents waited patiently in London for news that the invasion of France had begun, Herbert Matthews of The Times was with the U.S. Fifth Army ducking German bombs and snipers while battling into the suburbs of Rome. By June 4 the Italian capital was in American hands. This symbolic triumph was overshadowed two days later when the news blackout imposed in Britain was finally lifted. Just after dawn on June 6, a fleet of 7,000 ships and landing craft of all sizes, supported by 12,000 aircraft, transported the first American, British and Canadian troops—more than 130,000 in all—across the English Channel to five beaches in Normandy. The news first reached The Times in New York City from the German broadcasting service just after midnight. Ninety minutes later, the paper was on the street, the first announcement of the invasion the world had been anxiously awaiting. A few hours later General Eisenhower released a formal communiqué, but it was brief and short of hard facts.

Although The Times sent seven newsmen ashore in Normandy, reports of the battle lacked real detail. The Times used the first week of the campaign to renew its enthusiasm for the liberation of France. “The love of France,” claimed one editorial, “of the French culture, of the French landscape is shared by all civilized men.” Among the first reports, “The Europe We Came to Free” declared that Europeans were “hungry and rebellious,” alternately animated by “hope, depression and exaltation.” The struggle to free them went more slowly than anticipated, “Hedge to Hedge” as one headline put it.

The beachhead was well-established by mid-June and by June 26 the port of Cherbourg was captured by General Omar Bradley’s forces. But the city of Caen, opposite Montgomery’s British and Canadian forces, was strongly defended; when the Germans finally withdrew to a line south of the city, a British assault, code-named “Goodwood,” failed to dislodge them. To make matters worse, on June 13 the German secret weapon, long threatened by Goebbels’s propaganda, became real. The first V-1 “flying bombs”—unmanned cruise missiles—landed on London, the opening of an assault in which 10,000 bombs were fired, though only 2,419 reached the British capital. Not until the end of July was the deadlock in Normandy finally broken, a week after a group of senior German army commanders had tried unsuccessfully to assassinate Hitler and seize power. Hitler remained in control, ordering fanatical resistance in France as German forces grew weaker. On July 25 Bradley finally unleashed Operation Cobra for a breakout from Normandy toward the port of Avranches. The German Front crumbled at once, the start of a two-week retreat that left much of France in Allied hands.

The news from France once again eclipsed battles elsewhere. In Belorussia the Red Army mounted one of the largest operations of the war, code-named “Bagration,” against German Army Group Center, the major front in the East. It began on June 22, when 2.4 million soldiers, 31,000 guns and 5,200 tanks smashed forward into the German line. Unlike Normandy, the Soviet offensive worked like clockwork. Minsk was captured by July 4, and Brest-Litovsk, where German forces had launched Barbarossa three years before, on July 26. Army Group Center was destroyed. That summer the German Army lost 589,000 men in the East, the biggest defeat inflicted on German armed forces.

Progress was also rapid in the Pacific,. On June 15 American forces stormed ashore on Saipan in the Marianas, supported by a huge fleet that included fifteen aircraft carriers. The Japanese responded by sending a large task force with nine carriers to intercept the invasion. The Battle of the Philippine Sea began on June 19, the largest carrier-to-carrier engagement of the war. The result was a decisive defeat for the Japanese Fleet. Despite Japanese successes in China in the so-called Ichi-Go offensive, on July 20 General Hideki Tojo resigned as premier, following his country’s defeats in the Pacific. By the end of July not only Saipan but also Guam was in American hands.

In the United States, President Roosevelt was named the Democratic Party’s candidate for president for an unprecedented fourth term with The Times now in support of his candidacy. Arthur Sulzberger thought Roosevelt was more likely to guide the nation to “ultimate victory” than any other choice.

By HERBERT L. MATTHEWS

By Wireless to The New YorkTimes.

ROME, June 4—The Allies’ troops fought their way into Rome this morning and at nightfall they were still fighting on the outer edges, which the Germans were defending despite all their protestations about considering Rome an open city. Other large German units faced entrapment south of Highway 6 unless they could be pulled back across the Tiber or through Rome.

But Rome has been reached—the goal of conquerors throughout the ages, though none was ever before able to make the almost impossible south-north campaign. What Hannibal did not dare to do, the Allies’ generals accomplished, but at such a cost in blood, matériel and time that it will probably never again be attempted.

Early today Rome was just a few yards in front of us and a road sign, “Roma,” faced us tantalizingly. On the other side the Allies’ first tank to penetrate Rome proper was blazing fiercely, while a German self-propelled gun, some tanks and machine-gun snipers held up the triumphal entry into the greatest prize of the war thus far. Here is the story of our getting to that point.

It was the break-through on the Fifth Army’s right wing yesterday that did the trick. That thrust into the mountain ridge behind Velletri three days ago that permitted the flanking of Rocca di Papa cooked the Germans’ goose. Faced with the certainty that their positions along the coast would be quickly flanked, the Germans fell back swiftly to positions just before Rome, playing desperately and successfully for time until darkness had fallen. Meanwhile their right wing began falling back, but they are going to lose plenty, for they have delayed overlong.

Evidently they underestimated the Allies’ drive. They started massing tanks north of Highway 6 to throw against our advancing columns, but they could not even get those up in time.

Mark Clark, Commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, rides through Rome following the liberation of the city in June 1944

Correspondents started for Rome at 5 P.M. yesterday. Divisional headquarters were moving so quickly that we had trouble finding the one that we wanted. There they told us that their force was moving quickly.

Prisoners were filing back by the dozens. The Hermann Goering Armored Division was really steam-rollered this time, but everyone available was thrown in, even veterinaries, in the vain effort to stem the Allies rush.

We knew that there would be strafing, bombing and perhaps shelling by dark, but we had to get up there on Highway 6. A three-quarter moon was a blessing, just as it was the night before we took Messina. There was an eerie tenseness in the air as darkness came on. We got over the Alban Hills in the dusk and our eyes searched vainly through the haze for Rome, which, we knew, lay on the Campagna right before us. Excitement had gripped everybody, but it was a grim, silent and deserted countryside, except for our advancing columns.

Our little jeep wound in and out among the cars and soon we reached the infantry filing along both sides of the road. The wounded were coming back steadily, and so were the prisoners, but otherwise this was like all the roads that led to Rome, not far away.

Every moment we expected the Germans to react, but still we kept going. At Kilometre 18, dead bodies began cluttering the landscape—ours as well as theirs. Suddenly we struck a clear patch and rushed on alone through the darkness, almost holding our breaths. But we knew that there were some reconnaissance units ahead and perhaps the way into Rome was clear, after all.

At last we reached the leading reconnaissance unit; “You’d better watch out,” an officer said. “You’ve come through lots of Jerries. They’re all over these fields and there’s nothing up here except armored cars.”

Kilometer post 13 was right there. That meant that we were little more than ten miles from the center of the city and five miles from the outskirts. A tank fight was going on just a mile ahead, the nearest that our forces were to reach during the night. There was a little side road to a group of three houses. We went in there, and none too soon. Within a few minutes we heard the German planes come over. They took their time, tantalizingly flying around and around to get their bearings. An important crossroads was only 100 yards away, and we knew that we were in for it

They began dropping flares. Then came strafing, then bombs. We flattened ourselves on the floor of the peasant’s stone house. One flare dropped next to it and, for what seemed like ages, we dug our heads into the ground and held our breaths, waiting and waiting. And then it came. Two bombs crashed beside the house, which shook dizzily as plaster fell from the ceiling.

Only then did we learn that the farmer had built a refuge just outside the house and we dashed into it. There we were relatively safe. Within a few minutes, four jeeps loaded with ammunition dashed up. The men jumped out of them and into our refuge. Then began a strange night.

We were surrounded by Germans, and we knew it. We dared not move. Two soldiers came in with us, while their comrades went up the hill to another refuge.

Acrid smoke still filled the refuge, coming from the bombs that had been dropped almost squarely on it. Outside, more armor was trundling down the highway. This gave us some comfort, but our worry was the Germans who had been left behind, scattered in the fields.

Somehow the night dragged its weary length. A peasant woman heated us some water for our coffee, which we hastily downed. Then we went on.

Tanks with infantry were now ahead of us. Tough, bearded, dirty youngsters sat astride them as we passed, again aiming for the head of the column.

The peasants were beginning to line the roads, but they were not cheering, as they had done before Naples. They were stolid and curious. Rome was being conquered again, but they showed no emotion at first. Then, as we got nearer to the outskirts, enthusiasm began to rise and a few peasants threw flowers at the tanks.

It was 6:30 A.M. and we were almost at the head of the column. Two tanks were in front of us and there at last was the road sign, “Roma,” just at a bend in the highway.

The first tank clanked around it and then came a crash and a vivid flash as it was hit by an 88mm. shell from a self-propelled gun that had undoubtedly been waiting. The tank driver was killed and two others were wounded. Everybody else dashed for the ditches. The infantry deployed and went forward.

Civilians were foolishly running into and out of their houses, oblivious to danger but scattering wildly when shells came over. Then a sniper got going. He could not have been there before, but now he had a bead on us with a machine gun straight down the road.

This will be a great day in history, but one would not have thought so from the demeanor of the Romans and the strangely peaceful sounds of Sunday morning in the spring. Church bells tolled and even a wedding procession walked solemnly to one church within range of the German guns. A train chugged and whistled along the tracks inside the city. An Italian rode up on a bicycle, not even hurrying as snipers’ bullets whined overhead.

JUNE 5, 1944

By The United Press.

NAPLES, June 4—The Fifth Army captured Rome tonight, liberating for the first time a German-enslaved European capital. German rear guards were fleeing in disorganized retreat to the northwest.

Except for the railway yards, smashed by the Allies’ bombs, the city is 95 per cent intact, United Press correspondents reported after their arrival in the city.

Late tonight, the British Eighth Army, rushing into Rome from the southeast along the Via Casilina, was reported to be joining the Fifth Army in close pursuit of the hard-pressed enemy remnants, under orders to destroy them to a man if possible. Only enough troops to maintain order and ferret out any German snipers or suicide nests were to be left in Rome as the Allies’ main armies pounded on without pausing to celebrate their greatest triumph, coming 270 days after the start of the Italian campaign.

At the very gates of Rome, the Germans had made a final stand but Lieut. Gen. Mark W. Clark, after having waited three hours for the enemy troops to withdraw in accordance with their own declaration of Rome as an open city, ordered a violent anti-tank barrage. Then masses of Fifth Army men and weapons crashed into the city and began mopping up enemy snipers and a few tanks and mobile guns trying to cover the retreat.

More of the enemy survivors of the Allies’ whirlwind offensive were streaming in congested retreat to the northwest at the mercy of the Allies’ planes, which, during the day, destroyed or damaged 600 enemy trucks and other vehicles. The Germans’ jammed traffic columns stretched fifty-five miles to Lake Bolsena.

Direct radio contact with American correspondents in Rome was established tonight. A United Press reporter said that the main entry into the city had been made along the Via Casilina, which passes through the Porta Maggiore at the southeastern edge of the city. Other Allied troops were reported to have fought their way through the Ostiense freight yards, just south of St. Paul Gate, the main entrance to the city from due south and only one and one-quarter miles from the Venice Palace.

The entry into Rome came with dramatic suddenness after the Allies, spear-headed by American armored forces, had shattered the last German defenses below the city in the Alban Hills. The final advance covered almost fifteen miles in twenty-four hours and was so rapid along the last miles that large pockets of Germans were believed to have been cut off. There was a furious battle in the workers’ district, where the Germans fought from streets and buildings before their ranks broke.

The final breakthrough, the result of an overwhelming assault by the Allies’ arms, came in the twenty-four hours beginning on Saturday evening. After having outflanked enemy strong points in the southern Alban Hills the Allies smashed through those formidable peaks and burst out on the plain before Rome. They then drove on into the city.

By FREDERICK GRAHAM

By Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, June 4—As nearly as can be determined there are more than 350 assorted British and American newspaper, magazine and radio correspondents and photographers in the European theatre of operations now waiting to cover the coming invasion. Most of them are men and the majority of them represent the three major news agencies and daily newspapers.

Correspondents who have been in this theatre for two, three or even four years seem to have absorbed the wisdom of patience—or maybe it is the British wartime diet that makes them appear patient as they wait for the invasion. A good many in this category have put down roots of a sort here. Admittedly these roots usually are pretty shallow but, even so, the correspondents appear to be in no high fever to tear them up and follow an invasion that may be less pleasant, comfortable and convenient than London.

Correspondents who have been here one year or short of two years appear no more impatient to get the invasion under way than their older colleagues.

The newcomers—those who have been here from three to six months—hardly give the impression that they are all keyed up, either. Most of them are still getting used to wearing a uniform and taking salutes from misled G.I.’s.

Many of these never had been outside the United States before and would like to see more of London before leaving it. They want to see France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, too, but they would prefer to see Britain before moving on.

Correspondents, like military police, seem never to travel alone. In pairs or larger groups you see them almost everywhere in London: in small local pubs, in the cocktail lounges of swank West End hotels and in the bars of scrubby Bloomsbury, in pubs and restaurants around Fleet Street and in the better Mayfair establishments.

The better-known correspondents—the “name” correspondents—and those representing the well-heeled publications can usually be found in the costlier and more exclusive bars and eating places. But there are enough correspondents who have tough expense accounts and less than magnificent salaries to provide business in great measure to the smaller and cheaper ones.

War correspondent Frank Gillard at work in early 1944, during a mock battle to rehearse the reporting of the D-Day landings for BBC radio.

JUNE 5, 1944

By Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, June 4—Germany’s synthetic oil industry, which has become the Wehrmacht’s mainsource of supply since Rumania’s Ploesti oil fields were bombed, was crippled in three days of operations in May by the Eighth United States Air Force.

During these three days the Zeitz plant, twenty miles south of Leipzig, was put out of production indefinitely. Other plants at Poelitz, outside Stettin, and Bruex, in Czechoslovakia, were so badly damaged it is unlikely they will be able to resume production.

Five other synthetic oil factories at Merseburg, Magdeburg, Bohlen, Lutz-kendorf and Ruhland were badly damaged by attacks.

In addition American bombers and fighters destroyed 343 enemy fighters. On May 12, 150 enemy planes were shot down, on May 28, ninety-three, and on May 29, 100.

Of the thousands of American aircraft dispatched to these targets, 145 were lost.

In the attack on Poelitz, on May 29, large fires broke out throughout the plant and smoke rose to a height of more than 10,000 feet.

Zeitz was even more heavily hit. Building after building was either blasted flat or burned out.

By RAYMOND DANIELL

By Cable to The New York TimEs.

SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCES, June 6—The invasion of Europe from the west has begun.

In the gray light of a summer dawn Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower threw his great Anglo-American force into action today for the liberation of the Continent. The spearhead of attack was an Army group commanded by Gen. Sir Bernard L. Montgomery and comprising troops of the United States, Britain and Canada.

General Eisenhower’s first communiqué was terse and calculated to give little information to the enemy. It said merely that “Allied naval forces supported by strong air forces began landing Allied armies this morning on the northern coast of France.”

After the first communiqué was released it was announced that the Allied landing was in Normandy.

German broadcasts, beginning at 6:30 A.M., London time, [12:30 A.M. Eastern war time] gave first word of the assault. [The Associated Press said General Eisenhower, for the sake of surprise, deliberately let the Germans have the “first word.”]

The German DNB agency said the Allied invasion operations began with the landing of airborne troops in the area of the mouth of the Seine River.

[Berlin said the “center of gravity” of the fierce fighting was at Caen, thirty miles southwest of Havre and sixty-five miles southeast of Cherbourg, The Associated Press reported. Caen is ten miles inland from the sea, at the base of the seventy-five-mile-wide Normandy Peninsula, and fighting there might indicate the Allies’ seizing of a beachhead.

[DNB said in a broadcast just before 10 A.M. (4 A.M. Eastern war time) that the Anglo-American troops had been reinforced at dawn at the mouth of the Seine River in the Havre area.]

[An Allied correspondent broadcasting from Supreme Headquarters, according to the Columbia Broadcasting System, said this morning that “German tanks are moving up the roads toward the beachhead” in France.] The German accounts told of Nazi shock troops thrown in to meet Allied airborne units and parachutists. The first attacks ranged from Cherbourg to Havre, the Germans said.

[United States battleshipsand planes took part in the bombardment of the French coast, Allied Headquarters announced, according to Reuter.]

The weather was not particularly favorable for the Allies. There was a heavy chop in the Channel and the skies were overcast. Whether the enemy was taken by surprise was not known yet.

Not until the attack began was it made known officially that General Montgomery was in command of the Army group, including American troops. The hero of El Alamein hitherto had been referred to as the senior British Field Commander.

In his order of the day, made public at the same time as the first communiqué, General Eisenhower told his forces that they were about to embark on a “great crusade.”

The news that has been so long and so eagerly awaited broke as war-weary Londoners were going to work. Hardly any of them knew what was happening, for there had been no disclosure of the news that the invasion had started in the British Broadcasting Corporation’s 7 o’clock broadcast.

Even the masses of planes roaring overhead did not give the secret away, for the people of this country have grown accustomed to seeing huge armadas of aircraft flying out in their almost daily attacks against German-held Europe.

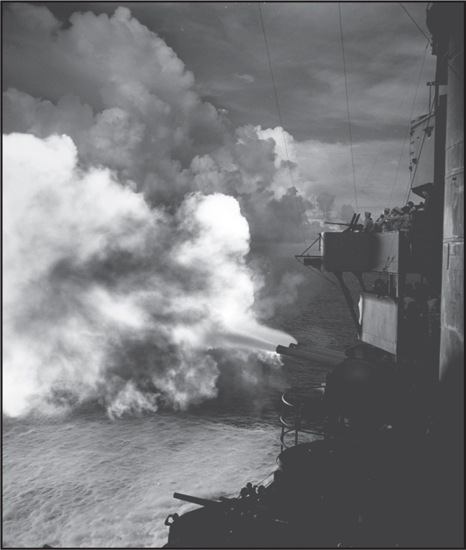

Details of how the assault developed are still lacking. It is known that the huge armada of Allied landing craft that crept to the French coast in darkness was preceded by mine sweepers whose task was to sweep the Channel of German mine fields and submarine obstructions.

Big Allied warships closed in and engaged the enemy’s shore batteries.

Airborne troops landed simultaneously behind the Nazis’ coast defenses.

An array of sea craft at Omaha Beach, Normandy, during the first stages of the Allied invasion.

Special to The New York Times.

WASHINGTON, June 6—Washington learned officially of the invasion of Europe at 3:32 A.M. today when the War Department issued the text of the communiqué issued by the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces.

This flash was the climax of three hours of tense waiting that followed first German radio reports that hostilities off France had begun. Before that both the War Department and the Office of War Information said they had no information to confirm or deny the German reports.

The communiqué was handed newspaper men in the War Department by Maj. Gen. Alexander D. Surles, chief of the Army Bureau of Public Relations. With the communiqué was issued a statement by General of the Armies John J. Pershing which declared the sons of the American soldiers of 1917 and 1918 were engaged in a “like war of liberation” and would bring freedom to people who have been enslaved.

The capital awakened rapidly after the initial broadcasts. Lights flashed on and radios began to blare. Newspaper men hurried to their offices. Everybody was demanding to know whether it was “official.”

If the White House was aware of the report, there was no outward indication. Only a few lights glowed there and the customary guards patrolled up and down monotonously.

Only a few hours earlier—at 8:30 P.M.—Mr. Roosevelt had addressed the world for fifteen minutes on the fall of Rome.

By 1:45 A.M., almost the entire public relations staff at the War Department had reported for duty.

Elmer Davis, director of the OWI, met about half a dozen news men in his office about 4 A.M. and told them the OWI had no assurance that the invasion was coming off this morning but thought that it might be. He said that OWI did not put out any of the German broadcast reports prior to official confirmation from General Eisenhower’s headquarters.

Between the official flash and the time General Eisenhower began his talk, the OWI was transmitting the text of the communiqué.

JUNE 7, 1944

By RAYMOND DANIELL

By Cable to Tax New York Times.

LONDON, June 6—This was D-day and it has gone well.

At daybreak Anglo-American forces dropped from the skies in Normandy, swarmed up on the beaches from thousands of landing craft and renewed the battle for France and for Europe, broken off four years ago at Dunkerque.

And when darkness fell, on the word of no less than Winston Churchill, the King’s First Minister, who is still this country’s best reporter, they had toeholds on a broad front and were fighting as far back from the coast as Caen, which is eight and a half miles behind the Channel beaches and 149 miles from Paris.

At the time he spoke the Prime Minister said that the battle which was just beginning was progressing in “a thoroughly satisfactory manner.” But even he, like most people in this island, had his fingers crossed.

The Germans’ resistance until now has been surprisingly, perhaps ominously, slight. Several obstacles to any amphibious operation have been surmounted. The concentration of ships has escaped serious bombardment from the air and the huge armada has crossed the Channel without encountering real enemy naval opposition. Submarine obstacles and shore batteries, which had been pounded relentlessly by the Allied air forces, were less lethal than had been expected.

The weather was uncertain but possibly a decisive factor. It was not favorable to the attacking forces. It was revealed at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force that the great blow had been postponed one day because the barometer had started to fall—not an unusual occurrence in this land of fickle weather.

On the basis of reports from his meteorologists, General Eisenhower postponed the launching of his attack twenty-four hours. Then the weather men assured him that an improvement was coming and he was faced with the problem of gambling on their science or postponing the attack another month. His was a grim decision, for it waslearned at Supreme Headquarters that had the meteorologists been wrong the whole expedition might have met with disaster.

As it was, the weather was not good, but it improved. At the start clouds obscured air targets and winds swept the Channel into one of its hellish moods, so a large part of the invading force must have been seasick when they landed to do battle with the enemy.

The tides of the Channel, which in the days of the Spanish Armada favored England, changed in the crucial hours between dark and daylight. Minesweepers had to switch their gear from one side to the other and never slow down or stop lest the cutting tools they drag behind them sink to the ocean floor.

The first communiqué merely said Allied troops had landed in northern France. Later this was expanded unofficially to mean Normandy, where the apple trees have just shed their blossoms and begun to bear fruit.

U.S. troops disembarking from landing crafts during the D-Day invasion, June 6, 1944.

The attempt at liberation of the Continent has begun auspiciously. Later the Allies will count upon the help of the resistance movements of Europe, but radio broadcasts by Gen. Charles de Gaulle, head of the French Committee of National Liberation; Dr. Pieter S. Gerbrandy, Netherlands Premier; Hubert Pierlot, Belgian Premier, and General Eisenhower have made it clear that the time is not yet. All these speakers advised the people of occupied Europe to wait for orders to rise against the Nazi occupation.

JUNE 9, 1944

Two great phases of history are unfolding today on the new Western Front. One is the destruction of the Nazi power. We cannot come to grips with that power today on the soil of Germany itself. We must encounter it first on the soil of France, where if we could avoid it we would not shatter one ancient wall, cut down one tree or trample a single poppy under foot. The love for France, for the French culture, for the French landscape, is shared by all civilized men. It is pitiful that we must hurt what we love in order to kill what we hate.

This awful necessity must burden everyone in authority, from President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill down to the company commander who has to open fire on a Norman farmhouse in order to clear out snipers. If it so weighs on us, how heavy must be the burden on all true Frenchmen. No doubt freedom is greater than Paris and honor outbalances even a village whose houses may have seen Joan the Maid pass by. But we should have reverently in mind the agony that is mingled at this moment with French hopes.

And surely the two great Governments which are chiefly responsible for Allied military and political policy in France should go as far as they possibly can to spare the feelings of those Frenchmen, in and out of France, who did not surrender in 1940. Some progress has indeed been made toward full cooperation with the French Committee of National Liberation. General Eisenhower and General de Gaulle are now “in complete agreement on the military level.” That is good news. But military agreement is not sufficient. As soon as battle conditions permit we shall want and need to hand over liberated French territory to Frenchmen, To what Frenchmen shall we hand over the guardianship of French soil until the French people themselves by popular choice have created a new Government? Obviously to those, both inside and outside of France, who have been loyal to their country and to liberty.

We do not believe there is any basic difference of opinion on this score either in Washington or in London. Yet there has been a shocking lack of preparation for this political emergency. There may have been good reasons for our present uncertain policy toward the National Committee, but, if so, they have been kept inexcusably secret.

Our soldiers need the eager support of every French civilian. How much easier would their task be if there could now be awakened in France the spirit that brought the Marseillaise marching to Paris in 1792! The Fourth Republic is about to be born in fire and pain. Cannot it be welcomed into the world with something more stirring than a businesslike agreement between two generals?

By Cable to The New York Times.

SUPREME HEADQUARTERS, Allied Expeditionary Force, June 10—A “commando” raid by a group of civilian scientists, a search through obscure seventeenth–eighteenth-century French manuscripts, months of study of geological reports, experiments with model beaches—all these were a part of the Allied preparations for the invasion of Normandy that is one of the most remarkable stories of the war.

Months before the invasion parties of civilian scientists, not all of them young or signally muscled, landed on the beaches up which the Allied infantry were to scramble last Tuesday. Wriggling along on their bellies, within range of German guns, they obtained samples of sand soil so when the tanks and trucks bustled ashore the drivers would be prepared for the terrain and equipment would be on hand to bridge the worst spots.

The dramatic story of the preparations, which began in musty libraries, shifted to laboratories and ended on the shell-swept beaches, was told today by a mild-mannered professor in baggy clothes.

When the invasion was planned he was consulted by the Allied staff on the character of the beaches. He referred the officers to the old manuscripts, which, he said, stunned the staff officers. “But I convinced them they were worth studying so we went to work,” he said.

“The geologists expected trouble because the area had been an Ice Age forest,” the scientist added. “But the military people did not like all this book talk. So the only thing to do was to go and see.”

Photographs and pre-war reports helped in the study of the beaches, but the final investigation had to be carried out on the spot. According to the scientist, a few months before the invasion “some very bright lads got over nicely and quietly by night, causing no disturbance and attracting no notice.

“They crawled half a mile on their bellies on the beach, with special instruments taking samples and charting the positions of the soft clay patches on the beaches, then brought the results to England.”

With the samples to go on, the scientists recommended the type of vehicles that could best be used on the beaches and marked the points where steel carpets would have to be laid over the soft spots. Then the team of scientists got to work on the enemy’s beach defenses. These were copies, and the experiments showed the troops how they could best be dealt with on landing.

Most of the defenses were reconstructed from photographs and other intelligence reports.

In the same painstaking manner the scientists assembled data on flooded areas around Carentan. Every scrap of information was gathered. Here, too, there were manuscripts to be studied as well as military references to the Frenchflooded area in the Franco-Prussian War seventy-four years ago.

Carentan lies in the center of the whole series of tidal river valleys. By the simple process of openingthe sluice gates at high tide andclosing them at low tide, the Germans converted the entire area into a mass of shallow lakes and ponds.

JUNE 11, 1944

By PIERRE MAILLAUD LONDON

(By Wireless).

What kind of Europe are the Allied armies going to discover as they penetrate the areas of German conquests in Western Europe? One may well say “discover” rather than “rediscover,” for long years of ordeal have wrought such deep changes that even former visitors to the old Continent won’t be able to retrace their steps on once familiar paths.

To such a Europe there is no available Baedeker. Its national traditions, beliefs, basic ways of living, even its frontiers, have all been thrown back into the melting pot. The old molds have been broken; Europe has refused to be cast into the new German one. Nothing quite similar has happened in history since the tenth century, when, through the dismemberment of Charlemagne’s empire, the first European framework was shattered and the Continent fell back on feudal anarchy.

Our contemporary Europe, to be sure, had several hundred years of national traditions behind her, but these traditions, deep-rooted in the West, were less settled in eastern and Balkan Europe, where frontier and minority feuds had never ceased and have lately been deliberately fanned by the Germans. In the West the foundations of social life and many tenets of national life have been shaken. For more than four years Europe has existed chiefly on negative sentiments—hatred of German rule and a burning will to free herself from the German yoke.

This is not to say there are no currents of thought, no political tendencies, no valuable trends of social evolution, no ethical life in shackled Europe. That would be far from the truth. But there is no means of coordination among these diverse tendencies so that the general pattern of the Continent is infinitely variegated and confused not only to the onlooker but equally so to the citizen of any occupied nation who cannot communicate either in thought or deed with his fellow countrymen or his fellow Europeans. From tales of the experiences of travelers, fugitives and combatants one can form a general picture of the Continent. Let us paint it in broad strokes:

It is a hungry, rebellious, touchy, hypersensitive welter of peoples, among whom all contradictions can coexist and even be somewhat reconciled or merged. It is idealistic in its long-term aspirations, often cynical in the attempt to satisfy its daily needs. It believes in man’s future, yet often sets little store by human life. Large sections of the population cling to past memories as antidotes to present sufferings, while iron-hard groups of resistance live only for the future in ruthless indifference to their own temporary plight or their own lives.

It is apt to be parochially nationalistic in its sentimental reactions, through years of national humiliation, yet its hopes are broadly European and even world wide. Its men and women folk, who queue up for hours for a few ounces of bread and live for days on end on the single obsessive thought of getting food, suddenly stake their own and their children’s lives on an act of defiance of the enemy or charity to a friend. They chafe under Allied bombings, if they feel they have more than their share, but they will take any risks to save an Allied pilot.

Hunger, hope, depression and exaltation, the overpowering pressure of daily needs, acts of utter self-denial, contrasts between the urgency of the small problems of life and the general yearning for great accomplishment, contradictions between the narrowness of the day-today outlook and the broadness of long-term conceptions which is the reaction against moral and intellectual servitude, greed and generosity, brutal realism and idealism—such are the elements of the European make-up. It is at once soft and hard. Life is spasmodic. Such a Europe, for which emergency has become a habit, is in many respects incalculable. In it the largest allowances must be made for the unexpected.

More than any other event in history, the invasion will be, above all, for better or for worse, a meeting between peoples on which lasting impressions will be formed. This is not to suggest that responsibility for the consequences will lie solely with Allied soldiers and not with the continental peoples as well.

But it must be realized that humiliated nations are nationally touchy, that their pride has been deeply hurt, that anything suggestive of a patronizing attitude toward them would touch a very sore point. They are purchasing at a very high cost the right of being treated as equals.

What inferiority complex the western nations of the Continent may therefore have suffered since June, 1940, has been largely redeemed by their share in the struggle, both in the internal and external theatres of war. British and American soldiers will find themselves among people who will be oversensitive to their behavior for good or evil.

It is impossible for the average American citizen, or for that matter for the British, to form an approximate picture of the appalling misery inflicted, and inflicted with ruthless and perverse deliberation, by the German invader. To cause enduring, and if possible irreparable, damage to the body and soul of Europe was, and still is, a part of the German—and not only the Nazi—policy. So that under-feeding, destitution, political and literal slavery have been dominant notes in the lives of the occupied peoples for more than four years. The spectacle of physical fitness, relative abundance and freedom which their allies will present, in striking contrast to the continental plight, will therefore be all the more welcome if it is not coupled with the display, conscious or not, of superiority in wealth or conduct.

Readers may, perhaps, find the above picture too gloomy, or feel that if the outlook of the occupied nations is such as I have tried to describe it, it shows a degree of ingratitude. They must, however, understand that nations cannot endure appalling physical and moral sufferings without finding some compensatory element This can only be found in the hardening of national pride, which in itself entails a strain on relationships with others—including friends.

To take this into account and turn the present operations into a reunion of peoples as well as a military victory is the great ambassadorial task not of statesmen only but of every citizen-soldier who sets foot on the Continent. No task was ever worthier, nor its fulfillment more fatefully decisive.

JUNE 14, 1944

By E. C. DANIEL

By Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, June 13—At one of the touchiest moments of the war, it still takes an average of only eleven minutes apiece for invasion news dispatches to be read and censored by the three-nation military censorship at Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

These dispatches are pouring through London at the rate of 500,000 to 750,000 words a day. Front-line dispatches generally consist roughly of 300-word “takes,” or sections, each.

On the stroke of D-day, the special SHAEF censorship force representing the United States, Britain and Canada and the ground, sea and air forces was at “action stations” in London. Sixteen field censors with three radio transmitters crossed the Channel with the fighting forces to handle dispatches under fire.

They had received not only full training in censorship but also field training to fit them for the rigors of the front, and they had thoroughly studied the organization, personnel and secret weapons of the invasion units about which the correspondents would be writing. Several of them served in Africa. The censors have already started functioning and news dispatches are being sent by wireless from the beachhead to London, ready for immediate publication or transmission overseas.

At headquarters the news censorship consists of a vast enlargement of an American organization that has been functioning for months as an advisory and auxiliary body to the highly geared press censorship operated by the British Ministry of Information since the beginning of the war. The SHAEF censorship, which does not cover political matters, is a branch of the Supreme Headquarters public relations department, under a British officer, Lieut. Col. George Warden, formerly a military adviser to the British censorship. He has as his operations officer an American, Lieut. Col. Richard H. Merrick, who was for several months the United States Army censor inthis theatre.

Colonel Merrick commands an organization with the unwieldy name of “SHAEF Joint Press Censorship Group.” Its battleground is known to every correspondent as“Room 16” in the Ministry of Information Building. Its personnel consists of 138 censors, including the sixteen in the field, from the British, American and Canadian armed services.

The censor makes any necessary emendations, stamps the copy “Passed for publication as censored,” and marks it with his initials and number. The dispatch is then returned to the senior censor, who, if he has time, inspects it for too much or too little censorship. Of fifty representative dispatches recently passed—dispatches of all types and lengths—it was found that two minutes was the shortest time for censorship and thirty-eight minutes was the longest. This record can be expected to improve as the first rush of dispatches subsides and the censors become more familiar with the material.

Dispatches written in the London offices of American newspapers and news agencies and sent to cable companies for transmission in the usual routine are referred, usually by telephone, to the SHAEF censorship if they contain disputable points about operations in France. The censors at the cable companies are the same British censors who have functioned there for years, augmented by eighteen American censors “lent-leased” to the British for the rush.

JUNE 16, 1944

By GEORGE F. HORNE

By Telephone to The New York Times.

PACIFIC FLEET HEADQUARTERS, June 15—American troops who fought their way ashore on Saipan Island in the Marianas Islands on Wednesday have firmly established their beachheads and are making good progress in an advance inland against heavy opposition, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz said in a communiqué tonight.

The enemy is fighting bitterly and has attempted several counter-attacks with tanks, but they have been broken up by our troops with the support of aircraft and warships lying offshore. Thus the most important battle fought so far in the Pacific offensive, now reaching to within 1,465 statute miles of Tokyo and a threat to the Japanese homeland itself, was going well for the invaders.

Tonight’s communiqué was the second of the day issued by Admiral Nimitz. The first confirmed previous Japanese reports that Saipan was being invaded.

American Marines attack Japanese defensive positions during the Battle of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, 1944.

Tonight’s communiqué follows: Assault troops have secured beachheads on Saipan Island and are advancing inland against artillery, mortar and machine gun fire. Virtually all heavy coastal and anti-aircraft batteries on the island were knocked out by naval gunfire and bombing. Our troops have captured Agingan Point. In the town of CharanKanoa brisk fighting is continuing.

The enemy has attempted several counter-attacks with tanks, but these attacks have been broken up by our troops with the support of ships and aircraft.

In general, fighting is heavy, but good progress is being made against well-organized defenses.

In the earlier announcement Admiral Nimitz told how under cover of supporting bombardment by air and surface forces, following an unprecedented four-day battering of Saipan and other islands throughout the Marianas group, our forces were still pouring ashore. He said reports thus far indicated that our casualties in the initial stages were moderate.

The first assault troops went in yesterday and were supported in their battle on the beachheads by a naval bombardment maintained all last night.

Saipan is the largest island central Pacific forces have ever assaulted and perhaps the best defended, for it is believed to have been reinforced with materiel and fighting men in recent months. The Japanese, obviously aware of the stakes involved, are going to defend it bitterly and they are in a position to inflict severe punishment on landing forces.

There is no question that the operation is the most important yet staged in the central Pacific area. Because of the land mass involved—Saipan is twenty and three-quarters miles long and five and one-half wide with an area of seventy-five square miles—and the heavy defenses, it will be the scene of the first encounter between large numbers of amphibious attackers and large numbers of land troops of the enemy’s army.

Its importance is heightened by the proximity to Japan itself and the fact that victory will bring at an early date the next phase of the crushing of Japan, concentrated air attacks by land-based bombers from all sides. Possession of Saipan would bring to the enemy with shocking emphasis the realization that the final phases of our advance are near at hand.

It would sever communication lines with its many bases eastward and to the south and leave to the withering process thousands upon thousands of men and tremendous quantities of materiel that Japan cannot afford to lose.

The effect upon the morale of the Japanese people cannot fail to be staggering.

Coming with the bombing of Japan itself by land-based Superfortresses, the assault in the Marianas, if it is as successful as it is expected to be, will be difficult for the enemy propagandists to explain away and to convert by their own special type of sophistry into another Japanese victory.

JUNE 16, 1944

By SIDNEY SHALETT

Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

WASHINGTON, June 15—The air war against the heart of the Japanese Empire has begun, the War Department announced this afternoon. B-29 Superfor-tresses of the new Twentieth Air Force, which is part of a new “super-air force” under the personal command of Gen. H. H. Arnold, bombed Japan today, a special communiqué revealed.

There are three epochal factors in the announcement:

First, that the monster B-29, half again as big as the Flying Fortress, is in operation.

Second, that the type of aerial attrition that reduced Germany to the stage where an invasion of Europe could be launched has commenced against Japan proper.

Third, that, in creating the Twentieth Air Force, a special organization that is not subject to the jurisdiction of any theatre commander, the Joint Chiefs of Staff have set up what virtually amounts to a separate air force.

The importance of this new phase of the Pacific war was emphasized by statements from Gen. George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, who termed it the beginning of “a new type of offensive against our enemy”; from General Arnold, commanding general of the AAF, who declared it was “the fruition of years of planning for truly global warfare,” and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, who asserted that the action had “shortened our road to Tokyo.”

The history-making communiqué was confined to the following bare statement, personally handed out by Maj. Gen. Alexander D. Surles, War Department Director of Public Relations, at 1:39 o’clock this afternoon:

“B-29 Superfortresses of the United States Army Air Forces Twentieth Bomber Command bombed Japan today.”

No details of where we struck the enemy, or how hard we hit, were revealed, although it was understood that the War Department would release this information as quickly as it felt the story might be told without imperiling security.

While the War Department did not disclose the location of the necessarily huge bases from which the “Superforts” flew, it was revealed by James Stewart, Columbia Broadcasting System Far Eastern correspondent, in a broadcast from Washington today, that the B-29’s had flown from “somewhere in West China.” Mr. Stewart, recently returned from Chungking, said the B-29’s “took off and landed on Chinese bases” constructed entirely by the hand labor of 430,000 Chinese farmers.

Additional historical significance was added to the bombing, our first air attack on Japan proper since the small-scale raid on April 18, 1942, by carrier-based planes led by Lieut. Gen. (then colonel) James H. Doolittle, by the fact that it occurred on the same day that American landings on Saipan in the Marianas, another step on the road to Tokyo, were announced.

For once the Tokyo radio failed to beat us in announcing the news of the B-29 raid. The Tokyo radio was on the air twenty minutes after the War Department told the story, but it talked only about its version of the Saipan landings. Elmer Davis, Office of War Information director, congratulating the Army both on bombing Japan and “scooping” the enemy on the story, suggested that the Japanese might be “trying to cook up a story that will gloss over their losses.”

A B-29 Superfortress, 1944.

JUNE 17, 1944

By RAYMOND DANIELL

By Wireless to THE New York Times.

LONDON, June 16—For the last twenty-four hours parts of England south of a line drawn from Bristol to The Wash have been bombarded intermittently by robots. Most of the night and in daylight these one-ton bombs with wings and engines but no pilots have sailed in to blow up in haphazard fashion.

There is little doubt that this is Adolf Hitler’s “secret weapon.” In fact the Germans say it is. This is their answer to the breach that Anglo-American armies of liberation have made in their Atlantic wall, but whether it was dictated by a spirit of revenge or by necessity, providing some comfort for their own suffering people, is speculative. Maybe it is a combination of both, but the military value of the new weapon remains to be proved.

In announcing to the public several hours before the Germans got around to it that the Nazis were using their secret weapon at last, Home Secretary Herbert Morrison advised the country to carry on with its war work until danger was imminent and to duck as fast as possible when the broken thrumming of one of Hitler’s newest engines of destruction ceased and its light died out.

“There is no reason to think that the raids will be worse than, or indeed, as heavy as the raids with which the people of this country are familiar and which they have borne so bravely,” he said.

There is something a little eerie and unsettling about the idea of 2,000 pounds of TNT whizzing around the sky with no direct human control, but after the experiences of these peoples with the indiscriminate bombings in 1940, that idea can be accepted with reasonable equanimity.

These veterans of the air raids knew last Tuesday night that the war in the air had entered a new phase, although security considerations kept their newspapers from telling them so. When Mr. Morrison announced in the House of Commons today that this country was being bombarded by pilotless aircraft sent into the air by Germany, everyone breathed more easily. That was something everyone could accept even if he did not understand it.

The robot planes first made their appearance in the skies over southern England on Tuesday night. They were so few and the evidence was so scanty it was decided to keep silent and let the enemy show his hand. That he did last night to a point where silence had lost its virtue. So, with admirable timing. Mr. Morrison made his statement.

Since it seems likely that the Germans guide their gadgets on some sort of radio beam it is interesting to note that tonight the British Broadcasting Corporation announced that its programs were liable to interruption or cancellation without notice.

Pinpointed in searchlights, the Germans’ new toy looks a little like a miniature fighter plane. It flies on an undeviating course at about one thousand feet and gives a telltale glow from its tail. Its engines, which have an ominous, rhythmic throb, die out a few seconds before the whole mass plunges to earth and explodes with a terrific lateral blast.

These infernal flying machines are believed to be designed for launching from a roller coaster, like tracks suddenly halted on the upgrade, so they are airborne at a terrific speed and at an altitude of about two hundred feet

They seem to attain an altitude of 1,000 feet or so and hold it until they blow up either by accident, design or contact.

Last night the Germans sent along a small number of ordinary bombers, apparently to observe and report where the mystery missiles were landing.

JULY 2, 1944

By The Associated Press.

CHUNGKING, China, July 1—The Japanese have launched their long-expected general offensive northward from the Canton area, the Chinese High Command announced tonight, with the enemy making an effort to join with forces driving down the Canton-Hankow railway through battered Hunan Province which, if successful, would be a disaster for the Chinese.

The general northward advance began in Kwangtung Province June 28, the Chinese said, reporting that heavy fighting was in progress along the route. The invaders lunged forward in striving to accomplish the juncture with their forces at Hengyang, about 225 miles from the Japanese-held Canton area and ninety-five north of the Kwangtung border.

An unconfirmed report said Japanese forces had landed on the coast of Fukien Province and were heading for Foochow, a few miles inland. Such a landing might be another Japanese move to prevent an American landing on the China coast and to neutralize all Allied air bases between the coast and the Peiping-Hankow and Canton-Hankow railroads.

There also was an unconfirmed report of a Japanese landing at Pakhoi, on the southwestern coast of Kwangtung, which might presage a thrust through Kwangtung into Kwangsi Province.

The High Command, aware of the gravity of the situation, was known to be rallying forces for a stand to prevent a junction of Japanese forces, but doubts were expressed openly as to ability of the Chinese to arrest the onslaught.

In the new drive from the Canton area, first three, then six Japanese columns were reported to have driven northward, their main weight apparently thrown in the direction of the important highway and river junction of Tsingyun, about 110 miles south of the Hunan Province border. This offensive began a few days before the Chinese mark the beginning of the eighth year of hostilities on July 7.

The Chinese High Command claimed battered Hengyang, vital rail junction of the Canton-Hankow route, with lines to Kwangtung and Kwangsi to the south, still was in Chinese hands. Evidently fighting raged within the city.

A rail station apparently has fallen to the slashing attack by three Japanese divisions besieging the city, for a communiqué of Lieut Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell’s headquarters told of its bombing by American planes. Two days ago a Stilwell headquarters bulletin reported American bombs had been hurled against Japanese positions at Hengyang.

Junction of enemy forces with the Hengyang troops would give the Japanese virtually complete control of 1,000 miles of railway north and south all the way from Peiping through Honan, Hupeh, Hunan and Kwangtung Provinces to Canton. Such an unbroken rail route would solve the supply problems of the Japanese, heretofore dependent upon sea lanes and river and overland routes, all open to attack.

It also would slice China in two, sealing the eastern coast against the eventuality of American landings, and appeared to be aimed at the same time at neutralizing established American air bases in the country.

The Chinese claimed to have smashed another Japanese attack, this one from Chekiang Province, and aimed at supporting the drive in Hunan, 300 miles to the west, and to have seized the enemy base of Chuhsien, about twenty-five miles east of the Kiangsi border.

This drive, the Chinese said, had been knifing westward along the Chekiang-Kiangsirailway. The High Command said all positions taken by the Japanese since they began the campaign June 11 had been retaken, and that more than 4,000 of the invaders had been killed, including a brigade commander, Maj. Gen. Takahiku Yokoyama.

American planes struck savagely throughout the Hengyang battle area in a wide radius, slashing at Japanese river transport, troop and cavalry concentrations, gun emplacements and installations, in an effort to stem the enemy drive along the railway.

JULY 4, 1944

By HAROLD DENNY

WITH THE AMERICAN FORCES, In France, July 5—Today’s fighting in this sector was just hard slugging for small gainsagainst stiffening German resistance.

Almost everywhere on our twenty-five-mile front it was a continuation of the hedge-to-hedge fighting. Our men were digging out their cunningly concealed enemies.

The Germans were making much use of bicycles for troop movements to counteract the interference with the rail-ways and the apparent shortage of motor transport or gasoline.

Daily we see the highways from which fighting has been heard dotted with dead Germans lying near their bicycles. The French are gathering these cycles and we see them everywhere pedaling along the roads.

A curious and fortunate feature of the fighting on this front is the scarcity of German artillery. The Germans gambled on dive-bombers to take the place of field artillery in the beginning of the war. They subordinated the manufacture of artillery and the training of artillery staffs. Now that the Allies have mastered the German dive-bombers and have gained command of the air, the Germans are badly outclassed in supporting fire for infantry. A considerable amount of the enemy artillery that our forces have overrun is captured Russians guns. Around La Haye du Puits, however, they had massed a number of guns. As they had direct observation over the town’s northern approaches, they raked the roads and our infantry positions. Their artillery is manned entirely by real Germans, in contrast to the impressed troops in many of their infantry units.

The path of our troops who got into La Haye’s railway yards today and of the others who swung around the town from the west was hard all the way yesterday afternoon and today. The enemy threw seven tanks against our men west of La Haye late yesterday.

While two of them made a demonstration to draw our fire, the five others lay hull-down behind a ridge and raked our men in the open fields with machine guns. Our forces rushed anti-tank guns into action, however, and drove the German tanks off.

Another brisk fight last night raged around a farm near Denneville. Our forces finally drove out what Germans were still alive. Our troops were finding many mines, though often they had been hastily laid. One variety appearing now is the “mustard pot,” which can blow a foot off any unwary soldier.

The crew of an American long-range large-calibre artillery piece and a mischievous American fighter pilot had sport this morning with a German command post that had been discovered last night. Today this gun made a direct hit on the building housing the German staff. The Germans came boiling out and started to flee in a command car.

The fighter pilot, seeing this, dived down and machine-gunned the car. It careened off the road and smashed against a stone wall.

By DANIEL T. BRIGHAM

By Telephone to The New York Times.

GENEVA, Switzerland, July 2—Information reaching two European relief committees with headquarters in Switzerland has confirmed reports of the existence in Auschwitz and Birkenau in Upper Silesia of two “extermination camps’’ where more than 1,715,000 Jewish refugees were put to death between April 15, 1942, and April 15, 1944.

The two committees referred to are the International Church Movement Ecumenical Refugee Commission with headquarters in Geneva and the Fluchtlingshiie of Zurich, whose head, the Rev. Paul Voght, has disclosed a long report on the killings.

This report says national “clean-ups” are periodically ordered by the Nazis in various occupied countries and when they are enforced Jews are shipped to the execution camps. Totals compiled two months ago show the following number of Jews “eradicated” in the two camps, excluding hundreds of thousands slain elsewhere:

Poland |

900,000 |

Netherlands |

100,000 |

Greece |

45,000 |

France |

150,000 |

Belgium |

50,000 |

Germany |

60,000 |

Yugoslavia, Italy and Norway |

50,000 |

Bohemia, Moravia and Austria |

30,000 |

Slovakia |

30,000 |

Foreign Jews from various camps in Poland |

300,000 |

To this total must now be added Hungary’s Jews. About 30 per cent of the 400,000 there have been slain or have died en route to Upper Silesia. Discussing “malicious, fiendish, inhuman brutality” in the treatment of Hungarian Jews, the Ecumenical Commission says:

“According to authenticated information now at hand, some 400,000 Hungarian Jews have been deported from their homeland since April 6 of this year under inhuman conditions to Upper Silesia. Those that did not die en route were delivered to the camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau in Upper Silesia, where during the past two years, it has now been learned, many hundreds of thousands of their coreligionists have been fiendishly done to death.”

After a fortnight to three months’ imprisonment, during which they were “selected” or worked to death, the Jews were led to the execution halls, it was said. These halls consist of fake bathing establishments handling 2,000 to 8,000 daily.

Prisoners were led into cells and ordered to strip for bathing. Then cyanide gas was said to have been released, causing death in three to five minutes. The bodies are burned in crematoriums that hold eight to ten at a time. At Birkenau there are about fifty such furnaces. They were opened March 12, 1943, by a large party of Nazi chiefs who witnessed the “disposal of 8,000 Jews from 9 o’clock in the morning until 7:30 that night,” according to the report.

JULY 5, 1944

The Nazis continued yesterday to fish for information regarding the whereabouts of Lieut. Gen. George S. Patton Jr. and the American seventh Army.

A German DNB broadcast for the European press outside Germany, reported by United States Government monitors, speculated that General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, Allied ground commander, intended “to coordinate resumption of large-scale operations with employment of a United States Army group under General Patton.” DNB said “it can be expected” that this group will attack “another sector of the Atlantic front in the very near future.”

“The group may attack the adjoining sector between the Seine and the Somme, the Pasde Calais area, or the Breton Peninsula, the occupation of which must be a very tempting prize to the Allied High Cornmand,” the Nazi broadcast continued. “Possession of Brest would provide them with another deep-sea port.”

JULY 10, 1944

By GEORGE F. HORNE

By Telephone to The New York Times.

PEARL HARBOR, July 9—The furious battle for Saipan is over after twenty-five days. “Our forces have completed the conquest,” Admiral Chester W. Nimitz announced this morning.

The Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet said that the island was secured yesterday afternoon.

“Organized resistance ended on the afternoon of July 8, West Longitude date, and the elimination of scattered disorganized remnants of the enemy force is proceeding rapidly,” he stated.

The battle lasted nearly a month, including the preparatory carrier-aircraft assaults and pre-invasion bombardments. It was on June 10, before dawn broke over the Western Pacific, that the first attack began. For four days the well-entrenched defenders of Saipan, estimated at 20,000 to 30,000 Japanese troops, and other enemy garrisons and defense installations from Tinian to Rota, Guam and Pagan were shattered by powerful carrier-plane raids or bombardment by the big guns of the surface fleet, in some cases both.

The marines stormed ashore on Saipan’s western beaches to come finally to grips with the largest and strongest enemy force yet encountered in the Central Pacific offensive. The end came sooner than observers here had expected, for only yesterday the Admiral disclosed that an enemy counterattack had plunged through our left flank for a distance of 2,000 yards. It was one of the bitterest battles and casualties on both sides were believed to have been heavy.

And at the last report yesterday we had regained only about a third of the lost ground.

Apparently, however, the troops on the western anchor of our line advanced rapidly again, slashing forward north of Tanapag town to retrieve the losses and carry the battle forward to the island’s northeastern extremity.

Meanwhile, on the right flank marine forces advanced to their objective.

No official announcement has been made of the number of enemy prisoners taken, but it will probably be small, for the Japanese have fought all the way through with their traditional fanaticism and determination to stand or die. It can be assumed that the majority of the garrison was wiped out.

Up to the middle of last week our own forces had buried nearly 10,000 Japanese.

For our part the story of Saipan will live as one of sacrifice, for the price paid has been in keeping with the importance of the island to us. There has been no announcment of our casualties since June 30, when Admiral Nimitz disclosed that 1,474 Americans had been killed between June 14 and June 28.

Our total casualties, including dead, wounded and missing up to that date, were 9,752.

Admiral Nimitz said later he expected our losses would be relatively smaller in the final stages of the battle, and it is likely that they were during the next ten days, for we had then taken commanding positions, we had captured much material and supplies and had given the enemy fatal blows.

Nevertheless, the significance of the casualty lists should not be overlooked, particularly by those who may be inclined to misinterpret our unbroken roster of victories from the Gilberts to the Marianas. Before the seizure of Tarawa and Makin back in November the island-spotted sea stretching toward Japan looked discouragingly wide and probably few people dreamed we would go so far so fast.

At Saipan we are 1,465 statute miles from Tokyo and although the end is in sight there is still many a bitter story to be told.

Possession of strong air and sea facilities in the Marianas will, as Admiral Nimitz explained, permit us to employ our sea strength relatively near to the heart of Japan.

And then perhaps, when the entire inner defense of the enemy falls within the arc of which the Marianas form the center, sea and air power can be brought to bear on the enemy’s homeland from the north through the Kuriles and from the Asiatic mainland whence the mighty Superfor-tresses are already beginning to come. Admiral Nimitz and Gen. Douglas MacArthur can batter at arm’s length against the Philippines, against Japan itself, and against the China coast where Pacific forces will land for the final stages.

JULY 13, 1944

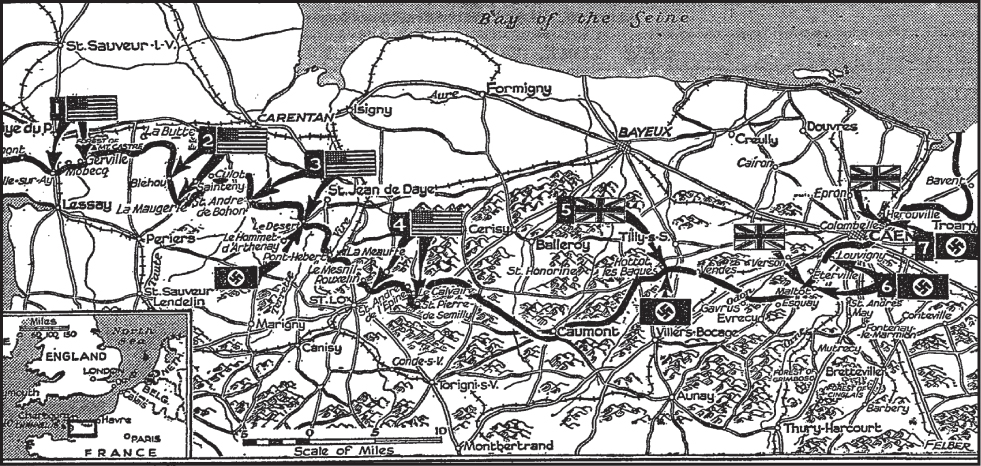

A grinding advance toward Lessay carried the Americans to Angoville-sur-Ay and gave them possession of the entire Forest of Mont Castre (1). Although they were still four miles from the Feriers junction they widened their spear-head by taking Blehou (2). A German counter-attack forced our troops out of Le Desert, but to the west they occupied most of St. Andrés de Bohon (3).

As one American column smashed to a point one and a half miles from St. Lo, another “began outflanking the junction by seizing St. André-de l’Epine, Le Calvaire and St. Pierre-de Semilly (4). Heavy fighting raged near Hottot les Baques (5). Around Caen the British repelled attacks southwest and the Germans clung to recaptured Louvigny (6) and battled for Colombelles (7).

Premier General Hideki Tojo’s “entire Cabinet” has resigned, the Japanese Domei agency announced last night in a wireless dispatch to Japanese-occupied areas.

The dispatch, reported by the Federal Communications Commission to the Office of War Information, quoted a statement by the Japanese Board of Information.

The Japanese announcement said that “it has been decided to strengthen the Cabinet by a wider selection of the personnel.”

“By utilizing all means available the present Cabinet was not able to achieve its objective.” the statement declared.

It said that “the Government has finally decided to renovate its personnel totally in order to continue to prosecute the war totally.”

The announcement came a day after Tojo had been divested of his concurrent post as Army Chief of Staff in continuation of a Japanese High Command shake-up that began two days ago.

Last night’s Domei dispatch carried this introduction:

“Tojo’s Cabinet resigns: Premier Tojo’s Cabinet took a resolute step on July 18 and effected the resignation of the entire Cabinet.”

A Domei transmission last night at 11 o’clock [Eastern War Time] to newspapers in Japanese-occupied areas, said that on July 18 the Emperor had ordered Marquis Koichi Kido, Home Affairs Minister, into audience, with a view to forming a new Cabinet.

Marquis Kido, who, as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, is the highest adviser to the Japanese Emperor, called a meeting of former Premiers the evening of July 18 to deliberate on the personnel of the succeeding Cabinet, Domei said.

One Domei broadcast, referring to the Cabinet resignation, said:

“The reason, to put it straightforward, is that the individuality of the Tojo Cabinet was unable to keep up with the intensity of the burning war spirit of the people. The Board of Information announcement was issued July 20 (Japanese time). No explanation of the delay in making known the resignation was offered immediately.

The board’s announcement follows:

Since the outbreak of the (Greater East Asia) war the Governmenthasbeen cooperating closely with the Imperial Headquarters as one unit and has exerted every possible effort for the prosecution of the war.

At present, in face of a grave situation and realizing the necessity of a strengthened personnel in time of urgency for the prosecution of the war, it has been decided to strengthen the Cabinet by a wider selection of the personnel.

By utilizing all means available the present Cabinet was not able to achieve its objective; here, then the Government has finally decided to renovate its personnel to continue to prosecute the war totally and, having recognized the fact that it was most appropriate to carry out a total resignation of the Cabinet, Premier Tojo gathered together the resignations of each member of the Cabinet and presented them to the Emperor on July 18 at 11:40 A.M. (Japanese time) when he was received in audience.

At this time of decisive war, to have reached the stage existing today is causing the Emperor much concern, because of which the present Cabinet is filled with trepidation, and in apologizing for the Government’s meager power to the men on the fighting front and the 100,000,000 people of Japan who continue to work towardcertain victory, it has been decided that this Cabinet should be dissolved.

Thus, for the purpose of assuring a successful prosecution of this war, we anticipate with great anxiety the appearance of a new strong Cabinet at this time without loss of opportunity.

Meanwhile, Japanese propagandists, in their output for domestic and overseas consumption, continued to focus attention on the loss of Saipan as a means of whipping up the people’s fighting spirit. The propagandists appealed for still greater efforts on the “production front” and urged the Japanese to achieve a “protracted war,” dismissing any ideas of a war of comparatively short duration.

Tojo, known among his colleagues as the “razor blade” because of his sharp tongue, held office since the fall of the Konoye Cabinet Oct. 17, 1941, and headed the Government that ordered the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

JULY 21, 1944

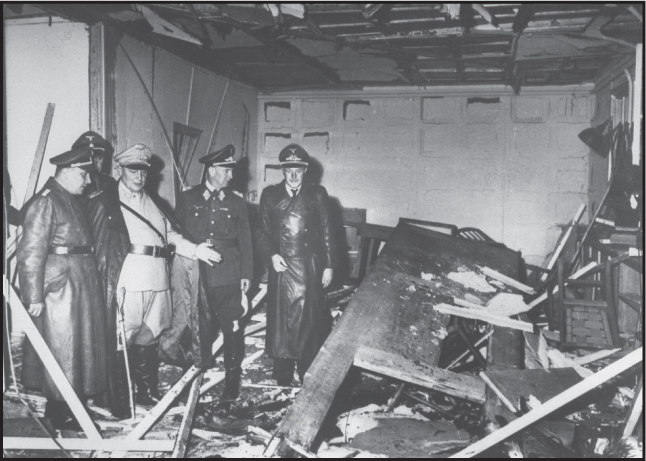

Adolf Hitler had a narrow escape from death by assassination at his secret headquarters, the Berlin radio reported yesterday, and a few hours later in a radio broadcast to the German people he blamed an “officers’ clique” for the attempt to kill him. His address disclosed a movement in the armed forces to overthrow him and his regime. He announced that a purge of the conspirators was under way.

Thirteen members of his military staff were injured, one fatally and two seriously, by a bomb set off at an undisclosed place while many of his highest advisers were assembled around him. The man who played the role of assassin, Hitler said, was Colonel Count von Stauffenberg, one of his collaborators, who stood only six feet away from him as he hurled the bomb. Von Stauffenberg is dead, Hitler announced.

Waiting to see Hitler before the assassination attempt was Benito Mussolini. Reich Marshal Hermann Goering, who rushed to Hitler’s side, was in the immediate vicinity. Hitler escaped with singes and bruises.

While Dr. Joseph Goebbels and Nazi radio propagandists at first tried to put the blame for the attempt to kill the Fuehrer upon the Allies, Hitler himself exploded the bombshell by announcing that the culprits were a group of German Army officers. He thus confirmed reports of a serious rift between the Nazi High Command and German military elements.

In his broadcast, recorded by the Federal Communications Commission, Hitler told the German people: “If I address you today I am doing so for two reasons: first, so that you shall hear my voice and know that I personally am un-hurt and well, and, second, so that you shall hear the details about a crime that has no equal in German history.

“An extremely small clique of ambitious, unscrupulous and at the same time foolish, criminally stupid officers hatched a plot to remove me and, together with me, virtually to exterminate the staff of the German High Command. “The bomb that was placed by Count von Stauffenberg exploded two meters [slightly more than two yards] away from me on my right side. It wounded very seriously a number of my dear collaborators. One of them has died. I personally am entirely unhurt apart from negligible grazes, bruises or burns.

“This I consider to be confirmation of the task given to me by Providence to continue in pursuit of the aim of my life, as I have done hitherto. … “In an hour in which the German Army is waging a very hard struggle there has appeared in Germany a very small group, similar to that in Italy, that believed that it could thrust a dagger into our back as it did in 1918. But this time they have made a very great mistake.” Hitler concluded by saying that the “criminal elements” would be exterminated ruthlessly. He spoke for only six minutes, shrieking in maniacal rage as he described the circumstances of the attempted assassination that nearly killed him and his entire staff.

He said that the annihilation of what he called the criminal clique behind the attempted assassination would give to Germany the “atmosphere” that the front and the people needed.

That the attempt to kill him was coupled with efforts to provoke a report in the German Army was indicated in Hitler’s address when he called upon German troops and civilians to refuse to obey the orders of the men he called “usurpers” and to kill them. He revealed also that Heinrich Himmler, his Minister of the Interior and chief of the Gestapo, had been put in charge of the home front army, with special powers to deal with the emergency. The vesting of Himmler with special powers even beyond the authority he already enjoys was taken as an indication that Hitler and his immediate Nazi entourage were squaring off for a possible life and death struggle with the Army.

How serious was the clash between the Nazi ruling circle and the “usurpers” of whom Hitler spoke was evident also from his statement that “accounts would be settled in a National Socialist manner” with his enemies in the armed forces.

Hitler’s own characterization of the situation compared it to 1918, when Germany was making her last vain effort to hold back the deluge. He spoke of the “stab in the back,” a slogan he used so successfully in stirring up the German masses against the Weimar Republic, whose leaders he had accused of bringing about the German defeat in World War I by undermining morale and letting down the armed forces in the field. The specter of 1918 hovered ominously over Germany in yesterday’s developments.

A telephone dispatch from The New York Times bureau in Berne, Switzerland, last night noted that telephone communications between the Reich and the outside world had been cut since midnight Tuesday. All attempts to reach the Reich by telephone through neutral quarters last night received the answer “gespert”—closed.

After Hitler, Doenitz and Goering had spoken on the radio a mysterious broadcast was picked up in London on the Frankfort wavelength by a “Wehrmacht officer” who appealed to like-minded men to help “save our cause.”

JULY 21, 1944

KANSAS CITY, July 20 (AP)—The 91-year-old mother of Senator Truman does not want her son to be Vice President. She believes he should stay in the Senate where “he can do more good.”

“His investigating committee is doing fine work,” she said. “He ought to stay there.”