1919–1939

On June 28, 1919 in the Hall of Mirrors in the French Palace of Versailles, outside Paris, a treaty was signed between the victorious Allied powers and Germany, bringing World War I to an end. American President Woodrow Wilson hoped that the treaty would pave the way for a new world order based on peace, disarmament and the freedom for peoples to choose their own destiny. Only twenty years separated the end of the first war and the start of a second war that was even more destructive and global. The roots of that second conflict can be found in the settlement reached in 1919. Alongside the idealistic ambitions for a new, peaceful world order were sown the seeds of a narrow nationalism that spawned a violent, intolerant politics. Even Wilson’s idealism proved short-lived when, in 1920, the Senate rejected ratification of the treaty and effectively took the United States out of the new League of Nations. The League had been established to try to resolve international disputes by rational, peaceable means. Throughout the twenty years that followed, the United States stood aside from any formal commitment to the international order, just as the newly founded Soviet Union, emerging from the wartime Communist revolution of 1917, remained on the international margins. Britain chose to be semidetached from the crises inside and outside Europe, seeking the self-preservation of the Empire and unwilling to run risks that might undermine Britain’s worldwide interests.

This situation was fertile ground for those forces in world politics that had not been satisfied by Wilsonian idealism. Economic downturns and political instability after the war plunged Italy into crisis and prompted a nationalist backlash expressed in the rise to power of Benito Mussolini and his Fascist blackshirts. Appointed prime minister in October 1922, Mussolini had established a tough dictatorship by 1926, with himself as self-proclaimed Duce, or leader. In Germany a post-war crisis was brought on by defeat and the humiliating Versailles Treaty that blamed Germans for the war and made them pay reparations for starting it, stripped away German territory in Poland and France, and forced Germany to disarm. All this generated a hyperinflation that destroyed all savings and at the same time prompted the rise of violent, ultranationalist movements that rejected the peace imposed by the West and pursued the politics of revenge. Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party was among their number, though Hitler was not yet the prominent political figure he was to become. In November 1923 he staged a coup in imitation of Mussolini but it ended in farce with his arrest and imprisonment. It took him almost ten years to establish a broad nationalist movement, animated by a hatred of the Versailles Treaty and the Jews, and a desire to reestablish German military power. In 1933, in the midst of a major economic crisis and political chaos, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, and within months had enacted legislation designed to exclude Germany’s Jewish population from the new “national revolution.” By 1934 he too had become dictator, Germany’s Führer; in 1938 he appointed himself commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

On the other side of the world, Japan also came to reject the settlement arrived at in 1919. Japanese military leaders resented the second-class status accorded to Japan by the other major powers. They saw Japan’s destiny as the leader of a major empire, like that of Britain and France, in a reinvigorated Asia. Frustrated by economic crisis and closed markets abroad, the Japanese Army invaded Manchuria in 1931, and moved on to attack northern China the following year. Step by step, Japan consolidated its position in Asia and when a full-scale war broke out in July 1937 between Japan and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist China, the Japanese declared a “new order” in Asia and tried to compel Europe and the United States to accept the altered balance of power in the region.

Mussolini and Hitler also were attracted to the idea of “new orders” in Europe and Africa, and since none of the League powers had prevented Japanese aggression, they began to undertake their own programs of territorial expansion. In 1935 Italy attacked the African nation of Ethiopia and conquered it by May 1936. In July 1936 Mussolini, together with Hitler, agreed to help the nationalist general Francisco Franco in his bid to seize power in Spain. Later, in the spring of 1939, Mussolini occupied Albania and began to think about further wars to build an Italian empire in the Mediterranean. Hitler tore up the Versailles Treaty by rearming Germany, remilitarizing the Rhineland and repudiating reparations. In March 1938 German troops were ordered into Austria and a so-called “Greater Germany” was created. In the summer of 1938 pressure was put on the Czech government to hand over territory where the majority of the population was German, and on September 30 at Munich, Britain and France accepted German arguments and agreed to transfer the “Sudeten” Germans to German rule, dismembering the Czech state.

Throughout the period when the “new order” states were disrupting the international order, the only states committed to upholding the international order—Britain and France—found their options limited. Neither wanted to risk all-out war because of the terrible human and material cost already revealed in the horrors of WWI. Both had unstable empires, full of nationalists demanding liberation from colonial rule. Both faced economic crises in the 1930s that increased the political risks for democracies if they chose to rearm. But in the end these multiple crises forced the democracies to begin large-scale rearmament, while trying to figure out ways of preserving peace. This strategy of appeasement might have worked if Britain and France had faced reasonable opponents. It was clear by 1939 that there was no possibility of appeasing Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese Army and that war was now likely.

After the occupation of Prague by the Germans in March 1939, the British and French gave a guarantee to Poland that shaped the coming conflict. Hitler wanted Poland to give back the territory the Germans had lost in 1919, and to agree that the city of Danzig (which was under League supervision) should become German again. The Poles rejected this, fearful that they would suffer the fate of Czechoslovakia. Throughout the summer the British made it clear that any aggressive move by Germany would be met with force. On August 23 Hitler suddenly signed a pact with the Soviet Union guaranteeing non-aggression between the two countries. He was convinced that this freed him to attack Poland and seize the territory he wanted. He was also convinced that the West would back down. His war was a gamble on the timidity of the democracies. Though he could not know it, when he ordered the attack on Poland on September 1, he had launched World War II.

By WALTER DURANTY

VERSAILLES, June 29.—There could have been found no nobler setting for the signing of peace than the palace of the greatest of French kings, on the hillcrest of Versailles. To reach it the plenipotentiaries and distinguished guests from all parts of the world, who motored to their places in the Hall of Mirrors, drove down the magnificent, tree-lined Avenuedu Chateau, then across the huge square—the famous Place d’Armes of Versailles—and up through the gates and over the cobblestones of the Court of Honor to the entrance, where officers of the Garde Republicaine, in picturesque uniform, were drawn up to receive them.

It was a few minutes after 2 when the first automobile made its way between dense lines of cavalry backed by a double rank of infantry with bayonets fixed—there were said to be 20,000 soldiers altogether guarding the route—that held back the cheering crowds.

The scene from the Court of Honor where I was standing was impressive to a degree. The Place d’Armes was a lake of white faces, dappled everywhere by the bright colors of flags and fringed with the horizon blue of troops whose bayonets shone like flames as the sun peeped for a moment from behind heavy clouds. Above airplanes—a dozen or more—wheeled and curvetted.

The entrance to the palace courtyard is usually barred by great gilded gates. Today, in the words of the hymn, it was “flung open wide the golden gates and let the victors in,” Up that triumphal passage, fully a quarter of a mile long, between the wings of the palace and the entrance to the Hall of Mirrors, representatives of the victorious nations passed in flag-decked limousines—hundreds, one after another, without intermission—for fifty minutes.

Midway down the courtyard is a big bronze statue of Louis XIV on horseback, and all along its sides are statues of the Princes and Governors, Admirals and Generals, that made him Grande Monarque of France.

Jubilant Parisians take to the streets on the day the Treaty of Versailles was signed, June 28, 1919.

At the entrance, just inside the gates, General Bricker, commander of the Sixth Cavalry Division, was sitting on a splendid chestnut, hardly less immobile than the Great King, save when he flashed his sword up to salute a guest of especial distinction. And, as if to typify the whole scene, there were the inscriptions on the facade of the twin temple-like structures on either side of Louis XIV’s statue: “To All the Glories of France.” It was the supreme dedication of the palace to the greatest day that all its glorious history has known.

One of the earliest to arrive was Marshal Foch, amid a torrent of cheering, which broke out even louder a few moments later when the massive head of Premier Clemenceau—for once with a smile on the Tiger’s face—was seen through the windows of a French military car. To both, as to other chiefs, including Wilson, Pershing, and Lloyd George, the troops paid the honor of presenting arms all around the courtyard.

After Clemenceau they came thick and fast, diplomats, soldiers, Princes of India in gorgeous turbans, Japanese in immaculate Western dress, Admirals, flying men, Arabs, and a thousand and one picturesque uniforms of the French, British, and Colonial Armies.

Once amidst terrific enthusiasm a whole wagonload of doughboys, themselves yelling “their heads off,” drove up the sacred slope of victory, but instead of proceeding right to the entrance swung around the Louis statue in the middle of the courtyard and went out by a side gateway, where the rest of the automobiles also went after depositing their passengers. Ten minutes later a camion laden with British Tommies arrived and got a cordial reception.

Whoever was responsible for it had a good thought, that the rank and file who had suffered and sweated most should share in the glorious finale, and it was everyone’s regret that a load or two of poilus had not equally participated.

It was 2:45 o’clock when Balfour, bowing and smiling, heralded the arrival of the British delegates. Lloyd George was just behind him, for once in the conventional high hat instead of his usual felt.

At ten minutes of 3 came President Wilson in a big black limousine, with his flag, a white eagle on a dark blue ground. The warmth of welcome accorded him bore witness to the place he still holds in French hearts and the people’s appreciation of the stand he took in the past few weeks against altering the treaty in Germany’s favor.

By 3 o’clock the last visitor had arrived, and the broad ribbon road stretched empty between the lines of troops from the gates of the palace courtyard. The Germans had already taken their places—to avoid a possible unpleasant incident they had been conveyed from the Hotel des Reservoirs Annex through the park.

It is impossible to tell what the day meant to the people of Versailles. To them, even more than to the rest of France, it was the wiping out of the ancient stain whose shame they had felt more deeply than any other. At the entrance of the crowded dining hall of the Hotel des Reservoirs the old aunt of the proprietor stood with swimming eyes.

“I saw them dine here,” she said, “on the night before the other treaty. And now this—thank God I have lived for it!” At the ride entrance to the courtyard there was a pathetic incident. An old woman, supported by two sons, one in the uniform of a Major of Chasseurs, the other in civilian clothes, but with an armless sleeve and the Legion of Honor and War Cross ribbons in his buttonhole, came up to the stern guardians and begged admittance, although without a ticket.

Just let me inside the courtyard,” she pleaded. “When the Germans were here a General was quartered in my house. I shared the defeat; let me share the victory.”

The orders were strict and absolute, but for her they made an exception.

JUNE 29, 1919

WASHINGTON, June 28—The following address by President Wilson to the American people on the occasion of the signing of the Peace Treaty was given out here today by Secretary Tumulty:

My Fellow Countrymen: The treaty of peace has been signed. If it is ratified and acted upon in full and sincere execution of its terms it will furnish the charter for a new order of affairs in the world. It is a severe treaty in the duties and penalties it imposes upon Germany; but it is severe only because great wrongs done by Germany are to be righted and repaired; it imposes nothing that Germany cannot do; and she can regain her rightful standing in the world by the prompt and honorable fulfillment of its terms.

And it is much more than a treaty of peace with Germany. It liberates great peoples who have never before been able to find the way to liberty. It ends, once and for all, an old and intolerable order under which small groups of selfish men could use the peoples of great empires to serve their ambition for power and dominion. It associates the free governments of the world in a permanent League in which they are pledged to use their united power to maintain peace by maintaining right and justice.

It makes international law a reality supported by imperative sanctions. It does away with the right of conquest and rejects the policy of annexation and substitutes a new order under which backward nations—populations which have not yet come to political consciousness and peoples who are ready for independence but not yet quite prepared to dispense with protection and guidance—shall no more be subjected to the domination and exploitation of a stronger nation, but shall be put under the friendly direction and afforded the helpful assistance of governments which undertake to be responsible to the opinion of mankind in the execution of their task by accepting the direction of the League of Nations.

It recognizes the inalienable rights of nationality, the rights of minorities and the sanctity of religious belief and practice. It lays the basis for conventions which shall free the commercial intercourse of the world from unjust and vexatious restrictions and for every sort of international co-operation that will serve to cleanse the life of the world and facilitate its common action in beneficent service of every kind. It furnishes guarantees such as were never given or even contemplated for the fair treatment of all who labor at the daily tasks of the world.

It is for this reason that I have spoken of it as a great charter for a new order of affairs. There is ground here for deep satisfaction universal reassurance, and confident hope.

WOODROW WILSON.

NOVEMBER 1, 1922

ROME, Oct. 31—The new Cabinet of Premier Mussolini took the oath of office today before the King, thereby becoming the official Government of Italy, and the Fascisti army, the Black Shirts, commanded by Mussolini, which has surrounded Rome, paraded through the city, 100,000 strong.

A fact which is everywhere favorably commented upon is that Mussolini and his Ministers all wore frock coats and silk hats at the ceremony of taking the oath. It was recalled in this connection that when the Socialists, Turati and Bissolati, visited the King recently they wore soft hats and rough sporting jackets. Mussolini’s action is considered all the more interesting when it is remembered that up to a few years ago he also was a Socialist and a rabid revolutionary. He, however, decided that as he had accepted the monarchy the King should be treated with all the pomp appertaining to the office.

The scene when the ex-Socialist and ex-idol of the revolutionary masses took the oath of allegiance to the King was dramatic. The King greeted each Minister, saying: “I feel that I can hardly congratulate you, as you have a stiff, arduous task before you, but I congratulate the country for having you as Ministers.”

The King read the formula of the oath as follows:

“I swear to be faithful to my King and his legal descendants. I swear to be true to the Constitution and fundamental laws of the State for the inseparable welfare of my King and my country.”

Mussolini, who was standing with the Ministers in a group around him, immediately stepped forward and, raising his outstretched arms, said with a booming voice:

“Your Majesty, I swear it.”

The King was so deeply moved that he embraced Mussolini. Afterward each Minister went through the formality.

When all had taken the oath the King remained for a few moments in conversation with Mussolini, who afterward drove back to his office at the Ministry of the Interior. The Fascisti militia had a hard task restraining an enthusiastic crowd which wished to carry him in triumph through the streets.

Mussolini was early at his office this morning. Exactly at 8 o’clock, the hour at which all Government clerks are supposed to be at their posts, he telephoned to all his Ministers instructing them to have a roll call. Anyone who was not at his desk was severely reprimanded and warned that he would be dismissed at the next offense.

This is the first foretaste of a regime of strict discipline which Mussolini intends to institute throughout Italy. Up to the present time most of the Government offices have been worked on the “double hat” system, whereby each clerk possesses two hats, one of which remains permanently hung on a nail in his office, the other being worn going to and from the office. Whenever anyone went into a Government office in search of a clerk, even two or three hours after the regular opening time, an usher would point out the hat hanging on a nail and say: “He is obviously in the office somewhere because his hat is here. You would better wait.” The authorities have winked at this practice, but Mussolini does not propose to tolerate it. He said to The New York Times correspondent today:

“Italy must wake up to the fact that only hard work can save us from financial and economic ruin. I propose that the Government should begin in showing a good example, and Government clerks will be treated just like any clerk working for a private concern would be treated. If they work and do their duty they will be well treated, but if they are not ready to do what is expected of them they will be dismissed. This new regime will be hard for many of them, but they must realize that times have changed.”

Mussolini also outlined the main points of his policy. As to internal affairs, it may be summed up in three words:

“Discipline, economy, sacrifice,” Mussolini said.

“I have not reached my present position by holding forth visions of an easy paradise, as the Socialists did. All will be ruled with an iron hand. It must be a wonderful testimonial to the patriotism and common sense of Italians that the Fascisti with such a program have the backing of an overwhelming majority of the country. Of course, they will be better off in the end, but our policy will not bear fruit for some time, and in the meanwhile there is going to be suffering.”

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (center, with a sash), leading his first cabinet through Rome’s main thoroughfare, Via del Popolo, during the March of Rome, signifying the onset of fascism, November 1922.

Rome, Oct. 31—Associated Press—One hundred thousand well-disciplined Fascisti marched through Rome from north to south today to the plaudits of a million Italian citizens gathered in the capital from all parts of the kingdom.

Their commander, Mussolini, was the central figure of the procession. Like the others who walked behind, the leader wore the black shirt of the organization. He was bare-headed and in a buttonhole was the Fascisti badge, while on his sleeve were several stripes showing that he had been wounded in the war. Mussolini was surrounded by his general staff, including Signor Bianchi, de Vecchi, a number of generals and several Fascisti Deputies. He walked with a firm step the entire four miles to the disbanding point.

The day broke clear and fine, with one of Italy’s brightest suns lighting the way to Borghese Park as the Fascisti troops, abroad early, proceeded up the Pincian Hill, from Tivoli, Santa Marinella and other places on the outskirts of the city, where they had been camping the last three days.

“It is a Fascismo sun,” said a sturdy young black-shirted peasant from the plains of Piedmont as he led the Piedmont contingent into Borghese Park, where 15,000 Fascisti, representing all the province of the kingdom, from Northern Venetia and Lombardy to Southern Calabria and Sicily, assembled.

With military precision they formed and automatically fell into the places assigned to them—dark-visaged youths, with set, determined faces, upon which shone the light of victory, all wearing the black shirt. The rest of their equipment varied from skull caps to soft felt hats and steel helmets—some of them were without hats—and nondescript trousers, multi-colored socks and shoes that ranged from topboots to dancing pumps. They were armed only with riding crops and bludgeons, one man from Ancona swinging a baseball bat.

Briskly they swung into line to the tunes of innumerable bands, the Roman contingent leading the way along the Pincian Hill Road to the Piazza del Popolo and to the Porta del Popolo, through the Gate of the People into the People’s Square, then marching down the Corso Umberto, Rome’s main street, lined with flags.

Every window was filled with Romans cheering, some showering flowers upon the passing blackshirts, while those in the streets saluted straight-armed from the shoulder, with hands extended toward the west.

Through the heart of the city the process continued, the youths never looking to the right or left, and acknowledging the acclamations and cheers only by singing Fascisti marching songs. Thus they reached the monument of Victor Emmanuel and the tomb of the unknown soldier.

At the tomb each contingent, with banners flying, halted before the imposing monument; then two men from each contingent, one bearing a huge palm, the other a bouquet of flowers, ascended the steps leading to the tomb and deposited them upon it until it was lost to sight beneath the mass of bloom. The firat wreath placed on the tomb was earned by a veteran Garibaldian, nearly- a hundred years old, who was assisted up the steps by two youths whose combined ages totalled less than half his own.

On departing from the tomb the Fascisti proceeded at double-quick up the steep Cesare Battlisti Hill to the Quirinal, where the king appeared on the balcony. He stood at salute, and as each continent arrived the flag was dipped, as before the tomb of the unknown soldier. The King received a great ovation from the assembled multitude.

The Fascisti reformed and marched directly to the station, where fifty trained men capable of transporting from 500 to 1,000 soldiers each, had been held in readiness since morning in accordance with the demobilization order that “every soldier must be on his way home before nightfall.”

A feature of the day was the absence of speeches, the Fascisti leaders having decided, as one of them put it, that they are men of action, not words.

NOVEMBER 11, 1923

BERLIN, Nov. 10 (Associated Press)—Holdup men in Berlin now disdain to take paper marks from their victims. Max Weisse, who was recently held up in the Tiergarten district, was robbed of the money he carried in dollars and pounds sterling, but the holdup man gave the victim back his marks with a “Thank you; we don’t bother ourselves with those any more.”

A German who entered a street car carrying a large suitcase was asked for two fares by the conductor on the ground that he must pay for the case.

“But I can’t carry enough paper money for one fare without it.” the passenger protested as he produced several bundles of paper marks in small denominations from the case.

The conductor did not insist upon the extra fare.

NOVEMBER 13, 1923

MUNICH, Nov. 12.—Adolf Hitler, leader of the recent revolt, was arrested last night at Essina, forty miles from Munich. His only injury is a grazed shoulder, said to have been suffered by throwing himself on the ground too energetically in his desire to take cover when the Nationalist forces were fired on by Reichswehr troops in Odeonsplatz on Friday.

The news was common property in Munich this morning, but Dr. von Kahr’s newspaper, the Münchner Zeitung, has issued a denial, stating that the Government has no official knowledge of the arrest.

General Ludendorff has issued a statement today to the effect that the oath he gave when he was released on parole only binds him to refrain from any political activity against the existing Government of Bavaria. While this particular incident is under consideration. Beyond this he still considers himself free to work for and to support the program outlined by the Nationalist fighting organization at Nuremberg on Sept. 1, when Hitler was present.

There have been practically no further demonstrations in the town, and curfew hour has been extended until 10 o’clock. Tomorrow the theatres are to reopen.

NOVEMBER 20, 1923

By CYRIL BROWN

By Wireless to The New York Times.

BERLIN, Nov. 19—Food rioting and plundering have been resumed in Greater Berlin and the stores so far unplundered remain closed. If you succeed in slipping in by the back door it is only to find the shopkeepers unwilling to sell anything, particularly the butchers, who meet the world-be customer with the stereotyped answer. “We have no meat.” This shortage is largely due to the expectation that the price of meat as well as other food prices will be many hundred per cent higher in a day or two.

A prospective meat price for tomorrow of 7,000,000,000,000 marks per pound was quoted today, which at the best bootlegger rates for a dollar is nearly per pound. Bread was unbuyable either yesterday or today. It is learned that the military dictator, General von Seeckt, is considering some sort of food rationing system, the details of which are being worked out. These provide that the fashionable restaurants, semi-empty hotels, dance halls and other places known as “luxury enterprises” shall, when the necessity becomes acute, be converted into mass feeding stations and “warming rooms.”

AUGUST 5, 1932

By HALLETT ABEND

Wireless to The New York Times.

SHANGHAI, Friday, Aug. 5—The situation in Manchuria and North China grew more grave today as the Japanese concentrated more troops at Chinchow, whence they are in a position to strike either at Jehol Province or North China, and the renewed widespread attacks on South Manchurian cities by irregulars continued unabated.

The tension also increased greatly at Shanghai, where the Japanese naval patrol was more than doubled, the commander condemning the “terrorizing tactics” of boycott organizations.

Furthermore, expressions by both, Japanese and Chinese leaders showed determination to settle the Manchurian issue by the strongest measures. General Shigeru Honjo, the commander of the united Japanese armies in Manchuria, said that he had decided to resort to “last measures” because Gonshiro Ishimoto, the kidnapped Japanese head of an official mission in Jehol, was ill and there was little prospect of his rescue.

At the same time, the Nanking Government approved the agreements reached at the Peiping Politico-Military Conference, which were understood to call for a strong policy, and Governor Han Fu-chu of Shantung issued a statement from Tsinan expressing willingness to lead his own troops in an attempt to recover Manchuria—regardless of the prospects of success.

General Wu Pei-fu, the former North China war lord, also announced in Peiping that he favored a campaign against Manchukuo.

Military observers believe the increased activity of the Chinese irregulars between the South Manchuria Railway zone and the Gulf of Liaotung constitutes part of a carefully pre-arranged plan for a campaign to harass the Japanese and increase the prospects for success of a drive from Jehol against Mukden and Changchun, the capital of Manchu-kuo.

In Peiping the nervousness has mounted to new heights and the directors of the museum located in the Forbidden City rented a warehouse today in the legations quarters in order to be able to safeguard the palace treasures from possible looting. They appropriated $100,000 to pay for a rush order for packing cases in which to store the jewels and art treasures valued at tens of millions of dollars and appropriated an additional $30,000 to take out war risk insurance on the irreplaceable objects of art.

These steps were taken after the directors discarded a tentative plan for surrounding the museum with machine guns, electrically charged barbed wire and a trench system.

The Japanese commander of the patrol forces in Shanghai, in announcing his decision to increase the number of the patrol units from eight to twenty-two, assured the Japanese residents of the city of the Japanese Government’s readiness to afford them adequate protection.

“The Japanese residents are hereby notified,” he said, “that if their business is interfered with or they are terrorized by anti-Japanese groups, to report to the landing party immediately. Protection of the interests of the Japanese here is my paramount duty. Our reviving trade has been damaged and the situation is becoming worse through illegal interference with the transportation of Japanese goods and the terrorizing tactics of the so-called Bloody Group for the Extermination of Traitors.

“Really, no words are too strong against the activities of the Chinese people,” he added.

AUGUST 8, 1932

By FREDERICK T. BIRCHALL

Special Cable to The New York Times

BERLIN, Aug. 7—The busiest of the Ministerial buildings that house the German Government these days is a solid structure of gray granite away from all the rest of the pleasant tree-lined streets where the Landwehr Canal cuts through the city’s heart.

It was formerly the War Department, but war is a word that has fallen into disfavor in present-day Germany. Besides, all the nations have signed the Kellogg Pact. So the building is now the Reichswehr-ministerium, the home of the German Ministry of Defense.

It used to swarm with heel-clicking, brilliantly uniformed officers smartly tailored to the last button, and on the whole it was not the most comfortable place for a civilian to visit. Nowadays, however, there is as much mufti as uniform among the occupants.

A white marble bust of the von Moltke who carried the German armies to Paris in 1870 and brought them back triumphant still stands in the entrance hall, and once daily a slim platoon of the Reichswehr, which furnishes the sentries on duty here, at the Presidential Palace and at a few other government buildings, marches in through the heavy arched gateway and passes out again.

But the atmosphere is generally quite different from the old days and just now the building’s principal distinction is that it covers the activities, military and political, of Generalleutnant Kurt von Schleicher, Minister of Defense in the von Papen Cabinet and the most talked of man in Germany.

Half of Berlin speaks of General von Schleicher with bated breath. He is the “iron man” dear to the German heart, the “man behind the Cabinet’’—he is actually in it—the “real ruler of Germany,” and so on.

General von Schleicher himself speaks little, but when he does he usually has something to say, as France discovered quite recently when for the first time in his life he talked over the radio.

So his fame has grown. When the Communists become quiescent it is because they fear von Schleicher; when the Nazis milden their truculence it is because the General has given a quiet tip to Adolf Hitler that things have gone far enough.

Nobody ever credits the rather kindly von Papen with any of these things. It is von Schleicher who has temporarily taken the place in German legend that the former Kaiser and President von Hindenburg have held in turn.

I sought out General von Schleicher in his office to ask him to elaborate somewhat on the views that he recently expressed regarding Germany’s present handicap among the nations and her determination immediately to set about making her future worth while.

It was an ordinary office such as might have been occupied by any German business man. The only uniforms visible were those of the unteroffizier orderly at the building’s portal who took in my name and the General’s Adjutant, who listened to the interview.

The man who rose at his desk in greeting was clad in a gray business suit, and I should say that shrewdness rather than sternness was the prevailing characteristic of his rather genial face. They say that no man knows better and estimates more correctly the political currents in Germany. Probably he could bang the desk to good effect, but certainly he did not look half as truculent as our own General Dawes.

General von Schleicher, it had previously developed, had become gunshy regarding interviewers after several rather disastrous experiences. He had therefore requested that the questions put to him be previously submitted in writing. He does not speak English, although a rather understanding twinkle in his eye seemed to indicate that he comprehended at least the drift of what was said in that language. His answers are here translated from the German.

“How does the Minister of Defense view the internal state of Germany?” was the first question.

“I can answer the question only so far as it concerns my official capacity as Reichswehr Minister” was the General’s cautious reply. “I object to the Reich-swehr being thrown into the struggle of internal politics. That I reject any sort of military dictatorship I made clear in my recent radio talk.

“The commander in chief of the Reichswehr is the Reichspresident. The Reichswehr is a non-political instrument of force which on given occasions the President has used to enforce his orders. The Reichs president is elected by the people. He alone in the scheme of German Government can claim the authority of a clear popular majority. The Reichs-wehr’s service to the people can therefore be no better performed than by obeying the President’ s orders.

“For a few days in July it was necessary to confer executive power on the commandant of the Berlin military district. By this means the President’s will was enforced without the Reichswehr having to intervene with its arms. I am convinced it will be so also in the future.

“The Reichstag elections show no difficulties in the government of Germany nowadays. The greatest success was attained by the radical parties, not only by the National Socialists but also on the other wing by the Communists. The outside world has ground for wondering at that. More than 60,000,000,000 marks (about $14,280,000,000) of our national wealth has been taken from us. Can anyone then really expect the German people to be content with existing conditions?

“On the contrary, there is reason for wondering that the German people bear their terrible distress so calmly and with such discipline.

“Neither must there be astonishment abroad at the rise everywhere in Germany of party organizations that violently battle against each other. This has been made possible not only by the fact that the authority of our sovereign State was undermined by the Treaty of Versailles. A country treated for thirteen years as a pariah by the outside world, a country to whom equality is denied to this very day, simply had to forfeit the respect of its own people.

“Only when the German Government can demonstrate to its people that it possesses equal rights with any other country in the world—only then shall we again have fully stable conditions in Germany, only then shall we be able to subject the parties and their organizations unquestionably to the State “There is therefore no question of German policy more important both with respect to domestic affairs and foreign relations than that of equality of rights. The German Government is determined to solve this question in the very near future.

“This leads to the second question you have asked me to answer—concerning my attitude on foreign policy.” (General von Schleicher had been asked to voice his views on the foreign situation, especially on the course of the disarmament conference and its results thus far.) “To me, as the Minister of Defense, the question of disarmament is in the very centre of foreign policy.

“Consider our position. By the treaties of 1919 we have the right to have the other signatories disarm according to the same methods that govern our own disarming. As a member of the League of Nations we have, moreover, the right to a degree of security equal to that of any other country.

“Thirteen years have passed since 1919 and our right is still unrealized. The disarmament conference sat for six months and adopted a resolution that neither achieves disarmament nor acknowledges equality of rights. What has become of all the nine principles formulated by all the governments at the beginning of the conference? They have found their graves in the debates in the technical committees.

“About President Hoover’s proposals, calculated to carry disarmament a long way forward, there was amiable talk, but none of their more important provisions was included in the final resolutions. Germany’s own self-explanatory demand for equal rights received no consideration, even though any disarmament convention can be worth something only when signed voluntarily by partners having equal rights. Germany therefore rejected the resolution.

“The German people have waited thirteen years for their due. They can wait no longer. Germany will not again send its representatives to Geneva unless the question of equal rights has been previously solved in conformity with the German position.

“On this question there are among us no party differences. No German Government could sign a disarmament convention that in all things does not accord Germany the same rights as any other country.

“If submarines, bombing planes, heavy artillery and tanks are now designated as a means of defense, by what justification can one deny Germany this protection?

“That Germany alone among the great powers is unable to provide for her national security constitutes an immoral condition that we can no longer tolerate. Either the disarmament provision of the Treaty of Versailles must be applied to all the powers or the right to rebuild her system of defense and make it equal to the needs of national security must be conceded to Germany.

“We want no armament competition. For financial reasons alone we are unusual in that respect. But just because of our distressed financial position we ought not to be spending money on the costliest and at the same time the least productive system of defense, forced on us by the Treaty of Versailles, but should spend every penny to the best advantage.

“We are dreaming neither of establishing a peace-time army of 600,000 men—such as France now maintains—or of competing with the great naval powers. We do not wish to threaten the security of our neighbors. We support every measure of disarmament. But we do demand for ourselves also security, equal rights and freedom.”

AUGUST 16, 1932

Professor Frederick J. E. Woodbridge, Theodore Roosevelt Professor of American History at the University of Berlin for the last year, returned on the Holland-American liner Volendam yesterday and said the probability of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists gaining power in Germany was not strong. He said he did not think it possible for Hitler to seize power and that the Nazis would have to wait for a majority in the Reichstag.

“All coalitions are very doubtful,” Professor Woodbridge said. “The present government, which does not depend on a coalition, is in a strong position and can keep up indefinitely because vast numbers of people do not want a disturbance.

“The present government is giving a sense of authority, control and progress. Hitler has undoubtedly proved a success as a leader of his movement. About his executive ability nobody as yet knows anything.

“I left Germany with the conviction that the German people, in spite of intense party differences and sentiments, would come through their present political difficulties with a genuinely constructive program and without civil war. When one looks at the political situation from the point of view of the strife of parties and partisan propaganda, one seems to see only chaos, disorder and peril; but as one observes what actually goes on from day to day and as one talks with people of different parties, one gets a profound sense of steadying forces that are firmly holding excesses in restraint.”

JANUARY 31, 1933

Adolf Hitler’s acceptance of the German Chancellorship in a coalition with conservatives and nonpartisans marks a radical departure from his former demand that he be made “the Mussolini of Germany” as a condition to his assumption of government responsibility. It represents at the same time a recession from their former position by President Hindenburg and the Conservatives, who hitherto had been set against entrusting the Chancellorship to Hitler although willing to permit him to participate in the government. The net result is not altered thereby.

For the first time in his spectacular and tempestuous career Hitler is now called upon to prove in deed what he has been promising in word to the many millions of his supporters. He takes office at a time when his own party is passing through a severe internal crisis, expressed in a bitter factional struggle between extremists who have insisted on extra-constitutional action and the more moderate elements who have maintained that the party could not continue in the Opposition forever and could survive only through constructive participation in the government.

This factional struggle, in which the Nazi leader had tried to placate both sides, assumed acute form last December with the resignation of the leaders of the more moderate faction, Gregor Strasser and Gottfried Feder. Strasser was Hitler’s chief executive. Feder was the party ideologist credited as being the real founder of the party.

Both resigned in protest against their chief’s refusal to participate in the government unless the powers of a dictator were given to him. This position, critics in the Nationalist Socialist party argued, was responsible for the loss of about 2,000,000 votes in the Reichstag elections last November.

Adolf Hitler (right) rides with German President Paul von Hindenburg after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany in January 1933.

Ever since Hitler first refused the Chancellorship in a Coalition Cabinet in August, 1932, there has been a constant dribbling away from his party.

The elections in Thuringia, which followed the losses suffered by the party in the last Reichstag elections, served to emphasize this point.

A powerful group of industrialists in the Federation of German Industries recently gave indications of a sharp change of attitude toward the National Socialists because of their radical trend. This group in the Federation of German Industries has been inclined in recent months to withdraw its support from the party and return to a policy of understanding with the German trade unions.

At the same time, however, a group of Nazi industrialists in the Rhineland and the Ruhr, who have been among Hitler’s chief financial backers, have urged him to drop his uncompromising attitude and join the government. According to recent dispatches from Berlin, former Chancellor von Papen was the “friendly broker” between the National Socialists and this group of industrialists.

Recent Berlin dispatches indicate also a deal between Papen and Hitler for the overthrow of General von Schleicher, who roused the displeasure of the Rhineland-Ruhr industrialists by his inclination to deal leniently with labor and to seek the support of the trade unions. In this policy, these industrialists foresaw the abandonment of the economic program laid down by Papen as Schleicher’s predecessor in the Chancellorship.

Outstanding is the dramatic element of Hitler’s accession to power at the age of 43. The new Chancellor began as the son of poor parents in Austria. For a long time he was not even a German citizen, but a man without a country. His political career began in a very un-promising manner in 1921.

The Nazi leader went to Germany in 1914 at the outbreak of the war and enlisted in the German Army. By this act he sacrificed his Austrian citizenship. He had a good war record, being gassed, wounded and winning a silver war service medal.

The advent of the German Revolution with the military collapse of Germany in 1918 found him a bitter opponent of the revolutionary upheaval. He hated the republic from the day it was horn and vowed that he would never rest until he had brought about a counterrevolution against the men and the parties whom he considered responsible for the downfall of the empire.

With General Erich von Ludendorff, who was one of his early supporters but with whom he parted company in later years, he attempted a revolution in Munich, which was easily suppressed by the Bavarian Government on Nov. 8, 1923.

The uprising was to have been the signal for a general monarchist revolution. The collapse of the movement led to the sentencing of Hitler to five years in prison. He was liberated after serving a year in a Bavarian fortress.

He resumed activities on a large scale in 1928. From that time his movement, stimulated by the economic depression, progressed fast. By 1930 the National Socialist party had won 107 seats in the Reichstag. In July, 1931, this number was increased to 230.

Hitler received his first official political recognition in 1932 when Chancellor Heinrich Bruening consulted him on a proposal to extend the term of President von Hindenburg by act of Parliament to avoid the disturbance of a Presidential contest. The Nazi flatly refused. He became a candidate against von Hindenburg but was defeated by more than 6,000,000 votes.

In that election Hitler reached the peak of his strength, polling more than 13,000,000 votes. The reversal of the tide came with the Reichstag elections a few months later, when the National Socialists suffered a loss of about 2,000,000 votes.

MARCH 2, 1933

Wireless to The New York Times.

PARIS, March 1.—With growing anxiety the French are watching events across the Rhine and Chancellor Hitler’s repressive measures, in which they see a determined intention to achieve a Fascist dictatorship.

France, judging by today’s press, even seems distinctly inclined to blame the Nazis themselves for the fire that wrecked the Reichstag Building, and sees in it simply a crude excuse on Herr Hitler’s part to crush the Opposition just before the elections.

Leon Blum, the Socialist leader, is particularly outspoken. He calls the fire “a gross, cynical camouflage that could not fool the public in any other country but Germany,”

The semi-official Temps likewise throws considerable doubt on the authenticity of the charges against the Communists concerning the fire. It points out certain weaknesses in the story, as well as the Nazi’s interest in making the most of it. The paper particularly expresses worry over the similarities that it sees between Herr Hitler’s actions now and those of Premier Mussolini of Italy in 1922, and states that the German Chancellor has the same policies, ideas and methods.

“All that can be clearly said is that the German crisis, which has been developing for months, is now degenerating into civil war and pushing a great nation more and more toward anarchy and political chaos,” the Temps concludes. “No one in history has yet been able to succeed in achieving a durable State and order by means of disorder.”

MARCH 3, 1933

Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, March 2.—The plight of Jews in Germany was emphasized tonight by Dr. Chaim Weizmann, presiding at a dinner to the “friends of Palestine in the British Parliament” given by the British section of the Jewish Agency.

No unbiased observer with any respect for justice and fair play, Dr. Weizmann declared, could remain indifferent to the situation in Germany, where the “economic and political existence of all Jews is imperiled by the policy which had inscribed anti-Semitism in its most primitive form as an essential part of its program.”

It has been only a few days, he added, since Captain Hermann Wilhelm Goering, Minister without portfolio, accused the Jews of “organizing the cultural disruption of Germany” and it was a severe shock to civilized people to discover that it was possible for a great people like the Germans to relapse into barbarism in its attitude toward a small, law-abiding minority of its citizens.

“To our people in Germany, whose position, by all accounts, is becoming daily more intolerable,” declared Dr. Weizmann, “we can only counsel courage and endurance. I feel our sympathy is shared by all friends of progress, worldwide. In the hour of their trial it is well that our fellow-Jews in Germany should know they do not stand alone but that the full weight of enlightened opinion in all civilized countries, especially in England, is behind them in their struggle against the forces of reaction.”

There were 500 guests at the dinner, including 100 members of Parliament.

MARCH 6, 1933

Wireless to The New York Times.

PARIS, March 5—Frenchmen eagerly snatched the special editions of the Paris dailies from the hands of shouting news vendors late tonight, then in most cases threw down the papers with expressions of disgust. It was obvious they expected or at least hoped for a popular electoral reaction against the Hitler dictatorship in Germany.

A few hundred Communists began a march down the grand boulevards, singing the “Internationale.” When they reached the offices of Le Matin police reinforcements were waiting for them and broke up the demonstration. The crowd reading newspaper bulletins was left unmolested. Reflecting the attitude of many Frenchmen, Leon Blum, the Socialist leader, declared in a speech tonight:

“The Fascist activities of the Hitlerites hold for France no immediate danger of war. These activities will logically be directed toward the rearmament of Germany, which will constitute for her a symbol of revival and liberation. The danger then will lie with the counter-measures of the neighboring States, which are capable of dragging all of us into an armament race, and we know where that will lead.

“We must forbid the rearmament of Germany and push to a successful conclusion the work of the Disarmament Conference. But I fear first war, then ensuing misery, will be required to reforge the unity of the workers.”

MARCH 28, 1933

By HUGH BYAS

Wireless to The New York Times.

TOKYO, March 27—Count Ya-suya Uchida, the Foreign Minister, notified the League of Nations today of Japan’s decision to withdraw because of “irreconcilable” differences with the League over Manchuria.

But in announcing the decision to the nation the government, through the lips of Emperor Hirohito and the Premier, Admiral Viscount Ma-koto Saito, repudiated the “Back to Asia” policy and solemnly assured the people that Japan did not seek to isolate herself in the Far East and would continue to cultivate the friendship of Western powers and to cooperate with them.

The note addressed to the League tersely repeated the contention so often heard at Geneva that, as China was not an organized State, the instruments governing the relations between ordinary countries must be modified in application to her.

The report adopted by the Assembly on Feb. 24, it is declared, besides misapprehending Japan’s aims, contained gross errors of fact and the false deduction that the Japanese seizure of Mukden in September, 1931, was not defensive. Failure to take into account the tension which preceded and the aggravations which followed the seizure was alleged.

While this was being cabled to Geneva an imperial rescript was promulgated informing the nation that Japan’s attitude toward enterprises intended to promote international peace had not changed. The official translation continues:

By quitting the League and embarking on a course of its own, our empire does not mean that it will stand aloof in the Far East nor isolate itself from the fraternity of nations.”

The same note is struck in Premier Saito’s message to the nation. As it is Japan’s traditional policy, he says, to contribute to the promotion of international peace, the government will continue to cooperate in international enterprises designed to further the welfare of mankind.

“Nor does this country propose to shut itself up in the Far East, but will endeavor to strengthen the ties of friendship with other powers,” he adds.

This double repudiation of the “Back to Asia” doctrine probably is correctly interpreted as a result, of views expressed by the Privy Council. Many of the wisest statesmen regret the course which has left Japan alone. Believing, however, in the essential justice of her cause they could but acquiesce in secession.

Lieut. Gen. Sadao Arakl, the War Minister, issued a statement declaring the nation had been reborn in moral principles. The empire’s positive policy had been definitely established, giving an opportunity for national expansion.

BERLIN, March 29 (AP)—Professor Albert Einstein has taken steps to renounce his Prussian citizenship.

Professor Einstein, who is a Jew, became a citizen in 1914 when he accepted a position with the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Upon landing at Brussels after his recent trip to the United States, he wrote to the German Consulate there for information about the steps necessary to end his citizenship. He pointed out that he formerly was Swiss.

Professsor Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany, but subsequently his family moved to Switzerland and he became a Swiss citizen.

Before sailing recently for Europe the professor said:

“I do not intend to put my foot on German soil again as long as conditions in Germany are as they are.”

OCTOBER 2, 1935

Wireless to The New York Times.

BERLIN, Oct. 1—The regulations governing the enforcement of the so-called Nuremberg laws adopted by the National Socialist Reichstag Sept. 15 are still being worked out at the Ministry of the Interior, and no date has been set for their promulgation.

Fundamentally these laws are in force, however, and an official communiqué today sought to correct the prevalent impression that all mixed marriages, that is, marriages between “Aryans” and Jews would be decreed void. The new statute, it was stated, outlaws only such unions as have been consummated since last Sept. 17.

Meanwhile Jewry is anxiously awaiting the final implications of the laws, which were announced only in skeleton form in Nuremberg, and it is especially with reference to their effect on Jewish economic life that definitive clarification is awaited.

The draft decree adopted by the Reichstag confined itself to the purely racial and political aspects of the situation and omitted all reference to the limits that would be allowed Jews for business and economic activities.

Subsequent warnings from authoritative quarters against individual anti-Jewish boycott activities have stimulated a modest measure of hope in Jewish circles of a possible moderation of the hitherto silently condoned policy of economic persecution, which is being waged with almost unrelenting fury against the Jews in rural sections although it has not yet invaded the big cities in virulent form.

Meanwhile the Jews throughout Germany are passing through a transitional period that cannot fail to fill them with the deepest apprehension, and until their economic fate has been decreed in finality they will be compelled to defer all consideration of plans calculated to meet any fresh emergency.

The Ministry of the Interior today reminded all Germans of the flag law adopted in Nuremberg, which makes the swastika banner the sole authorized flag of the Reich. Not only will it now be flown exclusively from official flagstaffs but citizens are admonished to discard their old black-white-red colors and the various flags of the now obsolete States and provinces.

If a nationalist diehard in a fit of nostalgia cannot resist showing the old imperial flag his lapse will be condoned, but the Ministry expresses the hope that the populace will make its choice of flags unanimous.

As the new flag law forbids Jews to exhibit the Nazi banner, the Ministry reminds them that they are not allowed by law to compromise by displaying the black-white-red emblem on official occasions but are restricted in their choice to the Zionist colors.

Discussing the national implications of the Nuremberg laws in the German Jurists’ Gazette, Professor Carl Schmitt, well-known juridical authority, asserts that these statutes after a lapse of centuries again constitute a “German constitutional freedom.”

“For the first time our conception of constitutional principles is again German and today the German people once more are a German nation with respect to their Constitution, and statutory law,” says Professor Schmitt.

German blood and German honor, he adds, have become the basic principles of German law, while the State has become an expression of racial strength and unity. “Another momentous constitutional decision was proclaimed at Nuremberg when the Fuehrer announced that if the present solution of the Jewish problem fails to achieve its purpose re-examination of the situation will come up for consideration and the solution of the Jewish problem will then be left to the party’s judgment,” he continues. “That statement must be accepted as a grave warning, for it makes the party not alone the guarantee of our racial sanctuary but also the defender of our Constitution.”

By TURNER CATLEDGE.

WASHINGTON, Oct. 12—Events revolving around the Italo-Ethiopian unpleasantness, as they occurred during the last week on this side of the water, left a clear indication with official Washington of the possible difficulties ahead in our attempt to wear the tailor-made mantle of neutrality which a tired Congress cut out, altered slightly and pieced together in the closing hours of the last session.

One week ago tonight, Oct. 5, acting upon a direct mandate of Congress, President Roosevelt issued an embargo against American exportation of weapons and ammunition to both Italy and Ethiopia. He was following the very letter of Section 1 of Senate Joint Resolution 173. At the same time, in connection with the same proclamation, he put the American business public on notice that any trade with the belligerent nations would be at the risk of the traders. In this he went beyond the Congressional mandate, but was still within the clear intent of the authors of the resolution.

The next day, Sunday, Oct. 6, the President, by proclamation wirelessed from the cruiser Houston in the Pacific, issued a warning to all United States citizens against traveling on Italian or Ethiopian ships except at their own risk. Here he was using the discretionary authority granted by Section 6 of the resolution.

The following day, Monday, the first business day after our new and fixed neutrality policy became effective, a protest was raised by the Conference on Port Development of the City of New York. In a cable sent directly to the President at Cocos Island the conference branded his action as “ill-advised” and a “serious blow” to the commerce of the port of New York.

On Tuesday the members of the Export Managers Club of New York rose over their coffee cups at a luncheon at the Pennsylvania Hotel to declare their intention of trading with belligerent Italy and possibly with besieged Ethiopia, regardless of the President’s proclamation.

The next day Secretary of Commerce Roper, noted for his readiness to reassure business and industry in their dealings with the unpredictable administration in Washington, sought to assure American exporters that the government had no real objections to their trading with the warring countries. In effect, he told the exporters that the President had his fingers crossed when he issued the warnings as to trade and travel except as to trade in arms, for, as a practical matter, there could be no physical risks in trading with Italy, the only one of the two with any commercial attractiveness.

On Thursday Secretary of State Hull took occasion to re-emphasize the warnings to American traders against engaging in transactions of any character with either Italy or Ethiopia. He pointed to the greater purposes of the administration.

“I repeat that our objective is to keep this country out of war,” he said.

His statement and the deliberation with which he issued it were interpreted as a practical rebuke to Secretary Roper, as well as a redeclaration to the American people that the administration intends to follow the spirit as well as the letter of the neutrality resolution—at least for the present.

While these developments show the troubles which responsible officials already have encountered in following a non-discretionary method in keeping this country out of international involvements, they were much more significant from the standpoint of what they indicated for the future.

For the present, then, it can be safely predicted that the President will follow the course laid down or indicated by the neutrality resolution, regardless of the protests of exporters or shipping interests.

The phrase “for the present” is used advisedly. The test of this fixed method of keeping us out of war has not come. So long as the present conflict is confined to Italy and Ethiopia it may never come.

To date neither Mr. Roosevelt nor anyone else has had any definite indication that the neutrality resolution was not a generally popular act. It represented the sincere desire of the American people to stay out of the next war and the methods it prescribed were popular, so far as they were understood.

Officials in Washington wonder, however, if that popular mind might not be changed under stress as it was changed in 1916–17. They wonder what would happen, for instance, if other and more powerful nations should become involved and soon thereafter some of our commerce should be stopped on the high seas or some of our nationals should be killed.

These officials answer their own questions with the frank intimation that the United States is following a day-today policy under the neutrality resolution, but with every apprehension that this will not suffice in a real test. They pray that the test may not come before Congress reconvenes, when, with a more enlightened public sentiment to support its action, it might give the Executive a better device for keeping us out of war.

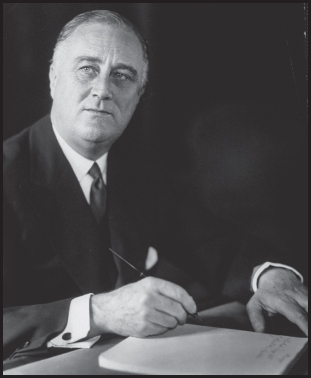

President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Oval Office, 1935.

So long as he follows his present course and throws himself completely on the law, the President can make short answer to those who would enlist this country in international action.

Importunings are heard on every hand for America’s assistance in stifling the present outbreak. Former Secretary of State Stimson joined in the chorus during the week. In a letter to the editor of The New York Times, published on Friday, Mr. Stimson pointed out that the President, by affirming that war existed between Italy and Ethiopia, had inferentially called attention to the fact that these nations had broken the Kellogg-Briand pact.

That agreement, Mr. Stimson insisted, was a promise by Italy and Ethiopia to the United States and other signatories that they would not resort to war for the solution of international controversies. The League, he said, had fixed the blame, and so it was within the province of the United States to act.

Mr. Stimson insisted that “all the elements for moral leadership in this crisis lie in the hands of the President.” But the President has been bound, or for self-protection has bound himself, with a law—Senate Joint Resolution 173.

By ANNE O’HARE McCORMICK

Wireless to The New York Times.

ROME, Oct. 12—For the capital of a country at war against Ethiopia and against the world, Rome is strangely apathetic. Premier Benito Mussolini’s new Italy is very old, after all, and it never seemed older than in these high-tension hours.

Behind the Fascist front is an older nation, careworn and warworn and with a long perspective. This Italy watches current events with a blasé somberness. The Romans, especially, have the attitude of stoical spectators at a drama of fate. Eager New York crowds may gather in Times Square to read bulletins from the war zone, but no such crowds gather in Rome. An Englishman arriving several days ago was amazed to find the atmosphere here less tense than in London. Outsiders cannot imagine how completely Italy is shut in with her own thoughts. She is shut in with history, too. World opinion is filtered and colored before reaching the people. What does strike home is that they have seen so many things pass that all, from Mussolini to the oldest cabman, believe that the cloud of opprobrium will dissolve quickly, just as world sentiment softened toward Japan, Germany and other lawbreakers.

How much does Italy care for the moral and material reprobation of other nations? Judging by outward signs, not much. How much do the people know? The masses, reading only the Italian press, have little idea of the extent of the condemnation over the invasion of Ethiopia. External reactions are employed here as an instrument of internal policy. Thus the most virulent anti-Fascist attacks from abroad are headlined or suppressed as national feeling needs to be stirred up or toned down, while what opinion there is supporting the Italian stand is, of course, always featured. Quotations published in the past few days—from J. L. Garvin of The Observer, London; Frank Simonds, In the Nation, New York, and selected excerpts from editorials and letters in the French, British, American and German press—might easily convince the reader that the great body of foreign sentiment recognizes the justice of the Italian case.

Educated Italians know what the world thinks. Virtually all read French and Swiss newspapers circulating in every city by the thousands. Mussolini knows; a member of his clipping bureau reports Il Duce insists these days on seeing only the unfavorable criticism, particularly from the English-language press. He cares enormously about foreign opinion. That his delegate submitted to the humiliation of sitting at Geneva to be condemned proves how much Mussolini desires to remain in the League, not only to fulfill the pledge made to France a month ago, but also to maintain his influence in Europe. Italy wants to be quartered but not quarantined in Africa.

The implication of events does not escape even the cabman. The League vote, though expected, had a depressing effect. So had President Roosevelt’s action anticipating Geneva in declaring a state of war and imposing the first official penalties. The League phalanx, however unreliable it may be in action, casts a rather black shadow over this peninsula. The American move was officially played down here as a measure assuring neutrality, but the people instinctively recognize in the President’s swift asperity a judgment on Italy and a reinforcement of the British determination to make sanctions work.

The Italians know more than to care about world indignation, but the weight of the censure presses, and to one on the move they are an abnormally sensitive people. The mobilization against them, instead of dividing the nation and wrecking the regime responsible, has solidified Fascists and non-Fascists into 100 per cent Italians. Former Premier Vittorio Orlando, Italian member of the “big four” at the peace conference, is one of the many politicians of democratic Italy issuing from retirement their offers of services in a time of national emergency to the man who destroyed them.

To understand this it must be remembered that few among the vocal masses feel any sense of guilt at the aggression in Ethiopia. Questioning hundreds of persons in recent weeks the writer met only three—a young intellectual, an old liberal and a woman artist—suffering moral scruples over the breaking of pledges and the war.

Many quite honestly sympathize with “those poor Ethiopians,” bombed and invaded, but only because they had been left so long to fall ill and starve under brutal masters!

The Italians feel misgivings, fear and deep pessimism as to the future, but they are not conscience-stricken. In their own eyes it is they who suffer an injustice. Admitting freely they fight for “vital national interests” because they are convinced war is the only way out, they refuse to believe any other nation blocks their way for reasons more moral than opposing interests. In this Mediterranean of misunderstandings, British battleships frighten Italy, and Italian submarines exasperate the British by popping up to salute, it is said, in the most unexpected places. Neither side can see the other’s point. It is difficult, because the outlooks inside and outside Italy are as different as views through a window pane and a mirror.

The night after the news of Adowa troops in action were shown marching across a movie screen the audience neither applauded nor cheered. As it watched in silence the mind of one spectator traveled back to a Berlin theatre after conscription was proclaimed last March. The German audience went into a delirium at the sight of goose-stepping Reichswehr units. But the Italian mood is unlike the German. Between the Italians’ organized mass meetings, with their flares of joy or anger, the everyday pitch is one of grim resignation. It is a new note, more formidable than the old. Too many are veterans who think this country lost the lasts war and are resolved to “finish the job.” Too many are peasants, like the Tuscan farmer with two sons at the front.

“I want the other two to go,” he said. “Rotting at home is worse than war.”

This Italy does not care whether she pleases the world or not. Like all rebels against the established order, she has little to lose and is fatalistically prepared to lose it. Sanctions are dangerous because they will not stop the smoldering resentment of the penalized. The sunny Italy of yesterday is of darker mien today. It would be a fatal mistake to interpret this explosion as merely Fascist, as the imperial lust of Mussolini. In reality, it is the newest phase of world revolution—a poor nation organized to bait the rich. It can be interrupted, but with or without Il Duce it will go on.

Wireless to The New York Times.

LONDON, July 14—The goal of a perfect gas mask for every man, woman and child in Britain came nearer realization today. An official announcement spread the tidings that after long experiments government scientists had evolved a respirator that would give all necessary protection during a gas attack. Production will begin immediately on a huge scale, less than two decades after the war that was to end war forever.

As the first step toward providing millions of masks free of charge, the Home Office today submitted a supplementary estimate of £887,000 in the House of Commons. Previous estimates for the army, navy and air force had reached the colossal total of £188,000,000 and there is every prospect that Britain’s defense expenditure will reach £200,000,000 during the present budget year.

The government does not intend to issue the new masks to the public, it was explained today, “unless this becomes necessary,” but every effort will be made to have them ready for any emergency. The masks will be stored in convenient centers throughout the country. Arrangements will be made for citizens to try them on. Authorities today expressed hope that the public would “take advantage of the opportunity.”

Today’s gas mask estimate included provision of £25,000 for purchasing and equipping two factories near Manchester, £7,000 for additional staff in the Air Raid Precautions Department of the Home Office, and £5.000 for a civilian anti-gas school at Falfield, Gloucestershire.

In addition, the Commons will be asked to appropriate £100,000 extra for the secret service, bringing the total for the year to £350,000, while the biggest item of all is an additional £2,930,000 needed for a cattle subsidy to British farmers.

Coincident with news of the antigas precautions there were more signs today of the deadly seriousness with which Britain is rearming. Alfred Duff Cooper, the Secretary for War. told the Commons that he had decided to appoint Vice Admiral Sir Harold Brown, the engineer-in-chief of the fleet, as Director General of Munitions Production, with a seat on the Army Council. The new official will be responsible to Mr. Cooper for coordinating and speeding the production of munitions.

The appointment is regarded as another step toward a Ministry of Munitions, which Winston Churchill and others with war-time experience have been demanding for a year or more.

Cyclists of the London police unit wearing gas masks and protective suits during an exercise, 1936.

JULY 19, 1936

By The Associated Press

MADRID, July 19—The Leftist Cabinet of Premier Santiago Casares Quiroga, harassed by a military revolt in Spanish Morocco and the Canary Islands and outbreaks in Spain itself, resigned early today. It took office last May 13.

By WILLIAM P. CARNEY

Wireless to The New York Times.

MADRID, July 18 (Passed by the Censor)—The Spanish Government announces that an extensive plot against the republic has broken out. It is now learned from the government that rebels seized the radio station in Ceuta, Spanish Morocco, and broadcast an announcement purporting to have been issued by the Seville radio station stating that all government buildings in Madrid had been seized.

The government also announces that the Morocco operations were connected with a similar plot in Spain.

The plot was quickly suppressed, according to the government by promptly arresting many army officers, including General Barrera, who entered the Guadalajara military prison this morning.

The government further states that the military aviation remained loyal to it and that bombing planes sent from Spain bombarded Ceuta and Melilla, also in Spanish Morocco.

[A rebel force of 20,000 held complete control over Spanish Morocco last night, refugees reaching Tangier said, according to an Associated Press dispatch.]

It was learned from official sources that General Queipo de Llano had illegally declared martial law in Seville and had attempted to start a rebellion, which was quickly smothered by loyal troops there.

[From French border points came reports of fighting in various Spanish cities, including Cadiz, Burgos and Barcelona, according to The Associated Press, and at Hendaye it was rumored that all the garrisons in Andalusia had risen.]

A telegram from the Civil Governor at Las Palmas, the Canary Islands, said that he and the commanding officer of the Civil Guards there were barricaded in the Governor’s palace, which was surrounded and besieged by rebel troops. The Socialist workers’ union at Las Palmas has declared a general strike to show its sympathy with the government.

Madrid presented a perfectly normal aspect today. It was officially denied that the rebels’ plan was gradually to close in on the capital and strike here last. The government said in an official statement broadcast repeatedly today from the Ministry of the Interior, “Public order has not been disturbed in Madrid or anywhere in the provinces.”

The government categorically repudiated rumors that troops had crossed the straits from Morocco and landed at Algeciras or that General Francisco Franco, military Governor of the Canary Islands, had joined the rebellion.

[Reports from North Africa said General Franco was heading the revolt in Morocco.]

Rumors of a military uprising in the Balearic Islands were also officially refuted.

It was officially announced that a “foreign airplane,” intended to bring the revolt’s leader to Madrid from Morocco had been seized.

A joint note issued by the Socialist and Communist labor organizations was broadcast by a union radio station in Madrid tonight. It said that the Marxist trade unions would declare general strikes wherever martial law has been declared by military governors without the government’s authorization.

All the higher army officers in Madrid called on the War Minister last night to assure him of their loyalty and readiness to fight for the defense of the republic.

A statement broadcast by the government early this morning said:

“Enemies of the State are still indulging in spreading false news, but the loyalty of all the forces in Spain to the government is general. Only in Morocco are there still parts of our army that are showing a hostile attitude toward the republic.

“The Ceuta radio station is trying to create alarm by broadcasting the announcement that some ships have been seized by rebel troops and are heading for the peninsula. The news is completely false.

“At the present moment our fleet is making for Spanish Morocco ports and is encountering no opposition in its efforts to restore peace. Peace and order will be completely restored very shortly.

“The government wishes to make known once more that the rumor in connection with the proposed declaration of martial law in Spain is absolutely baseless. There is no power in Spain other than the civil one and all other institutions in Spain are subordinate to the civil power, which is the one power in command.”