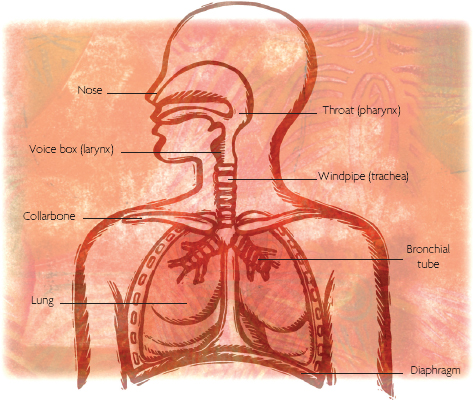

Your respiratory system stretches from your nose to your lungs, encompassing your nasal passages and sinus cavities, the back of your throat (pharynx), and your voice box (larynx), windpipe (trachea), bronchial tubes and lungs. It serves two life-giving purposes – bringing oxygen into your body and releasing waste matter – and enables a uniquely human quality, your ability to speak.

Each time you inhale, your respiratory system fulfils its first function, bringing atmospheric air into your lungs. The oxygen within this air is absorbed into your bloodstream and then transported to every cell in your body. Without this oxygen, your cells would die in a few minutes. The second task of your respiratory system is cleansing. Each time you exhale, you release gaseous waste matter from your body – mainly byproducts of metabolism. As you breathe out, air passes over your vocal cords, allowing you to express yourself through your own unique sound. In no other body system does the outside environment, with all its germs and pollution, have so much contact with your sterile inner regions.

The nose is the first part of your body to engage with breathing and it also plays an important protective role in your survival. As the seat of your olfactory mechanism – your most primitive sense, smell – it warns you of impending danger. Nature has also designed it as the ideal mechanism for filtering incoming air to protect the delicate lining of your lungs. Each nostril leads to an air passage separated by a bony structure made of cartilage called the septum. The internal portion of your nostrils is lined with microscopic hairs, known as cilia. When you breathe through your nose, these filters cleanse the air you inhale of dust, pollen, airborne germs and pollution. If you breathe through your mouth, without these filters, you may suffer a dry mouth, sore throat or catch a cold as a result. You should therefore only breathe through your mouth when a cold obstructs your nostrils, or when you need more air than your nostrils can comfortably inhale, such as when running.

Breathing through your nose also protects your respiratory system by humidifying the incoming air to keep the mucus membranes lining your nose, throat and respiratory passages moist. They then form a second line of defence, trapping dust and bacteria on their sticky surfaces. Mouthbreathing dries out the mucus membranes, making them less effective. Breathing through your nose also allows your nasal cavities and sinuses to bring the air you inhale to body temperature, as cold air irritates the respiratory system. Regular nose-breathing clears your sinuses, the internal cavities behind your cheekbones and forehead. You may only become aware of them when they are inflamed by a cold or hayfever, but clear sinuses promote good air circulation, bringing a feeling of lightness and freedom from headaches. They also add resonance to your voice.

After the air has entered your nasal passages, it moves down the back of your throat (pharynx) and past your larynx. This voice box contains your vocal cords and muscles that work together to produce sound. Air then descends into your trachea, or windpipe, which divides into two bronchial tubes.

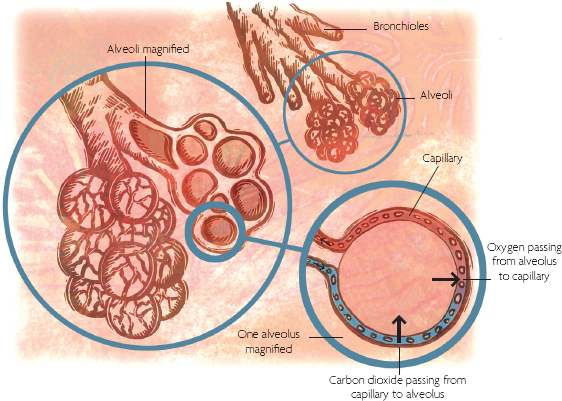

From here on, your respiratory system resembles two bunches of grapes – each bronchial tube sub-divides, becoming smaller until the passages consist of no more than a single layer of cells. Each passage ends in a tiny air sac, called an alveolus. Your lungs are composed of millions of these microscopic grape-like sacs. The membrane enclosing each one comprises a thin layer of cells surrounded by a network of capillaries (small blood vessels). Here the all-important “gaseous exchange” takes place (see below).

The floor of your chest cavity is formed by a domed muscle, which is known as the diaphragm. This muscle separates the chest cavity from your abdominal cavity. Your lungs and heart are enclosed by your ribcage, which is moved by the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles between your ribs. These muscles increase the volume in your ribcage, which lowers the pressure within the chest, causing you to inhale.

When your inhalation is complete, there is a short pause as the inbreath becomes the out-breath. A quiet, relaxed exhale is largely passive, resulting from the elastic recoil of your lung tissue and rib structure, which re-sets the diaphragm for your next breath. For active exhaling, some of your intercostal and abdominal muscles can be recruited.

The average adult at rest breathes 15–18 times per minute. With each inhalation, you draw approximately half a litre (1.75 pints) of air into your lungs. Every time you exhale, an equal amount of air is expelled. The air you inhale comprises about 79 percent nitrogen, 20 percent oxygen and 0.04 percent carbon dioxide, with traces of other gases and water vapour. The air you exhale contains the same amount of nitrogen, but the oxygen content falls to 16 percent and the carbon dioxide rises to 4 percent, so the most significant change between breathing in and out is the exchange of 4 percent oxygen for 4 percent carbon dioxide.

Oxygen from the air you inhale passes into your capillaries (small blood vessels) through the thin porous membranes of your alveoli, or tiny air sacs. Simultaneously, carbon dioxide from the blood moves into the air sacs to be breathed out. After your blood has been oxygenated in your lungs, it travels to your heart and is pumped around your body, delivering oxygen and nutrients to every cell, where it picks up the gaseous waste products of metabolism, including carbon dioxide, and takes them to your lungs, ready to be exhaled.